Abstract

Background

The aim of the study was to conduct subgroup analyses of therapeutic effects of 12-month denosumab therapy on the percentage change in bone mineral density (BMD) from baseline in the lumber spine and femoral neck.

Materials and methods

We prospectively evaluated the BMD of the lumbar spine and femoral neck of 100 hormone receptor-positive, clinical stage I–IIIA postoperative postmenopausal breast cancer patients, for whom treatment with aromatase inhibitors (AIs) as adjuvant endocrine therapy was scheduled. The primary endpoint was the percent change in lumbar spine BMD from baseline to 12 months. Patient subgroups were analyzed according to baseline variables that are known risk factors for bone loss, including previous AI therapy, age, time since menopause, baseline body mass index (BMI), and baseline BMD T-score.

Results

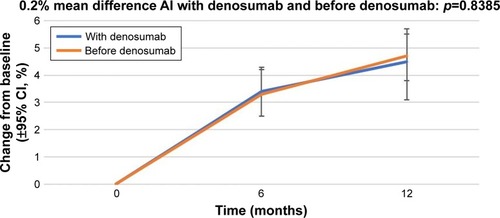

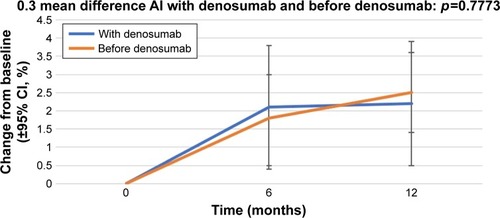

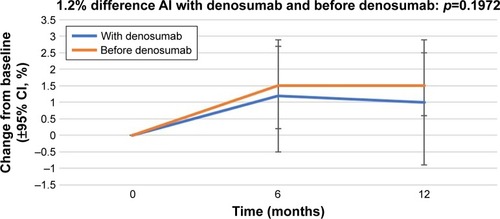

At 12 months, lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.7%; the patients who were administered AI therapy prior to denosumab (n=70) demonstrated a 4.7% increase in BMD, and the patients who received denosumab at the start of AI therapy (n=30) demonstrated a 4.5% increase in BMD (p=0.8385). Additionally, 2.4% and 1.4% increases in BMD of the right and left femoral neck, respectively, were observed. Initiation of AI (with denosumab, before denosumab), type of AI (non-steroidal, steroidal), age (<65, ≥65 years), time since menopause (≤5, >5 years), BMI (<25, ≥25 kg/m2), and T-score (≤−1.0, >−1.0) of the right femoral neck were as follows: (2.2%, 2.5%, p=0.7773), (2.6%, 0.9%, p=0.1726), (2.5%, 2.3%, p=0.7594), (2.1%, 2.4%, p=0.2034), (2.1%, 2.9%, p=0.2034), and (2.3%, 2.7%, p=0.6823), respectively. Initiation of AI (with denosumab, before denosumab), type of AI (non-steroidal, steroidal), age (<65, ≥65 years), time since menopause (≤5, >5 years), BMI (<25, ≥25 kg/m2), and T-score (≤−1.0, >−1.0) of the left femoral neck were as follows: (1.0%, 1.5%, p=0.1972), (1.2%, 2.7%, p=0.2931), (1.4%, 1.3%, p=0.8817), (−0.1%, 1.6%, p=0.1766), (1.3%, 1.9%, p=0.6465), and (1.5%, 1.1%, p=0.6573), respectively.

Conclusion

Twice-yearly treatment with denosumab was associated with increased BMD among Japanese women receiving adjuvant AI therapy, regardless of the baseline characteristics or skeletal site.

Keywords:

Introduction

Several large clinical trials have shown that, compared with tamoxifen, third-generation aromatase inhibitors (AIs) administered either alone or sequentially after 2–3 years of tamoxifen treatment for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer in postmenopausal women resulted in a longer disease-free survival and fewer endometrial and thromboembolic adverse events.Citation1–Citation6 Therefore, AIs are widely used by patients with postmenopausal breast cancer as a first-line adjuvant hormonal therapy. AIs inhibit the conversion of androgens to estrogens, resulting in a significant decline in estrogen levels, which in turn leads to lower bone mineral density (BMD). Moreover, several studies have reported that the BMD loss observed in postmenopausal breast cancer patients receiving long-term AIs is twice that observed in normal postmenopausal women of the same age.Citation4–Citation6 Therefore, patients receiving AIs are at increased risk for bone fracture, which can reduce their quality of life.Citation7,Citation8 Efforts to prevent BMD loss are thus needed.

We previously reported the results of a 12-month, non-randomized prospective study, which demonstrated that denosumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against receptor activator of nuclear-factor kappa-B ligand, increased BMD in the lumbar spine and femoral neck in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer who were receiving adjuvant AI therapy and demonstrated evidence of low bone mass.Citation9 Thus far in Japan, the efficacy of denosumab in the treatment of AI-associated bone loss has not been evaluated in a prospective study. Moreover, it is important to evaluate the outcomes of denosumab according to baseline and disease characteristics, to identify patients who might yield more benefits from receiving denosumab and those who would not. Patient subgroups were analyzed according to baseline variables that are known risk factors for bone loss, including previous AI therapy, age, time since menopause, baseline body mass index (BMI), and baseline BMD T-score. Herein, we present the results of these subgroup analyses of the therapeutic effects of 12-month denosumab therapy on the percentage change in BMD from baseline in the lumber spine and femoral neck.

Materials and methods

Patients

Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described previously. Briefly, data for postmenopausal women with early stage, histologically confirmed, hormone receptor-positive invasive breast cancer who were scheduled to receive AIs as adjuvant endocrine therapy or were in the process of receiving AI adjuvant therapy were included for analysis. The inclusion criteria also included completion of the chemotherapy regimen ≥4 weeks before study entry and evidence of low bone mass (lumbar spine, right femoral neck, and left femoral neck BMD corresponding to a T-score classification of −1.0 to −2.5). Key exclusion criteria included osteoporosis (T-score <−2.5), prior vertebral diseases, and current active dental problems including infection of the teeth or jawbone.

Study design

This non-randomized prospective study was conducted at 3 institutions in Japan. Patients were scheduled to receive 60 mg denosumab subcutaneously every 6 months. All patients were prescribed calcium (1 g/day) and vitamin D (≥400 IU/day). No change in AI therapy was mandated upon study participation. Approvals from appropriate research ethics committees were obtained for each participating study center. All patients provided written informed consent before participating. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine on August 2, 2013, and conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. This study was registered with the UMIN Clinical Trial Registry (UMIN-CTR, UMIN000027425). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Subgroup analyses

Analyses of the percentage change in BMD from baseline in the lumbar spine and femoral neck at 12 months were conducted in the following subgroups of patients: start of AI therapy (with denosumab, before denosumab), type of AI therapy (steroidal, non-steroidal), age (<65, ≥65 years), time since menopause (≤5, >5 years), baseline BMI (<20, ≥20 kg/m2), and BMD (−2.5< T-score <−1.0, T-score ≥−1.0). Subgroup analyses for the primary endpoint involved a post hoc analysis.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 74 patients was calculated to achieve a statistical power of 80% and to detect a 4% difference in the percent change in lumbar spine (L1–L4) BMD from baseline to 12 months. To allow for a 20% dropout rate, at least 90 patients were required. Paired t-tests were used to compare the two groups. p-values reported were based on a two-sided comparison. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP software version 12.

Results

A complete description of the baseline disease characteristics and disposition has been reported. The mean age (range) was 64 (54–89) years. A total of 103 patients were enrolled and received denosumab thrice, at 0, 6, and 12 months. All patients were included in the subgroup analyses. We found that 30% of patients received denosumab at the start of AI therapy and 89% of patients received non-steroidal AI therapy (anastrozole or letrozole); the other patients received steroidal AI therapy (exemestane). Moreover, 51.0% of patients were aged <65 years and 87.0% patients had been postmenopausal for longer than 5 years ().

Table 1 Summary of baseline variables

BMD

The percentage change in the lumbar spine BMD from baseline (±95% CI) over 12 months in the patients who received AIs with denosumab and those who received AIs before denosumab is shown in . At 12 months, the patients who were administered AI therapy prior to denosumab (n=70) demonstrated a 4.7% increase in BMD, and the patients who received denosumab at the start of AI therapy (n=30) demonstrated a 4.5% increase in BMD.

Figure 1 Percentage change in bone mineral density in the lumbar spine from baseline (±95% CI) over 12 months in patients who started receiving AIs with denosumab (“With denosumab”) and those who had received AI before the initiation of denosumab therapy (“Before denosumab”).

The percentage change in BMD in the right femoral neck from baseline (±95% CI) over 12 months in the patients who received AIs with denosumab and those who received AIs before denosumab is shown in . At 12 months, the patients who were administered AI therapy prior to denosumab demonstrated a 2.2% increase in BMD, and the patients who received denosumab at the start of AI therapy demonstrated a 2.5% increase in BMD. The percentage change in BMD in the left femoral neck from baseline (±95% CI) over 12 months in the patients who received AIs with denosumab and those who received AIs before denosumab is shown in . At 12 months, the patients who were administered AI therapy prior to denosumab demonstrated a 1.5% increase in BMD, and the patients who received denosumab at the start of AI therapy demonstrated a 1.0% increase in BMD. The BMD of patients administered AIs before denosumab showed a greater increase, but without statistical significance.

Figure 2 Percentage change in bone mineral density in the right femoral neck from baseline (±95% CI) over 12 months in patients who started receiving AIs with denosumab (“With denosumab”) and those who had received AI before the initiation of denosumab therapy (“Before denosumab”).

Figure 3 Percentage change in BMD in the left femoral neck from baseline (±95% CI) over 12 months in patients who started receiving AIs with denosumab (“With denosumab”) and those who had received AI before the initiation of denosumab therapy (“Before denosumab”).

Subgroup analyses of the treatment effects of denosumab at 12 months (least squares mean percentage difference [95% CI]) are shown in .

Table 2 Subgroup analyses of the therapeutic effects of denosumab at 12 months

Fractures

At month 12, no non-traumatic clinical fractures occurred in patients receiving AI therapy and denosumab.

Discussion

The increased risk for bone loss and fracture in breast cancer patients has become more evident following the use of AIs as adjuvant therapy. AI-induced bone loss occurs at more than twice the rate of physiologic postmenopausal bone loss.Citation10 AI-associated bone loss continues throughout the duration of therapy, at an average rate of 2% per year.Citation10,Citation11 It is estimated that >30% of patients treated with an AI will be diagnosed with osteoporosis in the subsequent years.Citation12 The negative effect of estrogen depletion on bone appears to be associated with both steroidal and non-steroidal AIs,Citation13,Citation14 although the former could induce less bone loss. The prevention of AI-induced bone loss has been the subject of discussions at the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the National Osteoporosis Foundation, and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, all of which have published guidelines and recommendations.Citation15–Citation18

A Japanese study revealed that the survival rate after hip fracture decreased dramatically over 2 years and the mortality risk remained high for 10 years.Citation19 This mortality risk was approximately double that of the general population, even at 10 years after hip fracture.

Therefore, a therapeutic approach that could prevent AI-induced bone loss and increase the BMD of the femoral necks is needed. The primary analysis of this study showed that denosumab was an effective agent for the management of such bone loss. Next, it was important to determine whether the overall benefit of denosumab treatment was influenced by baseline variables that are known risk factors for bone loss. The most notable fracture risk factors include advancing age (>65 years), AI therapy, chemotherapy-induced menopause, low BMI (<20 kg/m2), a family history of hip fracture, a personal history of fragility fracture, corticosteroid use, excessive alcohol consumption, and smoking.Citation20,Citation21

AI is associated with accelerated bone loss; therefore, if AI therapy has already been administered, there exists the possibility of reducing the effects of denosumab. In other words, the effect of denosumab becomes weak if the treatment period for AI is prolonged. In our trial, we showed that BMD at all skeletal sites similarly increased regardless of prior AI therapy. Age alone is among the strongest predictors of fracture. Because age significantly increases the risk for osteoporosis and fracture,Citation22 it is imperative to understand the contribution of denosumab to that risk in women aged ≥65 years. In our trial, we found that the BMD at all skeletal sites was similarly increased among patients aged <65 years and those aged ≥65 years. In general, low BMI in both men and women correlates with an increased age-adjusted risk for any type of fracture, whereas high BMI values decrease the risk for fracture.Citation23 In our trial, we revealed that BMD at all skeletal sites similarly increased among BMI <25 kg/m2 and BMI ≥25 kg/m2 groups.

Anastrozole and letrozole are non-steroidal inhibitors, whereas exemestane is a steroidal inhibitor of the aromatase enzyme, which converts androgens into estrogens. The decrease in BMD has been shown to be lower in patients treated with exemestane, possibly owing to its steroidal structure.Citation24 However, we observed the opposite for the lumber spine and right femoral neck, possibly owing to the small number of patients. In general, the lower the baseline BMD, the lower it will remain after 5 years of hormone therapy.Citation25 Our trial revealed the BMD at all skeletal sites was similarly increased among those with a T-score ≤−1.0 and those with a T-score >−1.0. There has been no evidence regarding the influence of denosumab in patients with a T-score ≤−2.5 or >−1.0 receiving AI treatment. Therefore, further studies examining patients with osteoporosis or normal BMD in consideration of these factors are warranted. We are in the process of conducting a single-arm prospective study (UMIN-CTR, UMIN000027425) of patients with a T-score classification of <−2.5 and a multicenter, randomized, comparative study regarding the efficacy of denosumab in postmenopausal patients with normal BMD and those with a T-score classification of >−1.0 receiving adjuvant AI (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03324932 and UMIN 000022256).

Conclusion

Currently, rebound-associated vertebral fracture after discontinuation of denosumab is a critical issue. Therefore, denosumab should not be discontinued as long as AIs are administered, even if patients are osteopenic. In summary, twice-yearly treatment with denosumab was associated with consistently greater gains in BMD among Japanese women receiving adjuvant AI therapy, regardless of the baseline characteristics or skeletal site.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KaufmannMJonatWHilfrichJImproved overall survival in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer after anastrozole initiated after treatment with tamoxifen compared with continued tamoxifen: the ARNO 95 StudyJ Clin Oncol200725192664267017563395

- LandSRWickerhamDLCostantinoJPPatient-reported symptoms and quality of life during treatment with tamoxifen or raloxifene for breast cancer prevention: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trialJAMA2006295232742275116754728

- Breast International Group (BIG) 1-98 Collaborative GroupThürlimannBKeshaviahAA comparison of letrozole and tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with early breast cancerN Engl J Med2005353262747275716382061

- HowellACuzickJBaumMATAC Trialists’ GroupResults of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years’ adjuvant treatment for breast cancerLancet20053659453606215639680

- Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination Trialists’ GroupBuzdarAHowellAComprehensive side-effect profile of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: long-term safety analysis of the ATAC trialLancet Oncol20067863364316887480

- CoombesRCHallEGibsonLJIntergroup Exemestane StudyA randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancerN Engl J Med2004350111081109215014181

- EastellRHannonRLong-term effects of aromatase inhibitors on boneJ Steroid Biochem Mol Biol2005951–515115615970439

- LonningPEGeislerJKragLEEffects of exemestane administered for 2 years versus placebo on bone mineral density, bone biomark-ers, and plasma lipids in patients with surgically resected early breast cancerJ Clin Oncol200523225126513715983390

- NakatsukasaKKoyamaHOuchiYEffect of denosumab administration on low bone mineral density (T-score −1.0 to −2.5) in postmenopausal Japanese women receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors for non-metastatic breast cancerJ Bone Miner Metab Epub2017117

- HadjiPAromatase inhibitor-associated bone loss in breast cancer patients is distinct from postmenopausal osteoporosisCrit Rev Oncol Hematol2009691738218757208

- EastellRHannonRACuzickJATAC Trialists’ GroupEffect of an aromatase inhibitor on BMD and bone turnover markers: 2-year results of the Anastrozole, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) trial (18233230)J Bone Miner Res20062181215122316869719

- EastellRAdamsJEColemanREEffect of anastrozole on bone mineral density: 5-year results from the anastrozole, tamoxifen, alone or in combination trial 18233230J Clin Oncol20082671051105718309940

- HadjiPZillerMAlbertUSKalderMAssessment of fracture risk in women with breast cancer using current vs emerging guidelinesBr J Cancer2010102464565020087347

- ColemanREBanksLMGirgisSIIntergroup Exemestane Study GroupSkeletal effects of exemestane on bone-mineral density, bone biomarkers, and fracture incidence in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer participating in the Intergroup Exemestane Study (IES): a randomised controlled studyLancet Oncol20078211912717267326

- WinerEPHudisCBursteinHJAmerican Society of Clinical Oncology technology assessment on the use of aromatase inhibitors as adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: status report 2004J Clin Oncol200523361962915545664

- HilnerBEIngleJNChlebowskiRTAmerican Society of Clinical OncologyAmerican Society of Clinical Oncology 2003 update on the role of bisphosphonates and bone health issues in women with breast cancerJ Clin Oncol200321214042405712963702

- National Osteoporosis FoundationClinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis [cited 2017 Mar 4] Available from: https://my.nof.org/bone-source/education/clinicians-guide-to-the-prevention-and-treatment-of-osteoporosisAccessed March 4, 2017

- HodgsonSFWattsNBBilezikianJPAACE Osteoporosis Task ForceAmerican Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: 2001 edition, with selected updates for 2003Endocr Pract20039654456414715483

- TsuboiMHasegawaYSuzukiSWingstrandHThorngrenKGMortality and mobility after hip fracture in Japan: a ten-year follow-upJ Bone Joint Surg Br200789446146617463112

- WeilbaecherKNGuiseTAMcCauleyLKCancer to bone: a fatal attractionNat Rev Cancer201111641142521593787

- LesterJEDodwellDPurohitOPPrevention of anastrozole-induced bone loss with monthly oral ibandronate during adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancerClin Cancer Res200814196336634218829518

- BeckerTLipscombeLNarodSSimmonsCAndersonGMRochonPASystematic review of bone health in older women treated with aro-matase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancerJ Am Geriatr Soc20126091761176722985145

- PalermoATuccinardiDDefeudisGBMI and BMD: the potential interplay between obesity and bone fragilityInt J Environ Res Public Health2016136E54427240395

- TangSCWomen and bone health: maximizing the benefits of aromatase inhibitor therapyOncology2010791–2132621051913

- EastellRAdamsJEColemanREEffect of anastrozole on bone mineral density: 5-year results from the anastrozole, tamoxifen, alone or in combination trial 18233230J Clin Oncol20082671051105818309940