Abstract

Purpose

Caregivers have expressed interest in survey research, yet there is limited information available about survey response burden, ie, the time, effort, and other demands needed to complete the survey. This may be particularly important for caregivers due to excessive time demands and/or stress associated with caregiving.

Method

Survey response burden indicators were collected as part of a study to develop and validate a patient-reported outcome (PRO) measurement system for caregivers of civilians or service members/veterans (SMVs) with traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Results

Compared to the group caring for civilians (n=335), the group caring for SMVs (n=123) was comprised of all women, was younger, had fewer racial/ethnic minorities, had more education, and nearly all were the spouse of a person with TBI. All PRO outcomes were poorer for the group caring for SMVs. Although the caregivers of SMVs had poorer PRO outcomes compared to caregivers of civilians, they were more likely to report that they would recommend the study to others. Caregivers with less education and those from racial/ethnic minority groups had more favorable ratings of their study participation experience, even though they needed more help using the computer or answering the questions.

Conclusion

The results of this study provide useful information about the acceptability of computer-based survey administration for caregiver PROs. PROs are widely gathered in clinical and health services research and could be particularly useful in TBI care programs. More data are needed to determine the best assessment strategies for individuals with lower education who are likely to require some assistance completing PRO surveys. Studies evaluating PROs administered by multimedia platforms could help researchers and clinicians plan the best strategies for assessing health-related quality of life in TBI caregivers.

Introduction

Caregivers of people with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) are at risk for poor health-related quality life (HRQOL).Citation1–Citation7 Caregivers of service members or veterans (SMVs) with TBI face unique challenges navigating the military health care system, and may experience even greater burden and worse HRQOL than caregivers of civilians with TBI.Citation5,Citation8–Citation13 Assessing HRQOL in caregivers of individuals with TBI is complicated by the lack of a gold standard assessment tool specific to this population. To address this need, the TBI-CareQOL study developed a patient-reported outcome (PRO) measurement system that captures both the generic and unique aspects of HRQOL significant to caregivers of civilians or SMVs with TBI.Citation4,Citation5,Citation14 Briefly, TBI-CareQOL measurement development involved qualitative methods to identify relevant aspects of HRQOL for both caregivers of civilians and SMVs. Areas requiring new development included several iterations of item development and review. Quantitative field testing of items was conducted, and detailed analyses included both classical test theory approaches and item response theory analytical approaches for final item selection. The study utilized modern psychometric and health information technology methods from PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System).Citation15

Health information technology advances have increased the number of available PRO survey administration options. However, different methods of administration require different skills and resources of people being asked to complete the survey; this means that the choice of method of administration may result in differing levels of respondent burden.Citation16 One important methodological standard for a PRO instrument is to minimize respondent burden, ie, the time, effort, and other demands needed to complete the instrument.Citation17–Citation21 This may be particularly important for caregivers due to excessive time demands and/or stress associated with caregiving.Citation22–Citation24 Caregivers have expressed interest in survey research,Citation4,Citation5,Citation25 yet there is limited information available about respondent burden.Citation26 In addition to addressing item wording, literacy level, questionnaire length, and questionnaire formatting during instrument development, it is useful to obtain respondent feedback after completion of the questionnaire.Citation19,Citation27–Citation29

As part of the TBI-CareQOL study to develop and validate a PRO measurement system for TBI caregivers, respondents were asked to complete a short evaluation survey at the end of the online assessment. The purpose of this paper is to present the results of this evaluation survey, which included indicators of response burden. It was hypothesized that caregivers with less education would report more burden completing online computer surveys compared to those with more education. There were no specific hypotheses about response burden for caregivers of civilians vs SMVs or for racial/ethnic minorities, although there was interest in evaluating burden across these subgroups.

Methods

Participants

Caregivers of civilians with TBI were recruited from the Kessler Foundation, the Rehabilitation Institute of Michigan (RIM), The Institute for Rehabilitation and Research (TIRR) Memorial Hermann Rehabilitation Hospital, and the University of Michigan Medical School. Caregivers of SMVs with TBI were recruited primarily through military caregiver support organizations, eg, Hearts of Valor. Multiple recruitment strategies for convenience sampling were implemented, including existing TBI caregiver databases, medical record data capture systems,Citation30 and hospital-based and community outreach efforts. For both groups, caregivers were at least 18 years old, English-speaking, and were caring for an individual who sustained a medically documented TBI after age of 16 years. The individual with the TBI had to be at least 1 year post-injury. The TIRR Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved a waiver of consent because this research was considered to be of low risk. The Kessler Foundation IRB, RIM: Wayne State University IRB, and the University of Michigan Medical School IRB approved both a waiver of written informed consent (to allow for telephone consent) as well as in-person written consent. Each participant received US$50 for completing the study.

Measures and method of administration

Sociodemographic data were obtained by self-report on the survey, and information about the person with TBI was obtained by medical record review or by caregiver report. The Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory-Fourth Edition (MPAI-4)Citation31 was completed by caregivers as a measure of the functional ability of the person with TBI. MPAI-4 items represent the range of physical, cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social problems that people may encounter after an acquired brain injury. MPAI-4 scores were dichotomized to indicate low functioning/more impairment (score ≥60) vs high functioning/less impairment (score <60).Citation32 Caregivers completed four TBI-CareQOL item pools; all items were written at approximately a fifth-grade reading level. The 66-item Caregiver Strain item pool captured feelings of being overwhelmed, stressed, self-defeated, downtrodden, and “beat-down” related to the caregiver role. The 81-item Caregiver-Specific Anxiety item pool captured feelings of worry and anxiety specific to general safety, health, and future well-being of the person with the injury. The 28-item Feeling Trapped item pool captured feelings of being unable to go places or do things due to caregiving responsibilities. The 98-item Feelings of Loss item pool captured feelings of loss for the caregivers themselves (including loss of self, relationships, activities, and future plans) and feelings of loss with regard to the person with TBI (including loss of abilities, loss of potential/failure, and changes in behavior/personality).

Participants next completed 10 measures from PROMISCitation15 which used approximately a sixth-grade reading level for most items.Citation33 The PROMIS measures were Depression (feelings of sadness and worthlessness), Anxiety (fear, anxiety, and hyperarousal), Anger (irritability and frustration), Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities (involvement in one’s usual social roles and activities), Satisfaction with Social Roles and Activities (satisfaction in one’s usual social roles and activities), Emotional Support (feelings of being cared for and having supportive relationships), Informational Support (ability to access helpful information and advice), Social Isolation (feelings of being emotionally cut off from other people), Fatigue (feelings of tiredness and exhaustion related to being overwhelmed), and Sleep Disturbance (sleep quality, depth, and restorative sleep). All PROMIS measures were administered as computer-adaptive tests. Additional instruments were administered in this study, but were not included in this paper.

Participants were asked to complete PRO surveys through the PROMIS Assessment Center online platform (http://www.assessmentcenter.net), either at a designated computer at the site or on their own computer. After all PROs were completed, a short five-item evaluation survey was presented: 1) “Compared to what you expected, how would you rate your experience participating in this research study?” (a lot worse than expected, a little worse than expected, about the same as expected, a little better than expected, a lot better than expected); 2) “Would you recommend this research study to other people?” (no, maybe, yes); 3) “Do you have any comments or suggestions?” (open-ended); 4) “What is your overall rating of the design of the screens, including the colors and the layout?” (poor, fair, good, very good, excellent); and 5) “Did you receive any help using the computer or answering any of the questions?” (not at all, a little bit, some, a lot). Since these five evaluation questions were presented at the end of the online assessment, they were not presented to participants who stopped before completing all of the PRO surveys. Two or three of the authors independently coded responses to the open-ended evaluation question; all three coders met to resolve all discrepancies. Participant responses were coded as positive, negative, psychological, or other. Responses were coded as “positive” if most of the content of the response indicated that the participant had a positive opinion of the study and/or questionnaires, eg, “I think I learned a lot about myself.” Brief comments like “thank you” or “good luck” were also coded as “positive.” Responses were coded as “negative” if most of the content of the response indicated that the participant had a negative opinion of the study and/or questionnaires, eg, “I think the survey was a little too long.” Responses were coded as “psychological” if the participant “told a story” without content relevant to study burden, eg, “My daughter is in a nursing home and doesn’t go out much.” Responses were coded as “other” if they did not fit into the other categories, eg, “Make a mobile version.” If a response included multiple themes, classification as positive or negative took precedence. The amount of time needed to complete the surveys was automatically recorded by the assessment platform.

Statistical analysis

Item response theory-based scores for all TBI-CareQOL and PROMIS measures were standardized using T-scores (M=50, SD=10)Citation15; higher scores indicate more of the trait being measured. Thus, for negative traits (Caregiver Strain, Caregiver-Specific Anxiety, Feeling Trapped, Feelings of Loss, Depression, Anxiety, Anger, Social Isolation, Fatigue, Sleep Disturbance), higher scores indicate worse HRQOL, whereas for positive traits (Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities, Satisfaction with Social Roles and Activities, Emotional Support, Informational Support) higher scores indicate better HRQOL.

The total time to complete the assessment was greater than 3 hours for 31% of the participants (n=140). Since many of these participants had data that spanned across multiple days, it was assumed that these individuals took breaks; thus, they were excluded from analyses that examined number of minutes for completion. Chi-squared tests, Fisher’s exact tests, and analysis of variance methods were used to compare the two caregiver groups on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, PROs, and response burden indicators. Separate multivariable logistic regression models were estimated to evaluate the effects of caregiver group, education (more than high school vs less education), race/ethnicity (non-His-panic white vs others), MPAI-4 (low vs high functioning), and PROs on study participation experience (a little/a lot better vs same/worse), study recommendation (yes vs no/maybe), and help completing the assessment (some/a little/a lot vs none). ORs and 95% CIs were estimated. A chi-squared test was used to evaluate the association between help provided in completing the assessment and evaluation comments (positive vs negative vs psychological/other). A nominal significance level of 0.05 was used to interpret the results.

Results

Of the 473 individuals who were enrolled in the TBI-CareQOL study, 458 participants (97%) completed the evaluation questions at the end of the assessment and were included in the analyses; 335 were caregivers for civilians with TBI and 123 were caregivers for SMVs with TBI. The two groups were very different (). Compared to the group caring for civilians, the group caring for SMVs was comprised of all women, was younger, had fewer racial/ethnic minorities, had more education, and nearly all were the spouse of a person with TBI (all P<0.001). There was a higher proportion of low functioning SMVs compared to civilians (51% vs 12%; P<0.001). All HRQOL outcomes were poorer for the group caring for SMVs (all P<0.001).

Table 1 Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and health-related quality of life outcomes of study participants, by caregiver type

summarizes information about the survey evaluation and response burden indicators. About half in each caregiver group reported that their study participation experience was about the same as expected, and about half reported that their experience was better than expected; only 6% in each group reported that their experience was worse than expected. The group caring for SMVs was more likely to report that they would recommend this study to others (P=0.002), and they were more likely to have comments about their study participation (P=0.006). Among those who had comments, about half in each group had negative comments. About half in each group rated the screen design as very good or excellent. The group caring for civilians needed more help to complete the questionnaires (P=0.03) but took about the same length of time to complete them as the group caring for SMVs.

Table 2 Survey evaluation and response burden, by caregiver type

Caregivers were more likely to rate their study participation experience as a little/a lot better than expected if they had lower education or were racial/ethnic minorities (). Caregiver group, MPAI-4 function, and HRQOL outcomes were not associated with study participation experience (all P>0.10).The group caring for SMVs was more likely to report that they would recommend this study to others. Education, race/ethnicity, MPAI-4 function, and HRQOL outcomes were not associated with study recommendation (all P>0.10).

Table 3 Logistic regression models for evaluation/burden indicators

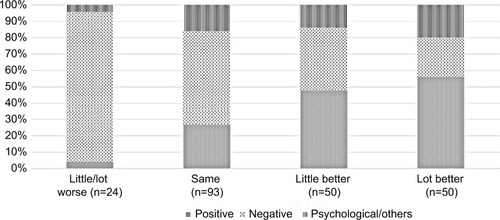

Participants with a more favorable overall rating of their study participation experience had a greater proportion of positive comments compared to those with less favorable ratings (; P<0.001). Specifically, 56% and 48%, respectively, of those who rated their experience as a lot better or a little better than expected had positive comments compared to 4% and 27%, respectively, for those who rated their experience as worse or about the same.

Figure 1 Association between rating of study participation experience and open-ended comments (P<0.001).

Those with less education and those from racial/ethnic minority groups needed more help using the computer or answering questions (). Caregiver group, MPAI-4 function, and HRQOL outcomes were not associated with the need for help (all P>0.10).

Discussion

Participant ratings of survey response burden provide useful information for researchers and clinicians on the acceptability of a PRO instrument for a particular population and use. This is the first study to measure multiple indicators of PRO survey response burden in caregivers of civilians and SMVs with TBI. Overall, caregivers had generally favorable ratings of study participation experience, most would recommend the study to others, and most needed little help using the computer or answering the questions. Multivariable analyses of these burden indicators showed that caregivers with less education and those from racial/ethnic minority groups had more favorable ratings of their study participation experience, even though they needed more help using the computer or answering the questions. Receiving help with survey completion allowed them to participate successfully in the study. It is possible that some individuals may consider survey participation as a form of social support.

Although caregivers of SMVs in this study had poorer HRQOL outcomes compared to caregivers of civilians, they were more likely to report that they would recommend the study to others. HRQOL outcomes were not associated with study recommendations. It may be that these caregivers were simply more appreciative to be the focus of research efforts designed to better understand and ultimately improve their HRQOL. Anecdotally, many caregivers mentioned that they have few opportunities to participate in research. In addition, qualitative data suggest that caregivers of SMVs often do not feel like they have the opportunity to express their emotions, and in fact they feel the need to put on a brave face for others.Citation5 Thus, it may also be possible that providing them with the opportunity and a relatively anonymous space to express their feelings might have been cathartic and may have led them to recommend this study to others.

There are some limitations to this study. Because convenience sampling was used, generalizability is limited with regard to racial/ethnic minorities, male caregivers, and caregivers who are parents or relations other than spouses. Caregivers of SMVs were primarily recruited through support organizations, and so results may not be representative of those who care for a person with a military-related TBI. It will be important to recruit caregivers through military medical centers in future studies. In addition, SMVs with TBI have high rates of other comorbid clinical conditionsCitation34 which could increase the caregiver burden. Comorbidities were not collected for this study, but would be important to incorporate in the design of future studies. The majority of the caregivers completed the survey at home; thus, it is possible that their survey evaluation was influenced by others.

PROs are widely gathered in clinical and health services research; they are increasingly collected and used in clinical practice settings as well.Citation35–Citation40 PROs are relevant for many activities: helping patients and their clinicians make informed decisions about health care, monitoring the progress of care, setting policies for coverage and reimbursement of health services, improving the quality of health care services, and tracking or reporting on the performance of health care delivery organizations.Citation21 It might be useful to incorporate PROs into the TBI care programs developed by the Department of Defense and the Veterans Affairs Health Care Systems.Citation41

The TBI-CareQOL measurement system offers unique measures of caregiver-specific HRQOL. The results of this study provide useful information about the acceptability of computer-based survey administration in caregivers of civilians and SMVs. Future work could consider adapting the TBI-CareQOL measurement system for caregivers of people with other conditions, eg, Alzheimer’s disease. More data are needed to determine the best assessment strategies for individuals with lower education who are likely to require some assistance in completing PRO surveys. For example, studies evaluating PROs administered by multimedia platformsCitation42–Citation47 could help researchers and clinicians plan the best strategies for assessing HRQOL in TBI caregivers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research under Grant #R01-NR013658.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- VerhaegheSDefloorTGrypdonckMStress and coping among families of patients with traumatic brain injury: a review of the literatureJ Clin Nurs20051481004101216102152

- ChronisterJChanFSasson-GelmanEJChiuCYThe association of stress-coping variables to quality of life among caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injuryNeuroRehabilitation2010271496220634600

- KratzACarlozziNBrickellTASanderAM“I Want ME as a Caregiver”: perspectives from caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injuryArch Phys Med Rehabil20149510e50

- CarlozziNEKratzALSanderAMHealth-related quality of life in caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury: development of a conceptual modelArch Phys Med Rehabil201596110511325239281

- CarlozziNEBrickellTAFrenchLMCaring for our wounded warriors: a qualitative examination of health-related quality of life in caregivers of individuals with military-related traumatic brain injuryJ Rehabil Res Dev201653666968027997672

- SabanKLGriffinJMUrbanAJanusekMAPapeTLCollinsEPerceived health, caregiver burden, and quality of life in women partners providing care to Veterans with traumatic brain injuryJ Rehabil Res Dev201653668169227997670

- GriffinJMLeeMKBangerterLRBurden and mental health among caregivers of veterans with traumatic brain injury/polytraumaAm J Orthopsychiatry201787213914828206801

- TaftCTSchummJAPanuzioJProctorSPAn examination of family adjustment among Operation Desert Storm veteransJ Consult Clin Psychol200876464865618665692

- RuffRLRuffSSWangXFImproving sleep: initial headache treatment in OIF/OEF veterans with blast-induced mild traumatic brain injuryJ Rehabil Res Dev2009469107120437313

- LesterPPetersonKReevesJThe long war and parental combat deployment: effects on military children and at-home spousesJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry201049431032020410724

- MansfieldAJKaufmanJSMarshallSWGaynesBNMorrisseyJPEngelCCDeployment and the use of mental health services among U.S. Army wivesN Engl J Med2010362210110920071699

- PhelanSMGriffinJMHellerstedtWLPerceived stigma, strain, and mental health among caregivers of veterans with traumatic brain injuryDisabil Health J20114317718421723524

- CarlozziNELangeRTFrenchLMSanderAMFreedmanJBrickellTAA latent content analysis of barriers and supports to healthcare: perspectives from caregivers of service members and veterans with military-related traumatic brain injuryJ Head Trauma Rehabil Epub2018130

- CarlozziNEKallenMAHanksRThe TBI-CareQOL measurement system: development and validation of health-related quality of life measures for caregivers of civilians and service members/veterans with traumatic brain injuryArch Phys Med Rehabil Epub2018906

- CellaDRileyWStoneAThe Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008J Clin Epidemiol201063111179119420685078

- BowlingAMode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data qualityJ Public Health2005273281291

- AaronsonNAlonsoJBurnamAAssessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteriaQual Life Res200211319320512074258

- US Food and Drug AdministrationGuidance for industryPatient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims2009 Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm193282.pdfAccessed October 03, 2018

- GrovesRMSurvey Methodology2nd edHoboken, NJJohn Wiley2009

- DillmanDASmythJDChristianLMInternet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method4th edHoboken, NJWiley & Sons2014

- CellaDHahnEAJensenSEPatient-Reported Outcomes in Performance MeasurementPublication No. BK-0014-1509Research Triangle Park, NCRTI Press2015 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424378/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK424378.pdfAccessed August 22, 2018

- DuraJRKiecolt-GlaserJKSample bias in caregiving researchJ Gerontol1990455P200P2042394916

- WeitznerMAJacobsenPBWagnerHFriedlandJCoxCThe Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) scale: development and validation of an instrument to measure quality of life of the family caregiver of patients with cancerQual Life Res199981–2556310457738

- NaborsNSeacatJRosenthalMPredictors of caregiver burden following traumatic brain injuryBrain Inj200216121039105012487718

- WilliamsCJShusterJLClayOJBurgioKLInterest in research participation among hospice patients, caregivers, and ambulatory senior citizens: practical barriers or ethical constraints?J Palliat Med20069496897416910811

- DeekenJFTaylorKLManganPYabroffKRInghamJMCare for the caregivers: a review of self-report instruments developed to measure the burden, needs, and quality of life of informal caregiversJ Pain Symptom Manage200326492295314527761

- FayersPMMachinDQuality of Life: The Assessment, Analysis and Interpretation of Patient-Reported Outcomes2nd edChichester, EnglandJohn Wiley & Sons2007

- RolstadSAdlerJRydénAResponse burden and questionnaire length: is shorter better? A review and meta-analysisValue Health20111481101110822152180

- BlairJCzajaRFBlairEADesigning Surveys: A Guide to Decisions and Procedures3rd edThousand Oaks, CASage Publications2014

- HanauerDAMeiQLawJKhannaRZhengKSupporting information retrieval from electronic health records: a report of University of Michigan’s nine-year experience in developing and using the Electronic Medical Record Search Engine (EMERSE)J Biomed Inform20155529030025979153

- MalecJFKragnessMEvansRWFinlayKLKentALezakMDFurther psychometric evaluation and revision of the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory in a national sampleJ Head Trauma Rehabil200318647949214707878

- MalecJ webpage on the InternetThe Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory: the center for outcome measurement in brain injury2005 Available from: http://www.tbims.org/combi/mpaiAccessed June 25, 2018

- DeWaltDARothrockNYountSStoneAAPROMIS Cooperative GroupEvaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item reviewMed Care2007455 Suppl 1S12S2117443114

- LangeRTBrickellTAKennedyJEFactors influencing post-concussion and posttraumatic stress symptom reporting following military-related concurrent polytrauma and traumatic brain injuryArch Clin Neuropsychol201429432934724723461

- LohrKNZebrackBJUsing patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: challenges and opportunitiesQual Life Res20091819910719034690

- DonaldsonMSTaking PROs and patient-centered care seriously: incremental and disruptive ideas for incorporating PROs in oncology practiceQual Life Res200817101323133018991021

- Feldman-StewartDBrundageMDA conceptual framework for patient-provider communication: a tool in the PRO research tool boxQual Life Res200918110911419043804

- GreenhalghJThe applications of PROs in clinical practice: what are they, do they work, and why?Qual Life Res200918111512319105048

- RoseMBezjakALogistics of collecting patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in clinical practice: an overview and practical examplesQual Life Res200918112513619152119

- AaronsonNKSnyderCUsing patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: proceedings of an International Society of Quality of Life Research conferenceQual Life Res200817101295129519048409

- The National Defense Authorization Act of 2007 (NDAA) [webpage on the Internet]John Warner National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2007, The National Defense Authorization Act of 2007 (NDAA), Section 744: TBI Family Caregiver Curriculum (FCC) [H.R. 5122];2007 Available from: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/109/hr5122/textAccessed August 22, 2018

- HahnEACellaDHealth outcomes assessment in vulnerable populations: measurement challenges and recommendationsArch Phys Med Rehabil2003844 Suppl 2S35S42

- HahnEACellalDDobrezDGQuality of life assessment for low literacy Latinos: a new multimedia program for self-administrationJ Oncol Manag2003125912

- HahnEACellaDDobrezDThe talking touchscreen: a new approach to outcomes assessment in low literacyPsychooncology2004132869514872527

- YostKJWebsterKBakerDWJacobsEAAndersonAHahnEAAcceptability of the talking touchscreen for health literacy assessmentJ Health Commun201015Suppl 2809220845195

- HahnEAChoiSWGriffithJWYostKJBakerDWHealth literacy assessment using talking touchscreen technology (Health LiTT): a new item response theory-based measure of health literacyJ Health Commun201116Suppl 315016221951249

- HahnEABurnsJLJacobsEAHealth literacy and patient-reported outcomes: a cross-sectional study of underserved English- and Spanish-speaking patients with type 2 diabetesJ Health Commun201520Suppl 2415