?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

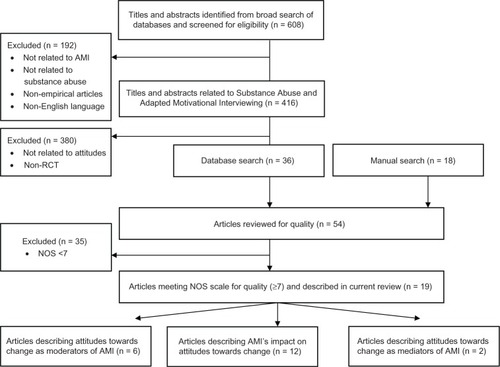

Adapted motivational interviewing (AMI) represents a category of effective, directive and client-centered psychosocial treatments for substance abuse. In AMI, patients’ attitudes towards change are considered critical elements for treatment outcome as well as therapeutic targets for alteration. Despite being a major focus in AMI, the role of attitudes towards change in AMI’s action has yet to be systematically reviewed in substance abuse research. A search of PsycINFO, PUBMED/MEDLINE, and Science Direct databases and a manual search of related article reference lists identified 416 published randomized controlled trials that evaluated AMI’s impact on the reduction of alcohol and drug use. Of those, 54 met the initial inclusion criterion by evaluating AMI’s impact on attitudes towards change and/or testing hypotheses about attitudes towards change as moderators or mediators of outcome. Finally, 19 studies met the methodological quality inclusion criterion based upon a Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale score ≥ 7. Despite the conceptual importance of attitudes towards change in AMI, the empirical support for their role in AMI is inconclusive. Future research is warranted to investigate both the contextual factors (ie, population studied) as well as deployment characteristics of AMI (ie, counselor characteristics) likely responsible for equivocal findings.

Introduction

Brief interventions are effective in reducing problematic alcohol consumption.Citation1 One brief psychosocial intervention in particular, motivational interviewing (MI), has consistently shown its usefulness in decreasing problem drinking in diverse settings.Citation2 MI is a directive, client-centered counseling style that expedites behavior change by guiding clients towards exploration and resolution of ambivalence concerning their problem behavior.Citation3 At the core of MI practice is its “spirit,” described by MI’s authors as a way of “being” with people that contrasts with common, more didactic counseling styles emphasizing information exchange, client learning of skills, and clinician-selected behavioral change objectives.Citation4 MI practitioners are encouraged to deploy a flexible repertoire of sophisticated tactics and an empathic communication style that respect client autonomy, self-efficacy, and client level of readiness.

As effective MI practice is contingent on the clinician’s ability to tactically adapt (eg, “rolling with resistance”) to the client rather than strictly adhere to a standardized intervention format,Citation5–Citation7 a “pure” form of MI is elusive. Pragmatic deployment of MI in the field and research involves a number of MI-inspired variants such as motivational enhancement therapy, brief motivational therapy, as well as other “motivational interventions” within which an MI component is embedded.Citation8,Citation9 Given the heterogeneity in MI’s application, brief interventions that adhere to the spirit of MI have been referred to as “adapted motivational interviewing” (AMI).Citation10,Citation11 Though AMI has mainly been applied to alcohol use disorders,Citation12 it has been found helpful in the treatment of other problem behaviors, such as risky drinking in drunk drivers,Citation13 poor lifestyle management in Type 2 diabetes,Citation14 asthma medication nonadherence,Citation15 criminal re-offending,Citation16 smoking,Citation17 and obesity.Citation18

Among evidence-based substance abuse treatments, AMI is distinctive by its almost exclusive focus on constituent elements of clients’ attitudes towards change. As a significant factor in the outcome from any treatment, alteration in attitudes towards change represents a key therapeutic target.Citation19 An attitude in this context can be defined as “the dynamic element in human behaviour, the motive for activity” (p 409).Citation20 This concept can be operationalized to encompass clients’ initial and dynamic appraisal of change, including positive, negative, or ambivalent reactions to change, interest, desire, and/or commitment to change, as well as acquisition of any related skill, proficiency, or belief involving self-efficacy and the consequences of change. Attitudes may interact with AMI as both a moderator and mediator of outcome, and thus constitute key proximal processes influencing how AMI works to reduce problem drinking.Citation21 A moderator is a variable that affects the direction and/or strength of the relationship between an independent variable (eg, treatment exposure) and a dependent variable (eg, problem drinking).Citation22 A mediator is a variable (eg, attitude towards change) altered by an independent variable that explains to a significant degree how an independent variable alters a dependent variable.Citation22

What are attitudes towards change?

An influential conceptualization of attitudes towards change in substance abuse is rooted in the transtheoretical model of change (TMC) and a related construct, readiness to change (RTC).Citation23 Here, stage of change and RTC are proposed as ways for clinicians to understand how clients view their problem behavior and adapt their intervention approach accordingly. TMC proposes that individuals frequently experience up to six stages towards resolution of their substance abuse problem: (1) “precontemplation,” limited recognition of the behavior posing a problem in relation to its advantages, and thus no perceived need to seek help; (2) “contemplation,” ambivalence regarding substance abuse problems, weighing of pros and cons of changing behavior, but not yet prepared to change; (3) “preparation,” initial steps towards change but without commitment to serious behavior change; (4) “action,” active efforts to reduce or eliminate drinking; (5) “maintenance,” active efforts to sustain behavioral change; and (6) “termination,” resolution of the substance abuse problem in which little concern for relapse exists.Citation24 A number of questionnaires have been developed to measure stage of change or RTC, including the Stage of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES),Citation25 the Readiness to Change Questionnaire,Citation26 the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Scale (URICA),Citation27 and the Readiness RulerCitation21 (seeCitation28 for a review). Studies indicate that movement from “precontemplation” to “contemplation” and “action” results in more positive attitudes towards changeCitation29 as well as lower alcohol consumption.Citation30

Like RTC, another attitude pertinent to AMI for substance abuse is self-efficacy.Citation31,Citation32 According to Bandura’s Social Learning Theory, self-efficacy is the belief that one can successfully execute behaviors needed to produce a desired outcome.Citation33 Self-efficacy has been shown to be a strong predictor of post-treatment drinking.Citation34 Two facets of self-efficacy, expectancy to cope successfully with difficult and stressful situations and positive outcome expectation,Citation30 have been positively associated with initiation of behavior changeCitation35 and the probability of engaging in a behavior.Citation34 Finally, other relevant attitudes towards change include attributions and perceptions of alcohol-related negative consequences, perceived drinking norms as well as personal engagement, initiation, adherence, and retention in substance abuse treatment.

Despite playing a central role in AMI, the role of attitudes towards change as either a moderator or mediator of outcome has yet to be systematically reviewed in substance abuse research. The present article describes the results of a systematic review of the AMI research literature regarding patient attitudes towards change. Specifically, the evidence in support of interactions between AMI and initial attitudes towards change in determining outcome and whether AMI positively changes these attitudes is summarized. Then, the evidence for presumptive support for AMI’s role in altering client attitudes as a mediator of AMI’s action is evaluated. A discussion of the findings’ implications for practice and future research follows. Overall, the systematic review of this literature will contribute to both a better appreciation for how AMI works to achieve its benefits as well as further development and refinement of effective theory-based therapeutics.Citation34

Procedures

Literature search

Three databases, PsycINFO, PUBMED/MEDLINE, and Science Direct, were searched using broad keywords such as “motivational interviewing + substance + attitude,” “motivational interviewing + substance,” “motivational interviewing + alcohol,” “motivational interviewing + drugs,” “motivational interviewing + attitudes to change,” “motivational interviewing + self-efficacy,” “motivational interviewing + readiness to change,” “motivational enhancement therapy + attitude+substance,” “motivational enhancement therapy + alcohol+attitude,” “motivational enhancement therapy + drugs+attitude,” “motivational enhancement therapy + attitudes to change,” “motivational enhancement therapy + readiness to change,” “motivational enhancement therapy + self-efficacy.” Electronic searching was complemented by manual reference searches of the bibliographies of relevant articles using Google Scholar. The MI bibliography provided at the official Motivational Interviewing website (www.motivationalinterviewing.org) was also searched.

Inclusion criteria

Studies selected for this review had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) claim to deploy the principles of AMI in their experimental interventions; (2) include participants with an unresolved alcohol or illicit drug use problem; (3) be published or in press in the English language; (4) include an explicit statement about participant randomization in the abstract; (5) include a non-AMI comparison group, clearly described in the abstract; and (6) include an explicit statement pertaining to attitudes towards change in the abstract.

Overview of study quality assessment

The methodological quality of the selected studies was independently assessed by two reviewers (authors SW and TS) using an approach adapted from the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS).Citation36 Compared with other assessment protocols, the NOS is appropriate for reviews that involve a large number of studies due to its brevity, flexibility, simplicity, and reliability.Citation37 The NOS scoring scale is a star rating system assessing methodology quality in three areas: participant selection (four items); comparability of exposed and nonexposed cohorts (two items); and assessment and adequacy of outcome measures (four items). Several amendments were made to the NOS to align it with the methodology and subject matter of relevant studies. Within the three areas of quality assessment, a maximum of one star can be given to each item in the selection and outcome categories, while a maximum of two stars can be given to the comparability category. An overall score is then calculated, with a maximum possible score of nine indicating the highest quality. In the absence of an explicit convention for a designation of high quality, an overall NOS score cutoff of ≥7 was chosen for inclusion in this review, a benchmark that has been used in another systematic review utilizing the NOS.Citation38 Studies were rated based on the information reported in the relevant publication only. Any between-rater discrepancies on quality ratings were reviewed and reconciled. depicts the systematic application of inclusion and exclusion criteria to obtain pertinent studies for review. details the NOS scores for each of the 54 articles meeting initial inclusion criteria. Nineteen randomized controlled trials met NOS quality criteria and were reviewed.

Figure 1 Flow chart depicting study inclusion.

Abbreviations: AMI, adapted motivational interviewing; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 1 Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) quality assessment scoring for included studies

Effect size calculations

Effect sizes were calculated for significant results for descriptive purposes in cases where the authors present t, F, or x2 statistics. Effect sizes were not calculated for mediation analyses or in cases where the authors did not provide the relevant statistics in their publication. Conventions used for effect sizes were those described by Cohen.Citation90 The conversion formulas are described as follows.Citation91,Citation92

Results

– provide details of the 19 articles retained for review. The median overall NOS score of the evaluated studies was eight (53% of studies). Six studies examined attitudes towards change as a moderator of the impact of AMI on substance abuse (), 12 studies investigated AMI’s impact on attitudes toward changing substance abuse (), and two studies examined attitudes toward change as a mediator of the impact of AMI on substance abuse (). Some individual studies appear in multiple tables.

Table 2 Included studies examining attitudes towards change as a moderator of the impact of AMI on substance abuse

Table 3 Included studies examining AMI’s impact on attitudes towards changing substance abuse

Table 4 Included studies examining attitudes towards change as a mediator of the impact of AMI on substance abuse

Of the included studies, eleven (58%) used a selected group of participants (eg, pregnant substance abusers), and eight (42%) had some discussion of the representativeness of the sample (eg, multisite recruitment). All studies recruited their experimental and comparison group participants from a common source. Eighteen (95%) studies incorporated an integrity check of the AMI intervention, which was most often a review of session audiotapes. Seventeen (89%) of the studies controlled for potentially confounding factors in data analyses, and 16 (84%) studies explicitly stated that blind assessment, treatment admission data, or biomarkers were used for outcome assessment. Fourteen (73.7%) studies reported follow-up assessments of more than 6 months following baseline assessment, while five studies (26.3%) reported a follow-up duration of less than 6 months. Overall, 15 (68.4%) studies reported a participant attrition rate of less than 20%, and two studies (10.5%) claimed no attrition.

Based on qualitative observation, compared with included studies, excluded studies had higher attrition rates, and more frequently reported a follow-up participant rate of less than 80% and follow-up durations of less than 6 months. Nonselected studies less frequently reported blinding, control for confounding factors in the analysis, and checking for therapy fidelity.

Do attitudes toward change moderate outcome from AMI?

The studies reviewed for this section and the relevant results for attitudes towards change as a moderator of AMI are summarized in . Attitudes towards change that have been investigated as moderators of AMI outcome include RTC and motivation to change, self-efficacy, personal attributions of the negative consequences of alcohol, and personal engagement in treatment. Proponents of AMI have hypothesized that as an intervention that focuses on heightening motivation for change, it is particularly well suited for individuals with less motivation to change.Citation3 Studies testing this hypothesis have yielded mixed results. In support, one studyCitation84 investigating motivation to change using the Cocaine Change Assessment Questionnaire in 165 treated cocaine-dependent patients found that low motivation to change (pre-treatment “contemplation” scores higher than “action” scores) was associated with fewer cocaine-use days with AMI compared with high motivation to change. Three other studies, however, failed to find any evidence that RTC, as measured by the Contemplation Ladder, the SOCRATES, or independent questions related to RTC, moderated AMI’s impact.Citation73,Citation78,Citation87

Two studies investigated the moderating role of self-efficacy. One studyCitation83 supported the hypothesis that individuals higher in self-efficacy have better drinking outcomes in AMI compared with individuals lower in self-efficacy. The other, in a sample of 575 injured at-risk drinkers presenting in the emergency department,Citation87 found that self-efficacy measured by independent questions did not moderate AMI’s impact on reducing substance abuse.

One study explored the moderating role of personal attributions concerning negative alcohol-related consequences. In a sample of injured at-risk drinkers presenting in the emergency department,Citation87 individuals who attributed their injury to alcohol consumption reported significantly less drinking at a 1-year follow up if they received AMI compared with individuals who also attributed their injury to alcohol but received the control condition. Lastly, with respect to counsellor assessment of participant engagement in treatment, one studyCitation82 found that homeless adolescents higher in treatment engagement had a significantly greater reduction in drug use than other homeless adolescents who were lower in treatment engagement.

Overall, based upon a review of well designed studies, moderation when detected was more likely to be in the direction predicted by proponents of AMI as opposed to the direction predicted by the TMC. Irrespective of the model used for prediction, however, the mixed findings on moderation fail to provide practical guidance in how to optimally assign patients to AMI treatments based upon initial attitudes towards change.

Does AMI alter attitudes towards change?

Studies of AMI as a way to change attitudes have evaluated its impact on RTC and motivation to change, self-efficacy, one’s perceptions concerning negative consequences of continued use, the pros and cons of use, and attitudes towards treatment. The studies reviewed in this section and their relevant results are summarized in .

Four studies investigated AMI’s role in altering RTC and motivation to change substance abuse. In a sample of 327 patients with comorbid psychosis and substance abuse,Citation79 AMI increased RTC as measured by the Readiness to Change Questionnaire significantly more than a control procedure. In a sample of 186 youth living with HIV, AMI increased RTC measured by the Readiness Ruler significantly more than a control condition at a 3-month follow-up.Citation81 Another studyCitation13 of a sample of 184 driving while impaired recidivists with substance abuse, however, detected no significant benefit with AMI compared with a control condition in increasing readiness using the Readiness to Change Questionnaire. Another studyCitation85 of homeless and substance-dependent veterans found no increase in RTC as measured by the Alcohol Readiness to Change Scale.

Two studies examined self-efficacy as an attitude that AMI aims to alter. One study of 75 homeless and substance-dependent veteransCitation85 found that compared with a control condition, AMI increased self-efficacy in dealing with situations linked to temptations to use as measured by the Situational Confidence Questionnaire at 6-month follow-up. Another studyCitation81 of youth living with HIV found no significant change in perceived self-efficacy with either AMI or a control condition.

Two studies examined whether AMI increased the perceived negative consequences of substance abuse or shifted the appraisal of the pros and cons of substance use. In a sample of patients with comorbid psychosis and substance abuse, AMI had no greater beneficial effect in altering perceptions of negative consequences of drinking as measured by the Drinker’s Inventory of Consequences than a control condition.Citation79 In cocaine-dependent patients at a 12-month follow-up, AMI was found to increase the perceived cons of cocaine use based upon the Cocaine Decisional Balance Scale significantly more compared with a control condition.Citation84

Other studies have tested AMI’s role in altering attitudes towards treatment, most notably ambivalence about change. In this context, ambivalence was operationalized using indicators such as treatment retention, seeking, adherence, and utilization. Two of nine studies supported this notion. In a sample of 448 adults presenting for substance abuse treatment, AMI was found to have a more positive effect on increasing treatment adherence compared with a control condition.Citation80 In a sample of 75 homeless and substance-dependent veterans, individuals receiving AMI were more likely to start a substance abuse treatment program at 6-month follow-up compared with individuals receiving a control condition.Citation85 AMI failed to positively alter other attitudes towards treatment in substance abuse treatment outpatients,Citation72 cocaine users,Citation77 driving while impaired recidivists,Citation13 patients in the emergency room,Citation74 pregnant substance abusers,Citation75,Citation88 and nontreatment seeking marijuana-using adolescents.Citation86

In summary, with respect to RTC, motivation to change, self-efficacy, and the perceived consequences of substance abuse, both population and context appear to play a role in whether AMI selectively alters attitude change. For example, AMI increased RTC and motivation to change in individuals with comorbid psychiatric illness and HIV but not in homeless veterans or in individuals who drink and drive. It is possible that the psychological, neuropsychological, and emotional characteristics of individuals with concurrent medical or psychiatric illness or histories of significant trauma interact with exposure to AMI to influence attitude change. Lastly, there is sparse evidence to support the contention that AMI positively alters attitudes towards treatment.

Do attitudes toward change mediate the impact of AMI?

The studies reviewed for this section and their main results are summarized in . RTC and one’s perceptions of normative drinking are two presumptive mediators that have been tested in the context of AMI and substance abuse outcomes. One studyCitation76 sought to specifically investigate RTC, measured by the Contemplation Ladder, as a mediator of AMI in hazardous drinkers presenting in emergency room settings. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions; a standard care plus assessment, standard care plus assessment combined with AMI, or AMI combined with a later booster session. At 3-month follow-up, participants receiving AMI or AMI with a booster session who were high in initial RTC exhibited fewer alcohol-related negative consequences. In a moderated mediation model, treatment resulted in fewer alcohol-related negative consequences, in part because it enhanced and maintained RTC in these individuals.

Another studyCitation78 investigated whether AMI impacts substance abuse by modifying norm perceptions. Norm perception is operationalized as an individual’s estimate of the percentage of their peers who drink more than they do, subtracted by the percentage of their peers who actually drink more based on national surveys. Using a randomized sample of 279 heavy-drinking college students, participants were assigned to one of four conditions: AMI with feedback, AMI without feedback, Web feedback only, and assessment only. The results revealed that a reduction in the discrepancy in norm perceptions mediated the effect of AMI with feedback in reducing drinking compared with the other study conditions.

In summary, the preliminary evidence indicates that, consistent with the TMC, AMI can act on RTC to positively alter substance abuse outcomes. Alteration of perceptions of normative drinking patterns also appears to be a mechanism for AMI’s action. Unfortunately, too few studies have specifically explored AMI’s presumptive mediators of outcome to make firm conclusions.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic review in the field of AMI and substance abuse that focuses specifically on patient attitudes towards change. Despite the widely accepted notion placing attitudes to change at the center of AMI’s effectiveness, surprisingly few high quality studies have specifically investigated this relationship. Pillars of AMI, such as RTC and motivation to change, have yielded mixed results as moderators of AMI’s action or as key targets for alteration. RTC may, however, play a role as a mediator of AMI on substance abuse outcomes under certain conditions, at least based upon preliminary findings. Specific conclusions regarding the importance of other attitudes to AMI’s action such as self-efficacy, the perceived negative consequences of substance use and the pros and cons of substance abuse are equivocal at best. The hypothesis that AMI plays a role in increasing positive attitudes towards treatment is largely unsupported.

Methodological factors may also underpin this incoherent picture. The marked diversity in the literature in the populations under investigation and the operationalization of key concepts are among the most likely factors contributing to discrepancies across studies. The importance of these factors in understanding the findings is deserving of further research. Moreover, quality assessment of all relevant articles and inclusion of only those studies meeting or surpassing a certain threshold, failed to neutralize discrepancies in the reporting practices seen between studies. For instance, effects sizes were impossible to derive based upon the information provided in some publications. As a result, comparative weighting of observed effects was compromised by the absence of this metric in many cases. Closer adherence to reporting conventions like the CONSORT statementCitation93 would result in more balanced and comprehensive appraisals of studies in the area and allow firmer conclusions concerning the aggregate of their findings.

Strengths and limitations

Some methodological considerations from the current review are noteworthy. Inclusion of studies with high methodological quality significantly increases the validity of the findings. Furthermore, the specific inclusion and exclusion criteria adopted for the review increased the between-study comparability. The tradeoff of this strategy meant that a small number of studies focusing on “change talk,” a putative mediator of AMI’s effect,Citation7 were excluded, given that such studies consisted primarily of secondary analyses of AMI audiotaped sessions, precluding comparisons to non-AMI conditions.

Conclusion

The role of attitudes towards change as moderators, targets of change, and mediators of AMI’s effects remains uncertain. Promising strands of evidence suggest that attitudes towards change warrant ongoing attention in research of AMI for substance abuse. Future studies should focus on increasing the reliability of findings, either by using more robust study designs or adopting better reporting practices.

Acknowledgments

Authors Wells and Smyth receive salary support from a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Team Grant (SAF 94813). The first author receives additional funding from McGill’s Department of Psychiatry Student Research Award 2012 as well as a graduate study fellowship from the Fonds de recherche en santé du Québec (FILE 23450). The authors would like to acknowledge the reviewers’ contribution in improving an earlier version of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

References

- CareyKBCareyMPMaistoSAHensonJMBrief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: a randomized controlled trialJ Consult Clin Psychol200674594395417032098

- VasilakiEIHosierSGCoxWMThe efficacy of motivational interviewing as a brief intervention for excessive drinking: a meta-analytic reviewAlcohol Alcohol200641332833516547122

- MillerWRMotivational interviewing with problem drinkersBehav Psychother198311147172

- RollnickSMillerWRWhat is motivational interviewing?Behav Cogn Psychother199523325334

- AmodeoMLundgrenLCohenABarriers to implementing evidence-based practices in addiction treatment programs: comparing staff reports on motivational interviewing, adolescent community reinforcement approach, assertive community treatment, and cognitive-behavioral therapyEval Program Plann201134438238921420171

- HettemaJSteeleJMillerWRMotivational interviewingAnnu Rev Clin Psychol200519111117716083

- MillerWRRoseGSToward a theory of motivational interviewingAm Psychol200964652753719739882

- Freyer-AdamJCoderBBaumeisterSEBrief alcohol intervention for general hospital inpatients: a randomized controlled trialDrug Alcohol Depend200893323324318054445

- FrommeKCorbinWPrevention of heavy drinking and associated negative consequences among mandated and voluntary college studentsJ Consult Clin Psychol20047261038104915612850

- BurkeBLArkowitzHMencholaMThe efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trialsJ Consult Clin Psychol200371584386114516234

- PattersonDAMotivational interviewing: does it increase clients’ retention in intensive outpatient treatment?Subst Abus2008291172319042315

- LarimerMECronceJMIdentification, prevention and treatment: a review of individual-focused strategies to reduce problematic alcohol consumption by college studentsJ Stud Alcohol Suppl20021414816312022721

- BrownTGDongierMOuimetMCBrief motivational interviewing for DWI recidivists who abuse alcohol and are not participating in DWI intervention: a randomized controlled trialAlcohol Clin Exp Res201034229230119930236

- RubakSSandbaekALauritzenTBorch-JohnsenKChristensenBGeneral practitioners trained in motivational interviewing can positively affect the attitude to behaviour change in people with type 2 diabetes. One year follow-up of an RCT, ADDITION DenmarkScand J Prim Health Care200927317217919565411

- SchmalingKBBlumeAWAfariNA randomized controlled pilot study of motivational interviewing to change attitudes about adherence to medications for asthmaJ Clin Psychol Med Settings200183167172

- McMurranMMotivational interviewing with offenders: a systematic reviewLeg Criminol Psychol20091483100

- SoriaRLegidoAEscolanoCLopez YesteAMontoyaJA randomised controlled trial of motivational interviewing for smoking cessationBr J Gen Pract20065653176877417007707

- Van DorstenBThe use of motivational interviewing in weight lossCurr Diabetes Report200775386390

- CooneyNLBaborTFDiClementeCCDel BocaFKClinical and Scientific Implications of Project MATCH222–237CambridgeCambridge University Press2003

- NorthCCSocial Problems and Social PlanningNew YorkMcGraw-Hill1932

- HeatherNSmailesDCassidyPDevelopment of a Readiness Ruler for use with alcohol brief interventionsDrug Alcohol Depend200898323524018639393

- BaronRMKennyDAThe moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerationsJ Pers Soc Psychol1986516117311823806354

- ProchaskaJDiClementeCToward a Comprehensive Model of ChangeNew York, NYPlenum Press1986

- ConnorsGJDonovanDMDiClementeCSubstance Abuse Treatment and the Stages of ChangeNew YorkGuilford Press2001

- MillerWRToniganJSAssessing drinkers’ motivation for change: the Stages of Change and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES)Psychol Addict Behav1996108189

- RollnickSHeatherNGoldRHallWDevelopment of a short ‘readiness to change’ questionnaire for use in brief, opportunistic interventions among excessive drinkersBr J Addict19928757437541591525

- McConnaughyEDiClementeCProchaskaJVelicerWStages of change in psychotherapy: a follow-up reportPsychotherapy198926494503

- CareyKPurmineDMaistoSACareyMAssessing readiness to change substance abuseClin Psychol Sci Pract19996245266

- HileMGAdkinsREThe impact of substance abusers’ readiness to change on psychological and behavioral functioningAddict Behav19982333653709668933

- RollnickSMorganMHeatherNThe development of a brief scale to measure outcome expectations of reduced consumption among excessive drinkersAddict Behav19962133773878883487

- FarisASCavellTAFishburneJWBrittonPCExamining motivational interviewing from a client agency perspectiveJ Clin Psychol200965995597019459196

- KaddenRMLittMDThe role of self-efficacy in the treatment of substance use disordersAddict Behav201136121120112621849232

- BanduraASelf-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral changePsychol Rev1977842191215847061

- DiClementeCMechanisms, determinants and processes of change in the modification of drinking behaviorAlcohol Clin Exp Res20073110 Suppl13 s20 s

- DemmelRBeckBRichterDRekerTReadiness to change in a clinical sample of problem drinkers: relation to alcohol use, self-efficacy, and treatment outcomeEur Addict Res200410313313815258444

- StangACritical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysesEur J Epidemiol201025960360520652370

- HootmanJMDribanJBSitlerMRHarrisKPCattanoNMReliability and validity of three quality rating instruments for systematic reviews of observational studiesRes Synth Methods20112110118

- Leonardi-BeeJPritchardDBrittonJAsthma and current intestinal parasite infection: systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Respir Crit Care Med2006174551452316778161

- CarrollKMLibbyBSheehanJHylandNMotivational interviewing to enhance treatment initiation in substance abusers: an effectiveness studyAm J Addict200110433533911783748

- AlemagnoSAStephensRCStephensPShaffer-KingPWhitePBrief motivational intervention to reduce HIV risk and to increase HIV testing among offenders under community supervisionJ Correct Health Care200915321022119477803

- BakerALewinTReichlerHMotivational interviewing among psychiatric in-patients with substance use disordersActa Psychiatr Scand2002106323324012197863

- DenchSBennettGThe impact of brief motivational intervention at the start of an outpatient day programme for alcohol dependenceBehav Cogn Psychother20002802121130

- LongshoreDGrillsCAnnonKEffects of a culturally congruent intervention on cognitive factors related to drug-use recoverySubst Use Misuse19993491223124110419221

- McKeeSACarrollKMSinhaREnhancing brief cognitive-behavioral therapy with motivational enhancement techniques in cocaine usersDrug Alcohol Depend20079119710117573205

- SwansonAJPantalonMVCohenKRMotivational interviewing and treatment adherence among psychiatric and dually diagnosed patientsJ Nerv Ment Dis19991871063063510535657

- D’AmicoEJMilesJNSternSAMeredithLSBrief motivational interviewing for teens at risk of substance use consequences: a randomized pilot study in a primary care clinicJ Subst Abuse Treat2008351536118037603

- DavisTMBaerJSSaxonAJKivlahanDRBrief motivational feedback improves post-incarceration treatment contact among veterans with substance use disordersDrug Alcohol Depend200369219720312609701

- CareyKBHensonJMCareyMPMaistoSAWhich heavy drinking college students benefit from a brief motivational intervention?J Consult Clin Psychol200775466366917663621

- LaChanceHFeldstein EwingSWBryanADHutchisonKEWhat makes group MET work? A randomized controlled trial of college student drinkers in mandated alcohol diversionPsychol Addict Behav200923459861220025366

- OtiashviliDKirtadzeIO’GradyKEJonesHEDrug use and HIV risk outcomes in opioid-injecting men in the Republic of Georgia: behavioral treatment+naltrexone compared to usual careDrug Alcohol Depend20121201–3142121742445

- SaundersBWilkinsonCPhillipsMThe impact of a brief motivational intervention with opiate users attending a methadone programmeAddiction19959034154247735025

- BellackASBennettMEGearonJSBrownCHYangYA randomized clinical trial of a new behavioral treatment for drug abuse in people with severe and persistent mental illnessArch Gen Psychiatry200663442643216585472

- BoothRECorsiKFMikulich-GilbertsonSKFactors associated with methadone maintenance treatment retention among street-recruited injection drug usersDrug Alcohol Depend200474217718515099661

- BorsariBCareyKBEffects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkersJ Consult Clin Psychol200068472873310965648

- BrownTGDongierMOuimetMCThe role of demographic characteristics and readiness to change in 12-month outcome from two distinct brief interventions for impaired driversJ Subst Abuse Treat201242438339122119179

- CareyKBHensonJMCareyMPMaistoSAPerceived norms mediate effects of a brief motivational intervention for sanctioned college drinkersClin Psychol (New York)2010171587122238504

- CarrollKMBallSANichCMotivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: a multisite effectiveness studyDrug Alcohol Depend200681330131216169159

- CarrollKMMartinoSBallSAA multisite randomized effectiveness trial of motivational enhancement therapy for Spanish-speaking substance usersJ Consult Clin Psychol200977599399919803579

- GotiJDiazRSerranoLBrief intervention in substance-use among adolescent psychiatric patients: a randomized controlled trialEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry201019650351119779855

- IngersollKSFarrell-CarnahanLCohen-FilipicJA pilot randomized clinical trial of two medication adherence and drug use interventions for HIV+ crack cocaine usersDrug Alcohol Depend20111161–317718721306837

- KidorfMDisneyEKingVKolodnerKBeilensonPBroonerRKChallenges in motivating treatment enrollment in community syringe exchange participantsJ Urban Health200582345646716014875

- MaistoSAConigliaroJMcNeilMKraemerKConigliaroRLKelleyMEEffects of two types of brief intervention and readiness to change on alcohol use in hazardous drinkersJ Stud Alcohol200162560561411702799

- MasonMPatePDrapkinMSozinhoKMotivational interviewing integrated with social network counseling for female adolescents: a randomized pilot study in urban primary careJ Subst Abuse Treat201141214815521489741

- McCambridgeJStrangJThe efficacy of single-session motivational interviewing in reducing drug consumption and perceptions of drug-related risk and harm among young people: results from a multi-site cluster randomized trialAddiction2004991395214678061

- MontgomeryLBurlewAKKosinskiASForcehimesAAMotivational enhancement therapy for African American substance users: a randomized clinical trialCultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol201117435736521988576

- OndersmaSJWinhusenTEricksonSJStineSMWangYMotivation enhancement therapy with pregnant substance-abusing women: does baseline motivation moderate efficacy?Drug Alcohol Depend20091011–2747919101099

- OrfordJHodgsonRCopelloAWiltonSSleggGTo what factors do clients attribute change? Content analysis of follow-up interviews with clients of the UK Alcohol Treatment TrialJ Subst Abuse Treat2009361495818547778

- OstermanRLDyehouseJEffects of a motivational interviewing intervention to decrease prenatal alcohol useWest J Nurs Res201234443445421540353

- RoblesRRReyesJCColonHMEffects of combined counseling and case management to reduce HIV risk behaviors among Hispanic drug injectors in Puerto Rico: a randomized controlled studyJ Subst Abuse Treat200427214515215450647

- SteinLAMontiPMColbySMEnhancing substance abuse treatment engagement in incarcerated adolescentsPsychol Serv200631253420617117

- StottsALSchmitzJMRhoadesHMGrabowskiJMotivational interviewing with cocaine-dependent patients: a pilot studyJ Consult Clin Psychol200169585886211680565

- BallSAMartinoSNichCSite matters: multisite randomized trial of motivational enhancement therapy in community drug abuse clinicsJ Consult Clin Psychol200775455656717663610

- MastroleoNRMurphyJGColbySMMontiPMBarnettNPIncident-specific and individual-level moderators of brief intervention effects with mandated college studentsPsychol Addict Behav201125461662421766975

- MontiPMBarnettNPColbySMMotivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinkingAddiction200710281234124317565560

- MullinsSMSuarezMOndersmaSJPageMCThe impact of motivational interviewing on substance abuse treatment retention: a randomized control trial of women involved with child welfareJ Subst Abuse Treat2004271515815223094

- SteinLAMinughPALongabaughRReadiness to change as a mediator of the effect of a brief motivational intervention on posttreatment alcohol-related consequences of injured emergency department hazardous drinkersPsychol Addict Behav200923218519519586135

- SteinMDHermanDSAndersonBJA motivational intervention trial to reduce cocaine useJ Subst Abuse Treat200936111812518657938

- WaltersSTVaderAMHarrisTRFieldCAJourilesENDismantling motivational interviewing and feedback for college drinkers: a randomized clinical trialJ Consult Clin Psychol2009771647319170454

- BarrowcloughCHaddockGWykesTIntegrated motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy for people with psychosis and comorbid substance misuse: randomised controlled trialBMJ2010341c632521106618

- DennisMScottCKFunkRAn experimental evaluation of recovery management checkups (RMC) for people with chronic substance use disordersEval Program Plann2003263339352

- Naar-KingSParsonsJTMurphyDKolmodinKHarrisDRA multisite randomized trial of a motivational intervention targeting multiple risks in youth living with HIV: initial effects on motivation, self-efficacy, and depressionJ Adolesc Health201046542242820413077

- PetersonPLBaerJSWellsEAGinzlerJAGarrettSBShort-term effects of a brief motivational intervention to reduce alcohol and drug risk among homeless adolescentsPsychol Addict Behav200620325426416938063

- Project MATCH Research GroupMatching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomesAlcohol Clin Exp Res1998226130013119756046

- RohsenowDJMontiPMMartinRAMotivational enhancement and coping skills training for cocaine abusers: effects on substance use outcomesAddiction200499786287415200582

- WainRMWilbournePLHarrisKWMotivational interview improves treatment entry in homeless veteransDrug Alcohol Depend20111151–211311921145181

- WalkerDDStephensRRoffmanRRandomized controlled trial of motivational enhancement therapy with nontreatment-seeking adolescent cannabis users: a further test of the teen marijuana check-upPsychol Addict Behav201125347448421688877

- WaltonMAGoldsteinALChermackSTBrief alcohol intervention in the emergency department: moderators of effectivenessJ Stud Alcohol Drugs200869455056018612571

- WinhusenTKroppFBabcockDMotivational enhancement therapy to improve treatment utilization and outcome in pregnant substance usersJ Subst Abuse Treat200835216117318083322

- Project MATCH Research GroupMatching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomesJ Stud Alcohol1996581729

- CohenJJStatistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences2nd edNew JerseyErlbaum1988

- FriedmanHSimplified determinations of statistical power, magnitude of effect and research sample sizesEduc Psychol Meas198242521526

- WolfFMMeta Analysis: quantitative methods for research synthesisBeverly Hills, CASage1986

- SchulzKFAltmanDGMoherDGroupCCONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trialsBMJ2010340c33220332509