Abstract

Stress is experienced during cancer, and impairs the immune system’s ability to protect the body. Our aim was to investigate if isolation stress has an impact on the development of tumors in rats, and to measure the size and number of tumors and the levels of corticosterone. Breast cancer was induced in two groups of female rats (N=20) by administration of a single dose of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea 50 mg/kg. Rats in the control group (cancer induction condition) were allowed to remain together in a large cage, whereas in the second group, rats were also exposed to a stressful condition, that is, isolation (cancer induction and isolation condition, CIIC). The CIIC group displayed anxious behavior after 10 weeks of isolation. In the CIIC group, 16 tumors developed, compared with only eleven tumors in the control cancer induction condition group. In addition, compared with the control group, the volume of tumors in the CIIC group was greater, and more rats had more than one tumor and cells showed greater morphological damage. Levels of corticosterone were also significantly different between the two groups. This study supports the hypothesis that stress can influence the development of cancer, but that stress itself is not a sufficient factor for the development of cancer in rats. The study also provides new information for development of experimental studies and controlled environments.

Introduction

Stress is not an external stimulus, but rather an internal reaction of an organism to its environment.Citation1 Stress can be positive (eustress), as in conditions of danger, when the body reacts with alert behavior. By contrast, negative stress or “distress” occurs when the activation, intensity, and persistence of the stress results in physical and psychological disorders.Citation2,Citation3

Various studies have shown an association between stress and cancer and investigated the multiple effects exerted by stress on immune function; for example, during the diagnosis and treatment of the disease, some patients experience stress and depression that result in immune suppression.Citation4–Citation8 Similarly, patients with breast cancer have a decrease in their numbers of natural killer cells, and alterations in the secretion of cytokinesCitation9 and in DNA repair capacity.Citation10–Citation12 It has been shown in vitro that stress is involved in pathways of cancer progression such as immunoregulation, angiogenesis, and invasion.Citation13

During stress, the brain, endocrine system, and immune system form a circuit, communicating through systems such as neurotransmitters, neuropeptides, hormones, lymphoid tissue growth factors, cytokines, and eicosanoids.Citation8 Psychoneuroimmunology studies have revealed how much the immune system is affected by the influence of stress. The reactions are complex, involving different tissues and body system responses.Citation14,Citation15 The target organ responding to stress is the brain, and it determines the activity of other tissues by the action of hormones and immune receptors on pathway that alter brain function and regulate stress response. The physiological changes caused by stress are crucial, and the major components in these changes are corticotropin-releasing factor and the locus coeruleus of the brain.Citation16

The immune system is highly sensitive to changes in the body and the stimuli to which it is exposed. Immune function is often diminished by psychological stress,Citation8 but increases as a result of significant and positive events.Citation17,Citation18 Social support has been shown to be a factor that improves the outcome of patients with cancer, and may produce a better immune response, as it reduces the level of cortisol and restores the natural killer cell number and production of cytokines,Citation9,Citation11,Citation19,Citation20 whereas social isolation increases the risk of death associated with several chronic diseases.Citation6

The N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (NMU) rat model used in this study is considered to be one of the best animal models of cancer. Chemical induction of mammary cancer in rats has a number of features that make it very useful for investigating many aspects of breast cancer, for instance: 1) the time to tumor development is short; 2) tumors are generated mainly in the mammary gland (adenocarcinomas) as the cancer has limited metastatic potential; 3) the carcinogen causes little or no systemic toxic effect; and 4) the breast tumors produced have histologic origin and pathologic features that are similar to those of typical human breast cancer.Citation21,Citation22 In this model, we used a single intraperitoneal dose of 50 mg NMU/kg body weight.Citation21 In addition, the stress induced by isolation condition has some theoretical support, applicable to studies of live rodents,Citation5,Citation23–Citation25 and producing multiple physiological changes and behavioral effects.Citation8,Citation25 Finally, changes in tumor volume in animal models are often used to evaluate the effects of different factors on mammary gland carcinogenesis in female rats, because they may have important prognostic value for some malignancies, including breast cancer.Citation26

The objective of this study was to investigate whether stress caused by isolation of rats has an impact on the development of tumors, assessed by the volume and number of tumors, and the levels of corticosterone.

Methods

Animals

Breast cancer was induced by intraperitoneal administration of a single dose of 50 mg NMU/kg body weight in female Sprague Dawley rats aged 50±2 days, weighing 90±15 g (N=20).Citation27 This strain was chosen because studies have shown that it is an excellent model for the development and progression of breast cancer, as the rats naturally develop a diagnostic range similar to humans.Citation23,Citation28

Induction of cancer in rats

The carcinogen NMU (catalog number 684/93/5, product number N1517-isopac, PubChem Substance ID 24897498; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) is a model for chemical induction of mammary cancer in rats. It is an alkylating agent that acts directly on DNA, creating mutations.Citation29

Induction of stress in rats

A method for inducing stress by social isolation or deprivation was chosen. This model consists of isolating each of the rats in a cage, preventing any kind of social interaction with their peers, which leads to a pattern of apathy and chronic stress after approximately 10 weeks.Citation24,Citation25

Procedure

Twenty Sprague Dawley rats were injected with the carcinogen NMU.Citation21 At 51±2 days, the animals were divided into two groups of ten rats each. Rats belonging to the control group (cancer induction condition group) were allowed to remain together in a large cage, while the study group were exposed to both cancer induction and isolation stress (cancer induction and isolation condition, CIIC), so they were placed in individual cages, 12.5×14.5×26.5 cm in size, preventing social interaction with their peers. At 5 months of age, all rats were euthanized and the tumors removed. Tumor size was estimated using a Vernier caliper by two different methods: 1) taking into account only the larger diameter and 2) measuring three dimensions to give the approximate total volume. TNM classification was used (classification of the primary tumor size [T], node status or regional lymph nodes [N], and the presence of distant metastasis [M]).Citation30

Cancer type was confirmed by histopathological examination of paraffin wax-embedded sections from tumors of each subset of animals. Mammary tumors were classified according to Russo et al.Citation31 Corticosterone quantification was performed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using a commercial kit (Alpco, Salem, NH, USA, catalog number 55-CORMS-E01).

Statistical analysis

To assess the heterogeneity of the groups when comparing the number, diameter, and approximate total volume of the tumors that developed in the group, we used nonparametric analysis with the Mann–Whitney U-test for independent samples. We also used t-test for independent samples testing of corticosterone in rats.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Medical Sciences, University of Guanajuato. This study followed the criteria required by the Official Mexican Standard NOM-062-ZOO-1999 regarding animal husbandry (characteristics that comprise the laboratory animal research, the staff responsible for operational processes, the profile of technical staff involved in the care and use of the laboratory animals, obtaining of the animals, health and quality certificate, and the identification and registration of the thereof).Citation32

Results

It was observed that after 70 days, 100% of the rats that had received an injection of the carcinogen had developed at least one tumor. At the time of euthanasia, the control group had developed eleven tumors; nine rats (90%) had one tumor each, and one rat (10%) developed two tumors. By contrast, the rats in the experimental CIIC group had 16 tumors; six rats (60%) developed one tumor, two rats (20%) developed two tumors, and two rats (20%) developed three tumors. As shown in , the CIIC group tended to have a larger tumor volume, and more rats had more than one tumor, compared with the control group.

Table 1 Number, diameter, and volume of tumors in both rat groups

The between-group comparison groups revealed no significant differences in: 1) number of tumors or 2) the two methods of estimating tumor size used: i) larger diameter and ii) approximate volume of the tumors ().

Table 2 Comparison between both groups with the Mann–Whitney U-test, significant difference P<0.05

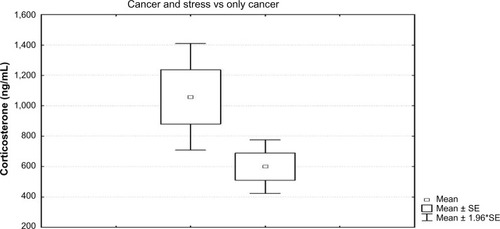

Level of corticosterone was significantly different between the CIIC and control groups (t=2.50; P=0.02). Higher corticosterone levels were found in the CIIC (1058.57 ng/mL ± standard error [SE] 1.96) than in the control (599.7 ng/mL ± SE 1.96) group (). The normal range of serum corticosterone in female rats is 292.5–819.0 ng/mL.Citation33

Figure 1 Comparison between the level of corticosterone in the group with CIC and CIIC.

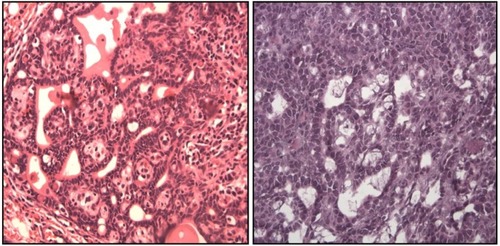

shows the histopathologic characteristics of representative tumors from each of the groups. The CIIC group exhibited cells with increased nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, indicating a more active process of division, which is a morphological criteria of malignancy. Further, to demonstrate the capacity of mammary tumor cells to respond to corticosterone, we performed immunohistochemistry and found that rat mammary tumors, including benign fibroadenomas, ductal carcinoma in situ, and invasive ductal carcinoma all expressed glucocorticoid receptors.

Figure 2 Histopathologic characteristics.

Abbreviations: CIC, cancer induction condition; CIIC, cancer induction and isolation condition.

Rats in the CIIC group also showed apathetic behavior (eg, stopped eating) and appeared fearful.

Discussion

The main objective of this research was to investigate whether stress caused by isolation could affect the development and size of tumors and the levels of corticosterone in rats. There were statistically significant differences in corticosterone levels between the two groups. Although both groups showed tumor development, the CIIC group had greater morphological damage, with larger tumor size and a higher number of multicentric tumors in each rat, and also more aggressive activity in invasive cancer as indicated by immunohistochemical studies. Moreover, anxious behavior was evident in the group with insulation. The lack of statistically significant difference may be due to the small size of the sample, causing a possible type II error.

The CIIC group also had higher levels of corticosterone. Similar findings were reported by Hermes et al,Citation23 who observed that mice kept in isolation developed significant dysregulation of corticosterone responses, while cancer recovery was markedly delayed, and this was associated with increased mammary tumor progression. Further, to demonstrate the capacity of mammary tumor cells to respond to corticosterone, they performed immunohistochemistry, and found that, rat mammary tumors, including benign fibroadenomas, ductal carcinoma in situ, and invasive ductal carcinoma all expressed glucocorticoid receptors.

Studies have evaluated multifocal and multicentric breast cancer tumors, and using (in addition to the TNM method) the aggregate tumor volume (ie, the summation of the diameter of all tumors found in a single quadrant or in different quadrants of the breast) have found that tumor size is a variable that can predict the existence of metastases in lymph axillary nodes.Citation34,Citation35 One research, however, suggests that the estimate of the approximate total tumor volume is a more successful predictor of metastatic potential than the use of: 1) the largest tumor diameter as the only estimate or 2) the aggregate tumor volume.Citation36 However, to obtain approximate total tumor volume, it is necessary to measure the tumor in three dimensions (length, width, and depth), and the calculation of the total volume is only possible in objects having regular surfaces. In the current study, we used both the TNM method and measurement of the estimated approximate total volume of the tumor.

During the study, we observed that the behavior of rats in response to isolation stress was different in individual rats; some resisted and struggled, trying to get out of the cage, whereas others showed apathetic behavior (such as ceasing to eat) and appeared fearful. Other studies have observed similar behavior in rats, associated with early exposure to stressors, glucocorticoid dynamics, and subsequent development of mammary tumors and cancer progression.Citation37,Citation38

It is likely that the behavioral responses seen in rats in this study are similar to those expressed by humans, although it is easier to control for variables within the laboratory, whereas studies on the influence of stress on cancer in humans relies on subjective evaluation of the event, performed by the individual patient and according to which the patient responds to stress.Citation39 However, these findings indicate a necessity to provide psychological and social support, along with strategies for stress reduction, for patients who are given a diagnosis of cancer.

The significant differences in the level of corticosterone seen in the two groups in this study support the hypothesis that stress can influence the development of cancer, but we cannot conclude that stress itself is a sufficient factor for the development of cancer in rats. Therefore, further research is needed to clarify the relationship between stress, the immune system, and cancer, using reliable and innovative experimental methods. Previous findings from various investigations that have studied the relationship between stress, the effects on the immune system, and how both of these influence the progression of cancer are controversial, owing to the complexity of studying these variables, because many factors may converge, and these must be weighed with extreme care.

The results of our study support those of previous studiesCitation5,Citation6,Citation23 showing that stress influences tumor development, and directly influences tumor size and corticosterone level. They also provide new information for development of controlled environments to measure experimental stress in cancer models and reduce interference from other variables.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Ugto-CA-37 PROMEP funding.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MoreraAGonzalez-de-RiveraJLRelación entre factores de estrés, depresión y enfermedad médicaPsiquis19834253260

- SzaboSHans Selye and the development of the stress concept. Special reference to gastroduodenal ulcerogenesisAnn N Y Acad Sci199885119279668601

- LopezD[Stress epidemic of the century: how to understand it and overcome]. Estres Epidemia del Siglo XXI: Como Entenderlo, Entenderse y Vencerlo4th edBuenos AiresLumen2005

- SephtonSEDhabharFSKeuroghlianASDepression, cortisol, and suppressed cell-mediated immunity in metastatic breast cancerBrain Behav Immun2009231148115519643176

- MaddenKSSzpunarMJBrownEBEarly impact of social isolation and breast tumor progression in miceBrain Behav Immun201330135141

- WilliamsJBMcDonoughMAHilliardMWWilliamsALCuniowskiPCGonzalezMGIntermethod reliability of real-time versus delayed videotaped evaluation of a high-fidelity medical simulation septic shock scenarioAcad Emerg Med20091688789319845552

- PowellNDTarrAJSheridanJFPsychosocial stress and inflammation in cancerBrain Behav Immun2013304147

- SegerstromSCMillerGEPsychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiryPsychol Bull2004130460163015250815

- Witek-JanusekLAlbuquerqueKChroniakKRChroniakCDurazo-ArvizuRMathewsHLEffect of mindfulness based stress reduction on immune function, quality of life and coping in women newly diagnosed with early stage breast cancerBrain Behav Immun200822696998118359186

- Kiecolt-GlaserJKStephensRELipetzPDSpeicherCEGlaserRDistress and DNA repair in human lymphocytesJ Behav Med1985843113202936891

- Kiecolt-GlaserJKRoblesTFHeffnerKLLovingTJGlaserRPsycho-oncology and cancer: psychoneuroimmunology and cancerAnn Oncol200213Suppl 4S165S169

- AndersenBLFarrarWBGolden-KreutzDStress and immune responses after surgical treatment for regional breast cancerJ Natl Cancer Inst199890130369428780

- LutgendorfSKSoodAKAntoniMHHost factors and cancer progression: biobehavioral signaling pathways and interventionsJ Clin Oncol201028264094409920644093

- SánchezMGonzálezRMCosYMacíasC[Stress and immune system]. Estres y sistema inmuneRev Cubana Hematol Inmunol Hemoter200723

- Vera-VaillarroelPEVela-CasalG[Psychoneuroimmunology: relationships between psychological and immunological human factors]. Psiconeuroinmunología: relaciones entre factores psicológicos e inmunitarios en humanosRev Latinoam Psicol1999312271289

- OrlandiniA[Stress: What is and how to avoid it Mexico: Economic Culture Fund] El Estres: Que es y como evitarloMéxicoFondo de Cultura Economica1999

- ReicheEMNunesSOMorimotoHKStress, depression, the immune system, and cancerLancet Oncol200451061762515465465

- SireraRSánchezPCampsCInmunología, estres, depresion y cancerPsicooncologia200633548

- BlombergBBAlvarezJPDiazAPsychosocial adaptation and cellular immunity in breast cancer patients in the weeks after surgery: an exploratory studyJ Psychosom Res200967536937619837199

- AntoniMHLechnerSDiazACognitive behavioral stress management effects on psychosocial and physiological adaptation in women undergoing treatment for breast cancerBrain Behav Immun200923558059118835434

- Garcia-SolisPAcevesC[Study of nutritional factors associated with the prevention of breast cancer. Importance of animal models]. Estudio de los factores nutricionales asociados a la prevención de cáncer mamario. Importancia de los modelos animalesArch Latinoam Nutr20055521122516454047

- De la Roca-ChiapasJMCordova-FragaTSabaneroGBAplicaciones interdisciplinaria entre fisica, medicina y psicologiaActa Universitaria2009197175

- HermesGLDelgadoBTretiakovaMSocial isolation dys-regulates endocrine and behavioral stress while increasing malignant burden of spontaneous mammary tumorsProc Natl Acad Sci U S A200910652223932239820018726

- HiscoxDNHusbandRFPerryMCSurvival, bodyweight and food consumption data obtained from life span rodent studies in isolated animal unitsArch Toxicol Suppl198363573606578743

- TakemotoTISuzukiTMiyamaTEffects of isolation on mice in relation to age and sexTohoku J Exp Med197511721531651209605

- MôcikovákMníchovaMKubatkaPBojkováBAhlersIAhlersováEMammary carcinogenesis induced in WistanHan rats by the combination of ionizing radiation and dimethylbenz (a) anthracene: prevention with melatoninNeoplasma200047422722911043826

- Garcia-SolisPAlfaroYAnguianoBInhibition of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mammary carcinogenesis by molecular iodine (I2) but not by iodide (I-) treatment: evidence that I2 prevents cancer promotionMol Cell Endocrinol20052361–2495715922087

- DavisRKStevensonGTBuschKATumor incidence in normal Sprague-Dawley female ratsCancer Res195616319419713304860

- ThompsonHMethods for the induction of mammary carcinogenesis in the rat using either 7,12-Dimethylbenz[α]anthracene or 1-methyl-1-nitrosureaMethods in Mammary Gland Biology and Breast Cancer ResearchNew YorkKluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers20001929

- GreenFLAJCC Cancer Staging Handbook: from the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual6th edNew YorkSpringer2002

- RussoJRussoIHRogersAEVan ZwietenMJGustersonBTumors of mammary glandTurusovVMohrUPathology of Tumours in Laboratory AnimalsLyonIARC Scientific Publications199014778

- NOM-062-ZOO-1999, NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-062-ZOO-1999[Technical specifications for production, care and use of animals of laboratory]. Especificaciones Tecnicas Para La Produccion, Cuidado Y Uso De Los Animales De LaboratorioMexico1999

- ALPCO, mouse and rat corticosterone ELISAFor the quantitative determination of corticosterone in rat and mouse serum or plasma Catalog number: 55-CORMS-E012013

- CoombsNJBoyagesJMultifocal and multicentric breast cancer: does each focus matter?J Clin Oncol200523307497750216234516

- AndeaAAWallisTNewmanLABouwmanDDeyJVisscherDWPathologic analysis of tumor size and lymph node status in multifocal/multicentric breast carcinomaCancer20029451383139011920492

- AndeaAABouwmanDWallisTVisscherDWCorrelation of tumor volume and surface area with lymph node status in patients with multifocal/multicentric breast carcinomaCancer20041001202714692020

- CavigelliSAYeeJRMcClintockMKInfant temperament predicts life span in female rats that develop spontaneous tumorsHorm Behav200650345446216836996

- YeeJRCavigelliSADelgadoBMcClintockMKReciprocal affiliation among adolescent rats during a mild group stressor predicts mammary tumors and lifespanPsychosom Med20087091050105918842748

- McEwenBSProtective and damaging effects of stress mediatorsN Engl J Med199833831711799428819