Abstract

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis and is a considerable burden to patients and health care systems worldwide. Despite its clinical, economic, and social impact, patient persistence and adherence to prescribed urate-lowering therapies (ULT), ranging from 20% to 70%, is considered to be among the poorest of all chronic conditions. The majority of gout patients consequently receive suboptimal benefits of their prescribed pharmacotherapies. As gout is associated with several comorbidities along with an increased risk of premature mortality, achieving improved outcomes through adherence to ULT is crucial. Adherence to medication is complex and multidimensional and includes a combination of treatment-, patient-, and physician-related factors. This review explores the factors related to ULT adherence with the overall aim of helping health care providers better understand the barriers to adherence. Several interventions targeting pharmacists, nurses, and patients are being investigated to improve adherence. Furthermore, enhanced awareness and understanding of the need to treat-to-target in order to improve patient outcomes is needed among health care professionals. Greater understanding of the multidimensional nature of non-adherence can help physicians to treat gout more effectively and empower patients to improve self-management of this long-term disease.

Introduction

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis in the general population and is a considerable burden for both the patient and health care system.Citation1,Citation2 Unfortunately, this burden is likely to worsen due to the increasing prevalence of gout in Western countries. For example, a UK-based study in which the prevalence and incidence of gout was estimated for each calendar year from 1997 to 2012 registered a 63.9% increase in prevalence and a 29.6% increase in incidence over the 15-year period.Citation3 Furthermore, data from the USA show that the prevalence of gout has risen in the recent decades in individuals over the age of 65 years, while it is relatively stable among younger age groups. The increase in prevalence is highest among those over the age of 75 years, where it has increased from ~20 per 1,000 to around 65 per 1,000.Citation1

Gout can be considered to be a systemic disease caused by the accumulation of monosodium urate crystals in tissues that induce inflammation.Citation4 Effective treatment of gout is important, not only to improve the negative impact it has on patient quality of life and use of health care resources,Citation5,Citation6 but also because gout is associated with an increased risk of premature mortality.Citation7,Citation8 The presence of tophi in gout patients has been associated with a greater risk of mortality, largely due to cardiovascular (CV) causes.Citation7 A 2017 study showed that even patients with a duration of gout <10 years are at increased risk of death from both non-CV and CV causes.Citation8 Monosodium urate deposition can occur in tissues when serum urate (sUA) levels exceed 6.8 mg/dL (>405 µmol/L) or even lower in the presence of favorable conditions,Citation9 and may result in gout flares, tophi formation, and structural damage to joints.Citation10 Long-term management of gout is based on maintaining sUA below a target level of 6 mg/dL (<360 µmol/L) to enhance crystal dissolution.Citation11,Citation12

Adherence to prescribed medication is important to the management of chronic diseases, including gout, as obviously long-term drug effectiveness is substantially compromised by patient non-adherence.Citation13 For gout, achieving the optimal therapeutic target of sUA requires concerted efforts to increase adherence to urate-lowering therapies (ULT). However, most studies on the matter have reported very low rates of adherence to ULT among patients with gout. The provision of effective therapy is further limited by the fact that only ~50% of patients with gout are either being consulted for gout or under treatment with ULT.Citation3 Consequently, there is considerable interest in optimizing treatment and management of gout at the patient, community, and national levels. One key intervention is to actively advocating better adherence to ULT.

Defining adherence to therapy

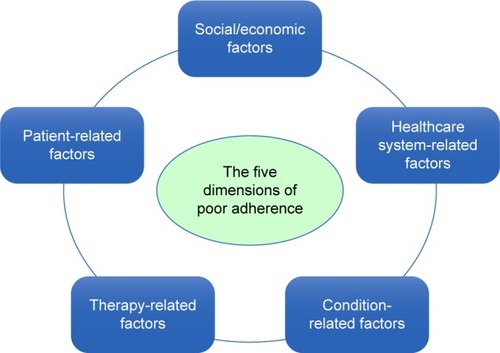

The World Health Organization defines adherence to long-term therapy as “the extent to which a person’s behavior–taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider” ().Citation14 Such a definition places strong emphasis on the patient’s agreement to prescriber recommendations and that patients need to be active partners with health care professionals.Citation15 Non-adherence includes “failing to fill prescriptions, delaying prescription fills, reducing the strength of the dose taken, and reducing the frequency of administration. It can also include the failure to keep appointments or to follow recommended lifestyle or dietary changes.”Citation15

Figure 1 The five dimensions of poor adherence.

Abbreviation: WHO, World Health Organization.

Factors affecting adherence

Measuring adherence to therapy is not necessarily straightforward, and a number of methods, including both indirect and direct approaches, have been proposed (). A common indirect approach involves subjective rating of adherence using patient and prescriber questionnaires. However, such methods are often inaccurate as patients may not report their actions or behavior in relation to adherence objectively, consistently, or correctly.Citation16,Citation17

Table 1 Methods used to measure adherence to gout therapy

The 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale has recently been used to monitor medication adherence, but was found to not be useful in discriminating patients who were or were not achieving the recommended target of sUA; nevertheless, it was able to identify patients who failed to comprehend the need for long-term ULT.Citation18 In such patients, targeted education and support to improve coping mechanisms may be beneficial.

Objective methods, such as counting remaining dosage units, pill counts, and electronic monitoring systems (pharmacy data, medical records, and medication event monitoring system), attempt to overcome some of the limitations of subjective methods, but may be either too expensive for routine use, or may capture incomplete information.Citation19 In this regard, the medication possession ratio, that is, the number of doses filled by the pharmacist divided by the number of days in a predefined period, has been used to quantify adherence to gout therapy.Citation20 Biochemical measurements using nontoxic biological markers is a direct approach to assess adherence behaviors as it can provide more objective evidence that a patient has taken a dose of the medication.Citation21 However, the feasibility of such an approach may limit its practical utility due to variability in diet, absorption, and rate of excretion. Regardless of how adherence to therapy is measured, it is clear that non-adherence remains a major problem to be overcome in the long-term management of many chronic conditions.

Social/economic factors

Social support, including from family, friends, or caregivers, can be an important factor in assisting patients to adhere to medication regimens. Patients with social support often show improved adherence to prescribed treatments. In contrast, negative social/economic factors, such as unstable living environments, lack of adequate access to health care, limited financial resources, high costs of medication, and difficult schedules at work, have been associated with poor adherence.Citation14

The economic costs of increased urate and gout are significant; for 1 year following diagnosis of gout in patients aged >65 years, direct cost associated with either gout or increased sUA levels was US$876 (5.9%) of the total health costs registered in the period (2005); this was mainly related to inpatient care (57.6%). A very high sUA level (≥9 mg/dL) was associated with an additional US$3,103 in regression-adjusted total 12 months all-cause health care costs and US$276 in regression-adjusted 12 months gout-related costs, compared with a low sUA level (<6 mg/dL).Citation6,Citation22 A recent Canadian study of patients with incident gout aged ≥66 years examined their 5-year total health care costs. It reported that patients with gout (CA$44,297) incurred a significantly higher average health care cost compared with gout-free patients (CA$33,965), for an incremental cost of CA$10,332 (95% CI: CA$9,617–CA$11,039; p<0.01).Citation23

Health care system-related factors

The physician–patient relationship is an important aspect related to the health care system that can greatly affect adherence to therapy. It is obvious that empathy between the prescriber and the patient can encourage the patient, aiding increased adherence to treatment. At the same time, lack of communication on the benefits and need for treatment, as well as precise instructions on taking the medication and its adverse events, can negatively influence adherence. It is also clear that costs, reimbursement issues or lack thereof, as well as prescriber incentives in some settings may greatly impact adherence.Citation14

Condition-related factors

These are factors associated with illness-related burdens that the patient must face. In many conditions, adherence to treatment often decreases over the long term. This is especially true of conditions, such as well-controlled gout where the patient has few or no symptoms. This reinforces the need for the patient to have adequate knowledge of their condition and the possible consequences if adequate treatment is not provided.Citation14

Therapy-related factors

The most prominent therapy-related factors are linked to the difficulty in adhering to the prescribed treatment regimen and its duration. In addition, failure of previous treatment, as well as repeated changes in the treatment regimen, may be associated with low adherence. Moreover, the possible side effects of therapy must not be overlooked as they cause patients to discontinue their medication or take it in a manner that is not in accordance with that prescribed.Citation14

Patient-related factors

Such factors include knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and expectations that the patient has toward a particular therapy. If patients lack knowledge about the disease and why adequate treatment is needed, they may have poor medication adherence.Citation24 Similarly, a perceived lack of interest in treatment of the condition and substance abuse may be related to reduced adherence to therapy.Citation25 Forgetfulness, psychological anxiety, possible adverse effects of medication, and negative concerns about the perceived efficacy of treatment can also influence treatment adherence.Citation14

Patient-related non-adherence may be non-intentional or intentional. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence defines these as follows: “Unintentional non-adherence occurs when the patient wants to follow the agreed treatment but is prevented from doing so by barriers that are beyond their control. Intentional non-adherence occurs when the patient decides not to follow the treatment recommendations.”Citation26 Unintentional non-adherence involves aspects, such as the lack of capacity or resources, for example, when patients have not understood prescribing instructions and/or the consequences of not taking their medication, when they cannot afford co-payment costs, or whenever they find it difficult to schedule, administer, or remember to take their treatment. Intentional non-adherence involves an unwillingness to take a medication based on the person’s perceptions of that treatment and their lack of motivation or desire to initiate and continue it. In some patients, psychiatric issues, such as depression, cognitive restraints, low or lacking office visits, and a poor relationship with the prescriber, may also contribute to greater non-adherence to therapy. Prescribers thus need to have a better understanding of patient-related factors that can dispose to either intentional or unintentional non-adherence and attempt to overcome these barrier to adherence.

Adherence in other chronic diseases

Good adherence is most commonly defined as the percentage of patients who take at least 80% of their prescribed medication, although this cutoff value may be up to 90% in some investigations.Citation27 Unfortunately, poor adherence is a primary reason for the suboptimal clinical benefits of pharmacotherapy in many diseases.Citation28 In general, adherence is believed to be highest in the management of human immunodeficiency virus infection and cancer, indicating that disease seriousness is a major motivating factor for patients to take their medication as prescribed.Citation29 While it is sensible to presume that more seriously ill patients would be more adherent to medication, at least 1 study has reported that patients with cancer on long-term oral treatment exhibit non-adherence comparable with that of the general patient population.Citation30 Treatment adherence rates and related issues in several diseases are briefly overviewed below by way of example.

Non-adherence to treatment for hypertension is a well-documented cause of poor control of blood pressure and development of “pseudo-resistant” hypertension. Published estimates of the prevalence to antihypertensive therapy vary widely, with rates of non-adherence ranging from 3% to up to 65%,Citation31 using biochemical screening, 25% of patients are either totally or partially non-adherent to treatment.Citation32 Unsurprisingly, the highest prevalence of partial and total non-adherence was among patients who had inadequate control of hypertension.Citation33

In type 2 diabetes, despite the well-known benefits of targeted antihyperglycemic therapy on organ damage and mortality, recommended targets are achieved by <50% of patients and are frequently associated with suboptimal adherence.Citation27,Citation34 As for other pathologies, the reasons for non-adherence are multifactorial and include patient age, perception and duration of disease, complexity of therapeutic regimen, psychological comorbidities and tolerability, and cost of treatment.Citation27

In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), adherence ranges from 50% to 80%.Citation19 Patients appear to be more adherent to biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and parenteral administration, in contrast to oral and nonbiological DMARDs. Patient education programs (eg, self-efficacy strategies, information about RA therapy, and strategies for coping) have been shown to increase adherence to therapy.Citation25

Adherence in gout

A number of methods have been used to assess adherence in gout, including electronic prescription records, self-reporting measures, and laboratory results.Citation35 However, regardless of the method used to measure adherence, it is unequivocal that medication adherence is suboptimal and remains a therapeutic challenge. Overall, adherence rates vary widely, from 20% to 70%,Citation19 and are possibly among the worst for any medication for chronic disease. Adherence during the first year of drug therapy in seven chronic conditions, including hypertension (72.3%), hypothyroidism (68.4%), diabetes mellitus (65.4%), seizure disorders (60.8%), hypercholesterolemia (54.6%), and osteoporosis (51.2%), were all better than for gout (36.8%).Citation12

A systematic review showed that less than half of patients (10%–46%) appeared adherent to ULT.Citation35 In a large study of 4,166 patients initiating ULT, over half (56%) were non-adherent; predictors for non-adherence included age <45 years, fewer comorbidities, no previous office visits for gout before ULT initiation, and prior administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents within the last year.Citation36

Studies worldwide have confirmed that adherence to ULT is low (). A study using a large primary care database in the UK (the Clinical Practice Research Datalink [CPRD]) with health information on ~8% of the general population, 61% of patients were found to be either non-adherent (18%) or partially adherent (43%) to ULT.Citation14 Similar results have been reported using a pharmacy claims database in Ireland, where 45.5% and 35.3% of patients initiating ULT were adherent at 6 and 12 months, respectively.Citation20 In addition, a large retrospective study in Israel showed that only 17% were adherent to allopurinol,Citation37 while in Italy, only 3.2% of patients remained adherent to allopurinol after 1 year.Citation38 In a gout-oriented rheumatology practice in Australia, failing to reach target sUA was almost always due to non-adherence.Citation39 Finally, a recent population-based cohort study from Sweden of 7,709 gout patients confirmed that long-term adherence was poor.Citation40 Within 1 year after first diagnosis of gout, only 32% of patients had received ULT. Moreover, of those initiating ULT, 75% did not persist with the treatment during the first 2 years. The study also reported that age <50 years and lack of comorbidities were associated with non-persistence to ULT.

Table 2 Summary of studies worldwide on adherence to ULT

Barriers to adherence in gout

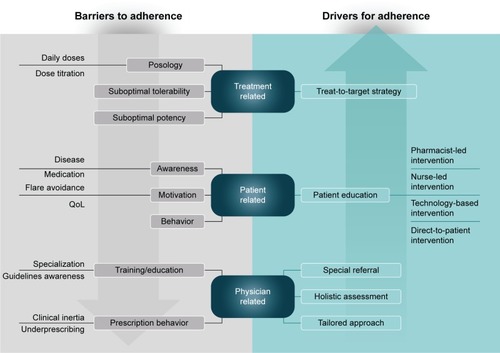

Improving adherence to ULT requires overcoming treatment-, patient-, and physician-related barriers. These are depicted in .

Figure 2 Barriers and facilitators of adherence to chronic gout medications.

Treatment-related factors

There are several treatment-related factors that affect adherence, including posology, tolerability, and potency. With regard to posology, once-daily ULT (such as febuxostat, benzbromarone, or lesinurad) would likely be favored by patients over those that require multiple daily doses as in the case of probenecid and allopurinol (if prescribed at >300 mg/day), which may thus promote greater adherence. In addition, continual dose adjustment required for some ULT to achieve the desired clinical effect may be a painstaking process that discourages adherence. It is clear that ULT that are better tolerated will likely be associated with improved adherence to therapy.

Physicians should also consider that the relative potency of ULT may be a risk of inducing gout flares, which may represent a limitation in terms of adherence. This is relevant since some studies have suggested that poor adherence to ULT may be associated with the risk of acute gout flares when initiating therapy, as well as with poor response, continued attacks of acute gout, suboptimal dosing, and intolerance to allopurinol.Citation20 Accordingly, education and information on the risk of initial flares and implementation of adequate measures, such as prophylaxis and early control of acute inflammation, may be useful to avoid discontinuation of ULT.

Adherence to ULT, considering both allopurinol and febuxostat, has been studied in the large, real-life observational study, CACTUS, involving 3,079 patients with gout.Citation41 Appropriate adherence was observed in 92% and 82% of patients on febuxostat and allopurinol, respectively. Intervention was likely associated with the increase in adherence, which can be considered adequate with both medications.

Patient-related factors

One of the most important patient-related factors is the lack of understanding by health care providers, and as a consequence, gout can become chronic in patients if left untreated/undertreated.Citation42 Some patients may view gout attacks as being only inconvenient and that they have no adverse effects on their overall health, and thus seek only pain relief and dietary control.Citation42 However, taking a medication requires patients to fill prescriptions for a prescribed medication and to understand how to take the medication; they also need the knowledge of how the medication fits into overall disease management.Citation43

Additional barriers include concerns about cost and side effects of therapy, forgetfulness, the belief that gout did not warrant any long-term treatment and doubts about its effectiveness, pill size and difficulty in swallowing, and a lack of adequate information.Citation44–Citation46 Undoubtedly, at least in some settings, financial concerns may be related to non-adherence as patients must obviously have the resources to pay for their medication, in addition to the motivation and self-management skills to take it on a regular basis.

Prescription of ULT from a nonspecialist, compared with rheumatologists or nephrologists, is also a predictor of poor adherence.Citation47 It may be that if patients are not made aware of the risk of gout flares, a subsequent flare may lead to greater non-adherence. Patients should thus be clearly instructed that lowering sUA levels to target is the only means of avoiding future risk of gout flares, which may, therefore, be a major motivating factor to adhere to therapy.

Overcoming patient-related barriers to better adherence also requires identification of motivators for persisting on therapy, including the prevention of both gout flares and pain.Citation45 Furthermore, patients may report that ULT gives them the opportunity to eat certain preferred foods in moderation without flares, and that integrating ULT into their everyday routine was a successful approach.Citation45 The latter is important as it would help to minimize non-intentional adherence. Accordingly, improving patient self-management skills while providing patient education would appear to be two critical areas of intervention.

Physician-related factors

The CPRD link study in the UK demonstrated that not only was patient adherence to therapy low, but ULT agents were also underprescribed.Citation3 Among prevalent gout patients, only 49% were being consulted explicitly for gout or treated with ULT; of these, 38% received ULT. In addition, only 18.6% of incident gout patients were receiving ULT within 6 months of diagnosis, which increased to 27.3% at 12 months. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile highlighting that even in the UK, the prescription rate for ULT is highly variable in different settings, ranging from 0% to 100%.Citation48 This failure to initiate or intensify therapy according to evidence-based guidelines is increasingly being acknowledged as a phenomenon that contributes to inadequate management of chronic conditions and is referred to as clinical inertia.

Physicians often complain that they are unfamiliar with both current guidelines and management of gout;Citation49 they do not usually aim for a specific sUA target or regularly monitor levels of sUA,Citation50 and prescribe standard doses of medication instead of tailored prescriptions, which may not be adequate for a number of patients.Citation51

Quality of care indicators are the important quality improvement initiatives for guiding physicians in the clinical care and management of patients with gout.Citation52 However, in a UK-based study of physician adherence, one-quarter to one-half of all patients eligible for at least one of the validated quality of care indicators were subject to possible prescribing error, suggesting that inappropriate prescribing practices are widespread in patients with gout.Citation53 A study undertaken in general practitioners identified specific knowledge gaps and discrepancies between illness perceptions and stated clinical practice behavior that may compromise patient management in primary health care.Citation54 Accordingly, both holistic assessment and patient education are fundamental to addressing individual risk factors that can help to improve adherence to therapy. Undoubtedly, greater physician education is needed to reach this goal. It must be realized that in some settings, due to cost considerations, physicians may have prescribing limitations in terms of choice of drug and that patients have difficulty in accessing health care, limiting the ability of prescribers to treat patients.

Overcoming the barriers to better adherence to ULT

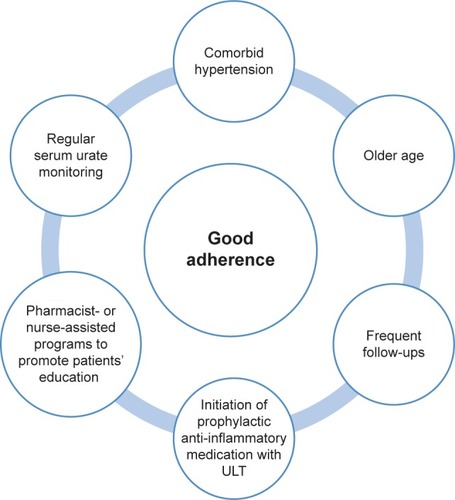

Several types of interventions have been investigated for their potential to improve adherence to ULT. It should be emphasized that both a treat-to-target strategy and the European League Against Rheumatism have considered patient education to be an overarching principle of gout therapy.Citation11,Citation12 It is thus crucial that health care providers inform and properly educate patients to enhance adherence. outlines the factors identified as associated with good adherence in patients using ULT for gout.

Figure 3 Factors identified as associated with good adherence in patients using ULT for gout.

Pharmacist-based interventions

Goldfien et al presented the results of a pilot study examining the efficacy of a pharmacist-based, telephone-driven program, including educational materials in which sUA of at least 6 mg/dL was achieved and maintained in >80% of subjects.Citation55 The benefits of pharmacist-led care are being further investigated in the Randomized Evaluation of an Ambulatory Care Pharmacist-Led Intervention to Optimize Urate Lowering Pathways study, wherein gout patients newly initiating allopurinol are being randomized to either pharmacist-led intervention or usual care.Citation56

Nurse-based interventions

Nurse-delivered intervention has also been successfully used to show that patients can successfully meet treatment goals.Citation57 After showing a positive effect (ie, >90% of patients at sUA target) in a proof of concept study,Citation57 the effectiveness of nurse-led intervention in the long term was further confirmed by Abhishek et al.Citation24 The study investigators evaluated the persistence and adherence to ULT in primary care at 5 years after an initial nurse-led treatment of gout in 100 patients. In the 75 patients who returned completed questionnaires, the 5-year persistence to ULT was 90.7%; of those with sUA measurements available, the mean level was 292.8 µmol/L (4.93 mg/dL). These results suggest that initial treatment combined with individualized patient education and involvement in treatment decisions results in excellent adherence to ULT.

Patient-targeted interventions

In 2013, an analysis of gout patient education resources concluded that critical information on prophylaxis of acute flares during ULT initiation and titration, and treating sUA to target, was not present in at least 60% of patient-targeted materials.Citation58 Moreover, about one-third of materials were above the average reading level of rheumatology patients. Fields et al published the results of a multidisciplinary patient education and monitoring program for gout patients.Citation59 After 12 months, on a scale of 1 (most) to 5 (least), scores of ≤3 were given by 84.6% of subjects with regard to the usefulness of the overall program in understanding and managing gout. Thus, patient education programs can be considered to be effective in increasing patients’ knowledge of the disease. However, much work remains to provide patients with adequate resources that can positively influence adherence to therapy.

Technology-based interventions

Given the increasing reliance and utilization of mobile devices and the Internet, a self-management eTool has recently been proposed with a number of potentially useful characteristics, such as education, monitoring sUA, and reminders for medication.Citation60 Such tools will certainly provide valuable resources for a selected group of patients. Finally, a number of mobile applications are available that may aid in the management of gout.Citation61 However, at present, there is only one app that includes all current recommendations to assist in patient self-management, even if some features must be activated manually.Citation61 The development of specific mobile apps, therefore, represents another area that can help to empower successful self-management of gout, even if underdeveloped at present.

Conclusion

Gout is becoming more prevalent and is associated with an increased number of comorbidities and risk of premature mortality. Given that well-tolerated and highly effective treatments are available, they should be properly prescribed. ULT are currently underprescribed and are associated with poor patient adherence, which is considered to be predominantly due to lack of patient education by the prescribing physician,Citation51 as well as misconceptions about treatment expectations, targets, and outcomes. While many efforts to improve adherence have been centered on patient education and support using a variety of approaches,Citation62 health care professionals also need to be aware that both patient and physician education are needed to bridge existing gaps and improve patient outcomes through better adherence to treatment.

Author contributions

Both authors have substantially contributed to conception and design of the paper, drafted and revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version for submission, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgments

The authors have received editorial assistance from Argon Healthcare International. Editorial assistance was supported by Menarini International Operations Luxemburg S.A.

Disclosure

FPR has received fees as advisor or speaker from Grünenthal, Menarini, and Spanish Foundation for Rheumatology, and investigation grants from Spanish Foundation for Rheumatology and Cruces Rheumatology Association. GD received fees as an advisor or speaker for Menarini. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- RoddyEZhangWDohertyMThe changing epidemiology of goutNat Clin Pract Rheumatol20073844344917664951

- SmithEHoyDCrossMThe global burden of gout: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 studyAnn Rheum Dis20147381470147624590182

- KuoCFGraingeMJMallenCZhangWDohertyMRising burden of gout in the UK but continuing suboptimal management: a nationwide population studyAnn Rheum Dis201574466166724431399

- WheltonAMacdonaldPAZhaoLHuntBGunawardhanaLRenal function in gout: long-term treatment effects of febuxostatJ Clin Rheumatol201117171321169856

- KhannaPPNukiGBardinTTophi and frequent gout flares are associated with impairments to quality of life, productivity, and increased healthcare resource use: results from a cross-sectional surveyHealth Qual Life Outcomes20121011722999027

- TriesteLPallaIFuscoFThe economic impact of gout: a systematic literature reviewClin Exp Rheumatol2012304 Suppl 73S145S14823072897

- Perez-RuizFMartinez-IndartLCarmonaLHerrero-BeitesAMPijoanJIKrishnanETophaceous gout and high level of hyperuricaemia are both associated with increased risk of mortality in patients with goutAnn Rheum Dis201473117718223313809

- VincentZLGambleGHouseMPredictors of mortality in people with recent-onset gout: a prospective observational studyJ Rheumatol201744336837327980010

- DesideriGCastaldoGLombardiAIs it time to revise the normal range of serum uric acid levels?Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci20141891295130624867507

- TauscheAKJansenTLSchroderHEBornsteinSRAringerMMüller-LadnerUGout–current diagnosis and treatmentDtsch Arztebl Int200910634–3554955519795010

- KiltzUSmolenJBardinTTreat-to-target (T2T) recommendations for goutAnn Rheum Dis201676463263827658678

- RichettePDohertyMPascualE2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of goutAnn Rheum Dis2017761294227457514

- BriesacherBAAndradeSEFouayziHChanKAComparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditionsPharmacotherapy200828443744318363527

- WHOAdherence to long-term therapies. Evidence for action Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en/Accessed April 16, 2018

- HigueraLCarlinCSAndersonSAdherence to disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosisJ Manag Care Spec Pharm201622121394140127882830

- MoriskyDEGreenLWLevineDMConcurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherenceMed Care198624167743945130

- SpectorSLKinsmanRMawhinneyHCompliance of patients with asthma with an experimental aerosolized medication: implications for controlled clinical trialsJ Allergy Clin Immunol1986771 Pt 165703511127

- TanCTengGGChongKJUtility of the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale in gout: a prospective studyPatient Prefer Adherence2016102449245727980395

- de AchavalSSuarez-AlmazorMEImproving treatment adherence in patients with rheumatologic diseaseJ Musculoskelet Med20102710169147624078770

- McGowanBBennettKSilkeCWhelanBAdherence and persistence to urate-lowering therapies in the Irish settingClin Rheumatol201635371572125409858

- VitolinsMZRandCSRappSRRibislPMSevickMAMeasuring adherence to behavioral and medical interventionsControl Clin Trials2000215 Suppl188S194S11018574

- WuEQPatelPAYuAPDisease-related and all-cause health care costs of elderly patients with goutJ Manag Care Pharm200814216417518331118

- FischerACloutierMGoodfieldJBorrelliRMarvinDDziarmagaAThe direct economic burden of gout in an elderly Canadian populationRheumatol201744195101

- AbhishekAJenkinsWLa-CretteJFernandesGDohertyMLong-term persistence and adherence on urate-lowering treatment can be maintained in primary care-5-year follow-up of a proof-of-concept studyRheumatology (Oxford)201756452953328082620

- HillJBirdHJohnsonSEffect of patient education on adherence to drug treatment for rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trialAnn Rheum Dis200160986987511502614

- NICEMedicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherenceClinical guideline CG76 Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg76/resources/medicines-adherence-involving-patients-in-decisions-about-prescribed-medicines-and-supporting-adherence-pdf-975631782085Accessed April 18, 2018

- Garcia-PerezLEAlvarezMDillaTGil-GuillénVOrozco-BeltránDAdherence to therapies in patients with type 2 diabetesDiabetes Ther20134217519423990497

- Dunbar-JacobJErlenJASchlenkEARyanCMSereikaSMDoswellWMAdherence in chronic diseaseAnnu Rev Nurs Res200018489010918932

- HugtenburgJGTimmersLEldersPJVervloetMvan DijkLDefinitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: a challenge for tailored interventionsPatient Prefer Adherence2013767568223874088

- NilssonJLAnderssonKBergkvistABjörkmanIBrismarAMoenJRefill adherence to repeat prescriptions of cancer drugs to ambulatory patientsEur J Cancer Care (Engl)200615323523716882118

- VrijensBVinczeGKristantoPUrquhartJBurnierMAdherence to prescribed antihypertensive drug treatments: longitudinal study of electronically compiled dosing historiesBMJ200833676531114111718480115

- TomaszewskiMWhiteCPatelPHigh rates of non-adherence to antihypertensive treatment revealed by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HP LC-MS/MS) urine analysisHeart20141001185586124694797

- NHLBIPrevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/jnc7full.pdfAccessed April 18, 2018

- CramerJAA systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetesDiabetes Care20042751218122415111553

- De VeraMAMarcotteGRaiSGaloJSBholeVMedication adherence in gout: a systematic reviewArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201466101551155924692321

- HarroldLRAndradeSEBriesacherBAAdherence with urate-lowering therapies for the treatment of goutArthritis Res Ther2009112R4619327147

- Zandman-GoddardGAmitalHShamrayevskyNRazRShalevVChodickGRates of adherence and persistence with allopurinol therapy among gout patients in IsraelRheumatology (Oxford)20135261126113123392592

- MantarroSCapogrosso-SansoneATuccoriMAllopurinol adherence among patients with gout: an Italian general practice database studyInt J Clin Pract201569775776525683693

- CorbettEJPentonyPMcGillNWAchieving serum urate targets in gout: an audit in a gout-oriented rheumatology practiceInt J Rheum Dis201720789489728205336

- DehlinMEkstromEHPetzoldMStrömbergUTelgGJacobssonLTFactors associated with initiation and persistence of urate-lowering therapyArthritis Res Ther2017191628095891

- RichettePFlipoRNPatrikosDKCharacteristics and management of gout patients in Europe: data from a large cohort of patientsEur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci201519463063925753881

- ChiaFLPoorly controlled gout: who is doing poorly?Singapore Med J201657841241427549096

- Nasser-GhodsiNHarroldLROvercoming adherence issues and other barriers to optimal care in goutCurr Opin Rheumatol201527213413825633242

- HarroldLRMazorKMVeltenSOckeneISYoodRAPatients and providers view gout differently: a qualitative studyChronic Illn20106426327120675361

- SinghJAFacilitators and barriers to adherence to urate-lowering therapy in African-Americans with gout: a qualitative studyArthritis Res Ther2014162R8224678765

- SpencerKCarrADohertyMPatient and provider barriers to effective management of gout in general practice: a qualitative studyAnn Rheum Dis20127191490149522440822

- SolomonDHAvornJLevinRBrookhartMAUric acid lowering therapy: prescribing patterns in a large cohort of older adultsAnn Rheum Dis200867560961317728328

- KuoCFGraingeMJMallenCZhangWDohertyMEligibility for and prescription of urate-lowering treatment in patients with incident gout in EnglandJAMA2014312242684268625536262

- VaccherSKannangaraDRBaysariMTBarriers to care in gout: from prescriber to patientJ Rheumatol201643114414926568590

- AnnemansLSpaepenEGaskinMGout in the UK and Germany: prevalence, comorbidities and management in general practice 2000–2005Ann Rheum Dis200867796096617981913

- ReesFHuiMDohertyMOptimizing current treatment of goutNat Rev Rheumatol201410527128324614592

- MikulsTRMacLeanCHOlivieriJQuality of care indicators for gout managementArthritis Rheum200450393794315022337

- MikulsTRFarrarJTBilkerWBFernandesSSaagKGSuboptimal physician adherence to quality indicators for the management of gout and asymptomatic hyperuricaemia: results from the UK General Practice Research Database (GPRD)Rheumatology (Oxford)20054481038104215870145

- SpaetgensBPustjensTScheepersLEJMJanssensHJEMvan der LindenSBoonenAKnowledge, illness perceptions and stated clinical practice behaviour in management of gout: a mixed methods study in general practiceClin Rheumatol20163582053206126898982

- GoldfienRDNgMSYipGEffectiveness of a pharmacist-based gout care management programme in a large integrated health plan: results from a pilot studyBMJ Open201441e003627

- CoburnBWCheethamTCRashidNRationale and design of the randomized evaluation of an Ambulatory Care Pharmacist-Led Intervention to Optimize Urate Lowering Pathways (RAmP-UP) StudyContemp Clin Trials20165010611527449546

- ReesFJenkinsWDohertyMPatients with gout adhere to curative treatment if informed appropriately: proof-of-concept observational studyAnn Rheum Dis201372682683022679303

- RobinsonPCSchumacherHRJrA qualitative and quantitative analysis of the characteristics of gout patient education resourcesClin Rheumatol201332677177823322247

- FieldsTRRifaatAYeeAMPilot study of a multidisciplinary gout patient education and monitoring programSemin Arthritis Rheum201746560160827931979

- FernonANguyenABaysariMDayRA User-centred approach to designing an eTool for gout managementStud Health Technol Inform2016227283327440285

- NguyenADBaysariMTKannangaraDRMobile applications to enhance self-management of goutInt J Med Inform201694677427573313

- AungTMyungGFitzGeraldJDTreatment approaches and adherence to urate-lowering therapy for patients with goutPatient Prefer Adherence20171179580028458524