Abstract

The cannabis withdrawal syndrome (CWS) is a criterion of cannabis use disorders (CUDs) (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition) and cannabis dependence (International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-10). Several lines of evidence from animal and human studies indicate that cessation from long-term and regular cannabis use precipitates a specific withdrawal syndrome with mainly mood and behavioral symptoms of light to moderate intensity, which can usually be treated in an outpatient setting. Regular cannabis intake is related to a desensitization and downregulation of human brain cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptors. This starts to reverse within the first 2 days of abstinence and the receptors return to normal functioning within 4 weeks of abstinence, which could constitute a neurobiological time frame for the duration of CWS, not taking into account cellular and synaptic long-term neuroplasticity elicited by long-term cannabis use before cessation, for example, being possibly responsible for cannabis craving. The CWS severity is dependent on the amount of cannabis used pre-cessation, gender, and heritable and several environmental factors. Therefore, naturalistic severity of CWS highly varies. Women reported a stronger CWS than men including physical symptoms, such as nausea and stomach pain. Comorbidity with mental or somatic disorders, severe CUD, and low social functioning may require an inpatient treatment (preferably qualified detox) and post-acute rehabilitation. There are promising results with gabapentin and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol analogs in the treatment of CWS. Mirtazapine can be beneficial to treat CWS insomnia. According to small studies, venlafaxine can worsen the CWS, whereas other antidepressants, atomoxetine, lithium, buspirone, and divalproex had no relevant effect. Certainly, further research is required with respect to the impact of the CWS treatment setting on long-term CUD prognosis and with respect to psychopharmacological or behavioral approaches, such as aerobic exercise therapy or psychoeducation, in the treatment of CWS. The up-to-date ICD-11 Beta Draft is recommended to be expanded by physical CWS symptoms, the specification of CWS intensity and duration as well as gender effects.

Introduction

Cannabis is a psychotropic substance with widespread recreational use worldwide, surpassed only by nicotine and alcohol.Citation1 Its use continues to be high in West and Central Africa, Western and Central Europe, Australasia, and North America, where recently an increase in the prevalence of past year cannabis use was recorded in the USA (12.6%).Citation1 In Europe, prevalence rates of annual cannabis use rise in Nordic countries (7%–18%) and France (22%). They decline in Spain, UK, and Germany (currently 12%), and there is an increase in the number of treatment demands for cannabis-related problems across EuropeCitation2 and the USA.Citation3 Although such prevalence rates are useful to indicate consumption trends, it is doubted whether these rates are relevant to reflect a health risk. Approximately 1% of European adolescents and young adults use cannabis daily or almost daily (defined as use on ≥20 days in the last month),Citation2 a consumption pattern which is more likely to produce cannabis-related disabling disorders.Citation4,Citation5 The prevalence of cannabis dependence (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition – Text Revision [DSM-IV-TR]) is highest in Australasia (0.68%), followed by North America (0.60%), Western Europe (0.34%), Asia Central (0.28%), and southern Latin America (0.26%).Citation4 In Germany, ~0.5% of the adult population have a cannabis dependence diagnosis.Citation6 Most of the other regions of the world providing data report a prevalence of cannabis dependence of <0.2%.Citation4 There is a significant positive correlation between the region’s economic situation and the prevalence of cannabis dependence.Citation4 A hallmark of cannabis dependence (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition [DSM-IV] or International Classification of Diseases [ICD]- 10) as well as cannabis use disorder (CUD) (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition [DSM-5]) is the cannabis withdrawal syndrome (CWS) that characteristically occurs after quitting a regular cannabis use abruptly.

Although there was early evidence from animal experimentsCitation7 and despite observations in humans in every decade,Citation8,Citation9 CWS entity was doubted before the 1990s, when a new cannabis wave started to roll in worldwide, particularly in affluent regions.Citation4 This was related with a mounting number of patients seeking treatment due to various cannabis-related disorders, including cognitive deficits, psychosis, and dependence.Citation4,Citation5 Considering these populations and also nontreatment-seeking cannabis-dependent individuals, larger retrospective clinical trialsCitation10,Citation11 demonstrated that discontinuation of regular cannabis use is frequently followed by waxing and waning behavioral, mood and physical symptoms such weakness, sweating, restlessness, dysphoria, sleeping problems, anxiety, and craving, which are subsequently positively associated with relapse to cannabis use.Citation11–Citation19 However, other studies did not find this association.Citation20 CWS was further validated by epidemiological,Citation21,Citation22 retrospective,Citation11,Citation19,Citation23 and prospective outpatientCitation12,Citation13,Citation20,Citation24–Citation26 and inpatient laboratory studiesCitation27–Citation30 (). Based on this research, diagnostic criteria of CWS were newly included in DSM-5 ().Citation31 In ICD-10, CWS is still vaguely definedCitation32 and awaits due definition in ICD-11.Citation33 More recent clinical inpatient detoxification studies arranging controlled abstinence conditions confirmed the entity of CWS.Citation34–Citation36 The CWS was also verified in youths and adolescents (aged 13–19 years), who sought treatment for their disabilitating cannabis dependence.Citation18,Citation37–Citation40

Table 1 Clinical and laboratory studies on human CWS in the past 20 years

Table 2 Marijuana Withdrawal Checklist (MWC)

There is a consistent evidence that CWS occurs in ~90% of the patients being diagnosed with cannabis dependence according to ICD-10 or DSM-IVCitation12,Citation13,Citation38,Citation41,Citation42 (). Among them, most often, male adolescents and young adults demonstrated a significant loss of quality of life during their cannabis dependence as measured by disability-adjusted life years in the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study (cf and in http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0076635, accessed November 25, 2016).Citation4

Recent studies revealed that 35%–75% patients seeking outpatient cannabis detoxification developed a CWS post-cessation, which usually seemed to be mild to moderate in severity.Citation11–Citation13,Citation15,Citation16,Citation19 However, most of the cannabis dependents developed a CWS of greater severity.Citation36 Adult cannabis dependents were shown to develop a severe CWS likelier than adolescent frequent users.Citation24,Citation37 A prolonged and heavier cannabis use predicts a stronger CWS.Citation12,Citation13,Citation19 It was confirmed again more recently that the occurrence of CWS is a highly specific indicator of a cannabis dependence, particularly in adolescents and young adults.Citation42

This review intends to provide a synthesis of current evidence on the biology and clinical characteristics of the human CWS and its treatment. In addition, it includes information on the role of CWS in the course of CUDCitation31 or cannabis dependence.Citation22,Citation43

Materials and methods

This study is a review of the current literature on human CWS. The search for articles was performed on the PubMedCitation44 (Med-line) and Scopus,Citation45 using the a combination of the search terms “cannabis withdrawal,” “humans,” “epidemiology,” “disability,” “clinical studies,” “clinical trials,” “case reports,” “cannabis use disorder,” “cannabis dependence,” “treatment,” “psychotherapy,” “psychosocial,” “exercise,” “occupational therapy,” “pharmacotherapy,” and “potency”. In addition, an active search for related literature was carried out in the reference lists of the selected publications. In total, 2,440 documents were screened, and mainly those studies providing information on human CWS and those published in English or German (N=101) were considered. Articles published up to November 25, 2016, were included.

Human biological background

The cannabis plant contains >420 chemical compounds of which 61 being cannabinoids themselves being defined to bind to cannabinoid 1 and 2 (CB1, CB2) receptors.Citation46 Regular cannabis use is associated with neuroanatomic abnormalities within brain regions with a high density of CB1 receptors, particularly the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.Citation47,Citation48 It is assumed that, the main psychoactive ingredient of cannabis, the partial CB1 receptor agonist delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is involved in the etiology of this damage,Citation47 which certainly awaits further study. For instance, a contribution of receptor-independent mechanisms of cannabinoidsCitation49,Citation50 as well as distress due to psychiatric CUD or CWS cannot as yet be excluded. A crucial role of THC in the genesis of CWS in humans is demonstrated by 1) pharmacokinetic studies showing a hysteresis effect between the decrease in plasma THC and onset of CWS,Citation51,Citation52 2) an abstinence syndrome following oral THCCitation12,Citation13 and THC analogs,Citation53 3) alleviation of CWS by oral THC and THC analogs,Citation29,Citation54,Citation55 and 4) the occurrence of CWS-like symptoms after quitting recreational intake of synthetic cannabinoid (SC) receptor agonists, often being full CB1 receptor agonists, differing from THC being a partial agonist.Citation56,Citation57 The withdrawal syndrome of SCs binding closer to CB1 receptors than THC seemed to be stronger than CWS and obviously showed characteristics unknown to CWS, such as seizures.Citation58 Otherwise, single cases of patients with diagnosed epilepsy who quit regular cannabis use are reported to exacerbate,Citation59 which is attributed to an anticonvulsive effect of cannabis.Citation46 The psychoactive potency of bred cannabis products sold for recreational use has been increasing in many markets over the past decade,Citation1,Citation2 which could lead to a stronger withdrawal syndrome than usually known for cannabis. Intriguingly, there is one case report regarding improvement of CWS following the administration of cannabidiol,Citation60 another constituent of cannabis, shown to reverse some adverse effects of THC in the laboratory.Citation61 The cardiovascular functioning seemed to be scarcely altered during CWS.Citation62 Although the endocannabinoid system is involved in the regulation of most of the other peripheral organ systems, the immune system and the gut, too, we are unaware of any such study on the contribution of these organs to human CWS. Notably, applying a CB1 receptor antagonist (rimonabant) to cannabis-dependent patients substituted with THC analogs did not precipitate a relevant CWS.Citation63 This may be due to the low doses of rimonabant applied (20 and 40 mg) or the CWS-generating mechanisms that are at least partly independent upon CB1 receptors.Citation49,Citation50 Cannabis users with opioid dependence are less likely to experience CWS,Citation64 which may indicate the contribution of the endogenous opioid system. In a laboratory study, the µ-opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone was recently shown to reduce self-administration of active cannabis and its related subjective positive effects on heavy cannabis users.Citation65 The authors are unaware of any study having directly examined the effect of naltrexone on the CWS under naturalistic conditions.

Abstinence-induced craving is associated with reduced amygdala volumes in frequent adolescent cannabis users, which was also found in adult alcohol and cocaine users.Citation66 Thus, the specificity of this finding for CWS is doubted and may represent a more general precursor of substance abuse itself;Citation66 that is, early stress in life.Citation67,Citation68 With respect to the three “a”s of CWS (anger, aggression, and anxiety) (), the threat-related amygdala reactivity was shown to be inversely related to the level of cannabis use in adolescents with comorbid cannabis dependence and major depression.Citation69 This finding may reflect the neurobiological basis of these transient, mostly short-lasting CWS symptoms, thus possibly being even rebound “amygdala-related” symptoms after quitting regular cannabis use. Nevertheless, the CWS symptoms could persist even longer in genetically or epigenetically more susceptible individuals upon withdrawal.

Regular cannabis intake is related to a desensitization and downregulation of human cortical and subcortical CB1 receptors. This starts to reverse within the first 2 days of abstinence and the receptors return to normal functioning after ~4 weeks of abstinence,Citation70 which could constitute a neurobiological time frame for the duration of CWS, not taking into account cellular and synaptic long-term neuroplasticity elicited by long-term cannabis use before cessation, for example, being possibly responsible for craving. In support, cannabis dependents were recently shown to have a robust negative correlation between CB1 receptor availability in almost all brain regions and their withdrawal symptoms after 2 days of cannabis abstinence which in turn resolved in the next 28 days of abstinence.Citation71

If compared with nonusers, long-term cannabis users were demonstrated to have greater brain activity during cannabis cues relative to natural reward cues (ie, fruit itself being superior to neutral cues) in the orbitofrontal cortex, striatum, anterior cingulate gyrus, and ventral tegmental area.Citation72 The users had positive correlations between neural response to cannabis cues in the fronto-striatal-temporal regions and subjective craving, cannabis-related problems, serum levels of THC metabolites, and the intensity of CWS. All of which were not found in non-cannabis users,Citation72 suggesting a sensitization and specificity of the brain response to cannabis cues in long-term cannabis users.Citation72

In the San Francisco Family Study, some symptoms of CWS, craving and cannabis-related paranoia were found to be heritable,Citation73 which could have been confounded by the heritability of age at first-ever use, for instance. It was suggested that genetic factors determine whether an individual may try or use cannabis; however, environmental factors are more crucial in determining whether a person develops dependence or not.Citation73 Recent findings provide evidence that the use of nicotine, alcohol, or cannabis shares genetic and environmental pathways on the way to develop a substance use disorder.Citation74 Regular intake of alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, or other drugs of abuse alters the stress response sustainablyCitation75 and, thereby, may precipitate a substance use disorder.

Characteristics of CWS

Considering the cannabis research of the last 20 years,Citation12,Citation13,Citation16,Citation18–Citation20,Citation31 there was no doubt that cessation of heavy or prolonged cannabis use is most likely followed by typical symptoms, such as

irritability

nervousness/anxiety

sleep difficulty

decreased appetite or weight loss

depressed mood

one of the following physical symptoms such as abdominal pain, shakiness/tremors, sweating, fever, chills, or headache.

According to DSM-5,Citation31 CWS (292.0) is diagnosed if three or more of these symptoms (1–6) develop within ~1 week after quitting cannabis use abruptly.Citation31 Withdrawal severity and duration can vary widely between individuals and fluctuate depending on the amount of prior cannabis use, context of cessation (eg, outpatient vs inpatient, voluntary vs involuntary), personality traits, psychiatric and somatic comorbidity, current life stressors, previous experiences, expectations, support, and severity of dependence.Citation12,Citation13 Women seeking treatment for CUD were shown to generate more frequent and more severe withdrawal symptoms than men after quitting their frequent cannabis use.Citation36,Citation76,Citation77 However, older studies did not reveal this gender effect ().

Additional heavy tobacco use was reported to be associated with stronger irritability during the CWS of adolescents.Citation40 Black adolescents were shown to have lower withdrawal complaints and experience less severe depressed mood, sleep difficulty, and nervousness/anxiety than non-Black adolescents.Citation40 In youths with conduct disorder, this disorder antedated cannabis use.Citation38

Currently, psychometrically validated cannabis withdrawal scales are unavailable. Several versions to measure CWSCitation11–Citation13,Citation16,Citation18,Citation24,Citation78 were developed, some of which compared with each user by Gorelick et al.Citation19 All these versions were based on the Marijuana Withdrawal Checklist (MWC) of Budney et al.Citation24 The MWC was originally designed with 22 items that assessed mood, behavioral, and physical symptoms and was revised to a 15-item version comprising these items that had been most frequently endorsed during cannabis withdrawalCitation12,Citation13,Citation26,Citation37 (). Later, this version builds the construct of the DSM-5 definition of CWSCitation31 (), which, however, does not consider cannabis craving and nausea.Citation31

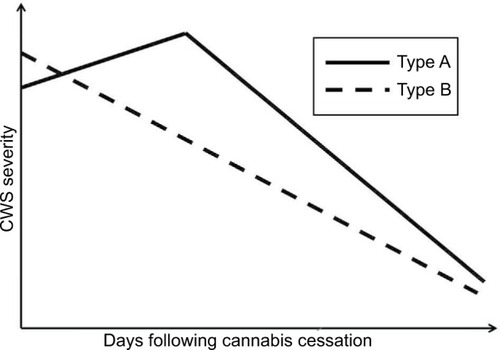

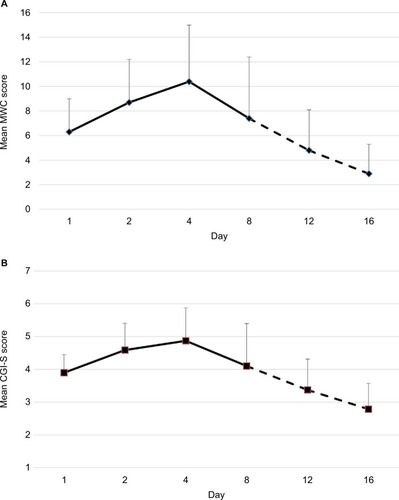

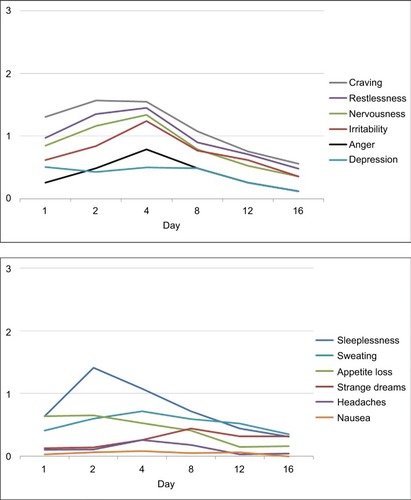

Regarding the course of the overall CWS, there were two different types described in the available literature ( and ). One peaked between the second and sixth abstinence day (type A)Citation11,Citation15,Citation16,Citation19,Citation20,Citation23,Citation26,Citation27,Citation35,Citation36,Citation56,Citation79 and the other decreased continuously following cannabis cessation (type B).Citation28,Citation34,Citation39 It is assumed that type-A CWS includes more intoxication symptoms which vanished during the first few days post-cessation, thereby unmasking the “pure” CWS.Citation36 A negative correlation with serum levels of THC at admission, which would support this assumption, was found in type A.Citation35,Citation36 Type-B CWS was not investigated to this subject. Alternative explanations are that the contribution of single items (cf and ) differed between types A and B or more patients without a measurable CWS were included in the group of patients producing a type-B course.

Figure 1 Courses of overall CWS post-cessation. The CWS usually lasts up to 3 weeks and its average peak severity (burden) is comparable to that of a moderate depression or alcohol withdrawal syndrome or in outpatient settings, similar to that of a tobacco withdrawal syndrome. Data from previous studies.Citation14,Citation36,Citation79

Figure 2 Mean and standard deviation of the (A) CWS checklist (MWC score according to previous studiesCitation24,Citation26,Citation37) and (B) the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI-S ScoreCitation80) during the course of the study. Reduced sample sizes on day 12 (n=35) and day 16 (n=28) due to regular dismissals and missed assessments are indicated by dashed lines. The effect size according to Cohen (Cohen’s d) was 1.1 for the CWS (day 1 to day 16), Cohen’s d ≥0.8 is defined to reflect a strong effect.Citation130 Vertical imaginary Y-axis: severity scores. Horizontal imaginary X-axis: time course.

Abbreviations: CWS, cannabis withdrawal syndrome; MWC, Marijuana Withdrawal Checklist.

Figure 3 Mean rating of single symptoms of the MWC (MWC score according to previous studiesCitation24,Citation26,Citation37); 4-point scale (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = heavy). Note the delayed occurrence of strange dreams.Citation25 Vertical imaginary Y-axis: severity scores. Horizontal imaginary X-axis: time course.

In the following, the course of a CWS ( and ) is presented, which was recorded during a controlled inpatient detoxification treatment of a sample consisting of long-term cannabis users (N=39, 38 Caucasians, 8 females, median age: 27 years, median daily cannabis use: 2.5 g, median duration of daily cannabis use: 36 months).Citation36 Their cannabis consumption was in the upper range if compared with other clinical studies on CWS.Citation11,Citation12,Citation16,Citation20,Citation34 All patients of this sample developed a considerable CWS.Citation36 Although this study was conducted in a large detoxification ward of a university hospital residing in a metropolitan area (Ruhr Area, Germany), it lasted 5 years (2006–2011) to find 39 appropriate patients seeking treatment due to a current sole cannabis dependence without a competing additional substance use (except for tobacco) or active comorbidity to measure a CWS as pure as possible.Citation36 This study aimed to apply both MWCCitation24 and the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI-S)Citation80 to this sample to make the severity of CWS comparable to the severity of other psychiatric disorders.Citation36 The course of the single items is shown in . Cronbach’s α coefficients were 0.67, 0.78, and 0.73 on days 4, 8, and 12, respectively.Citation36 The MWC applied to this sample achieved α coefficients comparable to that of the CWS criteria proposed for DSM-5 (0.75)Citation19 and to that of the original MWC of Budney et al (0.77).Citation12,Citation24

CWS severity in comparison with other psychiatric conditions

As outlined earlier, the severity of CWS is positively related to the cumulative amount and potency of cannabis used before cessation,Citation12,Citation13,Citation19 gender,Citation36,Citation76,Citation77 and several environmentalCitation12,Citation13,Citation73 as well as heritableCitation73 factors. Therefore, its naturalistic severity varies a lot. There are some evidences that the discomfort due to CWS is similar to that found during tobacco withdrawalCitation14,Citation79 or a moderate alcohol withdrawal syndrome.Citation36 Inpatients detoxifying from heavy cannabis use were rated to be “moderately ill” at the peak of CWS according to CGI-S.Citation36 For a first orientation, inpatients suffering from acute schizophrenic episodes and patients with acute depressive episodes in outpatient settings have been rated in the majority to be “severely ill” and “moderately ill,” respectively.Citation36 Strong CWS can mimic eating disorders associated with gastrointestinal symptoms, food avoidance, and weight loss of adolescents.Citation81

The role of nausea in CWS

There is one case report of severe nausea being associated with CWS.Citation82 In the last years, increasing cases with a cannabis-hyperemesis syndrome were noticed, which characteristically occurred in frequent and long-term cannabis users and vanished in their next 5–20 abstinent days.Citation83–Citation85 In order to differentiate this condition from CWS, we studied the course of the item “nausea” in the “cannabis burdened” sample mentioned earlier and found no correlation (r=−0.14 to 0.19) with the other items of MWC, whose internal consistency did not change, if “nausea” was excluded from the scale.Citation36 Thus, we found no evidence of nausea being a characteristic element in the orchestra of the CWS, which confirms the previous results of others.Citation11,Citation12,Citation19

Nevertheless, nausea seems to be a less common cannabis withdrawal symptom than chills, shaking, sweating, depressed mood, and stomach pain.Citation13 This is supported by the observation that nausea can occur more pronounced in the female CWS than in the male CWS.Citation76,Citation77

A retrospective chart review found preliminary evidence that “nausea and vomiting” might emerge more frequently in the withdrawal syndrome of SC agonists ()Citation56 often being full agonists at the CB1 receptor, other than the partial agonist THC.Citation57 Is this a clue that nausea breaks through when very potent agonists are removed from CB1 receptors? On the other hand, “severe nausea and vomiting” were key symptoms of the intoxication syndrome following the intravenous application of crude marijuana extractsCitation86 and are typical signs for the overdosing of smoking or swallowing cannabis preparations,Citation46,Citation86 including the first-ever intake experience. However, low to moderate amounts of cannabis preparations or THC analogs have well-known antiemetic properties.Citation46

Treatment of CWS

Cannabis detoxification treatment is usually performed in outpatient settings. However, in the case of a moderate or severe dependence syndrome, low psychosocial functioning or moderate or severe psychiatric comorbidity, an inpatient treatment is required. In Germany, inpatient cannabis detoxification is ideally performed in specialized wards following a “qualified detoxification” protocol. This includes supportive psychosocial interventions, psychoeducation, non-pharmacological symptom management, occupational and exercise therapy, professional care, as well as medical and psychiatric diagnostics and therapy of comorbid conditions. The treatment duration is related to the severity of the comorbidity or the CUD. An inpatient detoxification treatment on grounds of the diagnosis of “cannabis dependence” alone is mostly not accepted by the German health care providers, and they prima vista doubted the existence of a treatment-relevant CWS. This point of view may have a historical background, because many physicians consider cannabis to be a “soft drug,” as probably 20 years ago it contained lower THC contents.Citation87–Citation90 This view may change with a clear definition of CWS in current diagnostic classification systems, such as DSM-5.Citation31 As a rule of thumb, an “acute” inpatient detoxification treatment lasts between a few days and up to 3 weeks. In case of a too high psychiatric comorbidity and too low psychosocial functioning for an outpatient treatment, the patients could be transferred into specialized inpatient rehabilitation wards. Because this post-acute treatment approach is paid by the German Person Fund (DRV), a substantial formal request is required. The rehabilitation treatment normally lasts for several weeks and is a special feature of the German health care system. In Germany, most of the cannabis patients entering outpatient (28,000 individuals in 2014) and inpatient (3,367 individuals in 2014) rehab programs show additional problems with the co-use of alcohol (7%–14%), opioids (30%–55%), cocaine (45%–60%), stimulants (45%–70%), and pathological gambling (6%–18%).Citation91 This pattern of comorbidity is common in other high-income countries.Citation1

The effects of behavioral approaches on the mitigation of CWS were not intentionally studied, even though a beneficial action of aerobic exercise therapy can be assumed.Citation92

Currently, there are no approved medications for the treatment of CUD. Nevertheless, various pharmaceuticals have been studied in small (N<80) controlled, mostly outpatient or laboratory pilot trials: lithium, antidepressants (bupropion, nefazodone, venlafaxine, fluoxetine, escitalopram, and mirtazapine), anticonvulsants (divalproex and gabapentin), norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (atomoxetine), glutamate modulator and mucolytic agent (N-acetylcysteine), muscle relaxants (baclofen), anxiolytic (buspirone), antipsychotics (quetiapine), and CB receptor agonists (dronabinol and nabiximols).Citation55,Citation93 The antidepres sants, atomoxetine, lithium, buspirone, and divalproex had no relevant effect on the CWS or had worsened it.Citation55,Citation93 For instance, venlafaxine was shown to aggravate CWS and, thus, was accused to uphold cannabis smoking.Citation94 Quetiapine (200 mg/day) improved appetite and sleep quality during the CWS but worsened marijuana craving and drove self-administration of marijuana.Citation95 A more recent open pilot study reported a decrease of cannabis use within 8 weeks of quetiapine treatment (25–600 mg).Citation96

Putatively beneficial agents

There is evidence for an improvement of CWS with gabapentin (1200 mg/day).Citation97 The efficacy of the THC analogs dronabinol and nabiximols (plus cannabidiol) in reducing CWS is demonstrated in three small but well-controlled outpatient studies.Citation98–Citation101 An improvement of the dependence syndrome or craving was not found.Citation98–Citation101 Although innovative compounds, high costs of dronabinol or nabiximols may limit not only the use but also the abuse of these drugs. A significant effect of the THC substitution on the severity of cannabis dependence, craving, or cannabis-related problems was not found yet.Citation98–Citation101 Nabiximols is a drug containing two of the main active cannabinoids, namely, THC and cannabidiol, and has been approved in some countries for the treatment of spasticity of multiple sclerosis (MS).Citation99–Citation101 It is an oral spray formulation, and each puff of 100 µL contains 2.7 mg of THC and 2.5 mg of cannabidiol. A treatment with six puffs over the day revealed >10 times smaller blood THC concentrations than the blood concentrations known to produce psychotropic effects.Citation102 For the nabiximols regimes in the treatment of CWS, cannabis users had been instructed to take eight sprays qidCitation99,Citation100 or a maximum of four sprays every hour (up to 40 sprays/day).Citation101 Oral dronabinol had been administered in 20 mg doses three times a day.Citation98 The effectiveness of N-acetylcysteine (1200 mg/day) on CWS was not assessed directly, but this agent was shown to reduce relapse markers in the urine alongside a large (N=116) well-controlled study.Citation103 A recent laboratory study demonstrated the efficacy of the THC analog nabilon.Citation104

Because sleep difficulty is the withdrawal symptom that is assumed to be most associated with relapse to cannabis use,Citation105 a few sleeping medications were tested in the CWS treatment with first promising results for mirtazapineCitation30 and zolpidemCitation106,Citation107 during the first days of abstinence, necessarily taking care for zolpidem’s potential misuse. Nevertheless, both the drugs had no effects on CWS in general or relapse prevention.Citation30,Citation107

The withdrawal syndrome of SC receptor agonistsCitation56 awaits further characterization and may respond to benzodiazepines and quetiapine.Citation108

Impact on CUD or dependence

The CWS is part of a CUD (DSM-5)Citation31 and dependence-syndrome (ID-10, DSM-IV-R)Citation32,Citation43 being characterized by frequent, heavy, or prolonged cannabis use. The importance of the treatment of CWS on the maintenance of cannabis use or substance use trajectories over time is unclear and awaits further study. From previous literature, there is small evidence for both 1) CWS treatment initiated abstinence or dose reductionCitation12,Citation13 and 2) CWS treatment does not influence cannabis use in the following.Citation18,Citation20,Citation42,Citation109 Frequent cannabis users had reported that withdrawal symptoms negatively influence their desire and ability to quit.Citation12,Citation13,Citation18,Citation105 Two actual studies on adolescents and young adults found no association of CWS with abstinence rates being monitored up to 3 monthsCitation20 and 1 year posttreatment,Citation109 which confirmed the previous finding of Arendt et al.Citation20 Furthermore, patients with CWS relapsed sooner than those without CWS.Citation20 Patients recognizing a problem with CWS were associated with better abstinence rates than patients not recognizing a problem with CWSCitation42 pointing to a potential value of psychoeducation, an approach to be further studied in the management of CUD.

Abstaining from cannabis was reported to be followed by an increase of alcohol and tobacco use, which decreased again after continuation of cannabis use.Citation110 CWS in people with schizophrenia is associated with behavioral change, including relapse with cannabis and increased tobacco use.Citation111 “Religious support” and “prayer” were self-identified by cannabis users to be the most helpful quitting strategies and both were associated with higher 1-month and 1-year abstinence rates in these population.Citation111 Furthermore, the symptom severity of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder was positively associated with the use of cannabis (probably taken as a “self-medication”), cannabis use problems, and severity of CWS.Citation112

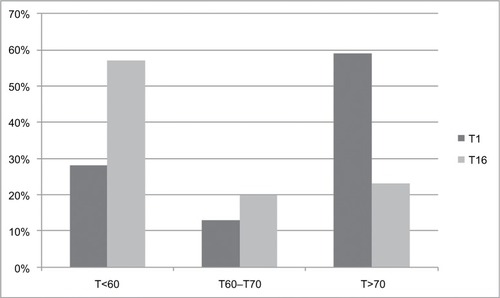

Studies that compared the effectiveness of outpatient versus inpatient treatments with respect to the severity and prognosis of CUD, especially their differential efficacy on long-term relapse prevention, dose reduction, or psychosocial functioning, are missing. At the end of a 16-day lasting inpatient detoxification treatment (qualified detox) of heavy cannabis users, the following effect sizes were found (Cohen’s d): 1.1 (CWS), 1.4 (cognition), psychiatric symptoms (0.8–0.9).Citation113 The bothersome global distress of this sample had improved significantly during the qualified detox ().

Figure 4 Significant improvement (p<0.001) of the subjective global distress of adult heavy cannabis users during inpatient qualified detoxification as measured by the Symptom Checklist 90, revised version (SCL-90-R).Citation129 Y-axis: percent of the sample (N=35); X-axis: global distress according to T-values: T<60: normal global distress; T>70: severe global distress;Citation129 T1 = admission day and T16 = last day (day 16) of the controlled inpatient qualified detoxification treatment.Citation113

At present, the effectiveness of different cannabis detoxification treatments on the course of the CUD has not been studied in depth. Outpatient treatment programs improved the psychosocial functioning and dropped the cannabis use for a while.Citation12,Citation13 Currently, only a few long-term follow-ups are available, so far showing no sustaining improvement of CUD subsequent to outpatient detoxification attempts.Citation18,Citation20,Citation42,Citation109

Discussion

With the definition of the DSM-5 criteria,Citation31 the CWS comes of age. Genetic influences on cannabis withdrawal were described to be the same as those affecting cannabis abuse and dependence.Citation114 Beyond that, the existence of the CWS has solid neurobiological underpinnings since it was found that the availability of brain CB1 receptor in cannabis dependents was inversely associated with the occurrence of CWS.Citation70,Citation71 After 4 weeks of abstinence, the anomalies of CB1 receptors binding had been normalized in cannabis dependents, thus giving a rough time frame of the duration of CWS,Citation70,Citation71 which apt to the clinical observations that have been obtained in the past 20 years (). Two different courses of CWS might result from the different contribution of cannabis residual symptoms assumed to be initially more prominent in the type A than in type B CWS.Citation36 Looking at a key symptom of cannabis use, such as “increase in appetite,”Citation5,Citation7 this was indeed reported more often in the first days of the type A CWS ().Citation19,Citation20,Citation35

Mood and behavioral symptoms, namely, insomnia, dysphoria, and anxiety, are the key symptoms of the CWS ( and ). Similar symptoms occurred in the obesity treatment with the CB-1 receptor antagonist rimonabant (also known as SR14171) and were the reason why rimonabant was withdrawn from the market in 2008.Citation115 Possibly, a “sustained CWS” had been precipitated when the effects of the physiological tone of endogenous endocannabinoids on brain and peripheral CB1 receptors were impeded by receptor antagonists, even in non-addicted but susceptible individuals. In support, the neurocircuitries involved in the regulation of stress, anxiety, and mood (such as the serotonergic, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic systems) were demonstrated to be sensitive to CB-1 receptor antagonists.Citation115

Influence of alcohol and tobacco

Regular alcohol drinking might influence the clinical expression of the CWS, and this is not through the overlapping alcohol withdrawal symptoms. Continuous exposure to ethanol, in either cell culture or rodent models, led to an increase in endocannabinoid levels that resulted in downregulation of the CB1 receptor and uncoupling of this receptor from downstream G protein signaling pathways.Citation116 A similar downregulation of CB1 receptors was found in multiple brain regions of chronic drinkers.Citation116 Alcoholic drinks were reported to be co-used by 33%–46% of regular cannabis users. The rates of co-use for cocaine, stimulants, and hallucinogens were 37%–43%, 30%–52%, and 36%–42%, respectivelyCitation1,Citation2,Citation116 – all putatively being able to influence the course and intensity of the CWS. Approximately 90% of cannabis users are also tobacco smokers, possibly reflecting the common route of administration, and even synergistic and compensatory actions of cannabis and tobacco as well as genetic and epigenetic factors assumed to mediate addiction vulnerability.Citation117,Citation118 More specifically, smoking tobacco use was shown to increase the number of cannabis dependence symptomsCitation119 and precipitated cannabis relapse.Citation120 Vice versa, cannabis use decreased the likelihood of abstaining from tobacco.Citation117,Citation118 There is a preliminary evidence that simultaneous tobacco and cannabis abstinence predicts better psychosocial treatment outcomes.Citation117,Citation118 There is still a paucity of clinical studies on this important subject, although alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis were consistently identified to be the substances with earliest onset of use, the highest prevalence of lifetime use, and the highest prevalence of lifetime disorder.Citation1–Citation6,Citation74

Choice of treatment setting

In comparison with outpatient programs, inpatient detoxifications can provide strict abstinence conditions and, thus, can be used to better differentiate CWS from comorbidity, but are much more expensive and usually not the first choice of patients seeking treatment due to CUD. However, 1) the inability to initiate cannabis abstinence due to bothersome CWS, 2) the continuous co-use of other harmful drugs of dependence, or 3) the coexistence of other disabling psychiatric or somatic complaints give reasons for the medical necessity of an inpatient detoxification program, the duration of which depends on the intensity of the withdrawal symptoms and concomitant complaints.Citation5,Citation113 At this juncture, the duration of an inpatient detoxification program of heavy cannabis users is recommended to be not less than 14 days, ideally 21 days, taken into account that their pure CWS itself usually lasted up to 14–21 days (),Citation12,Citation13,Citation36,Citation113 and the diagnosing of potentially underlying comorbidity is more sensitive from then on. It remains a challenge of future in-depth studies to compare the impact of outpatient and inpatient treatment programs on the long-term course and disability of substance use disorders, which applies to CUD, too.

Influence of high potency cannabis preparations, gender, and so on

Similar to the cannabis addiction syndrome itself,Citation121 one of its hallmark, the CWS, is based upon complex interactions between drug-induced neurobiological changes, environmental factors, genetic and epigenetic factors, comorbidity, personality traits, gender influences, and stress responsivity, all of which contributing to the high inter- and intrapersonal variations in the composition, annoyance, and duration of the CWS ().Citation12,Citation13,Citation114,Citation121

In addition to an increasing awareness of the existence of the CWS, its increasing emergence in the last 20 years might result from the increasing psychotropic potency of the used marijuana originating from the breeding of strains with high THC (10%–18.5%) and low cannabidiol concentrations (<0.15%) being found especially in high-income countries.Citation1,Citation88–Citation90,Citation122 In the Netherlands, the recent cannabidiol content of imported resin was ~7%.Citation90 According to animal experiments, cannabidiol can counterbalance some adverse effects of cannabis,Citation61 and in patient populations, there is mounting evidence of anticonvulsive and antipsychotic properties of cannabidiol.Citation123 Since the early 1950s, it is known that the chemical composition of the resin itself varies with cannabidiol activities between 0% and 50% depending on the provenance of the drug.Citation87 Whether the users of more potent cannabis strains adjust their intake according to the potency is still unclear.Citation88 However, there is first evidence that the occurrence of first-episode psychosis as well as the intensity of the CUD increased alongside the use of high potency cannabis preparations.Citation124,Citation125 This throws an extremely critical light on emerging modern cannabis ingestion methods (“dabbing” or “cannavaping” of cannabis concentrates with 20%–80% THC) used by individuals seeking a more rapid and even bigger than being possible with smoking flowers that THC contents are usually in the range of 2% and 6%.Citation126,Citation127 Marijuana users who had turned to “dabbing” reported higher tolerance and withdrawal experiences.Citation126

The CWS could have an measurement bias regarding a recent finding that it was endorsed more likely by the US than by Dutch cannabis users, which applies to other CUD criteria, such as tolerance, and gender effects on CWS, too.Citation77 In this context, recent studies revealed a consistent gender impact on CWS, because women experienced a stronger CWS ()Citation36,Citation76 and were shown to have a greater susceptibility to developing CUD than men.Citation121,Citation128 Women were also found to be more sensitive to the cannabis than men.Citation121,Citation128 Remarkably, women reported physical CWS complaints more likely, such as nausea and stomach pain ().Citation19,Citation76

CWS in the ICD-11 Beta Draft

In 2018, the 11th revision of the ICD-11 is planned to be published. The so-called Beta-Draft of the chapter about “Mental and Behavioral Disorders” is already available online at http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd11/browse/f/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f637576511 (accessed November 25, 2016).Citation33 The current version of this ICD-11 Beta DraftCitation33 lists the usual mood and behavioral CWS symptoms according to DSM-5Citation31 but does not consider physical CWS symptoms.Citation33 We recommend to include at least “nausea” and “stomach pain” into the final version because these symptoms were recently found to be more prominent in the female CWS,Citation76,Citation77,Citation121,Citation128 and yet, it seems likely that the increasing use of high potency cannabis preparations are associated with more physical CWS symptoms. It is also recommended to include a note on the high intra- and interpersonal variability of the CWS intensity and the observation that – if a CWS occurs – it is extra distressing between the first and the third week after quitting a frequent, heavy, or prolonged cannabis use ().Citation12,Citation13,Citation36 Heavy users were shown to experience a CWS whose average severity is comparable to the burden of a moderate depression or moderate alcohol withdrawal syndrome.Citation36 In outpatient settings, the average discomfort of CWS was similar to that of tobacco withdrawal.Citation14,Citation79

Certainly, it awaits future study whether the inhalation of very potent cannabis concentratesCitation126,Citation127 is indeed associated with a further decrease of psychosocial functioning, higher comorbidity, and a stronger CUD and CWS – eventually with more physical features (eg, hyperalgesia, nausea, sweating, tremor, flu-like symptoms)Citation31 than occurring after the cessation of a heavy or prolonged use of traditional non-concentrated cannabis preparations.

Conclusion

The CWS is a criterion of CUDs (DSM-5) and cannabis dependence (DSM-IV-R, ICD-10). Several lines of evidence from human studies indicate that cessation from long-term and regular cannabis use precipitates a specific withdrawal syndrome with mainly mood and behavioral symptoms of light to moderate intensity, which can usually be treated in an outpatient setting. However, comorbidity with mental or somatic disorders, severe CUD, and low social functioning may require an inpatient treatment (preferably a qualified detox) and post-acute rehabilitation or long-term outpatient care. There are promising results with gabapentin and THC analogs in the treatment of CWS. Mirtazapine could improve insomnia, and venlafaxine was found to worsen the CWS. Certainly, further research is required with respect to the impact of the CWS treatment setting on long-term CUD prognosis and with respect to psychopharmacological or behavioral approaches, such as aerobic exercise therapy or psychoeducation, in the CWS treatment. The preliminary up-to-date content for the ICD-11Citation33 (intended to be finally published in 2018) is recommended to be expanded by physical CWS-symptoms, the specification of CWS severity and duration as well as gender effects.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- UNDOC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime)World Drug Report 2015United Nations publication, Sales No. E.15.XI.6 Available from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr2015/World_Drug_Report_2015.pdfAccessed September 28, 2016

- EMCDDA (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction)European Drug Report 2015. Trends and Developments. Lux-embourg Publication Office of the European Union 2015 Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_239505_EN_TDAT15001ENN.pdfAccessed September 28, 2016

- HasinDSSahaTDKerridgeBTPrevalence of Marijuana Use Disorders in the United States Between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. Prevalence of Marijuana Use Disorders in the United States Between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013JAMA Psychiatry201572121235124226502112

- DegenhardtLFerrariAJCalabriaBThe global epidemiology and contribution of cannabis use and dependence to the global burden of disease: results from the GBD 2010 studyPLoS One2013810e7663524204649

- HochEBonnetUThomasiusRGanzerFHavemann-ReineckeUPreussUWRisks associated with the non-medicinal use of cannabisDtsch Arztebl Int20151121627127825939318

- PabstAKrausLGomes de MatosEPiontekDSubstanzkonsum und substanzbezogene Störungen in Deutschland im Jahr 2012Sucht201359321331

- PatonWDCannabis and its problemsProc R Soc Med19736677187214582312

- FraserJDWithdrawal symptoms in cannabis-indica addictsLancet19492658274715390694

- BensuanADMarihuana withdrawal symptomsBr Med J197135766112

- WiesbeckGASchuckitMAKalmijnJATippJEBucholzKKSmithTLAn evaluation of the history of a marijuana withdrawal syndrome in a large populationAddiction19969110146914788917915

- LevinKHCopersinoMLHeishmanSJCannabis withdrawal symptoms in non-treatment-seeking adult cannabis smokersDrug Alcohol Depend201011112012720510550

- BudneyAJHughesJRMooreBAVandreyRReview of the validity and significance of cannabis withdrawal syndromeAm J Psychiatry20041611967197715514394

- BudneyAJHughesJRThe cannabis withdrawal syndromeCurr Opin Psychiatry200619323323816612207

- BudneyAJVandreyRGHughesJRThostensonJDBursacZComparison of cannabis and tobacco withdrawal: severity and contribution to relapseJ Subst Abuse Treat200835436236818342479

- AllsopDJNorbergMMCopelandJFuSBudneyAJThe cannabis withdrawal scale development: patterns and predictors of cannabis withdrawal and distressDrug Alcohol Depend201111912312921724338

- AllsopDJCopelandJNorbergMMQuantifying the clinical significance of cannabis withdrawalPLoS One201279e4486423049760

- CorneliusJRChungTMartinCWoodDSClarkDBCannabis withdrawal is common among treatment-seeking adolescents with cannabis dependence and major depression, and is associated with rapid relapse to dependenceAddict Behav200833111500150518313860

- ChungTMartinCSCorneliusJRClarkDBCannabis withdrawal predicts severity of cannabis involvement at 1-year follow-up among treated adolescentsAddiction2008103578779918412757

- GorelickDALevinKHCopersinoMLDiagnostic criteria for cannabis withdrawal syndromeDrug Alcohol Depend201212314114722153944

- ArendtMRosenbergRFoldagerLSherLMunk-JørgensenPWithdrawal symptoms do not predict relapse among subjects treated for cannabis dependenceAm J Addict20071646146718058411

- AgrawalAPergadiaMLLynskeyMTIs there evidence for symptoms of cannabis withdrawal in the national epidemiologic survey of alcohol and related conditions?Am J Addict20081719920818463997

- HasinDSKeyesKMAldersonDWangSAharonovichEGrantBFCannabis withdrawal in the United States: results from NESARCJ Clin Psychiatry2008691354136319012815

- CopersinoMLBoydSJTashkinDPCannabis withdrawal among non-treatment-seeking adult cannabis usersAm J Addict200615181416449088

- BudneyAJNovyPLHughesJRMarijuana withdrawal among adults seeking treatment for marijuana dependenceAddiction19999491311132210615717

- BudneyAJHughesJRMooreBANovyPLMarijuana abstinence effects in marijuana smokers maintained in their home environmentArch Gen Psychiatry2001581091792411576029

- BudneyAJMooreBAVandreyRGHughesJRThe time course and significance of cannabis withdrawalJ Abnorm Psychol2003112339340212943018

- KouriEMPopeHGJrAbstinence symptoms during withdrawal from chronic marijuana useExp Clin Psychopharmacol20008448349211127420

- HaneyMWardASComerSDFoltinRWFischmanMWAbstinence symptoms following smoked marijuana in humansPsychopharmacology (Berl)1999141439540410090647

- HaneyMHartCLVosburgSKComerSDReedSCFoltinRWEffects of THC and lofexidine in a human laboratory model of marijuana withdrawal and relapsePsychopharmacology (Berlin)200819715716818161012

- HaneyMHartCLVosburgSKEffects of baclofen and mirtazapine on a laboratory model of marijuana withdrawal and relapsePsychopharmacology (Berlin)2010211223324420521030

- APA (American Psychiatric Association)Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth ed. (DSM-5TM)Washington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2013

- DillingHMombourWSchmidtMHInternationale Klassifikation psychischer Störungen. ICD-10 Kapitel V (F). Diagnostische Kriterien für Forschung und PraxisBern, SwitzerlandHuber2004

- ICD-11 Beta Draft (Foundation)Cannabis withdrawal Available from: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd11/browse/f/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f637576511Accessed November 25, 2016

- PreussUWWatzkeABZimmermannJWongJWSchmidtCOCannabis withdrawal severity and short-term course among cannabis-dependent adolescent and young adult inpatientsDrug Alcohol Depend201010613313419783382

- LeeDSchroederJRKarschnerELCannabis withdrawal in chronic, frequent smokers during sustained abstinence within a closed residential environmentAm J Addict20142323424224724880

- BonnetUSpeckaMStratmannUOchwadtRScherbaumNAbstinence phenomena of chronic cannabis-addicts prospectively monitored during controlled inpatient detoxification: cannabis withdrawal syndrome and its correlation with delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and -metabolites in serumDrug Alcohol Depend201414318919725127704

- VandreyRBudneyAJKamonJLStangerCCannabis withdrawal in adolescent treatment seekersDrug Alcohol Depend200578220521015845324

- CrowleyTJMacdonaldMJWhitmoreEAMikulichSKCannabis dependence, withdrawal, and reinforcing effects among adolescents with conduct symptoms and substance use disordersDrug Alcohol Depend199850127379589270

- MilinRManionIDareGWalkerSProspective assessment of cannabis withdrawal in adolescents with cannabis dependence: a pilot studyJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200847217417818176332

- SoenksenSSteinLABrownJDStengelJRRossiJSLebeauRCannabis withdrawal among detained adolescents: exploring the impact of nicotine and raceJ Child Adolesc Subst Abuse201524211912425705103

- SwiftWHallWTeessonMCharacteristics of DSM-IV and ICD-10 cannabis dependence among Australian adults: results from the National Survey of Mental Health and WellbeingDrug Alcohol Depend200163214715311376919

- GreeneMCKellyJFThe prevalence of cannabis withdrawal and its influence on adolescents’ treatment response and outcomes: a 12-month prospective investigationJ Addict Med20148535936725100311

- APA (American Psychiatric Association)Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association1994

- PubMedUS National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health Search database Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedAccessed November 25, 2016

- ScopusDocument searchElsevier Available from: https://www.scopus.com/home.uriAccessed November 25, 2016

- LigrestiADe PetrocellisLDi MarzoVFrom phytocannabinoids to cannabinoid receptors and endocannabinoids: pleiotropic physiological and pathological roles through complex pharmacologyPhysiol Rev20169641593165927630175

- BhattacharyyaSAtakanZMartin-SantosRCrippaJAMcGuirePKNeural mechanisms for the cannabinoid modulation of cognition and affect in man: a critical review of neuroimaging studiesCurr Pharmaceut Des20121850455054

- LorenzettiVSolowijNYücelMThe role of cannabinoids in neuroanatomic alterations in cannabis usersBiol Psychiatry2016797e17e3126858212

- OzMReceptor-independent actions of cannabinoids on cell membranes: focus on endocannabinoidsPharmacol Ther2006111111414416584786

- Manjarrez-MarmolejoJFranco-PérezJGap junction blockers: an overview of their effects on induced seizures in animal modelsCurr Neuropharmacol201614775977127262601

- ConeEJHuestisMARelating blood concentrations of terahydrocan-nabinoland metabolites to pharmacologic effects and time of marijuana usageTher Drug Monit1993155275328122288

- LaprevoteVGambierNCridligJEarly withdrawal effects in a heavy cannabis smoker during hemodialysisBiol Psychiatry2015775e25e2625444165

- MuramatsuRSSilvaNAhmedISuspected dronabinol withdrawal in an elderly cannabis-naïve medically ill patientAm J Psychiatry2013170780423820836

- HaneyMCooperZDBediGVosburgSKComerSDFoltinRWNabilone decreases marijuana withdrawal and a laboratory measure of marijuana relapseNeuropsychopharmacology201540112489249825881117

- BalterRECooperZDHaneyMNovel pharmacologic approaches to treating cannabis use disorderCurr Addict Rep20141213714324955304

- MacfarlaneVChristieGSynthetic cannabinoid withdrawal: a new demand on detoxification servicesDrug Alcohol Rev201534214715325588420

- WileyJLMarusichJAHuffmanJWMoving around the molecule: relationship between chemical structure and in vivo activity of synthetic cannabinoidsLife Sci2014971556324071522

- SampsonCSBedySMCarlisleTWithdrawal seizures seen in the setting of synthetic cannabinoid abuseAm J Emerg Med201533111712.e3

- HegdeMSantos-SanchezCHessCPKabirAAGarciaPASeizure exacerbation in two patients with focal epilepsy following marijuana cessationEpilepsy Behav201225456356623159379

- CrippaJAHallakJEMachado-de-SousaJPCannabidiol for the treatment of cannabis withdrawal syndrome: a case reportJ Clin Pharm Ther201338216216423095052

- NiesinkRJvan LaarMWDoes cannabidiol protect against adverse psychological effects of THC?Front Psychiatry2013413024137134

- BonnetUAbrupt quitting of long-term heavy recreational cannabis use is not followed by significant changes in blood pressure and heart ratePharmacopsychiatry2016491232526761126

- GorelickDAGoodwinRSSchwilkeEAntagonist-elicited cannabis withdrawal in humansClin Psychopharmacol2011315603612

- ChauchardEGoncharovOKrupitskyEGorelickDACannabis withdrawal in patients with and without opioid dependenceSubst Abuse2014353230234

- HaneyMRameshDGlassAPavlicovaMBediGCooperZDNaltrexone maintenance decreases cannabis self-administration and subjective effects in daily cannabis smokersNeuropsychopharmacology201540112489249825881117

- PadulaCBMcQueenyTLisdahlKMPriceJSTapertSFCraving is associated with amygdala volumes in adolescent marijuana users during abstinenceAm J Drug Alcohol Abuse201541212713225668330

- McEwenBSPhysiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brainPhysiol Rev200787387390417615391

- AleksićDAksićMRadonjićNVLong-term effects of maternal deprivation on the volume, number and size of neurons in the amygdala and nucleus accumbens of ratsPsychiatr Danub201628321121927658829

- CorneliusJRAizensteinHJHaririARAmygdala reactivity is inversely related to level of cannabis use in individuals with comorbid cannabis dependence and major depressionAddict Behav201035664464620189314

- HirvonenJGoodwinRSLiC-TReversible and regionally selective downregulation of brain cannabinoid CB1-receptors in chronic daily cannabis smokersMol Psychiatry20121764264921747398

- D’SouzaDCCortes-BrionesJARanganathanMRapid changes in CB1 receptor availability in cannabis dependent males after abstinence from cannabisBiol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging201611606726858993

- FilbeyFMDunlopJKetchersideAfMRI study of neural sensitization to hedonic stimuli in long-term, daily cannabis usersHum Brain Mapp201637103431344327168331

- EhlersCLGizerIRVietenCCannabis dependence in the San Francisco Family Study: age of onset of use, DSM-IV symptoms, withdrawal, and heritabilityAddict Behav201035210211019818563

- Richmond-RakerdLSSlutskeWSLynskeyMTAge at first use and later substance use disorder: shared genetic and environmental pathways for nicotine, alcohol, and cannabisJ Abnorm Psychol2016125794695927537477

- FosnochtAQBriandLASubstance use modulates stress reactivity: behavioral and physiological outcomesPhysiol Behav2016166324226907955

- HerrmannESWeertsEMVandreyRSex differences in cannabis withdrawal symptoms among treatment-seeking cannabis usersExp Clin Psychopharmacol201523641542126461168

- DelforterieMCreemersHAgrawalAFunctioning of cannabis abuse and dependence criteria across two different countries: the United States and the NetherlandsSubst Use Misuse201550224225025363693

- BrownSAMyersMGLippkeLTapertSFStewartDGVikPWPsychometric evaluation of the Customary Drinking and Drug Use Record (CDDR): a measure of adolescent alcohol and drug involvementJ Stud Alcohol19985944274389647425

- VandreyRGBudneyAJHughesJRLiguoriAA within-subject comparison of withdrawal symptoms during abstinence from cannabis, tobacco, and both substancesDrug Alcohol Depend2008921–3485417643868

- BusnerJTargumSDThe clinical global impression scale: applying a research tool in clinical practicePsychiatry (Edgemont)200742837

- ChesneyTMatsosLCouturierJJohnsonNCannabis withdrawal syndrome: an important diagnostic consideration in adolescents presenting with disordered eatingInt J Eat Disord201447221922324281745

- LamPWFrostDWNabilone therapy for cannabis withdrawal presenting as protracted nausea and vomitingBMJ Case Rep20142014

- AllenJHde MooreGMHeddleRTwartzJCCannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuseGut200453111566157015479672

- BonnetUChangDIScherbaumNCannabis-Hyperemesis-Syndrom [Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome]Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr201280298101 German21692016

- HeiseLCannabinoid hyperemesis syndromeAdv Emerg Nurs J20153729510125929220

- VaziriNDThomasRSterlingMToxicity with intravenous injection of crude marijuana extractClin Toxicol1981183533667237964

- GrlicLA comparative study on some chemical and biological characteristics of various samples of cannabis resinUNDOC1962 Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/bulletin/bulletin_1962-01-01_3_page005.htmlAccessed November 25, 2016

- CresseyDThe cannabis experimentNature2015524756528028326295084

- SwiftWWongALiKMArnoldJCMcGregorISAnalysis of cannabis seizures in NSW, Australia: cannabis potency and cannabinoid profilePLoS One201387e7005223894589

- NiesinkRJRigterSKoeterMWBruntTMPotency trends of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and cannabinol in cannabis in the Netherlands: 2005–15Addiction2015110121941195026234170

- BraunBKünzelJBrandHKapitel 31: Jahresstatistik 2014 der professionellen SuchtkrankenhilfeDeutsche Hauptstellen für Suchtfragen eV, editor Jahrbuch Sucht 2016Lengerich, GermanyPabst Verlag2016173199

- BuchowskiMSMeadeNNCharboneauEParkSDietrichMSCowanRLMartinPRAerobic exercise training reduces cannabis craving and use in non-treatment seeking cannabis-dependent adultsPLoS One201163e1746521408154

- CopelandJPokorskiIProgress toward pharmacotherapies for cannabis-use disorder: an evidence-based reviewSubst Abuse Rehab201674153

- KellyMAPavlicovaMGlassADo withdrawal-like symptoms mediate increased marijuana smoking in individuals treated with venlafaxine-XR?Drug Alcohol Depend2014144424625283697

- CooperZDFoltinRWHartCLVosburgSKComerSDHaneyMA human laboratory study investigating the effects of quetiapine on marijuana withdrawal and relapse in daily marijuana smokersAddict Biol2013186993100222741619

- MarianiJJPavlicovaMMamczurAKBisagaANunesEVLevinFROpen-label pilot study of quetiapine treatment for cannabis dependenceAm J Drug Alcohol Abuse201440428028424963729

- MasonBJCreanRGoodellVA proof-of-concept randomized controlled study of gabapentin: effects on cannabis use, withdrawal and executive function deficits in cannabis-dependent adultsNeuropsychopharmacology20123771689169822373942

- LevinFRMarianiJJBrooksDJPavlicovaMChengWNunesEVDronabinol for the treatment of cannabis dependence: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialDrug Alcohol Depend20111161–314215021310551

- AllsopDJCopelandJLintzerisNNabiximols as an agonist replacement therapy during cannabis withdrawal: a randomized clinical trialJAMA Psychiatry201471328129124430917

- AllsopDJLintzerisNCopelandJDunlopAMcGregorISCannabinoid replacement therapy (CRT): nabiximols (Sativex) as a novel treatment for cannabis withdrawalClin Pharmacol Ther201597657157425777582

- TrigoJMLagzdinsDRehmJEffects of fixed or self-titrated dosages of Sativex on cannabis withdrawal and cravingsDrug Alcohol Depend201616129830626925704

- IndoratoFLibertoALeddaCRomanoGBarberaNThe therapeutic use of cannabinoids: forensic aspectsForensic Sci Int201626520020327038587

- GrayKMCarpenterMJBakerNLA double-blind randomized controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine in cannabis-dependent adolescentsAm J Psychiatry2012169880581222706327

- HaneyMCooperZDBediGVosburgSKComerSDFoltinRWNabilone decreases marijuana withdrawal and a laboratory measure of marijuana relapseNeuropsychopharmacology201540112489249825881117

- BudneyAJVandreyRGStangerCPharmacological and psychosocial interventions for cannabis use disordersRev Bras Psiquiatr201032Suppl 1S46S5520512270

- VandreyRSmithMTMcCannUDBudneyAJCurranEMSleep disturbance and the effects of extended-release zolpidem during cannabis withdrawalDrug Alcohol Depend20111171384421296508

- HerrmannESCooperZDBediGEffects of zolpidem alone and in combination with nabilone on cannabis withdrawal and a laboratory model of relapse in cannabis usersPsychopharmacology (Berl)2016233132469247827085870

- CooperZDAdverse effects of synthetic cannabinoids: management of acute toxicity and withdrawalCurr Psychiatry Rep20161855227074934

- DavisJPSmithDCMorphewJWLeiXZhangSCannabis withdrawal, posttreatment abstinence, and days to first cannabis use among emerging adults in substance use treatment: a prospective studyJ Drug Issues2016461648326877548

- AllsopDJDunlopAJSaddlerCRivasGRMcGregorISCopelandJChanges in cigarette and alcohol use during cannabis abstinenceDrug Alcohol Depend2014138546024613633

- KoolaMMBoggsDLKellyDLRelief of cannabis withdrawal symptoms and cannabis quitting strategies in people with schizophreniaPsychiatry Res2013209327327823969281

- BodenMTBabsonKAVujanovicAAShortNABonn-MillerMOPosttraumatic stress disorder and cannabis use characteristics among military veterans with cannabis dependenceAm J Addict201322327728423617872

- BonnetUSpeckaMScherbaumNHäufiger Konsum von nicht-medizinischem Cannabis [Frequent non-medical cannabis use: health sequelae and effectiveness of detoxification treatment]Dtsch Med Wochenschr20161412126131 German26800074

- VerweijKJAgrawalANatNOA genetic perspective on the proposed inclusion of cannabis withdrawal in DSM-5Psychol Med20134381713172223194657

- GamaleddinIHTrigoJMGueyeABRole of the endogenous cannabinoid system in nicotine addiction: novel insightsFront Psychiatry201564125859226

- Henderson-RedmondANGuindonJMorganDJRoles for the endocannabinoid system in ethanol-motivated behaviorProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry20166533033926123153

- AgrawalABudneyAJLynskeyMTThe co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: a reviewAddiction201210771221123322300456

- RabinRAGeorgeTPA review of co-morbid tobacco and cannabis use disorders: possible mechanisms to explain high rates of co-useAm J Addict201524210511625662704

- ReamGLBenoitEJohnsonBDSmoking tobacco along with marijuana increases symptoms of cannabis dependenceDrug Alcohol Depend20089519920818339491

- HaneyMBediGCooperZDPredictors of marijuana relapse in the human laboratory: robust impact of tobacco cigarette smoking statusBiol Psychiatry20137324224822939992

- FattoreLConsidering gender in cannabinoid research: a step towards personalized treatment of marijuana addictsDrug Test Anal201351576122887940

- BonnetURauschzustände: Risiken und Nebenwirkungen. Im Focus: nicht-medizinisches Cannabis und synthetische Cannabinoide [States of intoxication: risks and adverse effects: focus on non-medical cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids]Suchttherapie20161726170 German

- LewekeFMMuellerJKLangeBRohlederCTherapeutic potential of cannabinoids in psychosisBiol Psychiatry201679760461226852073

- Di FortiMMarconiACarraEProportion of patients in South London with first-episode psychosis attributable to use of high potency cannabis: a case-control studyLancet Psychiatry20152323323826359901

- FreemanTPWinstockARExamining the profile of high-potency cannabis and its association with severity of cannabis dependencePsychol Med2015453181318926213314

- LoflinMEarleywineMA new method of cannabis ingestion: the dangers of dabs?Addict Behav201439101430143324930049

- VarletVConcha-LozanoNBerthetADrug vaping applied to cannabis: is “cannavaping” a therapeutic alternative to marijuana?Sci Rep201662559927228348

- CooperZDHaneyMInvestigation of sex-dependent effects of cannabis in daily cannabis smokersDrug Alcohol Depend2014136859124440051

- FrankeGSCL-90-R. Die Symptomcheckliste von Derogatis – Deutsche Version – Manual (2.Auflage)Göttingen, GermanyHogrefe2002

- CohenJStatistical Power for the Behavioral SciencesNew YorkAcademic Press1988