Abstract

Substance-use disorders are a public health crisis globally and carry with them significant morbidity and mortality. Stigma toward people who abuse these substances, as well as the internalization of that stigma by substance users, is widespread. In this review, we synthesized the available evidence for the role of perceived social stigma and self-stigma in people’s willingness to seek treatment. While stigma may be frequently cited as a barrier to treatment in some samples, the degree of its impact on decision-making regarding treatment varied widely. More research needs to be done to standardize the definition and measurement of self- and perceived social stigma to fully determine the magnitude of their effect on treatment-seeking decisions.

Introduction

Alcohol-use disorders (AUDs) and drug-use disorders (DUDs) are issues of great concern to public health officials around the world. According to the World Drug Report, 31 million adult drug users across the globe suffer from a DUD, and the number of deaths from drug overdose has been rising.Citation1 Indeed, in the USA alone, deaths from overdoses of heroin or other opioids have quadrupled since 2010.Citation2 Although much of this trend is attributable to increases in the use of pharmaceutical opioids, legal substances, such as alcohol, are also problematic. Globally, 16% of individuals 15 years of age or older reported participating in episodes of heavy alcohol consumption in 2014, and 5.9% of all deaths that year were caused by alcohol use.Citation3 In the USA, 15.1 million adults over the age of 18 years had an AUD in 2015.Citation4

Despite the potentially lethal consequences of DUDs and AUDs, it has been estimated that fewer than one in six individuals worldwide receives treatment each year.Citation1 Within the USA, the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions estimated that rates of treatment seeking during the first year of disorder onset were 13% for drug dependence, 2% for drug abuse, 5% for alcohol dependence, and 1% for alcohol abuse.Citation5 Previous work has identified a number of treatment barriers that contribute to these low utilization rates. These barriers include systematic issues (ie, features endemic to the health care system), such as high costs of treatment, poor coordination among health care providers, inconvenient service hours, delays in access (ie, lengthy waiting times to see providers and lengthy waits for acceptance into treatment programs), and shortages of programs.Citation6–Citation13 Nonsystematic treatment barriers (ie, characteristics of individuals rather than the health care system) include denial of a problem,Citation8,Citation14–Citation16 lack of knowledge of treatment options,Citation6–Citation9 and dislike of available treatment options stemming either from doubts about the treatment model being offered or the perceived daily burden of participating in treatment.Citation6 Perceived burden is a particularly common complaint among opioid users in methadone maintenance treatment, which requires a daily time commitment to participate successfully.Citation17

One type of barrier that is believed to be particularly impactful for those in need of treatment for AUDs and DUDs is stigma. Stigma is a complex construct that can come from many sources and may manifest as a barrier in several ways. Perceived social stigma is one type of stigma in which a person recognizes and believes that their society holds prejudicial beliefs that will result in discrimination against them.Citation18 Perceived social stigma can act as a systematic barrier when those to whom substance users turn for help (eg, primary-care providers) react with negative judgments and even disgust. Indeed, there is evidence not only that primary-care providers do not feel prepared to deliver appropriate care to those with substance-use issues, such as AUD and DUD,Citation19 but also that health care professionals in general may have negatively biased views of these individuals that include beliefs that such individuals are violent, manipulative, and poorly motivated to change.Citation20 Such reactions to substance users may be so subtle that they are felt by the substance user, but are otherwise ineffectual, or they may be accompanied by more direct disparities in care (eg, differential care patterns after acute myocardial infarction).Citation21 These attitudes may also directly impact the behaviors of drug and alcohol users, as research has shown that individuals who experience discrimination are much more likely to engage in behaviors that are harmful to their health.Citation22 Finally, perceived social stigma may become internalized and result in self-stigma (ie, the personal endorsement of stereotypes about oneself and the resulting prejudice and self-discrimination).Citation18

Various types of stigma can also act as nonsystematic barriers. Public stigma against substance abuse is commonCitation23 and can deter people with a variety of mental health conditions, including substance-related conditions, from seeking help, due to feelings of embarrassment or shame.Citation1,Citation5,Citation16 Self-stigma can also deter treatment when it results in loss of self-respect and questioning the point of trying to get better.Citation24 At least one review has found that attitudinal barriers, a category including stigma, were more important in predicting nontreatment than financial barriers.Citation25 However, note that this review was limited in scope to papers produced from one nationwide longitudinal study, while there have been a number of other studies that have examined this issue. The purpose of the current paper is to provide a broader review of the literature examining the impact of perceived social stigma and self-stigma on treatment-seeking decisions, including expressed desire to enter treatment.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic search of the literature was carried out to identify articles related to perceived social stigma and self-stigma related to seeking treatment for AUDs and DUDs. The PubMed, Scopus, and PsycInfo databases were searched first in September 2016. Our initial search used the following terms: (“social stigma” OR self-stigma) AND (dependence, addiction, OR abuse). We then expanded our PubMed search by adding the MeSH terms “shame” and “substance-related disorders”, producing the following search string: (“shame” [MeSH] OR “social stigma” OR self-stigma OR stigma) AND “substance-related disorders” (MeSH). We then also expanded our PsycInfo and Scopus searches to the following: (shame OR “social stigma” OR self-stigma OR stigma) AND “substance-related disorders” OR “drug abuse” OR “drug dependence” OR “alcohol abuse” OR “alcohol dependence” OR addiction OR “substance abuse”. References identified within publications and thought to be relevant were added to the corpus of articles for further screening. Due to the time lapse between the initial search and finalization of the manuscript, the search was repeated on July 27, 2018.

Selection of literature

After discarding of duplicates and articles not available in English (due to lack of translation resources), at least two people examined the title and abstract of each article for relevance to the review questions. Next, the bodies of the remaining papers were reviewed. Opinion pieces, conference abstracts, case reports, case series, commentaries, and review articles or book chapters without original research reported were excluded, as were studies that did not have people who used psychoactive substances as subjects or that did not explicitly link social or self-stigma to treatment seeking. We included articles that were original empirical work and explicitly linked stigma (of any type, as terminology varied or was vague in many studies, ie, did not specify a type of stigma) or stigma-like constructs (ie, shame,Citation1 embarrassment, need for secrecy) to either the desire to seek treatment or actually seeking treatment for alcohol or drug use. Stigma-like constructs were included because in many articles stigma was a loosely defined concept that was discussed in terms of being ashamed or embarrassed for others to find out about problematic drug or alcohol use, but not necessarily precisely worded during measurement. We also included both articles that specified diagnoses of AUD or DUD and those that referenced problematic alcohol or drug use in the absence of an official diagnosis. We did not screen articles based on the legality of the substance. We did exclude studies that looked solely at nicotine dependence, as this was not the target of this review. Because we aimed to be as inclusive as possible, we did not exclude articles based on quality of evidence, but rather critiqued articles as appropriate in our analysis.

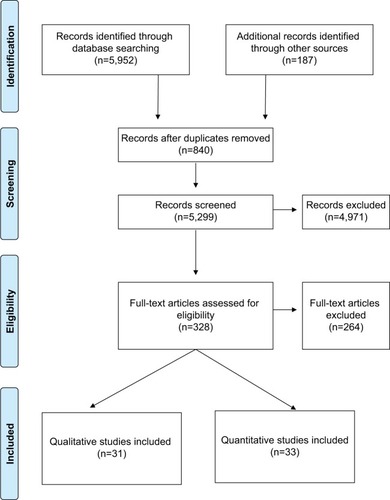

All authors participated in initial screening before the primary author and KC reviewed them again to ensure completeness. Disagreements, if any, were resolved through discussion and consensus. The PRISMA flowchart for selection of articles is shown in .

Data extraction

and contain overall summaries of all articles. For each article, we extracted reference information, location, sample size, participant demographics, relevant constructs measured in the study, and results relevant to this review. For qualitative articles (), we extracted analysis approach, while for quantitative articles (), we extracted construct-measurement tools.

Table 1 Summary of characteristics of included qualitative publications related to treatment seeking

Table 2 Summary of characteristics of included quantitative publications related to treatment seeking

Results

illustrates the literature-identification and -screening process. Of 6,139 articles considered, 64 were included in the final review. A total of 31 qualitative articles are summarized in , and 33 quantitative articles are summarized in . Note that “perceived stigma” is based upon subjective reports, and thus does not bear on this issue of whether or not such stigma was objectively present. Also of note, the etiology of reports of stigma from health care professionals could be debated as a version of structural stigma, the process of institutions having a culture of stigmatizing policies and practices (with employees representing the policies and attitudes of the places in which they work), or public stigma (with their attitudes representing their own core beliefs). We chose to interpret it as the latter, and instances of this are noted as perceived health care-professional stigma, a subset of perceived social stigma, in the tables. Not all studies used the exact constructs of self-stigma or perceived social stigma in their work. However, the constructs we included were those that were most closely related to these types of stigma and measured some aspect of one or the other.

Qualitative stigma experiences

A number of qualitative studies (see ) have provided an overview of the stigma experiences of those in need of treatment for substance abuse. Feelings of shame,Citation26–Citation28 embarrassment,Citation26,Citation29,Citation30 and guiltCitation26 were reported. Problem substance users also reported a need for secrecy about both their use and any attempts to seek treatment.Citation27,Citation28,Citation31 This secrecy was linked to perceptions of stigma from health care providers in general practice and emergency settings, who may be the first source of help available, and thus the need for secrecy was said to lead to delays in treatment seeking.Citation29–Citation33 Two studies suggested that these feelings and need for secrecy stemmed from a strong desire to avoid accepting the identity of “addict” or “junkie”,Citation34,Citation35 while two more found that even those who had attempted to seek treatment may disengage when identity conflicts arise.Citation17,Citation36 On the other hand, participants in one study said they had sought help from a general practitioner specifically to avoid stigma from social sources,Citation33 while those in other studies said that emotional support from loved ones had facilitated seeking formal help for substance abuse.Citation37,Citation38

Frequency of stigma as a barrier

Of the 33 quantitative studies summarized in , 23 shed light on the frequency with which stigma was perceived as a barrier to treatment relative to other barriers. Stigma-as-barrier frequencies ranged from just 2%Citation39 up to 92%Citation40 (mean 30.39%, SD 19.46%). Using 50% frequency as a cutoff to differentiate between high (≥50%) and low (<50%) stigma-frequency studies, only fourCitation40–Citation43 fall into the high-frequency category (mean 67.00%, SD 11.37%). All these high-frequency studies were cross-sectional. Among the low-frequency studies (mean 31.33%, SD 19.99%), three reported high stigma frequencies in certain subsets of their sample.Citation7,Citation44,Citation45 Bisexuals (compared to heterosexual and homosexual,Citation44 but see also Green,Citation42 who found heterosexuals reported stigma more often than homosexual and bisexual individuals), people with many barriers (compared to few barriers),Citation45 and alcohol users (compared to drug users)Citation7 all reported stigma as a barrier >50% of the time, whereas their comparison groups did not. In a primarily qualitative study of illicit-stimulant users, less than half had entered drug-abuse treatment and most did not feel they needed help; social stigma was cited only by a few as a barrier to treatment.Citation46 The remaining 16 studies all reported low frequencies for stigma (mean 18.99, SD 8.59). These studies were both longitudinal (n=10) and cross-sectional (n=6).

Relative to other barriers, the frequencies reported in the 23 studies put stigma (or stigma-relevant constructs) in ordinal ranks ranging from most to 13th-most frequently reported (see ). Overall, stigma (or a stigma-like construct) was in the top-three most frequent barriers in 17 studies. These studies also reported the frequencies of other treatment barriers. “Should handle alone” was the most frequent barrier in seven studies,Citation8,Citation13,Citation14,Citation44,Citation45,Citation47,Citation48 stigma (or stigma-relevant constructs) in six studies,Citation7,Citation39–Citation41,Citation43,Citation49 denial of a problem in five,Citation13,Citation39,Citation42,Citation50,Citation51 “not ready to quit” in three,Citation10,Citation12,Citation52 cost and access barriers in four,Citation10–Citation12,Citation53 role responsibilities in two,Citation44,Citation54 and treatment attitudes in one.Citation11 Note that barriers tied for most frequent in several studies, and that the rank order of barriers often varied by participant group (eg, men vs women). See for more details.

Table 3 Summary of barrier frequency rankings in articles with frequency data

Only five qualitative articles in reported frequency of stigma as a barrier, ranging from 15%Citation55 to 90%Citation56 (mean 55.75%, SD 29.90). The highest frequency was from a study where stigma was associated with a national drug-user registration system that led to lifelong consequences.Citation56 The second-highest frequency, 78% for female substance users, actually reflects the number of women who felt compounded stigma for being both female and a user.Citation6 The remaining three frequencies were <50%,Citation55,Citation57,Citation58 and one of these duplicates data from an article in and .Citation54,Citation55

Degree of influence of stigma

In addition to frequency, three quantitative studies directly asked participants to rate the degree of influence stigma had on their decisions about treatment seeking. In the first, mean ratings (on a scale from 1 [not influential] to 5 [very influential]) were 3.7 for alcohol users and 3.4 for drug users.Citation7 These values were the seventh- (for alcohol users) and eighth- (for drug users) highest influence ratings: the most influential barrier for alcohol users was being unaware of treatment options, while for drug users it was being in denial of a problem. In the second study, the mean stigma-influence rating for alcohol users was 0.72 (on a scale from 0 [not influential] to 3 [very influential]), with stigma being the third-most influential barrier of nine.Citation42 In this study, denial of a problem was the most influential barrier. Finally, the third study found that problem drinkers’ mean stigma-influence rating was 2.7 (on a scale from 1 [not influential] to 5 [very influential]), with stigma being the most influential of six barriers.Citation43

Stigma as a statistical predictor of treatment

Twelve studies that did not ask participants to rate directly the influence of stigma on their treatment-seeking decisions did use statistical methods to determine whether or not stigma predicted treatment motivation and/or utilization.Citation13,Citation15,Citation42,Citation54,Citation59–Citation66 Of these, five found stigma to be a positive predictor or copredictor,Citation54,Citation60,Citation63–Citation65 three found it to be a negative predictor or copredictor,Citation15,Citation61,Citation62 and three found it not to be a predictor at all.Citation13,Citation42,Citation59

The first study that found stigma to be a positive predictor found that stigma barriers significantly predicted treatment utilization at 3-month follow-up for cocaine users seen in the emergency room, while other types of treatment barriers did not.Citation60 The second study found that pregnant women in a detoxification program who reported an acceptability barrier (a category that included stigma) had increased treatment-motivation scores, while gestational age of the fetus was a negative predictor.Citation54 The third and fourth studies were different analyses of the same data. The third study found stigma consciousness to be a positive predictor of current treatment utilization for women only,Citation64 while the fourth found it to be a significant positive predictor for “colored” participants only.Citation63 The final study found that person-related barriers (a category that included stigma, but also “wanting to handle the problem on your own” and not having motivation or reasons to stop drinking) positively predicted currently being in treatment. Sex and education level were also positive predictors, while intrapersonal consequences and emotional distress were negative predictors.Citation65

The first study that found stigma to be a negative predictor found that higher alcohol-related stigma (controlling for disorder severity, sex, age, race, ethnicity, income, education, and marital status) was related to less lifetime use of any treatment option.Citation15 The second study found that drug stigma was related only to 12-month treatment utilization in those who also had high HIV stigma.Citation61 The third study was conducted with psychology students, and found that more stigma was related to less interest in seeking help.Citation62

Finally, one study that did not find stigma to be a significant predictor found that alcohol-related stigma did not predict treatment seeking 1 year later.Citation13 A second study found that alcohol-related stigma was related to race, but that race did not predict treatment seeking 1 year later.Citation59 The third study grouped stigma with all perceived barriers, and found it did not predict having a history of treatment use.Citation42

Compounding effects of multiple stigmas

A total of 29 studies reported on the combined effects of multiple stigmas on treatment-seeking decisions.Citation6,Citation8,Citation11,Citation12,Citation30,Citation37,Citation39,Citation41,Citation44,Citation45,Citation50,Citation55–Citation57,Citation59,Citation61,Citation63,Citation64,Citation67–Citation78 Generally speaking, individuals with more barriers to treatment were found to be less likely to seek treatment than those with fewer barriers in one study.Citation45 More specifically, participants across various studies reported compounded effects on treatment decisions of being both substance users and older,Citation57,Citation67 a member of a racial or ethnic minority,Citation8,Citation50,Citation59,Citation64,Citation68,Citation69 HIV-positive,Citation61 dually diagnosed with depression,Citation11 or female.Citation6,Citation30,Citation37,Citation50,Citation54,Citation56,Citation64,Citation70–Citation74 Females in several studies had a number of additional stigmas, including that of being pregnant,Citation54 incarcerated,Citation72 or black.Citation74 Stigmas were particularly influential on women when their substance use and/or usage of treatment services had implications for child-custody arrangements.Citation30,Citation37 Other institutional influences also increased the influence of stigma. Studies in countries with drug-user registries showed that fears of the consequences of the registration process affected decisions to seek treatment for many.Citation50,Citation56,Citation75,Citation76 Country of origin also impacted the influence of stigma in the absence of such programs, likely via social and cultural expectations.Citation39 Additionally, sexual orientation (bisexuality compared to homo- and heterosexuality)Citation44 and some chosen careers (nursing and army soldiers)Citation41,Citation77,Citation78 increased the influence of stigma in some studies.

Congruently with these findings, a study that did not specifically measure multiple stigmas, but did look at the ability of demographic variables to predict treatment use longitudinally, found that being a woman, a minority, married, college-educated, employed, and having a higher income all decreased the odds of having sought treatment in the past year.Citation12

Discussion

The articles reviewed here provide a mixed picture as to the influence of stigma on treatment decisions in those with a need for treatment for alcohol or drug use. Seventy percent of quantitative studies that provided frequency information for stigma as a treatment barrier reported low rates, with stigma ranging between the most and 13th-most frequently cited barrier. All studies reporting high frequency for stigma were cross-sectional and thus incapable of prospective prediction of treatment utilization, whereas ten of the studies with low frequency were longitudinal in nature.

That said, frequency itself is not necessarily the variable of most interest. A barrier might occur only in a small number of people and yet be highly influential for those individuals. Only three studies in this review asked participants to rate the influence of stigma on their treatment-seeking decisions: in these, stigma ranged from the most influential to eighth-most influential barrier. The study where stigma was rated as most influential included only 39 alcohol users,Citation43 while the other two studies included 218Citation42 and 346 individuals.Citation7 With so few studies, such low sample sizes, and such mixed findings of influence strength, it is unwise to make strong claims about the ultimate influence of stigma on treatment decisions in the larger population of substance users.

Statistical prediction of treatment utilization also showed mixed results in the studies reviewed. Five studies found that stigma was a positive predictor or copredictor, three that it was negative predictor or copredictor, and three that it was not a predictor at all. Of the positive (co)predictor studies, two looked at stigma within a larger category of barriers,Citation54,Citation65 two probed the stigma of being a user (as opposed to the stigma of getting into treatment),Citation63,Citation64 and one looked at individuals who had experienced a significant health event related to their use.Citation60 It stands to reason that measuring stigma within a larger category loses some specificity in terms of the direct impact of stigma on treatment-seeking decisions. Additionally, probing stigma of use is quite different from probing the stigma of getting treatment. It is easy to understand why someone might feel pressure to get help if it were known they had a problem with drugs or alcohol, whereas due to secretive coping strategies, many users may actually be able to maintain a degree of privacy concerning their use that would be lost by seeking treatment. Therefore, this collection of studies does not provide strong evidence of a positive influence of stigma on treatment seeking.

In terms of negative (co)predictor studies, the first was cross-sectional data from a longitudinal study.Citation15 Another article from the same longitudinal study, but using two waves of data, found that stigma was not a predictor of treatment use,Citation13 calling into question the utility of cross-sectional data in assessing this relationship. The second negative study found stigma was influential only when present for two statuses (ie, user and HIV-positive),Citation61 supporting the idea that confounded multiple stigmas may be highly influential, but not providing good evidence of a singular effect of substance-related stigma. Finally, the third negative study was conducted in college students (as opposed to a sample of only those with substance-use disorders) and measured only “help-seeking interest”, not actual use of services,Citation62 making this study a measure of theoretical attitudes, rather than actual behavior in a population in need of treatment. As such, these studies are not particularly convincing either.

Of the studies that found no relationship between treatment seeking and stigma, two were longitudinalCitation13,Citation59 and one was not.Citation42 One of the longitudinal studies only looked at stigma as a predictor indirectly through its relationship to race,Citation59 and the cross-sectional study grouped stigma with all perceived barriers to treatment.Citation42 The remaining longitudinal studyCitation13 is somewhat more convincing, in that it is a report from a nationwide study and contains two waves of data. On balance, however, this group of studies is no more convincing than those that found a relationship between stigma and treatment-seeking decisions.

On more steady ground is the finding that multiple stigmas together can have compounded influence on treatment-seeking decisions. Thirty studies (47%) found evidence of the increased influence of compounded stigmas or a relationship between stigmatized demographic variables (ie, being a woman or minority) and treatment-seeking decisions. However, recognition of this fact may have contributed to the development of more culturally appropriate treatment programs for people with these compounded stigmas,Citation79 and thus the gap for sex and racial groups to access care, while still present, may have narrowed in recent years.Citation80

The mixed results reported in this review are somewhat disheartening, given the number of studies included. However, as previously alluded to, one major factor in this problem is likely related to varying definitions and measurement of the constructs of interest. Stigma is a complex construct, and is thus difficult to define and measure. There are different sources of stigma, including social institutions, public opinion, and the self. Moreover, these sources are all interconnected. For example, self-stigma is thought to develop as external stigma internalized by the individual.Citation81 It is also the case that stigma can range from extremely subtle perceptions, which themselves may arise from objectively observable external sources or from subjective inner perceptions, to blatant discrimination practices. In terms of drug and alcohol use, there are also different targets of the stigma: there is the stigma of being a user itself, there is the entirely separate stigma of being someone who needs help with their use, which is activated when one seeks treatment services, and there is differentiated stigma, depending on the substance being used.Citation82 Finally, there is also the problem of multiple compounded stigmas. Many people who fall into one stigmatized category (eg, drug user) also fall into other such categories (eg, incarcerated individual, bisexual, female). Locating the boundary between one stigma and the next is difficult, if not impossible, and thus their impact must often be assessed together, rather than individually.

Beyond simply defining stigma, researchers have measured it in a number of ways, making it somewhat difficult to pull all the literature together coherently. Some measured stigma within a larger category (eg, acceptability of treatment), some measured one type or the other (eg, social stigma vs self-stigma) alone, others measured components of stigma that they had defined in various ways (eg, perceived devaluation), and still others measured stigma-related concepts (eg, fear of what others think or embarrassment). This lack of standardization must be considered when attempting to determine why one study may find a relation between (whatever they are calling) stigma and treatment seeking, while another does not. A secondary consequence is that there are not a large number of studies with the same measure of stigma to aggregate in a meta-analysis, which would be the best way to determine the strength of the evidence for any effect.

In addition to the complexity in defining and measuring stigma, there is the complexity of human motivation to consider. In a number of studies, the most frequently cited reasons not to seek treatment were not being ready to stop using,Citation10,Citation12,Citation52 not accepting that there was a problem with use,Citation13,Citation39,Citation42,Citation50,Citation51 or other attitudes about treatment.Citation8,Citation11,Citation14,Citation44,Citation45,Citation47,Citation48 Stages of readiness to change must be considered when looking at the impact of stigma,Citation60,Citation62,Citation83 as it stands to reason that someone who does not recognize they have a problem with drug or alcohol use at all will not be particularly influenced by perceived stigma against substance-use treatment, as the idea of getting treatment does not enter their consciousness. In other words, if one wishes to measure the influence of stigma on treatment seeking, first one must know where the sample falls in terms of problem recognition. Indeed, modern substance-use-treatment approaches are centered on the stages-of-change model.

Another factor to consider is treatment history. NotleyCitation33 suggests that studies in this area should consider those who have a previous treatment history separately from those who have not. Having been through the process before exposes one to actual experiences of various types of stigma, as opposed to the anticipation of stigma in those who have not yet sought any treatment. Indeed, veterans who had attended at least nine mental health-treatment sessions had higher stigma scores than those who had not,Citation84 a finding that one might reasonably suspect would be relevant in the case of drug- and alcohol-use treatment. Therefore, stigma may have a different level of influence in each population. Relatedly, a common theme in a number of studies in this review was that the source of stigma matters. In particular, it seems that nonjudgmental acceptance from staff at health care and substance-treatment facilities might be instrumental in overcoming negative emotions, self-stigma, and perceived social stigma associated with treatment, whereas staff who propagate stigma in populations with drug- or alcohol-use problems discourage these individuals from seeking or remaining in treatment.

In summary, this review of the literature found that while stigma may be frequently cited as a barrier to treatment in some samples, it is unclear if it is a particularly influential one. Clearly in some cases it is highly influential, such as when multiple stigmas are compounded, or when the stigma is being experienced or anticipated from staff at rehabilitation facilities or programs. But there are also clearly times when stigma is not the main concern, most especially when the user does not recognize their use as problematic. In a similar vein, sometimes stigma is not perceived as such directly, but can be seen in indirect ways (eg, worried about what others will think, feelings of embarrassment). Without concentrated efforts to standardize the definition and measurement, the exact magnitude of the effect of stigma on treatment-seeking decisions, if any, will almost certainly remain unknown.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Richard Vath, MA, for his invaluable help in the conceptualization and early organization of the paper.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Drug Report 2018 (United Nations publication SNEX) Available from: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018Accessed July 3, 2018

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionNational Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. Heroin Overdose Data Updated January 26, 2017 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/heroin.htmlAccessed May 21, 2017

- ChestnovOGlobal Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2014SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2014

- (SAMHSA) SAaMHSA2015National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Table 5.6A – Substance Use Disorder in Past Year among Persons Aged 18 or Older, by Demographic Characteristics: Numbers in Thousands, 2014 and 20152015 Available from: https://www.samhsagov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015htm#tab5-6bAccessedNovember 12, 2018

- BlancoCIzaMRodríguez-FernándezJMBaca-GarcíaEWangSOlfsonMProbability and predictors of treatment-seeking for substance use disorders in the U.SDrug Alcohol Depend201514913614425725934

- CopelandJA qualitative study of barriers to formal treatment among women who self-managed change in addictive behavioursJ Subst Abuse Treat19971421831909258863

- CunninghamJASobellLCSobellMBAgrawalSToneattoTBarriers to treatment: why alcohol and drug abusers delay or never seek treatmentAddict Behav19931833473538393611

- GrantBFBarriers to alcoholism treatment: reasons for not seeking treatment in a general population sampleJ Stud Alcohol19975843653719203117

- McCutcheonJMMorrisonMAInjecting on the Island: a qualitative exploration of the service needs of persons who inject drugs in Prince Edward Island, CanadaHarm Reduct J20141111024593319

- AliMMTeichJLMutterRReasons for not seeking substance use disorder treatment: variations by health insurance coverageJ Behav Health Serv Res2017441637427812852

- ChenLYStrainECCrumRMMojtabaiRGender differences in substance abuse treatment and barriers to care among persons with substance use disorders with and without comorbid major depressionJ Addict Med20137532533424091763

- ChoiNGDinittoDMMartiCNTreatment use, perceived need, and barriers to seeking treatment for substance abuse and mental health problems among older adults compared to younger adultsDrug Alcohol Depend201414511312025456572

- MojtabaiRCrumRMPerceived unmet need for alcohol and drug use treatments and future use of services: results from a longitudinal studyDrug Alcohol Depend20131271–3596422770461

- CohenEFeinnRAriasAKranzlerHRAlcohol treatment utilization: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related ConditionsDrug Alcohol Depend2007862–321422116919401

- KeyesKMHatzenbuehlerMLMcLaughlinKAStigma and treatment for alcohol disorders in the United StatesAm J Epidemiol2010172121364137221044992

- CummingCTroeungLYoungJTKeltyEPreenDBBarriers to accessing methamphetamine treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysisDrug Alcohol Depend201616826327327736680

- RadcliffePStevensAAre drug treatment services only for ‘thieving junkie scumbags’? Drug users and the management of stigmatised identitiesSoc Sci Med20086771065107318640760

- CorriganPWRaoDOn the self-stigma of mental illness: stages, disclosure, and strategies for changeCan J Psychiatry201257846446922854028

- MillerNSSheppardLMColendaCCMagenJWhy physicians are unprepared to treat patients who have alcohol- and drug-related disordersAcad Med200176541041811346513

- van BoekelLCBrouwersEPvan WeeghelJGarretsenHFStigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic reviewDrug Alcohol Depend20131311–2233523490450

- LiYGlanceLGLynessJMCramPCaiXMukamelDBMental illness, access to hospitals with invasive cardiac services, and receipt of cardiac procedures by Medicare acute myocardial infarction patientsHealth Serv Res20134831076109523134057

- RichmanLSLattannerMRSelf-regulatory processes underlying structural stigma and healthSoc Sci Med20141039410024507915

- RoomRRehmJPagliaAUstunTBCross cultural views on stigma, valuation, parity, and societal views towards disabilityUstunTBDisability and cultureSeattleHogrefe & Huber Publishers2001247291

- CorriganPWBinkABSchmidtAJonesNRüschNWhat is the impact of self-stigma? Loss of self-respect and the “why try” effectJ Ment Health2016251101526193430

- HasinDSGrantBFThe National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Waves 1 and 2: review and summary of findingsSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol201550111609164026210739

- JakobssonAHensingGSpakFThe role of gendered conceptions in treatment seeking for alcohol problemsScand J Caring Sci200822219620218489689

- FinnSWBakshiASAndréassonSConsumptionAAlcohol consumption, dependence, and treatment barriers: perceptions among nontreatment seekers with alcohol dependenceSubst Use Misuse201449676276924601784

- WieczorekŁBarriers in the access to alcohol treatment in outpatient clinics in urban and rural communityPsychiatr Pol201751112513828455900

- HaightonCWilsonGLingJMcCabeKCroslandAKanerEA Qualitative study of service provision for alcohol related health issues in mid to later lifePLoS One2016112e014860126848583

- NealeJTompkinsCSheardLBarriers to accessing generic health and social care services: a qualitative study of injecting drug usersHealth Soc Care Community200816214715418290980

- DysonJExperiences of alcohol dependence: a qualitative studyJ Fam Health Care200717621121418201015

- KozloffNCheungAHRossLEFactors influencing service use among homeless youths with co-occurring disordersPsychiatr Serv201364992592824026839

- NotleyCMaskreyVHollandRThe needs of problematic drug misusers not in structured treatment – a qualitative study of perceived treatment barriers and recommendations for servicesDrugs20121914048

- GilchristGMoskalewiczJNuttRUnderstanding access to drug and alcohol treatment services in Europe: a multi-country service users’ perspectiveDrugs2014212120130

- KhadjesariZStevensonFGodfreyCMurrayENegotiating the ‘grey area between normal social drinking and being a smelly tramp’: a qualitative study of people searching for help online to reduce their drinkingHealth Expect20151862011202025676536

- GourlayJRicciardelliLRidgeDUsers’ experiences of heroin and methadone treatmentSubst Use Misuse200540121875188216419562

- GuetaKA qualitative study of barriers and facilitators in treating drug use among Israeli mothers: an intersectional perspectiveSoc Sci Med201718715516328689089

- McCannTVMugavinJRenzahoALubmanDISub-Saharan African migrant youths’ help-seeking barriers and facilitators for mental health and substance use problems: a qualitative studyBMC Psychiatry201616127527484391

- ProbstCMantheyJMartinezARehmJAlcohol use disorder severity and reported reasons not to seek treatment: a cross-sectional study in European primary care practicesSubst Abuse Treat Prev Policy20151013226264215

- StepanyanKMethamphetamine Users and Gender Differences in their Acceptance of Long-Term Substance Abuse Treatment ProgramsCollege of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Walden University2016 Available from: http://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertationsAccessed November 7, 2018

- CaresAPaceEDeniousJCraneLASubstance use and mental illness among nurses: workplace warning signs and barriers to seeking assistanceSubst Abus2015361596625010597

- GreenKEClient-Guided Treatment Development for Problem Drinkers of Various Sexual OrientationsNew Brunswick, NJDepartment of Psychology, Rutgers University2008

- TuckerJAVuchinichREGladsjoJAEnvironmental events surrounding natural recovery from alcohol-related problemsJ Stud Alcohol19945544014117934047

- AllenJLMowbrayOSexual orientation, treatment utilization, and barriers for alcohol related problems: findings from a nationally representative sampleDrug Alcohol Depend201616132333026936411

- SchulerMSPuttaiahSMojtabaiRCrumRMPerceived barriers to treatment for alcohol problems: a latent class analysisPsychiatr Serv201566111221122826234326

- SextonRLCarlsonRGLeukefeldCGBoothBMBarriers to formal drug abuse treatment in the rural south: a preliminary ethnographic assessmentJ Psychoactive Drugs200840212112918720660

- HingsonRMangioneTMeyersAScotchNSeeking help for drinking problems; a study in the Boston Metropolitan AreaJ Stud Alcohol19824332732887120998

- van der PolPLiebregtsNde GraafRKorfDJvan den BrinkWvan LaarMFacilitators and barriers in treatment seeking for cannabis dependenceDrug Alcohol Depend2013133277678024035185

- PalHRYadavSJoyPSMehtaSRayRTreatment nonseeking in alcohol users: a community-based study from North IndiaJ Stud Alcohol200364563163314572184

- ZemoreSEMuliaNYuYeBorgesGGreenfieldTKGender, acculturation, and other barriers to alcohol treatment utilization among Latinos in three National Alcohol SurveysJ Subst Abuse Treat200936444645619004599

- GatesPCopelandJSwiftWMartinGBarriers and facilitators to cannabis treatmentDrug Alcohol Rev201231331131921521384

- WuLTBlazerDGLiTKWoodyGELtWTkLTreatment use and barriers among adolescents with prescription opioid use disordersAddict Behav201136121233123921880431

- MojtabaiRChenLYKaufmannCNCrumRMComparing barriers to mental health treatment and substance use disorder treatment among individuals with comorbid major depression and substance use disordersJ Subst Abuse Treat201446226827323992953

- JacksonAShannonLExamining barriers to and motivations for substance abuse treatment among pregnant women: does urban-rural residence matter?Women Health201252657058622860704

- JacksonAShannonLBarriers to receiving substance abuse treatment among rural pregnant women in KentuckyMatern Child Health J20121691762177022139045

- BobrovaNRhodesTPowerRBarriers to accessing drug treatment in Russia: a qualitative study among injecting drug users in two citiesDrug Alcohol Depend200682Suppl 1S57S6316769447

- AyresRMEvesonLIngramJTelferMTreatment experience and needs of older drug users in Bristol, UKJ Subst Use20121711931

- NaughtonFAlexandrouEDrydenSBathJGilesMUnderstanding treatment delay among problem drinkers: what inhibits and facilitates help-seekingDrugs2013204297303

- SmithSMDawsonDAGoldsteinRBGrantBFExamining perceived alcoholism stigma effect on racial-ethnic disparities in treatment and quality of life among alcoholicsJ Stud Alcohol Drugs201071223123620230720

- FortneyJCTripathiSPWaltonMACunninghamRMBoothBMPatterns of substance abuse treatment seeking following cocaine-related emergency department visitsJ Behav Health Serv Res201138222123320700660

- CalabreseSKBurkeSEDovidioJFInternalized HIV and drug stigmas: interacting forces threatening health status and health service utilization among people with HIV who inject drugs in St. Petersburg, RussiaAIDS Behav2016201859726050155

- CellucciTKroghJVikPHelp seeking for alcohol problems in a college populationJ Gen Psychol2006133442143317128960

- MyersBBarriers to alcohol and other drug treatment use among Black African and Coloured South AfricansBMC Health Serv Res201313117723683119

- MyersBLouwJPascheSGender differences in barriers to alcohol and other drug treatment in Cape Town, South AfricaAfr J Psychiatry2011142146153

- SaundersSMZygowiczKMD’AngeloBRPerson-related and treatment-related barriers to alcohol treatmentJ Subst Abuse Treat200630326127016616171

- SempleSJGrantIPattersonTLUtilization of drug treatment programs by methamphetamine users: the role of social stigmaAm J Addict200514436738016188717

- ConnerKORosenD“You’re nothing but a junkie”: multiple experiences of stigma in an aging methadone maintenance populationJ Soc Work Pract Addict200882244264

- BrowneTPriesterMACloneSIachiniADehartDHockRBarriers and facilitators to substance use treatment in the rural south: a qualitative studyJ Rural Health20163219210126184098

- SmyeVBrowneAJVarcoeCJosewskiVHarm reduction, methadone maintenance treatment and the root causes of health and social inequities: an intersectional lens in the Canadian contextHarm Reduct J2011811721718531

- GunnAGuarinoH“Not human, dead already”: perceptions and experiences of drug-related stigma among opioid-using young adults from the former Soviet Union living in the U.S.Int J Drug Policy201638637227855325

- OtiashviliDKirtadzeIO’GradyKEAccess to treatment for substance-using women in the Republic of Georgia: socio-cultural and structural barriersInt J Drug Policy201324656657223756037

- van OlphenJEliasonMJFreudenbergNBarnesMNowhere to go: how stigma limits the options of female drug users after release from jailSubst Abuse Treat Prev Policy2009411019426474

- SmallJCurranGMBoothBBarriers and facilitators for alcohol treatment for women: are there more or less for rural women?J Subst Abuse Treat201039111320381284

- JonesLVHopsonLWarnerLHardimanERJamesTA qualitative study of black women’s experiences in drug abuse and mental health servicesAffilia20153016882

- BojkoMJMazhnayaAMakarenkoI“Bureaucracy & beliefs”: assessing the barriers to accessing opioid substitution therapy by people who inject drugs in UkraineDrugs201522325526227087758

- LembkeAZhangNA qualitative study of treatment-seeking heroin users in contemporary ChinaAddict Sci Clin Pract20151012326538288

- Freeman-McGuireMAn Investigation into the Barriers to Treatment and Factors Leading to Treatment and Long-Term Recovery from Substance Abuse among Registered NursesSanta Barbara (CA)The Fielding Graduate University2010

- GibbsDRae OlmsteadKBrownJClinton-SherrodAMDynamics of stigma for alcohol and mental health treatment among army soldiersMilitary Psychology2011233651

- BloomAWAdvances in substance abuse prevention and treatment interventions among racial, ethnic, and sexual minority populationsAlcohol Res2016381475427159811

- SchmidtLARecent Recent developments in alcohol services research on access to careAlcohol Res2016381273327159809

- SmithLREarnshawVACopenhaverMMCunninghamCOSubstance use stigma: reliability and validity of a theory-based scale for substance-using populationsDrug Alcohol Depend2016162344326972790

- CrapanzanoKVathRJFisherDReducing stigma towards substance users through an educational intervention: harder than it looksAcad Psychiatry201438442042524619913

- DiclementeCCSchlundtDGemmellLReadiness and stages of change in addiction treatmentAm J Addict200413210311915204662

- HoersterKDMalteCAImelZEAhmadZHuntSCJakupcakMAssociation of perceived barriers with prospective use of VA mental health care among Iraq and Afghanistan veteransPsychiatr Serv201263438038222476304