Abstract

Introduction

Historically, racial and ethnic minority populations have been underrepresented in clinical research, and the recruitment and retention of women and ethnic minorities in clinical trials has been a significant challenge for investigators. The National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN) conducts clinical trials in real-life settings and regularly monitors a number of variables critical to clinical trial implementation, including the retention and demographics of participants.

Purpose

The examination of gender, race/ethnicity, and age group differences with respect to retention characteristics in CTN trials.

Methods

Reports for 24 completed trials that recruited over 11,000 participants were reviewed, and associations of gender, race/ethnicity, and age group characteristics were examined along with the rate of treatment exposure, the proportion of follow-up assessments obtained, and the availability of primary outcome measure(s).

Results

Analysis of the CTN data did not indicate statistical differences in retention across gender or race/ethnicity groups; however, retention rates increased for older participants.

Conclusion

These results are based on a large sample of patients with substance use disorders recruited from a treatment-seeking population. The findings demonstrate that younger participants are less likely than older adults to be retained in clinical trials.

Introduction

Historically, women as well as racial and ethnic minority populations have been under-represented in clinical research, despite national recommendationsCitation1 and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) policies.Citation2–Citation5 Much has been written about difficulties recruiting women and minorities into clinical trials. However, the recruitment and retention of such participants is fundamental for the validity and potential generalizability of study results, which in turn depend upon the provision of appropriate treatment doses and the collection of required outcome measures over the course of the study.Citation6,Citation7 Adequate participation of women, racial/ethnic minorities, and the full range of age groups in all aspects of clinical research is also critical for appropriate subgroup analyses. This is especially important because data suggest a greater vulnerability of women and minorities to the adverse medical and social consequences of substance use disorders, such as higher rates of human immunodeficiency virus infection associated with drug use and higher rates of involvement in the criminal justice system.Citation4,Citation8–Citation11 Such vulnerability underscores the need to successfully retain all participants in substance use research and maintain sample sizes sufficient to draw reasonable conclusions and increase the applicability of results for real-life treatment programs.Citation4,Citation12

Although minority groups are generally thought to have lower retention rates in research studies in comparison with non-Hispanic white groups, results have been mixed in previous studies examining retention rates in substance use disorder research. Two recent publications addressing substance use disorder researchCitation11,Citation13 reported lower retention rates for African Americans compared with whites. Magruder et alCitation13 found that younger adult African Americans had the lowest retention rates. However, Bisaga et alCitation14,Citation15 did not find demographic differences in retention in the two cocaine studies they reported. Similar observations have been made regarding differential retention rates by gender.Citation4,Citation5

The National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN) was established by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and recently celebrated 10 years of conducting multisite clinical trials comparing the effectiveness of interventions for substance use disorders.Citation16,Citation17 The CTN has been instrumental in facilitating, developing, and implementing evidence-based treatments in community treatment programs around the USA.Citation18,Citation19 The CTN recruits participants from among individuals seeking treatment for substance use disorders at community-based treatment programs. It has enrolled a diverse population of individuals that includes racial/ethnic minorities, adolescents, pregnant women, and persons with co-occurring disorders.Citation17

A large sample (11,449 randomized participants) from 24 completed clinical trials in the CTN were examined to detect any differences in three retention indicators (availability of primary outcome measure[s], treatment exposure, and attendance at follow-up visits) based on demographic characteristics (age, gender, and racial or ethnic background). This paper reports overall retention rates in these studies across those demographic characteristics, and compares them with analogous rates in the published literature. The current paper extends the literature by looking across trials with a diverse set of data and by using three different (though related) measures that reflect retention in clinical trials, whereas prior studies have typically relied on only one study and one indicator of retention.

Methods

Data source

Data from the first 24 CTN completed multisite clinical trials (listed in ) were analyzed. The data examined were completely de-identified to prevent linkages to individual research participants. This included removal of all personal health information and indirect identifiers that are not listed as personal health information but could lead to “deductive disclosure,” such as comment fields and site numbers. The numbering sequence is incomplete, not because some clinical trials were excluded, but because some of the studies were surveys or other types of CTN research projects. The 24 trials comprised six medication trials (with or without combined psychosocial treatment) using buprenorphine/naloxone, two medication trials combining methylphenidate with psychosocial treatment, one medication trial combining nicotine patch and psychosocial treatment, and 15 psychosocial trials. Results from these studies are published elsewhere.Citation17 A total of 11,449 individuals were recruited into the studies, across 120 Community Treatment Programs (CTPs). All studies were approved by local institutional review boards, and all participants signed written informed consent prior to participating in the research. Further details on each trial can be found at www.ctndatashare.org and www.ctndisseminationlibrary.org.

Table 1 CTN studiesTable Footnotea

Study variables

Participants’ retention in a trial was quantified using three measures as described in Wakim et al.Citation20

Availability of the primary outcome measure(s): The primary outcome measure was the dependent variable used in the initial primary analysis for each trial. It was extracted directly from a case report form used to record data or calculated from several case report form fields. In some studies, the primary outcome was a set of repeated measures, for example, drug use each week over 8 weeks. “Availability of the primary outcome measure(s)” was expressed as a percentage: the number of measures actually assessed (nonmissing) divided by the number of measures that were expected to be assessed, and multiplied by 100, from all participants, regardless of whether they dropped out of the treatment or were lost to follow-up.

Treatment exposure: This measure focused on the treatment that each participant (in the control or experimental arm) actually received, compared with the treatment each participant was intended to receive. If the treatment was medication (or placebo), it reflected the actual compliance of taking the medicine. For psychosocial treatments, it reflected attendance at treatment sessions (either the active psychosocial therapy sessions or whatever comparison sessions were in place for the trial). “Treatment exposure” was expressed as a percentage: the number of medication or placebo doses taken or psychosocial therapy sessions attended, divided by the corresponding number that a participant was expected to take or attend, and multiplied by 100. For trials that combined medication and psychosocial treatment, the definition of treatment exposure depended on the focus of the trial. For example, in two trials, treatment exposure was based on medication compliance; in another, however, treatment exposure was based on weekly visit attendance.

Attendance at follow-up visit(s): Each trial entailed one or more follow-up visits. “Attendance at follow-up visit(s)” was expressed as a percentage: the number of follow-up visits actually attended, divided by the number of follow-up visits that a participant was expected to attend, and multiplied by 100.

These retention measures were analyzed with respect to three demographic groups: gender (female, male, missing), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic African American, non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska native, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic other, multirace, missing/choose not to answer), and age group (<18 years, 18 to <25, 25 to <35, 35 to <45, 45 to <55, 55 to <65, 65 to <75, 75+, missing). Demographic categories with very low representation were excluded.

Data analysis

For each trial, a statistical model at the participant level was fit for each of the three participation measures as the dependent variable. Generalized estimating equation models were used, which are recommended for the analysis of data comprising repeated discrete observations of an outcome and a set of covariates.Citation21 The authors started by including the three main factors (gender, race/ethnicity, and age group), all two-way interactions, and their three-way interaction. In cases where the dependent variable at the participant level was 0 or 1 (ie, session attended or not, pill taken or not), logistic regression models were fitted. In cases where the dependent variable at the participant level was a count (eg, number of pills taken), Poisson regression models were fitted. In most trials, there were repeated measures within participant. In such cases, repeated measures models were fitted, assuming an autoregressive correlation structure.

If the three-way interaction was not statistically significant at the 0.01 level, it was dropped from the model, which was fitted again with the main effects and all two-way interactions. Any two-way interaction that was not statistically significant at the 0.01 level was subsequently dropped from the model, which was fitted again. The final model included the three main effects, whether statistically significant or not, and the two-way and three-way interactions that were statistically significant.

When only one demographic subgroup was represented in a trial, the whole demographic grouping was excluded from the model for that trial. For example, in one trial (CTN0010-BUP Adolescents), the age group factor was excluded from the three statistical models because all participants were less than 25 years old. Similarly, race/ethnicity was excluded from the statistical models for another trial (CTN0021-Spanish MET) because all participants were Hispanic, and gender was excluded from the models in some gender trials, for example, CTN0013-MET for pregnant women.

Each generalized estimating equation model produced least-squares means for each level of gender, race/ethnicity, and age group. For each of the three participation measures, the least-squares means were then combined across trials, after controlling for a trial effect (each trial with a 0–1 code), to produce the final estimates of participation for each of the gender, race/ethnicity, and age group.

Instead of calculating simple averages for each demographic group directly from the raw data, this modeling approach was used to account for any imbalances in representation. For example, the proportion of young participants among women may have been considerably higher by chance than that among men. If so, simple averages for each gender group may confound the gender and age group effects. So to separate the two effects, one needs to model participation with both factors in the model. The fact that many trials incorporated repeated measures also required some special modeling.

Results

Selected characteristics of clinical trials

summarizes the clinical trials analyzed and shows that the sample sizes in the 24 trials ranged from 113 to 1281. The participant demographic characteristics are shown in . Demographics show that 41% of individuals were female. Eight participants with missing gender information were excluded from this analysis.

Table 2 Demographic characteristics

As shown in , 53% of participants were non-Hispanic white, 21% were non-Hispanic African American, and 17% were Hispanic. The exhaustive, mutually exclusive categorization was based on participants’ answers to one question on race and one on ethnicity. Because the number of participants was low for the categories “Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska native,” “Non-Hispanic Asian,” “Non-Hispanic Pacific Islander,” “Non-Hispanic other,” and “Missing/Choose not to answer,” these were excluded from the analysis.

In terms of age group composition, the majority of individuals were between 25 and 54 years old (75%), with an average age of 36 years. Categories “65 to <75,” “75+” and “Missing” were excluded from the analysis because of their low count. Also excluded was the category “<18” because 98% of participants (n = 711) from this age group came from only two studies (CTN0014-BSFT and CTN0028-ADHD Adolescents) that focused on adolescents. Including this category would have confounded the effects of the age group with those two studies. For example, if the group of participants <18 years old reflected low retention rates, it could not be known whether this was the effect of the age category or perhaps the high participant burden in those two studies.

Results of retention-related measures

As a result of excluding the above demographic categories, 11,122 of the 11,449 participants were included in the final analyses.

None of the individual trial statistical models comprised two-way or three-way interactions that were statistically significant at the 0.01 level and, therefore, all final models included only the three main effects, with a few exceptions for trials where one of the main effects (demographic group) was also excluded for reasons previously stated. Three tables (one for each retention measure) showing the results of the individual trial analyses, are provided as Appendices , , and .

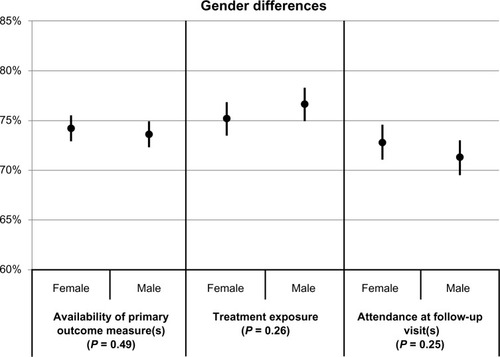

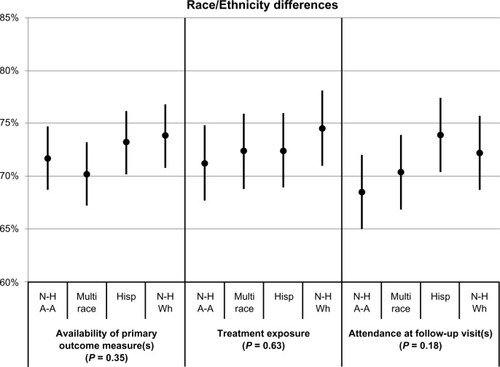

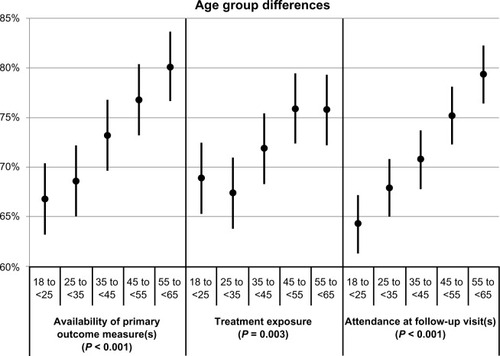

Differences in participation between gender, race/ethnicity, and age groups after combining results across trials are shown in and –, respectively. provides the values of the point estimates plotted in the three figures, as well as the values of the three measures for all demographic groups and all trials combined (bottom row). – also show 95% confidence intervals around the point estimates.

Figure 1 Associations of gender with the availability of primary outcome measure(s), treatment exposure, and attendance at follow-up visits.a

Figure 2 Associations of race/ethnicity with the availability of primary outcome measure(s), treatment exposure, and attendance at follow-up visits.a

Abbreviations: N-H A-A, non-Hispanic African American; Hisp, Hispanic; N-H Wh, non-Hispanic white.

Figure 3 Associations of age group with the availability of primary outcome measures, treatment exposure, and attendance at follow-up visits.a

Table 3 Measures of participation based on 24 clinical trials (in %)

P-values resulting from the comparison between the demographic groups are also provided. shows that gender differences were not statistically significant on any of the three participation measures (P values ≥0.25). The point estimates ranged between 71% and 77%. shows that race/ethnicity differences were also not statistically significant on any of the three participation measures (P values ≥0.18). The point estimates ranged between 69% and 75%. In contrast, shows that age group differences were statistically significant (P values ≤0.003); in fact, it shows that participation increases with age. Point estimates were around 67% for the youngest participants and around 78% for the oldest participants.

The three participation measures are correlated. For example, participants who attended the follow-up visits are more likely to have come for their psychosocial therapy and to have completed the primary outcome assessments.

Discussion

This paper discusses the relationships between demographic characteristics and ongoing research participation rates of treatment seeking individuals in 24 clinical trials completed in the CTN. Three separate measures of ongoing study participation and retention (availability of primary outcome, treatment exposure, and attendance to follow-up visits) were examined. For each trial, results pertaining to these three retention measures were presented in Wakim et al.Citation20 In the overall sample, fairly high participation rates were found with participation ranging from approximately 70% to 80%. Statistically significant differences were not found among gender or racial/ethnic groups, but differences were found among age groups. These findings have important and broad implications for research design and planning because three separate indicators of study participation and retention were examined across a large sample in 24 multisite clinical trials, rather than only a single indicator in one or two small trials.

Since its inception, the CTN has implemented several strategies to enhance participant recruitment and retention. These include:

Site selection: Study teams examine the demographic characteristics of the population served by the CTPs to ensure that women and racial/ethnic minorities are represented adequately.

Training: Staff are trained at the beginning of each study and participate in weekly conference calls to discuss progress and identify areas for improvement. In addition, NIDA sponsors national trainings and regular web-based training on recruitment and retention issues to improve skills that promote specific successful strategies. These training sessions also provide a forum to exchange lessons learned.

Monitoring: Study leaders have access to these data on a daily basis. They closely monitor recruitment and retention rates as the trial is implemented as well as conduct weekly calls with staff at each participating site to discuss problems and recommend solutions. These strategies seem to be working well, since the CTN clinical trials examined here have been able to recruit and retain a diverse group of individuals.

Recruitment

The recruitment of women, adolescents, and racial/ethnic minorities depends largely on the particular population that attends the clinic as well as the clinic’s specialty (eg, programs targeted to women or adolescents). The CTN recruitment rates (41% female, 53% non-Hispanic white, 21% non-Hispanic African American, and 17% Hispanic) mirror national figures on substance use disorder treatment reported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration,Citation22,Citation23 suggesting that, at least for these demographic groups, the CTN trials have recruited a sample that is representative of the treatment-seeking US population and that CTN findings could be generalizable.

However, the CTN appears to be less successful in recruiting a representative number of American Indian/Alaska Natives (1.1 %) or Asian Americans (0.4%) into the trials, with numbers that are lower than the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s estimate.Citation22,Citation23 Of those persons admitted into treatment, 2.3% are American Indian/Alaska Natives and 1% are Asian Americans. Research is needed to uncover the reasons for these low enrollment rates in the CTN; however, the authors speculate that one reason could be that few CTPs in the CTN actually serve these groups, due to demographic, geographic, or other factors. The CTN is exploring the possibility of including additional specific treatment programs that serve these populations.

Retention-related measures

As described by Wakim et al,Citation20 the retention measures in CTN trials ranged from 45% to 100%, with an average of 73% across all studies (). This range of participation could reflect a combination of variables, such as type of treatment, protocol characteristics or design, treatment program characteristics, and participant characteristics. This range also reflects those reported previously for substance use disorders research (38% reported by Heinzerling et alCitation24 to 92% reported by Fals-Stewart and LamCitation25).

Gender

Analysis of the overall CTN data did not indicate significant differences in trial retention across gender, confirming the observation of Greenfield et al,Citation4 who conducted a review of the literature and concluded that gender is not a significant factor in treatment retention.

Race/Ethnicity

A statistically significant difference was observed for some of the retention indicators in some of the trials, showing that non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics remain in certain studies longer than non-Hispanic African Americans (see Appendices –). This finding is congruent with the published literature. However, when all 24 trials were combined, significant differences were not found among racial/ethnic groups, suggesting that the directionality of the differences was not consistent enough to yield statistically significant findings overall. Potential reasons for this observation include: (1) the analysis encompassed a wide range of intervention types (psychosocial, medication, combined treatment) and target drugs used (opiates, stimulants, poly-drug use disorders); and (2) the analysis reflected studies conducted across a broad range of programs and treatment settings with highly variable characteristics (eg, treatment modality philosophy, size and staff characteristics, client case mix, geographic area).

Age groups

The ages of the participants enrolled were also examined; statistically significant differences between older and younger populations across the overall sample were found, showing that retention was higher for older participants. These differences were not observed in every trial, however. This is consistent with reports by Magruder et al,Citation13 who analyzed a subset of these trials and found that younger participants were least likely to be retained. This is also consistent with Warden et al,Citation26 who analyzed data from a large depression study and found that, regardless of income, younger enrollees had a greater likelihood of attrition. Warden et al speculate that there could be a relationship between older age and a perceived need for treatment, better judgments in life, or a more prolonged history of illness.

The wide range of factors in these analyses, including study characteristics (eg, type and length of study), treatment program characteristics (eg, methadone programs, women only), and primary drug of abuse (eg, opiates, stimulants, alcohol), makes it difficult to speculate as to why older participants have a higher retention rate. Nevertheless, older participants may have stronger motivations to enter and complete treatment, since they may have moved through the stages of change and have experienced too many negative consequences related to their addiction, consistent with Fiorentine and Hillhouse’sCitation27 model of recovery. Additionally, some longitudinal studies in alcohol have shown a decline in consumption over time.Citation28 In clinical settings, providers may associate older age with better treatment outcomes. One study physician noted that this might be because it becomes harder to live the life of an addict as one gets older.Citation29 Also, older addicts do not seem to experience the same pleasurable effects of the drugs as they did at a younger age, perhaps due to drug tolerance or other physiological factors. Furthermore, the devastating effects of drug use and abuse on people’s lives accumulate over time.

Limitations

This is an observational analysis. Other factors not considered may affect clinical trial participation or may be confounded with demographics. For example, different racial/ethnic groups may have different preferences for a primary drug of abuse or different patterns of drug use. By controlling for a trial effect in the model used here, to some extent the primary drug of abuse was controlled for, but only for trials focused on one specific drug of abuse. However, if a trial includes participants reporting a wide range of primary drugs of abuse, and if certain age or racial/ethnic groups tend to use certain drugs, then the effects of age or race/ethnicity and primary drug of abuse are confounded.

Variations across trials in the specific definition of the retention indicators utilized in this paper (ie, availability of primary outcome measure[s], treatment exposure, and attendance at follow-up visit[s]) may also contribute to potential confounding. In addition, unmeasured factors such as the quality of treatment in each trial may have affected retention. However, trial differences were captured and controlled for, to some extent, in the statistical model that combined the least-squares means.

Conclusion

The significant attention that CTN investigators have focused on recruitment and retention efforts appears to have paid off in better demographic representativeness of study samples of whites, African Americans, and Hispanics. However, the authors’ analyses strongly suggest that future investigators in addiction treatment clinical trials increase their efforts to recruit and retain certain specific populations: (1) American Indian/Alaska Natives and Asian American populations, since they seem to underparticipate in clinical trial research; (2) younger individuals, since they are the population with the lowest retention rates; and (3) non-Hispanic African Americans, since their retention rates may be lower than other racial/ethnic groups. Strategies for increased recruitment and retention may include greater care to address sociocultural differences relating to both drug use and medical research, as well as multipronged strategies to track and retain participants. Another strategy to strengthen participation of minority subgroups in addiction (and other biomedical) research may be to increase the representation of minority investigators in the biomedical research workforce. Recent studies have highlighted such underrepresentation.Citation30,Citation31

To summarize, the participation and ongoing retention rates of 70%–80% did not differ by race/ethnicity or gender. However, participation and retention rates increased significantly with age. These results highlight the need to investigate the reason(s) why younger adult rates of participation are lower. Lastly, the results of any study should be interpreted with caution when the recruitment and retention rates of eligible participants are low.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the data management and statisticians at the Duke Clinical Research Institute for their contributions to the NIDA Clinical Trials Network.

Disclosure

CL Rosa, PG Wakim, and HI Perl are employees of the Center for the Clinical Trials Network of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH, the funding agency for the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network. The opinions in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the NIH or the US government. The authors declare no further conflicts of interest in relation to this paper.

References

- KohHKOppenheimerSCMassin-ShortSBEmmonsKMGellerACViswanathKTranslating research evidence into practice to reduce health disparities: a social determinants approachAm J Public Health2010100Suppl 1S72S8020147686

- National Institutes of Health (NIH)Amendment: NIH Policy and Guidelines on the Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research – October 2001Bethseda MDNIH1092001 Available from: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-02-001.htmlAccessed August 4, 2010

- DurantRWDavisRBSt GeorgeDMWilliamsICBlumenthalCCorbie-SmithGMParticipation in research studies: factors associated with failing to meet minority recruitment goalsAnn Epidemiol200717863464217531504

- GreenfieldSFBrooksAJGordonSMSubstance abuse treatment entry, retention and outcome in women: A review of the literatureDrug Alcohol Depend200786112116759822

- SullivanPSMcNaghtenDBegleyEHutchinsonACargillVAEnrollment of racial/ethnic minorities and women with HIV in clinical research studies of HIV medicinesJ Natl Med Assoc200799324225017393948

- RobinsonKADennisonCRWaymanDMPronovostPJNeedhamDMSystematic review identifies number of strategies important for retaining study participantsJ Clin Epidemiol20076075776417606170

- FabricatoreANWaddenTAMooreRHAttrition from randomized controlled trials of pharmacological weight loss agents: a systematic review and analysisObes Rev200910333334119389060

- BurlewAKFeasterDBrechtMHubbardRMeasurement and data analysis in research addressing health disparities in substance abuseJ Subst Abuse Treat2009361254318550320

- AlvarezRAVasquezEMayorgaCCFeasterDJMitraniVBIncreasing minority research participation through community organization outreachWest J Nurs Res200628554156016829637

- CarrollKMMartinoSBallSAA multisite randomized effectiveness trial of motivational enhancement therapy for Spanish-speaking substance usersJ Consult Clin Psychol200977599399919803579

- MilliganCONichCCarrollKMEthnic differences in substance abuse treatment retention, compliance and outcome from two clinical trialsPsychiatr Serv200455216717314762242

- YanceyAKOrtegaANKumanyikaSKEffective recruitment and retention of minority research participantsAnnu Rev Public Health20062712816533107

- MagruderKMOuyangBMillerSTilleyBRetention of under-represented minorities in drug abuse treatment studiesClin Trials20096325226019528134

- BisagaAAharonoivhEGarawiFA randomized placebo-controlled trial of gabapentin for cocaine dependenceDrug Alcohol Depend200681326727416169160

- BisagaAAharonoivhEChengWYA placebo-controlled trial of memantine for cocaine dependence with high-value voucher incentives during a pre-randomization lead-in periodDrug Alcohol Depend20101119710420537812

- TaiBStrausMMLiuDSparenborgSJacksonRMcCartyDThe first decade of the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network: Bridging the gap between research and practice to improve drug abuse treatmentJ Subst Abuse Treat201038S4S1320307794

- WellsEASaxonAJCalsynDAJacksonTRDonovanDStudy results from the Clinical Trials Network’s first 10 years: Where do they lead?J Subst Abuse Treat2010381S14S3020307792

- MartinoSBrighamGSHigginsCPartnerships and pathways of dissemination: The National Institute on Drug Abuse – Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Blending Initiative in the Clinical Trials NetworkJ Subst Abuse Treat2010381S31S4320307793

- RomanPMAbrahamAJRothrauffTCKnudsenHKA longitudinal study of organizational formation, innovation of adoption, and dissemination activities within the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials NetworkJ Subst Abuse Treat2010381S44S5220307795

- WakimPRosaCKothariPMichelMERelation of study design to recruitment and retention in CTN trialsAm J Drug Alcohol Abuse201137542643321854286

- ZegerSLLiangKYLongitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomesBiometrics1986421211303719049

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)Highlights for 2007 treatment episode data set (TEDS)Rockville, MDSAMHSA2009 [last updated February 17, 2009]. Available from: http://oas.samhsa.gov/TEDS2k7highlights/TEDSHighl2k7Tbl2a.htmAccessed July 6, 2010

- Division of Population Surveys, Office of Applied Studies, SAMHSA, RTI InternationalResults from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: national findingsRockville, MDSAMHSA2008 [last updated September 4, 2008]. Available from: http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k7NSDUH/2k7results.cfm#7.3Accessed July 6, 2010

- HeinzerlingKGSwansonAKimSRandomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for the treatment of methamphetamine dependenceDrug Alcohol Depend2010109202920092966

- Fals-StewartWLamWKKComputer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trialExp Clin Psychopharmacol2010181879820158298

- WardenDRushAJWisniewskiSRIncome and attrition in the treatment of depression: a STAR*D reportDepress Anxiety200926762263319582825

- FiorentineRHillhouseMPReplicating the Addicted-Self Model of recoveryAddict Behav20032861063108012834651

- MoosRHSchutteKBrennanPMoosBSTen-year patterns of alcohol consumption and drinking problems among older women and menAddiction200499782983815200578

- Pers commBlaineJack9142010

- GintherDKSchafferWTSchnellJRace, ethnicity, and NIH research awardsScience201133360451015101921852498

- TabakLACollinsFSWeaving a richer tapestry in biomedical scienceScience8192011333604594094121852476

Appendices

Appendix 1 Statistical significance (P-values) of parameters in models for availability of primary outcome measure

Appendix 2 Statistical significance (P-vales) of parameters in models for treatment exposure

Appendix 3 Statistical significance (P-values) of parameters in models for attendance at follow-up visits