Abstract

Objectives

The most serious adverse reaction of cisplatin is acute kidney injury (AKI). Cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury (CIA) has no specific preventive measures. This study aims to explore the characteristics and risk factors for CIA in the elderly and to identify potential methods to reduce CIA.

Materials and methods

Patients ≥18 years old, with primary tumors, who received initial cisplatin chemotherapy and whose serum creatinine (SCr) values were measured within 2 weeks pre- and postcisplatin treatment and who had complete medical records, were selected from a single center from January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2015. The exclusion criteria included radiotherapy or surgery, recurrent tumors, previous cisplatin treatment, lack of any SCr values before or after cisplatin therapy, and incomplete medical records.

Results

Out of a total of 527 patients, 349 were elderly. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB) use (9.2%) was more prevalent in the elderly than in younger patients (2.8%, p = 0.007). The dosage of cisplatin treatment was lower in the elderly, but the incidence of CIA (9.46%) was higher in the elderly than in younger patients (3.37%). There were significant differences in the SCr levels, estimated glomerular filtration rate, ACEI/ARB use, and whether a single application of cisplatin was administered, between the elderly AKI group and the non-AKI group. Multivariable analysis showed that administration of a single application of cisplatin (OR 2.853, 95% CI: 1.229, 6.621, p = 0.015) and ACEI/ARB use (OR 3.398, 95% CI: 1.352, 8.545, p = 0.009) were predictive factors for developing CIA in the elderly.

Conclusion

The incidence of CIA in the elderly was higher than in younger patients. ACEI/ ARB usage and administration of a single application of cisplatin were independent risk factors for CIA in the elderly.

Introduction

Medication-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) is significant in the elderly; medications account for ~20% of AKI among older patients.Citation1 The aged population is susceptible to cancer.Citation2 In the USA, most patients diagnosed with cancer are ≥65 years old, and it has been predicted that from 2010 to 2030, the cancer incidence among the aged will increase by 67%.Citation3 Cisplatin is widely used for the treatment of various solid tumors, such as lung, esophageal, bladder, head, and neck cancers.Citation4 Currently, according to the National Institutes of Health, more than 273,000 cancer-related clinical trials are being conducted worldwide, in which the majority of the tested drugs are cisplatin-and platinum-based agents.Citation5 However, cisplatin nephrotoxicity is observed in more than 30% of older patients, and cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury (CIA) is the most serious adverse reaction, which limits its use and efficacy in chemotherapy.Citation6 Moreover, the mechanism of nephrotoxicity remains unclear. Although hydration and forced diuresis with diuretics or mannitol are the best-known and most common nephroprotective measures, other nephroprotective approaches are also being studied; however, the protective effects are not satisfactory.Citation7,Citation8 There is an urgent need for specific nephroprotective strategies to be used during cisplatin chemotherapy. Therefore, to prevent and reduce the incidence of CIA in the elderly, we investigated the characteristics of elderly patients with cisplatin chemotherapy and explored the risk factors for CIA in the elderly.

Materials and methods

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of Chinese PLA General Hospital (S2016-100-01) regarding human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. The ethics committee of the hospital waived the need for written informed consent from the patients because the study was retrospective.

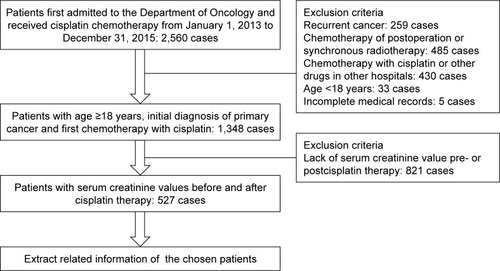

We collected clinical information regarding inpatients in the Department of Oncology using the hospital’s information system: age ≥18 years initially diagnosed with primary cancer and received first cisplatin chemotherapy during the period from January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2015. Patients were excluded if they had undergone synchronous radiation therapy or surgery before cisplatin chemotherapy, were administered cisplatin plus other chemotherapy drugs in other hospitals, were diagnosed with recurrent cancer, or had incomplete medical records. If the patients’ serum creatinine (SCr) levels were not obtained, either pre- or post-cisplatin treatment, they were also excluded. A flowchart demonstrating how patients were screened is shown in . Demographic and treatment data, medical history, and laboratory test data were collected. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated by the four-variable Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation.Citation9,Citation10

CIA was defined as an increase in SCr levels ≥25% from the baseline within 30 days after the first cycle of cisplatinCitation11 or was determined using the AKI 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria for each patient within 7 days after chemotherapy.Citation12 To date, no hydration protocol has been established and followed universally for cancer patients, an no guidelines regarding optimal and minimal fluid volume during cisplatin chemotherapy have been established.Citation13,Citation14 In the current study, if patients received ≥1.5 L intravenous normal saline solution within 1 day before cisplatin treatment, they were considered to have received hydration. Not all patients received oral rehydration.

The quantitative variables are presented as the means ± SD or medians (25%, 75% quartile). Qualitative data are described as n (%). Groups were compared with analysis of variance or Student’s t-test and chi-square test, with continuous or categorical variables, as appropriate. Logistic regression analysis was used to explore the associated risk factors for CIA in the elderly. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Five hundred and twenty-seven patients were chosen for this study, 349 of whom were ≥60 years old. Patients’ demographic and general information are shown in . CIA was observed in 33 (9.46%) of the 349 enrolled elderly patients; however, six (3.37%) of the 178 younger patients were also diagnosed with CIA. The incidence of CIA was significantly higher in the elderly than in the younger group (p = 0.012). In , the baseline characteristics of the older patients showed that the majority of patients were men (79.1%), and the mean age was 61.7 years. Concurrent diseases, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardio-cerebrovascular disease, were more common in the elderly than in younger patients. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB) medication was more frequently used in the older patients (9.2%) than in the younger patients (2.8%, p = 0.007). In terms of laboratory tests, hemoglobin (130.95 vs 133.98 g/L), serum protein (66.18 vs 67.85 g/L), and albumin (38.31 vs 40.69 g/L) levels of the older group were lower than those of the younger group (p<0.05). However, SCr and blood urea nitrogen levels were higher, and the subsequent mean eGFR was lower in the elderly compared with the younger group. The cisplatin total dose and the cisplatin mean dose, according to the body surface area, were smaller for the elderly than for younger patients. Nevertheless, there were no significant differences between the elderly and nonelderly groups in cisplatin frequency, intravenous application, hydration, and diuretic use.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of cancer patients who received cisplatin treatment

Next, the baseline characteristics of older CIA patients were analyzed and compared with those of non-AKI older patients, as shown in . There were significant differences between the two groups only in ACEI/ARB use, the administration of a single cisplatin application, SCr levels, and eGFR. In the AKI group, 21.2% of the patients used ACEI/ARBs, whereas 8.1% used ACEI/ARBs in the non-AKI group (p = 0.014). Of the CIA patients, 59.5% were administered cisplatin once, but only 8.54% received a single cisplatin treatment in the non-AKI group (p = 0.012). The baseline mean SCr level was 74.02 ± 14.96 µmol/L in the AKI group and 65.19 ± 14.99 µmol/L in the non-AKI group (p = 0.001). As a result, the baseline mean eGFRs for the AKI group and the non-AKI group were 86.24 ± 12.21 and 92.71 ± 12.31 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively (p = 0.002).

Table 2 Baseline clinical characteristics of cisplatin-induced AKI in the elderly

In the univariate logistic regression analysis, we identified ACEI/ARB use (OR 3.340, 95% CI: 1.361, 8.192, p = 0.008) and the single administration of cisplatin (OR 3.064, 95% CI: 1.230, 7.632, p = 0.016) as associated predictors of CIA in the elderly (). The baseline eGFR (p = 1.065) and the age of the elderly (p = 0.227) were not significantly associated with CIA. Finally, multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed and revealed that ACEI/ARB use (OR 3.398, 95% CI: 1.352, 8.545, p = 0.009) and the single administration of cisplatin (OR 2.853, 95% CI: 1.229, 6.621, p = 0.015) were independent risk factors for developing CIA in the elderly.

Table 3 Risk factors for cisplatin-induced AKI in the elderly

Discussion

Cisplatin is a nonspecific cytotoxic agent that primarily interferes with cellular DNA replication and the cell cycle, but lacks selectivity. Therefore, it also acts on normal cells and easily causes adverse reactions, especially AKI. However, the exact mechanism of cisplatin nephrotoxicity remains unclear. The traditional preventive methods, such as reducing the drug dosage and administering aggressive hydration, have not been succesful.Citation8,Citation13,Citation14 To date, there are no guidelines for a standardized, simple definition of CIA. A systematic review that included 24 studies showed that the definitions of cisplatin-induced kidney injury varied across studies.Citation15 Therefore, the incidence of CIA in the literature is diverse.

We defined CIA as an increase in the SCr level ≥25% of baseline or used the 2012 KDIGO criteria for the first cisplatin chemotherapy cycle; we opted for this definition for several reasons. First, because of the retrospective nature of this study, it was not easy to obtain values for timed SCr levels and urine volume. Second, Mizuno et al found that the KDIGO criteria could be useful predictors of CIA mortality in patients with different primary cancers,Citation12 and Latcha et al confirmed that an increase in SCr levels ≥25% is not insignificant and is associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) in a long-term follow-up study.Citation11 Third, this criterion ruled out the interference of more cisplatin chemotherapy cycles.

In this study, the incidence of CIA in the elderly was 9.46%, which was higher than that in younger patients. This is consistent with previous experimental and clinical studies.Citation16,Citation17 The older patient is susceptible to nephrotoxicity, due to specific anatomical and functional changes, including kidney vasculature, filtration, and tubulointerstitial function.Citation18 However, we did not find that age and renal function were independent risk factors for CIA in the elderly. Previous studies had similar results.Citation19 Recently, Lavolé et al also found no association between age and cisplatin nephrotoxicity, and most patients experienced grade 1 CIA.Citation20 Therefore, cancer patients requiring cisplatin treatment should not be refused based on age or moderate, age-related renal dysfunction.

ACEI/ARB usage was an independent risk factor for CIA in the elderly. ACEI/ARBs are commonly used for several chronic conditions, such as hypertension, CKD, diabetic nephropathy, and congestive heart failure. With the increasing prevalence of these chronic conditions in the older population, ACEI/ARBs are more commonly used for the elderly.Citation1 Almanric et al showed that ACEI/ARBs were used in 29/80 patients (36%), and taking an ACEI or an ARB resulted in an increase of 12.1 µmol/L (95% CI: –15.0, 39.2) in the SCr level, but this increase was found to be statistically insignificant in a multivariate linear and logistic regression analyses.Citation21 This result was different from our study. This difference may be explained by the possibility that the CIA criteria were different in each study, or that the research population only with stage 4 nonsmall-cell lung cancer or with different tumor types was different. ACEI/ARBs can cause the vasodilation of both afferent and efferent arterioles, but the effect is more significant in the latter,Citation22 which can interfere with the renal autoregulation of the GFR; the resulting aggravated renal ischemia constitutes a higher risk for AKI. Moreover, studies have shown that plasma renin activity and plasma aldosterone concentration are elevated after cisplatin administration, which also results in GFR decline.Citation23 ACEI/ARBs may suppress the activity of the renin-angiotensin system that maintains the GFR, aggravating kidney ischemia and delaying cisplatin excretion.Citation24 Recently, a clinical study also found that ACEI use was associated with renal toxicity during platinum-based chemoradiation.Citation25 Therefore, the discontinuation of ACEI/ARBs use should be suggested when patients undergo chemotherapy with cisplatin.

CIA in the elderly was positively associated with a single cisplatin dose administered in 1 day. Several studies have shown that cisplatin treatment divided into smaller doses and administered over several days was effective and well tolerated.Citation26,Citation27 Espeli et al found that weekly cisplatin chemotherapy had less adverse effects than a 3-weekly regimen.Citation28 Lavolé et al investigated the rapid outpatient administration of a single dose of cisplatin at ≥75 mg/m2 and found that it was feasible, without a high risk of nephrotoxicity,Citation20 which is in accordance with our study. However, they found that cisplatin at a dose ≥100 mg/m2 during the first cycle (HR = 9.5, CI = 3.2–28) was an independent risk factor predictive of nephrotoxicity. However, in our study, the dose of cisplatin was not associated with CIA. This was possibly related to the smaller dose, but a further prospective study is required to verify this hypothesis. Recently, a meta-analysis revealed that a weekly low-dose regimen had increased compliance and significantly less toxicity than a 3-weekly high-dose regimen.Citation29 It is known that an increased incidence of cisplatin-induced acute nephrotoxicity is related to high-peak plasma-free platinum concentrations (Cmax).Citation30 The nephrotoxic effect of cisplatin, which accumulates in the kidneys, is proportional to the amount of the drug that is accumulated.Citation31 Two to 5 days of successive cisplatin administration, as opposed to the 1-day administration of a given total dose, can reduce cisplatin nephrotoxicity.Citation32 Therefore, older patients should avoid 1-day, single administration of cisplatin to reduce CIA.

The present study had a few limitations. First, because of the retrospective nature of this study in a single institution and a potential patient selection bias, a multi-center, large-scaled, prospective study is needed to confirm these results and to ensure the generalizability of our data. Second, patients with different tumor types may be heterogeneous due to different tumor staging and severity grades. Third, we need to further assess the role of hydration, including oral hydration, because we only considered intravenous hydration due to our inability to obtain questionnaires regarding the volume of oral hydration.

Conclusion

The incidence of CIA in the elderly was higher than that in contemporary younger patients. We identified the single administration of cisplatin and ACEI/ARBs use as independent risk factors for developing CIA in the elderly.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the 973 program (2013CB530800), the Twelfth Five-Year National Key Technology Research and Development Program (2015BAI12B06, 2013BAI09B05), the 863 program (2012AA02A512), and the National Nature Science Foundation of China (81670694, 81401160, 81070267). The authors gratefully acknowledge Professor Shun-chang Jiao, Yi Hu and Guang-hai Dai (Department of Oncology, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China) for providing data.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FuscoSGarastoSCorsonelloAMedication-induced nephrotoxicity in older patientsCurr Drug Metab2016617608625

- SmetanaKJrLacinaLSzaboPDvořánkováBAgeing as an important risk factor for cancerAnticancer Res201636105009501727798859

- SmithBDSmithGLHurriaAFuture of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nationJ Clin Oncol200927172758276519403886

- OhmichiMHayakawaJTasakaKKurachiHMurataYMechanisms of platinum drug resistanceTrends Pharmacol Sci200526311311615749154

- National Institutes of HealthClinical Trials Database Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.govAccessed May 21, 2018

- HaniganMHDevarajanPCisplatin nephrotoxicity: molecular mechanismsCancer Ther20031476118185852

- PablaNDongZCisplatin nephrotoxicity: mechanisms and renoprotective strategiesKidney Int2008739994100718272962

- ManoharSLeungNCisplatin nephrotoxicity: a review of the literatureJ Nephrol2018311152528382507

- KilbrideHSStevensPEEaglestoneGAccuracy of the MDRD (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease) study and CKD-EPI (CKD Epidemiology Collaboration) equations for estimation of GFR in the elderlyAm J Kidney Dis2013611576622889713

- MichelsWMGrootendorstDCVerduijnMPerformance of the Cockcroft-Gault, MDRD, and new CKD-EPI formulas in relation to GFR, age, and body sizeClin J Am Soc Nephrol2010561003100920299365

- LatchaSJaimesEAPatilSLong-term renal outcomes after cisplatin treatmentClin J Am Soc Nephrol20161171173117927073199

- MizunoTSatoWIshikawaKKDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) criteria could be a useful outcome predictor of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injuryOncology201282635435922722365

- MáthéCBohácsADuffekLCisplatin nephrotoxicity aggravated by cardiovascular disease and diabetes in lung cancer patientsEur Respir J201137488889420650984

- NinomiyaKHottaKHisamoto-SatoAShort-term low-volume hydration in cisplatin-based chemotherapy for patients with lung cancer: the second prospective feasibility study in the Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group Trial 1201Int J Clin Oncol2016211818726093520

- CronaDJFasoANishijimaTFA systematic review of strategies to prevent cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicityOncologist201722560961928438887

- EspandiariPRosenzweigBZhangJAge-related differences in susceptibility to cisplatin-induced renal toxicityJ Appl Toxicol201030217218219839026

- WenJZengMShuYAging increases the susceptibility of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicityAge (Dordr)201537611226534724

- RosnerMHAcute kidney injury in the elderlyClin Geriatr Med201329356557823849008

- HrusheskyWJShimpWKennedyBJLack of age-dependent cisplatin nephrotoxicityAm J Med19847645795846538750

- LavoléADanelSBaudrinLRoutine administration of a single dose of cisplatin ≥75 mg/m2 after short hydration in an outpatient lung-cancer clinicBull Cancer2012994E43E4822450449

- AlmanricKMarceauNCantinABertinÉRisk factors for nephrotoxicity associated with cisplatinCan J Hosp Pharm20177029910628487576

- PalmerBFRenal dysfunction complicating the treatment of hypertensionN Engl J Med2002347161256126112393824

- KurtEManavogluODilekKOrhanBEvrenselTEffect of cisplatin on plasma renin activity and serum aldosterone levelsClin Nephrol199952639739810604651

- KomakiKKusabaTTanakaMLower blood pressure and risk of cisplatin nephrotoxicity: a retrospective cohort studyBMC Cancer201717114428219368

- SpiottoMTCaoHMellLTobackFGACE inhibitors predict for acute kidney injury during chemoradiation for head and neck cancerAnticancer Drugs201526334334925486599

- RadesDSeidlDJanssenSChemoradiation of locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head-and-neck (LASCCHN): is 20 mg/m2 cisplatin on five days every four weeks an alternative to 100 mg/m2 cisplatin every three weeks?Oral Oncol201659677227424184

- UtkanGBüyükçelikAYalçinBDivided dose of cisplatin combined with gemcitabine in malignant mesotheliomaLung Cancer200653336737416828196

- EspeliVZuccaEGhielminiMWeekly and 3-weekly cisplatin concurrent with intensity-modulated radiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell cancerOral Oncol201248326627122079100

- SzturzPWoutersKKiyotaNWeekly low-dose versus three-weekly high-dose cisplatin for concurrent chemoradiation in locoregionally advanced non-nasopharyngeal head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of aggregate dataOncologist20172291056106628533474

- ReecePAStaffordIRussellJKhanMGillPGCreatinine clearance as a predictor of ultrafilterable platinum disposition in cancer patients treated with cisplatin: relationship between peak ultrafilterable platinum plasma levels and nephrotoxicityJ Clin Oncol1987523043093806171

- AranyISafirsteinRLCisplatin nephrotoxicitySemin Nephrol200323546046413680535

- CavalettiGTrediciGPizziniGMinoiaATissue platinum concentrations and cisplatin schedulesLancet1990336872110031004