Abstract

Background

Individuals with substance-use disorder (SUD) often have co-occurring mental health disorders and decreased executive function, both of which are barriers to sustained rehabilitation. Clients with severe SUD can be institutionalized in The Swedish National Board of Institutional Care but are difficult to engage and dropout rates remain high. Recent studies suggest that acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is an effective treatment for mental health and SUD.

Objectives

The overall aims of the present pilot study were to explore a manual-based ACT intervention for clients institutionalized for severe SUD and to describe the effects on mental health, psychological flexibility, and executive function. This pilot study is the first to use a manual-based ACT intervention within an inpatient context.

Methods

Eighteen participants received a seven-session ACT intervention tailored for SUD. Statistical analyses were performed for the complete data (n=18) and on an individual level of follow-up data for each participant. In order to follow and describe changes, the strategy was to assess the change in 13 clinical scales from pre-intervention to post-intervention.

Results

Results suggested that there was no change in mental health and a trend implying positive changes for psychological flexibility and for 9 of 10 executive functions (e.g., inhibitory control, task monitoring, and emotional control).

Conclusion

The pilot study suggests clinical gains in psychological flexibility and executive functions both at the Institution regulated by the Care of Alcoholics and Drugabuser Act (also known as LVM home) and at the individual level. Since the sample size does not provide adequate statistical power to generalize and to draw firm conclusions concerning intervention effects, findings are descriptive and preliminary in nature. Further development and implementation of ACT on a larger scale study, including the maintenance phase and a follow-up, is needed.

Introduction

Substance-use disorder (SUD) is a major health problem and is often associated with substantial social and personal costs.Citation1,Citation2 According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),Citation3 a diagnosis of SUD (mild, moderate, or severe alcohol or drug use) is based on the evidence of impaired control, social impairment, risky use, and pharmacological criteria. Treatments are available, but individuals are difficult to reach and dropout rates remain high. To address issues related to the mismatching of treatment to client needs, there is a need for new therapies that are well tailored, effective, and evidence based.

Every year, thousands of adults diagnosed with SUD are institutionalized by The Swedish National Board of Institutional Care (SiS), a government agency that provides individualized compulsory care. Clients forced by law into these institutions – Institutions regulated by the Care of Alcoholics and Drugabuser Act (LVM homes) – are diagnosed with SUD, and many also suffer from other mental health disorders,Citation4 such as sleeping disorders,Citation5 depression,Citation1 anxiety,Citation6 and stress,Citation5 all of which need to be managed properly since they often trigger relapse.Citation7,Citation8 Clients at LVM homes constitute an especially high-risk group since they not only suffer from mental health disorders but often also from brain trauma and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).Citation9 These conditions can negatively impact the prefrontal cortex and thus increase the risk for executive dysfunction, such as decreased inhibition,Citation10 which in turn increases the risk of relapse in SUD.Citation11 Hence, in addition to behavior challenges relating to rehabilitation, practitioners must take the emotional and cognitive functioning of individuals with SUD into consideration.

Several randomized controlled studies have shown that relatively short acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) interventions have positive effects on mental health disordersCitation12,Citation13 and on SUD.Citation7,Citation14–Citation19

The general objective in ACT is to instill psychological flexibility “allowing individuals to contact, take in, and evaluate their current circumstance, so as to act in line with one’s values without giving in to impulses”.Citation13,Citation20 Emphasizing acceptance of inner discomfort by shaping a new, open, aware and flexible way of relating to internal experiencesCitation21–Citation23 involves a set of interrelated mental functions named executive functions.Citation24,Citation25 Executive functions can be divided into behavior regulation (inhibiting, shifting of attention, emotional control, and self-monitoring) and metacognition (initiating, working memory, planning/organizing, task monitoring, and organizing of materials),Citation10 critical for individuals with SUD to follow through with treatment plans.Citation26–Citation29 Recent studies show that executive functions can be trained.Citation30,Citation31

Aim of the pilot study

The aims of the present pilot study were to explore and describe the effects of a 3-week, tailor-made, client-centered ACT intervention on mental health, psychological flexibility, and executive function of participants institutionalized for severe SUD.

Methods

ACT intervention

The present ACT manual used in this study was developed by the first author in 2015 and was based on the six key processes in ACT (present moment, defusion, acceptance, self as context, values, and committed action).Citation32,Citation33 The manual included seven × 90-minute sessions spread out evenly during a 3-week period and was focused on training in how to use the ACT principles. The intervention included daily mindfulness practices, 10 minutes each, using audio-guided instructions. Self-practice included evidence-based mindfulness practices developed by Schenstrom (further researched in Sundquist et al).Citation34

ACT instructors and coaches

Psychologists and social counselors, two from each of three different LVM homes, participated in a 4-day ACT program presented by a senior psychologist Livheim, trained in ACT, spread out evenly over an 8-week period to become ACT instructors. In parallel with the ACT program, they trained the rest of the personnel at the LVM homes in basic knowledge about ACT and on how to coach the participants.

Participants

Out of a total of 26 individuals who were recruited by the instructors, 18 participants fulfilled all enrollment data requirements. Inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: 1) ages 21–65 years, 2) diagnosed with a severe SUD according to ICD-10 and DSM-5 (no distinction was made between alcohol and drug use), and 3) institutionalized at an LVM home. Exclusion criteria were severe psychiatric symptoms, such as dementia or psychosis, which could interfere with the intervention. Four participants were excluded due to incomplete data: one was moved from the institution; one was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome and ADHD and excluded due to difficulties being in a group situation, one was incarcerated; and one escaped from the institution ().

Table 1 Demographic and diagnostic information for institutionalized participants with SUD (n = 18)

Table 2 Coding clinical scales and items into common assessment categories

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board of Stockholm, Sweden. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the study started.

Measures

Mental health status

To measure change in mental health scores between pre-intervention and post-intervention, the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – 21 (DASS-21),Citation35 a 21-item self-report measure designed to assess mental health, was used. Responses were reported on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time). High scores on the DASS-21 indicated a high level of depression, anxiety, or stress.

Psychological inflexibility

To measure change in psychological flexibility between pre-intervention and post-intervention, the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire – II (AAQ-II) was used, which is a modified version of the original AAQ,Citation36 which assesses experiential avoidance. It is currently the standard method of measuring psychological flexibility and measures nine aspects of executive function, utilizing 75 items across nine subscales.

Executive dysfunction

The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function – Adult Version (BRIEF-A)Citation10 is a self-assessment form measuring nine aspects of executive function, utilizing 75 items across nine subscales. The total score, the global executive composite (GEC), reflects overall functioning. The two summary index scales are the Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI), composed of four subscales (inhibition, shift, emotional control, and self-monitoring), and the Metacognition Index (MI), composed of five subscales (initiation, working memory, planning/organizing, task monitoring, and organization of materials). Each of the nine subscales is measured on a standardized T-scale according to the manual, for which a high score indicates high dysfunction. T-scores ≥65 are considered as clinically significant. The response format for items on the BRIEF-A is never, sometimes, and often.

Data collection

Data were collected pre intervention (1 day before the ACT intervention), after each session, and post-intervention (1 day after the ACT intervention). The DASS-21, AAQ-II, and BRIEF-A were administered pre-intervention and post-intervention. The AAQ-II was completed after each session during the entire intervention phase. Participants received gift cards with a value of $50.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed on the complete data (n=18) and on an individual level. Changes were assessed and described in the 13 clinical scales from pre-intervention to post-intervention. The individual results are the scores for the clinical scales assessing mental health (depression, anxiety, and stress), psychological flexibility, and executive function (i.e., four subscales of BRI and five subscales of MI). T-scores were available for the in-depth summary analysis of the executive functions, defined in the BRIEF-A manual.Citation10 In order to compare individuals on all the clinical scales, each subscale was recoded into a common 5-point categorical variable ranging from low low negative- to high high positive-labeled assessment categories defined in .

The cutoff points between categories were guided by available manuals, whereby the threshold for the high high positive (++) category corresponded to the normal/healthy category and the low low negative (−−) category to the most severe problem category.

The classification key – negative/status quo/positive trend – was developed to report substantial improvements rather than minor changes (see Notes in ).

Table 3 Summary of individual change between pre-intervention and post-intervention for all clinical scales

Results

Mental health

There was a balanced frequency distribution between negative change and positive change at an individual level. The majority of the participants reported no change in mental health ().

Psychological flexibility

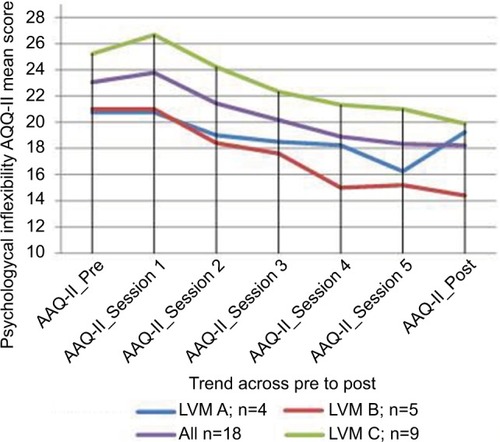

Psychological flexibility from 18 participants was assessed after every session, i.e., seven time points, and the results suggested a trend implying increased psychological flexibility across time and LVM home ().

Figure 1 Psychological inflexibility mean trends by LVM home for all participants (n=18).

Abbreviation: AAQ-II, Acceptance and Action Questionnaire – II.

At an individual level, suggests a trend implying improved psychological flexibility for twelve clients (67%) and that four clients maintained status quo and two moved in a negative direction.

Executive function

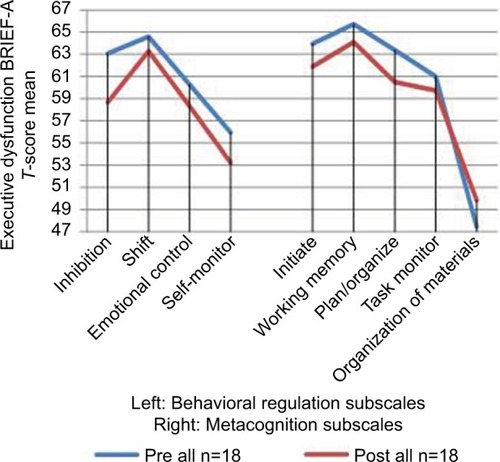

The mean T-scores () for all BRI subscales (inhibition, shift, emotional control, and self-monitor) appeared to be lower post-intervention, suggesting an increase in behavioral regulation. The subscale inhibition suggested the most positive change followed by self-monitor. T-score means on all MI subscales (initiate, working memory, plan/organize, task monitoring, and organization of materials), with the exception of organization of materials, appeared to decrease from pre-intervention to post-intervention. Within the MI subscales, the most positive outcome – according to T-score measures – was reported for plan/organize. Results for each of the nine subscales were measured on a standardized T-scale, for which a high score indicated high dysfunction.

Figure 2 Executive dysfunction mean T-score trends using the BRIEF-A subscales at pre- and post-intervention time points (n=18).

Abbreviation: BRIEF-A, Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function – Adult Version.

At an individual level, according to BRIEF-A scores, the most positive changes occurred in the subscale inhibition. As indicated, 8 participants reported a positive tendency, 10 participants maintained the status quo, and no participants showed a negative change (). Changes appeared to be positive for the emotional control subscale, i.e., six participants reported positive change, 10 maintained status quo, and two reported a negative change.

As reported in , the change between pre- intervention and post-intervention across all MI subscales was observed for task monitoring, where seven participants reported a positive tendency, eight participants maintained status quo, and three participants reported a negative change. For initiation, 5 participants reported a positive change, 12 showed no change, and 1 participant reported a negative change. It should be noted that T-score means are more affected by outliers than results based on assessment categories, making results from more reliable.

Correlations between psychological flexibility and executive function

Correlations between pre-intervention for psychological flexibility and post-intervention for executive function were calculated. Correlations ranged from 0.68 for emotional control to 0.86 for task monitoring. The results suggested correlations for inhibition (r=0.80) and initiation (r=0.78). While most of other subscale correlations were ~0.70, the index variables for BRI, MI, and GEC showed correlations of ~0.80.

Discussion

The aim of the present pilot study was to examine the effects of a 3-week, tailor-made, client-centered ACT intervention on mental health, psychological flexibility, and executive function of participants institutionalized for severe SUD.

The majority of the participants reported no change in mental health, which is in line with other studies implying that rehabilitation takes time and that there may be an “incubation effect”.Citation37,Citation38 There may be different reasons for this effect, one of which may be reactivity to DASS 21, rendering the participants more conscious of their sometimes tragic situation.

Concerning the number of change observations among the 18 participants outlined in for psychological flexibility and executive function, 31% (columns 7 and 8) implied an improvement across the 10 scales (AAQ and BRIEF-A), whereas 57% (column 6) remained status quo and 12% (columns 4 and 5) reported a negative change after a 3-week ACT intervention. More specifically, the changes in outcomes pre-intervention and post-intervention suggested that psychological flexibility had the most positive outcome, and also, executive functions implied a change in a positive direction across time, with the changes shown in inhibition, task monitoring, and emotional control. Since inhibition has been shown to have an association with SUDCitation39 and is an important process during rehabilitation, the result in the present pilot study suggesting a positive change in inhibition is hence promising. Substantial correlations were observed between psychological flexibility and executive functions, implying promise for more advanced causal modeling of data in future larger scale studies.

Limitations and implications

There are limitations that need to be mentioned. This pilot study was carried out without a matched control group, thus increasing the plausibility that factors, other than ACT, were influencing the results. To give an opinion on statistical significant results, the study would have required a much larger sample and resources; however, since these individuals constitute a multiproblematic target group (e.g., double diagnoses, homelessness, trauma, brain damage) being difficult to reach and to involve in research projects, a convenience sample was used. Hence, due to difficulties in involving the individuals in the study for a long period of time after the intervention, no measurements at later points in time were made, a consequence that makes the effects of ACT on the results only suggestive. The analyses were therefore descriptive, and there was no possibility of testing the observed effects of the intervention for statistical significance. Valid information about trends and improvement, however, was mapped in the follow-up data for participants and summarized in order to discern any changes. Although these data may be considered as anecdotal in nature, thus making inference difficult, understanding patterns of change after a short ACT intervention as a function of etiology and cognitive ability makes the importance of individual follow up all the more important. Individual follow-up provides information for optimizing individualized rehabilitation, a crucial strategy in this heterogeneous group.

Furthermore, there are also some threats to external validity that, for example, pertain to sample characteristics (to what extent the present findings can be generalized to other clients with SUD who vary in, e.g., social background, education, and age). Contextual characteristic (a novelty of ACT) and reactivity (special arrangements for the study) may also have had an influence on the present findings.

Results from earlier studies suggest, however, that ACT is a promising outpatient treatment model for SUD,Citation30 and the preliminary findings from the current study suggest that ACT may be a treatment worthy further investigation within an institutional context. To conclude, in order to gain research evidence from institutional settings, further development and implementation of ACT on a larger scale study, including the maintenance phase in the individual and follow-up long after the intervention, is needed.

Conclusion

The pilot study indicates that ACT can improve psychological flexibility and executive function. Clinical gains were achieved both at LVM home and at the individual level.

Since the sample size does not provide adequate statistical power to generalize and to draw firm conclusions concerning intervention effects, findings are descriptive and preliminary in nature. Further development and implementation of ACT on a larger scale study, including the maintenance phase and a follow-up, is needed.

Acknowledgments

This pilot study was conducted with support from the SiS. We want to thank SiS colleagues: Karin Pettersson, Ann Rundberg, Annie Josefsson, Madeleine Ritzman, and Tom Persson. We also want to thank Dr. Ola Schenström for his support with mindfulness practices, Professor Kelly Wilson for sharing pearls of wisdom, and Margot Trotter Davis, PhD, for assisting with her valuable expertise. Last, but not the least, we want to thank our wonderful participants who were our greatest inspiration and motivation.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GrantBFStinsonFSDawsonDAPrevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditionsArch Gen Psychiatry200461880781615289279

- HayesSCLevinMMindfulness and Acceptance for Addictive Behaviors. Applying Contextual CBT to Substance Abuse and Behavioral AddictionsOakland, CAContext Press2012

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th edWashington, DCAPA2013

- ErikssonAPalmJStorbjörkJKvinnor och män i svensk missbruksbehandling: En beskrivning av klientgruppen inom socialtjänstens missbrukarvård i Stockholms län 2001–2002. [Women and men in substance abuse care: A description of the client group in social services drug addiction in Stockholm 2001–2002]2003 Swedish

- RoehrsTRothTSleep, sleepiness, and alcohol useAlcohol Res Health200125210110911584549

- AdinoffBJunghannsKKieferFKrishnan-SarinSSuppression of the HPA axis stress-response: implications for relapseAlcohol Clin Exp Res20052971351135516088999

- HasinDSStinsonFSOgburnEGrantBFPrevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United StatesArch Genet Psychiatry2007647830842

- WilensTEMorrisonNRSubstance-use disorders in adolescents and adults with ADHD: focus on treatmentNeuropsychiatry20122430131223105949

- FeinGDi SclafaniVCardenasVAGoldmannHTolou-ShamsMMeyerhoffDJCortical gray matter loss in treatment-naive alcohol dependent individualsAlcohol Clin Exp Res20022655856411981133

- RothRMIsquithPKGioiaGABRIEF – A Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function – Adult VersionOdessa, FLPAR2005

- LawrenceAJLutyJBogdanNASahakianBJClarkLImpulsivity and response inhibition in alcohol dependence and problem gamblingPsychopharmacology2009207116317219727677

- LivheimFHayesLGhaderiAThe effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for adolescent mental health: Swedish and Australian Pilot OutcomesJ Child Family Stud20142410161030

- HayesSCLuomaJBBondFWMasudaALillisJAcceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomesBehav Res Ther200644112516300724

- HayesSCStrosahlKDWilsonKGAcceptance and Commitment Therapy The Process and Practice of Mindful Change2nd edNew York, NYGuilford2012

- HeffnerMEifertGHParkerBTHernandezDHSperryJAValued directions: acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of alcohol dependenceCognit Behav Prac200310378383

- PetersonCLZettleRDTreating inpatients with comorbid depression and alcohol use disorders: a comparison of acceptance and commitment therapy and treatment as usualPsychol Rec200959521536

- BattenBVHayesSCAcceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of comorbid substance abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder: a case studyClin Case Stud200543246262

- SmoutMFLongoMHarrisonSMinnitiRWickesWWhiteJMPsychosocial treatment for methamphetamine use disorders: a preliminary randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy and acceptance and commitment therapySubst Abus20103129810720408061

- TwohigMPShoenbergerDHayesSCA preliminary investigation of acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for marijuana dependence in adultsJ Appl Behav Anal200740461963218189094

- LuomaJBHayesSCKohlenbergGSubstance abuse and psychological flexibility: the development of a new measureAddict Res Theory2011191313

- BlackledgeJTDisrupting verbal processes: cognitive defusion in acceptance and commitment therapy and other mindfulness-based psychotherapiesPsychol Rec2007574555577

- BlackledgeJTCiarrochiJVDeaneFPAcceptance and Commitment Therapy Contemporary Theory, Research and PracticeBowen Hills, QLD, AustraliaAustralian Academic Press2009

- LuomaJBHayesSCWalserRDLearning ACT: An Acceptance & Commitment Therapy Skills-Training Manual for TherapistsOakland, CANew HarbingerReno, NVContext Press2007

- GioiaGAIsquithPKGuySKenworthyLBehavior rating inventory of executive functionChild Neuropsychol20006323523811419452

- StussDAlexanderMAffectively burnt in: a proposed role of the right frontal lobeMemory, consciousness, and the Brain: The Tallin ConferencePhiladelphiaPsychology Press2000

- GolemanDFocus: the Hidden Driver of ExcellenceNew York, NYHarperCollins2013

- GolemanD webpage on the InternetExercising the Mind to Treat Attention Deficits2014 Available from: http://nyti.ms/1gwioGQAccessed June 20, 2017

- LezakMDHowiesonDBLoringDWHannayHJFischerJSNeuropsychological AssessmentNew York, NYOxford University Press2004

- BradshawJLDevelopmental Disorders of the Frontostriatal SystemHove and New YorkPsychology Press/Taylor & Francis Group2001

- TangY-YHölzelBKPosnerMIThe neuroscience of mindfulness meditationNeuroscience201516421322525783612

- JhaAPKrompingerJBaimeMJMindfulness training modifies subsystems of attentionBehav Neurosci200772109119

- WilsonKGThe Wisdom to Know the Difference – An Acceptance & Commitment Therapy Workbook for Overcoming Substance AbuseOakland, CANew Harbinger Publications2012

- WilsonKGByrdMRAcceptance and commitment therapy for substance abuse and dependenceHayesSCStrosahlKA Practical Guide to Acceptance and Commitment TherapyNew York, NYSpringer Press2004153184

- SundquistJLiljaÅPalmérKMindfulness group therapy in primary care patients with depression, anxiety and stress and adjustment disorders: randomised controlled trialBr J Psychiatry2015206212813525431430

- BrownTAChorpitaBFKorotitschWBarlowDHPsychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samplesBehav Res Therapy19973517989

- BondFWHayesSCBaerRAPreliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological flexibility and acceptanceBehav Ther20114267668822035996

- ClarkeSKingstonJJamesKBolderstonHRemingtonBAcceptance and commitment therapy group for treatment-resistant participants: a randomized controlled trialJ Contextual Behav Sci201433179188

- LivheimFACT – Att hantera stress och främja hälsa. [To prevent stress and promote health]SwedenPrecens, Centrum för folkhälsa & Livheim2008 Swedish

- LawrenceAJLutyJBogdanNASahakianBJClarkLProblem gamblers share deficits in impulsive decision-making with alcohol-dependent individualsAddiction200910461006101519466924