Abstract

Background

Vitamin B12 deficiency, which may cause serious neuropsychiatric damage, is common in the elderly. The non-specific clinical features of B12 deficiency and unreliable serum parameters make diagnosis difficult. We aimed to evaluate the value of oral “beefy red” patches as a clinical marker of B12 deficiency.

Methods

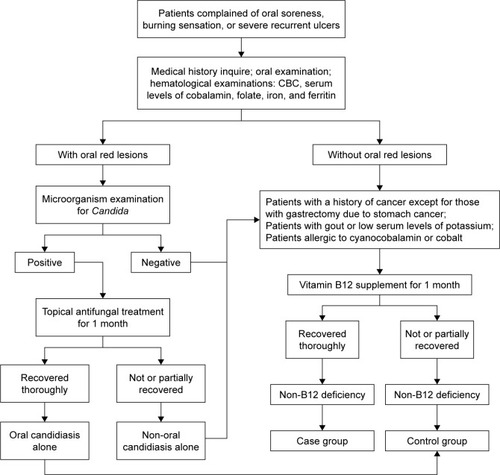

A diagnostic study was conducted in patients complaining of oral soreness, burning sensation, or severe recurrent oral ulcers. Patients underwent clinical examination and laboratory investigations, including complete blood count and estimation of serum B12, folate, iron, and ferritin levels. Resolution of clinical signs and symptoms after 1 month of B12 supplement was regarded as the diagnostic gold standard.

Results

Of 136 patients, 70 had B12 deficiency. Among these patients, the oral “beefy red” patch was observed in 61, abnormal mean corpuscular volume (MCV) was noted in 30, and serum cobalamin levels <200 and <350 pg/mL were seen in 59 and 67 cases, respectively. The “beefy red” patch demonstrated the highest diagnostic validity (Youden index 0.84) and reliability (consistency 91.9% [95% CI: 87.3%–96.5%]), followed by the serum cobalamin levels and MCV. The combination of “beefy red” patch with cobalamin <350 pg/mL exhibited better diagnostic value than the combination of “beefy red” patch with cobalamin <200 pg/mL, with accuracy of 0.81 vs 0.74 and reliability of 90.4% (95% CI: 85.5%–95.4%) vs 86.8% (95% CI: 81.1%–92.5%).

Conclusion

The combination of oral “beefy red” patch and serum cobalamin level <350 pg/mL appears to be useful for diagnosis of B12 deficiency.

Introduction

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is an important coenzyme for DNA synthesis and erythrocyte production and differentiation, and is essential for normal neurological function. B12 deficiency may lead to megaloblastic anemia, epithelial abnormalities in the digestive tract mucosa, and severe neuropsychiatric damage.Citation1 Deficiency is common among the elderly, and the prevalence is known to increase with age. Cobalamin malabsorption is the primary cause of deficiency.Citation2 About 10%–30% of the elderlyCitation3–Citation5 and 30%–41.6% of sick and malnourished patientsCitation6,Citation7 have low serum cobalamin levels. Patients with untreated clinical and subclinical B12 deficiency are at high risk of developing serious neurological disorders such as age-related brain atrophy and degeneration of the funiculi of the spinal cord. Patients with neurological impairment present with paresthesias, ataxia, and cognitive problems.Citation8 Furthermore, the risk of Alzheimer’s disease is doubled in patients with hyperhomocysteinemia, which is partially attributable to low serum levels of cobalamin.Citation9 Early disease recognition and treatment are therefore crucial for prevention of cobalamin deficiency-related central nervous system damage. However, the initial non-specific clinical features of cobalamin deficiency and the insidious progression of the condition make diagnosis difficult, particularly in elderly patients with multiple age-related disorders.Citation10 Although abnormal laboratory results may provide important evidence for confirmation of the disease, the commonly used cutoff for diagnosis of B12 deficiency (serum cobalamin level of <200 pg/mL) has poor sensitivity.Citation11–Citation13 In Carmel and Agrawal’s report, for example, 22%–35% of patients with B12 deficiency (mostly due to pernicious anemia) had normal serum cobalamin levels.Citation12 In such cases, measurements of serum homocysteine (Hcy) and methylmalonic acid (MMA) – by-products of the cobalamin metabolic pathway – are currently recommended for confirming B12 deficiency. However, serum Hcy and MMA have low or questionable specificity; moreover, serum Hcy level is influenced by lifestyle factors (smoking and alcohol or coffee consumption).Citation14,Citation15 These tests are also expensive, and therefore it would be useful to have reliable clinical markers that could be used to identify patients who need further verification with Hcy or MMA determination.

A potentially useful clinical marker is oral mucosal change in B12 deficiency. The oral mucosa is composed of rapidly dividing cells, and is therefore susceptible to cobalamin deficiency-related disorders in DNA synthesis. The resulting changes in cell structure and the epithelial keratinization patternCitation16 precede some systemic symptoms.Citation17 Hunter’s glossitis, a well-known oral feature of B12 deficiency, presents as diffuse bright red patches (“beefy red” patches) initially and gradually progresses to atrophic glossitis.Citation18 Lesions primarily occur on the dorsal and ventral surfaces and the margin of the tongue. The palatal, buccal, and labial mucosa may also be affected, with lesions presenting as areas of linear, band-like, or irregular erythema.Citation16,Citation19,Citation20

Only a few studies have focused on the value of the oral “beefy red” patch as an indicator of B12 deficiency. In the present study, we aimed to assess the validity and reliability of the oral “beefy red” patch as a clinical marker of B12 deficiency.

Methods

Participants

A diagnostic study was consecutively conducted among 143 adult patients (≥18 years) with complaints of oral soreness, burning sensation, or persistent severe recurrent oral ulcers over the past 6 months who were recruited from among the outpatients visiting the Department of Oral Medicine, Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology during 2012 and 2014. Individuals with a history of cancer (except those who had undergone gastrectomy for stomach cancer), gout, low serum potassium, or allergy to cyanocobalamin or cobalt were excluded.

All participants signed informed consent prior to inclusion in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology (PKUSSIRB-2012100409).

Procedures

Detailed medical history was recorded, including main complaints, general health condition, past medical history, and family history. Oral evaluation was performed by two clinicians who were trained by the principal investigator (HH). The presence of the oral “beefy red” patch was the main sign assessed.

All participants underwent laboratory investigations at an assigned clinical biochemical laboratory; the tests included complete blood count and estimation of serum levels of cobalamin, folate, iron, and ferritin. To confirm oral candidiasis, microorganism examinations (smear or salivary culture for Candida) were also carried out among the patients with oral red lesions. Candida-positive patients were prescribed a topical antifungal agent (nystatin) for 1 month, after which they were reassessed. Those who had complete resolution of symptoms and signs were diagnosed as having oral candidiasis alone and were assigned to the control group. Otherwise, the patients were regarded as having non-oral candidiasis disease or oral candidiasis combined with other diseases. To determine the real B12 deficiency, all subjects enrolled except for those with oral candidiasis alone were administered cobalamin supplements for 1 month. The patients who had complete resolution of clinical signs and symptoms were diagnosed as having had B12 deficiency and were assigned to the case group. The other patients were assigned to the control group, and further examinations (biopsy, immunological tests, and trace elements examination, if necessary) were conducted for their definitive diagnosis ().

In general, the daily requirement for cobalamin in adult is 2 µg. Most excessive cobalamin is stored in the liver with about 4,000–5,000 µg.Citation21 According to the US Institute of Medicine, 100 µg of daily cobalamin supplement is recommended to those over 50 years of age to maintain cobalamin levels, and no tolerable upper intake levels of cobalamin is set.Citation22 Therefore, following the above mentioned rules and based on the findings of previous study,Citation19 the subjects were administered a daily intramuscular injection of 500 µg cyanocobalamin for 1 month. The oral condition of each case was reassessed at the 1-month follow-up. The normalization of both clinical signs and symptoms by cobalamin administration was regarded as the gold standard diagnostic criteria for B12 deficiency. Participants were advised to stop cobalamin supplements and consult their doctors immediately in case of side effects such as diarrhea or allergic symptoms such as hives or rash on any part of the body, swelling of the face, mouth or throat, shortness of breath, or wheezing.

Differential diagnosis of oral “beefy red” patch

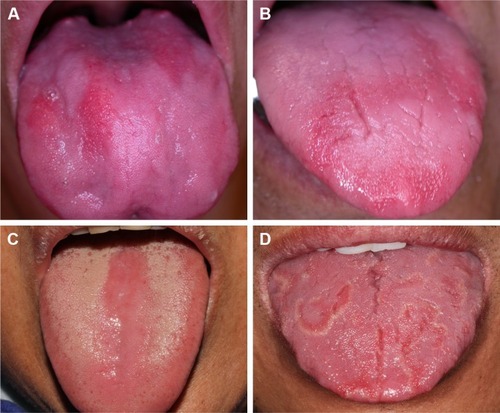

The oral “beefy red” patch was evaluated and identified by two clinicians who were trained by the principal investigator (HH). The “beefy red” patch in B12 deficiency is often confused with other oral red lesions (). shows the differential diagnoses and the characteristic features of each condition.Citation16,Citation19,Citation20,Citation23,Citation24

Figure 2 Different oral manifestations of B12 deficiency and other conditions.

Table 1 Oral manifestations of B12 deficiency and conditions with similar features

Statistical analysis

The sample size yielding a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 80% was estimated, with a relative error (Δ) of 5%–10%. Based on the formula (N = Uα2 P (1 – P)/Δ2), 62–246 patients would be required for the case or control group, with an alpha value of 0.05. Parametric statistical tests were used to analyze the data. The independent samples t-test and the chi-squared test were used to analyze the differences between groups with regard to age and gender, respectively. Sensitivity, specificity, and consistency were used to describe the diagnostic value of the clinical and laboratory parameters. SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 143 patients were initially enrolled; however, 7 patients withdrew from the study due to personal reasons, and thus 136 patients were included in the final analysis. Of these 136 patients, 6 patients were diagnosed with oral candidiasis alone and were classified into the control group. The remaining 130 patients received cobalamin supplementation, as daily cobalamin supplement is recommended to those over 50 years of age and no tolerable upper intake levels of cobalamin is set by the US Institute of Medicine.Citation22 None of the patients experienced any adverse effects due to the cobalamin supplementation. Among the 130 patients, 70 responded well to cobalamin supplement and were therefore identified as having B12 deficiency and classified into the case group. The other 60 patients did not respond to cobalamin supplementation and were assigned to the control group. Thus, there were a total of 66 patients in the control group. Burning mouth syndrome (50/66) was the major diagnosis in the control group, followed by oral candidiasis alone (6/66), recurrent aphthous stomatitis (4/66), and geographic tongue (4/66). Other 2 patients were unidentified, in which the “beefy red” patches continued in spite of cobalamin replacement ().

Table 2 Oral diseases in the control group patients

Mean patient age was 61.7 years (range, 34–84 years) in the case group vs 58.7 years (range, 38–82 years) in the control group (P = 0.06). The proportion of female patients was higher than that of male patients in both groups. Gender distribution was comparable between the two groups (P = 0.55; ).

Table 3 Demographic data of the subjects

The presence of multiple “beefy red” patches (beefy) was the main clinical feature in the case group and was observed in 61 of 70 patients; only 2 such cases (the unidentified cases) were noted in the control group. Thus, the sensitivity (Se-beefy) and specificity (Sp-beefy) of this feature for identification of B12 deficiency were 87.1% and 97.0%, respectively, and the Youden index (r) was 0.84. shows the diagnostic accuracy of the other clinical parameters currently used for diagnosis of B12 deficiency; these include mean corpuscular volume (MCV) >100 fL, serum cobalamin <200 pg/mL (B200), and serum cobalamin <350 pg/mL (B350). MCV >100 fL was noted in 30 patients in the case group vs 0 patients in the control group; thus, the Se-MCV was only 40% and the r-MCV was 0.4; the Sp-MCV was 100%. Serum cobalamin <200 pg/mL (B200) was observed in 59 patients in the case group; the other 11 patients in the case group had serum cobalamin >200 pg/mL (range, 204–375 pg/mL). In comparison, only 4 patients in the control group had serum cobalamin <200 pg/mL (range, 191–197 pg/mL). Thus, the Se-B200 and Sp-B200 values were 84.3% and 93.9%, respectively, and the r-B200 was 0.78. We also examined how the diagnostic value of B12 was affected when serum cobalamin <350 pg/mL was taken as the diagnostic cutoff, as has been recommended by some researchers.Citation25 A total of 67 patients in the case group had cobalamin levels <350 pg/mL; the other 3 patients in the case group had cobalamin levels >350 pg/mL (range, 360–374 pg/mL). In comparison, 16 patients in the control group had cobalamin levels <350 pg/mL (range, 191–347 pg/mL). Thus, the sensitivity, specificity, and Youden index changed to 95.7%, 75.8%, and 0.72, respectively. In combination with the “beefy red” patch, the sensitivities of the serum cobalamin values decreased. The Se-B200 decreased from 84.3% to 75.7%, and the Se-B350 decreased from 95.7% to 84.3%. However, the specificities improved markedly: Sp-B200 increased from 93.9% to 98.5%, and Sp-B350 increased from 75.8% to 97.0%. A parallel increase in r-B350 was also noted, from 0.72 to 0.81; however, r-B200 remained essentially unchanged (0.78 vs 0.74; ). These results suggest that the presence of an oral “beefy red” patch has greater accuracy than MCV and other serological parameters for diagnosis of B12 deficiency. Furthermore, the combination of “beefy red” patch and serum cobalamin <350 pg/mL had greater diagnostic accuracy than the combination of “beefy red” patch with serum cobalamin <200 pg/mL; however, the accuracy was slightly lower than that of “beefy red” patch alone ().

Table 4 Values of various clinical and serum indices for diagnosis of B12 deficiency

With regard to the diagnostic reliability, “beefy red” patch demonstrated the highest consistency of 91.9% (95% CI, 87.3%–96.5%); this was followed by the combination of “beefy red” patch with cobalamin <350 pg/mL (90.4% [95% CI, 85.5%–95.4%]) and serum cobalamin <200 pg/mL alone (89.0% [95% CI: 83.8%–94.3%]). The MCV value was relatively unreliable, with a low consistency of 70.6% (95% CI: 62.9%–78.3%; ).

Discussion

Cobalamin is mainly derived from animal protein and is released via the action of pepsin and hydrochloric acid in the stomach. In the duodenum, free cobalamin binds to intrinsic factor secreted by gastric parietal cells and is finally absorbed by mucosal cells in the terminal ileum.Citation10,Citation26 Problems anywhere in the metabolic pathway could increase the risk of B12 deficiency. Inadequate dietary intake; ileal malabsorption of cobalamin; decreased secretion of intrinsic factor; and prolonged exposure to drugs such as histamine-2 blockers, metformin, and proton pump inhibitors all increase the risk of B12 deficiency.Citation27

Cobalamin is essential for DNA synthesis. The lack of cobalamin prevents red blood cell division in the marrow and leads to increase in cell size,Citation17,Citation28,Citation29 resulting in elevation of the hematological parameter of MCV. Hence, MCV >100 fL (macrocytosis) is often used as a measure for B12 deficiency and even megaloblastic anemia. However, in previous surveys, normal MCV values have been demonstrated in 48%–70% of patients with B12 deficiencyCitation30,Citation31 and even 17%–21% patients with megaloblastic anemia.Citation32,Citation33 Consistent with these previous results, only 42.9% of the B12-deficient patients in the present study exhibited macrocytosis; the sensitivity of MCV for B12 deficiency was as low as 40%. Thus, absence of macrocytosis does not necessarily indicate a normal serum cobalamin level. In the present study, the presence of the oral “beefy red” patch was more accurate and reliable for diagnosis of B12 deficiency, with sensitivity of 87.1%, specificity of 97.0%, and consistency of 91.9% (95% CI: 87.3%–96.5%). The usefulness of these oral lesions for diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency may be attributable to the rapid division of oral mucosal epithelial cells. Rapid regeneration of cells means that B12 deficiency-induced disorders of DNA synthesis are likely to manifest earlier than in other tissues. Changes in cell structure and the epithelial keratinization patternCitation16 lead to formation of atrophic stratified squamous epithelium, which appears as erythematous macules on clinical examination.Citation20 The evidence from this study suggest that the oral “beefy red” patch is a better clinical marker of B12 deficiency than the MCV value. However, there is so far no evidence to suggest that the size of the oral “beefy red” patch is correlated to the severity of B12 deficiency. Quantitative estimation of the oral “beefy red” lesion and examination of its relationship with disease severity may be an important direction for future research.

In this study, a serum cobalamin level of 200 pg/mL was initially defined as the cutoff point for diagnosis of B12 deficiency; this value is still used in many clinical laboratories. However, its accuracy remains controversial due to the high rate of false-negative results.Citation11–Citation13 Based on the benefits of cobalamin supplementation among patients with cobalamin levels between 200 and 350 pg/mL, some researchers have recommended the use of 350 pg/mL as the cutoff value.Citation11 When we used this cutoff instead of 200 pg/mL, we observed an increase in sensitivity (from 84.3% to 95.7%); however, the specificity decreased (from 93.9% to 75.8%). This indicates that ~25% of the patients will be misdiagnosed as B12 deficient if the cutoff point of cobalamin was <350 pg/mL. The use of automated analysis of cobalamin levels may have been responsible for the false-positive results. In the serological assay, cobalamin is designed to bind competitively with a reagent intrinsic factor, prior to which anti-intrinsic factor antibodies are removed from the blood sample.Citation12,Citation13 However, in the automated assay, it is not possible to exclude interference by the intrinsic factor.Citation34,Citation35

In comparison to serological values, the oral “beefy red” patch appears to be a more feasible clinical marker, with higher validity (Youden index of 0.84) and higher consistency (91.9%; 95% CI: 87.3%–96.5%).

However, the oral “beefy red” patch is often confused with other red lesions on the oral mucosa such as geographic tongue and erythematous candidiasis. To avoid the subjective error resulting from clinical differentiation, the oral mucosal changes were combined with serological parameters such as cobalamin <200 pg/mL and cobalamin <350 pg/mL in the present assessment. The combination of oral “beefy red” patch with cobalamin <350 pg/mL was found to be more valid and reliable than the combination of “beefy red” patch with cobalamin <200 pg/mL. In fact, the combination of “beefy red” patch with cobalamin <350 pg/mL had similar diagnostic accuracy as “beefy red” patch alone.

This study has some limitations. Patients with sub-clinical B12 deficiency may be asymptomatic. However, all participants in the present investigation were symptomatic; we included only patients who complained of oral soreness, burning sensation, or recurrent ulcers (common presentations of B12 deficiency). This might have resulted in overestimation of the value of the “beefy red” patch in the diagnosis of B12 deficiency.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results suggest that the oral “beefy red” patch could be useful for diagnosis of B12 deficiency, particularly when used in combination with a cutoff serum cobalamin level of <350 pg/mL. Thus, physicians should pay special attention to oral manifestations during medical history taking and physical examination in high-risk populations such as the elderly, vegetarians, and patients with digestive problems or prolonged exposure to drugs that could cause B12 malabsorption.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GröberUKistersKSchmidtJNeuroenhancement with vitamin B12-underestimated neurological significanceNutrients20135125031504524352086

- AndrèsELoukiliNHNoelEVitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency in elderly patientsCMAJ2004171325125915289425

- AllenLHHow common is vitamin B-12 deficiency?Am J Clin Nutr2009892693S696S19116323

- HerrmannWObeidRSchorrHGeiselJThe usefulness of holotrans-cobalamin in predicting vitamin B12 status in different clinical settingsCurr Drug Metab200561475315720207

- Oliveira MartinhoKLuiz Araújo TinôcoAQueiroz RibeiroAPrevalence and factors associated with vitamin B12 deficiency in elderly from Viçosa/MG, BrasilNutr Hosp20153252162216826545673

- van AsseltDZBlomHJZuiderentRClinical significance of low cobalamin levels in older hospital patientsNeth J Med2000572414910924940

- MézièreAAudureauEVairellesSB12 deficiency increases with age in hospitalized patients: a study on 14,904 samplesJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci201469121576158525063081

- SethiNKRobilottiESadanYNeurological manifestations of Vitamin B12 deficiencyInternet J Nutr Wellness20052112

- SeshadriSBeiserASelhubJPlasma homocysteine as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s diseaseN Engl J Med2002346747648311844848

- AndrèsEVogelTFedericiLZimmerJKaltenbachGUpdate on oral cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12) treatment in elderly patientsDrugs Aging2008251192793218947260

- ClarkeRRefsumHBirksJScreening for vitamin B-12 and folate deficiency in older personsAm J Clin Nutr20037751241124712716678

- CarmelRAgrawalYPFailures of cobalamin assays in pernicious anemiaN Engl J Med2012367438538622830482

- YangDTCookRJSpurious elevations of vitamin B12 with pernicious anemiaN Engl J Med2012366181742174322551146

- Health Quality OntarioVitamin B12 and cognitive function: an evidence-based analysisOnt Health Technol Assess Ser20131323145 eCollection 2013

- GanjiVKafaiMRThird National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyDemographic, health, lifestyle, and blood vitamin determinants of serum total homocysteine concentrations in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994Am J Clin Nutr200377482683312663279

- PontesHANetoNCFerreiraKBOral manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency: a case reportJ Can Dent Assoc200975753353719744365

- DerossiSSRaghavendraSAnemiaOral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod200395213114112582350

- Pétavy-CatalaCFontèsVGironetNHüttenbergerBLoretteGVaillantLClinical manifestations of the mouth revealing Vitamin B12 deficiency before the onset of anemiaAnn Dermatol Venereol20031302 Pt 1191194 French [with English abstract]12671582

- GraellsJOjedaRMMuniesaCGonzalezJSaavedraJGlossitis with linear lesions: an early sign of vitamin B12 deficiencyJ Am Acad Dermatol200960349850019231648

- FloresILSantos-SilvaARColettaRDVargasPALopesMAWidespread red oral lesionsJ Am Dent Assoc2013144111257126024177404

- ChanarinIHistorical review: a history of pernicious anaemiaBr J Haematol2000111240741511122079

- Institute of MedicineDietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and CholineWashington, DCThe National Academies Press1998340342

- SamaranayakeLEssential Microbiology for DentistryEdinburghChurchill Livingstone/Elsevier Medicine2012308309

- GoswamiMVermaAVermaMBenign migratory glossitis with fissured tongueJ Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent201230217317522918106

- CarmelRGreenRRosenblattDSWatkinsDUpdate on cobalamin, folate, and homocysteineHematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program2003628114633777

- Abboud LeonCGeorgesPZaeeterWVitamin B12 deficiencyN Engl J Med2013368212041

- LanganRCZawistoskiKJUpdate on vitamin B12 deficiencyAm Fam Physician201183121425143021671542

- AsliniaFMazzaJJYaleSHMegaloblastic anemia and other causes of macrocytosisClin Med Res20064323624116988104

- GreenRDatta MitraAMegaloblastic anemias: nutritional and other causesMed Clin North Am2017101229731728189172

- LindenbaumJRosenbergIHWilsonPWStablerSPAllenRHPrevalence of cobalamin deficiency in the Framingham elderly populationAm J Clin Nutr19946012118017332

- BhatiaPKulkarniJDPaiSAVitamin B12 deficiency in India: mean corpuscular volume is an unreliable screening parameterNatl Med J India201225633636823998863

- SavageDGLindenbaumJStablerSPAllenRHSensitivity of serum methylmalonic acid and total homocysteine determinations for diagnosing cobalamin and folate deficienciesAm J Med19949632392468154512

- KhanduriUSharmaAMegaloblastic anaemia: prevalence and causative factorsNatl Med J India200720417217518085121

- HamiltonMSBlackmoreSLeeAPossible cause of false normal B-12 assaysBMJ20063337569654655

- VlasveldLTvan’t WoutJWMeeuwissenPCastelAHigh measured cobalamin (vitamin B12) concentration attributable to an analytical problem in testing serum from a patient with pernicious anemiaClin Chem2006521157158 discussion 158–15916391338