Abstract

Background

There is a need for a survey instrument to measure arthralgia (joint pain) that has been psychometrically validated in the context of existing reference instruments. We developed the 16-item Patient-Reported Arthralgia Inventory (PRAI) to measure arthralgia severity in 16 joints, in the context of a longitudinal cohort study to assess aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgia in breast cancer survivors and arthralgia in postmenopausal women without breast cancer. We sought to evaluate the reliability and validity of the PRAI instrument in these populations, as well as to examine the relationship of patient-reported morning stiffness and arthralgia.

Methods

We administered the PRAI on paper in 294 women (94 initiating aromatase inhibitor therapy and 200 postmenopausal women without breast cancer) at weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, and 52, as well as once in 36 women who had taken but were no longer taking aromatase inhibitor therapy.

Results

Cronbach’s alpha was 0.9 for internal consistency of the PRAI. Intraclass correlation coefficients of test-retest reliability were in the range of 0.87–0.96 over repeated PRAI administrations; arthralgia severity was higher in the non-cancer group at baseline than at subsequent assessments. Women with joint comorbidities tended to have higher PRAI scores than those without (estimated difference in mean scores: −0.3, 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.5, −0.2; P<0.001). The PRAI was highly correlated with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Endocrine Subscale item “I have pain in my joints” (reference instrument; Spearman r range: 0.76–0.82). Greater arthralgia severity on the PRAI was also related to decreased physical function (r=−0.47, 95% CI −0.55, −0.37; P<0.001), higher pain interference (r=0.65, 95% CI 0.57–0.72; P<0.001), less active performance status (estimated difference in location (−0.6, 95% CI −0.9, −0.4; P<0.001), and increased morning stiffness duration (r=0.62, 95% CI 0.54–0.69; P<0.0001).

Conclusion

We conclude that the psychometric properties of the PRAI are satisfactory for measuring arthralgia severity.

Introduction

The Menopause Quality of Life/Breast Cancer Adjuvant Therapy longitudinal cohort study was initiated in 2009 to investigate arthralgia (defined as inflammatory or non-inflammatory joint pain) in postmenopausal women without breast cancer and in women undergoing aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy. Since 2006, AIs have been the standard of care to prevent recurrence of hormone-sensitive early breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Arthralgia occurs more frequently with age,Citation1,Citation2 and is a noted secondary effect of AIs.Citation3–Citation6

While several validated instruments exist to measure arthritis (inflammatory joint pain),Citation7–Citation15 options for measuring arthralgia are limited. Because it may be non-inflammatory, arthralgia might not manifest signs that are readily measurable by a clinician. Hence, finding external and objective clinical criteria to measure arthralgia effectively poses even more of a challenge than it does for arthritis. Clinical arthritis assessments such as the Disease Activity Index for Rheumatoid ArthritisCitation16 are made up of subscales of tender and swollen joint counts. Among rheumatoid arthritis patients, Pearson correlation coefficients for clinician–patient agreement on tender and swollen joint counts have been estimated in meta-analysis to be 0.61 (tender) and 0.44 (swollen).Citation17 Thus, even with inflammatory joint pain, which has an externally observable component, patients’ self-assessments are often quite different from clinicians’ evaluations.

Magnetic resonance imaging may reveal disease processes of AI-associated arthralgia.Citation18–Citation20 However, as is often the case with the measurement of pain, no simple low-cost clinical test or biomarker for arthralgia is available for use in regular clinical practice. In addition, the role of inflammation and other biomarkers in arthralgia remains unclear; past efforts have been unsuccessful in validating patient-reported arthritis pain instruments against erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, antinuclear antibodies, anti-double-stranded DNA, anticyclic citrullinated peptide, rheumatoid factor, and uric acid.Citation21,Citation22 Therefore, the vast majority of research and clinical practice must rely on patient reports for assessment of arthralgia.

The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis IndexCitation7 and Joint-Specific Multidimensional Assessment of PainCitation23 measure pain intensity and affect, but in only one joint at a time (eg, knees). The Joint-Specific Multidimensional Assessment of Pain includes ten items per joint queried. These scales do not allow one to study arthralgia in multiple joints simultaneously, yet arthralgia was observed to occur in more than one joint location in the Breast Cancer Adjuvant Therapy cohort study.Citation5 Querying only one specific joint or bilateral joint pair could miss potential statistically or clinically significant arthralgia in other areas of the body. The Regional Pain Scale comes closer to measuring the construct of pain throughout the body, but queries pain severity in both nonarticular and articular regions. The Regional Pain Scale has only four response options (none, mild, moderate, or severe),Citation24 while 11-point (0–10) numeric rating scales have been demonstrated in past methodological research to have a higher degree of sensitivity and validity for pain assessment.Citation25

A reliable and valid measure of arthralgia severity is needed to assemble consistent epidemiological outcomes information about prevalence, incidence, time to onset, risk factors, severity, and duration of arthralgia, as well as to better understand the role of arthralgia in the effectiveness of AI treatment and the relationship between inflammation and AI-associated arthralgia. Such a measure is also needed to develop AI adherence interventions based on arthralgia management strategies; improving management of arthralgia has been suggested as the key to promoting AI adherence.Citation26

In order to address the need for a valid and reliable arthralgia severity measurement instrument, we developed the Patient-Reported Arthralgia Inventory (PRAI) in the context of a longitudinal cohort study of arthralgia, health-related quality of life, and medication adherence. We adapted the PRAI from the articular regions of the Regional Pain Scale in collaboration with its author,Citation24 revising the response options to follow best practices in patient-reported outcome measurementCitation27 and pain measurement. The PRAI uses a 0–10 numeric rating scale to assess pain severity over a recall period of the preceding 7 days. Our objectives were to evaluate the psychometric properties of the PRAI, assessing the scale’s reliability and construct validity, and exploring how duration of morning stiffness relates to arthralgia.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

Survey data were collected in a longitudinal prospective cohort study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00954564), with 52 weeks of follow-up per participant. Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant. The study was approved by the Vanderbilt University institutional review board and consisted of self-administered paper questionnaires completed at weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 52. Study personnel at Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt Institute for Medicine and Public Health, and Vanderbilt Women’s Health Research conducted the screening, enrollment, data collection, and analysis. Data were managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).Citation28

Participants

We recruited participants into three groups: women initiating AIs, women who had taken AIs but were no longer on AI therapy, and postmenopausal women who had never been diagnosed with breast cancer (comparison group). We chose these three groups to serve the aims of our parent study’s program of research to understand the time course and duration of treatment-emergent arthralgia with regard to AI initiation and cessation. Because arthralgia is common in postmenopausal women irrespective of breast cancer diagnosis or endocrine therapy (affecting 45%–55% of the population),Citation1,Citation2 the comparison group was selected to assess the background rate of arthralgia in menopause, thus helping us quantify treatment-emergent arthralgia severity in the parent study. Participants were recruited either by their treating physician at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center or via study advertisements in the greater Nashville area between 2009 and 2013. Participants in all groups had to be female, postmenopausal (self-report of at least 12 months without a menstrual period, unrelated to surgery or medication), 35–90 years of age, and have active self-reported performance status (≤3).Citation29

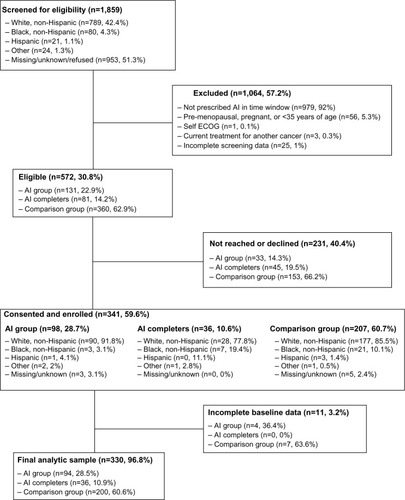

Participants in the first group had to initiate anastrozole, exemestane, or letrozole within 30 days of baseline assessment. Those in the second group had to have taken one of these three medications in the past and since discontinued for any reason. Comparison group participants had to acknowledge never having been told by a physician that they had breast cancer. Patients were ineligible if they were undergoing treatment for any other (nonbreast) cancer, were unable to provide informed consent, did not speak English, were pregnant, or had metastatic disease. Screening was done by telephone or via online self-administration. For the group of women who had stopped taking AIs, only a baseline survey was administered. Follow-up for the longitudinal AI and comparison groups was done by telephone and mail contact to assist participants in staying on schedule. Women were considered lost to follow-up if they had missed more than two surveys in a row and could not be reached after six attempts. Cohort screening and enrollment, as well as the derivation of the final analytic sample, are shown in .

Variables

We developed and administered the PRAI for the purpose of measuring arthralgia severity in multiple joint locations. The PRAI consists of 16 items that query pain severity over the last 7 days in eight joint pair groups: bilateral (left and right as two separate sets of items) fingers, wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees, ankles, and toes. The questionnaire uses a rating scale of 0–10, with 10 being greatest severity (Table S1). We scored the PRAI by first calculating the sum of responses across all joints, ranging from 0 to 160. For ease of interpretation, the average severity of pain per joint (0–10) was then calculated by dividing the total score by the number of items answered.

Data on several related constructs were collected concomitantly with the PRAI. Comorbidities were assessed using a checklist. For the analyses we categorized comorbidities as joint-related (osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, lupus, gout, ankylosing spondylitis, fibromyalgia, osteoporosis, osteopenia, or Sjogren’s syndrome) or not joint-related (diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Parkinson’s disease, renal failure, urinary tract problems, gastrointestinal problems, anemia, eye problems, or no other comorbidity). We assessed physical function and pain interference using the previously validated Patient-Reported Measurement Information System (PROMIS) scales.Citation30,Citation31 PROMIS physical function and pain interference scores were standardized according to the PROMIS instructions. We measured performance status using a patient-reported adaptation of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status measure.Citation32 The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Endocrine Subscale (FACT-ES) was administered to measure menopausal symptom severity.Citation33 The last item of the FACT-ES instrument is “I have pain in my joints”, with the following response options: “None,” “A little bit,” “Somewhat,” “Quite a bit,” and “Very much.” This item about arthralgia was added to the FACT-ES as a result of the findings regarding secondary effects of the AI anastrozole in the Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination trial.Citation34,Citation35

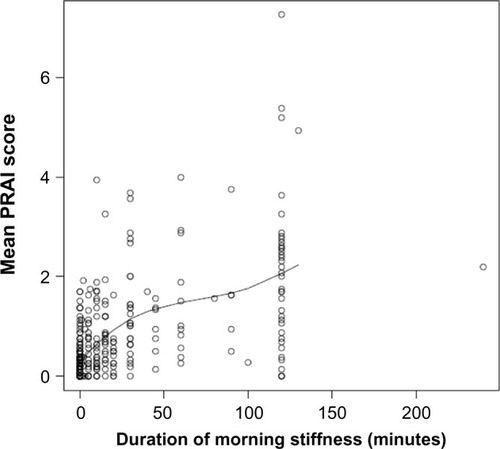

As a patient-reported proxy for the presence of inflammation,Citation36 we collected information regarding the duration of morning stiffness in minutes. Respondents who answered “yes” to the question “Over the past 7 days, have you had overall morning stiffness in your muscles or joints?” were asked how many minutes the morning stiffness had lasted. A check box was available to indicate if the morning stiffness had lasted more than 120 minutes. If a value for duration was entered and the “more than 120 minutes” box checked, we used the reported value.

Statistical methods

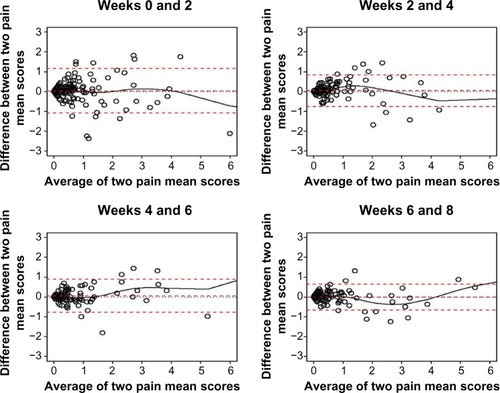

To assess the reliability of the PRAI, we calculated its internal consistency via Cronbach’s alpha for the overall score and for the score with each item removed. Additionally, we assessed test-retest reliability in the comparison group, in which minimal change would be expected, by examining the change in scores assessed at 2-week intervals (weeks 0 and 2, weeks 2 and 4, and so on). For each set of biweekly measurements, we computed a Spearman correlation coefficient with a 95% confidence interval (CI) to assess the strength of associations, and generated Bland-Altman plots to evaluate agreement. We also computed the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and corresponding CIs.

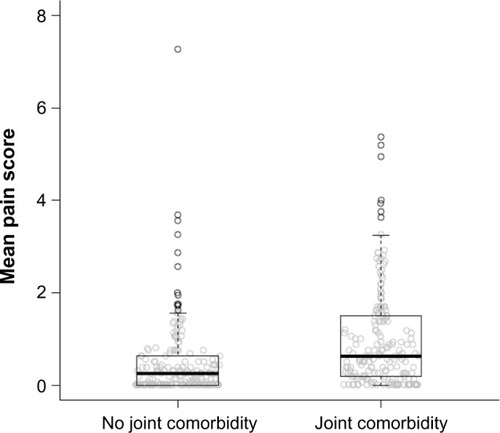

To examine the construct validity of the PRAI, we assessed both known-groups validity and convergent validity. Known-groups validity was addressed by: comparing PRAI scores of AI patients with those of comparison group subjects at baseline and over time; and comparing PRAI scores of patients with joint comorbidities with those without joint comorbidities at baseline. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests and box-plots were used to assess differences in groups for each of the above comparisons. We assessed concurrent validity by comparing PRAI scores at baseline and at follow-up with scores from the single FACT-ES question reporting pain in joints. To assess convergent validity, we examined whether PRAI scores correlated with other validated measures, including the PROMIS physical function, PROMIS pain interference, and ECOG performance status. Spearman correlation coefficients and CIs were used to evaluate these associations.

To better understand the relationship between morning stiffness and arthralgia, we examined the association of PRAI scores with patient-reported duration of morning stiffness using Spearman correlation coefficients, Bland-Altman plots, and ICCs. CIs for Spearman correlation coefficients were obtained using percentiles of bootstrap samples.

Results

Data from 330 women were included in the final analysis (). A detailed breakdown of population characteristics, univariate descriptive characteristics, and univariate comparisons by group can be found in Castel et al.Citation5 The individual PRAI items were all highly positively skewed; the median value for all items was zero. Respondents reported the lowest arthralgia severity in the elbows and higher arthralgia severity in the knees, hips, and shoulders. Cronbach’s alpha for the PRAI pain severity items was estimated to be 0.90. None of the alpha values based on individual item removal were greater than the total alpha, indicating that no item was negatively affecting the scale’s internal consistency reliability.

Test-retest reliability is reported in the form of ICC coefficients, which were calculated within subjects in the comparison group using PRAI assessments collected 2 weeks apart (). ICC values ranged from 0.87 to 0.96 for the repeated assessments. The corresponding Spearman correlation coefficient estimates also indicate fairly strong associations (range: 0.71–0.86). The Bland-Altman plots in show levels of agreement between assessments taken 2 weeks apart. There is strong overall agreement, with less agreement between weeks 0 and 2 than at subsequent time points.

Figure 2 Test-retest reliability. Bland-Altman plot of agreement between Patient-Reported Arthralgia Inventory assessments taken 2 weeks apart, with smoothed curve.

Table 1 Estimated ICC and Spearman ρ for PRAI scores for one patient taken 2 weeks apart

With regard to validity, shows boxplots of baseline PRAI scores for those participants with and without joint comorbidities. The estimated difference in mean scores between groups was −0.3 (CI −0.5, −0.2; P<0.001). As expected, women with joint comorbidities tended to have higher arthralgia severity scores than those without joint comorbidities. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test of the null hypothesis that both groups had the same distribution of scores was highly significant (P<0.001), suggesting known-groups validity with respect to joint comorbidity.

Figure 3 Baseline mean Patient-Reported Arthralgia Inventory scores by presence of joint comorbidity.

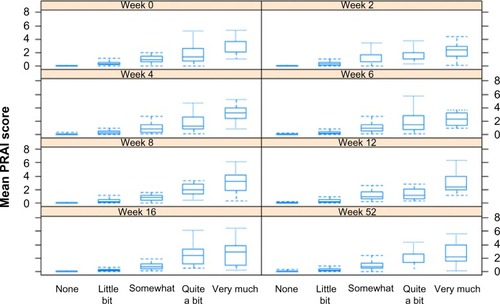

shows boxplots of the PRAI scores in relation to different levels of response to the FACT-ES item “I have pain in my joints” separately by week. The PRAI scores increase with higher FACT-ES ratings, further indicating known-groups validity. lists the Spearman correlation estimates between the two measures over time, which show high associations (range: 0.76–0.82). This supports the concurrent validity of the PRAI.

Figure 4 Mean PRAI score by response to the FACT-ES item “I have pain in my joints” over time.

Table 2 Estimated Spearman correlation between mean PRAI score and FACT-ES item “I have pain in my joints” by week

We assessed convergent validity by examining the relationship between the mean PRAI scores and each of the PROMIS physical function T scores, PROMIS pain interference T scores, and ECOG performance status. PRAI scores tended to be lower among those with better physical function scores (estimated Spearman correlation coefficient: −0.47, 95% CI −0.55, −0.37; P<0.001). PRAI scores were higher among those with higher PROMIS pain interference (estimated Spearman correlation coefficient: 0.65, 95% CI 0.57–0.72; P<0.001). ECOG performance status that was not fully active was associated with higher PRAI scores (estimated difference in location scores: −0.6, 95% CI −0.9, −0.4; P<0.001).

shows a plot of the duration of morning stiffness in minutes and PRAI scores at baseline. The Spearman correlation between these measures was 0.62 (95% CI 0.54–0.69; P<0.0001), indicating greater morning stiffness among those women with higher PRAI scores.

Discussion

Since the discovery of arthralgia as a secondary effect of AIs, there has been a need for a validated multi-item arthralgia measurement instrument. Our overall objective was to understand the psychometric properties of the PRAI. Our findings can be interpreted in the context of established thresholds for strength of association. For Cronbach’s alpha,Citation37 a threshold value of 0.70 indicates good internal consistency;Citation38 we observed very high internal consistency reliability (0.90) among the PRAI pain severity items. Similarly, 0.70 is a criterion for adequate test-retest reliability.Citation39 The PRAI’s high ICC values (range: 0.87–0.96) indicate that the variation in scores at each 2-week interval is almost exclusively due to differences between patients, rather than variability within patients.

We observed that despite the PRAI’s strong overall test-retest reliability, with all coefficients exceeding 0.70, arthralgia severity was reported higher at baseline than at any subsequent assessment. This resulted in less agreement between scores at weeks 0 and 2 than those at later weeks among the women without breast cancer. Mishra and Kuh similarly observed greater patient-reported menopausal symptom severity upon first assessment as compared with subsequent assessments in a general population, excluding the baseline data from their results for this reason.Citation2 In the absence of a feasible biological explanation for why symptom severity might be greater at baseline than at later assessments, future research should examine a potential pattern of greater severity the first time a symptom severity question is asked.

Our findings confirmed expectations based on past research that greater arthralgia severity as reflected by higher PRAI scores was associated with increased severity/impact of other symptoms of post menopause, aging, and illness in general as reflected by other patient-reported outcomes measures. Specifically, we observed concomitant decline in physical function, increased interference of pain with activities of daily living, reduced performance status, and increased morning stiffness among the patients with greater PRAI-measured arthralgia severity. Our finding regarding increased morning stiffness as a proxy for inflammation suggests that patients experiencing more severe arthralgia were more likely to present with patient-reported symptoms of inflammation. Further research should explore, perhaps by administering the PRAI concurrently with biomarker collection and/or rheumatology examination (including range of motion assessment), the role of arthralgia in inflammation and vice versa, so that diagnostic methods, treatments, and/or symptom-dependent decisions regarding AI therapy may be more informatively developed for and discussed with patients.

The PRAI fulfills an important clinical research need for a multi-item scale, the benefits of which for measurement are described by Nunnally and Bernstein.Citation38 Because the PRAI was developed in collaboration with patients and with experts in rheumatology, it also has good face and content validity. Our previous work with this scale also lends evidence to support its construct validity. The model-based trajectory of PRAI scores in women initiating AI therapy at baseline diverged at week 6 from the trajectory of postmenopausal women without cancer (P<0.01). The trajectories also showed an increase in arthralgia severity among those taking AI therapy over the 52 weeks of per-participant observation.Citation5

Our findings indicate that this instrument has satisfactory reliability and validity for use in assessing the severity of arthralgia in clinical and nonclinical/general populations. Our key results indicate strong internal consistency and test-retest reliability of the PRAI, and provide evidence of its construct validity using a multi-method approach.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge members of the study team, ie, Tonya Brown, Jessica Islam, Danielle LaMorte, Ashley Pasquariello, Angel Sherrill, and Angela Zito. We are also grateful for programming support from Joseph Burden, Gregory Todd Salter, Mikhail Zemmel, and Joseph Schneider, and contributions to screening provided by the Vanderbilt Cancer Trials Information Program. Dr Castel would like to thank her mentor Dr Katherine Hartmann. We thank two rheumatologists: Dr Fred Wolfe of the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases, and Dr Chad Boomershine of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, who provided expert input and helped develop the measure. This study was funded by the American Cancer Society (119475-MRSG-10-169-01-PCSM, Dr Liana Castel, principal investigator [PI]), Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UL1RR024975-01 and UL1TR000011 from the National Institutes of Health, Dr Liana Castel, PI), and 5K12HD43483-10 (Dr Katherine Hartmann, PI) from the National Institutes of Health Building Interdisciplinary Careers in Women’s Health Research.

Supplementary materials

Table S1 Patient-Reported Arthralgia Inventory

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CunninghamLSKelseyJLEpidemiology of musculoskeletal impairments and associated disabilityAm J Public Health1984745745796232862

- MishraGDKuhDHealth symptoms during midlife in relation to menopausal transition: British prospective cohort studyBMJ2012344e40222318435

- BursteinHJAromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgia syndromeBreast20071622323417368903

- BuzdarAUATAC Trialists GroupClinical features of joint symptoms observed in the ‘Arimidex’, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) trial Available from: http://meeting.ascopubs.org/cgi/content/short/24/18_suppl/551Accessed May 20, 2015

- CastelLDHartmannKEMayerIATime course of arthralgia among women initiating aromatase inhibitor therapy and a postmenopausal comparison group in a prospective cohortCancer20131192375238223575918

- CellaDFallowfieldLJRecognition and management of treatment-related side effects for breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapyBreast Cancer Res Treat200810716718017876703

- BellamyNBuchananWWGoldsmithCHCampbellJStittLWValidation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or kneeJ Rheumatol198815183318403068365

- BremanderABPeterssonIFRoosEMValidation of the Rheumatoid and Arthritis Outcome Score (RAOS) for the lower extremityHealth Qual Life Outcomes200315514613567

- DoyleDVDieppePAScottJHuskissonECAn articular index for the assessment of osteoarthritisAnn Rheum Dis19814075787008713

- HawkerGADavisAMFrenchMRDevelopment and preliminary psychometric testing of a new OA pain measure – an OARSI/OMERACT initiativeOsteoarthritis Cartilage20081640941418381179

- MasonJHAndersonJJMeenanRFHaralsonKMLewis-StevensDKaineJLThe Rapid Assessment of Disease Activity in Rheumatology (RADAR) questionnaire. Validity and sensitivity to change of a patient self-report measure of joint count and clinical statusArthritis Rheum1992351561621734905

- RenXSKazisLMeenanRFShort-form Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales 2: tests of reliability and validity among patients with osteoarthritisArthritis Care Res19991216317110513506

- RitchieDMBoyleJAMcInnesJMClinical studies with an articular index for the assessment of joint tenderness in patients with rheumatoid arthritisQ J Med1968373934064877784

- StuckiGLiangMHStuckiSBruhlmannPMichelBAA self-administered Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index (RADAI) for epidemiologic research. Psychometric properties and correlation with parameters of disease activityArthritis Rheum1995387957987779122

- WelsingPMvan GestelAMSwinkelsHLKiemeneyLAvan RielPLThe relationship between disease activity, joint destruction, and functional capacity over the course of rheumatoid arthritisArthritis Rheum2001442009201711592361

- van der HeijdeDMvan ‘tHMvan RielPLvan de PutteLBDevelopment of a disease activity score based on judgment in clinical practice by rheumatologistsJ Rheumatol1993205795818478878

- BartonJLCriswellLAKaiserRChenYHSchillingerDSystematic review and metaanalysis of patient self-report versus trained assessor joint counts in rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol2009362635264119918045

- MoralesLPansSParidaensRDebilitating musculoskeletal pain and stiffness with letrozole and exemestane: associated tenosynovial changes on magnetic resonance imagingBreast Cancer Res Treat2007104879117061044

- MoralesLPansSVerschuerenKProspective study to assess short-term intra-articular and tenosynovial changes in the aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgia syndromeJ Clin Oncol2008263147315218474874

- SavnikAMalmskovHThomsenHSMagnetic resonance imaging of the wrist and finger joints in patients with inflammatory joint diseasesJ Rheumatol2001282193220011669155

- DizdarOOzcakarLMalasFUSonographic and electrodiagnostic evaluations in patients with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgiaJ Clin Oncol2009274955496019752344

- TaalEAbdel-NasserAMRaskerJJWiegmanOA self-report Thompson articular index: what does it measure?Clin Rheumatol1998171251299641509

- O’MalleyKJSuarez-AlmazorMAniolJJoint-specific multidimensional assessment of pain (J-MAP): factor structure, reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients with knee osteoarthritisJ Rheumatol20033053454312610814

- WolfeFPain extent and diagnosis: development and validation of the regional pain scale in 12,799 patients with rheumatic diseaseJ Rheumatol20033036937812563698

- JensenMPTurnerJARomanoJMFisherLDComparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measuresPain19998315716210534586

- HadjiPImproving compliance and persistence to adjuvant tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitor therapyCrit Rev Oncol Hematol20107315616619299162

- US Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; US Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research; US Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological HealthGuidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidanceHealth Qual Life Outcomes200647917034633

- HarrisPATaylorRThielkeRPayneJGonzalezNCondeJGResearch Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics supportJ Biomed Inform20094237738118929686

- BaschEArtzDDulkoDPatient online self-reporting of toxicity symptoms during chemotherapyJ Clin Oncol2005233552356115908666

- AmtmannDCookKFJensenMPDevelopment of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interferencePain201015017318220554116

- RoseMBjornerJBBeckerJFriesJFWareJEEvaluation of a preliminary physical function item bank supported the expected advantages of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)J Clin Epidemiol200861173318083459

- BaschEIasonosABarzALong-term toxicity monitoring via electronic patient-reported outcomes in patients receiving chemotherapyJ Clin Oncol2007255374538018048818

- FallowfieldLJLeaitySKHowellABensonSCellaDAssessment of quality of life in women undergoing hormonal therapy for breast cancer: validation of an endocrine symptom subscale for the FACT-BBreast Cancer Res Treat19995518919910481946

- BaumMBuzdarACuzickJAnastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination) trial efficacy and safety update analysesCancer2003981802181014584060

- CellaDFallowfieldLBarkerPCuzickJLockerGHowellAQuality of life of postmenopausal women in the ATAC (“Arimidex”, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years’ adjuvant treatment for early breast cancerBreast Cancer Res Treat200610027328416944295

- RudwaleitMMetterAListingJSieperJBraunJInflammatory back pain in ankylosing spondylitis: a reassessment of the clinical history for application as classification and diagnostic criteriaArthritis Rheum20065456957816447233

- CronbachLJCoefficient alpha and the internal structure of testsPsychometrika195116297334

- NunnallyJCBernsteinIHPsychometric Theory3rd edNew York, NY, USAMcGraw-Hill1994

- TerweeCBBotSDde BoerMRQuality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnairesJ Clin Epidemiol200760344217161752