Abstract

The women’s global health agenda has recently been reformulated to address more accurately cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. The aim of the present work was to review the global and national policies and practices that address sex equality in health with a focus on CVDs in women. Scientific databases and health organizations’ websites that presented/discussed policies and initiative targeting to enhance a sex-centered approach regarding general health and/or specifically cardiac health care were reviewed in a systematic way. In total, 61 relevant documents were selected. The selected policies and initiatives included position statements, national action plans, evidence-based guidelines, guidance/recommendations, awareness campaigns, regulations/legislation, and state-of-the art reports by national/international projects and conferences. The target audiences of large stakeholders (eg, American Heart Association, European Society of Cardiology, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) were female citizens, health professionals, and researchers. Much as policy-makers have recognized the sex/gender gap in the CVD field, there is still much to be done. Thereby, tailor-made strategies should be designed, evaluated, and delivered on a global and most importantly a national basis to achieve gender equity with regard to CVDs.

Introduction

Since the introduction of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals in 2000, it been imperative for policy-makers around the globe to improve women’s sexual and reproductive health.Citation1 Much as this remains at the top of the list in the global agenda of women’s health, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) seem to be an even bigger threat, considering the enormous burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in terms of morbidity/mortality rates, life-years lost, poor quality of life, and direct or indirect health-care costs:Citation1,Citation2 18.1 million women died from NCDs, almost half attributed to CVDs, based on estimations for 2012.Citation1 Most importantly, besides the “success story” of the past four decades regarding the decline in age-adjusted CVD-mortality rates, this has not been the case in women, even the younger ones.Citation3

As underscored by Briones-Vozmediano et al, international and especially national health plans lack gender sensitivity.Citation4 This phenomenon is even more apparent in the case of CVDs. The lack of sex- and gender-sensitive studies in CVD research points to indicative defaults in the NCD-research field.Citation5 Underrepresentation of women in studies need to be addressed while important efforts are being demanded to effectively include sex/gender in health research and funding.Citation6 It is imperative to recognize that CVDs in women have long being sidelined in favor of the unanimously propagated claim that this chronic disease was supposed to be a male domain or that men and women were equally susceptible.Citation5 Nonetheless, indicative heterogeneity has been convincingly demonstrated regarding CVD manifestation, risk-factor burden, and disease prognosis between men and women, due not only to biological status (ie, sex) but also various social determinants (ie, gender identity).Citation5,Citation6 Most importantly, the lack of women’s awareness regarding this threat is impressive. The majority of women usually falsely recognize breast cancer as the principal cause of death in the female population.Citation7,Citation8 In this context, women are to wait longer between seeking and receiving medical advice.Citation9 On the other hand, female patients are susceptible to underdiagnosis, inappropriate therapeutic decisions, or even remaining untreated, as physicians usually underestimate their risk burden.Citation10,Citation11 Therefore, it is considered that the time has come for a sustained effort and commitment to encompass in the women’s health agenda tailor-made strategic plans regarding the effective prevention and management of CVD.Citation2 To manage these gender disparities, policy-makers around the globe should design, evaluate, and deliver strategies to increase awareness, enhance research, and optimize disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.Citation2 The goal of this review was to present what is actually happening in terms of policies and practices aimed at enhancing a sex-centered approach in health to highlight those specific to women’s cardiac health, with implications for public health practitioners and policy-makers to achieve gender equity with regard to CVD.

Methods

Literature Review

Our literature search included scientific papers in peer-reviewed journals, as well as any other relevant documents and organization websites (gray literature)presenting/discussing policies and initiatives targeting a sex-centered approach regarding CVDs. For scientific papers, Pubmed and Scopus were used, and the search was carried out from December 2019 to January 2020 and extended back to papers published in 1960. No restriction was made with regard to publication language or status. The search was completed using cross-referencing from the papers found, whereas forpapers in which additional information was required the authors were contacted via email. The search terms were cardiovascular disease(s), heart, gender, sex, women, female, disease, policy, public health, and strategic plan. Since scientific databases provide limited information on policies and practices in public health, the websites of the UN (www.un.org), WHO (www.who.int), AHA (www.americanheart.org), American College of Cardiology (www.acc.org), ESC (www.escardio.org), European Medicines Agency (www.ema.europa.eu), NIH (www.nih.gov), NHLBI (www.nhlbi.nih.gov), CDC (www.cdc.gov), BHF (www.bhf.org.uk), Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (http://www.heartandstroke.com), and other national cardiac societies and foundations were searched for relevant position statements and any other documents referring to the aims of present to find as much information as possible. Based on the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition of the term “policy” (https://www.cdc.gov/policy/analysis/process/definition.html), types of manuscripts selected in the present review included position statements,discussion papers and articles supportive of the scientific community, national action plans, evidence-based guidelines, guidance/recommendations, awareness campaigns, regulations/legislation, state-of-the-art reports by international projects and national/international conferences, and other relevant initiatives/practices. Policies and practices had to state or speculate on their main objectives of reduction in gender equity in general health and/or in cardiac health care. The manuscripts selected to cover the purposes of the present work were reviewed by two independent authors (MK and DP) following a systematic approach.

Results

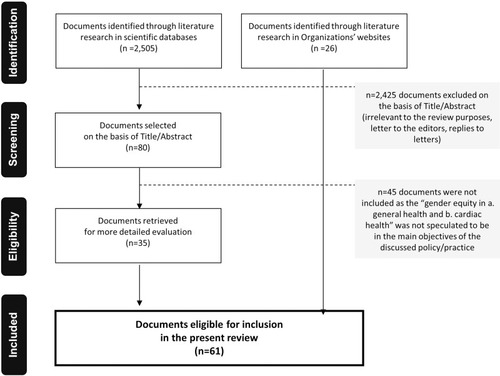

In total, 35 publications in the scientific databases were considered relevant to the present work. In addition to those, 26 documents/references regarding global and national policies and practices were retrieved from the aforementioned organization websites and are discussed here. The flow diagram of the literature search is presented in .

Sex-Specific Reporting in Global Health Agenda: Policies and Practices

Results from the initiatives regarding the consideration of sex in global initiatives are summarized in . The NIH was among the very first references regarding this issue: in 1994, policy guidance regarding the consideration of women in clinical trials was published.Citation12 Updated versions were released in 2000 and 2001.Citation13,Citation14 In 1995, in a report from the Fourth World Conference on Women, the UN underscored the fact that a policy decision should be published only after a sex-specific evaluation regarding its effectiveness.Citation15 Additionally, it has been about two decades since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) established the Office of Women’s Health, targeting the need to manage the underrepresentation of women in general and women in particular situations (eg, pregnancy) in medical clinical trials. In this context, in 1993 guidance for researchers on this issue was published, while in 2014 the FDA published an action plan to address the collection and availability of subgroup data, including sex.Citation16,Citation17 Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health; Does Sex Matter? and Women’s Health Research: Progress, Pitfalls, and Promise, published by the Institute of Medicine in 2001 and 2010, respectively, were milestones for global health research and policy-making and among of the very first official recognitions of sex (ie, the biological dimension) and gender (ie, the socially constructed dimension) as variables with critical health impact, interacting with each other.Citation18,Citation19 In 2010, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and its Institute of Gender and Health subdivision revealed a user-friendly tool for health researchers regarding the integration of sex and gender in their study design.Citation20 In 2014, the WHO provided guidance on the integration of gender-responsive sustainable approaches and promoted disaggregated data analysis and health-inequality monitoring.Citation21 In 2015, the NIHrecommended sex-specific reporting in any kind of study or an evidence-based justification for its omission.Citation22 At the same time, the UN underscored the necessity for gender-sensitive strategies in all sustainable development goals for 2030, while the fifth sustainable goal was incorporated to “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.”Citation23 In 2015, the League of European Research Universities published a list of recommendations for universities, governments, funders, and peer-reviewed journals to adopt strategies and policies toward a gendered research and innovation approach.Citation24 The Lancet Commission on Women and Health in 2015 recognized women’s health as a key factor in sustainable development.Citation25 In 2016, the report “Women’s health: a new global agenda” provided a redefinition of the women’s health agenda, setting different priorities according to the reality depicted by disease-epidemiology data around the globe.Citation26 In this context, the Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s, and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030) was published by the WHO–UN Secretary-General partnership. The roadmap report provided recommendations to diminish all preventable deaths in women, children, and adolescents, making a commitment to reducing premature NCD mortality by a third by 2030.Citation27 Shortly thereafter, the European Association of Editors published a set of reporting guidelines (Sex and gender equity in research) to provide to researchers and authors a tool to achieve sex- and gender-standardization in scientific publications, while the European Commission in the context of the Horizon 2020 program published guidance for addressing gaps in the participation of women in the EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation’s projects and to achieve gender balance in theknowledge, innovation, and technology produced.Citation28,Citation29

Table 1 Global Policies and practices to Address Gender Disparities in Health, with the Scientific Community as Target Audience

Female-Centered Policies and Practices in Global CVD

Results from initiatives regarding the consideration of sex in global CVD are summarized in . In 1986, a workshop was convened by the NIH NHLBI to lay the groundwork for researchers and clinicians to work onCVD in women, while in 1987 key highlights of the workshop were summarized in a report: “Coronary heart disease in women: reviewing the evidence, identifying the needs”. This was the very first initiative that brought the “female heart” out from the shadows.Citation30,Citation31

Table 2 Global Policies and Practices to Address Cardiovascular Diseases in Women on a Scientific and Community Basis

The “Guide to preventive cardiology for women” was the first official report with recommendations on CVD prevention and management in women, focusing on female-specific factors and medical treatments (eg, hormone-replacement therapy), and was issued by the AHA.Citation32 However, the first evidence-based women-centered guidelines on primary and secondary prevention of chronic vascular atherosclerotic diseases came in 2004.Citation33 Since then, two updates of this guidance have been published. Initially, the AHA underscored the common misconception that women and men are equal in terms of the disease and challenged the belief that the two sexes should be treated similarly.Citation34,Citation35 These guidelines highlighted the underrepresentation of females in clinical trials. Following that, health professionals were oriented toward a more sex-specific research approach, resulting in the potential for more definitive recommendations and passing from evidence-based strategies to the effectiveness-based preventive-action plans in 2011. Notably, in the last AHA-guideline update, some primary prevention strategies were proven to be inappropriate for women (ie, aspirin prescription), while it was underscored that women were susceptible to other comorbidities and conditions that multiplied their CVD risk, thus challenging the effectiveness and appropriateness of hitherto-typical prevention and management strategies.Citation35 In addition to this, in 2014 the first set of guidelines related on stroke prevention in women was published by the AHA in collaboration with the American Stroke Association.Citation36

In 2007, unique aspects of nonclinical factors that affect the health of women, termed “gendered structural determinants of health” in a 2007 report by the World Health Organization’s Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network, pointed to the health and outcomes of women at risk of or with CVD.Citation37 In the AHA’s journal Circulation, a themed issue focusing on women’s cardiac health (ie, CVD in women) highlighted major challenges and gaps in sex- and gender-centered CVD prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, calling on health professionals for additional research.Citation5,Citation38,Citation39 In 2017, a state-of-the-art review was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology that synthesized evidence and discussed issues related to health-care quality and equity for women, including minority-population subgroups.Citation40 The same year, the results of a survey conducted by the Women’s Heart Alliance were revealed, summarizing the knowledge, gapstherein, and perceptions, of women as well as physicians regarding CVD in women.Citation41

FDA Office of Women’s Health–funded projects have contributed to highlighting major gaps in the field of CVDs in women.Citation42 Nonetheless, apart from the limited number of high-quality sex-specific studies, the AHA recognized another challenge in CVD in women: CVD was the leading cause of death in females, yet many were unaware of this threat.Citation43 In 2002, the NHLBI — along with (among others) the AHA — teamed up to sponsor the Heart Truth awareness campaign with red dress as a centerpiece symbol and the message “Heart disease doesn’t care what you wear: it’s the #1 killer of women”, aimed at raising women’s awareness regarding their cardiac health and enhancing the knowledge of health professionals and researchers on this issue.Citation44 In 2004, a national campaign in the US called Go Red for Women was launched.Citation45 This campaign, which continues till this day, includes passionate, emotional, and social initiatives designed with a dual purpose: to empower women to take charge of their own cardiac health, and to support health professionals’ daily clinical practice. More than a decade later, this campaign has moved beyond the borders of the US to more than 50 countries around the globe.Citation45 In 2006, the Society for Women’s Health, in collaboration with a nonprofit organization called WomenHeart: The National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease (http://www.womenheart.org), released the “10Q report: advancing women’s heart health through improved research, diagnosis, and treatment” to encourage researchers and health practitioners toward female-specific cardiac care.Citation46 In 2011, the Make the Call, Don’t Miss A Beat campaign aimed at educating, engaging, and empowering women and their families to recognize the seven symptoms of a heart attack that most commonly present in women. This initiative included a comprehensive public service–advertising campaign.Citation47

Another initiative in the CVD spectrum focusing on women’s health was the WISEWOMAN (Well-Integrated Screening and Evaluation for Women Across the Nation) program started in 1993.Citation48 This program is administered by the CDC, specifically its division for heart disease and stroke prevention. The target group of the WISEWOMAN program is women with low financial status aged 40–64 years. The aim of the program is to provide free-of-charge heart-disease and stroke risk–factor screenings, namely blood-pressure control, along with evidence-based methods enhancing women’s adherence to healthier behaviors, so as to promote lifelong heart-healthy lifestyle changes. The contributors to this program focus on strategies being applicable to both health-care practitioners and on the basis of community targeting from clinicians and pharmacists to farmers’ markets, and were recently revealed in a technical assistance and guidance document.Citation48

A bill addressing the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of heart disease, stroke, and other CVDs in women was introduced in the American House of Representatives in November 2011, called the Heart Disease, Education, Analysis, Research, and Treatment for Women Act or the Heart for Women Act.Citation49 This legislation was set to ensure the availability of gender-specific information in medical treatments for health-care professionals, researchers, and the public to expand the CDC-funded WISEWOMAN project to 20 additional states of the US and to require the Secretary of Health and Human Services to perform an annual report for Congress on the quality of and access to health-care services for women. This bill was highly supported, among other relevant associations and nongovernmental organizations, by the AHA and its American Stroke Association division.Citation50

Heart centers for women were recently developed as a response to the need for improved outcomes for women with CVD.Citation51 These centers serve as a point of focus for the development of education and research programs to better address the unique features of CVD in women. The multidisciplinary approach to the care of women with or at risk of CVD has emphasized the importance of developing key clinical benchmarks to allow for standardization of care pathways. Stakeholders in such centers include representatives from internal medicine, family medicine, obstetrics and gynecology departments, and nursing programs.

The FDA Office of Women’s Health offers resources to help women and health-care providers get informed about heart health, including the Heart Health Social Media Toolkit to encourage women to protect their hearts. The toolkit includes resources for “everyday” women and health professionals, including sample social media messages and blog posts.Citation52 What is more, the Office of Women’s Health is partnering with the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health to raise awareness about diverse women of different ages, races, ethnic backgrounds, and health conditions participating in clinical trials. The Diverse Women in Clinical Trials Initiative includes a consumer-awareness campaign, as well as resources and workshops for health professionals and researchers.Citation53

In Europe, important attempts have been made at reformulatingthe women’s health agenda. In 2004, a workshop was held at the seventh European Policy Forum, based on which a report was released underscoring sex discrepancies in CVD diagnosis and treatment and challenges on a community basis.Citation54 Among the very first initiatives of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) was the Women at Heart program launched in 2005 aimed at coordinating research and educational initiatives regarding CVDs in females.Citation55 The program started with a policy conference in June 2005, during which experts’ opinions were selected, scientific gaps underscored, and strategic plans delineated to address this issue.Citation55 Highlights of the conference and the state of the art in Europe were summarized in a policy statement, available in various languages. In this policy statement, a flowchart with synergistic actions implemented by the ESC, EU, national scientific societies, and national health authorities at a European level was proposed to enhance researchs and other relevant scientific sectors (eg, research funders) to cover gender gaps in CVD investigation.Citation56 At the 2005 ESC Congress, a thematic subunit was devoted to CVDs in women so as to enhance dissemination of this information in the scientific community, while in 2006 an educational course was available. In national cardiac societies (ie, Swedish Cardiac Society, Polish Cardiac Society) rollout of the Women at Heart program was revealed.Citation56 From this perspective, the European Health Network and ESC jointly applied for a grant for the EuroHeart project, a consortium among 30 partners in 21 European countries.Citation57 Among the primary purposes of this project presented in its work package number 6 was “to question gender differences in the management of CVDs and consequently provide recommendations for research and regulatory policy-makers.”Citation58 This survey highlighted significant gender biases in the use of investigations and evidence-based medical treatments.Citation59,Citation60 In the context of this work package, a report called “Red alert on women’s hearts” was released in November 2009 for the scientific community.Citation61 Additionally, 60 and 15 awareness campaigns for women and their physicians in the participated in the project countries were launched, respectively.Citation61 In 2008, a short guide called “Assessment and management of cardiovascular risks in women” was published by a joint workshop under the auspices of the ESC, European Society of Hypertension, and International Menopause Society aimed at assisting menopause physicians in contributing to the overall management of women’s cardiac health.Citation62 In 2011, the ESC published guidelines on the management of CVDs during pregnancy, while an updated version was launched in 2018.Citation63,Citation64 In the very recent ESC prevention in clinical practice guidelines, some female-specific conditions were reported (eg, polycystic ovarian syndrome, pregnancy complications), yet a large scientific gap was clearly stated: “The young women . . . continue to be underrepresented in clinical trials . . . Information on whether female-specific conditions improve risk classification in women is unknown”.Citation65

The BHF has launched pages (eg, the “Women’s Room”) on its website aimed at increasing awareness of women regarding heart disease and stroke, related risk factors and symptomatology of a cardiac episode.Citation66 In 2015, the BHF launched a campaign called Bag it. Beat it, which continues today, with the purpose of increasing funding of research focusing on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of CVDs in women.Citation66 In 2010, a 2-day summit — Women and heart disease: a summit to eliminate untimely deaths in women — was held in Minneapolis to give straightforward directions on focusing areas of strategies and policies to ameliorate the health outcomes of women with heart disease in Minessota.Citation67

In 2000, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, University of Ottawa, and University of Alberta released a statement report with recommendations concerning policy development for a healthier female heart so as to support researchers, health practitioners, and policy-makers in creating a community where women, irrespective of their socioeconomic status, would receive effective medical care.Citation68 The Heart Institute in the University of Ottawa has launched the Canadian Women’s Heart Health Centre (https://cwhhc.ottawaheart.ca) with the aim of reducing CVDs in women throughmotivating individuals, health professionals, and health-care workers to address this public health concern. This initiative has been disseminated at national events and on social media to generate publicity of women’s health. Several training workshops have been organized by female survivors of heart attacks so as to motivate other women to pursue a healthier lifestyle and bring into being adequate preventive medical control to avoid suffering a heart attack. More specifically, the Women@Heart program has 12 two-hour sessions and is held biweekly in community settings across the region, while a similar initiative called the Improve Postpartum Program has been launched for women having suffered from preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension and as a result with high CVD risk.Citation69,Citation70 National cardiac/heart associations, such as the Hellenic Cardiac Society, Danish Heart Foundation, and Italian Heart Foundation, have introduced small initiatives on this issue.Citation71 In 2011 and 2012, two position statements were revealed by the International Council on Women’s Health Issues (ICWHI), an international nonprofit organization aimed at empowering women’s health. In these, the necessity of recognizing and addressing the needs of women with regard to chronic diseases with focus oriented toward CVDs was underscored for researchers, health practitioners, and policy-makers.Citation72,Citation73

Discussion

This review reveals that much as there are some public health initiatives, from policy statements to awareness campaigns, toward acieving gender equity in CVD and supporting women’s cardiac health, their resonance within the scientific community remains low, with underrepresentation of women in CVD studies, lack of awareness of citizens and health practitioners, and absence of gender-sensitive analysis in scientific works. Additionally, the vast majority of such initiatives are located in the US, with fewer in Europe and scarce well-organized, integrated, focused plans on a national basis. Moreover, the dissemination of all these policies and practices seems too low to motivate the scientific community adequately.

Too few women are aware of CVD. This was firstly identified by the AHA in 1997, where they found that only one in three women were able correctly to identify heart disease as their sex’s leading cause of death.Citation74 The aforementioned campaigns and other initiatives to educate the public and increase support for women’s heart disease have contributed to a significant improvement in the level of women’s awareness regarding their cardiac health that has doubled since 1997. Nevertheless, this remains substandard, and has not improved significantly since 2006, particularly in younger and ethnic minority women, as well as those of low socioeconomic status.Citation75,Citation76 Younger women and racial and ethnic minorities have lower rates of awareness, higher rates of CVD mortality, and more risk factors.Citation76 In particular, they are less aware of their risks, have delayed diagnosis, face inconsistent responses from the health-care system, have their disease severity underestimated, receive suboptimal treatment, and ultimately have worse outcomes. This is more evident in women aged 35–54 years, in those with lower education, and among racial and ethnic minorities. Focusing on younger patients, prospective cohort studies, such as GENESIS-PRAXY and VIRGO, have revealed some sex differences in demographic, CV risk factors, symptoms, and treatment.Citation77,Citation78 Additionally, the social determinants of CVD in women have been much discussed, including health literacy, lower education, low-wage jobs, higher rates of poverty, and more familial responsibilities, coupled with societal discriminatory norms and practices.Citation40

At the same time, physicians also appear to ahow gaps regarding women’s cardiac health. In particular, physicians are more likely to assign a lower CVD risk category to female patients and underestimate CVD risk in women.Citation79 They are also less likely to refer women and ethnic minorities for diagnostic cardiac catheterization.Citation80 In a 2012 online survey, only one in five women reported that their physicians had ever discussed their risk of heart disease.Citation81 Women often receive suboptimal CVD-preventive care.Citation78 A couple of years later, the Women’s Heart Alliance survey selected 200 primary-care providers and 100 cardiologists to determine their self-reported readiness to address CVD risk in women patients. Primary-care providers reported CVD as a principal health concern in women, yet less important than breast- and weight-related health. Moreover, most physicians, including one in two cardiologists, reported suboptimal training in assessing CVD risk in women.

Implications for Future Policies and Practices in CVD

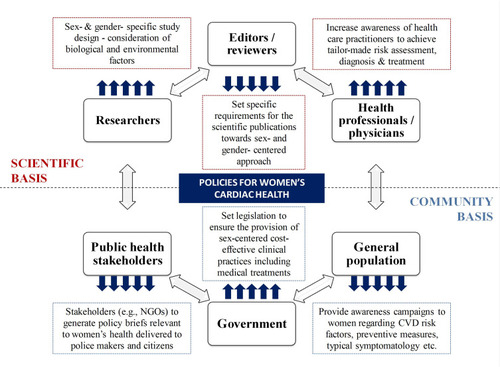

To optimize women’s cardiac health, policy-makers should recognize, promote, and allocate resources to address sex- and gender-specific issues in prevention, risk assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation in CVDs.Citation82 Policies should be accordingly designed after a cautious needs-assessment process to evaluate the actual demands at a national level. Based on the public health initiatives discussed, it is suggested that priority setting for CVD prevention and control include a successful combination of policy-makers/stakeholders, researchers, and health-care systems. Thereby, a multidimensional approach, as suggested in is demanded to support the generation of evidence-based, cost-effective, and tailor-made decisions in policy-making. Through this multidimensional approach, specific goals should be set, including (among others) the incorporation of sex- and gender-based guidelines in CVD prevention, management, and rehabilitation, provision of comprehensive patient-centered care customized to address cultural, ethnic, spiritual, and social determinants of the patient, and implementation of multidisciplinary health-care teams for women incorporating clinicians caring for women to improve quality and address health-care gaps for women: family physicians, primary-care physicians, obstetricians, gynecologists, nurse practitioners, emergency-department physicians, and nurses. What is more, women’s education in terms of health-literacy improvement regarding CVD is equally important. Finally, community partnership and commitment to research with the focus oriented toward the most vulnerable subgroups (eg, younger women, women of low socioeconomic status, and ethnic minorities) should be an indispensable part of such approaches.

Conclusion

Much as the past two decades have seen substantial effort being put into improving women’s health on the whole, there is still much to be done. Giving a broader definition to women’s health, primary and secondary prevention of CVDs has started to be prioritized, and important initiatives have been launched toward this approach. To achieve this, global and most importantly national sectors should perform appropriate policy-making to support sex- and gender-sensitive collection, usage, and interpretation of health data and enhance the level of awareness in citizens and health professionals. In a world with finite resources, where there is imperative need to maximize the cost-effectiveness of prevention and management strategies, health disparities have to be addressed by health practitioners, and the case of women in CVD care remains an ongoing public health concern.

Abbreviations

AHA, American Heart Association; BHF, British Heart Foundation; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CDC, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; NHLBI, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIH, National Institutes of Health; NCDs, noncommunicable diseases; UN, United Nations; WHO, World Health Organization.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health in 2015 from MDGs, Millenium Development Goals to SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. 2015 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/200009/1/9789241565110_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 18, 2020.

- Norton R. Women’s health: a new global agenda. Womens Health (Lond). 2016;12(3):271‐273.

- Wilkins E, Wilson L, Wickramasinghe K, et al.: European HEART NETWORK, Brussels. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2017. 2017 Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/publications/statistics/european-cardiovascular-disease-statistics-2017. Accessed 18, 2020.

- Briones-Vozmediano E, Vives-Cases C, Peiró-Pérez R. Gender sensitivity in national health plans in Latin America and the European Union. Health Policy (New York). 2012;106(1):88‐96. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.03.001

- Garcia M, Mulvagh SL, Merz CN, Buring JE, Manson JE. Cardiovascular Disease in Women: clinical Perspectives. Circ Res. 2016;118(8):1273‐1293. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307547

- Sharman Z, Johnson J. Towards the inclusion of gender and sex in health research and funding: an institutional perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(11):1812‐1816. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.039

- Bairey Merz CN, Andersen H, Sprague E, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding cardiovascular disease in women: the women’s heart alliance [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 22;70(8):1106-1107]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(2):123‐132.

- Webster R, Heeley E. Perceptions of risk: understanding cardiovascular disease. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2010;3:49‐60.

- Kouvari M, Yannakoulia M, Souliotis K, Panagiotakos DB. Challenges in sex- and gender-centered prevention and management of cardiovascular disease: implications of genetic, metabolic, and environmental paths. Angiology. 2018;69(10):843‐853. doi:10.1177/0003319718756732

- Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Kourlaba G, et al. Sex-related characteristics in hospitalized patients with acute coronary syndromes–the Greek Study of Acute Coronary Syndromes (GREECS). Heart Vessels. 2007;22(1):9‐15. doi:10.1007/s00380-006-0932-2

- Lee SK, Khambhati J, Varghese T, et al. Comprehensive primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40(10):832‐838. doi:10.1002/clc.22767

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH Guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research: NIH Guide, Volume 23, Number 11, 1994. Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not94-100.html. Accessed 18, 2020.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research - Updated 2000. 2000 Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/women_min/guidelines_update.htm. Accessed 18, 2020.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH Policy and Guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research - 2001. 2001 Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-02-001.html. Accessed 18, 2020.

- United Nations (UN). Beijing Declaration and Platform of Action UN Women. Report on the Fourth World Conference on Women. 1995 Available from: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/pdf/Beijing%20full%20report%20E.pdf. Accessed 1, 2020.

- Federal Register: Department of Health and Human Services. Guideline for the study and evaluation of gender differences in the clinical evaluation of drugs; Notice, July 1993; 58 (139). www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM126835.pdf. Available from: Accessed 18, 2020.

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA Action plan to enhance the collection and availability of demographic subgroup data. 2014 Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/SignificantAmendmentstotheFDCAct/FDASIA/UCM410474.pdf. Accessed 18, 2020.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter? Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001 Available form: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222288/. Accessed 18, 2020.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). Women’s Health Research: Progress, Pitfalls, and Promise. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press;2010. doi:10.17226/12908.

- Canadian Institute of Health Research-Institute of Gender and Health. Sex, gender and health research guide: a tool for CIHR Applicants. 2010 Available from: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/32019.html. Accessed 18, 2020.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Roadmap for Action (2014-2019): Integrating Equity, Gender, Human Rights and Social Determinants into the Work of WHO. Geneva; 2015 Available from: http://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/web-roadmap.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 18, 2020.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). Consideration of Sex as a Biological Variable in NIH-funded Research. 2015 Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-15-102.html. Accessed 18, 2020.

- United Nations (UN). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015 Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld. Accessed 18, 2020.

- League of European Research Universities (LERU). Gendered research and innovation: integrating sex and gender analysis into the research process. 2015 Available from: http://media.leidenuniv.nl/legacy/leru-paper-gendered-research-and-innovation.pdf. Accessed 18, 2020.

- Langer A, Meleis A, Knaul FM, et al. Women and Health: the key for sustainable development. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1165‐1210. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60497-4

- Norton R, Peters S, JHA V, Kennedy S, Woodward M: Oxford Martin School. Oxford Martin Policy Paper, Women’s health: a new global agenda. 2016 Available from: https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/briefings/women’s-health.pdf. Accessed 18, 2020.

- United Nations (UN). Every woman, every child. global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health. 2015 Available from: http://who.int/life-course/partners/global-strategy/globalstrategyreport2016-2030-lowres.pdf. Accessed 18, 2020.

- De Castro P, Heidari S, Babor TF. Sex And Gender Equity in Research (SAGER): reporting guidelines as a framework of innovation for an equitable approach to gender medicine. Commentary. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2016;52(2):154‐157.

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Research & Innovation. H2020 Programme. Guidance on Gender Equality in Horizon 2020. 2016 Available from: http://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/h2020-hi-guide-gender_en.pdf.. Accessed 18, 2020.

- Eaker ED, Packard B, Wenger NK, Clarkson TB, Tyroler HA, Eds.. Coronary Heart Disease in Women: Proceedings of an NIH Workshop. New York: Haymarket Doyma; 1987.

- Hayes SN, Wood SF, Mieres JH, Campbell SM, Wenger NK. Scientific advisory council of womenheart: the national coalition for women with heart disease. Taking a giant step toward women’s heart health: finding policy solutions to unanswered research questions. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25(5):429‐432. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2015.07.001

- Mosca L, Grundy SM, Judelson D, et al. AHA/ACC scientific statement: consensus panel statement. Guide to preventive cardiology for women. American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(6):1751‐1755.

- Mosca L, Appel LJ, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2004;109(5):672‐693. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000114834.85476.81

- Mosca L, Banka CL, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(11):1230‐1250. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.020

- Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women–2011 update: a guideline from the american heart association [published correction appears in Circulation. 2011 Jun 7; 123(22):e624][published correction appears in Circulation. 2011 Oct 18;124(16):e427]. Circulation. 2011;123(11):1243‐1262.

- Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA, et al. American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(5):1545–1588.24503673

- World Health Organization. Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: why it exists and how we can change it. Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network. 2007.

- Blenck CL, Harvey PA, Reckelhoff JF, Leinwand LA. The importance of biological sex and estrogen in rodent models of cardiovascular health and disease. Circ Res. 2016;118(8):1294‐1312. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307509

- Menazza S, Murphy E. The expanding complexity of estrogen receptor signaling in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 2016;118(6):994‐1007. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.305376

- Shaw LJ, Pepine CJ, Xie J, et al. Quality and equitable health care gaps for women: attributions to sex differences in cardiovascular medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(3):373–388. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.05128705320

- Bairey Merz CN, Andersen H, Sprague E, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding cardiovascular disease in women: the women’s heart alliance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(2):123–132.28648386

- Elahi M, Eshera N, Bambata N, et al. The food and drug administration office of women’s health: impact of science on regulatory policy: an update. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(3):222‐234. doi:10.1089/jwh.2015.5671

- Mosca L, Ferris A, Fabunmi R, Robertson RM, American Heart Association. Tracking women’s awareness of heart disease: an American Heart Association national study. Circulation. 2004;109(5):573‐579. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000115222.69428.C9

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The “Heart Truth” campaign: a program from of the National Institutes of Health. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/hearttruth/. Accessed 081 2020.

- American Heart Association (AHA). Go Red for Women. Available from: https://www.goredforwomen.org/. Accessed 081 2020.

- Wenger NK, Hayes SN, Pepine CJ, Roberts WC. Cardiovascular care for women: the 10-Q Report and beyond. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112(4):S2. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.06.00223910053

- American Heart Association. 2011 Make the Call, Don’t Miss A Beat. Available from: http://www.abcardio.org/articles/makethecall.html.

- Center of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention (2014) Well-integrated Screening and Evaluation for Women Acrossthe Nation (WISEWOMAN). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/wisewoman/docs/ww_technical_assistance_guidance.pdf. Accessed 081 2020.

- House of Representatives: 112th Congress (2011-2012) Heart Disease, Education, Analysis, Research, Treatment for Women Act (Heart for Women Act. 2011 https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/3526/all-info. Accessed 18, 2020.

- American Heart Association (AHA, American Stroke Association (ASA)). Bill Summary: S. 438/H.R. 3526. Heart disease Education, Analysis, Research, and Treatment for Women Act (HEART for Women Act): a bill to improve the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of heart disease and stroke in women. 2011 Available from: https://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heartpublic/@wcm/@adv/documents/downloadable/ucm_435251.pdf. Accessed 1, 2020.

- Lundberg GP, Mehta LS, Sanghani RM, et al. Heart centers for women: historical perspective on formation and future strategies to reduce cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2018;138(11):1155–1165. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.03535130354384

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Heart Health for Women. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/consumers/womens-health-topics/heart-health-women. Content current as of March 2020.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Women in Clinical Trials. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/consumers/womens-health-topics/women-clinical-trials. 2019.

- European Health Network (EHN), European Health Management Association, Squibb B-M. A health heart for women. 7th European Health Policy Forum - Workshop: Challenges for a healthy heart for European women. 2004 Available from: http://www.ehnheart.org/projects/102:a-healthy-heart-for-european-women.html. Accessed 18, 2020.

- European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Women at Heart - Commited to improving heart health for women. 2004 Available from: https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/What-we-do/Initiatives/Women-at-heart/Women-at-Heart. Accessed 18 2020.

- Stramba-Badiale M, Fox KM, Priori SG, et al. Cardiovascular diseases in women: a statement from the policy conference of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(8):994‐1005.

- European Society of Cardiology (ESC), European Heart Network (EHN) The “EuroHeart” project: european Heart Health Strategy. 2007 Available from: http://www.ehnheart.org/projects/euroheart/about.html. Accessed 081 2020..

- Marco Stramba-Badiale European Heart Health Strategy, EuroHeart Project, Work Package 6: women and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2009 Available from: https://www.escardio.org/static_file/Escardio/EU-Affairs/WomensHeartsRedAlert.pdf. Accessed 081 2020.

- Daly C, Clemens F, Lopez Sendon JL, et al. Gender differences in the management and clinical outcome of stable angina. Circulation. 2006;113(4):490‐498. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.561647

- Dagres N, Nieuwlaat R, Vardas PE, et al. Gender-related differences in presentation, treatment, and outcome of patients with atrial fibrillation in Europe: a report from the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(5):572‐577. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.047

- Maas AH, van der Schouw YT, Regitz-Zagrosek V, et al. Red alert for women’s heart: the urgent need for more research and knowledge on cardiovascular disease in women: proceedings of the workshop held in Brussels on gender differences in cardiovascular disease, 29 September 2010. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(11):1362‐1368. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr048

- European Society of Cardiology (ESC), European Society of Hypertension and International Menopause Society. Assessment and management of cardiovascular risks in women. 2008 Available from: http://www.imsociety.org/downloads/assessment_and_management_of_cardiovascular_risks_in_women/english.pdf. Accessed 18, 2020.

- European Society of Gynecology (ESG); Association for European Paediatric Cardiology (AEPC); German Society for Gender Medicine (DGesGM), Regitz-Zagrosek V, Blomstrom Lundqvist C, et al. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. ESC Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2011;32(24):3147–3197.21873418

- ESC Scientific Document Group, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(34):3165–3241.30165544

- Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315‐2381.

- British Heart Foundation (BHF). Bag it. Beat it. Available from: https://bagit.bhf.org.uk/. Accessed 1 8 2020.

- Lindquist R, Boucher JL, Grey EZ, et al. Eliminating untimely deaths of women from heart disease: highlights from the Minnesota Women’s Heart Summit. Am Heart J. 2012;163(1):39‐48.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.020

- Plotnikoff RC, Hugo K, Wielgosz A, Wilson E, MacQuarrie D. Heart disease and stroke in Canadian women: policy development. Can J Public Health. 2000;91(1):58‐59. doi:10.1007/BF03404255

- Canadian Women’s Heart Health Centre. Women@Heart Program. University of Ottawa. Heart Institute Available from https://cwhhc.ottawaheart.ca/programs-and-services/womenheart-program..

- Canadian Women’s Heart Health Centre: University of Ottawa, Heart Institute Programs and activities. Available from: https://cwhhc.ottawaheart.ca/programs-and-services. Accessed 18, 2020.

- Hellenic Cardiac Society (HCS). National Action Plan for Cardiovascular Diseases (2008-2012). 2008 Available from: http://www.moh.gov.gr/articles/health/domes-kai-draseis-gia-thnygeia/ethnika-sxedia-drashs/95-ethnika-sxedia-drashs?fdl=228. Accessed 18, 2020.

- Davidson PM, McGrath SJ, Meleis AI, et al. The health of women and girls determines the health and well-being of our modern world: a white paper from the International Council on Women’s Health Issues. Health Care Women Int. 2011;32(10):870‐886. doi:10.1080/07399332.2011.603872

- Davidson PM, Meleis AI, McGrath SJ, et al. Improving women’s cardiovascular health: a position statement from the International Council on Women’s Health Issues. Health Care Women Int. 2012;33(10):943‐955. doi:10.1080/07399332.2011.646375

- Mosca L, Jones WK, King KB, et al. Awareness, perception, and knowledge of heart disease risk and prevention among women in the United States. American Heart Association Women’s Heart Disease and Stroke Campaign Task Force. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(6):506–515. doi:10.1001/archfami.9.6.50610862212

- Marcuccio E, Loving N, Bennett SK, Hayes SN. A survey of attitudes and experiences of women with heart disease. Womens Health Issues. 2003;13(1):23–31. doi:10.1016/S1049-3867(02)00193-712598056

- Mosca L, Hammond G, Mochari-Greenberger H, et al. American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in Women and Special Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on High Bloo. Fifteen-year trends in awareness of heart disease in women: results of a 2012 American Heart Association national survey. Circulation. 2013;127(11):1254–1263.23429926

- Khan NA, Daskalopoulou SS, Karp I, et al. GENESIS PRAXY Team. Sex differences in acute coronary syndrome symptom presentation in young patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1863–1871.24043208

- Lichtman JH, Leifheit EC, Safdar B, et al. Sex differences in the presentation and perception of symptoms among young patients with myocardial infarction: evidence from the VIRGO Study (Variation in Recovery: role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI Patients). Circulation. 2018;137(8):781–790. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.03165029459463

- Mosca L, Linfante AH, Benjamin EJ, et al. National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines. Circulation. 2005;111(4):499–510. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000154568.43333.8215687140

- Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(8):618–626. doi:10.1056/NEJM19990225340080610029647

- Mosca L, Hammond G, Mochari-Greenberger H, et al. American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in Women and Special Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on High Bloo. Fifteen-year trends in awareness of heart disease in women: results of a 2012 American Heart Association national survey. Circulation. 2013;127(11):1254–1263.23429926

- Karwalajtys T, Kaczorowski J. An integrated approach to preventing cardiovascular disease: community-based approaches, health system initiatives, and public health policy. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2010;3:39‐48.