Abstract

This systematic review provides an overview of the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in reducing suicidal cognitions and behavior in the adult population. We identified 15 randomized controlled trials of CBT for adults (aged 18 years and older) that included suicide-related cognitions or behaviors as an outcome measure. The studies were identified from PsycINFO searches, reference lists, and a publicly available database of psychosocial interventions for suicidal behaviors. This review identified some evidence of the use of CBT in the reduction of both suicidal cognitions and behaviors. There was not enough evidence from clinical trials to suggest that CBT focusing on mental illness reduces suicidal cognitions and behaviors. On the other hand, CBT focusing on suicidal cognitions and behaviors was found to be effective. Given the current evidence, clinicians should be trained in CBT techniques focusing on suicidal cognitions and behaviors that are independent of the treatment of mental illness.

Keywords:

Introduction

Internationally, it is estimated that 800,000 people die by suicide each year. Suicide is the 15th leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for 1.4% of all deaths, and the second leading cause of death among 15–29 year olds globally.Citation1 In the period between 2000 and 2012, suicide rates dropped by 9% internationally.Citation1 This statistic masks considerable cross-national differences, but indicates a global trend toward a reduction in suicide. Suicide prevention strategies are therefore having some impact on the suicide rate. To date, there is good evidence to suggest that universal prevention strategies that target entire populations, such as the restriction of access to lethal means, are effective in reducing suicide rates.Citation2 Such strategies have become central to national responses to suicide prevention. To further reduce suicide deaths and improve patient outcomes, these universal strategies need to be supplemented with selective or indicated prevention strategies that target groups or individuals at high risk for suicide.

Such targeted interventions may focus on individuals seeking treatment for mental illness. Mental illness is one of the strongest risk factors for suicide, having been implicated in 91% of completed suicides.Citation3 The risk of suicide is highest among those with borderline personality disorder, followed by depression, bipolar disorder, opioid use, and schizophrenia.Citation4 It is estimated that between half- and three-quarters of all suicides would be avoided if mental illness were eradicated.Citation3 Similar population attributable risk estimates exist between smoking and lung cancer.Citation5 Recent reviews have shown that antipsychotics reduce the risk of suicide in people with schizophreniaCitation6 and that lithium is an effective treatment for reducing the risk of suicide in people with mood disorders, and bipolar disorder in particular.Citation7 Whether antidepressants reduce suicide risk is debatable,Citation8–Citation10 perhaps due to the frequent exclusion of actively suicidal participants from antidepressant trials.Citation11,Citation12 Psychotherapies, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), have not been shown to improve suicidal outcomes when mental illness is the main treatment focus.Citation13

On the other hand, both CBT and DBT have been shown to be effective in reducing suicidal risk when these treatments focus on suicidal cognitions and behaviors rather than mental illness.Citation13,Citation14 This suggests that better patient outcomes may arise when psychotherapy focuses on suicidal cognitions and behaviors as dysfunctional individual factors rather than symptoms of mental illness.Citation15 Alternatively, the discrepant findings regarding psychotherapies tailored toward either mental illness or suicidality may also be due to the lack of power and inadequately designed studies. Generally, randomized controlled trials of psychotherapies for mental illness do not systematically assess suicidal behaviors as an outcome measure,Citation2 resulting in a poor evidence base. A recent review of 1,344 studies focusing on psychotherapy for depression only found three studies that reported outcomes related to suicidal cognitions or behaviors.Citation16 Over recent years, the assessment of suicidal cognitions and behaviors in studies of psychotherapies has improved. A publicly available database focusing on psychosocial interventions in general for suicidal ideation, plans, and attemptsCitation17 recently identified 154 randomized controlled trials that assessed suicidal cognitions or behaviors as an outcome measure.

The current review

This review aims to provide an overview of the effectiveness of CBT, specifically in reducing suicidal activity in the adult population. CBT is an umbrella term for various treatments that focus on challenging cognitive biases (through cognitive restructuring) and behaviors (through graded exposure and relaxation training). Given the therapeutic focus of CBT, this review will focus on studies that report either suicidal cognitions (ie, suicidal ideation) or suicidal behaviors (ie, deliberate self-harm and suicidal attempts) as outcome measures. Suicidal cognitions and behaviors clearly exist along a continuum of severity, and only a minority of individuals will progress from suicidal ideation and self-harm through to suicide attempts.Citation18 Regardless of severity, these cognitions and behaviors confer a degree of suicide risk and constitute targets for treatment in their own right.Citation13

In order to reduce heterogeneity and provide a more focused discussion, this review will exclude other psychosocial interventions and therapies, such as DBT, which include additional therapeutic strategies and components that limit comparability to standard CBT. Again to reduce the heterogeneity of the included studies, the scope of the present review will be limited to adults only (ie, those aged 18 years and older). Several recent reviews have focused on therapeutic interventions for suicidal cognitions and behaviors in adolescents.Citation19–Citation24 These reviews provide an up-to-date overview of the literature and also serve to highlight the developmental, clinical, and social issues that limit comparisons between adolescent and adult populations when considering suicidal outcomes.

The studies included in this review were identified via the PsycINFO database, which was searched from 1980 to August 2015 using the following search terms adapted from a previous review conducted by Tarrier et alCitation13: “suicid* AND therapy AND cognitive OR behavio*ral”, “CBT AND sui-cid*”, “CBT AND self-harm OR self-injury”, “CBT AND suicidal behavio*r”, “suicide* AND intervention”, and “suicide* AND therapy”. Only randomized controlled trials that compared CBT with a control group were included. Studies needed to be reported in English in a peer-reviewed journal, and suicidal cognitions and/or behaviors needed to be included as an outcome measure. Studies that included composite measures that could not be disaggregated into outcomes reflecting either suicidal cognitions or suicidal behaviors were excluded. Case studies, reviews, clinical descriptions, and discussion articles were excluded, as were pilot and feasibility studies. A total of 3,176 articles were identified through PsycINFO, and the titles and abstracts of these articles were inspected. Reference lists of relevant reviews and key articles were also inspected, as was the publicly available database of 154 psychosocial interventions mentioned earlier.Citation17

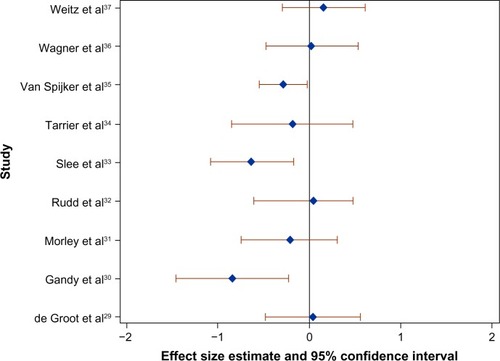

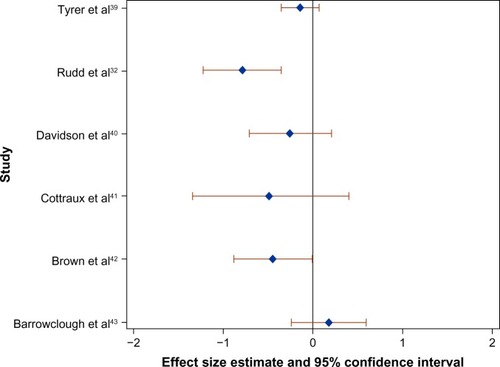

A total of 15 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. An overview of the findings from these studies is listed in and . All studies reported in and conducted the randomized controlled trials of CBT (including psychoeducation, applied relaxation, and graded exposure) for adults (aged 18 years and older) and included suicidal cognitions and/or behaviors as an outcome measure. Any suicidal outcomes reported during the active treatment phase were not included in and . In order to facilitate comparisons and synthesize the study findings, and also include an effect size estimate (in most cases, Cohen’s d) for each of the included studies. Several of these studies did not report effect sizes and related confidence intervals, and these were calculated instead from the available data using ClinTools Software.Citation25 For continuous variables, Cohen’s d and related confidence intervals were calculated using the posttreatment or follow-up assessment means and pooled standard deviations. In cases where odds ratios and proportions were provided rather than means and standard deviations, Cohen’s d was calculated using the standard formulae implemented in the ClinTools Software. In cases where the necessary data were not available in the original article, we contacted the corresponding author and requested the unpublished data. We were unable to source the data necessary for calculating effect sizes for one additional study,Citation26 which was subsequently excluded from this review. Negative effect sizes presented in and indicate an effect in favor of CBT. In the following discussion, these effect sizes are interpreted in relation to established criteria for trivial (<±0.20), small (≥±0.20), medium (≥±0.50), and large (≥±0.80) effect sizes.Citation27 Where data were available, forest plots depicting the study effect sizes and confidence intervals were also constructed using SAS Version 9.2.Citation28

Table 1 Overview of randomized controlled trials of CBT for adults (aged 18 years and older) that included suicide-related cognitions as an outcome measure

Table 2 Overview of randomized controlled trials of CBT for adults (aged 18 years and older) that included suicide-related behaviors as an outcome measure

Overview of findings

Ten of the 15 included studies measured suicidal cognitions,Citation29–Citation38 and there were a total of 17 comparisons with suicidal cognitions as the outcome of interest (). Seven of these comparisons focusing on cognitions elicited effect sizes that were trivial according to the established criteria. Four of these comparisons focusing on cognitions demonstrated small effect sizes in favor of CBT, and one study focusing on cognitions demonstrated a small effect size in favor of interpersonal therapy over CBT. Finally, when suicidal cognitions were the outcome of interest, there were four medium effect sizes and one large effect size in favor of CBT. The effect sizes for suicidal cognitions at the first assessment posttreatment are plotted in . Only studies with both an effect size and an associated confidence interval at posttreatment in are included in .

Figure 1 Forest plot of the effect size (Cohen’s d) of CBT on suicidal cognitions compared to the control group at the first assessment posttreatment in nine randomized controlled trials.

Abbreviation: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy.

Eight of the 15 included studies measured suicidal behaviors,Citation32,Citation33,Citation38–Citation43 and there were a total of 14 comparisons with suicidal behaviors as the outcome of interest (). Five of these comparisons focusing on behaviors demonstrated trivial effect sizes. Six studies focusing on behaviors elicited small effect sizes in favor of CBT, and one study focusing on behaviors elicited a small effect size in favor of usual care over CBT. Finally, when suicidal behaviors were the outcome of interest, there were three medium effect sizes in favor of CBT. The effect sizes for suicidal behaviors at the first assessment posttreatment are plotted in . Only studies with both an effect size and associated confidence interval at posttreatment in are included in .

Figure 2 Forest plot of the effect size (Cohen’s d) of CBT on suicidal behaviors compared to the control group at the first assessment posttreatment in six randomized controlled trials.

Abbreviation: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy.

Intervention focus

Seven of the 15 included studies focused on suicidal cognitions or behaviors as the main intervention focus.Citation32–Citation35,Citation38,Citation39,Citation42 Two studies focused on depression,Citation36,Citation37 and two studies focused on borderline personality disorder.Citation40,Citation41 The treatment focus of one study was psychosis with comorbid substance abuse,Citation43 while for another study the focus was substance use with comorbid suicide risk.Citation31 Two further studies focused on epilepsyCitation30 and grief in people bereaved by suicide.Citation29 The strongest effect sizes were elicited from interventions that focused specifically on suicidal behaviors or cognitions. The two treatments focusing on borderline personality disorder demonstrated consistent small effects in favor of CBT.Citation40,Citation41 For one treatment focusing on depression, CBT was not found to be more effective than an antidepressant or placebo pill. The same study demonstrated a small effect size in favor of interpersonal therapy for depression over CBT.Citation37 The other study focusing on depression found that suicidal outcomes did not differ between internet-delivered CBT and face-to-face CBT.Citation36

Control group

Three of the 15 studies included active control groups, while the remaining 12 studies used a usual care or wait-list control group. When focusing on CBT for borderline personality disorder, there was a small effect size in favor of CBT over Rogerian supportive therapy in the reduction of suicidal behaviors.Citation41 There were no differences between Internet-delivered CBT and face-to-face CBT for depression in reducing suicidal cognitions.Citation36 However, when examining change in suicidal cognitions within each group, the study authors only found a statistically significant change in the face-to-face CBT group from baseline to follow-up. One final study focusing on depression compared CBT with interpersonal therapy, imipramine, and placebo.Citation37 When focusing on suicidal cognitions, there was a small effect size in favor of interpersonal therapy over CBT, whereas the effect size differences between CBT, imipramine, and placebo were trivial.

Longer term follow-up

None of the studies measuring suicidal cognitions reported outcomes extending >9 months. Four studies focusing on suicidal cognitions included multiple assessment occasions. In one study, a trivial effect size persisted over 2-month and 6-month follow-up occasions,Citation34 whereas two studies demon strated diminishing effect sizes over subsequent assessment occasions.Citation30,Citation38 In one study, however, the superiority of CBT over usual care in terms of suicidal behaviors was only evident in later assessment occasions.Citation33 This same study also measured suicidal cognitions as an outcome and similarly elicited larger effect sizes in later assessment occasions. Otherwise, effect sizes either remained stableCitation40,Citation43 or diminishedCitation38 across assessment occasions when suicidal behaviors were the outcome of interest. One study focusing on suicide attempts demonstrated persistent small effect sizes at 1 year, 2 years, and 6 years posttreatment.Citation40 Another elicited a medium effect size at 2 years posttreatment.Citation32 Two other studies assessed deliberate self-harm at 2 years posttreatment. One study elicited a small effect size in favor of CBT,Citation41 whereas the other study elicited small effect size in favor of usual care.Citation43

Discussion

This systematic review identified 15 studies that focused on either suicidal cognitions or suicidal behaviors as outcomes for CBT. This review focused specifically on cognitions and behaviors because these are the central elements that CBT seeks to change. This review identified evidence for the use of CBT in the reduction of both suicidal cognitions and behaviors. CBT is therefore a useful strategy in the prevention of suicidal cognitions and suicidal behaviors.

CBT has been shown to be effective in reducing the symptoms of mental illnesses that are associated with an increased risk of suicide, including depression, anxiety, and psychosis.Citation44 Large clinical reports have also shown that suicidal cognitions and behaviors reduce significantly following CBT for depression.Citation45,Citation46 At present, however, there is not enough evidence from clinical trials to suggest that CBT focusing on these illnesses also reduces suicidal cognitions and behaviors. This is consistent with previous reviews of the literature.Citation13,Citation14 Mental illness is implicated in most suicides,Citation3 and the risk of suicide among individuals suffering from a mental illness is many times greater than that of the general population.Citation4 Given this evidence, the effective prevention and treatment of mental illness should be a central component of suicide prevention strategies. This review highlights the need to better evaluate the extent to which interventions such as CBT, which has been shown to be effective in treating a range of mental illnesses, also reduce suicidal cognitions and behaviors. Clinical trials may be constrained by ethical concerns over randomizing actively suicidal individuals to an inactive treatment arm. Following strict and comprehensive safety assessment and management procedures, such as those reported in the study by Brown et al,Citation42 should counteract these concerns. Innovative methods in the design of clinical trials, such as those informed by sequentialCitation47 or platformCitation48 methods, should also be adopted to optimize patient safety and reduce inactive treatment length.

Limitations

This review needs to be considered within the context of some limitations. A formal methodological quality evaluation was not undertaken for this review, but there are methodological problems observed in the primary studies that limit the conclusions of this review. For example, the sample sizes in the primary studies were occasionally small, and the representativeness of the study participants is often limited. We attempted to reduce the heterogeneity of the included studies, but the comparability across studies was ultimately low. This review covers treatments designed to address a variety of phenomena, and this is evident in the diversity of treatment components and associated clinical methods. Furthermore, inconsistencies in assessment measures and timing of assessment occasions limited the cross-study comparisons. Primary and secondary endpoints were uniquely defined for each study, making it difficult to combine the data and assess the short-, medium-, and long-term effectiveness of CBT on suicidality. It is also not clear whether the studies included in this review represent the full spectrum of severity with regards to suicidal cognitions and behaviors. Six of the studies in this review excluded participants with severe suicidal cognitions and/or behaviors,Citation30,Citation34–Citation38 and mean posttreatment scores on continuous measures of suicidal cognitions were often low even in inactive control groups. A restricted range of severity is likely to have some impact on the between-group effect sizes reported in this review, and may explain some of the small or trivial effect sizes generated. Finally, the suicidal outcomes assessed in these studies did not include completed suicide. The extent to which reducing suicidal cognitions and behaviors actually prevents completed suicide is unknown. It can only be assumed that reducing suicidal ideation, self-harm, and suicide attempts will have some, albeit unknown, effect on suicide rates.

This review focused on CBT, a psychotherapy known to be highly efficacious in the reduction of symptoms related to a range of mental illnesses.Citation44 CBT is a useful strategy for reducing suicidal cognitions and behaviors. In terms of CBT targeting mental illnesses, there is currently insufficient evidence to evaluate its effectiveness in reducing suicidal outcomes. Given the current evidence, clinicians should be trained in CBT techniques focusing on suicidal cognitions and behaviors that are independent of the treatment of mental illness.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health Organisation [webpage on the Internet]Preventing Suicide: A Global ImperativeKey Messages Available from: www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/key_messages.pdfAccessed October 23, 2015

- MannJJApterABertoloteJSuicide prevention strategies: a systematic reviewJAMA2005294162064207416249421

- CavanaghJTCarsonAJSharpeMLawrieSMPsychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic reviewPsychol Med2003330339540512701661

- ChesneyEGoodwinGMFazelSRisks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-reviewWorld Psychiatry201413215316024890068

- GoldneyRDDal GrandeEFisherLJWilsonDPopulation attributable risk of major depression for suicidal ideation in a random and representative community sampleJ Affect Disord200374326727212738045

- ReutforsJBahmanyarSJönssonEGMedication and suicide risk in schizophrenia: a nested case-control studySchizophr Res2013150241642024094723

- CiprianiAHawtonKStocktonSGeddesJRLithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysisBMJ2013346f364623814104

- KhanAKhanSKoltsRBrownWASuicide rates in clinical trials of SSRIs, other antidepressants, and placebo: analysis of FDA reportsAm J Psychiatry2003160479079212668373

- GunnellDSaperiaJAshbyDSelective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA’s safety reviewBMJ2005330748838515718537

- FergussonDDoucetteSGlassKCAssociation between suicide attempts and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: systematic review of randomised controlled trialsBMJ2005330748839615718539

- ZimmermanMChelminskiIPosternakMAGeneralizability of antidepressant efficacy trials: differences between depressed psychiatric outpatients who would or would not qualify for an efficacy trialAm J Psychiatry200516271370137215994721

- Van der LemRvan der WeeNvan VeenTZitmanFThe generalizability of antidepressant efficacy trials to routine psychiatric out-patient practicePsychol Med201141071353136321078225

- TarrierNTaylorKGoodingPCognitive-behavioral interventions to reduce suicide behavior a systematic review and meta-analysisBehav Modif20083217710818096973

- ComtoisKALinehanMMPsychosocial treatments of suicidal behaviors: a practice-friendly reviewJ Clin Psychol200662216117016342292

- LinehanMMSuicide intervention research: a field in desperate need of developmentSuicide Life Threat Behav200838548348519014300

- CuijpersPde BeursDPvan SpijkerBABerkingMAnderssonGKerkhofAJThe effects of psychotherapy for adult depression on suicidality and hopelessness: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Affect Disord2013144318319022832172

- ChristensenHCalearALVan SpijkerBPsychosocial interventions for suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts: a database of randomised controlled trialsBMC Psychiatry20141418624661473

- KesslerRCBorgesGWaltersEEPrevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity SurveyArch Gen Psychiatry199956761762610401507

- OugrinDTranahTStahlDMoranPAsarnowJRTherapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysisJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry201554297107.e225617250

- BrentDAMcMakinDLKennardBDGoldsteinTRMayesTLDouaihyABProtecting adolescents from self-harm: a critical review of intervention studiesJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry201352121260127124290459

- CorcoranJDattaloPCrowleyMBrownEGrindleLA systematic review of psychosocial interventions for suicidal adolescentsChild Youth Serv Rev2011331121122118

- KingCAMerchantCRSocial and interpersonal factors relating to adolescent suicidality: a review of the literatureArch Suicide Res200812318119618576200

- RobinsonJHetrickSEMartinCPreventing suicide in young people: systematic reviewAust N Z J Psychiatry201145132621174502

- RobinsonJCoxGMaloneAA systematic review of school-based interventions aimed at preventing, treating, and responding to suicide-related behavior in young peopleCrisis201334316418223195455

- DevillyGJClinTools Software for Windows: Version 4.0 (Computer Programme)Hawthorn, VICBrain Sciences Institute, Swinburne University2005

- BlumNSt JohnDPfohlBSystems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (STEPPS) for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial and 1-year follow-upAm J Psychiatry2008165446847818281407

- CohenJA power primerPsychol Bull1992112115519565683

- SAS Institute IncSAS version 9.2Cary, NCSAS Intsitute Inc2008

- de GrootMde KeijserJNeelemanJKerkhofANolenWBurgerHCognitive behaviour therapy to prevent complicated grief among relatives and spouses bereaved by suicide: cluster randomised controlled trialBMJ2007334760199417449505

- GandyMSharpeLNicholson PerryKCognitive behaviour therapy to improve mood in people with epilepsy: a randomised controlled trialCogn Behav Ther201443215316624635701

- MorleyKCSitharthanGHaberPSTuckerPSitharthanTThe efficacy of an opportunistic cognitive behavioral intervention package (OCB) on substance use and comorbid suicide risk: a multisite randomized controlled trialJ Consult Clin Psychol201482113014024364795

- RuddMBryanCJWertenbergerEGBrief cognitive-behavioral therapy effects on post-treatment suicide attempts in a military sample: results of a randomized clinical trial with 2-year follow-upAm J Psychiatry2015172544144925677353

- SleeNGarnefskiNvan der LeedenRArensmanESpinhovenPCognitive-behavioural intervention for self-harm: randomised controlled trialBr J Psychiatry2008192320221118310581

- TarrierNKellyJMaqsoodSThe cognitive behavioural prevention of suicide in psychosis: a clinical trialSchizophr Res20141562–320421024853059

- van SpijkerBAvan StratenAKerkhofAJEffectiveness of online self-help for suicidal thoughts: results of a randomised controlled trialPLoS One201492e9011824587233

- WagnerBHornABMaerckerAInternet-based versus face-to-face cognitive-behavioral intervention for depression: a randomized controlled non-inferiority trialJ Affect Disord2014152–15411312123886401

- WeitzEHollonSDKerkhofACuijpersPDo depression treatments reduce suicidal ideation? The effects of CBT, IPT, pharmacotherapy, and placebo on suicidalityJ Affect Disord20141679810324953481

- WeinbergIGundersonJGHennenJCutterCJJrManual assisted cognitive treatment for deliberate self-harm in borderline personality disorder patientsJ Pers Disord200620548249217032160

- TyrerPThompsonSSchmidtURandomized controlled trial of brief cognitive behaviour therapy versus treatment as usual in recurrent deliberate self-harm: the POPMACT studyPsychol Med200333696997612946081

- DavidsonKMTyrerPNorrieJPalmerSJTyrerHCognitive therapy v. usual treatment for borderline personality disorder: prospective 6-year follow-upBr J Psychiatry2010197645646221119151

- CottrauxJBoutitieFMillieryMCognitive therapy versus Rogerian supportive therapy in borderline personality disorderPsychother Psychosom200978530731619628959

- BrownGKHaveTTHenriquesGRXieSXHollanderJEBeckATCognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trialJAMA2005294556357016077050

- BarrowcloughCHaddockGWykesTIntegrated motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy for people with psychosis and comorbid substance misuse: randomised controlled trialBMJ2010341c632521106618

- ButlerACChapmanJEFormanEMBeckATThe empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analysesClin Psychol Rev2006261173116199119

- MewtonLAndrewsGCognitive behaviour therapy via the internet for depression: a useful strategy to reduce suicidal ideationJ Affect Disord2015170788425233243

- WattsSNewbyJMMewtonLAndrewsGA clinical audit of changes in suicide ideas with internet treatment for depressionBMJ Open201225e001558

- SchäferHMüllerHHConstruction of group sequential designs in clinical trials on the basis of detectable treatment differencesStat Med20042391413142415116350

- BerrySMConnorJTLewisRJThe platform trial: an efficient strategy for evaluating multiple treatmentsJAMA2015313161619162025799162

- GilliamFGBarryJJHermannBPMeadorKJVahleVKannerAMRapid detection of major depression in epilepsy: a multicentre studyLancet Neurol20065539940516632310

- BeckATSteerRARanieriWFScale for suicide ideation: psychometric properties of a self-report versionJ Clin Psychol19884444995053170753

- BryanCJRuddMDWertenbergerEEtienneNRay-SannerudBNMorrowCEPetersonALYoung-McCaughonSImproving the detection and prediction of suicidal behavior among military personnel by measuring suicidal beliefs: An evaluation of the Suicide Cognitions ScaleJ Affect Disord20141591522

- LinehanMMNielsenSLAssessment of suicide ideation and parasuicide: hopelessness and social desirabilityJ Consult Clin Psychol19814957737287996

- BeckATSteerRACarbinMGPsychometric properties of the beck depression inventory: twenty-five years of evaluationClin Psychol Rev19888177100