Abstract

Ground-glass nodule (GGN) is defined as a nodular shadow with ground-glass opacity that is generally associated with the early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Nowadays, GGNs of the lung are increasingly detected with thin-section computed tomography scan. GGNs are categorized as pure GGNs and mixed GGNs according to the images from a high-resolution computed tomography. Meanwhile, it is routine to divide GGNs into different categories according to the number, solitary, or multiple, the management of which there is very different. A great number of studies have been conducted to analyze the different characteristics of GGNs in various aspects ranging from radiology, pathology, and surgery to molecular biology. However, plenty of problems still remain unsolved, ranging from the preoperative localization to intraoperative surgical resection procedure, the lymphadenectomy, and sampling of lymph nodes, as well as the accuracy of frozen sections. There has been a large volume of updated published information summarizing recently emerging and rapidly progressing aspects of surgical treatment of solitary and multiple GGNs with the unsolved problems mentioned above. However, there have been few specific reviews of surgical treatment of GGNs so far. This review presents a timely outline of advances in relevant experience and controversies of GGNs for a better understanding of this kind of lesion.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide. With low-dose computed tomography accepted as an effective screening method in high-risk individuals for the purpose of reducing lung cancer mortality,Citation1 the detection of ground-glass nodule (GGN) has been increased remarkably all over the world, especially in China. Ground-glass opacity (GGO) is defined as an area of hazy increased attenuation of the lung with preservation of bronchial and vascular margins. GGN is a nodular shadow with GGO, which is a nonspecific finding on high-resolution computed tomography lung images and has been described as haziness with increased lung attenuation and preserved bronchial and vascular margins.Citation2 GGN on images may represent alveolar changes or interstitial changes, with increased cellularity and fluid within the alveolar wall.Citation1 Apart from the malignant disease, which is often a focal finding, GGN changes can represent lung infections (which may be visualized as patchy findings scattered throughout the parenchyma), lung edema with fluid in the interstitium, patchy increased parenchymal perfusion, or interstitial diseases (where GGN can represent disease activity and may precede irreversible changes, including the development of fibrosis).Citation3 Several studies have shown that persistent GGN on CT should be suspected with a high risk of malignancy,Citation4,Citation5 and these nodules were mainly adenocarcinoma, which are characterized by histologic heterogeneity. Malignant nodules presenting as GGNs are regarded as low-grade malignancies with three subtypes: adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA), and lepidic adenocarcinoma.Citation6 This review focuses on the perioperative management and surgical treatment of GGNs based on different categories.

Categories of GGNs

GGNs, also referred to as subsolid nodules,Citation1 are radiologically divided into two categories: pure GGNs (pGGNs), which contain no solid component, and part-solid GGNs, which contain both a pure GGO region and a consolidated regionCitation7 and are therefore also called mixed GGNs (mGGNs). mGGNs are more frequently pathologically diagnosed as invasive adenocarcinoma; however, AIS and MIA more often present as pGGNs on the contrary.Citation8 In malignant part-solid GGNs, the solid part histologically represents invasion, whereas the pure GGO areas are considered as lepidic components of adenocarcinoma. Solid transformation of GGNs is thus considered a strong indicator of malignancy.Citation9 A study showed that, based on the proportion of the solid component, called the consolidation/tumor ratio (CTR), it may be possible to differentiate between invasive and noninvasive malignant diseases.Citation10 According to Oh et al,Citation2 when only histologically confirmed cases were included, the malignancy rates of pGGNs and mGGNs were 70% and 89.6%, respectively, which are similar to the 71.4% and 89.6% reported by Nakata et al.Citation11 shows a brief comparison of pGGNs and mGGNs.

Table 1 Comparison of the characteristics of pure GGNs and mixed GGNs

Surgical treatment of solitary GGN

Nowadays, video-assisted surgery (VATS) is increasingly applied to the treatment of GGNs instead of conventional thoracotomy with less ports and smaller incisions, which has been Nowadays, video-assisted surgery (VATS) is increasingly applied to the treatment of GGNs instead of conventional thoracotomy with less ports and smaller incisions, which has been proved as a superior surgical method. Despite certain contraindications, VATS predominates the overwhelming majority of the surgical treatment of solitary GGN. There are several parts to be noted in VATS of GGN, which are discussed in the following sections.

Preoperative localization of GGNs

Since there is difficulty in judging the precise location of small GGOs with tactile sensation or naked eyes, it is of necessity to perform preoperative localization before surgeries to avoid the unnecessary intraoperative expansion of resection extension. Various methods have been applied to localize GGNs mainly including percutaneous puncture to place markers; percutaneous injection of colored collagen, dye, lipiodol, agar, and radiotracer technetium (99m) macroaggregates; and computer-assisted navigation and localization.

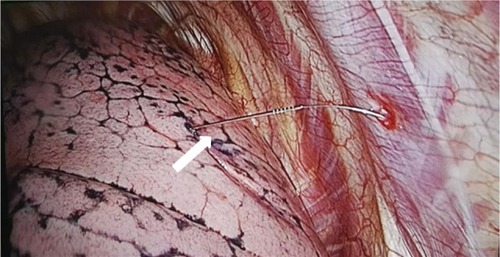

The preoperative CT-guided hookwire localization for pulmonary nodules, particularly for GGNs, is one of the most common localization methods, which has been proved to be an effective and safe technique to assist VATS resection of the nodules. It can increase the ratio of lung wedge resection with little complications and may be better used in clinical diagnosis and treatment of small pulmonary nodules with VATS.Citation12 Although there has been no unified standard for CT-guided hookwire localization so far, some clinicians proposed the following indications for using CT-guided hookwire localization: 1) GGNs with a diameter ≤20 mm, or solid nodule ≤10 mm; 2) nodules located at the outer one third of lung fields; 3) nodules with distance to visceral pleura ≥10 mm for solid nodules and ≥5 mm for GGNs; and 4) nodules not adjacent to visceral pleura, no pleural tag in other word.Citation12 Notably, our previous experience also showed that the placement of a hookwire may cause tearing of the lung parenchyma with the potential for intrapulmonary hemorrhage and/or failed nodule localization if a pneumothorax develops.Citation13 shows the photo of intraoperative hookwire device.

Figure 1 The pulmonary nodule was located by the hookwire insertion.

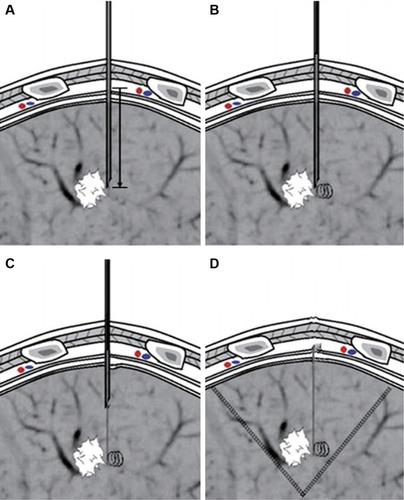

CT-guided microcoil localization for pulmonary small nodules prior to VATS is another common method, which decreases the need for thoracotomy or VATS anatomic resection and increases the success rate of VATS excision for the diagnosis of small peripheral pulmonary nodules. Preoperative localization using microcoil was conducted in lesions according to the following conditions: 1) solid nodules with a diameter ≤1 cm and distance to visceral pleura ≥0.5 cm; 2) GGO; and 3) part-solid GGO, with a solid portion ≤1 cm and distance to the visceral pleura ≥1 cm.Citation14 Guidance with the use of methylene blue dye is limited by its potential to diffuse away from the nodule such that fixed time intervals between localization and surgical resection are required. Microcoil localization can make up for the deficiencies of other methods: 1) compared with the commonly used hookwire, the microcoil can be retained in the patient’s body and is not easily detached. Therefore, it is not necessary to perform surgery immediately after the localization. For the “blind areas” of the hookwire technique, CT-guided microcoil placement is an effective method of marking GGO lesions that makes thoracoscopic wedge resection easier;Citation15 2) compared with solvents such as iodine, complications caused by intravascular injection and solvent diffusion effects on localization need not be concerned; and 3) compared with radionuclide, microcoil cannot be contaminated through radiation and does not require special equipment and personnel training.Citation14 A novel technique in which a vascular embolization coil is inserted into the lung nodules under CT guidance has also been reported, and the marked nodules are subsequently resected via VATS under fluoroscopic guidance in a hybrid operating room.Citation16 Therefore, microcoil localization is believed to be the most ideal method worthy of recommending. shows the picture of a microcoil, and illustrates the schematic diagram of “trailing method” for deploying the microcoil. Meanwhile, preoperative injection of patent blue vital dye or cyanoacrylate is another feasible, safe, and accurate procedure,Citation17 which makes VATS easier for small, poorly located pulmonary nodules with GGO predominance and synchronous multiple nodules, which can avoid the rapid diffusion of methylene blue into surrounding parenchyma. Furthermore, peripheral GGNs can be located accurately by three-dimensional localization technique on chest wall surface and performing bronchoscopy procedures to increase diagnostic yields, which is claimed as a more convenient, economical, and reliable method with the similar diagnostic yields as radial endobronchial ultrasound-guided method.Citation18 With unceasing exploration and summary of advantages and disadvantages of current localization methods, some better novel methods may be applied to the preoperative localization of GGNs in the near future.

Figure 2 The deep lesion was located by the microcoil on the visceral pleura surface under thoracoscopic guidance.

Figure 3 Schematic diagram of “trailing method” for deploying the microcoil.

Lobectomy versus sublobar resection

When a malignant diagnosis has been made, surgery is the primary curative treatment option. Although lobectomy is considered the standard surgical treatment for the majority of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the operation procedure for patients with stage IA NSCLC (T1a, tumor diameter ≤2 cm) remains controversial. Therefore, multiple retrospective and prospective studies have been implemented to make comparisons of the outcomes after lobectomy and sublobar resection (segmentectomy and wedge resection).

In the past, sublobar resection has primarily been reserved for operable, but high-risk patients in whom the optimal surgical approach must be modified.Citation1 However, in recent years, considerable prospective trials have been registered to evaluate sublobectomy in non–high-risk patients in the USA, Japan, and China. In some cases, sublobectomy may offer the same long-term survival as lobectomy without an increase in the likelihood of local recurrence.Citation19,Citation20 Wedge resection has been proved to successfully treat GGO-dominant (GGO component >50%) clinical stage IA adenocarcinomas of a T1a tumor and so has segmentectomy of a T1b tumor.Citation20 It has also been reported that GGO-predominant clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma (pGGNs) showed a 100% survival after wedge resection.Citation21 There is another viewpoint that the outcomes of VATS lobectomy and segmentectomy procedures for clinical stage I NSCLC were equivalent, while the outcome of VATS wedge resection was inferior.Citation22 On the contrary, there is also a differing opinion that sublobectomy including segmentectomy and wedge resection causes a lower survival rate than that of lobectomy in clinical stage IA (T1a) patients.Citation23–Citation25 Notably, clinical stage I lung cancer patients who underwent sublobectomy after intentional selection can achieve comparable survival as those who had lobectomy.Citation24,Citation26

Sublobectomy is recommended to be considered for GGNs in cIA stage, which is predicted to be AIS or MIA or in which the maximum diameter is <2 cm, while intentional sublobar resection is not recommended in stage I tumors >2 cm.Citation26,Citation27 With sublobar resection, our previous study showed that the long-term outcomes of wedge resection are inferior to segmentectomy for NSCLC patients with a tumor size of >1–2 cm,Citation25 while the two procedures are almost equivalent for NSCLC patients with a tumor size of <1 cm. However, there is a controversy that segmentectomy is claimed to result in higher survival rates compared with wedge resection for patients with stage I NSCLC, whereas the outcomes of wedge resection are comparable to those of segmentectomy for stage IA NSCLC patients with a tumor size of 2 cm.Citation28 Another retrospective review shared a similar conclusion that, for stage cT1N0-NSCLC patients, the outcomes of wedge resection are comparable to those of segmentectomy in which a more thorough lymph nodes dissection in segmentectomy does not translate to a survival benefit.Citation29 Our previous experience concluded that wedge resection can be performed on pGGNs in a favorable site, with a margin width of >2 cm,Citation30 while wedge resection should be carefully considered for patients with mGGNs (CTR >0.25) because of the high recurrence rate.Citation19 If the lesion is deep in site while still within a certain lung segment, segmentectomy can be considered. If the lesion locates between two segments or more, or at the root segment of bronchus, lobectomy should be performed then.Citation30 Furthermore, if intraoperative biopsy for group N1 or N2 lymph nodes is positive, it is necessary to implement lobectomy.Citation30 In addition, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline for NSCLC (Version 1.2016) recommended that segmentectomy and wedge resection should achieve parenchymal resection margin of ≥2 cm or greater or equal to the nodule size.Citation31 To be noted, margin width did not influence the recurrence in GGO-predominant tumors, while narrow margin width (resection margin ≤5 mm) was a significant risk factor for the recurrence of solid-predominant tumors.Citation32 All together, it is necessary to work out a definite standard for surgical procedures in GGNs with different size, components, and pathological results, and patient profile should be taken into consideration when designing an individualized operation.

Lymph nodes dissection or sampling

Lobectomy with complete systematic lymph node (SLN) dissection has been established as the standard surgical treatment of resectable NSCLC. In addition to different resection methods, the effectiveness of mediastinal lymph node was another focus to evaluate in a patient with GGNs. The performance of mediastinal lymph node evaluation (MLE) is recommended in most NSCLC patients, since occult lymph node metastasis may occur even in clinical N0 patients.Citation27,Citation33–Citation35 MLE methods include mediastinal lymph node dissection (MLND) and mediastinal lymph node sampling (MLS). Even though MLND is generally considered to give more accurate nodal staging, whether MLND is associated with greater survival compared with MLS is controversial.Citation27,Citation33 In a retrospective analysis, 358 patients with N0 NSCLC, which had a diameter ≤3 cm, were divided into three groups with either GGO-predominant or solid-predominant tumor: no mediastinal lymph node evaluation (NoMLE) group, MLS group, and MLND group.Citation36 There was no difference found in the 5-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) rate among three groups in the GGO-predominant patients; however, in the solid-predominant tumor group, the 5-year RFS rate of the NoMLE group was lower than in the MLND group (48.6% vs 73.1%, P=0.007). Therefore, MLE was not a significant risk factor for recurrence in GGO-predominant tumor, and it was not an essential procedure for clinical N0 NSCLC presenting as ≤3 cm GGO-predominant nodules.Citation36 Furthermore, patients with clinical N0/N1 NSCLC were found having similar recurrence rates and survival with lobe-specific and complete mediastinal SLN sampling,Citation37 and lobe-specific mediastinal nodal evaluation seems to be acceptable in patients with early-stage NSCLC. Meanwhile, there are several studies drawing similar conclusions that there were no cases with hilar and mediastinal lymph node metastasis in GGO-predominant tumors, and MLS/selective LND is acceptable in patients with c-stage I NSCLC with GGO-predominant tumors.Citation38,Citation39 However, solid-predominant nodules and elevated serum carcinoembryonic antigen level were associated with a higher preference for nodal metastasis in which MLND should be performed.Citation38,Citation39 The final conclusions of lymph nodes management are still in suspense waiting for the long-term survival from multicentered randomized clinical trials.

Intraoperative frozen section (FS)

In terms of accuracy of intraoperative FS, Liu et al reviewed the clinical data of 803 patients and found that the total concordance rate between intraoperative FS and final pathology was 84.4%.Citation40 When atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, AIS, and MIA were classified together as a low-risk group, the concordance rate was 95.9%. The diagnostic accuracy values of FS for tumors ≤1 cm and >1 cm in diameter were 79.6% and 90.8%, respectively (P<0.01). Most discrepant cases were the underestimation of AIS and MIA; therefore, the 5-year RFS rate (100%) was found significantly better for the patients with AIS/MIA than for patients with invasive adenocarcinoma (74.1%, P<0.01). shows the more specific information. Similarly, there was another retrospective analysis of data from 136 patients pathologically diagnosed with early-stage (T1N0M0) AIS or MIA from paraffin-embedded sections with 4.4% discordance between the FS and paraffin-embedded section diagnoses.Citation41 The reasons for FS errors and deferrals included larger tumor volume, tumor located close to the visceral pleura, interstitial inflammation or fibrosis, the absence of prominent atypia, and differential morphology in the deeper levels of the paraffin block. Although both studies drew a conclusion that precise diagnosis by intraoperative FS is an effective method to guide resection strategy for peripheral small-sized lung adenocarcinoma, there seems to be room for amelioration of the accuracy of intraoperative FS.

Table 2 Comparison of frozen section and final pathology reveals that most discrepant cases were the underestimation of AIS and MIA

Clinical management of multiple GGO nodules

Multiple or synchronous GGNs are defined as more than two GGNs found at the same time, which increasingly occurs in a greater number of patients. About 20%–30% GGN lesions resected were found to be accompanied by intrapulmonary multiple smaller GGNs.Citation30 Hitherto, the majority of clinicians consider that the presence of multifocal GGNs is primary lesions from different origins rather than intrapulmonary metastasis. Unfortunately, the surgical management of multiple GGNs is still controversial.

Although surgical approaches for such multiple lesions depend on their anatomical location, size, and number, as well as the patient’s age and pulmonary function, the decision usually depends on the surgeon’s judgment; no standard criteria have been established for the selection of the lesions to be treated, nor the method of management of the residual nodules in cases of synchronous multifocal GGNs. Shimada et al proposed their basic treatment strategy for ipsilateral synchronous multiple lung lesions as follows: when tumors were in an ipsilateral chest, the resection of all lesions >10 mm or radiographical solid-dominant lesions should be tried by single-stage surgical treatment.Citation42 However, for subnodules <10 mm or radiographical GGO-dominant lesions with slow growth, strict surgical resection of main cancer and easily accessible subnodules by limited resection should be performed if the excision extension was expected to be greater than sublobe because of the central position or if there were multiple lesions scattered throughout multiple lobes. In contrast, surgical resection should be performed on subnodules with a diameter of >10 mm or with an emerging solid portion. According to our experience, if the multiple GGNs are in the same lobe, wedge resection, segmentectomy, or lobectomy can be performed.Citation30 If the multiple GGNs are scattered throughout multiple lobes in the ipsilateral chest, operative approaches should be designed individually according to the location of lesions, multiple wedge resection or segmentectomy should be performed, and lung function should be preserved as much as possible based on the principle of surgical oncology. If multiple GGNs are in the contralateral chest, synchronous or two-stage VATS surgery can be implemented, while it should be cautious to perform synchronous surgery on bilateral lungs.Citation30,Citation42 This strategy has been further corroborated with the successful implementation of single-stage bilateral pulmonary resections on 29 patients by VATS for multiple GGNs with satisfying outcomes.Citation43

When tumors were in contralateral lesions, two-stage surgical treatment was commonly performed. Unless patients were capable of undergoing surgical resection, stereotactic body radiation therapy or continuous monitoring of the residual lesions may be a better choice than surgery to some extent. In addition, the prognosis of patients undergoing the resection of multiple GGNs was satisfying,Citation42–Citation47 and sublobar resection did not affect the prognosis of multifocal GGNs.Citation48,Citation49 The overall survival of patients will not be affected once the main cancer is resected no matter whether residual subnodules remain growing or new GGNs appear.Citation50 In addition, size was found to be an independent risk factor in assessing the malignant potential of synchronous pGGNs before surgery, and the cutoff value was 9.4 mm.Citation51 Sublobar resection is also believed to be an appropriate choice for synchronous pGGNs.Citation52

It is another focus for thoracic surgeons to perform MLND or MLS in multiple GGNs. It has been found that CTR is closely related to lymph node metastasis in multiple GGNs.Citation53 A CTR of main cancer >0.5 was identified as an independent predictor of unfavorable RFS on multivariate analysis.Citation42 This viewpoint was corroborated in a review of 876 cases of cIA lung adenocarcinoma,Citation38 in which 133 cases with CTR <0.5 undergoing systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy were found to have no hilar or mediastinal lymph node metastasis, whereas in 12% of cases with CTR ≥0.5 the presence of lymph node metastasis was found. Noteworthy, a CTR ≥89% is considered a predictor of mediastinal lymph node metastasis on a multivariate analysis with 894 cases of IA peripheral NSCLC recruited.Citation54 These data may help surgeons make a better judgment on the necessity of MLND, while further prospective trials are required for an optimal treatment strategy. Hitherto, it is plausible to perform a limited resection and MLS in multiple GGNs with CTR <0.5, and lobectomy should be considered for solid-predominant GGNs with residual nodules left monitored.

Discussion

Although plenty of retrospective analysis has been performed, there have been no sufficient data from multicentered prospective trials to offer potent evidence and therefore no optimal choices for the management of patients with GGNs so far, especially for those with multiple GGNs. Although surgical resection, specifically lobectomy, is currently the standard of care for early-stage lung cancer, it is not clear that this is necessarily the optimal approach for patients with GGNs who are ultimately diagnosed with lung cancer, of whom the tumor biology may be different from that of patients with historically diagnosed lung cancer. Therefore, it is meaningful to make a comparison of lobectomy and wedge resection or segmentectomy according to intraoperative frozen pathology for early-stage lung cancers with GGNs. Since the role of more limited surgical resection is being explored, alternative treatment strategies such as stereotactic ablative body radiation are also being considered with an indefinite superiority or inferiority compared with operations. In addition, according to the current research, there was no lymph node metastasis in AIS and MIA cases present as pGGNs. Therefore, a definite conclusion is also needed on whether nodal dissection can be waived in such cases, most possibly with very minimal chance of nodal involvement. In recent years, with the rising of nonintubated uniportal VATS for the management of peripheral lung nodules, the quality of postoperative life and outcomes of patients should be further discussed compared with intubated ones for minimal invasion. Last but not least, risk factors of surgical procedure and postoperative complications are also worth our attention and consideration.

In multiple GGNs, since pGGNs are nonspecific imaging findings, preoperative diagnosis is always unclear before the primary operation. Once a carcinomatous pGGN is neglected, an ipsilateral reoperation with a higher risk may be inevitable. As a result, it is of clinical significance for thoracic surgeons to determine which synchronous pGGN has the highest potential of malignancy. Meanwhile, it is doubtless valuable to find the effect of primary cancer (T stage, N stage, and overall stage of primary tumor) on the malignant potential of multiple GGNs and the interactions between multiple GGNs with large samples and data. Meanwhile, it merits further comparison of single-stage bilateral pulmonary resections by VATS and two-stage procedures for multiple GGNs, which promotes the experience of indications for simultaneous bilateral resection.

Conclusion

In summary, it is necessary to reassess and renew the guideline of treatment strategy for GGNs on the resection procedure and mediastinal lymph node management. The diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary nodules should start from assessing the probability of malignancy and in turn evaluating the pros and cons of surgery, including the consequences of treatment, taking into account personal physical condition, complications, and preference. Surgery is preferred for patients with a high probability of malignancy.Citation30 More research from clinical viewpoints is needed to understand GGNs better for individualized surgical treatment.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PedersenJHSaghirZWilleMMThomsenLHSkovBGAshrafHGround-glass opacity lung nodules in the era of lung cancer CT screening: radiology, pathology, and clinical managementOncology (Williston Park)20163026627426984222

- OhJYKwonSYYoonHIClinical significance of a solitary ground-glass opacity (GGO) lesion of the lung detected by chest CTLung Cancer200755677317092604

- RidgeCABankierAAEisenbergRLMosaic attenuationAJR Am J Roentgenol2011197W970W97722109341

- KimHYShimYMLeeKSHanJYiCAKimYKPersistent pulmonary nodular ground-glass opacity at thin-section CT: histopathologic comparisonsRadiology200724526727517885195

- HenschkeCIYankelevitzDFMirtchevaRCT screening for lung cancer: frequency and significance of part-solid and nonsolid nodulesAJR Am J Roentgenol20021781053105711959700

- MoonYSungSWLeeKYParkJKClinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of non-lepidic invasive adenocarcinoma presenting as ground glass opacity noduleJ Thorac Dis201682562257027747010

- MacMahonHNaidichDPGooJMGuidelines for management of incidental pulmonary nodules detected on CT images: from the Fleischner Society 2017Radiology201728422824328240562

- QiuZXChengYLiuDClinical, pathological, and radiological characteristics of solitary ground-glass opacity lung nodules on high-resolution computed tomographyTher Clin Risk Manag2016121445145327703366

- LeeHYChoiYLLeeKSPure ground-glass opacity neoplastic lung nodules: histopathology, imaging, and managementAJR Am J Roentgenol2014202W224W23324555618

- AsamuraHHishidaTSuzukiKRadiographically determined noninvasive adenocarcinoma of the lung: survival outcomes of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group 0201J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg2013146243023398645

- NakataMSaekiHTakataIFocal ground-glass opacity detected by low-dose helical CTChest20021211464146712006429

- WangTMaSYanTComputed tomography guided hook-wire precise localization and minimally invasive resection of pulmonary nodulesZhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi201518680685 Chinese26582223

- ShiZChenCJiangSJiangGUniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery resection of small ground-glass opacities (GGOs) localized with CT-guided placement of microcoils and palpationJ Thorac Dis201681837184027499978

- SuiXZhaoHYangFLiJLWangJComputed tomography guided microcoil localization for pulmonary small nodules and ground-glass opacity prior to thoracoscopic resectionJ Thorac Dis201571580158726543605

- ZuoTShiSWangLSupplement CT-guided microcoil placement for localising GGO lesions at “blind areas” of the conventional hook-wire techniqueHeart Lung Circ20172669670128089791

- LiuLZhangLJChenBNovel CT-guided coil localization of peripheral pulmonary nodules prior to video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a pilot studyActa Radiol20145569970624078457

- LinMWTsengYHLeeYFComputed tomography-guided patent blue vital dye localization of pulmonary nodules in uniportal thoracoscopyJ Thorac Cardiovasc Surg2016152535544.e227189890

- DengCCaoXWuDSmall lung lesions invisible under fluoroscopy are located accurately by three-dimensional localization technique on chest wall surface and performed bronchoscopy procedures to increase diagnostic yieldsBMC Pulm Med20161616627894283

- TsutaniYMiyataYNakayamaHOncologic outcomes of segmentectomy compared with lobectomy for clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma: propensity score-matched analysis in a multicenter studyJ Thorac Cardiovasc Surg201314635836423477694

- TsutaniYMiyataYNakayamaHAppropriate sublobar resection choice ground glass opacity–dominant clinical stage IA adenocarcinoma: wedge resection or segmentectomyChest2014145667124551879

- ChoJHChoiYSKimJKimHKZoJIShimYMLong-term outcomes of wedge resection for pulmonary ground-glass opacity nodulesAnn Thorac Surg20159921822225440277

- NakamuraHTaniguchiYMiwaKComparison of the surgical outcomes of thoracoscopic lobectomy, segmentectomy, and wedge resection for clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancerThorac Cardiovasc Surg20115913714121480132

- LiuYHuangCLiuHChenYLiSSublobectomy versus lobectomy for stage IA (T1a) non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis studyWorld J Surg Oncol20141213824886396

- ZhangYSunYWangRYeTZhangYChenHMeta-analysis of lobectomy, segmentectomy, and wedge resection for stage I non-small cell lung cancerJ Surg Oncol201511133434025322915

- DaiCShenJRenYChoice of surgical procedure for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer ≤1 cm or >1 to 2 cm among lobectomy, segmentectomy, and wedge resection: a population-based studyJ Clin Oncol2016343175318227382092

- SunHHSestiJDoningtonJSSurgical treatment of early I stage lung cancer: what has changed and what will change in the futureSemin Respir Crit Care Med20163770871527732992

- DarlingGECurrent status of mediastinal lymph node dissection versus sampling in non-small cell lung cancerThorac Surg Clin20132334935623931018

- HouBDengXFZhouDLiuQXDaiJGSegmentectomy versus wedge resection for the treatment of high-risk operable patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysisTher Adv Respir Dis20161043544327585599

- AltorkiNKKamelMKNarulaNAnatomical segmentectomy and wedge resections are associated with comparable outcomes for patients with small cT1N0 non-small cell lung cancerJ Thorac Oncol2016111984199227496651

- JiangGXieDEarly-stage lung cancer manifested as ground-glass opacityZhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi201553790793 Chinese26654312

- ZhanPXieHXuCHaoKHouZSongYManagement strategy of solitary pulmonary nodulesJ Thorac Dis2013582482924409361

- GouldMKDoningtonJLynchWREvaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelinesChest2013143e93Se120S23649456

- HuangXWangJChenQJiangJMediastinal lymph node dissection versus mediastinal lymph node sampling for early stage non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysisPLoS One20149e10997925296033

- YeBChengMLiWPredictive factors for lymph node metastasis in clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinomaAnn Thorac Surg20149821722324841547

- MoonYKimKSLeeKYSungSWKimYKParkJKClinicopathologic factors associated with occult lymph node metastasis in patients with clinically diagnosed N0 lung adenocarcinomaAnn Thorac Surg20161011928193526952299

- MoonYSungSWNamkoongMParkJKThe effectiveness of mediastinal lymph node evaluation in patient with ground glass opacity tumorJ Thorac Dis201682617262527747016

- ShapiroMKadakiaSLimJLobe-specific mediastinal nodal dissection is sufficient during lobectomy by video-assisted thoracic surgery or thoracotomy for early-stage lung cancerChest20131441615162123828253

- ZhaJXieDXieHRecognition of “aggressive” behavior in “indolent” ground glass opacity and mixed density lesionsJ Thorac Dis201681460146827499932

- HarukiTAokageKMiyoshiTMediastinal nodal involvement in patients with clinical stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: possibility of rational lymph node dissectionJ Thorac Oncol20151093093626001143

- LiuSWangRZhangYPrecise diagnosis of intraoperative frozen section is an effective method to guide resection strategy for peripheral small-sized lung adenocarcinomaJ Clin Oncol20163430731326598742

- HePYaoGGuanYLinYHeJDiagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma in situ and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma from intraoperative frozen sections: an analysis of 136 casesJ Clin Pathol2016691076108027174927

- ShimadaYSajiHOtaniKSurvival of surgical series of lung cancer patients with synchronous multiple ground-glass opacities, and the management of their residual lesionsLung Cancer20158817418025758554

- YaoFYangHZhaoHSingle-stage bilateral pulmonary resections by video-assisted thoracic surgery for multiple small nodulesJ Thorac Dis2016846947527076942

- NakataMSawadaSYamashitaMSurgical treatments for multiple primary adenocarcinoma of the lungAnn Thorac Surg2004781194119915464469

- MunMKohnoTEfficacy of thoracoscopic resection for multifocal bronchioloalveolar carcinoma showing pure ground-glass opacities of 20 mm or less in diameterJ Thorac Cardiovasc Surg200713487788217903500

- RobertsPFStraznickaMLaraPNResection of multifocal nonsmall cell lung cancer when the bronchioloalveolar subtype is involvedJ Thorac Cardiovasc Surg20031261597160214666039

- BattafaranoRJMeyersBFGuthrieTJCooperJDPattersonGASurgical resection of multifocal non-small cell lung cancer is associated with prolonged survivalAnn Thorac Surg20027498899412400733

- HattoriAMatsunagaTTakamochiKOhSSuzukiKSurgical management of multifocal ground-glass opacities of the lung: correlation of clinicopathologic and radiologic findingsThorac Cardiovasc Surg20176514214926902328

- CarrettaACiriacoPMelloniGSurgical treatment of multiple primary adenocarcinomas of the lungThorac Cardiovasc Surg200957303419169994

- WangQJiangWXiJSurgery for pulmonary multiple ground glass opacitiesZhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi201619355358 Chinese27335296

- DaiCRenYXieHClinical and radiological features of synchronous pure ground-glass nodules observed along with operable non-small cell lung cancerJ Surg Oncol201611373874427041153

- SihoeADVan SchilPNon-small cell lung cancer: when to offer sublobar resectionLung Cancer20148611512025249427

- KimHKChoiYSKimKManagement of ground-glass opacity lesions detected in patients with otherwise operable nonsmall cell lung cancerJ Thorac Oncol200941242124619687762

- KoikeTKoikeTYamatoYYoshiyaKToyabeSPredictive risk factors for mediastinal lymph node metastasis in clinical stage Ia non-small-cell lung cancer patientsJ Thorac Oncol201271246125122659962