Abstract

Recovery after total hip arthroplasty (THA) is influenced by several psychological aspects, such as depression, anxiety, resilience, and personality traits. We hypothesized that preoperative depression impedes early functional outcome after THA (primary outcome measure). Additional objectives were perioperative changes in the psychological status and their influence on perioperative outcome. This observational study analyzed depression, anxiety, resilience, and personality traits in 50 patients after primary unilateral THA. Hip functionality was measured by means of the Harris Hip Score. Depression, state anxiety, and resilience were evaluated preoperatively as well as 1 and 5 weeks postoperatively. Trait anxiety and personality traits were measured once preoperatively. Patients with low depression and anxiety levels had significantly better outcomes with respect to early hip functionality. Resilience and personality traits did not relate to hip functionality. Depression and state anxiety levels significantly decreased within the 5-week stay in the acute and rehabilitation clinic, whereas resilience remained at the same level. Our study suggests that low depression and anxiety levels are positively related to early functionality after THA. Therefore, perioperative measurements of these factors seem to be useful to provide the best support for patients with risk factors.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis is a degenerative joint disease that may affect every joint of the body. Hips and knees, in particular, are often affected, and hip osteoarthritis is one of the most common types of osteoarthritis.Citation1 If conservative treatment options are exhausted, joint replacement surgery is a widely accepted, effective treatment option for end-stage osteoarthritis.Citation2 Although joint replacement surgery is the most successful orthopedic surgical intervention, not every patient is completely satisfied after surgery.Citation3–Citation6 Therefore, over the past few years, interest has been focused on the influence of psychological factors on outcome after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA). Vissers et alCitation7 conducted a systematic review of what psychological factors influence the outcome after THA or TKA and to what extent. They found that pain catastrophizing and impaired mental health before TKA were associated with lower scores for function and higher scores for postoperative pain. Moreover, their results indicated that preoperative depression does not influence postoperative functioning. Another finding of their study was that only a few studies on psychological factors after THA are available so far, and that these studies have yielded limited or conflicting results.Citation6,Citation8–Citation13

Our study concentrated on the influence of psychological factors on the outcome after THA. We focused on psychological factors such as major depression, state and trait anxiety, resilience, and personality traits that play an important role in today’s medicine according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Burden of Disease Study.Citation14 The prevalence of these factors is likely to increase in the coming years. A large study, including more than 200,000 participants in 60 countries, investigated combinations of diseases. Depression was found to have the most negative influence on health in combination with other diseases, such as angina, arthritis, asthma, or diabetes.Citation15 Several studies have evaluated psychological aspects in orthopedics, eg, the effect of depression on the occurrence of femoral neck fractures and distal radius fractures.Citation16–Citation18 A research group from Italy has reported about the positive influence of psychological support of patients undergoing THA or TKA. Regarding the hip arthroplasty group, patients receiving psychological support reached the physiotherapeutic objective 1.2 days earlier than patients without any such support.Citation19 Other studies have dealt with the aspects of fear and pain in correlation with THA and TKA surgeryCitation20 or depression and anxiety as a predictor for complications.Citation21 Buller et alCitation22 have recently reported on the influence of psychiatric comorbidity (eg, depression, anxiety, dementia, and schizophrenia) on perioperative outcome after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Diagnosis of depression, dementia, and schizophrenia was associated with increased odds of adverse events.Citation22 Overall, only a few studies have yet evaluated the influence of a variety of psychological dispositions on outcome after orthopedic surgery. According to the literature reports, we expected a relationship between depression and THA outcome measured with the Harris Hip Score (HHS), whereas a possible relationship between resilience, anxiety, and different personality traits remains to be investigated. Therefore, the main goal of our study was to investigate the relationship between depression, resilience, state and trait anxiety, and different personality traits and the healing process and early functional outcome measured by means of the HHS.

Methods

Participants

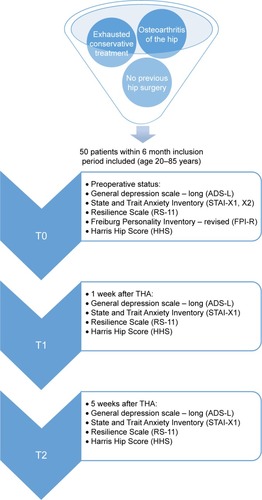

This prospective study included 50 patients who underwent total hip replacement in a center of excellence for arthroplasty. The inclusion period was 6 months, and inclusion criteria were 1) osteoarthritis of the hip; 2) exhausted conservative treatment; 3) age between 20 and 85 years; and 4) no previous hip surgery. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the University of Regensburg (2009-09/136) and carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. Written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects. The study has been registered in the DRKS (Deutsches Register Klinischer Studien, German Clinical Trials Register, WHO register) with the DRKS00010536.

Procedure

The same group of senior surgeons conducted all surgical interventions as a consecutive series. Patients remained at the acute clinic for about 8 days followed by a 4-week stay at the rehabilitation center of the same hospital.

Depression, anxiety, resilience, Freiburg Personality Inventory

The level of depression was measured by means of the “Allgemeine Depressionsskala” (general depression scale – long, ADS-L), which is the German version of the CES-D-Scale (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale).Citation23–Citation26

Anxiety was determined with the “State and Trait Anxiety Inventory” (STAI).Citation27,Citation28 Spielberger described state anxiety as “existing in a transitory emotional state”, which varies in intensity and fluctuates over time, whereas trait anxiety refers to stable susceptibility or proneness to frequent experiences of state anxiety.Citation27,Citation28 STAI-X1 measures the state anxiety at the present time, which can be induced temporarily by different situations. The STAI-X2 measurement can be described as a relative stable disposition for anxiety that does not depend on a specific situation.

Resilience levels were measured with the “Resilience Scale” (RS-11) developed by Wagnild and Young.Citation29 The authors equated “resilience” with emotional stamina, and this term has been used to describe people displaying courage and adaptability in the wake of life’s misfortunes. Luthar et alCitation30 used the term “resilience” for describing a person’s capability to positively adapt to adverse conditions.

For the different personality traits, we used the Freiburg Personality Inventory – revised (FPI-R), which is a psychological test to assess personality.Citation31 The application is focused, among others, on the area of rehabilitation. Twelve personality characteristics are assessed by means of 138 items of the FPI-R questionnaire: life satisfaction (LIF), social orientation (SOC), achievement orientation (ACH), inhibitedness (INH), impulsiveness (IMP), aggressiveness (AGG), strain (STR), somatic complaints (SOM), health concern (HEA), frankness (FRA), and two secondary factors (following Eysenck), namely, extra-version (EXT) and emotionality (neuroticism) (EMO).

Function

The HHS was used to assess the clinical health status relevant to THA outcome.Citation32 This score includes a rating scale of 100 points for the domains pain, function, activity, deformity, and motion. The HHS was first published in 1969 and has been established as a valid and reliable index to assess the results of hip replacement surgery.Citation33–Citation37

Schedule

Prior to surgery (T0), the psychological profile and hip status of each patient were established by evaluating the ADS-L, STAI-X1 and -X2, RS-11, FPI-R, and HHS. The ADS-L, STAI-X1, RS-11, and HHS were evaluated once again 1 week after surgery (T1), which was equivalent to the end of the stay at the acute clinic. The same procedure was conducted 5 weeks after THA (T2) in the rehabilitation center, in which all patients underwent the same rehabilitation program (). At admission to hospital, all eligible patients were asked to participate. To determine the factors to be investigated and minimize the risks of exogenous influence in the home environment, we chose a 5-week follow-up period, which means that patients were seen after their stay in the acute clinic and rehabilitation center.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis consisted of both descriptive and inferential measures. Mean values and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated for continuous variables. After collecting the data, we divided the results of each psychological factor at T0 into two groups: Group 1 (≥ median) and Group 2 (< median). The HHS was the dependent variable. The significance level was established at 0.05. Furthermore, statistical significance for outcomes of interest was determined by means of multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). MANOVA was used because the HHS was registered at three different times, resulting in three different dependent variables. We decided to use the MANOVA, because a high correlation between the results of the HHS on the three measurement times could be assumed. For correlation analyses, Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was used. All statistical analyses were done using Predictive Analytics Software 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The analyzed cohort contained 27 women and 23 men. The mean age was 62.18 years (SD =11.48), body height was 5.54 feet (SD =0.27), and body mass index 27.95 (SD =5.44) (). Twenty-seven patients received surgery at the right hip, and 23 patients at the left hip. Sixty-one patients were eligible for inclusion. Seven patients declined to participate, and in two patients, the operation had to be canceled because of increased inflammation parameters. Two patients withdrew their consent without any reason.

Table 1 Demographic data of the included patients

Change of psychological factors (descriptive data)

The ADS-L (the general depression scale) increased from 16.8±8.8 (T0) to 17.6±9.3 (T1) and then decreased to 11.9±6.2 (T2) (). State anxiety (X1) started at 44.1±12.3, decreased continuously to 38.9±11.0, and finally dropped to 35.1±10.2.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics at T0, T1, and T2, (N=50)

Trait anxiety was expected to be a continuous parameter and was therefore assessed just once, yielding a value of 38.7±9.9. RS-11 results confirmed the expectation of resilience to also be a continuous parameter. The mean value was constant at 59.9±11.0, 59.3±11.1, and 59.7±11.0. The results of FPI-R are shown in .

Table 3 Results of the FPI-R (N=50)

The HHS indicated improved early outcome after surgery. The preoperative result was 49.6±19.8, the result at T1 was 60.0±13.9 and 73.3±8.8 at T2.

Independent psychological factors for hip functionality

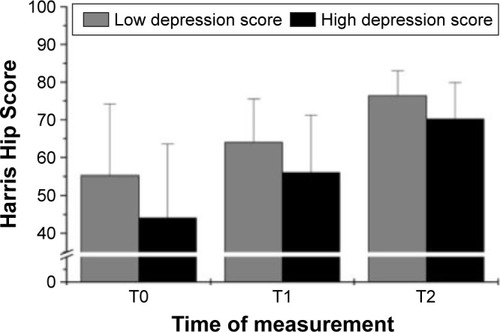

Depression score and HHS

The results showed that the degree of depression is related to the HHS outcome at every point in time (T0: F(1.48) =6.146, P=0.017, η2=0.114; T1: F(1.48) =6.570, P=0.014, η2=0.120; and T2: F(1.48) =7.017, P=0.011, η2=0.128). Patients with a lower degree of depression showed better hip functionality at every measurement ().

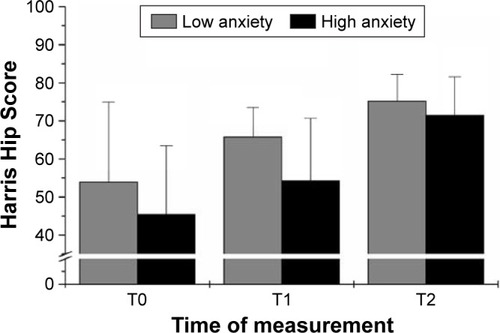

Anxiety and HHS

The only significant effect of anxiety occurred 1 week after surgery and concerned trait anxiety (T1: F(1.48) =9.900, P=0.003, η2=0.171; ).

Resilience, personality traits, and HHS

Resilience was not related to HHS outcome. After alpha-adjusting the correlations between FPI-scores and HHS calculated for every point in time, the only significant correlation was between somatic pain and HHS at T1 (r=−0.451, P=0.001).

Discussion

The objective of our study was to examine various psychological variables potentially addressing outcome. The influence of psychological factors on outcome after surgery is undisputed. However, psychological factors are not routinely assessed before surgery.Citation38 Furthermore, the most suitable yellow flag assessment tool for identifying psychological risk factors is still unclear. Establishing biopsychosocial models requires an understanding of what psychological factors mainly influence THA outcome.

Our study showed significant changes in depression and anxiety scores over the investigated period. Moreover, we found a significant relationship of depression and anxiety with hip functionality. The plausibility of our findings was shown by comparing our HHS results with those of another study, performed in our hospital earlier by Sendtner et al.Citation39 The preoperative mean in Sendtner’s study was 49.66 points, which was like our results. This score means that patients in both studies had “poor hip functionality”. After 1 year, both HHS values in Sendtner’s study rose to 92 points. Five weeks after surgery, our patients reached 73.28 points, which was a lower score than that of Sendtner’s patients. However, this score seems comprehensible in view of the shorter postoperative period in our study.

Primary outcome measure: depression as an influence factor

Not only the psychological scores but also other experiments showed similar results. For instance, the ADS-L as a German version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used in a follow-up study on patients with fractures of the femoral neck. According to this study, 51% of participants had elevated CES-D levels after surgery. The 1-year follow-up showed a correlation between high CES-D levels and poor hip functionality.Citation16 Our investigation showed similar results. Initially, the mean rose from 16.80±8.75 to 17.58±9.34. Badura-Brzoza et alCitation10 used a similar study design, measuring depression and its effects on THA outcome. They found higher preoperative depression levels that decreased after THA (P=0.003). However, no effect on outcome could be shown. In contrast, Riediger et alCitation13 showed a correlation between high depression levels and poor outcome. Depressive patients had a lower median WOMAC (Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) sum score of 30 (versus 45) preoperatively and 72 (versus 85) postoperatively. Gold et alCitation40 found depression to be associated with a significantly higher risk of readmission after THA. Our findings showed depression to be related to outcome at every measurement after THA, 1 week after surgery as well as after the 5-week postoperative phase.

Anxiety as an influence factor

The STAI score was used to show the impact of anxiety on pain after THA and TKA.Citation20 The study claimed state anxiety to be the only predictor for pain. Since pain is an important factor in the HHS (44 points in total), this comparison is very interesting. Our findings only showed an effect of trait anxiety 1 week after surgery. Montin et alCitation9 explored the effect of anxiety after THA not in view of physical healing but in the context of psychological recovery with a focus on quality of life.Citation8 STAI was also used in that investigation. Although no correlation was shown, their scientific research question was less interesting for our study than their concrete STAI results: the design of their experiment was similar to ours, with an initial preoperative value and follow-up measurements after 1 month. When preoperatively investigating 100 patients, Montin et alCitation9 found a mean value of 44.5 (SD =4.5) at X1 and 42.8 (SD =4.9) at X2. At the same point of time, our patients had 44.06 (SD =12.3) at X1 and 38.7 (SD =9.9) at X2. One month after surgery, Montin et alCitation9 measured 44.8 (SD =3.7) for state anxiety in contrast to 35.12 (SD =10.2) in our patients. Montin et alCitation9 initially also measured trait anxiety only once. The comparison shows that their study design and methods were similar to our investigation, but also that we had almost identical preoperative values for state anxiety. From our point of view, it is surprising that the participants in Montin’s study showed almost no change in state anxiety values. Even the values measured at the 6-month follow-up remained more or less the same, whereas our patients showed significantly improved values (P≤0.001). From our perspective, this improvement corresponds with the situational character of state anxiety in a better way and seems therefore very plausible when taking the entire process into consideration. Badura-Brzoza et alCitation10 also measured trait anxiety only once, yielding an arithmetic mean of 46.5 points. State anxiety was preoperatively calculated with 47.9 points and postoperatively with 41.1 points, which also supported our findings. Although the anxiety levels found by Badura-Brzoza et alCitation10 were only slightly higher, the authors considered trait anxiety as the most important factor for quality of life. Despite the lack of exact matches between the cited studies and our results, there is a strong indication that changes in anxiety over the course of surgical treatment play an important role in outcome. Even though the cited studies focused on quality of life after surgery, our study showed similar results for hip functionality after THA.

Resilience and personality traits as outcome predictors

Besides depression and anxiety, we also measured patient resilience using the RS-11. Although several studies have focused on resilience, we could not find any study examining the influence of resilience on hip functionality after THA.Citation41,Citation42 Resilience did not change over the course of our study.

A comprehensive psychological view of our patients was obtained by using the FPI-R. The FPI-R is a long-term validated score that has been used in many different experiments on widely varying issues, even on orthopedics.Citation43,Citation44 One study showed that neuroticism is associated with mental (P=0.03) and physical (P=0.005) performance after THA.Citation10 We could only find a significant correlation between somatic pain and HHS at 1 week after surgery.

In summary, our results confirmed that somatic variables are not the only ones responsible for pain and dysfunctionality after THA. Depression and trait anxiety seem to be the most important and reliable predictors for identifying psychological risk factors influencing outcome after THA. The results of this study may provide useful advice for supporting measures around the time of hip surgery in elderly people.

Limitations

Our study had some limitations. First, our study cohort was rather small because it included only patients staying at the clinic and the integrated rehabilitation center for 6 weeks. Although the follow-up period seems to be short, in choosing this period we wanted to minimize the risks of exogenous influence in the home environment. It remains unclear whether our results can be transferred to patients staying less than 6 weeks. Another limitation is that there is no blinding of researchers or participants, and as in all studies using scores, the truthfulness of patients’ answers cannot be verified. The participants were included just one after the other by meeting the inclusion criteria, which can be a kind of selection bias.

Conclusion

Several studies have acknowledged the crucial role of psychological factors in the context of pain and disability associated with osteoarthritis. Only a few publications have considered psychological factors when examining outcome after joint replacement surgery. Our findings show that THA is a very stressful situation for patients with enormous changes in depression and anxiety levels. Every fifth patient had critical depression values, and more than two-thirds of our study participants had abnormal anxiety levels. Our results showed a significant negative relationship, particularly of high-level depression on hip functionality after THA. Of course, this study represents only one method of investigating the effects of psychological factors on outcome after THA. Vissers et alCitation7 claimed that relatively few studies evaluated the effects of psychological factors on outcome after THA. Our study gives the first comprehensive picture of different psychological factors relating to the short-term outcome after hip surgery. The results of the present study emphasize the important role of psychological factors on outcome after surgery. Screening procedures could identify high-risk patients and ensure an integrated therapy. Therefore, further studies are required to develop a more evidence-based therapeutic procedure, to investigate the effect of depression on long-term outcome, and to investigate whether preoperative treatment of depression may improve outcome after THA.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Monika Schöll for the linguistic review of their manuscript. This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) within the funding program, Open Access Publishing.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KimCLinsenmeyerKDVladSCPrevalence of radiographic and symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in an urban United States community: the Framingham osteoarthritis studyArthritis Rheumatol201466113013301725103598

- JonssonHOlafsdottirSSigurdardottirSIncidence and prevalence of total joint replacements due to osteoarthritis in the elderly: risk factors and factors associated with late life prevalence in the AGES-Reykjavik StudyBMC Musculoskelet Disord2016171426759053

- KayADavisonBBadleyEWagstaffSHip arthroplasty: patient satisfactionBr J Rheumatol1983222432496652388

- ShanLShanBGrahamDSaxenaATotal hip replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis on mid-term quality of lifeOsteoarthritis Cartilage20142238940624389057

- MancusoCASalvatiEAPatients’ satisfaction with the process of total hip arthroplastyJ Healthc Qual2003251218 quiz 18–19

- AnakweREJenkinsPJMoranMPredicting dissatisfaction after total hip arthroplasty: a study of 850 patientsJ Arthroplasty20112620921320462736

- VissersMMBussmannJBVerhaarJAPsychological factors affecting the outcome of total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic reviewSemin Arthritis Rheum20124157658822035624

- SalmonPHallGMPeerbhoyDInfluence of the emotional response to surgery on functional recovery during 6 months after hip arthroplastyJ Behav Med20012448950211702361

- MontinLLeino-KilpiHKatajistoJLepistöJKettunenJSuominenTAnxiety and health-related quality of life of patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritisChronic Illn2007321922718083678

- Badura-BrzozaKZajacPBrzozaZPsychological and psychiatric factors related to health-related quality of life after total hip replacement – preliminary reportEur Psychiatry20092411912418835521

- Badura-BrzozaKZajacPKasperska-ZajacAAnxiety and depression and their influence on the quality of life after total hip replacement: preliminary reportInt J Psychiatry Clin Pract20081228028424937714

- QuintanaJMEscobarAAguirreULafuenteIArenazaJCPredictors of health-related quality-of-life change after total hip arthroplastyClin Orthop Relat Res20094672886289419412646

- RiedigerWDoeringSKrismerMDepression and somatisation influence the outcome of total hip replacementInt Orthop201034131819034446

- WhitefordHAFerrariAJDegenhardtLFeiginVVosTThe global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: an analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010PLoS One201510e011682025658103

- MoussaviSChatterjiSVerdesETandonAPatelVUstunBDepression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health SurveysLancet200737085185817826170

- MosseyJMKnottKCraikRThe effects of persistent depressive symptoms on hip fracture recoveryJ Gerontol199045M163M1682394912

- FortinskyRHBohannonRWLittMDRehabilitation therapy self-efficacy and functional recovery after hip fractureInt J Rehabil Res20022524124612352179

- GongHSLeeJOHuhJKOhJHKimSHBaekGHComparison of depressive symptoms during the early recovery period in patients with a distal radius fracture treated by volar plating and cast immobilisationInjury2011421266127021310409

- TristainoVLantieriFTornagoSGramazioMCarriereECameraAEffectiveness of psychological support in patients undergoing primary total hip or knee arthroplasty: a controlled cohort studyJ Orthop Traumatol20161713714726220315

- FeeneySLThe relationship between pain and negative affect in older adults: anxiety as a predictor of painJ Anxiety Disord20041873374415474849

- RasouliMRMenendezMESayadipourAPurtillJJParviziJDirect cost and complications associated with total joint arthroplasty in patients with preoperative anxiety and depressionJ Arthroplasty20163153353626481408

- BullerLTBestMJKlikaAKBarsoumWKThe influence of psychiatric comorbidity on perioperative outcomes following primary total hip and knee arthroplasty; a 17-year analysis of the National Hospital Discharge Survey databaseJ Arthroplasty20153016517025267536

- MeyerTDHautzingerMPrediction of personality disorder traits by psychosis proneness scales in a German sample of young adultsJ Clin Psychol2002581091110112209867

- HammerEMHäckerSHautzingerMMeyerTDKüblerAValidity of the ALS-Depression-Inventory (ADI-12) – a new screening instrument for depressive disorders in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Affect Disord200810921321918262283

- ReimeBSteinerIBurned-out or depressive? An empirical study regarding the construct validity of burnout in contrast to depressionPsychother Psychosom Med Psychol20015130430711536072

- MeyerTDHautzingerMAllgemeine Depressions-Skala (ADS)Diagnostica200147208215

- PaulsCAStemmlerGRepressive and defensive coping during fear and angerEmotion2003328430214498797

- SpielbergerCDState-Trait Anxiety Inventory: Bibliography2nd edPalo Alto, CAConsulting Psychologists Press1989

- WagnildGMYoungHMDevelopment and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience ScaleJ Nurs Meas199311651787850498

- LutharSSCicchettiDBeckerBThe construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future workChild Dev20007154356210953923

- FahrenbergJHampelRSelgHFreiburger Persönlichkeitsinventar (FPI-R). erweiterte Auflage. ManualGoettingen, GermanyHogrefe2010

- HarrisWHTraumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluationJ Bone Joint Surg Am19695147377555783851

- SinghJASchleckCHarmsenSLewallenDClinically important improvement thresholds for Harris Hip Score and its ability to predict revision risk after primary total hip arthroplastyBMC Musculoskelet Disord20161725627286675

- SödermanPMalchauHHerbertsPOutcome of total hip replacement: a comparison of different measurement methodsClin Orthop Relat Res2001390163172

- SödermanPMalchauHIs the Harris hip score system useful to study the outcome of total hip replacement?Clin Orthop Relat Res200138418919711249165

- KavanaghBFFitzgeraldRHJrClinical and roentgenographic assessment of total hip arthroplasty. A new hip scoreClin Orthop Relat Res19851931331403971612

- WrightJGYoungNLA comparison of different indices of responsivenessJ Clin Epidemiol1997502392469120522

- LentzTABeneciukJMBialoskyJEDevelopment of a yellow flag assessment tool for orthopaedic physical therapists: results from the Optimal Screening for Prediction of Referral and Outcome (OSPRO) CohortJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther20164632734326999408

- SendtnerEBorowiakKSchusterTWoernerMGrifkaJRenkawitzTTackling the learning curve: comparison between the anterior, minimally invasive (Micro-hip®) and the lateral, transgluteal (Bauer) approach for primary total hip replacementArch Orthop Trauma Surg201113159760220721570

- GoldHTSloverJDJooLBoscoJIorioROhCAssociation of depression with 90-day hospital readmission after total joint arthroplastyJ Arthroplasty2016312385238827211986

- CatalanoDChanFWilsonLChiuCYMullerVRThe buffering effect of resilience on depression among individuals with spinal cord injury: a structural equation modelRehabil Psychol20115620021121843016

- Ramírez-MaestreCEsteveRLópezAEThe path to capacity: resilience and spinal chronic painSpine (Phila Pa 1976)201237E251E25821857397

- RadlRLeithnerAZacherlMLacknerUEggerJWindhagerRThe influence of personality traits on the subjective outcome of operative hallux valgus correctionInt Orthop20042830330615241625

- HärtlKEngelJHerschbachPReineckerHSommerHFrieseKPersonality traits and psychosocial stress: quality of life over 2 years following breast cancer diagnosis and psychological impact factorsPsychooncology20101916016919189279