Abstract

Background

Mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a common condition at the Emergency Medicine Department. Head computer tomography (CT) scans in mild TBI patients must be properly justified in order to avoid unnecessary exposure to X-rays and to reduce the hospital/transfer costs. This study aimed to evaluate which clinical factors are associated with intracranial hemorrhage in Asian population and to develop a user-friendly predictive model.

Methods

The study was conducted retrospectively at the Emergency Medicine Department in Ramathibodi Hospital, a university-affiliated super tertiary care hospital in Bangkok, Thailand. The study period was between September 2013 and August 2016. The inclusion criteria were age >15 years and having received a head CT scan after presenting with mild TBI. Those patients with mild TBI and no symptoms/deterioration after 24 h of clinical observation were excluded. The predictive model and prediction score for intracranial hemorrhage was developed by multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results

During the study period, there were 708 patients who met the study criteria. Of those, 100 patients (14.12%) had positive head CT scan results. There were seven independent factors that were predictive of intracranial hemorrhage. The clinical risk scores to predict intracranial hemorrhage are developed with an accuracy of 92%. The score of >3 had the likelihood of intracranial hemorrhage by 1.47 times.

Conclusion

Clinical predictive score of >3 was associated with intracranial hemorrhage in mild TBI.

Keywords:

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a common condition in the emergency medicine department. TBI can be categorized according to Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score as mild (GCS 13–15), moderate (GCS 9–12), or severe (GCS <8). One study found that ~70%–90% of TBI cases presented in the emergency medicine department were classified as being mild.Citation1 However, neurological observation in this group is often neglected compared with moderate and severe cases, which means that intracranial hemorrhage may be missed in some cases.Citation2

Computer tomography (CT) scanning of the head is the primary screening test for diagnosis of cerebral hemorrhage in TBI patients.Citation3 Only 15%–30% of mild TBI patients have abnormal CT scans and only 1% require neurological consultation.Citation4 Therefore, head CT scans in mild TBI patients must be properly justified in order to avoid unnecessary exposure to X-rays and to reduce the hospital/transfer costs in rural facilities that the process entails.Citation5 Emergency physicians play an important role in deciding if mild TBI patients require head CT scans.Citation6

The Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria are the clinical tools that can be used to select mild TBI patients for head CT scans. Both indicators have been shown to diagnose intracranial hemorrhage with a sensitivity of 85%.Citation6,Citation7 Although the Canadian CT Head Rule is more specific than the New Orleans Criteria (60% vs 26%),Citation7,Citation8 the latter has the main advantage of being able to correctly select those patients with a high risk of intracranial hemorrhage. Further studies are required to confirm these findings and also conduct in other ethnicities. This study was aimed to evaluate which clinical factors are associated with intracranial hemorrhage in mild TBI patients. A user-friendly predictive model was also developed.

Methods

The study was conducted retrospectively at the Emergency Medicine Department in Ramathibodi Hospital, a university-affiliated super tertiary care hospital in Bangkok, Thailand. The study period was between September 2013 and August 2016. The inclusion criteria were age >15 years and having received a head CT scan after presenting with mild TBI. Those patients with mild TBI who had no symptoms were excluded.

The variables examined in this study, including baseline characteristics and potential clinical factors for intracranial hemorrhage, were recorded for all eligible patients.Citation7,Citation8 Clinical factors for intracranial hemorrhage included gender, age, baseline GCS, clinical signs of skull fracture, clinical signs of basilar skull fracture, a GCS drop ≥2 points, posttraumatic vomiting, focal neurological signs, seizure, headache, severe headache (visual analog scale [VAS] >7), posttraumatic amnesia (<1 h), transient loss of consciousness, large extracranial hematoma/severe maxillofacial injury, coagulopathy, trauma mechanisms, and drug/alcohol intoxication. The transient loss of consciousness is defined by loss of consciousness over 15 min or observed/witnessed loss of consciousness.Citation1,Citation6 The large extracranial hematoma was any extracranial hematoma with a diameter of >5 cm, while severe maxillofacial injury is defined by the presence of any fracture over clavicle.Citation6

The outcome of the study was a head CT scan that was positive for epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, or cerebral contusion. All of the head CT results were officially reported by a radiologist. All eligible patients were categorized into two groups according to head CT scan results: positive CT scan and negative CT scan.

Statistical analysis

All studied variables were compared between the two groups categorized by CT scan results using descriptive statistics. The predictive power of each variable for a positive head CT scan was calculated using univariable logistic regression and presented as an area under the receiver operating characteristic (AuROC) curve and 95% CI. Clinical predictors with high discriminative performance (AuROC curve), statistical significance (p-value), and were related with clinical relevancy were categorized into two levels using odds ratio calculation under multivariable logistic regression. Regression coefficients of each level for each clinical predictor were divided by the smallest coefficients of the model and rounded to the nearest 0.5, resulting in an item risk score. The coefficients were changed into item scores and added together into a single score. The patients were classified into low-, moderate-, and high-probability categories according to this score. Discrimination of the prediction scores was presented as AuROC curve and 95% CI for the clinical risk score of intracranial hemorrhage. Calibration of the prediction was presented using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. The score-predicted risk of intracranial hemorrhage and the observed risk were presented in a graph. The number of reports and percentages of each group were presented with the likelihood ratio of positive result (LHR+), 95% CI, and p-value.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Faculty of Medicine Committee on Human Rights Related to Research Involving Human Subjects at Mahidol University’s Ramathibodi Hospital. An informed consent was waived and accepted by the ethics committee due to retrospective study design.

Results

During the study period, there were 708 patients who met the study criteria. Of those, 100 patients (14.12%) had positive head CT scan results. There were 12 factors that were significantly associated with positive or negative head CT scan results such as male vs female sex (64.0% vs 45.6%), advanced vs young age (58.0% vs 73.4%), and GCS of ≥13 vs less (22.0% vs 3.5%). Clinical predictors with high discriminative performance (AuROC curve) were severe headache, transient loss of consciousness, posttraumatic amnesia, focal neurological signs, GCS, posttraumatic vomiting, clinical signs of skull fracture, and clinical signs of basilar skull fracture (). Severe headache and transient loss of consciousness had an AuROC curve of 0.69.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of mild TBI patients categorized by head CT scan results for any intracranial hemorrhage (CT+)

According to multivariate analysis, there were seven independent factors that were predictive of positive head CT scans, with scores ranging from 0 to 8 (). One such factor was posttraumatic amnesia, which had an adjusted OR of 1.84 and 95% CI of 0.90–3.76. It also had the smallest coefficient at 0.61 and was given a score of 1.

Table 2 Predictors of intracranial hemorrhage and assigned item score in mild TBI patients

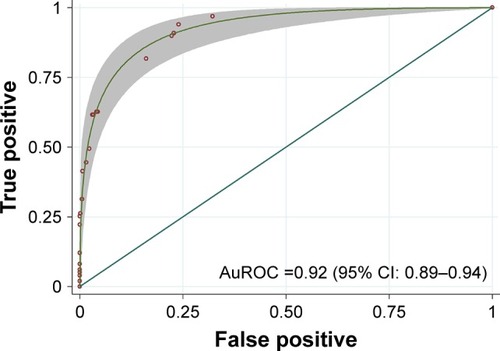

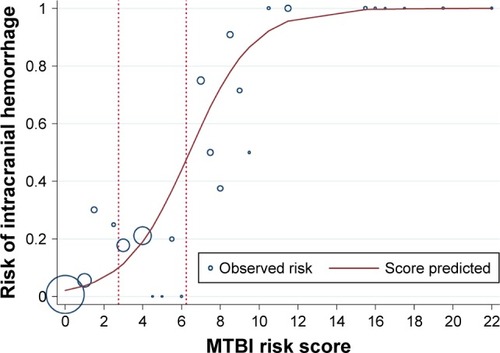

The ability of the clinical risk score to predict positive head CT scan results is presented as an AuROC curve of 92% (95% CI: 0.89–0.94; ). The measures of calibration that are presented in show the observed risk (circles) and score-predicted risk (solid line) of intracranial hemorrhage. The score-predicted risk of intracranial hemorrhage increased in close proportion to the observed risk. The risk scores were categorized into three groups: scores <3 (low risk), scores 3–6 (moderate risk), and scores >6 (high risk). The likelihood ratio of positive head CT scan was 0.13 (95% CI: 0.07–0.23) in the low-risk group, 1.47 (95% CI: 1.03–2.09) in the moderate-risk group, and 20.61 (95% CI: 12.74–33.33) in the high-risk group (; ).

Figure 1 The AuROC and 95% CI of the predictive power of the clinical risk score for intracranial hemorrhage in mild TBI patients.

Figure 2 Observed risk (circles) vs score-predicted risk (solid line) of intracranial hemorrhage in MTBI patients.

Table 3 Distribution of CT(+) vs CT(−) in low-, moderate-, and high-probability categories, LHR+, and 95% CI for intracranial hemorrhage in mild TBI patients

Discussion

Prediction of intracranial hemorrhage, as confirmed by head CT scan, has been a practical clinical challenge in mild TBI patients. Underprediction may result in misdiagnosis and delay of neurosurgical interventions.Citation4 However, conducting head CT scans in every patient who presents with mild TBI would result in a significant number of negative results, incur unnecessary expenses, and raise the patient’s lifetime cancer risk from increased radiation exposure.Citation9 In this study, 14.12% of all mild TBI patients were found to be positive for intracranial hemorrhage on a head CT scan. The overall cost of head CT scans throughout the 3 years of this study was 1,22,774 USD (~40,924 USD per year). In remote areas of developing countries or hospitals without head CT scanners, it may be necessary to transfer these patients to other hospitals in order for them to undergo a scan, which could increase the cost of medical treatment. Clinical observation may be another option, but could lead to high rates of morbidity in cases of intracranial hemorrhage.

There are several clinical prediction criteria used to determine the need for a head CT scan after mild TBI, most of which come from Western countries.Citation6,Citation10,Citation11 This study showed that clinical predictors for intracranial hemorrhage in cases of mild TBI in an Asian population were similar to those found in previous reports,Citation11–Citation15 although some factors differed in terms of power of prediction, as shown in . This study also presented the risk in terms of a more user-friendly probability risk score. Head CT scans were found to be justified in cases in which mild TBI patients had moderate or high scores (>3) (). However, those with low probability still need clinical observation and may need a head CT later, if indicated.

Table 4 Comparison of risk factors for intracranial hemorrhage in mild TBI patients by various studies

This study found four predictors for intracranial hemorrhage in cases of mild TBI, similar to those found in previous reports,Citation11–Citation15 including focal neurological signs, basilar skull fracture, transient loss of consciousness, and severe headache (VAS >7), as shown in . Unlike other reports,Citation11–Citation15 age >60 years, posttraumatic amnesia, posttraumatic vomiting, seizure, and anticoagulant use were not significant predictors for intracranial hemorrhage in this study. The nonsignificance of the last three factors may be explained by the small sample size (). Even though age >60 years and posttraumatic amnesia were found to be significant by univariate analysis, they were not significant when compared with other factors using multivariate analysis ( and ). These findings indicated that both factors were not independent risk factors for intracranial hemorrhage. Another possible explaination for different predictors of this study when compared with other studies from the Western countries is the study population. Race may have effects on clinical symptoms of mild TBI.

Regarding the accuracy of the model, this study provided 92% accuracy. This percentage was somewhat lower than the previous study conducted in the Netherlands (96%).Citation13 The previous study used 10 major and 8 minor predictors in 3,181 mild TBI patients. Having at least one major or two minor predictors gave the 96% sensitivity. This study had a lower accuracy rate that may be explained by a smaller sample size.

There are some limitations to this study. First, this study was conducted only in tertiary university hospitals with small numbers of subjects than previous studies.Citation7,Citation12 The results may not be applicable in other types of health-care facilities. In addition, further studies are needed in other Asian populations. Moreover, some of the factors that were considered, such as medication use and basilar skull fracture, appeared only in a small number of patients. This may have led to a wide 95% CI (). Due to retrospective data collection, there might be few missing patients with mild TBI at the emergency room or other departments. Another limitation was that intracranial hemorrhage in this study included all types of hemorrhages. Finally, it would be beneficial to conduct a cost-effective study to evaluate the risks and benefits of head CT scans in mild TBI.

In conclusion, a user-friendly model for predicting intracranial hemorrhage in mild TBI was developed. A clinical predictive score of >3 was associated with intracranial hemorrhage in mild TBI.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Thailand Research Fund (TRF) (IRG 5780016), the TRF Senior Research Scholar Grant from the Thailand Research Fund (TRF grant number RTA5880001), the Higher Education Research Promotion and National Research University Project of Thailand, Office of the Higher Education Commission, Thailand, through the Health Cluster (SHeP-GMS), Khon Kaen University, and the grant from Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Thailand (Grant Number RG59301).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CassidyJDCarrollLJPelosoPMWHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain InjuryIncidence, risk factors and prevention of mild traumatic brain injury: results of the WHO Collaborating Center Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain InjuryJ Rehabil Med200443 Suppl2860

- GalbraithSMisdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis in traumatic intracranial haematomaBr Med J19761602314381439986221

- ManolakakiDVelmahosGCSpaniolasKEarly magnetic resonance imaging is unnecessary in patients with traumatic brain injuryJ Trauma20096641008101219359907

- BorgJHolmLCassidyJDDiagnostic procedures in mild traumatic brain injury: results of the WHO Collaborating Center Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain InjuryJ Rehabil Med200443 Suppl617515083871

- LaupacisASekarNStiellIGClinical prediction rules: a review and suggested modifications of methodological standardsJAMA199727764884949020274

- StiellIGClementCMRoweBHComparison of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria in patients with minor head injuryJAMA2005294121511151816189364

- BouidaWMarghliSSouissiSPrediction value of the Canadian CT head rule and the New Orleans criteria for positive head CT scan and acute neurosurgical procedures in minor head trauma: a multicenter external validation studyAnn Emerg Med201361552152722921164

- PapaLStiellIGClementCMPerformance of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria for predicting any traumatic intracranial injury on computed tomography in a United States Level I trauma centerAcad Emerg Med201219121022251188

- BrennerDEllistonCHallEBerdonWEstimated risks of radiation-induced fatal cancer from pediatric CTAJR Am J Roentgenol2001176228929611159059

- HaydelMJPrestonCAMillsTJLuberSBlaudeauEDeBlieuxPMIndications for computed tomography in patients with minor head injuryN Engl J Med2000343210010510891517

- VosPEBattistinLBirbamerGEFNS guideline on mild traumatic brain injury: report of an EFNS task forceEur J Neurol20029220721911985628

- SmitsMDippelDWde HaanGGExternal validation of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria for CT scanning in patients with minor head injuryJAMA2005294121519152516189365

- SmitsMDiederikWDippelWPredicting intracranial traumatic findings on computed tomography in patients with minor head injury: the CHIP prediction ruleAnn Intern Med2007146397405

- IbanezLChanSSilvaJReliability of clinical guidelines in the detection of patients at risk following mild head injury: results of a prospective studyJ Neurosurg2004100582583415137601

- FabbriAServadeiFMarchesiniGClinical performance of NICE recommendations vs NCWFNS proposal in patients with mild head injuryJ Neurotrauma200522121419142716379580