Abstract

Psychotic spectrum disorders are serious illnesses with symptoms that significantly impact functioning and quality of life. An accumulating body of literature has demonstrated that specialized treatments that are offered early after symptom onset are disproportionately more effective in managing symptoms and improving outcomes than when these same treatments are provided later in the course of illness. Specialized, multicomponent treatment packages are of particular importance, which are comprised of services offered as soon as possible after the onset of psychosis with the goal of addressing multiple care needs within a single care setting. As specialized programs continue to develop worldwide, it is crucial to consider how to increase access to such specialized services. In the current review, we utilize an ecological model of understanding barriers to care, with emphasis on understanding how individuals with first-episode psychosis interact with and are influenced by a variety of systemic factors that impact help-seeking behaviors and engagement with treatment. Future work in this area will be important in understanding how to most effectively design and implement specialized care for individuals early in the course of a psychotic disorder.

Psychosis and treatment: an overview

Psychotic spectrum disorders, which include schizophrenia spectrum disorders and mood disorders with psychotic features, are pervasive and serious illnesses. Under usual systems of care, the course of these illnesses is characterized by repeated symptomatic relapses,Citation1 numerous comorbidities (eg, anxiety, depressive episodes, substance use),Citation2 and an average life span that is reduced by up to 25 years.Citation3 Relative to their prevalence, the economic burden of these illnesses is disproportionately high. For example, despite affecting only 0.3%–1.6% of the US population,Citation4 the estimated cost of one commonly diagnosed psychotic spectrum disorder (ie, schizophrenia) in the USA during 2013 was $155.7 billion.Citation5

Research strongly suggests that the first few years following the onset of psychotic symptoms represents a critical period for intervention.Citation3 More specifically, this is when 1) the majority of the decline in health and functioning unfoldsCitation6 and 2) individuals with psychosis experience the greatest therapeutic response to existing pharmacological and psychosocial treatments.Citation7,Citation8 These findings have, in part, sparked the rapid international expansion of specialty multicomponent treatment programs for individuals with first-episode psychosis (FEP). This treatment approach – referred to within the USA as “Coordinated Specialty Care” and recognized internationally as specialized care for FEP – has been shown to produce improvements in symptomatology and functional outcomes among individuals with FEPCitation9 that may exceed those experienced under usual care.Citation10,Citation11

Unfortunately, many individuals with FEP experience a prolonged delay between the first onset of frank psychotic symptoms and receipt of adequate mental health careCitation12 – a period of time referred to as the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP). Given strong evidence indicating that longer DUP is associated with negative clinical outcomes and worse response to treatment among individuals with FEP,Citation10,Citation13,Citation14 DUP has been identified as an important modifiable risk factor for improving the course of psychotic disorders.Citation15,Citation16 With some notable exceptions,Citation17,Citation18 attempts to reduce DUP and to increase access to specialized care programs for individuals with FEP have been largely unsuccessful.Citation19 Given the complexity of factors contributing to DUP and the variation of these factors across different healthcare environments, there is likely no singular approach to reducing DUP that can be effectively implemented across settings.Citation20,Citation21 Consequently, there is a need for the development of accurate heuristics to guide the identification of the unique factors that influence access to specialized services among individuals with FEP within specific communities.Citation12,Citation22

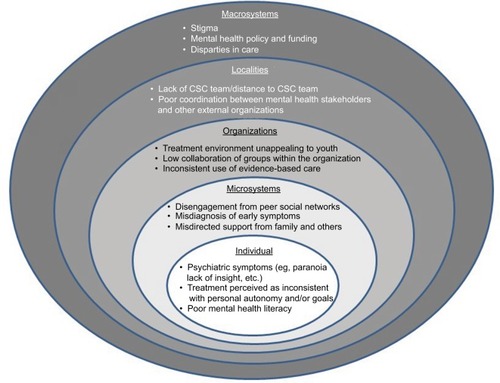

In this manuscript, we will review the working model of factors influencing access to specialized services for FEP developed at a specialized care clinic (the Ohio State University-Early Psychosis Intervention Center [OSU-EPICENTER]), as guided by existing theoretical models of social ecology and human development. This working model considers efforts to improve access to specialized care as “multilevel interventions.”Citation23 Growing data suggest that health interventions that simultaneously target factors at multiple levels of the ecological context in which the health concern exists (eg, individual level, organizational level, population level) are more effective than interventions that target only a single level.Citation24 Drawing on the ecological levels of analysis modelCitation25 as a guiding framework – which, in turn, is guided by Bronfenbrenner’s seminal ecological theory of human developmentCitation26 – our working model focuses on five nested interdependent levels of factors hypothesized to influence access to care: 1) individuals; 2) microsystems; 3) organizations; 4) localities; and 5) macrosystems – see . Below, we highlight examples of factors at each level of analysis that may influence access to specialized care for FEP. However, given local variation in factors influencing access to care across different settings, we advocate for the development of community-based models in which community stakeholders shape the identification of the specific multilevel factors influencing access to care in their community as well as the proposed solutions to these problems.Citation23 Consequently, when applied to a specific community, this working model should serve only a heuristic to guide discussion and identification of the specific factors influencing access to care within that locale.

Multilevel factors influencing access to specialized care

Individuals

Individual factors influencing human behavior range from biological factors (eg, genetics, neuroanatomy) to psychological factors (eg, self-efficacy, cognition) to social factors (eg, perceived social support). Numerous individual factors influence access to specialized care among individuals with FEP, including the severity of psychiatric symptoms and mental health literacy.

Various psychiatric factors have the potential to delay access to care for individuals with FEP. Paranoid thinking and persecutory delusions can interfere with an individual’s willingness to seek help. Moreover, psychiatric comorbidities commonly experienced by individuals with FEP (eg, anxiety, depression) may also interfere with help-seeking via increased attention to potential sources of threat (eg, social rejection, stigma concerns), higher levels of shame around illness, and the use of less effective emotion regulation strategies such as avoidance and suppression.Citation27–Citation29 Lack of insight into illness or minimization of symptoms may further hinder help-seeking behavior.Citation30,Citation31

Deficits in mental health literacy and negative perceptions of mental health care are additional individual-level barriers to care. Mental health literacy – the ability to recognize mental health problems, to understand causes and risks, and to seek appropriate consultation or treatmentCitation32 – can contribute to a failure to seek professional help via a generalized lack of awareness around mental health and illness. Evidence suggests that young people are reluctant to seek care for mental health problems,Citation33 possibly due in part to the onset of symptoms occurring during a period marked by still-developing knowledge and experience.Citation32 Young people are also more likely to erroneously believe that they should be able to deal with their mental health symptoms on their own.Citation33 When young people do experience distress in response to psychological symptoms, they are prone to use labels such as “stress” or “life problem” that are intended to normalize, yet are less likely to facilitate help-seeking behavior.Citation32 Self-stigma around mental illness may underlie this pattern of behavior,Citation22 as the prospect of acknowledging mental illness in oneself can lead to significant reductions in self-esteem.Citation34 Finally, negative perceptions with regard to mental health treatment may further hinder help-seeking. Studies indicate that as many as one third of individuals with FEP report a lack of interest in receiving treatment,Citation30 and they may also feel overwhelmed by the process of initiating care, or that there are “too many steps” that need to be navigated.Citation22 Individuals with FEP may also be hesitant to seek care if they perceive its focus as only the management of psychiatric symptoms or otherwise inconsistent with their personal goals (eg, a young adult with psychosis may be interested in getting a job, but less so in addressing hallucinations or delusions).

Addressing barriers to care at the individual level involves the consideration of developmentally informed and personalized interventions that are maximally attractive to young people with FEP. As psychotic disorders generally manifest in the late teenage or early adult years,Citation35 considering the unique needs of this developmental stage is crucial in optimizing our approaches to engaging youth in care. ArnettCitation36 has described this developmental period as “emerging adulthood,” a stage of life marked by identity exploration in the domains of work and relationships with the goal of becoming self-sufficient. Thus, one possible approach to address individual-level barriers is the provision of care that embraces these developmental needs by focusing on the areas of skill development relevant to obtaining these milestones (eg, supported employment and education and strategies for forming and maintaining relationships) in addition to psychoeducation to address mental health literacy and skills for coping with psychiatric symptoms. This approach is consistent with information obtained via studies of qualitative interviews with youth with psychosis, which suggests that programs should emphasize all aspects of the program as not to dissuade those reluctant to have only “psychiatric” treatment (ie, psychosocial elements should be discussed along with pharmacological and physician aspects).Citation22 In addition, utilizing a flexible, person-oriented approach to facilitating motivation for treatment is paramount in fostering engagement with care. Given that a variety of presenting psychiatric symptoms may interfere with building trust and willingness to proceed with treatment (lack of insight, motivational deficits, and/or paranoid thinking styles), striving to immediately establish a healthy alliance as soon as individuals seek care and forming collaborative client-centered goals are imperative.

Microsystems

Microsystems are the immediate environments in which individuals engage in direct, personal interactions over time.Citation25 Microsystems are diverse and unique to each individual, but generally include interactions with one’s immediate family, peers, and other settings of daily living activities. Among individuals with FEP, examples of microsystem factors that may hinder access to care include disengagement from peer networks, misguided support from family and others, and misdiagnosis of early symptoms.

Psychotic disorders are marked by impairments in social functioning that are present even before the full onset of positive symptomsCitation37 and contribute to a deterioration of relationships early in the illness.Citation38 Disengagement from peer networks may impede access to care via reduced likelihood of others who know the individual well noticing and communicating about concerning changes in behavior and also in increasing the risk for the individual with FEP to encounter social stressors that exacerbate psychiatric symptoms or increase reticence to ask others for help (ie, bullying, rejection, and hostility from peers).Citation39,Citation40

In addition, the early signs and symptoms of FEP may be missed or even misinterpreted by others in the immediate environment of the individual. Many of the early signs of psychosis – changes in social behavior, school misconduct, and inconsistent interest in previously enjoyed activities – may be difficult for family members to disentangle from more normative shifts and changes associated with teenage and young adult behavior.Citation41 Further, the stigma of mental illness may lead some families to be reluctant to recommend mental health treatment to their relative with psychosis – at times in an effort to avoid diagnoses that may confer negative responses from others.Citation42 It is important to note that such occurrences are not limited solely to familial caregivers – similar patterns of vulnerability to misdiagnosis and lack of appropriate support are also observed among professional providers. For example, research in population-based samples suggests that frontline healthcare providers also evidence a delayed recognition of the early signs of the illness or may make misguided attempts to manage the psychotic symptoms without additional referral.Citation43

Addressing microsystem barriers to the receipt of specialized care for individuals with FEP involves, in many cases, providing education and support to activate and engage the potential of important relationships in the individual’s life to facilitate connection with appropriate care. As the relationships at this level are characterized by frequent interactions over periods of time (ie, families, peers, and providers of general health care), their potential to support and direct individuals with FEP to appropriate care is paramount. A potential strategy for addressing barriers at this level may be offering support services to families themselves. These services are conducive to creating supportive relationships of family members to the individual with FEP and also provide an important venue for concerned family members to receive information from care providers and other families facing similar struggles. Further, research shows that when individuals with FEP do not themselves engage with appropriate treatment, relatives often play a crucial role in connecting them to care.Citation30,Citation44 Thus, providing this type of support may improve rates of accessing specialized care for FEP. Possible specialized forms of family education and support include multifamily group psychoeducationCitation45 – a clinically beneficial and cost-effective formatCitation46 that involves multiple families offering and receiving support to one another. Providing opportunities for engagement with peers may also increase willingness to engage with specialized care, and youth with FEP note desires for peer contact as part of their treatment (ie, opportunities to interact with other young adults receiving similar care).Citation22 To foster peer engagement, specialized treatment programs may offer group interventions or provide peer-mentoring opportunities. Individuals with FEP also request interventions aimed at increasing social resilience and providing skills for establishing and maintaining healthy relationships.Citation47 Finally, efforts to provide education and resources to frontline healthcare providers have potential to reduce delayed recognition or misdiagnosis of early signs of psychosis (see “Localities” section).

Organizations

The organizations level refers to the associations or consortiums that encompass the collection of microsystems with which the individual interacts (eg, clinics, human service organizations, schools)Citation25 – including organizations that provide treatment for FEP. Possible examples of barriers to care at this level include factors related to the organization and provision of care, including treatment environments that are unappealing to youth, inconsistent availability of evidence-based practices, and low levels of collaboration within microsystems of the organization.

The environment of FEP programs can impact the willingness of young adults to establish and maintain care. In particular, certain settings of care may operate with designs that are unappealing to youth with FEP. For example, young adults receiving care for FEP have noted that characteristics common to many mental health settings (long waits in austere waiting rooms full of strangers and meeting with different providers who have limited communication and thus needing to recount personal details many times at different appointments before receiving care)Citation22 negatively impact desire to receive care. Some youth find these typical settings stigmatizing or incongruent with their developmental and cultural needs,Citation48 which may further influence the avoidance of seeking specialized care for FEP. Taken together, these findings highlight the need to consider ways to create treatment environments that are “youth-friendly” and thus conducive to accessing and engaging with services.

In addition, the availability of evidence-based treatments within organizations providing care for FEP is variable. Although numerous trials of evidence-based, multicomponent care for FEP have demonstrated significant benefit from this type of treatment,Citation11,Citation50 there is a notable interprogram variability in the specific types of interventions that are actually offeredCitation51 – meaning that not all services providing care for FEP are utilizing treatment approaches that are most supported by research. Programs also differ in their assessment of fidelity to treatment, and thus, the degree to which evidence-based practices are implemented and followed is difficult to ascertain. Further, many specialized care programs do not routinely monitor the outcomes of individuals participating in their services. In fact, among the numerous specialized treatment programs within the USA, only five organizations/networks have published data demonstrating the benefits of their clinical programs.Citation10,Citation12,Citation49,Citation51,Citation52 Completing specialized training in evidence-based interventions for FEP and building routine outcomes assessment into services may present several challenges to programs providing care for FEP (eg, accessing training in evidence-based practices for FEP, turnover among trained staff, limited experience with implementing outcomes assessment). However, collaborations with academic partners with expertise in specialized care for FEP may provide crucial support in the process of effectuating this type of system (see “Localities” section).

Although the evidence suggests that specialized care for FEP has a clear clinical benefit, functional outcomes for many individuals receiving care from these programs remain suboptimal.Citation16 One avenue for optimizing access to care at the organizational level is to increase the initiation of care by creating a “youth-friendly” environment. Recently, additional attention has been given to the creation of mental health services that are sensitive to the developmental and cultural needs of young people in order to improve service utilization.Citation53 This approach – which is apparent in the design of broad, specialized youth mental health program outside of the USA (ie, headspace in Australia and Jigsaw in Ireland)Citation54 – is focused on responsive, hope-oriented delivery of care in a stigma-free, youth-engaging location that is easily accessible via public transportation. More recently, in the USA, the Institute for Mental Health Research (IMHR)-EPICENTERCitation55 in Phoenix, AZ, USA, utilized youth-friendly considerations in selecting the location and designing the clinical spaces to promote engagement with care. This process involved selecting a centrally located building that is easily accessible via public transportation and within walking distance to other sites of interest to young adults (eg, coffee shops, libraries, educational organizations). The interior of the selected building was also designed to create an inviting, nonstigmatizing youth environment that would be conducive to prolonged periods of “hanging out” with other youth receiving care (ie, televisions, computers with Internet access, video game consoles, ample spread-out seating). The outside, street-facing wall of the IMHR-EPICENTER clinic features a recovery-oriented mural that depicts youth in valued social roles and was painted by a local psychosocial rehabilitation group of individuals with lived experience of mental illness.Citation56

Finally, the way that each treatment program creates intraorganizational relationships will impact access to care for individuals with FEP. The microsystems within each organization are likely to vary (eg, a hospital-based first-episode program will likely have a psychiatric inpatient unit, while most community mental health centers will not), but even smaller organizations will likely have multiple focuses or “care teams” within the same setting. However, routine communication between clinical teams is not necessarily standard, nor are routes for collaboration always easily accessible. Although some young adults with psychosis do access care directly via specialized first-episode programs, many others will make treatment contact via other institutional inroads (ie, inpatient units or primary care)Citation12 – and without frequent communication and collaboration, these young adults may not reach the specialized care they need. Thus, creating ongoing collaboration between clinical services and teams within organizations providing treatment to youth with FEP is another potential avenue for optimizing access to specialized care. Successful approaches will vary based on the individual characteristics of each organization, with common goals of streamlining referral of eligible individuals to specialized FEP treatment as well as providing appropriate integrated consultation and care for the needs of individuals with FEP across specialties (eg, a young adult with FEP receiving specialized care may benefit from meeting with a primary care physician outside of the team to address physical health comorbidities). Organizations with inpatient units represent a particularly relevant opportunity for collaboration, as many youth with FEP have their first treatment contact in this setting.Citation57 Although studies have suggested that individuals with psychosis can benefit from evidence-based psychosocial interventions in the inpatient setting,Citation58 almost all specialized interventions are available only on an outpatient basis. Although it may not be prudent to implement an entire specialized FEP treatment program in the inpatient setting, integrating elements of care can reduce the delay of specialized care in a way that may facilitate greater likelihood to connect with specialized care following discharge.

Localities

The localities level describes a system of organizations and their constituent microsystems, typically within an identifiable geographic locality.Citation25 In terms of optimizing access to high-quality care for individuals with FEP, examples of potential barriers include lack of a proximal specialized care teams providing evidence-based care and poor coordination between mental health stakeholders and other relevant organizations in the community.

Improved availability of specialized care for FEP is a well-recognized need in the treatment community. Further, research has shown that for each additional mile of distance between an individual’s home and specialized care clinic, that individual’s respective DUP increases by 1 monthCitation59 – thus highlighting the importance that services are available in proximity to each individual’s community. Thus, one of the greatest accomplishments of the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode Early Treatment Programs (RAISE ETP) trialCitation10 may have been the demonstration that evidence-based practices for FEP can successfully be disseminated within the USA community mental health system.Citation50 However, the mental health literature is replete with examples of dissemination projects in which the benefits of evidence-based practices drop precipitously, and may disappear entirely, when transferred from laboratory settings to community settingsCitation60,Citation61 – a phenomenon known as the “implementation cliff.”Citation62

To address this concern, many developing community specialized care programs have partnered with one of the five specialized FEP networks/programs with demonstrated clinical efficacy for technical assistance and support. Such community–academic partnerships have been shown to be effective in supporting the dissemination and sustainability of evidence-based practices in community settings.Citation63,Citation64 Yet, literature on effective models of technical assistance is scant.Citation65 Consequently, below we provide a brief overview of the technical assistance model used by one specialized care program – EPICENTERCitation52 – in assisting community agencies to launch new FEP programs. Although this model is only one example and is a developing model, it may serve as a useful foundation for agencies interested in delivering or receiving technical assistance with regard to specialized care for FEP within their respective settings.

The technical assistance model implemented by EPICENTER is guided by self-determination theory,Citation66 which postulates that human motivation and well-being are enhanced via satisfaction of three basic psychological needs: autonomy (ie, choice and volitional control with regard to one’s actions), competence (ie, perceived effectiveness in one’s activities), and relatedness (ie, feeling connected to others in one’s community). Within organization settings, satisfaction of these basic needs has been shown to improve employee job satisfaction and performance, to increase acceptance of organizational change, and to facilitate greater motivation to implement new work practicesCitation67 – factors that may be critical in implementing a new evidence-based practice, such as specialized care for FEP, in a community mental health center.Citation68,Citation69 summarizes the components of the technical assistance model and the basic psychological need(s) of the developing treatment teams they target.

Table 1 EPICENTER technical assistance model

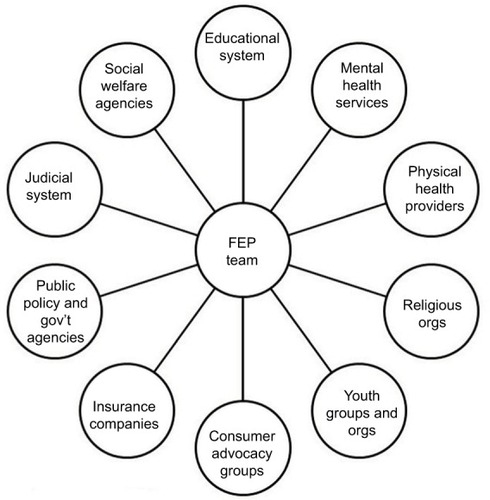

In sum, EPICENTER technical assistance efforts involve the provision of specialized training in evidence-based practices for FEP and ongoing consultation for treatment implementation that is mindful of the shared vision for each organization. In addition, EPICENTER assists organizations in forging connections within their broader communities. This approach, guided by procedures implemented at the Specialized Treatment Early in Psychosis,Citation12 involves targeted outreach to stakeholder groups that are impacted by and/or provides services to youth with FEP and their family members. shows these stakeholder groups with which FEP teams may endeavor to engage and collaborate. This outreach is crucial in improving awareness of the specialized care program to other organizations in the community and also providing specific instruction on referring youth with FEP and their families to services. Importantly, outreach to these stakeholders does not occur only once, but instead becomes an ongoing, regular pipeline for communication and referrals.

Figure 2 Community stakeholders.

Abbreviation: FEP, first-episode psychosis.

Ongoing collaborations with external organizations likely to interface with youth with FEP are also relevant in connecting individuals with FEP to care as early as possible. As studies have shown, the first point of contact for individuals with onset of psychosis is often a family physician or hospital emergency provider,Citation30 efforts have been made to provide education to healthcare providers to facilitate appropriate referrals to specialized services. Although some research has shown that targeted educational campaigns have potential to reduce delays in the receipt of care,Citation17 other studies have found that similar educational interventions do not result in a significant reduction in delay of referral to specialized care – even when an external specialized first-episode care program is readily available.Citation70 Of note, one study found that if the first treatment contact point for an individual with FEP is in the community mental health setting, the delay in the receipt of specialized intervention services was even longer than for those who presented initially to emergency or crisis services.Citation21 Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of not only expanding the availability of specialized treatment programs but also ensuring that these programs are integrated effectively into their larger communities and interface directly with other community organizations to tap into existing pathways of care.

Macrosystems

The final encompassing level of the ecological model is the macrosystems level, which is characterized by cultural forces, attitudes around change, and other factors that contribute to disparities in care.Citation25 As the outermost level, macrosystems create the context within which other levels operate and are influenced by society-level factors. Examples of factors that have potential to interfere with access to care for FEP at this level include stigma, mental health policy and funding, and disparities in approaches to care.

Stigma surrounding psychotic disorders – meaning the stereotypes and prejudices that result from misinformation and/or misunderstanding about mental illnessCitation34 – is of major concern in understanding barriers to treatment. Stigma surrounding schizophrenia and psychotic disorders often includes beliefs that people with these disorders are dangerous and unpredictable,Citation71 despite evidence suggesting any relationship is small and influenced by coexisting factors (ie, substance abuse).Citation72 Although stigma about mental illness is thought to be highly prevalent among the general public, stigmatizing views regarding mental illness are also present among mental health professionals.Citation34,Citation73 Psychosis is further stigmatized via representation in the media and popular culture, with people with psychotic illnesses often portrayed as violent and dangerous in modern horror films,Citation74 horror video games,Citation75 and even media intended for children (eg, cartoons).Citation76 Reviews of US newspapers from 2000 to 2010 found that it is not uncommon to use psychotic disorder diagnoses metaphorically in-print – eg, saying that “the weather will be schizophrenic” when it is thought to be unpredictable or dangerous.Citation77 As modern youth culture is marked by heavy media consumption in various formats,Citation78 these messages are particularly likely to influence perceptions about mental illness among youth with mental health concerns – including those with FEP. These messages have significant potential to be disempowering to youth with FEP – misconceptions about mental illness may lead individuals to believe that mental health concerns are their fault or that they are dangerous or otherwise unwanted in society. Thus, the prevalence of stigma may significantly reduce the likelihood that youth with FEP seek treatment by perpetuating beliefs that they are undesirable, solely responsible for the struggles and symptoms they are facing, or at risk of being given a diagnosis that would render them unable to integrate meaningfully into society. Research demonstrating that stigma interferes with help-seeking behavior among youth is consistent with this reasoning;Citation79 some individuals with psychosis note a desire to avoid a label of an illness which society perceives as negative as a barrier to connecting with services.Citation34 Surveys of individuals with psychosis further reveal that the majority of respondents indicate efforts to conceal their disorders due to significant worry that others may respond unfavorably.Citation80 At minimum, educational campaigns aimed at stigma reduction are warranted. The literature suggests that there is sufficient evidence for the development and rollout of educational programs aimed at reducing stigmatizing beliefs held by individuals.Citation81 The work done by López et alCitation82 to create La CLAve – a culturally minded psychoeducational program to improve mental health literacy among Spanish-speaking individuals in the western USA – is of particular relevance, which has demonstrated a beneficial impact on knowledge regarding symptoms, illness attributions, and willingness to seek help among community members.

The climate around mental health policy and funding also influences accessibility to care. Adequate financing is essential to implementing and maintaining services for individuals with FEP, and evidence suggests that dedicated funds for these services are the best predictor of success.Citation83 Following successful demonstration that specialized care for FEP is effective and can be disseminated into the community, legislation was passed by the US Federal Government providing states with a 5% increase in the Mental Health Block Grants provided by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in 2014 and 2015 to support the dissemination of specialized programs. This funding increased to a 10% in 2016 and has sparked an unprecedented dissemination of specialized care for FEP.Citation84 Despite expansion of funding for specialized care for FEP, many states continue to struggle with financial barriers to program implementation – including insufficient funds to cover operation costs and lack of reimbursement for some components of care.Citation50

Additional strategies include the utilization of funding mechanisms local to each program (eg, opportunities with local or regional mental health boards) and engaging tactics for covering services of uninsured individuals.Citation85 The need for continued innovation and creativity in financing specialized care for FEP is further highlighted by the uncertainty around healthcare accessibility and affordability. For example, federal legislation in the USA that has expanded accessibility and affordability of specialized FEP care (eg, the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion) has an uncertain future and may be disbanded or unfunded. At this time, however, it is certain that continued public support and funding of specialized FEP care will be crucial to its continued expansion and community proliferation.

Last, understanding treatment disparities for FEP is necessary in improving care. The way that physical health is addressed – or not addressed – is of particular relevance among people with psychotic disorders. Adults with psychotic disorders have a shortened life expectancy and are at an increased risk for a variety of physical health problems (eg, cardiovascular disease,Citation86 cancer,Citation87 and diabetes).Citation88 There are limited data for individuals with FEP, but 10-year follow-up data from Norway and Denmark have demonstrated 11-fold increases in all-cause mortality.Citation89 Data from the RAISE ETP studyCitation10 showed that first-episode individuals have higher rates of dyslipidemia and prehypertension when compared with age-matched controls.Citation86 Despite elevated rates of health problems and behavioral risk factors, there are significant disparities in how primary care is delivered to individuals with FEP. For example, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that individuals with schizophrenia were 31% less likely to be prescribed medications for chronic medical conditions compared with individuals without serious mental illnesses.Citation90 This is in line with findings that individuals with serious mental illness were 30% less likely to receive hospital care for cardiovascular disease or diabetes complications or receive blood glucose and lipid tests.Citation91 A more recent study has found that individuals with schizophrenia and coronary heart disease were approximately half as likely to be prescribed recommended medications compared with those without serious mental illness.Citation92 Given the disparities in behavioral risk factors and degree of primary care received, interventions need to be implemented for each individual and within the health system more broadly.Citation93 This approach could include focusing on increasing levels of physical activity and to achieving and maintaining a healthy weight. Although these interventions are not yet widespread, some have been developed for use with people with psychosis.Citation94 Health care–level interventions are also limited, with many aiming at increasing access to care or to health-screening services. We encourage continued development of these initiatives, with a possible future direction of use of algorithms to address prescription disparities. Medication algorithms, created from evidence-based guidelines, have been used to select initial antipsychotic medications for people with FEP.Citation95 However, these types of medication algorithms have not been used to initiate pharmacologic care for comorbid chronic medical conditions.

Conclusion

Given increased research and funding attention given to the treatment of psychotic disorders in their early stages, we have made significant gains in our ability to assist individuals living with these illnesses to recover and live full, meaningful lives. The development and dissemination of specialized care for FEP has been a crucial element of this progress; however, many opportunities for improving access to high-quality care remain. Looking forward, continuing to examine barriers within multiple levels of the ecological model is promising in identifying factors that may be amenable to modification. Navigating this process will require an additional effort to situate these programs effectively and advantageously in their respective communities and cultural contexts. Specifically, the inclusion of other community stakeholders and local knowledge in the development of specialized care programs for FEP has the potential to provide meaningful ideas and input on the specific aspects of content, process, and outcomes for designing a specialized FEP clinical team for a specific locale.Citation23 Finally, although we have made efforts to address factors that influence access to care across multiple levels, the current model is not considered definitive or exhaustive. Additional needs remain, including improving our understanding of how best to engage difficult-to-reach populations (eg, homeless individuals) and to address cultural needs across different locales and settings. Thus, the current model should only be considered as a heuristic for programs seeking to optimize access to care within their respective settings as well as a guide for future research examining additional factors influencing access to care among individuals with FEP.

Disclosure

Moe and Breitborde have received salary support from the IMHR to support the launch of IMHR’s new clinical service for individuals with FEP. They both have received salary support from the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services to support the launch of new clinical services for individuals with FEP in Fairfield County, OH, USA; Franklin County, OH, USA; and Athens County, OH, USA.

References

- MasonPHarrisonGGlazebrookCMedleyICroudaceTThe course of schizophrenia over 13 years. A report from the International Study on Schizophrenia (ISoS) coordinated by the World Health OrganizationBr J Psychiatry199616955805868932886

- BuckleyPFMillerBJLehrerDSCastleDJPsychiatric comorbidities and schizophreniaSchizophr Bull200935238340219011234

- BirchwoodMToddPJacksonCEarly intervention in psychosis. The critical period hypothesisBr J Psychiatry Suppl19981723353599764127

- KesslerRCBirnbaumHDemlerOThe prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Sample Replication (NCS-R)Biol Psychiatry200558866867616023620

- CloutierMAigbogunMSGuerinAThe economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2013J Clin Psychiatry201677676477127135986

- LiebermanJAPerkinsDBelgerAThe early stages of schizophrenia: speculations on pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approachesBiol Psychiatry2001501188489711743943

- GoldsteinMJPsycho-education and family treatment related to the phase of a psychotic disorderInt Clin Psychopharmacol199611Suppl 27783

- RobinsonDGWoernerMGAlvirJMPredictors of treatment response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorderAm J Psychiatry1999156454454910200732

- AzrinSTGoldsteinABHeinssenRKExpansion of coordinated specialty care for first-episode psychosis in the USFocal Point: Youth, Young Adults, and Mental Health201630911

- KaneJMRobinsonDGSchoolerNRComprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment programAm J Psychiatry2016173436237226481174

- SrihariVHTekCKucukgoncuSFirst-episode services for psychotic disorders in the U.S. public sector: a pragmatic randomized controlled trialPsychiatr Serv201566770571225639994

- SrihariVHTekCPollardJReducing the duration of untreated psychosis and its impact in the US: the STEP-ED studyBMC Psychiatry201414133525471062

- PerkinsDOGuHBotevaKLiebermanJARelationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysisAm J Psychiatry2005162101785180416199825

- MarshallMLewisSLockwoodADrakeRJonesPCroudaceTAssociation between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic reviewArch Gen Psychiatry200562997598316143729

- McGlashanTHDuration of untreated psychosis in first-episode schizophrenia: marker or determinant of course?Biol Psychiatry199946789990710509173

- BreitbordeNJMoeAMEredAEllmanLMBellEKOptimizing psychosocial interventions in first-episode psychosis: current perspectives and future perspectivePsychol Res Behav Manag20171011912828490910

- MelleILarsenTKHaahrUReducing the duration of untreated first-episode psychosis: effects on clinical presentationArch Gen Psychiatry200461214315014757590

- ChongSAMythilySVermaSReducing the duration of untreated psychosis and changing help-seeking behaviour in SingaporeSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol200540861962116091855

- Lloyd-EvansBCrosbyMStocktonSInitiatives to shorten duration of untreated psychosis: systematic reviewBr J Psychiatry2011198425626321972275

- JansenJEWøldikePMHaahrUHSimonsenEService user perspectives on the experience of illness and pathway to care in first-episode psychosis: a qualitative study within the TOP projectPsychiatr Q2015861839425464933

- BirchwoodMConnorCLesterHReducing duration of untreated psychosis: care pathways to early intervention in psychosis servicesBr J Psychiatry20132031586423703317

- AndersonKKFuhrerRMallaAK“There are too many steps before you get to where you need to be”: help-seeking by patients with first-episode psychosisJ Ment Health201322438439522958140

- TrickettEJMultilevel community-based culturally situated interventions and community impact: an ecological perspectiveAm J Community Psychol2009433–425726619333751

- SaegertSCKlitzmanSFreudenbergNCooperman-MroczekJNassarSHealthy housing: a structured review of published evaluations of US interventions to improve health by modifying housing in the United States, 1990–2001Am J Public Health20039391471147712948965

- DaltonJHEliasMJWandersmanACommunity Psychology: Linking Individuals and CommunitiesBelmontThomson Wadsworth2001

- BronfenbrennerUThe Ecology of Human DevelopmentCambridgeHarvard University1979

- BirchwoodMTrowerPBrunetKGilbertPIqbalZJacksonCSocial anxiety and the shame of psychosis: a study in first episode psychosisBehav Res Ther20074551025103717005158

- KimhyDVakhrushevaJJobson-AhmedLTarrierNMalaspinaDGrossJJEmotion awareness and regulation in individuals with schizophrenia: implications for social functioningPsychiatry Res20122002–319320122749227

- SkeateAJacksonCBirchwoodMJonesCDuration of untreated psychosis and pathways to care in first-episode psychosisBr J Psychiatry Suppl200243s73s7712271804

- NormanRMMallaAKVerdiMBHassallLDFazekasCUnderstanding delay in treatment for first-episode psychosisPsychol Med200434225526614982131

- ReedSIFirst-episode psychosis: a literature reviewInt J Ment Health Nurs2008172859118307596

- JormAFMental health literacy: empowering the community to take action for better mental healthAm Psychol201267323124322040221

- RickwoodDJDeaneFPWilsonCJWhen and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems?Med J Aust20071877 SupplS35S3917908023

- CorriganPWWatsonACUnderstanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illnessWorld Psychiatry200211162016946807

- KesslerRCAmmingerGPAguilar-GaxiolaSAlonsoJLeeSUstunTBAge of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literatureCurr Opin Psychiatry200720435936417551351

- ArnettJJEmerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twentiesAm Psychol200055546948010842426

- AddingtonJPennDWoodsSWAddingtonDPerkinsDOSocial functioning in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosisSchizophr Res200899111912418023329

- HoranWPSubotnikKLSnyderKSNuechterleinKHDo recent-onset schizophrenia patients experience a “social network crisis”?Psychiatry200669211512916822191

- TrottaADi FortiMMondelliVPrevalence of bullying victimisation amongst first-episode psychosis patients and unaffected controlsSchizophr Res2013150116917523891482

- CampbellMLMorrisonAPThe relationship between bullying, psychotic-like experiences and appraisals in 14–16-year oldsBehav Res Ther20074571579159117229400

- SpearLPNeurobehavioral changes in adolescenceCurr Dir Psychol Sci200094111114

- FranzLCarterTLeinerASBergnerEThompsonNJComptonMTStigma and treatment delay in first-episode psychosis: a grounded theory studyEarly Interv Psychiatry201041475620199480

- AndersonKKFuhrerRWynantWAbrahamowiczMBuckeridgeDLMallaAPatterns of health services use prior to a first diagnosis of psychosis: the importance of primary careSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol20134891389139823429939

- LincolnCHarriganSMcGorryPDUnderstanding the topography of the early psychosis pathways: an opportunity to reduce delays in treatmentBr J Psychiatry Suppl19981723321259764122

- McFarlaneWRMultifamily Groups in the Treatment of Severe Psychiatric DisordersNew YorkGuilford Press2004

- BreitbordeNJWoodsSWSrihariVHMultifamily psychoeducation for first-episode psychosis: a cost-effectiveness analysisPsychiatr Serv200960111477148319880465

- MackrellLLavenderTPeer relationships in adolescents experiencing a first episode of psychosisJ Ment Health2004135467479

- McGorryPBatesTBirchwoodMDesigning youth mental health services for the 21st century: examples from Australia, Ireland and the UKBr J Psychiatry Suppl201354s30s3523288499

- DixonLBGoldmanHHBennettMEImplementing coordinated specialty care for early psychosis: the RAISE Connection ProgramPsychiatr Serv201566769169825772764

- BreitbordeNJKMoeAMEarly intervention in psychosis in the United States: from science to policy reformPolicy Insights Behav Brain Sci2017417987

- UzenoffSRPennDLGrahamKASaadeSSmithBBPerkinsDOEvaluation of a multi-element treatment center for early psychosis in the United StatesSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol201247101607161522278376

- BreitbordeNJBellEKDawleyDThe Early Psychosis Intervention Center (EPICENTER): development and six-month outcomes of an American first-episode psychosis clinical serviceBMC Psychiatry20151526626511605

- McGorryPDThe specialist youth mental health model: strengthening the weakest link in the public mental health systemMed J Aust20071877 SupplS53S5617908028

- MallaAIyerSMcGorryPFrom early intervention in psychosis to youth mental health reform: a review of the evolution and transformation of mental health services for young peopleSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol201651331932626687237

- BreitbordeNJKLabrequeLMoeAMGaryTMeyerMCommunity-academic partnership: establishing the Institute for Mental Health Research Early Psychosis Intervention CenterPsychiat Serv2018695505507

- BreitbordeNJKLabrecqueLMoeAGaryTMeyerMCommunity-academic partnership: establishing the Institute for Mental Health Research Early Psychosis Intervention Center (IMHR-EPICENTER)2018695505507

- AndersonKKFuhrerRMallaAKThe pathways to mental health care of first-episode psychosis patients: a systematic reviewPsychol Med201040101585159720236571

- HaddockGTarrierNMorrisonAPHopkinsRDrakeRLewisSA pilot study evaluating the effectiveness of individual inpatient cognitive-behavioural therapy in early psychosisSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol199934525425810396167

- BreitbordeNJKWoodsSWPollardJAge and social support moderate the relationship between geographical location and access to early intervention programs for first-episode psychosisEarly Interv Psychiatry20082A73

- BickmanLContinuum of care. More is not always betterAm Psychol19965176897018694389

- WeiszJRHanSSValeriSMMore of what? Issues raised by the Fort Bragg studyAm Psychol19975255415459145022

- WeiszJRNgMYBearmanSKOdd couple? Reenvisioning the relation between science and practice in the dissemination-implementation eraClin Psychol Sci2014215874

- MartyDRappCMcHugoGWhitleyRFactors influencing consumer outcome monitoring in implementation of evidence-based practices: results from the National EBP Implementation ProjectAdm Policy Ment Health200835320421118058219

- LindamerLALebowitzBDHoughRLPublic-academic partnerships: Improving care for older persons with schizophrenia through an academic-community partnershipPsychiatr Serv200859323623918308902

- SalyersMPMcKassonMBondGRMcGrewJHRollinsALBoyleCThe role of technical assistance centers in implementing evidence-based practices: lessons learnedAm J Psychiatr Rehab200710285101

- RyanRMDeciELSelf-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-beingAm Psychol2000551687811392867

- GagnéMDeciELSelf-determination theory and work motivationJ Organ Behav2005264331362

- AaronsGAMental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS)Ment Health Serv Res200462617415224451

- AaronsGAWellsRSZagurskyKFettesDLPalinkasLAImplementing evidence-based practice in community mental health agencies: a multiple stakeholder analysisAm J Pub Health200999112087209519762654

- MallaAJordanGJooberRA controlled evaluation of a targeted early case detection intervention for reducing delay in treatment of first episode psychosisSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol201449111711171824902532

- LeveySHowellsKLeveySDangerousness, unpredictability and the fear of people with schizophreniaJ Forens Psychiatry1995611939

- WalshEBuchananAFahyTViolence and schizophrenia: examining the evidenceBr J Psychiatry2002180649049512042226

- NordtCRösslerWLauberCAttitudes of mental health professionals toward people with schizophrenia and major depressionSchizophr Bull200632470971416510695

- GoodwinJThe horror of stigma: psychosis and mental health care environments in twenty-first-century horror film (Part II)Perspect Psychiatr Care201450422423425324026

- DickensEGAn evaluation of mental health stigma perpetuated by Horror Video gamingYoung Res201711108117

- WahlODepictions of mental illnesses in children’s mediaJ Ment Health2003123249258

- VahabzadehAWittenauerJCarrEStigma, schizophrenia and the media: exploring changes in the reporting of schizophrenia in major U.S. newspapersJ Psychiatr Pract201117643944622108403

- LivingstoneSYoung People and New Media: Childhood and the Changing Media EnvironmentLondonSage2002

- GronholmPCThornicroftGLaurensKREvans-LackoSMental health-related stigma and pathways to care for people at risk of psychotic disorders or experiencing first-episode psychosis: a systematic reviewPsychol Med201747111867187928196549

- WahlOFMental health consumers: experience of stigmaSchizophr Bull199925346747810478782

- GriffithsKMCarron-ArthurBParsonsAReidREffectiveness of programs for reducing the stigma associated with mental disorders. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsWorld Psychiatry201413216117524890069

- LópezSRLara MdelDCKopelowiczASolanoSFoncerradaHAguileraALa CLAve to increase psychosis literacy of Spanish-speaking community residents and family caregiversJ Consult Clin Psychol200977476377419634968

- CattsSVO’TooleBICarrVJAppraising evidence for intervention effectiveness in early psychosis: conceptual framework and review of evaluation approachesAustr N Z J Psychiatry2010443195219

- HeinssenRMcGorryPNordentoftMRAISE 2.0: establishing a national Early Psychosis Intervention Network in the USEarly Interv Psychiatry201610Suppl 14

- GoldmanHHKarakusMFreyWBeronioKEconomic grand rounds: financing FEP services in the United StatesPsychiatr Serv201364650650823728599

- CorrellCURobinsonDGSchoolerNRCardiometabolic risk in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: baseline results from the RAISE-ETP studyJAMA Psychiatry201471121350136325321337

- OlfsonMGerhardTHuangCCrystalSStroupTSPremature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United StatesJAMA Psychiatry201572121172118126509694

- VancampfortDCorrellCUWampersMMetabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of prevalences and moderating variablesPsychol Med201444102017202824262678

- MelleIOlav JohannesenJHaahrUHCauses and predictors of premature death in first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disordersWorld Psychiatry201716221721828498600

- MitchellAJLordOMaloneDDifferences in the prescribing of medication for physical disorders in individuals with v. without mental illness: meta-analysisBr J Psychiatry2012201643544323209089

- ScottDPlatania-PhungCHappellBQuality of care for cardiovascular disease and diabetes amongst individuals with serious mental illness and those using antipsychotic medicationsJ Healthc Qual20123451521

- WoodheadCAshworthMBroadbentMCardiovascular disease treatment among patients with severe mental illness: a data linkage study between primary and secondary careBr J Gen Pract201666647e374e38127114210

- LiuNHDaumitGLDuaTExcess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: a multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendasWorld Psychiatry2017161304028127922

- NaslundJAWhitemanKLMcHugoGJAschbrennerKAMarschLABartelsSJLifestyle interventions for weight loss among overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysisGen Hosp Psychiatry2017478310228807143

- YeisenRAJoaIJohannessenJOOpjordsmoenSUse of medication algorithms in first episode psychosis: a naturalistic observational studyEarly Interv Psychiatry201610650351025588989