?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

An intervention to reduce insecticide exposure in Shogun orange farmers was implemented in Krabi Province, Thailand. Intervention effects on insecticide-related knowledge and attitude were evaluated in a quasi-experimental study in two farms about 20 kilometers (km) apart. The intervention was conducted at one farm; the other served as control. The study included 42 and 50 farmers at the intervention and control farms, respectively. The intervention included several components, including didactic instruction, practical demonstrations, use of a fluorescent tracer, and continuing guidance on insecticide use via a small, specially trained group within the overall intervention group. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first such intervention in Thailand. Knowledge and attitude were measured at baseline (pre-intervention), and at 2 and 5 months after the intervention (follow-up 1 and follow-up 2, respectively). Intervention effects were assessed with linear mixed models, specified to enable testing of effects at each follow-up time. The intervention was associated with substantial and statistically significant improvements in both knowledge score and attitude score (P < 0.001 for each score at each follow-up time). Intervention-related improvements in knowledge score and attitude score were equivalent to about 27% and 14% of baseline mean knowledge and attitude scores, respectively. Intervention-related benefits were similar at both follow-up times. Findings were similar before and after adjustment for covariates. These findings increase confidence that well-designed interventions can reduce farmers’ insecticide exposure in Thailand and elsewhere. In future research, it would be desirable to address long-term intervention effects on farmers’ health and quality of life.

Introduction

Exposure to insecticides through consumption of fruits is widespread. Fruits are often subjected to pre- and post-harvest treatment with insecticides, particularly organophosphates, carbamates, and pyrethroids.Citation1 Citrus fruit crops like mandarin oranges, Shogun oranges, lemons, and pomelo are grown in many regions of Thailand. The insect pests that commonly affect citrus crops in Thailand include 23 species in six orders – Thysanoptera, Homoptera, Hemiptera, Coleoptera, Lepidoptera, and Diptera. Specific pests vary according to the kind of citrus fruit and area of cultivation.Citation2 Citrus growers regularly use chemicals to control pests. Repeated usage can cause resistance, leading to increased pesticide use, and quite possibly increased health risk.

Shogun oranges (Citrus sinensis [L.] Osbeck) are an important product in the royally sponsored One Tumbol One Product (OTOP) project in Krabi Province. In the Khao-phanom District of Krabi, 80% of the plantation area was used to produce Shogun oranges. In the year 2000, the surveillance report from the province showed that people from this region were getting ill from their occupation.Citation3 According to the Epidemiological Surveillance Report released by the Department of Epidemiology, occupation-related illness was seen in 4,337 patients and insecticide-related poisoning was the cause in 71.68% of nationwide cases.Citation3 The 2001 Fiscal Year Report by the Department of Sanitation reported that there were 21 deaths due to pesticide poisoning and the morbidity ratio from pesticide poisoning was 15.43:100,000.Citation4 In 2001–2002, there were two patients with pesticide poisoning in Krabi ProvinceCitation4 and 13 patients among Shogun orange farmers in Khao-phanom District.Citation5 In 2011, the report ‘Healthy Farmers and Safety Consumers’, from the Public Health Office in Krabi Province showed unsafe levels of serum cholinesterase;Citation6 farmers were screened for serum cholinesterase levels by reactive paper finger-blood test. Out of 743 Krabi farmers screened, 204 (27.46%) had unsafe cholinesterase levels.Citation6 These reports suggest that the farmers are at risk of both short-term and long-term health impairment due to exposure to insecticides.

In recent years, though there have been efforts to improve food safety and improve public health of both the farmers and consumers, insecticide use remains high. The health risks to the farmers (high use) and health risks to consumers (due to high residue levels in the produce) are important public health problems. To develop effective solutions for this, improvements in farmers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding insecticide use are necessary.

To address these issues, we conducted a quasi-experimental study to implement and evaluate an intervention aimed at reducing insecticide exposure in Shogun orange farmers in Krabi Province. The effects of the intervention on insecticide-related knowledge and attitude are reported here. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first intervention targeted specifically at reducing insecticide exposure in Thai farmers.

Methods

Study population

This quasi-experimental study was conducted on 92 Shogun orange farmersCitation7 in Khao-Phanom District, Krabi Province. Two farms, about 20 km apart, were selected for the study. The intervention was conducted in one farm; the other farm served as the control area. The intervention and control groups consisted of 42 and 50 adults, respectively (see ). The study was conducted from April 2012 to November 2012. All participants signed an informed consent form. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the College of Public Health Sciences, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand (COA No. 256/2555).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics compared between the intervention group and control group: continuous independent variables

Procedures

Both farms had a single owner, and cultivation practices and pesticide usage were very similar at both. In the study area, Shogun oranges are grown, and agricultural pesticides are used throughout the year – there are no distinct cultivation cycles as in rice farming. The required sample size was calculated based on a previous studyCitation8 to detect differences with confidence = 95% and power = 80%, using the OpenEpi program (v2). Though the sample size thus calculated was 68, we included 92 participants to accommodate missing data and possible dropouts. Data were collected by a team of eight persons, which included health officers and researchers from the district.

The data collection instrument was a standardized, interviewer-administered questionnaire adapted from the Agricultural Health Study in the USCitation9 (2010) and local studies.Citation8,Citation10 The questionnaire queried: (1) sociodemographic characteristics – sex, age, education, smoking history, drinking alcohol, health status, work characteristics, duration of work, and types and durations of use of insecticides and other pesticides; (2) knowledge regarding insecticide as assessed by 15 close-ended questions; (3) attitude regarding insecticide use as assessed by 26 questions. For each knowledge question, respondents received one point and zero points for a correct and incorrect answer, respectively (total possible knowledge score ranged from 0–15). For each attitude question, respondents checked one choice on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. The score for each attitude question ranged from 5 for best attitude to 1 for worst attitude (total possible attitude score ranged from 26–130). The knowledge questions and attitude questions are shown in the appendix. The questionnaire was validated with pilot testing for clarity and reliability on 30 Shogun farmers in Prasang District, Suratthani Province, by the first author. Pilot testing showed good reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.881.

Questions on sociodemographic characteristics (independent variables) were administered at baseline, before the intervention. Questions on knowledge and attitude (dependent variables) were administered at baseline, at 2 months after the intervention (follow-up 1), and at 5 months after the intervention (follow-up 2).

The intervention program lasted for 4 days, and drew upon the principles of Social Cognitive Theory.Citation11–Citation15 The first 2 days consisted of training in insecticide-related knowledge. The first day covered pesticide utilization and problems in Thailand, types of pesticides, classification and hazard, routes of exposure, impact of pesticides on health and environment, and pesticide-related symptoms. The second day covered information on pesticide labels, guidelines for safe use, protective behaviors, appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), first aid for poisoning, and patient transfer to medical care. The last 2 days consisted of practical training.

Day 3 covered demonstrations using a fluorescent tracer,Citation16 use of a baseball cap as an example of partial but suboptimal PPE, unplugging a spray nozzle, dirty fruits and vegetables, handshake, improper removal of PPE, inappropriate practice regarding cell phones and smoking, and pesticide formulations. The fluorescent tracer is used to mark areas where pesticides get on skin and clothes. Unlike pesticides, the tracer glows under a black light, and thus shows that areas can be contaminated even though the contamination is invisible. Day 4 covered actual applications as done in normal practice, with the fluorescent tracer added to the pesticides.

The intervention also included special training of ten persons in the intervention group, whom their peers had identified as highly respected. This ‘model group’ was available to advise intervention group members regarding insecticide use throughout the study.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe means, frequencies, percentages, and standard deviations for sociodemographic characteristics, and for knowledge and attitude scores. Baseline differences in independent variables between the intervention and control groups were tested by the Chi-square test and independent samples t-test for dichotomous and continuous variables, respectively.

At any follow-up time, the magnitude of the intervention effect is the difference between the intervention and control groups in the change in mean score from baseline to follow-up. This is given in the expression below.

We constructed linear mixed models to quantify and test the statistical significance of intervention effects on knowledge and attitude scores at each follow-up time. Unadjusted fixed-effects models included the main effects of intervention and each follow-up time, and an intervention–time interaction term for each follow-up time. In these models, the coefficients of the interaction terms were equal to the intervention effects, as described above at the two follow-up times. Each model included a ‘repeated’ statement, with time as the repeated measure, the study participant as the individual subject, and with an unstructured covariance type. In separate models, intervention effects were adjusted for personal chronic illness history, use of mosquito coils, and spraying pesticides in the home (see below for explanation of this adjustment). P-values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. Intervention effects were reported as absolute magnitudes and as percentages of baseline mean scores.

The overall association between knowledge score and attitude score was evaluated with an additional mixed model with the attitude score as the dependent variable and the knowledge score as the independent variable. This model also included a ‘repeated’ statement for time, with an unstructured covariance type. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (v16; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Continuous and categorical independent variables are summarized and compared between the intervention and control groups in and , respectively. Prevalences of positive personal illness history, burning mosquito coils, and spraying pesticides in the home were statistically significantly higher in the intervention group than the control group (). Thus, intervention effects on knowledge and attitude scores were adjusted for these characteristics. No other baseline characteristics differed significantly between the study groups (P ≥ 0.104), so no adjustment was made for these other characteristics.

Table 2 Baseline characteristics compared between the intervention group and control group: categorical independent variables

Unadjusted intervention effects, at follow-up 1 and follow-up 2, are shown in . The intervention was associated with substantial and statistically significant improvement in both knowledge score and attitude score at both times (P < 0.001) for both scores for both follow-up times. For example, from baseline to follow-up 1, knowledge score increased by 2.9 points more in the intervention group than the control group. This represented an intervention-related improvement equal to 26.4% of the baseline mean knowledge score. Absolute intervention effects on attitude score were larger than on knowledge score, although proportional improvements in the former were smaller than in the latter. For each score, intervention-related benefits were similar at both follow-up times.

Table 3 Absolute magnitudes of unadjusted intervention effects on knowledge score and attitude score, and intervention effects as percentages of baseline mean scores, at follow-up 1 and follow-up 2

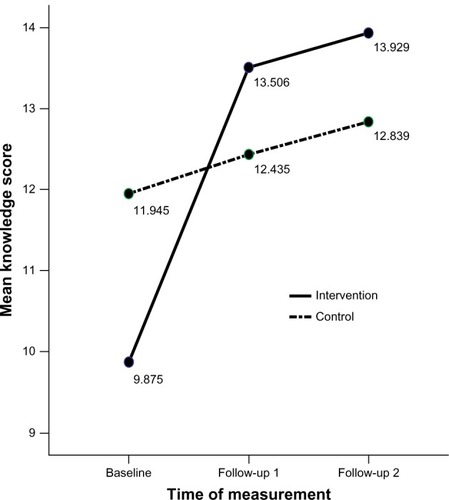

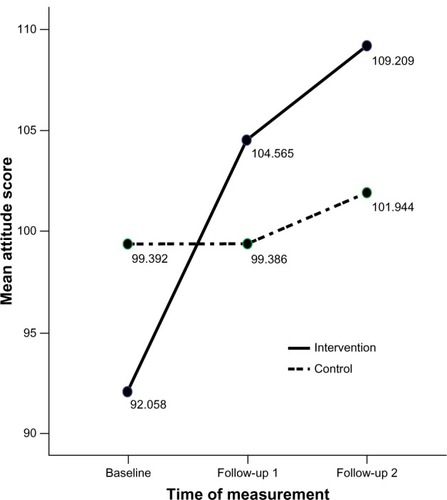

Adjusted mean knowledge scores in the intervention and control groups, at the three measurement times, are shown in . Adjusted mean attitude scores are shown in . The figures show that increases in both scores from baseline to follow-up were greater in the intervention group. This indicates a beneficial effect of the intervention on both scores. Adjusted intervention effects are shown in . Adjusted intervention effects, like unadjusted ones, were consistently beneficial and statistically significant (P < 0.001). A comparison of and shows that adjustment made little difference in modeled benefits of intervention, expressed as both absolute magnitude and as a percentage of the baseline mean score.

Figure 1 Adjusted mean knowledge scores in the intervention and control groups at baseline, follow-up 1, and follow-up 2. Scores were adjusted for positive chronic illness history, burning mosquito coils, and spraying pesticides in the home.

Figure 2 Adjusted mean attitude scores in the intervention and control groups at baseline, follow-up 1, and follow-up 2. Scores were adjusted for positive chronic illness history, burning mosquito coils, and spraying pesticides in the home.

Table 4 Absolute magnitudes of adjustedTable Footnote* intervention effects on knowledge score and attitude score, and intervention effects as percentages of baseline mean scores, at follow-up 1 and follow-up 2

The overall relationship between knowledge score and attitude score is shown in . There was a strong and statistically significant positive relationship between the two scores. Specifically, the modeled attitude score increased by 2.29 points for each one-point increase in knowledge score (P < 0.001).

Table 5 Relationship between insecticide-related attitude score and knowledge score in study participants over all three measurement times

Discussion

This quasi-experimental study was designed to measure and assess the effects of a novel intervention, intended to reduce insecticide exposure in Shogun orange farmers in Krabi Province, Thailand. The intervention was associated with substantial and statistically significant improvements in knowledge and attitude related to insecticide use. Our findings increase confidence that well-designed, targeted interventions can be effective in reducing farmers’ exposure to insecticides in Thailand and possibly elsewhere.

As mentioned above, the intervention incorporated several components, including didactic instruction, practical demonstrations, use of a fluorescent tracer, and provision of continuing guidance regarding proper insecticide use via a specially trained model group within the overall intervention group. The study design did not enable comparative testing of the specific contributions of these components to the overall effects of the intervention. It would be desirable to address this topic in future research.

The intervention in this study was targeted specifically toward reducing insecticide exposure. Farmers in the study area and elsewhere use a wide variety of pesticides in addition to insecticides. It is quite conceivable that broader interventions, intended to reduce exposure to both insecticides and other pesticides, may be associated with larger benefits than were observed in this study. Such broader interventions should be implemented and evaluated in further research. Finally, the ultimate goal of pesticide-related agricultural interventions is to improve farmers’ health and quality of life. Assessing such long-term goals was beyond the scope of the present study. Hopefully, it will be possible to conduct long-term research in the future, in which the effectiveness of interventions in achieving these goals can be assessed.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere thanks go to Dr Peerapon Rattana and Dr Wattasit Siriwong for their valuable suggestions. We also wish to thank health officers at the Khao-phanom Health Office and the District Health Office in Krabi Province. We acknowledge the Chulalongkorn University 90th year scholarship program (Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund) and the Thai Fogarty ITREOH Center, Chulalongkorn University. Special thanks to the Shogun orange farmers for their kind support throughout the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- RawnDFRoscoeVKrakalovichTHansonCN-methyl carbamate concentrations and dietary intake estimates for apple and grape juices available on the retail market in CanadaFood Addit Contam200421655556315204533

- AhunhawuthiCThe Insect Pests in Citrus FruitsJarernrat PressBangkok1999

- Department of EpidemiologyThe Epidemiological Surveillance ReportThe MinistryBangkok2000

- Department of SanitationThe Fiscal Year ReportThe MinistryBangkok2001

- Krabi Provincial Health OfficeThe Epidemiological Surveillance ReportKrabi Provincial Health OfficeKrabi2002

- Krabi Provincial Health OfficeThe Healthy Farmers and Safety Consumers ReportKrabi Provincial Health OfficeKrabi2011

- Krabi Agriculture OfficeThe Data in Product of Shogun Orange Plantations in Krabi ProvinceKrabi Agriculture OfficeKrabi2009 Available from: http://www.krabi.go.th/impor/plant53.xlsAccessed February 5, 2011

- SoratWThe Relationship Between Health Belief, Pesticide Use and Safety Behaviors with Acute Poisoning Symptom of Farmers, Chaiyaphom Province [master’s thesis]Nakhon PathomMahidol University2004

- Agricultural Health StudyFull Text of QuestionnairesAgricultural Health Study2010 [updated July 2013]. Available from: http://aghealth.nih.gov/background/questionnaires.htmlAccessed August 28, 2013

- BoonyakaweePHealth Effects of Pesticides Use in Agriculturists at Krabi-noi Sub-District, Maung District, Krabi Province [master’s thesis]BangkokChulalongkorn University2007

- BanduraASocial Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive TheoryEnglewood Cliffs, NJPrentice Hall1986

- BanduraAHealth promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theoryPsychol Health199813623649

- BanduraASocial cognitive theory of mass communicationsBryantJZillmanDMedia Effects: Advances in Theory and ResearchHillsdale, NJErlbaum2002

- BanduraAHealth promotion by social cognitive meansHealth Educ Behav20043114316415090118

- McAlisterALPerryCLParcelGSModels of interpersonal health behavior How Individuals, Environments, and Health Behaviors Interact: Social Cognitive TheoryGlanzKRimerBKViswanathKHealth Behavior and Health EducationJossey-BassSan Francisco2008169185

- University of Washington Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center (PNASH)Fluorescent Tracer Manual: An Educational Tool for Pesticide Safety EducatorsPNASHSeattle2007

Appendices

Appendix A – Knowledge on insecticide use in study participants (15 questions total)

Check only one choice in each question. (Correct answers are checked below. Correct answers received one point. Incorrect answers received zero points. Minimum and maximum possible total scores are 0 and 15, respectively.)

Appendix B – Attitude of participants toward insecticide use (26 questions total)

Check only one choice for each question. (Positive-direction questions were scored from 5 points for ‘strongly agree’ to 1 point for ‘strongly disagree’. Negative-direction questions were scored from 1 point for ‘strongly agree’ to 5 points for ‘strongly disagree’. Minimum and maximum possible total scores are 26 and 130, respectively.)