Abstract

Objective

We compared prophylactic effects of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) on upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) associated with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) and explored this influence on platelet function.

Methods

Randomized controlled trials and cohort studies comparing PPIs with H2RAs in adults receiving DAPT were collected from PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane databases. Dichotomous data were pooled to obtain risk ratios (RRs) for UGIB, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), poor responders to clopidogrel and rehospitalization, and continuous data were pooled to obtain mean differences (MDs) for P2Y12 reaction units (PRUs), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

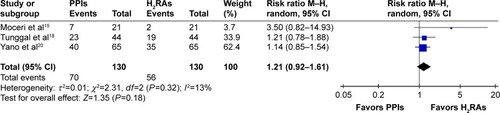

Twelve clinical trials (n=3,301) met the inclusion criteria. Compared to H2RAs, PPIs lessened UGIB (RR =0.16, 95% CI: 0.03–0.70), and there was no significant difference in the incidence of PRUs (MD =18.21 PRUs, 95% CI: −4.11–40.54), poor responders to clopidogrel (RR =1.21, 95% CI: 0.92–1.61), incidence of MACEs (RR =0.89, 95% CI: 0.45–1.75) or rehospitalization (RR =1.76, 95% CI: 0.79–3.92). Subgroup analysis confirmed fewer PRUs in the H2RAs group compared to the omeprazole group (2 studies, n=189, MD =31.80 PRUs, 95% CI: 11.65–51.96). However, poor responder data for clopidogrel and MACEs might be unreliable because few studies of this kind were included.

Conclusion

Limited evidence indicates that PPIs were better than H2RAs for prophylaxis of UGIB associated with DAPT and had no effect on platelet function. Further study is needed to confirm these observations.

Introduction

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT; clopidogrel and aspirin) is commonly used for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular (CV) and cerebrovascular diseases. DAPT can reduce the risk of subsequent stroke for a year after the first event.Citation1 In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), DAPT was confirmed to reduce the risk of stroke by 32% compared to aspirin alone in patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attacks.Citation2

As DAPT use increases, the incidence of DAPT-associated upper gastrointestinal (GI) injuries, including gastric mucosal erosions, peptic ulcers and bleeding, also rises. Morneau et al reported that DAPT therapy could increase twofold the risk of GI bleeding (GIB), especially in patients with multiple risk factors.Citation3 Thus, GIB prophylaxis was suggested for patients receiving DAPT therapy.

In 2007, the American College of Cardiology recommended antiulcer drugs for patients with a history of GIB, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) effectively lowered the adjusted risk of aspirin-induced GIB by 28%.Citation4 Meanwhile, histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) therapy can prevent ulcers for patients receiving low-dose aspirin.Citation5

Studies suggest that combination treatment with PPIs plus clopidogrel is associated with high platelet reactivity and more adverse events during long-term follow-up.Citation6,Citation7 PPIs were also shown to reduce responsiveness to standard clopidogrel doses and increased CV events for patients with the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C19 loss-of-function allele.Citation8 Moreover, H2RAs may be as effective as PPIs plus DAPT for patients with no prior history of upper GI bleeding (UGIB).Citation9 Therefore, H2RAs might be a reasonable alternative to PPIs, as they do not affect CYP 2C19 genotypes. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of PPIs compared with H2RAs for preventing UGIB associated with DAPT, and offered a foundation of evidence for clinical decision-making.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

We searched PubMed (January 1966 to August 2016), EMBASE (January 1974 to August 2016) and the Cochrane Collaboration’s Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2016 Issue 8) to identify clinical trials comparing the efficacy of PPIs to H2RAs for patients treated with DAPT consisting of aspirin and clopidogrel. The following search terms were used: aspirin, acetylsalicylic, clopidogrel, proton pump inhibitors, PPIs, esomeprazole, pantoprazole, omeprazole, rabeprazole, lansoprazole, histamine receptor blocker, H2 receptor antagonists, H2 blocker, H2RA, cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, roxatidine, nizatidine and lafutidine. Reference lists of original articles and reviews were manually searched for additional relevant studies. Experts in this field of study were consulted.

For this review, inclusion criteria included 1) RCTs (parallel or crossover design) and cohort studies; 2) patients treated with aspirin and clopidogrel; 3) PPIs versus H2RAs; 4) primary outcome of UGIB; secondary outcomes were P2Y12 reaction units (PRUs), number of poor responders to clopidogrel, major adverse CV events (MACEs) and rehospitalization frequency. All manuscripts were in English. UGIB referred to hematemesis, melena or a hemoglobin decrease of >2 g/dL, with or without endoscopy. Poor clopidogrel responder was defined by a PRU value >240 or a PRU% <20% or a platelet reactivity index >50%. MACEs referred to death from CV causes, spontaneous myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stent thrombosis, target vessel revascularization, nontarget vessel revascularization and ischemic stroke. The systematic review with meta-analysis was registered on PROSPERO (No CRD42015030158).

Study selection and quality assessment

Two authors (ZMY and TTQ) independently selected potentially eligible studies from the literature according to title and abstracts. Then, full-text versions were screened for potentially eligible studies to determine eligibility based on inclusion criteria.

Two authors (ZMY and TTQ) independently assessed the risk of bias in included studies. The methodological quality of eligible RCTs was evaluated with the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool,Citation10 in which critical quality assessments are made separately for different domains including method of randomization, concealment of allocation, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other biases. Considering that the observational studies were more vulnerable to the potential selection bias than RCTs, the methodological quality of eligible cohort studies was evaluated with the Newcastle–Ottawa scale.Citation11 Three domains including selection, comparability and outcome were assessed. All disagreements about study selection and quality assessment were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction was performed by each author (ZMY and TTQ) according to a predesigned review form, and study characteristics (author, publication year and type of study), participant characteristics (inclusion criteria, sample size, age and sex), intervention information (dosage, administration route and duration) and outcome measures (primary and secondary outcomes) were collected. All disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Meta-analyses were performed with RevMan 5.3. Dichotomous and continuous outcomes were expressed with random effect model as the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and mean difference (MD) with 95% CI, respectively. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed with the Mantel–Haenszel chi-square test and quantified using an I2 test (P-value of heterogeneity was 0.10). Subgroup analyses among different PPIs were conducted to explore sources of clinical heterogeneity in data regarding PRUs. According to the guidance in Chapter 16 of Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, when carryover or period effects were not serious for crossover studies, all measurements were analyzed as if the trials were parallel-group trials.Citation12 Sensitivity analysis was conducted by changing the random-effects methods to fixed-effects methods to pool the trials.

Results

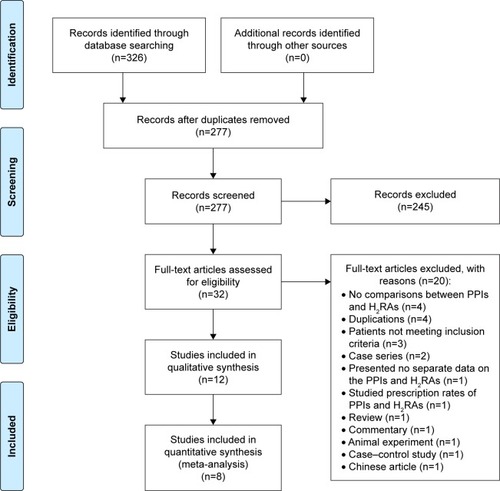

Search results and study characteristics

Studies identified are depicted in along with strategies for including relevant papers. Among studies that retrieved full text for inspection, 20 studies were excluded, and the details were as following: 4 had no comparisons between PPIs and H2RAs, 4 were duplications, patients did not meet inclusion criteria in 3 studies, 2 were case series, 1 presented no separate data on the PPIs and H2RAs, 1 studied prescription rates of PPIs and H2RAs, 1 was a review, 1 was a commentary, 1 was an animal experiment, 1 was a case–control study and 1 was a Chinese article with English abstract ().

Figure 1 Flow diagram for study selection.

depicts study characteristics, and bias risk data are shown in and . A total of 12 studies containing 3,301 patients (2,068 in the PPIs group, 1,233 in H2RAs group) were included in the analysis.Citation13–Citation24 The risk of bias for all included RCTs is high except the low risk of bias for Furtado et alCitation14 and moderate risk of bias for Ng et al.Citation16 For cohort studies, the risk of bias for Cappelletti Galante et al,Citation21 Ng et alCitation23 and Yew et alCitation24 is moderate and the risk of bias for Macaione et alCitation22 is high.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

Table 2 ROB of randomized controlled trials

Table 3 Risk of bias of cohort studies

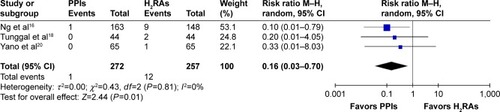

Incidence of UGIB

Three RCTsCitation16,Citation18,Citation20 reported the incidence of UGIB, and depicts the lack of heterogeneity between included trials and the pooled RR, confirming that PPIs decreased UGIB compared to H2RAs. Ng et al conducted a cohort study to measure UGIB events and treatment effect of PPIs and H2RAs, and the risk of UGIB was marginally reduced by H2RAs (odds ratio [OR] =0.43, 95% CI: 0.18–0.91), but significantly reduced by PPIs (OR =0.04, 95% CI: 0.002–0.21) compared to controls.Citation23

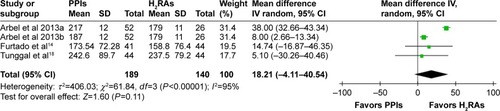

Antiplatelet effects

For antiplatelet effects, three outcomes were studied: PRUs, poor responders to clopidogrel (75 mg) and ADP-induced maximal amplitude (ADP-MA). Three RCTs reported the results of PRUs.Citation13,Citation14,Citation18 The washout period for the study by Arbel et alCitation13 was 2 weeks; blood samples were collected and results were analyzed in the manner of a parallel-group trial. Arbel et al’sCitation13 study data were divided into two groups of similar subject size; Arbel et al 2013a compared omeprazole and H2RAs and Arbel et al 2013b compared pantoprazole and H2RAs. Heterogeneity of included trials was significant, and there were no statistically significant differences among PRUs between the PPIs and H2RAs groups (). Subgroup analysis of the omeprazole group (n=163, 2 studies) indicated no significant heterogeneity between trials (P=0.16, I2=50%). At endpoint, the pooled MD of the subgroup was 31.82 PRUs (95% CI: 11.70–51.94), indicating that PRUs were fewer in the H2RAs group compared to the omeprazole group. The pantoprazole subgroup (1 study) had more PRUs compared to the H2RAs group (MD =8.00 PRUs, 95% CI: 2.66–13.34).

Figure 3 P2Y12 reaction units.

Moceri et al reported a decreased mean PRU% for those treated with esomeprazole compared to those treated with no drug (P<0.0001), but no statistical difference was found in the ranitidine group (P=0.97).Citation15

Three RCTsCitation15,Citation18,Citation20 reported of poor responders to clopidogrel (75 mg). The washout period in the study by Moceri et alCitation15 was 48 h, and blood samples were collected at the end of each phase. This washout period was sufficient to eliminate the effect of clopidogrel for poor responders and data were assessed as if this was a parallel-group trial. Heterogeneity of included trials was insignificant (see for data), and there were no statistically significant differences among numbers of poor responders to clopidogrel between the PPIs and H2RAs groups ().

Figure 4 Incidence of poor responders to clopidogrel.

Parri et al reported that pantoprazole plus DAPT significantly increased ADP-MA compared with ranitidine at 5 and 30 days’ follow-ups (P=0.01 and P=0.03, respectively), indicating that pantoprazole interfered with antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel.Citation17 Uotani et al conducted a three-way randomized crossover study including 20 Japanese subjects and reported that rabeprazole plus DAPT did not attenuate antiplatelet function compared with famotidine combined with DAPT.Citation19

Cardiovascular events

Two RCTs reported the incidence of MACEsCitation16,Citation20 and there was no heterogeneity between the trials (P=0.44, I2=0%) as well as no difference in the incidence of MACEs between PPIs and H2RAs therapy (RR =0.89, 95% CI 0.45–1.75). Yew et al published a retrospective cohort study in Singapore that included post-PCI patients who received either omeprazole or a H2RAs and DAPT and they confirmed that significantly more CV complications occurred in the omeprazole group (P=0.042).Citation24

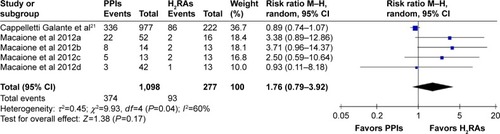

Rehospitalization

Two cohort studies reported the incidence of rehospitalization.Citation21,Citation22 Macaione et al’s study was divided into four groups () and each subgroup consisted of one-fourth of all patients. Macaione et alCitation22 2012a depicted omeprazole versus H2RAs; Macaione et al 2012b reported esomeprazole versus H2RAs; Macaione et al 2012c included results of lansoprazole versus H2RAs; and Macaione et al 2012d included results of pantoprazole versus H2RAs.Citation22 Heterogeneity of included trials was substantial and there were no statistically significant differences among incidence of rehospitalization between the PPIs and H2RAs groups ().

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

All pooled results were not affected by the different methods used. Due to a limited number of included studies for each outcome, we could not assess the risk of publication bias.

Discussion

This review compared the effectiveness and safety of PPIs to H2RAs for patients receiving DAPT, as assessed in RCTs and cohort studies. Limited evidence suggested that compared to H2RAs, PPIs decreased UGIB, and no differences were found in PRUs, poor responders to clopidogrel, or incidences of MACEs and rehospitalization. Among the PPIs, subgroup analyses suggested that omeprazole may increase PRUs.

A meta-analysis including ten RCTs by Mo et al showed that PPIs reduced LDA-associated UGIB.Citation25 Another meta-analysis of 39 studies by Cardoso et al indicated that PPIs decreased the risk of UGIB for patients taking clopidogrel and these data agreed with our results.Citation26 Only two trials were included in comparisons between PPIs and H2RAs by Mo et al,Citation25 and no comparisons of this nature were made by Cardoso et al.Citation26 Regarding CV events, Yasuda et al reported significantly more coronary stenotic lesions after treatment with PPIs compared with H2RAs,Citation27 whereas the CALIBER study confirmed that both PPIs and ranitidine were associated with higher incidence of death or myocardial infarctions.Citation28 A meta-analysis of RCTs and observational studies by Melloni et al had conflicting results regarding PPIsCitation29 and CV outcomes, and a systematic review by Focks et al challenged the validity of conclusions about PPI–clopidogrel interactions on platelet function and MACEs based on quantitative analyses of predominantly nonrandomized data.Citation30 A recent published RCT by Gargiulo et al also indicated that DAPT concomitant with PPIs did not increase death for myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident.Citation31 We found no difference in the incidence of MACEs and between PPIs and H2RAs. This suggested that the safety profile of PPIs were comparable with H2RAs. However, the small number of included studies might compromise the validity of this conclusion.

Patients with increased upper GI risk are more likely to receive PPIs and patients with increased CV risk are more likely to receive DAPT instead of aspirin or clopidogrel alone, and DAPT treatment is more likely to be paired with PPIs due to increased UGIB risk compared to aspirin or clopidogrel alone. Therefore, in cohort studies, imbalances in baseline characteristics and prescription bias may affect observed outcomes; patient prognostic factors at the RCT baseline may differ from a cohort study. Here, we noted conflicting results between RCTs and cohort studies for ADP-MA and MACEs and these results may be biased due to inherent difference in study characteristics (study designs, study population and different treatment durations from 7 days to 35 months). DAPT length may influence the bleeding risk; the PRODIGY study suggested an increase in bleeding risk without benefit from ischemic adverse events,Citation32 while benefit overcame the risk for some subgrousps at higher risk.Citation33 Thus, more studies are needed to draw firm conclusions.

Our report is the first of its kind to directly compare PPIs with H2RAs for prophylaxis and safety when used with DAPT and we included RCTs and cohort studies. A recent meta-analysis to compare the effects of concomitant use of PPIs and DAPT concluded that observational studies and RCTs have conflicting outcomes regarding PPIs on CV outcomes when coadministered with DAPT.Citation27 Thus, the results of both RCTs and cohort studies can decrease potential reporting bias. Subgroup analyses of four different types of PPIs to explore the potential effect differences indicate that omeprazole modified CYP 2C19 metabolism and reduced antiplatelet effects,Citation34 and this was consistent with our results. Since 2009, the US FDA recommended against concomitant use of clopidogrel and omeprazole and suggested, instead, the use of a weak CYP 2C19 inhibitor, pantoprazole.Citation35 However, in our study, two reports (one RCT and one cohort study) indicate that pantoprazole may have antiplatelet effects; so, we compared “poor responders to clopidogrel”, which was a more direct indicator of antiplatelet activity compared to PRUs.

Our study has some limitations. First, our topic has few reports in the literature and so clinical guidelines are similarly scarceCitation36 or unjustified based on current evidence.Citation37,Citation38 Thus, high-quality research is required to assess clinical practices and support guideline recommendations. Second, in this systematic review, we could not combine RCTs with observational studies due to lack of matching propensity scores or reporting adjusted RRs. Although 12 studies were included in the review, only 8 RCTs were included in our meta-analysis. Additionally, aggregate sample sizes of all included studies were small and this decreased precision of estimates. Subgroup analysis based on individual CYP 2C19 genotypes and Heliobacter pylori status could not be performed because few studies reported these data. Furthermore, only English-language studies were included and conference abstracts were not manually searched, although important conference abstracts were included in databases searched and included in our review.

Conclusion

The available evidence suggests that PPIs outperformed H2RAs for prophylaxis of UGIB associated with DAPT, and no differences in platelet function were observed. Likely, differences in antiplatelet activity are caused by omeprazole, but larger randomized controlled studies are required to compare PPIs with H2RAs for preventing UGIB during DAPT treatment.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by Award Number 2016B-YX007 from the Chinese Medical Association. We extend our special thanks to Hua Zhang from the Research Center of Clinical Epidemiology, Peking University Third Hospital for clarifying types of included studies. We thank Prof Shu-Sen Sun from the College of Pharmacy, Western New England University for editing assistance.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WangYPanYZhaoXCHANCE InvestigatorsClopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack (CHANCE) trial: one-year outcomesCirculation20151321404625957224

- WangXZhaoXJohnstonSCCHANCE investigatorsEffect of clopidogrel with aspirin on functional outcome in TIA or minor stroke: CHANCE substudyNeurology201585757357926283758

- MorneauKMReavesABMartinJBOliphantCSAnalysis of gastrointestinal prophylaxis in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrelJ Manag Care Pharm201420218719324456320

- Schjerning OlsenAMLindhardsenJGislasonGHImpact of proton pump inhibitor treatment on gastrointestinal bleeding associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use among post-myocardial infarction patients taking antithrombotics: nationwide studyBMJ2015351h509626481405

- HeYChanEWManKKDosage effects of histamine-2 receptor antagonist on the primary prophylaxis of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-associated peptic ulcers: a retrospective cohort studyDrug Saf201437971172125096957

- WeiszGSmilowitzNRKirtaneAJProton pump inhibitors, platelet reactivity, and cardiovascular outcomes after drug-eluting stents in clopidogrel-treated patients: the ADAPT-DES studyCirc Cardiovasc Interv2015810e00195226458411

- YamaneKKatoYTazakiJEffects of PPIs and an H2 blocker on the antiplatelet function of clopidogrel in Japanese patients under dual antiplatelet therapyJ Atheroscler Thromb201219655956922472213

- SimonNFinziJCaylaGMontalescotGColletJPHulotJSOmeprazole, pantoprazole, and CYP2C19 effects on clopidogrel pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships in stable coronary artery disease patientsEur J Clin Pharmacol20157191059106626071277

- YasuTSatoNKurokawaYSaitoSShojiMEfficacy of H2 receptor antagonists for prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding during dual-antiplatelet therapyInt J Clin Pharmacol Ther2013511185486024040853

- HigginsJPTGreenSChapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studiesHigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]The Cochrane Collaboration2011 Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.orgAccessed November 10, 2016

- WellsGASheaBO’ConnellDThe Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.aspAccessed November 10, 2016

- HigginsJPTDeeksJJAltmanDGChapter 16: Special topics in statisticsHigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]The Cochrane Collaboration2011 Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org

- ArbelYBiratiEYFinkelsteinAPlatelet inhibitory effect of clopidogrel in patients treated with omeprazole, pantoprazole, and famotidine: a prospective, randomized, crossover studyClin Cardiol201336634234623630016

- FurtadoRHGiuglianoRPStrunzCMDrug interaction between clopidogrel and ranitidine or omeprazole in stable coronary artery disease: a double-blind, double dummy, randomized studyAm J Cardiovasc Drugs201616427528427289472

- MoceriPDoyenDCerboniPFerrariEDoubling the dose of clopidogrel restores the loss of antiplatelet effect induced by esomeprazoleThromb Res2011128545846221777954

- NgFHTunggalPChuWMEsomeprazole compared with famotidine in the prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndrome or myocardial infarctionAm J Gastroenterol2012107338939622108447

- ParriMSGianettiJDushpanovaAPantoprazole significantly interferes with antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel: results of a pilot randomized trialInt J Cardiol201316752177218122727972

- TunggalPNgFHLamKFChanFKLauYKEffect of esomeprazole versus famotidine on platelet inhibition by clopidogrel: a double-blind, randomized trialAm Heart J2011162587087422093203

- UotaniTSugimotoMIchikawaHComparison of preventive effects of rabeprazole and famotidine on gastric mucosal injury induced by dual therapy with low-dose aspirin and clopidogrel in relation to CYP2C19 genotypes and H Pylori infectionGastroenterology20131445 Suppl 1S478S479

- YanoHTsukaharaKMoritaSInfluence of omeprazole and famotidine on the antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a prospective, randomized, multicenter studyCirc J201276112673268022864179

- Cappelletti GalanteMGarcia SantosVBezerra da CunhaGWAssessment of the use of clopidogrel associated with gastroprotective medications in outpatientsFarm Hosp201236421621922115860

- MacaioneFMontainaCEvolaSNovoGNovoSImpact of dual antiplatelet therapy with proton pump inhibitors on the outcome of patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing drug-eluting stent implantationISRN Cardiol2012201269276122792485

- NgFHLamKFWongSYUpper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with aspirin and clopidogrel co-therapyDigestion2008773–417317718577887

- YewMSYeoPSDOngJLPOmeprazole use is associated with increased cardiovascular complications in Asian patients on aspirin and clopidogrel after percutaneous coronary interventionJACC Cardiovasc Interv201472S17S18

- MoCSunGLuMLProton pump inhibitors in prevention of low-dose aspirin-associated upper gastrointestinal injuriesWorld J Gastroenterol201521175382539225954113

- CardosoRNBenjoAMDiNicolantonioJJIncidence of cardiovascular events and gastrointestinal bleeding in patients receiving clopidogrel with and without proton pump inhibitors: an updated meta-analysisOpen Heart201521e00024826196021

- YasudaHYamadaMSawadaSUpper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary stentingIntern Med200948191725173019797827

- DouglasIJEvansSJHingoraniADClopidogrel and interaction with proton pump inhibitors: comparison between cohort and within person study designsBMJ2012345e438822782731

- MelloniCWashamJBJonesWSConflicting results between randomized trials and observational studies on the impact of proton pump inhibitors on cardiovascular events when coadministered with dual antiplatelet therapy: systematic reviewCirc Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes201581475525587094

- FocksJJBrouwerMAvan OijenMGLanasABhattDLVerheugtFWConcomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors: impact on platelet function and clinical outcome- a systematic reviewHeart201399852052722851683

- GargiuloGCostaFAriottiSImpact of proton pump inhibitors on clinical outcomes in patients treated with a 6- or 24-month dual-antiplatelet therapy duration: Insights from the PROlonging Dual-antiplatelet treatment after Grading stent-induced Intimal hyperplasia studY trialAm Heart J20161749510226995375

- ValgimigliMCampoGMontiMProlonging Dual Antiplatelet Treatment After Grading Stent-Induced Intimal Hyperplasia Study (PRODIGY) InvestigatorsShort- versus long-term duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting: a randomized multicenter trialCirculation2012125162015202622438530

- CampoGTebaldiMVranckxPShort- versus long-term duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients treated for in-stent restenosis: a PRODIGY trial substudy (Prolonging Dual Antiplatelet Treatment After Grading Stent-Induced Intimal Hyperplasia)J Am Coll Cardiol201463650651224161321

- NorgardNBMathewsKDWallGCDrug-drug interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitorsAnn Pharmacother20094371266127419470853

- FoodUSAdministrationDrugFDA reminder to avoid concomitant use of Plavix (clopidogrel) and omeprazole Available from: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm231161.htmAccessed November 10, 2016

- BhattDLScheimanJAbrahamNSAmerican College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus DocumentsACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus DocumentsCirculation2008118181894190918836135

- AbrahamNSHlatkyMAAntmanEMACCF/ACG/AHAACCF/ACG/AHA 2010 expert consensus document on the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and thienopyridines: a focused update of the ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID useAm J Gastroenterol2010105122533254921131924

- TanHJMahadevaSMenonJStatements of the Malaysian Society of Gastroenterology & Hepatology and the National Heart Association of Malaysia task force 2012 working party on the use of antiplatelet therapy and proton pump inhibitors in the prevention of gastrointestinal bleedingJ Dig Dis201314111023134105