Abstract

Pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) in patients with bladder cancer varies widely in extent, technique employed, and pathological workup of specimens. The present paper provides an overview of the existing evidence regarding the effectiveness of PLND and elucidates the interactions between patient, surgeon, pathologist, and treating institution as well as their cumulative impact on the final postoperative lymph node (LN) staging. Bladder cancer patients undergoing radical cystectomy with extended PLND appear to have better oncologic outcomes compared to patients undergoing radical cystectomy and limited PLND. Attempts have been made to define and assess the quality of PLND according to the number of lymph nodes identified. However, lymph node counts depend on multiple factors such as patient characteristics, surgical template, pathological workup, and institutional policies; hence, meticulous PLND within a defined and uniformly applied extended template appears to be a better assurance of quality than absolute lymph node counts. Nevertheless, the prognosis of the patients can be partially predicted with findings from the histopathological evaluation of the PLND specimen, such as the number of positive lymph nodes, extracapsular extension, and size of the largest LN metastases. Therefore, particular prognostic parameters should be addressed within the pathological report to guide the urologist in terms of patient counseling.

Introduction

In the early cystectomy era, the prognosis of patients with lymph node (LN) metastases was thought to be uniformly bleak. The value of meticulous LN dissection for patients undergoing radical cystectomy (RC) for muscle-invasive bladder cancer was first demonstrated in 1982 when SkinnerCitation1 showed that cure is possible even in patients with LN metastases following RC and concomitant pelvic LN dissection (PLND). In that series, PLND provided better local control without adding substantially to morbidity. Additionally, postoperative histologic LN staging allowed identification of patients at risk who could be directed to adjuvant therapies. Despite this early description, no prospective randomized trials have yet been finalized to test this concept. Nevertheless, the necessity of PLND within the context of RC is generally accepted, and the majority of oncologic urologists perform at least some form of PLND. The present paper provides an overview of the existing evidence regarding the effectiveness of PLND and elucidates the interactions between patient, surgeon, pathologist, and treating institution, as well as their cumulative impact on the final postoperative LN staging.

Bladder cancer surgery and natural course of the disease

Simple cystectomy without PLND was an early surgical approach to treating patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. However, its survival rates were frustrating.Citation2 Urologists later experimented with expanded dissection areas and found that extended dissections were feasible from both the technical and perioperative mortality standpoints.Citation3–Citation8 However, the perioperative mortality could be considerable, as illustrated by a case series reported mid-20th century; although there were no intraoperative deaths, five of the 22 patients died within the first 2 postoperative weeks.Citation5

In 1950, Leadbetter and CooperCitation6 were the first to describe the surgical principles of RC before Marshall and WhitmoreCitation9 substantiated the procedure 6 years later. Nowadays, RC represents a standard intervention with a 1%–2% rate of perioperative deaths in experienced centers.Citation10

Of all patients diagnosed with bladder cancer, 20%– 40% initially present with muscle-invasive disease. For those undergoing RC with PLND, postoperative tumor stage and LN status are important predictors of outcome. The rate of LN metastasis is associated with the primary tumor stage, and increases from 5%–10% in non-muscle-invasive bladder tumors (pT0, pTa, pTis, pT1), to 18% in superficial muscle-invasive tumors (pT2a), to 27% in deep muscle-invasive tumors (pT2b), and to 45% in extravesical tumors (pT3-4). Accordingly, LN-negative pT0, pTa, and pT1 patients have the best outcomes, with recurrence-free rates at 5 years and 10 years of >90%.Citation11 The recurrence-free rates for patients with pT2 pN0-N2 tumors are around 75% and 70% at 5 years and 10 years, respectively. The rates decrease to 45%–50% at 5 years and 45% at 10 years for patients with pT3 pN0-N2 tumors.Citation12 Due to the various sites of local invasion, pT4 tumor patients represent a heterogeneous cohort with recurrence-free rates around 45% and 35% at 5 years and 10 years, respectively.Citation11,Citation13,Citation14 In general, progression following radical surgery is associated with a dismal prognosis and usually occurs within the first 2 years. Overall, survival following radical surgery alone remains modest at 43%–57%. It is the patient with an organ-confined primary tumor (<pT3) and limited LN involvementCitation15 that has the best chance for long-term cure. In contrast, patients with intraoperative grossly LN-positive disease have even a 25% chance of cure following radical surgery with extended PLND.Citation16

Pelvic lymph node dissection – ongoing controversies

The main controversy regarding PLND is related to the optimal extent of PLND. The fact that the prognostic and therapeutic benefits of PLND are based on retrospective cohort studiesCitation12,Citation17–Citation20 explains the lack of consensus in this matter. It is hoped that two ongoing prospective randomized trials (the SWOG trial S1011Citation21 and the German multicenter study LEACitation22) will soon be able to elucidate this important problem and provide the necessary information to define a “standard” oncologic template for PLND. The variety of PLND templates currently applied makes outcome comparisons difficult.

In addition to the template problem, numerous attempts have been made to define the proper extent of PLND based on the number of LNs identified, and to determine the prognostic value of LN density. These topics will be discussed with reference to the inherent connection between patient, surgeon, pathologist, and the treating institution.

Pelvic lymph node dissection – fundamental considerations

The physiology of lymphatic drainage of the urinary bladder is complex. Applying their technetium-based mapping study, Roth et alCitation23 identified not fewer than 24 primary lymphatic landing sites per urinary bladder. Of these, only 8%–10% were detected proximal to the mid-upper third of the common iliac vessels. Moreover, no radioactive solitary extra pelvic LNs (skip lesions) were identified. Focusing on the small pelvis, one-fourth of the primary lymphatic landing sites were located in the internal iliac region, with almost half (42%) of them lying medial to the internal iliac artery.Citation23 In terms of laterality, following strictly unilateral technetium injection, at least one primary lymphatic landing site was found on the ipsilateral side and 40% of patients had at least one additional primary lymphatic landing site on the contralateral side.Citation24 This underscores the necessity of bilateral PLND in all cystectomy patients.

Prior to the technetium-based analyses, conventional LN mapping studies provided important information regarding common sites of pelvic LN metastases.Citation25–Citation27 However, these studies had considerable limitations, such as overlapping dissection areas and the substantial reliance of intraoperative labeling on the surgeon’s discretion.

Fundamentally, any analysis of lymphatic tissue based on the tissue specimen removed involves an inherent bias; it remains unknown how much tissue/how many LNs were left behind. As a consequence, the reliable definition of an adequate PLND based on postoperative pathologic findings or number of LNs removed/identified is not feasible. A possible approach would be to develop an imaging technology that can identify lymphatic tissue left in situ after RC and PLND.

The patient

Physiologically, there exist considerable interindividual differences in terms of LN counts. Weingärtner et alCitation28 identified a mean of 22.7 ± 10.2 pelvic LNs per patient in their autopsy series (n = 30) with a wide range of eight to 56 LNs. In another recent cadaver study, the range of identified pelvic lymph nodes was high (19–53 LNs), even with evaluation by a single pathologist.Citation29 In our intra-institutional analysis including oncologic outcomes we found a similarly wide range of LNs per patient (eight to 55 LNs) without an impact on survival.Citation30,Citation31 More recently, Mitra et alCitation32 demonstrated that patient characteristics such as age, body mass index, clinical tumor stage, type of tumor growth, multifocality, and surgical margins can substantially influence total nodal yields. Therefore, interindividual variation is an important factor affecting the number of identified LNs in the context of PLND.

The surgeon

Since the surgeon decides upon the performance, extent, and quality of a PLND, he/she may be a key factor for success. Nevertheless, in a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program database analysis capturing approximately one-fourth of the US population, 40% of all patients (n = 1,923) undergoing RC between 1988 and 1998 did not have a PLND.Citation33 Hollenbeck et alCitation34 demonstrated in a similar more resent study (n = 3,603) that the majority of cystectomy patients had only a few pelvic LNs (≤4 LNs) removed at the time of RC, irrespective of hospital volumes. In contrast, the rate of patients with ≥10 LNs decreased from 35.3%, to 12.7%, to 0% when comparing hospitals with high, medium, and low LN counts, respectively. Furthermore, high-volume hospitals achieved a more even distribution of LN counts.

Without doubt, PLND is performed near to delicate anatomic structures and is time consuming. On the other hand, a meticulous PLND helps to identify pelvic structures, facilitates cystectomy, and offers better vascular controlCitation35 without increasing perioperative morbidity.Citation27,Citation36 It is difficult to estimate the impact of surgical education/experience, institutional philosophy, and possible economic considerations (reimbursement) on the extent and thoroughness of PLND. Nevertheless, these factors may explain, to some extent, the differences in practice among urologists.

A critical issue for the surgeon is whether to adopt a new surgical approach, eg, whether to switch from open to minimally invasive RC. While it has been shown that even a super-extended PLND is feasible and safe with robotic assistance,Citation37 PLND is often omitted in the initial phase of the procedural learning curve.Citation38 The performance of an extended PLND is significantly associated with institutional and individual surgeons’ case number and surgical volume.Citation9 However, urothelial cancer does not allow any oncologic compromise and requires a thorough extended PLND, irrespective of surgical approach.

The pathologist

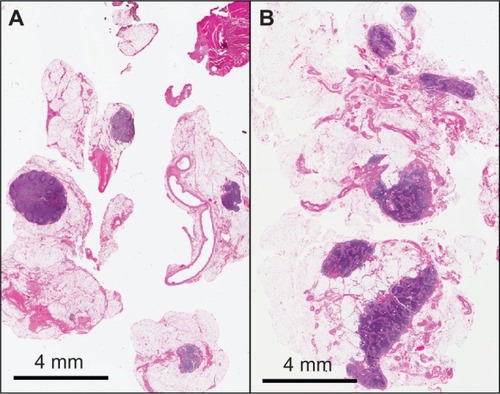

Because pathology findings are greatly impacted by the specific local tissue workup process, several factors have to be considered when comparing pathology reports on LN specimens from various institutions.Citation39 First, the submission of specimens in separate packets instead of en bloc significantly increases the number of reported LNs.Citation40 The use of smaller specimens might facilitate macroscopic identification of LNs by the pathologist and may also allow for better fixation and processing,Citation41 thus improving the detection of LNs. Second, the use of certain fixation and processing methods, eg, acetone or Carnoy’s solution, results in resolution of fatty tissue and enhances the macroscopic visibility of LNs,Citation42 facilitating identification of LNs and potentially increasing nodal counts. Third, the more meticulous the pathologist’s examination of the specimens, the greater the number of LNs identified. Moreover, the more accurate the pathologist’s report on the embedding of nodes, the easier the counting of LNs under the microscope ().Citation43 Fourth, and a rarely reported factor, the amount of tissue that is embedded for microscopic examination affects LN yield; embedding the entire specimen, for example, increases the number of nodes identified.Citation42 According to personal, unpublished data (2009), approximately two additional nodes are found per packet in the remaining, not routinely embedded lymphadenectomy tissue. Fifth, although the histological criteria defining LNs are clearly established, the determination of a LN in a microscopic slide not only depends on the sectional plane through the LN, but also varies between pathological institutes and pathologists.Citation43 Parkash et alCitation43 evaluated LN counts on slide scans performed by ten pathologists, each pathologist receiving the same series of slides for review. They noted considerable interobserver and intra-observer variability, which was particularly dependent on the macroscopic description of the slide given by the study coordinator.

Figure 1 Images of two histopathological lymph node slides.

Finally, molecular staging techniques, such as reverse transcription real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), have been investigated to determine whether they can detect the presence of missed micrometastases in LNs during routine pathological workup. RT-qPCR has been applied in breast,Citation44 colon,Citation45 and urinary bladder cancersCitation46,Citation47 to detect small changes in gene expression (eg, CK-19, CK10, or Uroplakin II) indicative of micrometastases or disseminated cancer cells. In line with findings on other neoplasias, the detection of micrometastases in bladder cancer is increased by RT-qPCR,Citation46,Citation47 and is linked to unfavorable tumor characteristicsCitation47 and even associated with adverse outcomes.Citation46 However, in bladder cancer, the true clinical impact of these molecular micrometastases remains largely unknown and external validation of these data is urgently needed. Therefore, these techniques are not routinely used.

Another evaluated molecular technique is keratin immunohistochemistry (keratin IHC). In breast cancer, keratin IHC appears to increase the detection of occult micrometastases, particularly in sentinel LNs.Citation48 However, the sentinel LN hypothesis is not a reliable concept in bladder cancer patients due to the high rate of false negative nodes.Citation49 Furthermore, it has been shown that keratin IHC does not detect additional micrometastases within a complete lymphadenectomy specimen.Citation50 As a consequence, investigation of keratin IHC is no longer being investigated.

In bladder cancer patients, neoadjuvant chemotherapy significantly improves survival,Citation51,Citation52 which in future might shift the paradigm towards a routinely administered neoadjuvant chemotherapy.Citation53 The challenge for the pathologist will then be to define prognostic and predictive features in medically pretreated surgical specimens. The number of evaluated lymph nodes in lymphadenectomy specimens after neoadjuvant chemotherapy seems to be virtually the same compared to treatment naïve specimens.Citation54 However, as in rectalCitation55,Citation56 and esophagealCitation57–Citation59 cancers, tumor regression grades, which are thought to quantify the histopathological extent of tumor response to chemotherapy, have shown stronger prognostic impact in bladder cancers than the classification of malignant tumors (yTNM) stages.Citation54 Consequently, pathologists should start to report and urologists should become accustomed to these pathologic alterations in order to better interpret patient outcomes.

The treating institution

With increasing numbers of RCs performed using robotic assistance, interesting data are emerging regarding the impact of surgical experience on the performance of PLND. The International Robotic Cystectomy Consortium has demonstrated that the performance, extent, and thoroughness of robotic-assisted surgery are affected by both individual surgical volumes and institutional case volumes.Citation9

Additionally, it is not solely the surgeon’s personal experience and preference, but also the institutional philosophy that decide on the choice of template applied at RC. The surgical template impacts patient outcome, as demonstrated in two consecutive observational studiesCitation12,Citation17 evaluating three differing PLND templates from three cystectomy centers. Dhar et alCitation17 compared the oncologic outcomes of patients undergoing RC with limited PLND to that of patients undergoing RC with extended PLND. With an extended PLND up to the mid-upper third of the common iliac vessels instead of a limited PLND only, the rate of LN-positive patients doubled. This indicates the substantial under-staging of patients undergoing limited PLND. Furthermore, the application of extended PLND resulted in a significantly better 5-year recurrence-free survival, irrespective of the final pathologic LN status. The removal of all lymphatic tissue up to the inferior mesenteric artery does not confer an additional survival benefit, as shown with the subsequent template comparison.Citation12

Fang et alCitation60 demonstrated the effect of a policy requiring identification of a minimum number of LNs. According to this policy, any lymphadenectomy specimen with fewer than 16 LNs was resubmitted to a senior pathologist for review. As a consequence, the median number of LNs identified per patient increased by five, and the rate of specimens with more than 16 LNs almost doubled from 43% to 70%.

Postoperative lymph node staging

Despite improved imaging technology, PLND remains the most accurate and reliable approach to staging LNs in bladder cancer patients. Different parameters have been investigated in lymphadenectomy specimens in terms of their prognostic value, such as number of identified and positive LNs, LN density, the diameter of the largest metastasis, and the extracapsular extension of LN metastases.

MulticenterCitation61–Citation63 and single institution studiesCitation18,Citation20 have shown that a higher number of identified LNs can be associated with better outcomes. However, as discussed above, the number of LNs varies substantially between institutions. This must be taken into account when numbers of identified LNs are evaluated in terms of a generally applicable prognostic tool. If, in single institution series, the outcomes of patients analyzed according to interquartile LN ranges is virtually identical, variations of LN counts might depend more on individual physiological variations and procedural (histological workup) differences and could reflect the uniformity of the lymphadenectomy performed in this cohort.Citation30 Thus, analysis of interquartile ranges of LN counts for survival might serve as an institutional quality control for lymphadenectomy. As such, total LN yield is a problematic measure of dissection extent or oncologic quality. This was demonstrated by Dorin et al,Citation64 who compared LN counts between two cystectomy centers, applying the same PLND template. Despite differing median LN counts (40 versus 72 LNs), neither the proportion of LN-positive patients nor the oncologic outcomes of the two cohorts were found to be different. The authors concluded that the applied PLND template is more important than total LN yield.

Different investigators have proposed LN density (ratio of positive and identified nodes) as a prognosticator of survival.Citation15,Citation65,Citation66 In various series,Citation15,Citation65,Citation66 LN density predicted survival in univariate analyses. In contrast, multivariable confirmation was only achieved in few studies.Citation15 LN density is not only a function of nodal tumor burden and extent or quality of lymphadenectomy, but also of the natural variation in the number of pelvic LNs and differences in pathological workup. Therefore, this concept is of questionable value. Similar to total LN yield, LN density depends substantially on institutional standards. Hence, categorical LN densities used to risk stratify patients for counseling regarding prognosis may be useful on an institutional level,Citation67 but any interinstitutional comparison will be difficult.

The size of the largest LN metastasis is a prognostic factor in different cancersCitation68–Citation70 and, according to the 7th TNM classification, determines postoperative LN (pN) stages in head and neck, as well as in gynecological cancers.Citation71 In bladder cancer, however, the diameter of the largest LN metastasis is not an independent risk factor and therefore is not included in the current 7th TNM classification.

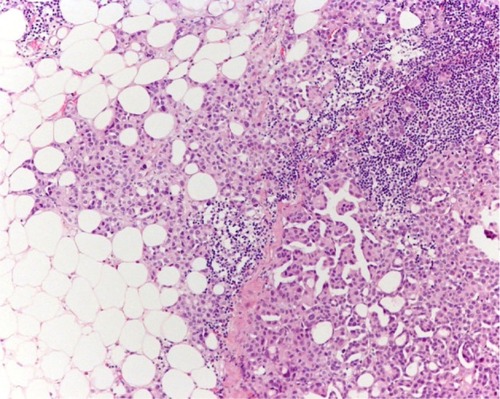

The prognostic relevance of extracapsular extension (ECE) in patients with LN metastases () has been evaluated in five single center cohortsCitation30,Citation72–Citation76 and one multicenter analysisCitation77 with divergent results. ECE was the strongest independent adverse risk factor in our own cohort.Citation30,Citation75 Poor outcomes of patients with ECE was also noted in other series.Citation72–Citation74,Citation76 However, in the study of Frank et al,Citation72 ECE was found not to be an independent risk factor in patients after limited PLND, while the study of Jeong et alCitation73 reported a low frequency of ECE. Conversely, ECE was not a prognosticator in the MD Anderson cohort,Citation74 but the information on ECE was based on pathology records instead of a slide review. Similarly, Stephenson et alCitation76 could not detect a prognostic impact. Finally, ECE was identified as an independent unfavorable parameter for cancer recurrence and death in a recently published multicenter retrospective study.Citation77 Unfortunately, in that study, PLND was not uniformly performed and a central pathologic review of all slides was not performed. Taken together, the substantial differences between cohorts and methods existing between the aforementioned studies might have contributed to the conflicting results.

Figure 2 Extracapsular extension of lymph node metastases.

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) is another prognostic factor in the assessment of bladder cancer. LVI is particularly investigated in cystectomy and transurethral resection specimens of primary tumors,Citation78,Citation79 and only Fritsche et alCitation80 evaluated the prognostic impact of perinodal LVI in PLND specimens. Although the latter multicenter study lacks a complete pathological review, perinodal LVI was found to be an independent risk factor for early cancer-related death. Therefore, this parameter should be routinely reported in the final pathological report.

Conclusion

The optimal extent of PLND in bladder cancer is still under debate. Based on the present analysis of retrospective cohort studies, meticulous extended PLND to the mid-upper third of the common iliac vessels should be the standard of care for patients with high risk non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive bladder cancer. By reporting the number of LNs identified, we outline the lymphatic tissue that has been removed; however, the lymphatic tissue that has been left behind may be responsible for cancer recurrence and remains unquantified. Moreover, LN counts depend on multiple factors such as patient, surgeon, pathologist, and institution, and consequently are not the best markers of the quality of a PLND. Nevertheless, some histopathological parameters resulting from the pathological workup help to better predict patient outcomes.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SkinnerDGManagement of invasive bladder cancer: a meticulous pelvic node dissection can make a differenceJ Urol1982128134367109065

- BriceMIIMarshallVFGreenJLWhitmoreWFJrSimple total cystectomy for carcinoma of the urinary bladder; one hundred fifty-six consecutive cases five years laterCancer19569357658413330011

- ApplebyLHProctocystectomy; the management of colostomy with ureteral transplantsAm J Surg1950791576015399353

- BrickerEMModlinJThe role of pelvic evisceration in surgerySurgery1951301769414845996

- BrunschwigAComplete excision of pelvic viscera for advanced carcinoma; a one-stage abdominoperineal operation with end colostomy and bilateral ureteral implantation into the colon above the colostomyCancer19481217718318875031

- LeadbetterWFCooperJFRegional gland dissection for carcinoma of the bladder; a technique for one-stage cystectomy, gland dissection, and bilateral uretero-enterostomyJ Urol195063224226015403829

- ParsonsLLeadbetterWFUrologic aspects of radical pelvic surgeryN Eng J Med195024220774779

- WhitmoreWFJrMarshallVFRadical total cystectomy for cancer of the bladder: 230 consecutive cases five years laterJ Urol19628785386814006639

- MarshallVFWhitmoreWFJrThe present position of radical cystectomy in the surgical management of carcinoma of the urinary bladderJ Urol195676438739113368292

- QuekMLSteinJPDaneshmandSA critical analysis of perioperative mortality from radical cystectomyJ Urol200617588688916469572

- HautmannREde PetriconiRCPfeifferCVolkmerBGRadical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder without neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy: long-term results in 1100 patientsEur Urol20126151039104722381169

- ZehnderPStuderUESkinnerECSuper extended versus extended pelvic lymph node dissection in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: a comparative studyJ Urol201118641261126821849183

- MadersbacherSHochreiterWBurkhardFRadical cystectomy for bladder cancer today – a homogeneous series without neoadjuvant therapyJ Clin Oncol200321469069612586807

- SteinJPLymphadenectomy in bladder cancer: how high is “high enough”?Urol Oncol200624434935516818190

- BruinsHMHuangGJCaiJSkinnerDGSteinJPPensonDFClinical outcomes and recurrence predictors of lymph node positive urothelial cancer after cystectomyJ Urol200918252182218719758623

- HerrHWDonatSMOutcome of patients with grossly node positive bladder cancer after pelvic lymph node dissection and radical cystectomyJ Urol20011651626411125364

- DharNBKleinEAReutherAMThalmannGNMadersbacherSStuderUEOutcome after radical cystectomy with limited or extended pelvic lymph node dissectionJ Urol2008179387387818221953

- HerrHWExtent of surgery and pathology evaluation has an impact on bladder cancer outcomes after radical cystectomyUrology200361110510812559278

- LeissnerJHohenfellnerRThuroffJWWolfHKLymphadenectomy in patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder; significance for staging and prognosisBJU Int200085781782310792159

- PoulsenALHornTStevenKRadical cystectomy: extending the limits of pelvic lymph node dissection improves survival for patients with bladder cancer confined to the bladder wallJ Urol19981606 Pt 1201520199817313

- swog.org [homepage on the Internet]SWOG S1011 Bladder Cancer Trial: Patient Information Available from: http://swog.org/patients/s1011/Accessed June 28, 2013

- Association of Urogenital Oncology (AUO)Eingeschränkte vs Ausgedehnte Lymphadenektomie LEA [Limited vs Extended lymphadenectomy LEA]ClinicalTrialsgov [website on the Internet]Bethesda, MDUS National Library of Medicine2011 [updated September 7, 2011]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01215071Accessed June 28, 2013 German

- RothBWissmeyerMPZehnderPA new multimodality technique accurately maps the primary lymphatic landing sites of the bladderEur Urol200957220521119879039

- RothBZehnderPBirkhauserFDBurkhardFCThalmannGNStuderUEIs bilateral extended pelvic lymphadenectomy necessary for strictly unilateral invasive bladder cancer?J Urol201218751577158222425077

- Abol-EneinHEl-BazMAbd El-HameedMAAbdel-LatifMGhoneimMALymph node involvement in patients with bladder cancer treated with radical cystectomy: a patho-anatomical study – a single center experienceJ Urol20041725 Pt 11818182115540728

- DanglePPGongMCBahnsonRRPoharKSHow do commonly performed lymphadenectomy templates influence bladder cancer nodal stage?J Urol2010183249950320006856

- LeissnerJGhoneimMAAbol-EneinHExtended radical lymphadenectomy in patients with urothelial bladder cancer: results of a prospective multicenter studyJ Urol2004171113914414665862

- WeingärtnerKRamaswamyABittingerAGerharzEWVogeDRiedmillerHAnatomical basis for pelvic lymphadenectomy in prostate cancer: results of an autopsy study and implications for the clinicJ Urol19961566196919718911367

- DaviesJDSimonsCMRuhotinaNBarocasDAClarkPEMorganTMAnatomic basis for lymph node counts as measure of lymph node dissection extent: a cadaveric studyUrology201381235836323374802

- FleischmannAThalmannGNMarkwalderRStuderUEExtracapsular extension of pelvic lymph node metastases from urothelial carcinoma of the bladder is an independent prognostic factorJ Clin Oncol200523102358236515800327

- SeilerRvon GuntenMThalmannGNFleischmannAPelvic lymph nodes: distribution and nodal tumour burden of urothelial bladder cancerJ Clin Pathol201063650450720364028

- MitraASyanRSkinnerECMirandaGDaneshmandSFactors influencing lymph node yield during radical cystectomy with extended pelvic lymphadenectomy: single-institution experience with a standardized dissection templateJ Urol20121874771

- KonetyBRJoslynSAO’DonnellMAExtent of pelvic lymphadenectomy and its impact on outcome in patients diagnosed with bladder cancer: analysis of data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program data baseJ Urol2003169394695012576819

- HollenbeckBKYeZWongSLMontieJEBirkmeyerJDHospital lymph node counts and survival after radical cystectomyCancer2008112480681218085612

- HerrHWBochnerBHDalbagniGDonatSMReuterVEBajorinDFImpact of the number of lymph nodes retrieved on outcome in patients with muscle invasive bladder cancerJ Urol200216731295129811832716

- BrossnerCPychaATothAMianCKuberWDoes extended lymphadenectomy increase the morbidity of radical cystectomy?BJU Int2004931646614678370

- DesaiMMBergerAKBrandinaRRRobotic and laparoscopic high extended pelvic lymph node dissection during radical cystectomy: technique and outcomesEur Urol201261235035522036642

- HellenthalNJRamirezMLEvansCPDevere WhiteRWThe role of surveillance in the treatment of patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer after chemotherapyBJU Int2010105448548819849694

- MeijerRPNunninkCJWassenaarAEStandard lymph node dissection for bladder cancer: significant variability in the number of reported lymph nodesJ Urol2012187244645022177147

- BochnerBHHerrHWReuterVEImpact of separate versus en bloc pelvic lymph node dissection on the number of lymph nodes retrieved in cystectomy specimensJ Urol200116662295229611696756

- SteinJPPensonDFCaiJRadical cystectomy with extended lymphadenectomy: evaluating separate package versus en bloc submission for node positive bladder cancerJ Urol2007177387688117296365

- GordetskyJScosyrevERashidHIdentifying additional lymph nodes in radical cystectomy lymphadenectomy specimensMod Pathol201225114014421909079

- ParkashVBifulcoCFeinnRConcatoJJainDTo count and how to count, that is the question: interobserver and intraobserver variability among pathologists in lymph node countingAm J Clin Pathol20101341424920551265

- NissanAJagerDRoystacherMMultimarker RT-PCR assay for the detection of minimal residual disease in sentinel lymph nodes of breast cancer patientsBr J Cancer200694568168516495929

- WeitzJKienlePMagenerADetection of disseminated colorectal cancer cells in lymph nodes, blood and bone marrowClin Cancer Res1999571830183610430088

- GazquezCRibalMJMarin-AguileraMBiomarkers vs conventional histological analysis to detect lymph node micrometastases in bladder cancer: a real improvement?BJU Int201211091310131622416928

- KurahashiTHaraIOkaNKamidonoSEtoHMiyakeHDetection of micrometastases in pelvic lymph nodes in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for locally invasive bladder cancer by real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR for cytokeratin 19 and uroplakin IIClin Cancer Res200511103773377715897575

- SalhabMPataniNMokbelKSentinel lymph node micrometastasis in human breast cancer: an updateSurg Oncol2011204e195e20621788132

- LiedbergFManssonWLymph node metastasis in bladder cancerEur Urol2006491132116203077

- YangXJLecksellKEpsteinJICan immunohistochemistry enhance the detection of micrometastases in pelvic lymph nodes from patients with high-grade urothelial carcinoma of the bladder?Am J Clin Pathol1999112564965310549252

- Advanced Bladder Cancer Meta-analysis CollaborationNeoadjuvant chemotherapy in invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysisLancet200336193731927193412801735

- GrossmanHBNataleRBTangenCMNeoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancerN Eng J Med20033499859866

- BajorinDFHerrHWKuhn’s paradigms: are those closest to treating bladder cancer the last to appreciate the paradigm shift?J Clin Oncol201129162135213721502548

- SeilerRFleischmannAPerrenAThalmannGNNeoadjuvant chemotherapy for urothelial bladder cancer: tumor regression is an independent predictor of survivalJ Urol20121874769

- MorganMJKooreyDJPainterDHistological tumour response to pre-operative combined modality therapy in locally advanced rectal cancerColorectal Dis20024317718312780612

- VecchioFMValentiniVMinskyBDThe relationship of pathologic tumor regression grade (TRG) and outcomes after preoperative therapy in rectal cancerInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys200562375276015936556

- BeckerKLangerRReimDSignificance of histopathological tumor regression after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in gastric adenocarcinomas: a summary of 480 casesAnn Surg2011253593493921490451

- LangerROttKFeithMLordickFSiewertJRBeckerKPrognostic significance of histopathological tumor regression after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in esophageal adenocarcinomasMod Pathol200922121555156319801967

- MandardAMDalibardFMandardJCPathologic assessment of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy of esophageal carcinoma. Clinicopathologic correlationsCancer19947311268026868194005

- FangACAhmadAEWhitsonJMFerrellLDCarrollPRKonetyBREffect of a minimum lymph node policy in radical cystectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy on lymph node yields, lymph node positivity rates, lymph node density, and survivorship in patients with bladder cancerCancer201011681901190820186823

- HerrHLeeCChangSLernerSBladder Cancer Collaborative GroupStandardization of radical cystectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection for bladder cancer: a collaborative group reportJ Urol200417151823182815076285

- MayMHerrmannEBolenzCAssociation between the number of dissected lymph nodes during pelvic lymphadenectomy and cancer-specific survival in patients with lymph node-negative urothelial carcinoma of the bladder undergoing radical cystectomyAnn Surg Oncol20111872018202521246405

- WrightJLLinDWPorterMPThe association between extent of lymphadenectomy and survival among patients with lymph node metastases undergoing radical cystectomyCancer2008112112401240818383515

- DorinRPDaneshmandSEisenbergMSLymph node dissection technique is more important than lymph node count in identifying nodal metastases in radical cystectomy patients: a comparative mapping studyEur Urol201160594695221802833

- HerrHWSuperiority of ratio based lymph node staging for bladder cancerJ Urol2003169394394512576818

- MayMHerrmannEBolenzCLymph node density affects cancer-specific survival in patients with lymph node-positive urothelial bladder cancer following radical cystectomyEur Urol201159571271821296488

- LeeEKHerrHWDicksteinRJLymph node density for patient counselling about prognosis and for designing clinical trials of adjuvant therapies after radical cystectomyBJU Int201211011 Pt BE590E59522758775

- ClaytonFHopkinsCLPathologic correlates of prognosis in lymph node-positive breast carcinomasCancer1993715178017908383579

- FleischmannASchobingerSMarkwalderRPrognostic factors in lymph node metastases of prostatic cancer patients: the size of the metastases but not extranodal extension independently predicts survivalHistopathology200853446847518764879

- SugitaniIFujimotoYYamamotoNPapillary thyroid carcinoma with distant metastases: survival predictors and the importance of local controlSurgery20081431354218154931

- SobinLHWittekindCTNM Classification of Malignant Tumours7th EditionNew YorkWiley-Blackwell2009

- FrankIChevilleJCBluteMLTransitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder with regional lymph node involvement treated by cystectomy: clinicopathologic features associated with outcomeCancer200397102425243112733141

- JeongIGRoJYKimSCExtranodal extension in node-positive bladder cancer: the continuing controversyBJU Int20101081384321070576

- KassoufWLeiboviciDMunsellMFDinneyCPGrossmanHBKamatAMEvaluation of the relevance of lymph node density in a contemporary series of patients undergoing radical cystectomyJ Urol20061761535716753366

- SeilerRvon GuntenMThalmannGNFleischmannAExtracapsular extension but not the tumour burden of lymph node metastases is an independent adverse risk factor in lymph node-positive bladder cancerHistopathology201158457157821401697

- StephensonAJGongMCCampbellSCFerganyAFHanselDEAggregate lymph node metastasis diameter and survival after radical cystectomy for invasive bladder cancerUrology201075238238619819539

- FajkovicHChaEKJeldresCExtranodal extension is a powerful prognostic factor in bladder cancer patients with lymph node metastasisEur Urol EpubJuly202012

- TilkiDShariatSFLotanYLymphovascular invasion is independently associated with bladder cancer recurrence and survival in patients with final stage T1 disease and negative lymph nodes after radical cystectomyBJU Int201311181215122123181623

- XylinasERinkMRobinsonBDImpact of histological variants on oncological outcomes of patients with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder treated with radical cystectomyEur J Cancer20134981889189723466126

- FritscheHMMayMDenzingerSPrognostic value of perinodal lymphovascular invasion following radical cystectomy for lymph node-positive urothelial carcinomaEur Urol201363473974423079053