Abstract

Depression, type 2 diabetes (T2D), and metabolic syndrome (MetS) are often comorbid. Depression per se increases the risk for T2D by 60%. This risk is not accounted for by the use of antidepressant therapy. Stress causes hyperactivation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, by triggering the hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) secretion, which stimulates the anterior pituitary to release the adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH), which causes the adrenal secretion of cortisol. Depression is associated with an increased level of cortisol, and CRH and ACTH at inappropriately “normal” levels, that is too high compared to their expected lower levels due to cortisol negative feedback. T2D and MetS are also associated with hypercortisolism. High levels of cortisol can impair mood as well as cause hyperglycemia and insulin resistance and other traits typical of T2D and MetS. We hypothesize that HPA axis hyperactivation may be due to variants in the genes of the CRH receptors (CRHR1, CRHR2), corticotropin receptors (or melanocortin receptors, MC1R-MC5R), glucocorticoid receptor (NR3C1), mineralocorticoid receptor (NR3C2), and of the FK506 binding protein 51 (FKBP5), and that these variants may be partially responsible for the clinical association of depression, T2D and MetS. In this review, we will focus on the correlation of stress, HPA axis hyperactivation, and the possible genetic role of the CRHR1, CRHR2, MCR1–5, NR3C1, and NR3C2 receptors and FKBP5 in the susceptibility to the comorbidity of depression, T2D, and MetS. New studies are needed to confirm the hypothesized role of these genes in the clinical association of depression, T2D, and MetS.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) is associated with an increase in the risk of major depressive disorder.Citation1,Citation2 Conversely, depression confers a 60% increased T2D risk.Citation3 This association between depression and T2D cannot be attributed to antidepressant therapy.Citation4 T2D is associated with metabolic syndrome (MetS), and T2D, MetS, and depression are associated with high cortisol levels.Citation5–Citation9 It is possible that neuroendocrine dysfunction in depression increases the risk for T2D and MetS, and that inherited gene variants involved in stress responses might account, at least in part, for the comorbidity of depression with T2D and MetS.Citation6,Citation10,Citation11

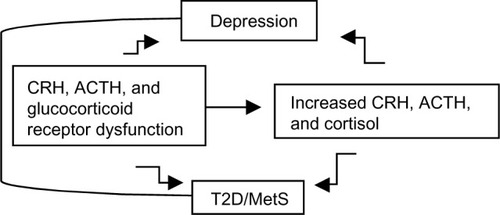

In fact, considerable evidence suggests that genetic vulnerability to depression may be conferred by variation in genes regulating systems of stress response,Citation12,Citation13 such as the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis.Citation14,Citation15 The HPA axis is a neuroendocrine system modulating the stress response via interactions with serotonergic, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic brain systems. Stress leads to high cortisol levels; under stress, the HPA axis releases corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) to stimulate adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) secretion via the CRH receptor (CRHR) from the anterior pituitary, thereby elevating cortisol. The CRHRs (CRHR1 and CRHR2) and the melanocortin receptors (MC1R–MC5R) mediate the axis responsiveness to integrated signals from diurnal rhythms, cortisol negative feedback via the glucocorticoid receptor, and superimposed stressors. Recently, MC2R variants leading to strong responses to ACTH have been described.Citation16 Further, MC4R variants causing functional impairment have been reported.Citation17 Increased cortisol causes serotonergic dysfunction, which is a substrate for depression.Citation12 While acute stress with associated cortisol levels is a physiological phenomenon, persistent or chronic stress associated with persistent or chronic hypercortisolism may lead to a pathological condition. Hypercortisolism and altered feedback inhibition are HPA abnormalities of depression, T2D, and MetS ().Citation7–Citation9,Citation18 Depressed patients, given their hypercortisolism and compared to control subjects, have inappropriately “normal” plasma ACTH and cerebrospinal fluid CRH;Citation19 that is, their levels should be lower in the presence of high cortisol, which triggers a negative feedback at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, thereby reducing CRH and ACTH. Thus CRHR, ACTH receptor, and glucocorticoid receptor dysfunctions are possible. Several of these HPA axis receptor genes are associated with metabolic abnormalities; the known physiologic effects of glucocorticoids suggest that inherited predisposition to HPA axis activation may contribute to glucose intolerance,Citation20 visceral obesity, and increased triglycerides and blood pressure.Citation21,Citation22

Figure 1 Hypothesized relationship between CRH, ACTH, and glucocorticoid receptors dysfunction, increased CRH, ACTH and cortisol levels, depression, T2D, and MetS.

It is possible that common gene pathways are responsible for the association of depression with T2D and MetS and that genetic variation in the HPA axis receptors may explain the link between depression, T2D, and MetS.

T2D, MetS, and depression and possible genetic stratification for their comorbidity

T2D (with 11% prevalence after age 50),Citation23 MetS (with 42% prevalence after age 60),Citation24 and depression (with 9% prevalence in adults)Citation25 are heterogeneous polygenic and complex disorders and they are often comorbid. T2D is defined by at least two fasting glucose levels ≥126 mg/dL or a glucose level of 200 mg/dL at 2 hours of the oral glucose tolerance test or by a random glucose level of 200 mg/dL associated with symptoms. MetS is defined by the National Cholesterol Education Program (2002) Adult Treatment Panel III as the presence of at least three of the following: abdominal obesity (waist circumference in men >102 cm, in women >88 cm), high triglycerides (≥150 mg/dL), low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (HDL <40 mg/dL in men, <50 mg/dL in women), high blood pressure (≥130/85 mmHg and/or on antihypertensive medications), and high fasting glucose (≥110 mg/dL and/or on antidiabetic medications). Visceral fat deposition, high blood pressure, and hyperglycemia are all aging phenomena.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) criteria for major depressive disorder (depression) are: presence of depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities for more than 2 weeks; mood change from the person’s baseline; impaired function at least either social or occupational or educational. Further, at least five of the following nine symptoms must be present nearly every day: depressed or irritable mood most of the day, nearly every day, per either subjective report (eg, the patient feels sad or empty) or observation made by others (eg, appears tearful); decreased interest or pleasure in most activities, most of each day; significant weight change (5%) or change in appetite; change in sleep: insomnia or hypersomnia; change in activity: psychomotor agitation or retardation; fatigue or loss of energy; guilt or worthlessness: feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt; concentration: diminished ability to think or concentrate, or more indecisiveness; and suicidality: thoughts of death or suicide, or the patient has a suicide plan.

Both the serotonergic and HPA system are implicated in depressionCitation26 and both may play a role in T2D and MetS.Citation6,Citation27,Citation28 Thus, it is unlikely that a single pathway or a few genes in a specific pathway will explain any one of these three disorders or their comorbidity. We believe that there is a genetic stratification in comorbid-diseases predisposition correlated to phenotype heterogeneity. As not all depressed patients develop T2D and MetS, and not all patients with T2D and MetS have depression, different gene pathways will be responsible for each disorder independently, but the HPA axis function and underlying genes could be related to the symptoms and signs of depression and potentially contributing to the increased risk for T2D and MetS. However, the genetic risk conferred by the HPA axis pathway for the comorbidity of depression, T2D, and MetS is expected to be stratified in patient groups and to correlate with sub-phenotypes of T2D, MetS, and depression. An investigational study of the correlation of the HPA-axis-related genes with the phenotype(s) of T2D, MetS, and depression, or the lack thereof, may elucidate the genetic basis of the T2D and MetS association with depression. Such an investigational study will provide the foundation upon which other data and pathogenetic hypotheses could subsequently be built.

Novelty of hypothesis and new investigational needs

Our hypothesis for the potential link of depression with T2D and MetS challenges the currently accepted paradigm that T2D and MetS are only metabolic disorders, and that depression is only a mental disorder. In fact, we believe that they are all, at least partially and in the subgroup of patients with T2D, MetS, and depression comorbidity, associated with hyperactivity of the neuroendocrine cortisol pathway. There are no extensive data regarding genetic screening of the HPA axis receptor genes jointly exploring T2D, MetS, and depression traits in humans. It would be a powerful and innovative strategy for gene risk identification to perform linkage and association tests not only in a group of patients with T2D, MetS, and depression, but also with the pre-phenotypes and associated mental traits potentially contributing to these diseases. The hypothesis is that T2D and MetS are not merely disorders affecting glucose levels, lipid levels, and blood pressure, rather they are complex disorders characterized by increased predisposition to stress-related hyperactivity and abnormal psychological traits leading to abnormal behavioral and compensatory mechanisms.

Ideally, the impact of single and/or complex gene variants should be tested in the major traits as well as in the sub-phenotypes of these two apparently distinct disorder groups of T2D-MetS and depression. There is a need to test not just genotypes and alleles of candidate genes, but also haplotypes, diplotypes, and multilocus alleles to prove the risk effects of complex gene variants in common disorders.

A linkage strategy would be helpful in identifying rare variants rather than common variants as major players in the diseases’ causes.Citation29 Also, the interaction among gene variants should be tested.

To test the abovementioned hypothesis, it would be essential to build an interdisciplinary approach of human genetics and clinical phenotyping of T2D and MetS with a focus on depression and related traits and to perform a joint study of the HPA axis receptor genes in both human T2D and MetS with the depression phenotypes.

Implication of the HPA axis and related candidate genes in the pathogenesis of the comorbidity of T2D, MetS, and depression

High cortisol increases glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, insulin resistance, free fatty acids, and visceral obesity, and indirectly and directly reduces insulin secretion; all these effects per se and jointly lead to T2DCitation20 and MetS. High cortisol may cause depressive symptoms as wellCitation30,Citation31 and stress plays a major role in depression: early life stress (eg, separation anxiety at an early life stage)Citation32 associated with HPA axis hyperactivationCitation14 induces long-lasting changes linked to adult anxiety and depressive behavior.Citation33 While some subjects thrive and some break down under similar adverse circumstances due to neuroendocrine stress-related psychopathology, differential genetic predisposition to neuroendocrine stress response is expected. The CRH system plays a role in the stress response of depressionCitation13,Citation15 and CRH single nucleotide polymorphisms are depression risk variants.Citation15 The CRH system resistance leads to hypercortisolism. A subgroup of hypercortisolemic patients with depression, if stimulated with CRH, show a blunted ACTH response, whereas CRH infusion to healthy subjects reproduces the hypercortisolism of depression, suggesting that hypercortisolism in depression represents a defect at the CRHR level, resulting in CRH hypersecretion.Citation34 Furthermore, a significant cortisol response to a blunted ACTH response suggests that the adrenal glands hyper-respond to ACTH. Thus, there may be an ACTH receptor abnormality as well.Citation35 Aging is associated with both the HPA axis reduced feedback and hyperactivity,Citation36 which could be due to glucocorticoid receptor resistance, and may lead to T2D, MetS, and depression. However, depression prevalence decreases with age. Consequentially, the stress response pathway may lead to the T2D–depression and MetS–depression comorbidity. The genes possibly conferring predisposition to the clinical association of T2D, MetS, and depression are the CRHRs (CRHR1 and CRHR2), the corticotropin receptors or melanocortin receptors (MC1R–MC5R), the glucocorticoid receptor (GCR), the mineralocorticoid receptor (MCR), and the FK506 binding protein 51 (FKBP5) ().

Table 1 Candidate genes, their locus and linkage data, and related risk human phenotypes

The CRHR1 gene is expressed in the brain. CRHR1−/− mice show reduced anxiety behavior.Citation37,Citation38 CRHR1 variants are implicated in human depressionCitation39–Citation42 and antidepressant response.Citation43,Citation44 However, there are no studies in human T2D and MetS. CRHR1 is expressed on beta cells and stimulates beta cell proliferation and insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner;Citation45 some CRHR1 variants are associated with hypertension,Citation46 thus CRHR1 dysfunction may lead to hyperglycemia, T2D, and high blood pressure of MetS. Interestingly, the CRHR1 genetic locus 17q12 is linked to T2DCitation47 and MetS.Citation48

The CRHR2 gene is also expressed in the brain. CRHR2−/− mice have reduced stress coping behaviorsCitation49 and show hypersensitivity to stress and anxiety behavior.Citation50,Citation51 CRHR2 is not yet identified as a risk gene in human depression,Citation52 T2D, or MetS. However, previous studies report the CRHR2 locus 7p21-p15 in linkage with depressionCitation53 and bipolar disorder.Citation54,Citation55 Of note, genetic overlap exists between bipolar disorder and depression.Citation56 The CRHR2 genetic locus 7p21-p15 is also linked to T2D,Citation57,Citation58 glycemia, triglyceride, and HDL levels.Citation59 CRHR2−/− mice show high blood pressure and reduced sustained hypophagia;Citation49 thus CRHR2 variants may lead to high blood pressure and obesity of MetS, the latter potentially due to impaired mediation of food intake control.

The corticotropin receptor or melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) gene is expressed in the brain, liver, and pancreas, and is implicated in depression and antidepressant response.Citation60 However, there are no studies in human genetics of T2D or MetS. The MC1R genetic locus 16q24 is linked to bipolar disorder,Citation61,Citation62 T2D nephropathy,Citation63 and left ventricular thickness in the setting of MetS.Citation64

The corticotropin receptor or melanocortin 2 receptor (MC2R) gene is expressed in the brain and adrenal gland; MC2R mutations cause hypoglycemia and glucocorticoid deficiency.Citation65 There is a lack of studies in human depression and T2D. The MC2R genetic locus 18p11 is linked to bipolar disorder,Citation67–Citation70 T2D, insulin, obesity, and body mass index (BMI).Citation71–Citation75

The corticotropin receptor or melanocortin 3 receptor (MC3R) gene is expressed in the hypothalamus and brain; it is involved in obesityCitation76,Citation77 and may play a role in human T2D.Citation66,Citation78 MC3R−/− mice have increased adipose mass;Citation79 MC3R variants may protect against weight and blood pressure increase.Citation80 There are no studies in human MetS and depression. The MC3R genetic locus 20q13.2 is linked to bipolar disorder,Citation55 T2D,Citation81–Citation83 and early-onset hypertension in African Americans.Citation84

The corticotropin receptor or melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) gene is expressed in the brain; it is involved in hyperphagia and increased BMI,Citation85 as well as T2D,Citation86–Citation89 but data are inconsistent.Citation90,Citation91 Some MC4R variants are implicated in weight regulation and BMI.Citation92,Citation93 MC4R is also implicated in depression.Citation94 The MC4R genetic locus 18q22 is linked to depression,Citation53 bipolar disorder,Citation67,Citation69 and T2D.Citation71 It is known that 18q22 deletion causes metabolic defects.Citation95 The 18q22 locus affects glycemia,Citation96 is linked to hypertriglyceridemia,Citation97 and is associated with fat mass.Citation98

The corticotropin receptor or melanocortin 5 receptor (MC5R) gene is expressed in the brain and has a role in T2D.Citation66 MC5R variants are associated with BMI.Citation98 There is a lack of studies regarding depression. The MC5R genetic locus 18p11 is linked to bipolar disorder,Citation67–Citation69 T2D,Citation71–Citation73 BMI,Citation75 obesity, and insulin.Citation74

The glucocorticoid receptor gene or nuclear receptor sub-family 3, group C, member 1 (GCR or NR3C1), expressed ubiquitously, and the mineralocorticoid receptor gene or nuclear receptor sub-family 3, group C, member 2 (MCR or NR3C2), expressed in multiple tissues including the central nervous system and the hippocampus, may also predispose to the T2D, MetS, and depression comorbidity. Glucocorticoids mediate the HPA axis negative feedback via the GCR at the hypothalamus and pituitary level. Cortisol has effects on both MCR and GCR. Of note, the GCR locus 5q31 is associated to hypertensionCitation99 and linked to bipolar disorder.Citation100 The MCR locus chromosome 4q31.1-31.2 is linked to T2D and MetSCitation101 and to bipolar disorder.Citation102–Citation105 MCR and GCR variants affect coping style and depression vulnerability, antidepressants response, stress, and depression endocrine response.Citation106–Citation115 MCR expression is increased in the hypothalamus of diabetic ratsCitation116 and MCR is linked to blood pressure.Citation117 GCR affects glucose levelsCitation118 and is associated with insulin resistance;Citation119 GCR antagonism improves insulin sensitivity.Citation120 Thus, GCR and MCR dysfunction may lead to depression, T2D, and MetS, and contribute to the comorbidity of these three disorders.

In addition, the FK506 binding protein 5 (FKBP5), a heat shock protein 90 co-chaperone of the steroid receptor complex and component of the chaperone receptor heterocomplex, reduces ligand sensitivity of the GCRCitation121 and is implicated in cortisol effects. Interestingly, the FKBP5 gene locus 6p21.31 is associated to T2DCitation122 and linked to obesity,Citation123 blood pressure,Citation124 and bipolar disorder.Citation125 The gene FKBP5 is therefore a candidate gene for the comorbidity of T2D, MetS, and depression. FKBP5 has in fact been implicated in depressionCitation126,Citation127 and antidepressant response,Citation128 even if results for antidepressant response are conflicting.Citation129 There are not yet data on FKBP5 and T2D and MetS.

For all the above-mentioned reasons, these genes alone or jointly may confer the genetic susceptibility to the HPA axis hyperactivation under stressful circumstance and cause depression and confer increased risk for the T2D and MetS phenotypes.

Suggested methods to empower gene identification for the comorbidity of depression, T2D, and MetS

Families phenotyping

Ideally, to identify the gene variants in the HPA axis receptor genes responsible for the clinical association of depression, T2D, and MetS, families with all three disorders, as well with only two and one disorder, should be studied. At best, recruiting families with early onset of disease phenotypes and their comorbidity will increase the genetic load for risk predisposition and the probability to discover the susceptibility gene variants. The families should be characterized not only for depression but also for associated traits such as anxiety, insomnia, symptom duration and severity, substance abuse and dependence, life stress level, and resilience. The cases should be characterized for disease severity, age of onset, associated mental comorbidities, subtype of melancholic depression and atypical depression, to empower gene identification strategy and to link risk gene variants to specific traits. Melancholic depression is characterized by the following: depressed mood; anhedonia as per loss of pleasure in most or all activities, inability to react to pleasurable stimuli; insomnia or early-morning waking; symptom worsening in the morning hours; psychomotor agitation or retardation; excessive or inappropriate guilt, worthlessness; fatigue; decreased appetite and excessive weight loss; and inattention or poor concentration. Atypical depression is characterized by the following: improved mood in response to positive events; irritable-anxious mood; increased appetite as per comfort eating or significant weight gain; sensation of heaviness in the limbs; hypersomnia as per excessive sleep or sleepiness; over-sensitivity to perceived interpersonal rejection causing significant social impairment.Citation130

Similarly the families should not only be characterized for T2D but also for all the T2D-associated common phenotypes, including, but not only, behavioral and compensatory mechanisms related to stress, nutrition, and physical exercise. In the characterization of MetS, beyond the classical features of MetS, other potentially associated traits should be included; for example psychological traits, behavioral traits, nutrition and exercise preferences, sleep duration and quality, and quality of life.

Linkage and association tests

By characterizing the families with all three disorders, and with only two or one of them, as well as defining new groups of traits potentially associated with the disease comorbidity, it would then be feasible to create different categories of joint endophenotypes and traits and to test them for linkage and association with the gene variants under study. The creation of categories with T2D and melancholic or atypical depression or both or with specific depression traits (eg, anhedonia, insomnia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, decreased appetite), psychoactive medication intake, earlier age of onset, extreme phenotype severity, and life stress level, will enrich the genetic load and likelihood for stress-related risk-gene identification, which could be compared with one category with either only T2D or a depression trait. Similarly, it would be helpful to test gene variants for linkage with MetS (as traditionally defined) as well as for just single phenotypes of high blood pressure, visceral obesity, high triglycerides, and low HDL, and for the positivity of only two phenotypes; and for the additional presence of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and therapy with antipsychotics, antidepressants, and anxiolytics. To increase the probability of discovering risk-genes, the linkage tests should also be performed on a group of families with severe MetS by including at least four positive criteria as well as increasing the criteria threshold (eg, BMI >35, blood pressure >160/95 mmHg, and triglycerides >200 mg/dL), with the addition of depression, anxiety, insomnia, psychotropic medications, and high level of stress. By creating a subject category for multiple MetS–depression traits, the probability that those families will carry the gene variants related to chronic stress vulnerability and HPA axis hyperactivation will be greater, as well as the chance to identify those gene variants compared to: either a category with only two MetS traits; or one MetS trait or depression trait; or neither MetS nor a depression trait.

Another helpful method to identify the gene variants responsible for the comorbidity of depression, T2D, and MetS is to perform variance-component trait analyses for each quantitative trait associated with T2D and mental–behavioral traits (eg, stress, sleep duration and quality, diet, physical activity, and medication compliance), using the other available traits as covariates. The metabolic quantitative traits for T2D could be basal glucose levels at T2D onset, average glycated hemoglobin 1c % (Hba1c%) levels, total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein levels, age at disease onset, BMI at onset, and years of therapy defined by diet only, oral hypoglycemic agents only, insulin only, and insulin combined with oral hypoglycemic agents. For the MetS phenotype, the quantitative traits could be blood pressure, waist circumference, maximum life BMI, triglycerides, HDL, and glucose levels, both independently and by using these traits as covariates with age and sex. Further, phenotypes of depression, anxiety, insomnia and, psychotropic medication, could be used as covariates. Another approach could be to test gene variants for linkage with a newly created quantitative scale with: depression, anxiety, insomnia, psychotropic medication use, pre-diabetes, T2D, hypertension, high triglycerides, low HDL, and visceral obesity. For the depression phenotype, the quantitative traits could be age of onset, number of DSM-V criteria met, quantification of severity of episodes, associated mental diseases, and treatment types and years of antidepressant therapy.

Both linkage and association tests should be performed using the nonparametric and parametric methods and data should be validated with random simulations. Linkage analysis should also be conditioned on the presence of already identified loci.

The association tests should be performed with alleles, genotypes, haplotypes, and diplotypes; in fact when two or more adjacent single variant polymorphisms are considered, haplotype analysis is crucial since single variant polymorphisms may affect complex traits acting as cis-regulatory elements. In addition, haplotype analysis is more powerful than single variant polymorphisms analysis.Citation131 Epistatic interaction ought to be studied as well, as a disorder often involves a multifactorial underpinning to which many genes contribute, and evidence shows that the effects of some genes are not additive; rather, the effects are via interactions or epistasis.Citation132,Citation133 Because of epistasis, two or more genes may increase or reduce disease risk more than expected from their independent effects.

If large case–control groups are used, to avoid false negative associations, association tests should be performed with case subjects positive for comorbid diseases or a trait category against control subjects negative for those comorbid diseases or trait category. In fact, if a gene variant causes depression, T2D, and MetS, it would be difficult to identify it by association unless the case group is enriched of those phenotypes and the control group is unaffected by all those phenotypes. For disease-associated quantitative traits (eg, Hba1c%), logistic regression analysis should be performed.

If association is not identified, the tests should be repeated with the probands of only the families showing a positive linkage, in order to increase the likelihood of gene identification. In fact, those families with a positive linkage are more likely to carry the disease variant and to highlight a positive association if tested against a control group.Citation134

T2D–depression and MetS–depression reciprocity

The T2D and depression association should be, for some genes and gene variants and with different significance levels, comparable to the MetS and depression association. However, some discordance is expected that, if identified, could guide into gene risk stratification for the T2D, MetS, and depression comorbidity. Thus, while some families with T2D–depression and/or MetS–depression will have shared gene-risk vulnerability within the cortisol pathway, other families will not show genetic susceptibility within the cortisol pathway and will likely present phenotype differences.

However, for the gene variants not contributing to the T2D–depression and MetS–depression association, linkage and association within just T2D–MetS or depression could be present. Ultimately, some genes and gene variants will contribute neither to T2D–MetS comorbidity with depression nor to T2D–MetS or depression. In fact, some variability in the genetic burden of T2D, MetS, and depression is expected, and once identified will help in defining more homogeneous clinical phenotypes for future studies by increasing gene risk detection power.

Other studies and possible outcomes

It would be interesting to set up epigenetic studies to explore in depth the hypothesis that stress may indeed induce functional regulatory changes in the abovementioned candidate genes, which may per se lead to hypercortisolism and to the comorbidity of depression, T2D, and MetS. Furthermore, to fully assess the impact of depression on T2D and MetS and study the comorbidity and interaction of these three disorders phenomenon, it would be ideal to perform longitudinal studies to determine the conferring risk of one disorder onto the other.

The final goal of our proposed studies would be to implement preventive plans targeting subjects identified at risk for T2D, MetS, and depression, who, by knowing their genetic make-up and risk for such disorders, may be inclined to undergo behavioral–cognitive therapy treatments and lifestyle modifying behaviors. Such preventive plans may significantly decrease the burden of T2D, MetS, and depression comorbidity on subjects and on the health care system. In the long-term, it would be possible to therapeutically target the receptors implicated in the HPA axis disruption in subjects at risk for T2D, MetS, and depression, thereby reversing the HPA axis hyperactivity to a physiological state, and preventing the comorbidity of T2D, MetS, and depression. The results of a study targeting the abovementioned comorbidity should prompt new research in the area of associated mental and metabolic disorders, thereby creating a new focus on the neuroendocrine–mental–metabolic dysfunctions, which may characterize pre-disease states. In order to advance the research in the field of T2D, MetS, and depression, there is a need to accept the idea of a joint pathogenesis of such apparently different disorders.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DemakakosPPierceMBHardyRDepressive symptoms and risk of type 2 diabetes in a national sample of middle-aged and older adults: the English longitudinal study of agingDiabetes Care201033479279720086253

- RustadJKMusselmanDLNemeroffCBThe relationship of depression and diabetes: Pathophysiological and treatment implicationsPsychoneuroendocrinology20113691276128621474250

- MezukBEatonWWAlbrechtSGoldenSHDepression and type 2 diabetes over the lifespan: a meta-analysisDiabetes Care200831122383239019033418

- PanALucasMSunQBidirectional association between depression and type 2 diabetes mellitus in womenArch Intern Med2010170211884189121098346

- MangoldDMarinoEJavorsMThe cortisol awakening response predicts subclinical depressive symptomatology in Mexican American adultsJ Psychiatr Res201145790290921300376

- VogelzangsNSuthersKFerrucciLHypercortisolemic depression is associated with the metabolic syndrome in late-lifePsychoneuroendocrinology200732215115917224244

- BjörntorpPThe origins and consequences of obesity. DiabetesCiba Found Symp19962016880 discussion 80–89, 188–1939017275

- BruehlHRuegerMDziobekIHypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation and memory impairments in type 2 diabetesJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20079272439244517426095

- VinsonGPAngiotensin II, corticosteroids, type II diabetes and the metabolic syndromeMed Hypotheses20076861200120717134848

- BjörntorpPHolmGRosmondRHypothalamic arousal, insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes mellitusDiabet Med199916537338310342336

- WolkowitzOMReusVIMellonSHOf sound mind and body: depression, disease, and accelerated agingDialogues Clin Neurosci2011131253921485744

- PompiliMSerafiniGInnamoratiMThe hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and serotonin abnormalities: a selective overview for the implications of suicide preventionEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci2010260858360020174927

- KeckMECorticotropin-releasing factor, vasopressin and receptor systems in depression and anxietyAmino Acids200631324125016733617

- NaertGIxartGMauriceTTapia-ArancibiaLGivaloisLBrain-derived neurotrophic factor and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis adaptation processes in a depressive-like state induced by chronic restraint stressMol Cell Neurosci2011461556620708081

- BaoAMSwaabDFCorticotropin-releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin in depression focus on the human postmortem hypothalamusVitam Horm20108233936520472147

- DingYXZouLPHeBYueWHLiuZLZhangDACTH receptor (MC2R) promoter variants associated with infantile spasms modulate MC2R expression and responsiveness to ACTHPharmacogenet Genomics2010202717620042918

- HinneyABetteckenTTarnowPPrevalence, spectrum, and functional characterization of melanocortin-4 receptor gene mutations in a representative population-based sample and obese adults from GermanyJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20069151761176916492696

- ZunszainPAAnackerCCattaneoACarvalhoLAParianteCMGlucocorticoids, cytokines and brain abnormalities in depressionProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry201135372272920406665

- WongMLKlingMAMunsonPJPronounced and sustained central hypernoradrenergic function in major depression with melancholic features: relation to hypercortisolism and corticotropin-releasing hormoneProc Natl Acad Sci U S A200097132533010618417

- PivonelloRDe LeoMVitalePPathophysiology of diabetes mellitus in Cushing’s syndromeNeuroendocrinology201092Suppl 1778120829623

- WalleriusSRosmondRLjungTHolmGBjörntorpPRise in morning saliva cortisol is associated with abdominal obesity in men: a preliminary reportJ Endocrinol Invest200326761661914594110

- WeigensbergMJToledo-CorralCMGoranMIAssociation between the metabolic syndrome and serum cortisol in overweight Latino youthJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20089341372137818252788

- MokdadAHFordESBowmanBAPrevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001JAMA20032891767912503980

- FordESGilesWHDietzWHPrevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyJAMA2002287335635911790215

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionCurrent depression among adults – United States, 2006 and 2008MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep201059381229123520881934

- LanfumeyLMongeauRCohen-SalmonCHamonMCorticosteroid-serotonin interactions in the neurobiological mechanisms of stress-related disordersNeurosci Biobehav Rev20083261174118418534678

- PriceJCKelleyDERyanCMEvidence of increased serotonin-1A receptor binding in type 2 diabetes: a positron emission tomography studyBrain Res200292719710311814436

- SilićAKarlovićDSerrettiAIncreased inflammation and lower platelet 5-HT in depression with metabolic syndromeJ Affect Disord20121411727822391518

- DicksonSPWangKKrantzIHakonarsonHGoldsteinDBRare variants create synthetic genome-wide associationsPLoS Biol201081e100029420126254

- VogelzangsNBeekmanATDikMGLate-life depression, cortisol, and the metabolic syndromeAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200917871672119625789

- VogelzangsNPenninxBWDepressive symptoms, cortisol, visceral fat and metabolic syndromeTijdschr Psychiatr2011539613620 Dutch21898316

- BrandSWilhelmFHKossowskyJHolsboer-TrachslerESchneiderSChildren suffering from separation anxiety disorder (SAD) show increased HPA axis activity compared to healthy controlsJ Psychiatr Res201145445245920870248

- KolberBJBoyleMPWieczorekLTransient early-life forebrain corticotropin-releasing hormone elevation causes long-lasting anxiogenic and despair-like changes in miceJ Neurosci20103072571258120164342

- GoldPWKlingMAKhanICorticotropin releasing hormone: relevance to normal physiology and to the pathophysiology and differential diagnosis of hypercortisolism and adrenal insufficiencyAdv Biochem Psychopharmacol1987431832003035886

- ClarkAJMetherellLAMechanisms of disease: the adrenocorticotropin receptor and diseaseNat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab20062528229016932299

- BjörntorpPAlterations in the ageing corticotropic stress-response axisNovartis Found Symp20022424658 discussion 58–6511855694

- TimplPSpanagelRSillaberIImpaired stress response and reduced anxiety in mice lacking a functional corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1Nat Genet19981921621669620773

- SmithGWAubryJMDelluFCorticotropin releasing factor receptor 1-deficient mice display decreased anxiety, impaired stress response, and aberrant neuroendocrine developmentNeuron1998206109311029655498

- HeimCBradleyBMletzkoTCEffect of Childhood Trauma on Adult Depression and Neuroendocrine Function: Sex-Specific Moderation by CRH Receptor 1 GeneFront Behav Neurosci200934120161813

- ResslerKJBradleyBMercerKBPolymorphisms in CRHR1 and the serotonin transporter loci: gene x gene x environment interactions on depressive symptomsAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2010153B381282420029939

- WassermanDWassermanJRozanovVSokolowskiMDepression in suicidal males: genetic risk variants in the CRHR1 geneGenes Brain Behav200981727919220485

- LiuZZhuFWangGAssociation of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor1 gene SNP and haplotype with major depressionNeurosci Lett2006404335836216815632

- LicinioJO’KirwanFIrizarryKAssociation of a corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 haplotype and antidepressant treatment response in Mexican-AmericansMol Psychiatry20049121075108215365580

- LiuZZhuFWangGAssociation study of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor1 gene polymorphisms and antidepressant response in major depressive disordersNeurosci Lett2007414215515817258395

- HuisingMOvan der MeulenTVaughanJMCRFR1 is expressed on pancreatic beta cells, promotes beta cell proliferation, and potentiates insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent mannerProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2010107291291720080775

- KamdemLKHamiltonLChengCGenetic predictors of glucocorticoid-induced hypertension in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemiaPharmacogenet Genomics200818650751418496130

- SpurdleABThompsonDJAhmedSAustralian National Endometrial Cancer Study Group; National Study of Endometrial Cancer Genetics GroupGenome-wide association study identifies a common variant associated with risk of endometrial cancerNat Genet201143545145421499250

- ChengCYLeeKEDuggalPGenome-wide linkage analysis of multiple metabolic factors: evidence of genetic heterogeneityObesity (Silver Spring)201018114615219444228

- CosteSCKestersonRAHeldweinKAAbnormal adaptations to stress and impaired cardiovascular function in mice lacking corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-2Nat Genet200024440340910742107

- BaleTLContarinoASmithGWMice deficient for corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-2 display anxiety-like behaviour and are hypersensitive to stressNat Genet200024441041410742108

- KishimotoTRadulovicJRadulovicMDeletion of crhr2 reveals an anxiolytic role for corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-2Nat Genet200024441541910742109

- VillafuerteSMDel-FaveroJAdolfssonRGene-based SNP genetic association study of the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-2 (CRHR2) in major depressionAm J Med Genet2002114222222611857585

- CampNJLowryMRRichardsRLGenome-wide linkage analyses of extended Utah pedigrees identifies loci that influence recurrent, early-onset major depression and anxiety disordersAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2005135B1859315806581

- KremeyerBGarciaJMullerHGenome-wide linkage scan of bipolar disorder in a colombian population isolate replicates Loci on chromosomes 7p21-22, 1p31, 16p12 and 21q21-22 and identifies a novel locus on chromosome 12qHum Hered201070425526821071953

- HamshereMLSchulzeTGSchumacherJMood-incongruent psychosis in bipolar disorder: conditional linkage analysis shows genome-wide suggestive linkage at 1q32.3, 7p13 and 20q13.31Bipolar Disord200911661062019689503

- PregeljPPsychosis and depression – a neurobiological viewPsychiatr Danub200921Suppl 110210519789492

- WiltshireSHattersleyATHitmanGAA genomewide scan for loci predisposing to type 2 diabetes in a UK population (the Diabetes UK Warren 2 Repository): analysis of 573 pedigrees provides independent replication of a susceptibility locus on chromosome 1qAm J Hum Genet200169355356911484155

- LeakTSLangefeldCDKeeneKLChromosome 7p linkage and association study for diabetes related traits and type 2 diabetes in an African-American population enriched for nephropathyBMC Med Genet2010112220144192

- TamCHLamVKSoWYMaRCChanJCNgMCGenome-wide linkage scan for factors of metabolic syndrome in a Chinese populationBMC Genet2010111420181263

- WuGSLuoHRDongCMastronardiCLicinioJWongMLSequence polymorphisms of MC1R gene and their association with depression and antidepressant responsePsychiatr Genet2011211141821052032

- ChengRJuoSHLothJEGenome-wide linkage scan in a large bipolar disorder sample from the National Institute of Mental Health genetics initiative suggests putative loci for bipolar disorder, psychosis, suicide, and panic disorderMol Psychiatry200611325226016402137

- HaydenEPNurnbergerJIJrMolecular genetics of bipolar disorderGenes Brain Behav200651859516436192

- ChenGAdeyemoAAZhouJA genome-wide search for linkage to renal function phenotypes in West Africans with type 2 diabetesAm J Kidney Dis200749339440017336700

- KrajaATHuangPTangWQTLs of factors of the metabolic syndrome and echocardiographic phenotypes: the hypertension genetic epidemiology network studyBMC Med Genet2008910319038053

- ClarkAJMcLoughlinLGrossmanAFamilial glucocorticoid deficiency associated with point mutation in the adrenocorticotropin receptorLancet199334188434614628094489

- Valli-JaakolaKSuviolahtiESchalin-JanttiCFurther evidence for the role of ENPP1 in obesity: association with morbid obesity in FinnsObesity (Silver Spring)20081692113211918551113

- BaronMManic-depression genes and the new millennium: poised for discoveryMol Psychiatry20027434235811986978

- Detera-WadleighSDBadnerJABerrettiniWHA high-density genome scan detects evidence for a bipolar-disorder susceptibility locus on 13q32 and other potential loci on 1q32 and 18p11.2Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A199996105604560910318931

- NothenMMCichonSRohlederHEvaluation of linkage of bipolar affective disorder to chromosome 18 in a sample of 57 German familiesMol Psychiatry199941768410089014

- SeguradoRDetera-WadleighSDLevinsonDFGenome scan meta-analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, part III: Bipolar disorderAm J Hum Genet2003731496212802785

- JunGSongYSteinCMIyengarSKAn autosome-wide search using longitudinal data for loci linked to type 2 diabetes progressionBMC Genet20034Suppl 1S814975076

- van TilburgJHSandkuijlLAFrankeLGenome-wide screen in obese pedigrees with type 2 diabetes mellitus from a defined Dutch populationEur J Clin Invest200333121070107414636289

- ParkerAMeyerJLewitzkySA gene conferring susceptibility to type 2 diabetes in conjunction with obesity is located on chromosome 18p11Diabetes200150367568011246890

- KrajaATRaoDCWederABTwo major QTLs and several others relate to factors of metabolic syndrome in the family blood pressure programHypertension200546475175716172425

- ShmulewitzDHeathSCBlundellMLLinkage analysis of quantitative traits for obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia on the island of Kosrae, Federated States of MicronesiaProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2006103103502350916537441

- FengNYoungSFAguileraGCo-occurrence of two partially inactivating polymorphisms of MC3R is associated with pediatric-onset obesityDiabetes20055492663266716123355

- MencarelliMWalkerGEMaestriniSSporadic mutations in melanocortin receptor 3 in morbid obese individualsEur J Hum Genet200816558158618231126

- HaniEHDupontSDurandENaturally occurring mutations in the melanocortin receptor 3 gene are not associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in French CaucasiansJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20018662895289811397906

- ButlerAAKestersonRAKhongKA unique metabolic syndrome causes obesity in the melanocortin-3 receptor-deficient mouseEndocrinology200014193518352110965927

- YakoYYFanampeBLHassanSMErasmusRTvan der MerweLMatshaTENegative association of MC3R variants with weight and blood pressure in Cape Town pupils aged 11–16 yearsS Afr Med J2011101641742021920079

- KlupaTMaleckiMTPezzolesiMFurther evidence for a susceptibility locus for type 2 diabetes on chromosome 20q13.1-q13.2Diabetes200049122212221611118028

- BentoJLPalmerNDZhongMHeterogeneity in gene loci associated with type 2 diabetes on human chromosome 20q13.1Genomics200892422623418602983

- ZoualiHHaniEHPhilippiAA susceptibility locus for early-onset non-insulin dependent (type 2) diabetes mellitus maps to chromosome 20q, proximal to the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase geneHum Mol Genet199769140114089285775

- FreedmanBILangefeldCDRichSSA genome scan for ESRD in black families enriched for nondiabetic nephropathyJ Am Soc Nephrol200415102719272715466277

- LuanJKernerBZhaoJHA multilevel linear mixed model of the association between candidate genes and weight and body mass index using the Framingham longitudinal family dataBMC Proc20093Suppl 7S11520017980

- ButlerAAConeRDThe melanocortin receptors: lessons from knockout modelsNeuropeptides2002362–3778412359499

- WenJRonnTOlssonAInvestigation of type 2 diabetes risk alleles support CDKN2A/B, CDKAL1, and TCF7L2 as susceptibility genes in a Han Chinese cohortPLoS One201052e915320161779

- QiLKraftPHunterDJHuFBThe common obesity variant near MC4R gene is associated with higher intakes of total energy and dietary fat, weight change and diabetes risk in womenHum Mol Genet200817223502350818697794

- MergenMMergenHOzataMOnerROnerCA novel melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) gene mutation associated with morbid obesityJ Clin Endocrinol Metab2001867344811443223

- OhshiroYSankeTUedaKMolecular scanning for mutations in the melanocortin-4 receptor gene in obese/diabetic JapaneseAnn Hum Genet199963Pt 648348711246450

- ZakelUAWudySAHeinzel-GutenbrunnerMPrevalence of melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) mutations and polymorphismsin consecutively ascertained obese children and adolescents from a pediatric health care utilization populationKlin Padiatr20052174244249 German16032553

- PovelCMBoerJMOnland-MoretNCDolléMEFeskensEJvan der SchouwYTSingle nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) involved in insulin resistance, weight regulation, lipid metabolism and inflammation in relation to metabolic syndrome: an epidemiological studyCardiovasc Diabetol20121113323101478

- EwensKGJonesMRAnkenerWFTO and MC4R gene variants are associated with obesity in polycystic ovary syndromePLoS One201161e1639021283731

- ChakiSOkuyamaSInvolvement of melanocortin-4 receptor in anxiety and depressionPeptides200526101952196415979204

- SilvermanGASchneiderSSMassaHFThe 18q-syndrome: analysis of chromosomes by bivariate flow karyotyping and the PCR reveals a successive set of deletion breakpoints within 18q21.2-q22.2Am J Hum Genet19955649269377717403

- LiWDDongCLiDGarriganCPriceRAA quantitative trait locus influencing fasting plasma glucose in chromosome region 18q22-23Diabetes20045392487249115331565

- ShahSHKrausWECrossmanDCSerum lipids in the GENECARD study of coronary artery disease identify quantitative trait loci and phenotypic subsets on chromosomes 3q and 5qAnn Hum Genet200670Pt 673874817044848

- ChagnonYCChenWJPerusseLLinkage and association studies between the melanocortin receptors 4 and 5 genes and obesity-related phenotypes in the Quebec Family StudyMol Med19973106636739392003

- GuoYTomlinsonBChuTA genome-wide linkage and association scan reveals novel loci for hypertension and blood pressure traitsPLoS One201272e3148922384028

- HerzbergIJasinskaAGarciaJConvergent linkage evidence from two Latin-American population isolates supports the presence of a susceptibility locus for bipolar disorder in 5q31-34Hum Mol Genet200615213146315316984960

- BowdenDWRudockMZieglerJCoincident linkage of type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and measures of cardiovascular disease in a genome scan of the diabetes heart studyDiabetes20065571985199416804067

- XuHChengRJuoSHFine mapping of candidate regions for bipolar disorder provides strong evidence for susceptibility loci on chromosomes 7qAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2011156216817621302345

- KanevaRMilanovaVAngelichevaDBipolar disorder in the Bulgarian Gypsies: genetic heterogeneity in a young founder populationAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2009150B219120118444255

- SchumacherJKanevaRJamraRAGenomewide scan and fine-mapping linkage studies in four European samples with bipolar affective disorder suggest a new susceptibility locus on chromosome 1p35-p36 and provides further evidence of loci on chromosome 4q31 and 6q24Am J Hum Genet20057761102111116380920

- LiuJJuoSHDewanAEvidence for a putative bipolar disorder locus on 2p13-16 and other potential loci on 4q31, 7q34, 8q13, 9q31, 10q21-24, 13q32, 14q21 and 17q11-12Mol Psychiatry20038333334212660806

- DerijkRHde KloetERCorticosteroid receptor polymorphisms: determinants of vulnerability and resilienceEur J Pharmacol20085832–330331118321483

- DerijkRHvan LeeuwenNKlokMDZitmanFGCorticosteroid receptor-gene variants: modulators of the stress-response and implications for mental healthEur J Pharmacol20085852–349250118423443

- KlokMDVreeburgSAPenninxBWZitmanFGde KloetERDeRijkRHCommon functional mineralocorticoid receptor polymorphisms modulate the cortisol awakening response: Interaction with SSRIsPsychoneuroendocrinology201136448449420884124

- KumstaRMoserDStreitFKoperJWMeyerJWüstSCharacterization of a glucocorticoid receptor gene (GR, NR3C1) promoter polymorphism reveals functionality and extends a haplotype with putative clinical relevanceAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2009150B447648218663733

- LahtiJRäikkönenKBruceSGlucocorticoid receptor gene haplotype predicts increased risk of hospital admission for depressive disorders in the Helsinki birth cohort studyJ Psychiatr Res20114591160116421477816

- DeRijkRHde KloetERZitmanFGvan LeeuwenNMineralocorticoid receptor gene variants as determinants of HPA axis regulation and behaviorEndocr Dev20112013714821164267

- KlokMDGiltayEJVan der DoesAJA common and functional mineralocorticoid receptor haplotype enhances optimism and protects against depression in femalesTransl Psychiatry20111e6222832354

- SzczepankiewiczALeszczyńska-RodziewiczAPawlakJGlu-cocorticoid receptor polymorphism is associated with major depression and predominance of depression in the course of bipolar disorderJ Affect Disord20111341–313814421764460

- ZobelAJessenFvon WiddernOUnipolar depression and hippocampal volume: impact of DNA sequence variants of the glucocorticoid receptor geneAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2008147B683684318286599

- UherRHuezo-DiazPPerroudNGenetic predictors of response to antidepressants in the GENDEP projectPharmacogenomics J20099422523319365399

- JöhrenODendorferADominiakPRaaschWGene expression of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors in the limbic system is related to type-2 like diabetes in leptin-resistant ratsBrain Res2007118416016717945204

- ArenasIATremblayJDeslauriersBDynamic genetic linkage of intermediate blood pressure phenotypes during postural adaptations in a founder populationPhysiol Genomics201345413815023269701

- LiangYOsborneMCMoniaBPAntisense oligonucleotides targeted against glucocorticoid receptor reduce hepatic glucose production and ameliorate hyperglycemia in diabetic miceMetabolism200554784885515988691

- SyedAAHalpinCGIrvingJAA common intron 2 polymorphism of the glucocorticoid receptor gene is associated with insulin resistance in menClin Endocrinol (Oxf)200868687988418194492

- TomlinsonJWStewartPMModulation of glucocorticoid action and the treatment of type-2 diabetesBest Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab200721460761918054738

- JääskelainenTMakkonenHPalvimoJJSteroid up-regulation of FKBP51 and its role in hormone signalingCurr Opin Pharmacol201111432633121531172

- LuFQianYLiHGenetic variants on chromosome 6p21.1 and 6p22.3 are associated with type 2 diabetes risk: a case-control study in Han ChineseJ Hum Genet201257532032522437209

- BouchardCPérusseLCurrent status of the human obesity gene mapObes Res19964181908787941

- ZintzarasEKitsiosGKentDGenome-wide scans meta-analysis for pulse pressureHypertension200750355756417635856

- DoyleAEBiedermanJFerreiraMAWongPSmollerJWFaraoneSVSuggestive linkage of the child behavior checklist juvenile bipolar disorder phenotype to 1p21, 6p21, and 8q21J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry201049437838720410730

- O’LearyJCZhangBKorenJBlairLDickeyCAThe Role of FKBP5 in Mood Disorders: Action of FKBP5 on Steroid Hormone Receptors Leads to Questions About its Evolutionary ImportanceCNS Neurol Disord Drug TargetsEpub 942013

- SeifuddinFPiroozniaMJudyJTGoesFSPotashJBZandiPPSystematic review of genome-wide gene expression studies of bipolar disorderBMC Psychiatry20131321323945090

- HorstmannSLucaeSMenkeAPolymorphisms in GRIK4, HTR2A, and FKBP5 show interactive effects in predicting remission to antidepressant treatmentNeuropsychopharmacology201035372774019924111

- SarginsonJELazzeroniLCRyanHSSchatzbergAFMurphyGMJrFKBP5 polymorphisms and antidepressant response in geriatric depressionAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2009153B255456019676097

- American Psychiatry AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th ed Text RevWashington, DC2000419422

- SchaidDJRowlandCMTinesDEJacobsonRMPolandGAScore tests for association between traits and haplotypes when linkage phase is ambiguousAm J Hum Genet200270242543411791212

- MartinMPGaoXLeeJHEpistatic interaction between KIR3DS1 and HLA-B delays the progression to AIDSNat Genet200231442943412134147

- GabuteroEMooreCMallalSStewartGWilliamsonPInteraction between allelic variation in IL12B and CCR5 affects the development of AIDS: IL12B/CCR5 interaction and HIV/AIDSAIDS2007211656917148969

- MilordEGragnoliCNEUROG3 variants and type 2 diabetes in ItaliansMinerva Med200697537337817146417