Abstract

Background

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are acute life-threatening adverse drug reactions (ADRs) that are commonly caused by medications. Apart from their contribution to morbidity and mortality, these diseases may also present substantial consequences on health care resources. In this study, we aimed to identify the incidence, causative drugs, and economic consequences of these serious ADRs and potential drug–drug interactions (DDIs) during treatment.

Methods

A retrospective study that included 150 patients diagnosed with drug-induced SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN, from 2009 to 2013 in a referral hospital in West Java Province, Indonesia, was conducted to analyze the causative drugs, cost of illness (COI) as a representation of economic consequences, and potential DDIs during treatment.

Results

The results showed that analgesic–antipyretic drugs were the most frequently implicated drugs. The COIs for SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN patients were 119.49, 139.21, and 162.08 US dollars per day, respectively. Furthermore, potential DDIs with several therapeutic medications and corticosteroids used to treat SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN were also identified.

Conclusion

This study showed that analgesic–antipyretic was the major causative drug which contributed to SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN. Furthermore, our results also showed that SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN may cause considerable financial consequences to patients.

Introduction

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are acute life-threatening adverse drug reactions (ADRs) characterized by epidermal detachment and mucositis.Citation1 The basic difference between SJS and TEN is the percentage of body surface affected, and SJS affects <10% of the body surface, SJS–TEN overlap involves 10%–30% of the body surface, and TEN affects >30% of the body surface area.Citation2,Citation3 The incidence varies from 1 to 6 cases and 0.4 to 1.2 cases per million annually for SJS and TEN, respectively.Citation4–Citation6 However, the incidence is higher among people living with HIV/AIDS.Citation7

Drugs are identified as the main etiologic agents of SJS, TEN, and SJS–TEN overlap syndrome. Based on RegisSCAR/EuroSCAR registries, the highest risk drugs include allopurinol, carbamazepine, cotrimoxazole, and other anti-infective sulfonamides, sulfasalazine, lamotrigine, nevirapine, oxicam-type non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), phenobarbital, and phenytoin. Moderate-risk drugs include cephalosporins, macrolides, quinolones, tetracyclines, and acetic acid-type NSAIDs. Low-risk drugs, that in previous studies, were not associated with a measurable risk, including beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, sulfonamide-based thiazide diuretics, sulfonylurea anti-diabetics, insulin, and propionic acid–type NSAIDs.Citation8,Citation9

Despite the fact that the incidence of SJS or TEN is acute life-threatening, the condition may also lead to significant financial consequences for the patients.Citation10 Therefore, identification and withdrawal of drugs suspected to cause SJS or TEN are important.Citation11 In Indonesia, however, little work has been conducted to identify the prevalence, causative drugs, and economic consequences caused. Accordingly, it is important to explore the best strategy to find as many relevant studies as possible. Thus, this study was aimed to identify the number of incidence, causative drugs, economic consequences, and potential drug–drug interaction (DDI) during treatment of these serious ADRs.

Methods

Data collection and study populations

We conducted a retrospective study in a referral hospital in West Java Province, the most populous Indonesian province, that is covered with 46.7 million population.Citation12 Medical records from patients diagnosed with drug-induced SJS (ICD10 code L50.1), TEN (L50.2), or SJS–TEN overlap (L50.3) syndrome from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2013, were recalled and included in the study. A data collection sheet was designed for the purpose of organizing collected data from patient records. Data included patient demographics, disease progression, duration of hospital stay, detailed treatment regimen, and suspected causative drugs as specifically mentioned in medical records by treating physicians. Incomplete patient records and records of patients referred with SJS, TEN, or SJS–TEN overlap syndrome from other hospitals were excluded from the study. Incomplete patient records that excluded were due to insufficient data and improper record, that is missing of suspected causative drug from the treating physicians, and incomplete medical treatment records. Two authors (RA and DPD) independently assessed the medical record for inclusion to the study. Differences were discussed and consensus reached.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Committee for Health Research of Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia No: LB.04.01/A05/EC/536/XII/2014. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was not required because this was a retrospective observational study. No medical interventions were performed during the study. All ethical considerations were followed. Patient files were processed anonymously. No personal data were collected.

Analysis of economic consequences

The economic consequences of SJS, TEN, and SJS–TEN overlap were calculated using cost of illness (COI) for each patient. A societal perspective was applied in this study by considering the total direct medical cost and indirect cost of lost productivity. The direct medical cost was calculated by considering the price of all medications received, expenses (preparation and administrative costs, monitoring costs, and the costs of treatment for adverse events and treatment failures), the cost of action, and the hospital room rate (including fees for doctors, nurses, pharmacies, and nutritionists that differ depending on the severity and treatment received by each patient). The potential loss of productivity was calculated using a report from the Indonesian Statistical Agency for average monthly income of people living in Bandung City, Indonesia,Citation13 that adjusted to the total length of hospital stay of each patient.

Currency was converted from the Indonesian rupiah (IDR) to the US dollar (USD) using the World Bank’s purchasing power parity (PPP) conversion factor, which is the number of units of a country’s currency required to buy the same amount of goods and services in the domestic market as the USD would buy in the USA.Citation14

Analysis of drug interaction

The analysis of potential DDIs was performed to analyze the interactions of SJS/TEN treatment with the drugs suspected of being the cause of SJS/TEN and interactions of concomitant therapy between SJS/TEN treatment with drugs used to treat the original disease not related to SJS/TEN. Identification of DDIs was performed with Truven Health Analytics Micromedex®, a registered subscription database, and Drugs.com™ and Medscape.com™, 2 free databases. Micromedex provides reference information for drug management for diseases and conditions, as well as toxicology and patient education. Micromedex identifies potential DDIs, including the mechanism of DDIs, potential adverse reactions, their clinical consequences, and level of documentation available for the interaction (excellent: controlled study have clearly established; good: documentation strongly suggests the interactions; fair: available documentations were poor).Citation15 Drugs.com is a free database powered by Wolters Kluwer Health, the American Society of HealthSystem Pharmacists, Cerner Multum, and Micromedex, which are leading medical information databases.Citation15 Medscape.com provides online medical information and educational tools,Citation16 including a drug interaction checker.

Results

Number of incidence

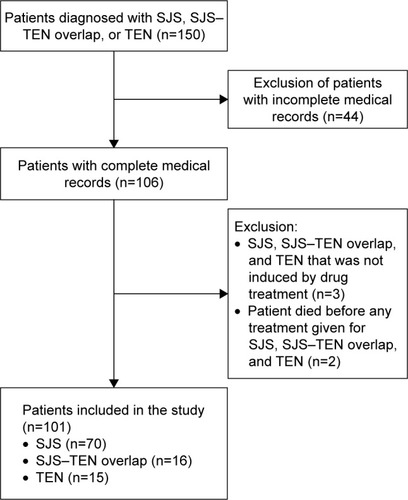

From the records of 150 patients diagnosed with SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN during 2009–2013, a total of 101 medical records were included in this study. The details of the selection process are shown in . The demographics of the patients included in this study are shown in .

Figure 1 Detailed medical record selection process.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of patients included in this study

Economic consequences

The total economic loss from the 101 cases of SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN during the study period was estimated at 131,763.82 USD, including 77,786.64, 29,179.29, and 24,797.89 USD from SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN, respectively. For SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN, the average cost per patient was 1,111.24, 1,823.71, and 1,653.12 USD, respectively, and the average direct cost per patient was 974.86, 1,630.91, and 1,504.07 USD, respectively. A detailed breakdown of the cost calculation and average spending per patient per day for SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN can be seen in .

Table 2 Economic cost calculation and average spending per patient per day for each case of SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN in this study

Causative drugs

Each drug implicated in SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN in the study can be seen in . As shown, analgesic–antipyretic drugs (acetaminophen) were reported most frequently, followed by antibiotics (amoxicillin, cotrimoxazol, and ciprofloxacin), tuberculosis drugs (rifampicin, ethambutol, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide), anti-HIV medications (nevirapine, lamivudine, and zidovudine), and NSAIDs (mefenamic acid, ibuprofen, and aspirin). In , the implicated drugs were compared to other reports from Japan,Citation17 Europe and Israel,Citation18 France,Citation19 sub-Saharan Africa,Citation20 and Senegal.Citation21

Table 3 Drugs implicated in SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN, their incidence in this study, and comparison with other reports

Potential DDIs

The results of DDI analysis from 3 of the databases showed discrepancies in the classification of severity and mechanism of interaction (). However, we found 29 cases identified by all 3 databases for potential interactions of SJS/TEN treatment with the drugs suspected of being the cause of SJS/TEN and 87 cases identified by all 3 databases for potential interaction of concomitant therapy between SJS/TEN treatment with drugs used to treat the original disease not related to SJS/TEN. The most common potential DDIs of corticosteroids with the drugs suspected of being the cause of SJS/TEN identified by the 3 databases were dexamethasone–rifampicin (24.14%), dexamethasone–ciprofloxacin (20.69%), dexamethasone–ibuprofen (20.69%), dexamethasone–mefenamic acid (17.24%), and dexamethasone–aspirin (10.34%). Meanwhile, the most common potential DDIs of concomitant treatment of corticosteroids with drugs used to treat the original disease not related to SJS/TEN were dexamethasone–ofloxacin (12.64%), dexamethasone–levofloxacin (10.34%), dexamethasone–ciprofloxacin (8.05%), dexamethasone–efavirenz (6.90%), and dexamethasone–phenobarbital (6.90%).

Table 4 Results of DDI analysis of (A) corticosteroids with the drugs suspected of being the cause of SJS/TEN and (B) concomitant treatment of corticosteroids with drugs used to treat the original disease not related to SJS/TEN, identified using the Micromedex, Drugs.com, and Medscape.com websites

Discussion

The drugs most frequently implicated in cases of SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN in our study were analgesic–antipyretic (). Although not in the top 5 of drugs most implicated in this study, antiepileptic carbamazepine counted for up to 3.92% of all the drugs implicated. Carbamazepine-induced SJS/TEN is reported to be associated with HLA allele B*1502,Citation22 whose frequency has been reported to be as high as 11.6% in Western Javanese population.Citation23 Therefore, this should also be seriously considered, especially as carbamazepine also used in off-label prescription.Citation24

It has been reported that the treatment of ADR-related diseases requires substantial financial resources, as many countries may spend 15%–20% of hospital budgets for this purpose.Citation25,Citation26 Considering the potentially serious consequences, SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN may have a significant clinical and economic impact on patients. A previous study reported that patients with ADRs may stay in the hospital 12 days longer than those without ADRs.Citation27 This can significantly affect those in developing countries due to the damaging effects of ADR-related diseases on the socioeconomic progress of those countries. SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN will increase treatment costs due to prolonged hospital stays, additional clinical investigations, and treatments. As seen in , the COI of SJS patients in our study was 119.49 USD per day for only SJS-related medication, not the cost of treatment of their primary diagnosis before SJS diagnosis. Meanwhile, with the involvement of more body surface area, the daily COI for SJS–TEN overlap and TEN patients increases to 139.21 and 162.08 USD, respectively. These are higher than a previous report from Gujarat, India, that reported 15.16, 18.04, and 22.96 USD per day for SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN, respectively, after converted to USD using the World Bank’s PPP conversion factor.Citation10,Citation14 The Gujarat study, however, only calculated the cost of medications, diagnosis, and consumables used during the hospital stay.

The average hospital stay in this study was ~9.3, 13.1, and 10.2 days for SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN, respectively. The number of hospital stays may associate to the different levels of severity and complexity of SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN patients. Patients with TEN have a more severe disease and are likely to have longer hospital stay than patients with SJS. However, these findings were less significant than those reported in a previous study in Thailand.Citation28 In particular, a longer hospital stay was observed among SJS–TEN patients than among TEN patients in our study. This finding could be explained by the fact that 8 of 15 TEN patients were died within a short period of time, thus resulting in a shorter average hospital stay than SJS–TEN patients. This result is in line with the latest study from Thailand.Citation29 In contrast to the average hospital stay in this study, TEN patients had the highest COI of the patients studied. This result is probably because TEN patients were likely to be more complicated recoveries than SJS and SJS–TEN patients.

There is currently no specific treatment for TEN or SJS because of their complex pathogenesis. Although systemic corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin are controversial, they are still the main treatment methods in many countries,Citation30 including Indonesia. In our study, most cases were treated with corticosteroids. Although corticosteroids are controversial for the treatment of SJS and TEN due to the reports on the increased risk of secondary infection and delay in epithelialization,Citation31–Citation33 they are still beneficial when started early and in an appropriate dose range.Citation34 The use of corticosteroids may be based on the idea that they may inhibit immunological responses by suppressing interferon gamma-mediated apoptosis and the functions of cytotoxic T lymphocytes.Citation35 The corticosteroids, however, have to be used cautiously for the treatment of SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN, as in our study, they have the potential for DDIs with medicines used to treat the primary disease. The most common potential DDIs of corticosteroids found in this study were its interaction with fluoroquinolone antibiotics, which may increase risk of tendinitis and tendon rupture,Citation36 with phenobarbital, which may decrease the blood level and systemic effects of corticosteroids,Citation37 and with fluconazole, which may increase the blood level and systemic effect of corticosteroids.Citation38–Citation40 Health care professionals should pay attention to this potential DDI during the treatment of SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN, as it will increase the financial burden of the patients that was already high due to these serious ADRs.

Our study, however, still have some limitations. Due to the nature of retrospective study, we cannot recognize the ethnic origin of the subjects included in this study. Thus, we cannot analyze any potential association between SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN to specific ethnic of origin and populational variances among ADRs and DDIs. Furthermore, there is also potential bias in the SJS misclassification, as erythema multiforme major, a disease usually not related to medications and with much better prognosis, is also often classified as SJS.Citation41 Although it was impossible to perform a retrospective reclassification, in our study we have minimized this misclassification bias by including only the drug-induced SJS in the study.

Conclusion

Treating physicians and pharmacists should also consider the potential DDIs between the medication given and the medication for other diseases that are independent from SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN treatments. Furthermore, our results also showed that SJS, SJS–TEN overlap, and TEN could present a considerable financial consequence to the patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Truven Health Analytics for the access to Micromedex database. No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LeeHYChungWHToxic epidermal necrolysis: the year in reviewCurr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol201313433033623799330

- MockenhauptMSevere drug-induced skin reactions: clinical pattern, diagnostics and therapyJ Dtsch Dermatol Ges20097214216019371237

- SchwartzRAMcDonoughPHLeeBWToxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. Introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesisJ Am Acad Dermatol2013692e171e113

- ChanHLSternRSArndtKAThe incidence of erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. A population-based study with particular reference to reactions caused by drugs among outpatientsArch Dermatol1990126143472404462

- GerullRNelleMSchaibleTToxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: a reviewCrit Care Med20113961521153221358399

- NaveenKNPaiVVRaiVAthanikarSBRetrospective analysis of Steven Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis over a period of 5 years from northern Karnataka, IndiaIndian J Pharmacol2013451808223543919

- RzanyBMockenhauptMStockerUHamoudaOSchopfEIncidence of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in GermanyArch Dermatol1993129810598352614

- MockenhauptMViboudCDunantAStevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: assessment of medication risks with emphasis on recently marketed drugs. The EuroSCAR-studyJ Invest Dermatol20081281354417805350

- SassolasBHaddadCMockenhauptMALDEN, an algorithm for assessment of drug causality in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: comparison with case-control analysisClin Pharmacol Ther2010881606820375998

- BarvaliyaMSanmukhaniJPatelTPaliwalNShahHTripathiCDrug-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and SJS-TEN overlap: a multicentric retrospective studyJ Postgrad Med201157211511921654132

- Garcia-DovalILeCleachLBocquetHOteroXLRoujeauJCToxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: does early withdrawal of causative drugs decrease the risk of death?Arch Dermatol2000136332332710724193

- Indonesian Statistical Agency [webpage on the Internet]Population and Gender by Regency and City in West Java Province 20152015 Available from: http://jabar.bps.go.id/linkTableDinamis/view/id/12Accessed October 15th, 2016

- Indonesian Statistical AgencyUpdates on Indonesian Socio-Economics Main IndicatiorJakartaIndonesian Statistical Agency2013

- The World Bank [webpage on the Internet]PPP conversion factor, GDP (LCU per international $) Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PPP?page=2Accessed July 1, 2015

- RamosGVGuaraldoLJapiassuAMBozzaFAComparison of two databases to detect potential drug-drug interactions between prescriptions of HIV/AIDS patients in critical careJ Clin Pharm Ther2015401636725329640

- ArenellaCYoxSEcksteinDSOusleyAExpanding the reach of a cancer palliative care curriculum through web-based dissemination: a public-private collaborationJ Cancer Educ201025341842120237885

- YamaneYAiharaMIkezawaZAnalysis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Japan from 2000 to 2006Allergol Int200756441942517713361

- HalevySGhislainPDMockenhauptMAllopurinol is the most common cause of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Europe and IsraelJ Am Acad Dermatol2008581253217919772

- GueudryJRoujeauJCBinaghiMSoubraneGMuraineMRisk factors for the development of ocular complications of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysisArch Dermatol2009145215716219221260

- SakaBBarro-TraoreFAtadokpedeFAStevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in sub-Saharan Africa: a multicentric study in four countriesInt J Dermatol201352557557923330601

- Mame ThiernoDOnSThierno NdiayeSNdiayeBSyndrome de Lyell au Sénégal: responsabilité de la thiacétazone [Lyell syndrome in Senegal: responsibility of thiacetazone]Ann Dermatol Venereol20011281213051307 French11908132

- TangamornsuksanWChaiyakunaprukNSomkruaRLohitnavyMTassaneeyakulWRelationship between the HLA-B*1502 allele and carbamazepine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a systematic review and meta-analysisJAMA Dermatol201314991025103223884208

- YuliwulandariRKashiwaseKNakajimaHPolymorphisms of HLA genes in Western Javanese (Indonesia): close affinities to Southeast Asian populationsTissue Antigens2009731465319140832

- AlrashoodSTCarbamazepineProfiles Drug Subst Excip Relat Methodol20164113332126940169

- WhiteTJArakelianARhoJPCounting the costs of drug-related adverse eventsPharmacoeconomics199915544545810537962

- BordetRGautierSLe LouetHDupuisBCaronJAnalysis of the direct cost of adverse drug reactions in hospitalised patientsEur J Clin Pharmacol2001561293594111317484

- DaviesECGreenCFTaylorSWilliamsonPRMottramDRPirmohamedMAdverse drug reactions in hospital in-patients: a prospective analysis of 3695 patient-episodesPLoS One200942e443919209224

- RoongpisuthipongWPrompongsaSKlangjareonchaiTRetrospective analysis of corticosteroid treatment in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and/or toxic epidermal necrolysis over a period of 10 years in Vajira Hospital, Navamindradhiraj University, BangkokDermatol Res Prac20142014237821

- DilokthornsakulPSawangjitRInprasongCHealthcare utilization and cost of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis management in ThailandJ Postgrad Med201662210911427089110

- SunJLiuJGongQLStevens-Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a multi-aspect comparative 7-year study from the People’s Republic of ChinaDrug Des Devel Ther2014825392547

- KimPSGoldfarbIWGaisfordJCSlaterHStevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a pathophysiologic review with recommendations for a treatment protocolJ Burn Care Rehabil19834291100

- HalebianPHCorderVJMaddenMRFinklesteinJLShiresGTImproved burn center survival of patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis managed without corticosteroidsAnn Surg198620455035123767483

- MurphyJTPurdueGFHuntJLToxic epidermal necrolysisJ Burn Care Rehabil19971854174209313122

- KardaunSHJonkmanMFDexamethasone pulse therapy for Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysisActa Derm Venereol200787214414817340021

- JagadeesanSSobhanakumariKSadanandanSMLow dose intravenous immunoglobulins and steroids in toxic epidermal necrolysis: a prospective comparative open-labelled study of 36 casesIndian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol201379450651123760320

- KhaliqYZhanelGGFluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy: a critical review of the literatureClin Infect Dis200336111404141012766835

- StjernholmMRKatzFHEffects of diphenylhydantoin, phenobarbital, and diazepam on the metabolism of methylprednisolone and its sodium succinateJ Clin Endocrinol Metab19754158878931184723

- AssanRFredjGLargerEFeutrenGBismuthHFK 506/fluconazole interaction enhances FK 506 nephrotoxicityDiabete Metab199420149527520007

- SinofskyFEPasqualeSAThe effect of fluconazole on circulating ethinyl estradiol levels in women taking oral contraceptivesAm J Obstet Gynecol199817823003049500490

- HilbertJMessigMKuyeOFriedmanHEvaluation of interaction between fluconazole and an oral contraceptive in healthy womenObstet Gynecol200198221822311506836

- Bastuji-GarinSRzanyBSternRSShearNHNaldiLRoujeauJCClinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiformeArch Dermatol1993129192968420497