Abstract

Asthma is the most common chronic airway disease in children, with more than half the reported cases of persistent asthma starting in children below the age of 3 years. Asthma diagnosis in preschool children has proven to be challenging due to the heterogeneity of the disease, the continuing development of the immune system in such a young population, and lack of diagnostic options such as lung function measurement. Early diagnosis and treatment of asthmatic symptoms will improve patients’ quality of life and help reduce disease morbidity. However, validated treatment options are scarce due to paucity of data and lack of conclusive studies in such a young patient population. Adjusting study design and endpoints to capture more reliable data with minimal risk of harm to patients is necessary. This thematic series review outlines the current position on preschool asthma, consolidates the current understanding of risk factors and diagnostic hurdles, and emphasizes the importance of early detection and management to help improve patients’ quality of life, both present and future. Particular focus was given to anticholinergics and their emerging role in the treatment and control of asthma in pediatric patients.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Asthma burden of disease

More than 300 million people worldwide are estimated to be affected by asthma.Citation1–Citation3 The World Health Organization predicts that this number will increase by more than 100 million by 2025.Citation2 Asthma is one of the most frequent chronic diseases observed in children and adolescents, and the most prevalent airway disease in this age group.Citation4 Globally, approximately 14% of children experience asthma symptoms such as wheezing, shortness of breath and chest tightness.Citation4,Citation5 In the USA, an estimated 7 million children and adolescents suffer from asthma,Citation6 and in the UK, approximately 10% of children receive treatment for asthma symptoms.Citation7 The majority of recorded persistent asthma cases begin before the age of 3 years, and up to 80% before the age of 6 years. Early symptoms are associated with increased disease severity and bronchial hyperresponsiveness.Citation8 Although most patients begin to display symptoms before the age of 5 or 6, the diagnosis of asthma in infants and preschoolers is more challenging than in older children and adults.Citation9

Defining asthma

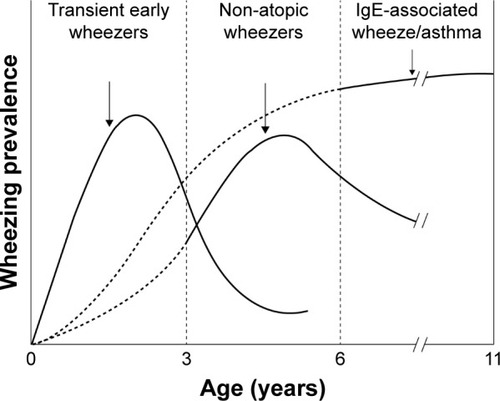

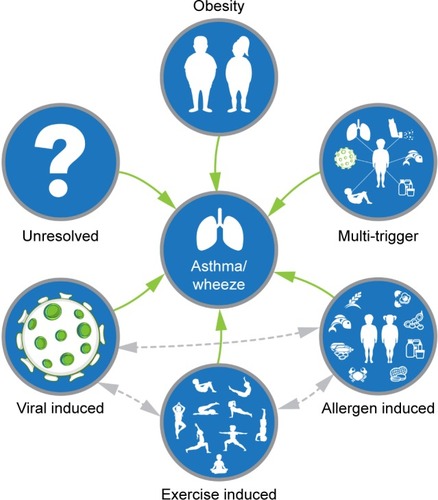

The International Consensus Report on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asthma defines asthma as a chronic inflammatory disease displaying symptoms associated with variable airflow obstruction that is often reversible, either spontaneously or with treatment.Citation10 Wheezing has emerged as the most important symptom for the identification of asthma.Citation11 The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) report defines asthma as having a variable clinical spectrum, with wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness and cough.Citation4 The definitions of asthma in children <6 years are often poorly described and confusing, making the diagnosis of the disease in preschool children difficult. The European Respiratory Society task force proposed the use of terms “episodic (viral) wheeze” (for children with intermittent wheeze and who are fine between episodes) and “multiple-trigger wheeze” (for children who wheeze both during and after discrete episodes).Citation9 Other definitions have also been used to clarify the different phenotypes of preschool wheezing disorders; for example, the presence of transient early wheezing in children <3 years, non-atopic wheezing in children aged 3–6 years, and IgE-mediated wheeze in older children ().Citation8 However, these definitions of preschool asthma-like symptoms may be considered too simplistic. More recent studies suggest these definitions reflect disease severity and that they are likely to vary with time.Citation12 A specific cause for the development of asthma has not been identified; however, interactions between the environment and genetic factors of each individual play a role.Citation13 These factors include viral infections, atopy, prematurity, exposure to tobacco smoke, exposure to elevated levels of air pollution, eczema or family history of asthma, or blood eosinophilia ().Citation8,Citation14,Citation15

Figure 1 Proposed yearly peak prevalence of wheezing phenotypes in children.

Figure 2 Pediatric asthma is a heterogeneous condition with multiple phenotypes arising from different underlying pathophysiologies.

By the time they reach school age, approximately half of preschool children diagnosed with wheeze become asymptomatic irrespective of treatment. However, in atopic and more severe cases, asthma symptoms have a higher probability of persisting for life.Citation16 While remission from childhood asthma is not uncommon, it becomes less likely with increasing severity of early symptoms. Currently, there is no primary prevention tactic; nevertheless, suggestions include avoiding exposure to tobacco smoke,Citation17 avoiding cesarean sectionsCitation18 and encouraging breastfeedingCitation18,Citation19 to decrease the risk of future development of asthma. There is evidence indicating breastfeeding is protective against childhood asthma and wheezing disorders.Citation19 The impact of breastfeeding on respiratory health may vary across countries as culture and socioeconomic changes occur.Citation18,Citation19

This thematic series review discusses the challenges associated with diagnosing asthma in preschool children and identifies areas of research that are intended to improve the diagnostic process. We also make suggestions for timely and appropriate management of preschool asthma to improve the patient’s quality of life, focusing on anticholinergics and their role in controlling the disease.

Challenges in diagnosis

The development of asthma-like symptoms and wheezing in preschool children can have a major impact on the quality of life of patients and their families, as well as public health if not correctly managed.Citation16 The first, and most important, step is to clearly identify which children are at risk of persistent asthma to allow the implementation of early management strategies, resulting in reduced morbidity and mortality. Guidelines to date still do not clearly differentiate between the definition of asthma in adult and pediatric patients due to the complexity and diversity of the disease. Only after the 2014 revision of the GINA report was the concept that asthma manifests in children under 5 years of age acknowledged.Citation4

The maturing of the respiratory and immune systems, the natural history of the disease, difficulty in diagnosis due to lack of reliable and reproducible tests, difficulty in delivering treatment and the unpredictable response to treatment are the most frequently cited causes of difficulties faced when diagnosing children.Citation16

Asthma is the primary diagnosis for one-third of pediatric emergency department (ED) visits,Citation20 and is a frequent reason for preventable hospitalizationCitation21,Citation22 and absenteeism from school.Citation23,Citation24 Nevertheless, it is estimated that asthma is still under-diagnosed in up to 75% of patients who present asthma-like symptoms, and approximately 11% of patients in primary care are erroneously prescribed inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).Citation20 This emphasizes the need for a standardized definition for the diagnosis of asthma in pediatric patients. Using a common systematic approach for asthma management can significantly improve outcomes. However, the dissemination and implementation of these recommendations are still a major challenge.Citation25

Making a definite asthma diagnosis in children <5 years is difficult and can have important clinical consequences. Although FEV1 is the preferred outcome variable of the U.S. Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) for asthma control in adults,Citation26 it is not the best measure for children with asthma. These patients often present normal lung function, and therefore normal FEV1 values in the absence of symptoms; however, during acute exacerbations they develop severe airflow obstruction.Citation27 A study examining the relationship between FEV1 and other clinical parameters used to diagnose asthma found that parent-reported symptoms, health care utilization, and functional health status measures are more helpful in characterizing asthma status than FEV1.Citation27,Citation28

Treatment recommendations

The GINA report recommends a probability-based approach, using frequency and severity of symptoms to guide treatment decisions, with a therapeutic trial of a controller medication.Citation4,Citation29 A large percentage of preschool children who present asthma-like symptoms are often treated with ICS to control inflammation. It was also suggested that early treatment with ICS could reduce the risk of developing irreversible airway obstruction. However, there are multiple studies emerging, with contradictory results as to the effect of ICS in such young patients. Two studies with ICS in wheezy infants and preschool children did not see any improvement.Citation30,Citation31 This suboptimal response to medication is most likely due, in part, to variability of the natural history of the disease.

A serious challenge for the diagnosis of asthma is the underestimation of the severity of the disease by parents, guardians and patients.Citation32 It can be difficult to assess symptoms and the extent to which a child has adapted its lifestyle to avoid symptoms. This adaptation could mask distress or discomfort from parents/guardians, as many parents believe that if the child is not suffering from obvious symptoms, such as audible wheeze, there is no real problem.Citation33 Clear and open patient–physician communication to address patient-specific concerns can help the treating physician identify symptoms and make a more informed diagnosis, allowing the correct and appropriate treatment prescriptions and adaptations to be made.Citation34

Sensitization and allergen-induced asthma

Sensitization to common atopic aeroallergens has been found to play a significant role in the development of asthma and should be assessed during diagnosis. An Australian study found a correlation between early allergic sensitization and the development of persistent asthma.Citation35 Other data suggest that approximately two-thirds of the German asthma patient population is sensitized to at least one allergen.Citation36 Among children, approximately 40% have been found to be sensitized to inhalant allergens by early school age, and more than a quarter of these will eventually develop asthma.Citation36 It is believed that increased exposure to other children, pets or farm animals in early life may protect children from future development of asthma. Other studies have demonstrated that children with older siblings, or those who attended day care within the first 6 months of life, were less likely to develop asthma.Citation8 However, sensitization to certain allergens, such as fungi or cockroaches, can increase the risk of development of asthma in children.Citation37

Prediction models for the development of asthma in children may be used as tools to prevent delays in asthma diagnosis. Information provided by a predictive model can have a significant impact on the patient’s present and future quality of life. To date, approximately 23 predictive models of asthma have been developed for children. However, none of the models developed for preschool children have high positive predictive value or high sensitivity. This lack of accuracy makes them unsuitable for routine clinical use.Citation20

The accurate diagnosis of asthma in preschool children is a crucial step toward achieving control of the disease and optimizing the patient’s quality of life.

Impact of early symptoms on future health

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways characterized by complete or partial airway obstruction reversibility.Citation4 This chronic inflammation can result in airway remodeling that can have a negative effect on exacerbations, lung function and response to treatment.Citation38 Childhood-onset asthma has been associated with reduced lung function and narrower airways later in life, increasing the severity of symptoms and the risk of exacerbations at later ages.Citation39 In adults, ED visits and hospitalizations caused by exacerbations have also been associated with an increased risk of repeated exacerbations, asthma severity and asthma control, which is also applicable to children.Citation38

Asthma not only affects patients physically, but can have serious psychological repercussions if left uncontrolled or unrecognized. Data for mental health issues in children and adolescents with asthmatic symptoms are controversial. However, there are studies that suggest patients with asthma are more likely to suffer from a wide range of mental health problems compared with healthy counterparts, such as increased symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders. Negative situations and emotional distress can be associated with difficulty in breathing in many patients.Citation40 If young children are exposed to chronic levels of stress, they may develop coping mechanisms, such as behavioral and social adaptation. Patients who are able to adapt to the disease at an early age have been shown to experience less psychological morbidity and achieve better long-term management of the disease.Citation33

Identifiable risk factors to aid early detection

The importance of identifying asthma and wheezing, and employing management strategies in preschool children start to become evident when children reach school age. Identifying risk factors for asthma could be a key factor in disease management. For example, rapid early weight gain in young children has been associated with symptomatic growth dysregulation, which precedes impaired airway development and clinical wheezing.Citation41 An association between high body mass index (BMI) and wheezing and asthma in children has been observed. Studies have shown that children with higher BMI are more likely to suffer from a more severe form of the disease compared with children with lower BMI values.Citation42 If the disease is not controlled early on, this can negatively affect many aspects of a child’s development, including the learning process. Children with asthma have been found to have a higher school absence rate than their healthy peers.Citation43,Citation44 This can have a significant impact on their future education and has been suggested to be a predictor of school dropout.Citation44,Citation45

What are the available reliable treatment options for preschool children?

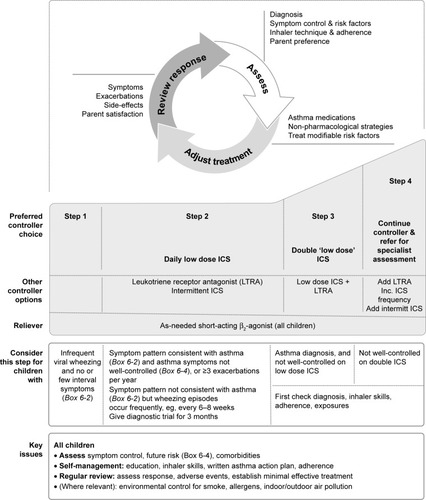

Treatment of preschool children with cough and wheeze depends on the severity of the symptoms. For children with infrequent wheezing, guidelines recommend the use of short-acting beta2-agonists as needed ().Citation4 For children with more persistent symptoms, ICS are the mainstay prescribed therapy.Citation4 ICS are the most effective anti-inflammatory therapy available for patients with asthma and their regular use has been found to improve asthma control and quality of life, and decrease risk of exacerbations.Citation46,Citation47 There is evidence to support the use of ICS in preschool children with asthma,Citation48,Citation49 and GINA recommends a daily low dose of ICS for preschool children if the symptom pattern becomes consistent with that of asthma ().Citation4 If symptoms worsen and are not well controlled, leukotriene receptor antagonists are suggested to be prescribed in conjunction with ICS, or the dose and frequency of ICS are to be increased (). It is important to be aware that the continuous use of ICS has been linked to growth retardation and may not have an effect in all children whose symptoms are not well controlled.Citation50 More recent studies have highlighted that individual ICS therapies have differing safety profiles that are noticeably better than those of oral steroids. The risk of side effects is considerably reduced when the lowest effective dose is prescribed. Furthermore, systemic availability is reduced through appropriate inhaler device selection and monitoring concomitant medication use.Citation51

Figure 3 GINA-recommended treatment steps for preschool children with asthma.

Abbreviations: GINA, The Global Initiative for Asthma; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid.

These contraindications may deter patients/parents from the correct use of medication.

Available treatment options for preschool children with asthma are limited, with more options available for children over the age of 6 years.

There is evidence to support the use of long-acting muscarinic antagonists in older children, and tiotropium Respimat® has been approved as an add-on to ICS/long-acting β2-agonists in patients with asthma in several countries. In the USA, it is approved for long-term, once-daily maintenance treatment of asthma in patients aged 6 years and older.Citation52 In the European Union, the indication for tiotropium Respimat has recently been updated for use as an add-on maintenance bronchodilator in patients aged 6 years and older with severe asthma who experienced one or more severe asthma exacerbation in the past year.Citation53 Recent clinical trials, spanning different age groups (6–11 years and 12–17 years), found improvements in lung function with tiotropium, and a safety and tolerability profile comparable with placebo.Citation54–Citation61 There are very few trials investigating the efficacy of potential treatments in children under 6 years of age due to the previously discussed discrepancies in diagnosis criteria. However, a recent small study in preschool children with persistent asthmatic symptoms was the first to assess the safety and efficacy of tiotropium in children aged 1–5 years.Citation62 Tiotropium demonstrated a comparable safety and tolerability profile with placebo, in line with safety outcomes previously reported in patients over 6 years old.Citation54–Citation61 However, the efficacy endpoints for this study were exploratory, even though the endpoints were defined and were used for descriptive analyses only. While changes in daytime asthma symptom scores were not significant, the exploratory analysis recorded a smaller number of children reporting adverse events (AEs) related to asthma exacerbations and symptoms in children taking tiotropium compared with those taking placebo.Citation62 Further studies are needed to establish the efficacy of tiotropium in this very young patient population.

The importance of the correct device for therapy delivery

Ensuring that the patient is receiving the correct therapy is an important step in disease management. The selection of an appropriate device should be considered just as important as the therapy choice, as the correct handling of inhalers is essential to ensure patients receive the prescribed dose. Each device used for administration of aerosol therapy has different mechanisms of operation, performance characteristics and requirements for correct use. This means that patients and caregivers must be correctly instructed on the use of each different inhaler device they are prescribed; otherwise it will result in the incorrect use of the device and improper delivery of therapy to the lungs. Aerosol devices that are used by adults may not be appropriate for children because of the complex steps necessary for their correct use. Young children may also lack sufficient inspiratory strength to use a dry powder inhaler.Citation63 Breath-actuated inhalers are impractical for use in children as their erratic breathing patterns will make their use difficult for children under the age of 5 years. Inspiratory flows and lung volumes are largely size-dependent and increase with age and body mass; therefore, many children will not be capable of generating sufficient flow for correct inhaler device use until the ages of 5 or 6 years. Preschool children also lack the coordination between actuation and inhalation for the use of a metered-dose inhaler (MDI), whereas school-age children may have the hand-breath coordination but may lack the ability to determine when to use the device.Citation63 Other difficulties encountered with the use of inhalers in infants are that they breathe predominantly through their noses up to the age of 6 months, and toddlers are generally not able to use a mouth piece.Citation63 Consequently, aerosol administration in this very young patient population requires different mouth pieces such as an aerosol mask for patients up to the age of 3 or 4 years, or valved holding chambers and spacers for slightly older patients able to use a mouth piece ().Citation63 A commonly used delivery system in children under the age of 5 years is nebulizers. The advantage of nebulizers is that they do not require patient cooperation. Nevertheless, less than 10% of aerosolized therapy reaches the lungs when using nebulizers, and a large proportion of the treatment is deposited on the face, a large proportion on the apparatus and the remainder lost to the surroundings.Citation64 Pressurized MDIs (pMDIs) allow a higher proportion of the therapy to reach the lung, but require coordination between inhaling and activating the inhaler. The use of a spacer eliminates the need for coordination between actuation and inhalation of a pMDI. The valved holding chamber/spacer has a one-way valve that allows aerosol to move out of the chamber at inhalation and keeps particles in the chamber upon exhalation. Neonates and infants should not use these spacers without a face mask to aid therapy deliveryCitation65 as they are unable to generate the inspiratory force required to open the one-way valve. The limitation encountered with face masks is that the delivery of therapy to the lungs is noticeably decreased.Citation64,Citation66 Recently, a study used the Respimat and the AeroChamber Plus® Flow-Vu® anti-static valved holding chamber for the delivery of aerosol to preschool patients.Citation62

Table 1 Choosing an aerosol device and interface for patients of different ages

The challenges faced in the development and testing of new treatment options for this patient population

Most treatment options for asthma and respiratory diseases are not designed for use in preschool children. There is an unmet need for therapy options in this patient demography. A reason for this shortfall is that determining the effect of child growth and development on therapies, and vice versa, is a challenge in pediatric research.Citation67 It has long been recognized that different asthma symptom patterns in childhood may be associated with variations in the natural history of the disease. The changeability in disease phenotype and improbability of a homogeneous patient population make it problematic to classify young patients or recruit them for trials. The various developmental stages of children at different ages will often require separate sub-analyses for infants, school-age children and adolescents to assess safety and efficacy of a treatment. This subdivision will inevitably increase the number of participants required per study.Citation67 As there is a scarcity of study participants, it will therefore increase the time needed to recruit enough participants for a study and require more effort to retain them. Once identified, it is likely that not all children with a disorder or condition will meet the eligibility criteria for a study.Citation67

There are strict regulations that restrict the range of research that can be undertaken with children. Placebo-controlled trials for efficacy are more regulated when children participate, especially if the children receiving the placebo are exposed to more than the minimal amount of risk. Other ethical considerations include parents’ reluctance to enroll their children in clinical trials due to concerns of safety and well-being for their child.Citation67

Challenges faced with clinical outcome measures

Defining and measuring appropriate outcome variables for preschool populations is problematic as they are less able to perform lung function analyses.Citation68 Pediatric investigators and agencies, such as the FDA, often do not agree on what is considered an acceptable measure. Clinical endpoints must be appropriate for the target population. FEV1 results are valuable for the diagnosis of asthma in adults; however, it is not always possible to ensure a preschool-age patient’s cooperation, and therefore, reliable and reproducible results.Citation69 Young children are often not able to perform specific ventilation, reducing the role of lung function testing and other physiologic tests in the diagnosis of children under the age of 5 years.Citation37 The American Thoracic Society/ERS joint expert panel has acknowledged that the current repeatability criteria for adult spirometry are not appropriate for preschool children and there is a severe lack of objective measures for children.Citation70 With preschool children still developing, most will not have the chest wall strength to carry out spirometry at the required intensity to produce FEV1 results. Forced expiratory volume in 0.5 seconds would be more physiologically appropriate for young children (<6 years) as their forced expiration is shorter than that of adults.Citation70 Changes in chest and lung anatomy, as well as the physiologic changes that occur during growth and development, affect lung function test results in very young patients.Citation71 Cooperation-free tests are the preferred method for screening of pediatric patients; however, these are generally available only in specialized centers due to the use of complex equipment.Citation69 Impulse oscillometry is a method that requires less patient cooperation compared with spirometry and may be useful in identifying children with lower airway obstruction in patients without obvious wheeze.Citation72

Using questionnaires, such as the Childhood Asthma Control Test, which allows scoring by both children and parents, has shown that children tend to assess their asthma control significantly lower than parents do.Citation73 This can be because children are not able to fully complete questionnaires on their own, or often parents or guardians rely on observation, which can result in incomplete reporting. An alternative endpoint to use would be symptom-free days. This is a useful endpoint for pediatric asthma studies and easier to record than symptom scores.Citation74

Identifying surrogate endpoints

With no tested reliable method for early detection of asthma currently available in the preschool-age demography, there is an urgent need to investigate this further. However, long placebo-controlled trials are considered unethical in such a young population and alternative endpoints need to be identified. Pharmacologic markers such as biomarkers, including measurement of fractional exhaled nitric oxide,Citation75 may serve as a surrogate endpoint.Citation76 The occurrence of AEs related to exacerbations and symptoms has, more recently, been proposed as a useful alternative endpoint in pediatric trials.Citation74 The FDA recognizes the use of surrogate endpoints as extremely promising for improving the efficiency in clinical research.Citation77 Incorporating surrogate endpoints could significantly accelerate the development of new therapies for infants, children and adolescents.Citation77 Surrogate endpoints may be used for early detection of safety issues that could point to toxicity problems of a new therapy.Citation77 Clinical trials designed to evaluate efficacy of a new drug are often too short and too small to detect rare AEs or events that occur after prolonged therapy.Citation78 Surrogate endpoints also do not directly measure clinical impact, but reflect therapeutic treatment effect, therefore their use can be controversial.Citation74,Citation77 However, due to the unique requirements of pediatric research, careful and appropriate use of surrogate endpoints could allow more information to be gathered about therapeutic interventions during short clinical testing phases.Citation74

Conclusion

With asthmatic symptoms present in young patients, and approximately 50% of patients with symptoms at 3 years of age likely to be later diagnosed with asthma, early detection and management of this chronic disease are essential to improve the patients’ quality of life, not only in the present, but also in the future. There is a significant deficit in reliable asthma identification measures and effective treatment strategies in preschool children. Further studies are needed to define pathogenesis, progression and outcomes of asthma in preschool children, as well as to identify efficacious interventions in this population.

Data sources and selection criteria

We based this review on the Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines published in 2018. We also included key publications by the World Health Organization. We searched for cited references in PubMed using the search terms “asthma,” “cough,” “wheezing,” “breathlessness,” “diagnosis,” “management,” “barriers,” “primary care,” “preschool” and “childhood.” Our personal research article library was used to investigate and review relevant publications.

Acknowledgments

The author takes full responsibility for the scope, direction, content of, and editorial decisions relating to the manuscript, was involved at all stages of development, and has approved the submitted manuscript. Medical writing assistance, in the form of the preparation and revision of the draft manuscript, was supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim and provided by Martina Stagno d’Alcontres, PhD, of MediTech Media, under the author’s conceptual direction and based on feedback from the author. Boehringer Ingelheim was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for factual accuracy only. The author would like to thank Kjeld Hansen, a member of the Patient Ambassador Group for the European Lung Foundation, for his input to the video summary of this manuscript.

Disclosure

The author has participated as a lecturer and speaker in scientific meetings and courses under the sponsorship of ALK Abello, Allergopharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Engelhard Arzneimittel, HAL Allergy, Infectopharm, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Novartis and as a member of the advisory board for ALK Abello, Boehringer Ingelheim, Engelhard Arzneimittel, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Stallergenes and Novartis. He was an investigator on the pediatric tiotropium studies. The author reports no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MasoliMFabianDHoltSBeasleyRGlobal Initiative for Asthma (GINA) ProgramThe global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee reportAllergy200459546947815080825

- BousquetJKhaltaevNGlobal Surveillance, Prevention and Control of Chronic Respiratory Diseases: A Comprehensive ApproachGenevaWorld Health Organization2007

- NunesCPereiraAMMorais-AlmeidaMAsthma costs and social impactAsthma Res Pract20173128078100

- Global Initiative for AsthmaGINA report: global strategy for asthma management and prevention Available from: http://ginasthma.org/2018-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/Accessed March 8, 2018

- AalbersRParkHSPositioning of long-acting muscarinic antagonists in the management of asthmaAllergy Asthma Immunol Res20179538639328677351

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionNational Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/nhis/default.htmAccessed December 12, 2017

- Asthma UKAsthma facts and statistics Available from: https://www.asthma.org.uk/about/media/facts-and-statistics/Accessed December 2, 2018

- MartinezFDDevelopment of wheezing disorders and asthma in preschool childrenPediatrics20021092 Suppl36236711826251

- BrandPLBaraldiEBisgaardHDefinition, assessment and treatment of wheezing disorders in preschool children: an evidence-based approachEur Respir J20083241096111018827155

- International consensus report on diagnosis and treatment of asthma. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, Maryland 20892. Publication no. 92-3091, March 1992Eur Respir J1992556016411612163

- AsherIPearceNGlobal burden of asthma among childrenInt J Tuberc Lung Dis201418111269127825299857

- SchultzADevadasonSGSavenijeOESlyPDLe SouëfPNBrandPLThe transient value of classifying preschool wheeze into episodic viral wheeze and multiple trigger wheezeActa Paediatr2010991566019764920

- van AalderenWMChildhood asthma: diagnosis and treatmentScientifica20122012118

- BeasleyRSempriniAMitchellEARisk factors for asthma: is prevention possible?Lancet201538699981075108526382999

- Kravitz-WirtzNTeixeiraSHajatAWooBCrowderKTakeuchiDEarly-life air pollution exposure, neighborhood poverty, and childhood asthma in the United States, 1990–2014Int J Environ Res Public Health2018156E111429848979

- PapadopoulosNGArakawaHCarlsenKHInternational consensus on (ICON) pediatric asthmaAllergy201267897699722702533

- LanneröEWickmanMPershagenGNordvallLMaternal smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of recurrent wheezing during the first years of life (BAMSE)Respir Res20067316396689

- ChuSChenQChenYBaoYWuMZhangJCesarean section without medical indication and risk of childhood asthma, and attenuation by breastfeedingPLoS One2017129e018492028922410

- DogaruCMNyffeneggerDPescatoreAMSpycherBDKuehniCEBreastfeeding and childhood asthma: systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Epidemiol2014179101153116724727807

- LuoGNkoyFLStoneBLSchmickDJohnsonMDA systematic review of predictive models for asthma development in childrenBMC Med Inform Decis Mak2015159926615519

- FloresGAbreuMTomany-KormanSMeurerJKeeping children with asthma out of hospitals: parents’ and physicians’ perspectives on how pediatric asthma hospitalizations can be preventedPediatrics2005116495796516199708

- NathJBHsiaRYChildren’s emergency department use for asthma, 2001–2010Acad Pediatr201515222523025596899

- WangLYZhongYWheelerLDirect and indirect costs of asthma in school-age childrenPrev Chronic Dis200521A11

- HsuJQinXBeaversSFMirabelliMCAsthma-related school absenteeism, morbidity, and modifiable factorsAm J Prev Med2016511233226873793

- KupczykMHaahtelaTCruzAAKunaPReduction of asthma burden is possible through National Asthma PlansAllergy201065441541920102359

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER)Guidance for industry – Orally inhaled and intranasal corticosteroids: evaluation of the effects on growth in children2007 Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm071968.pdfAccessed December 14, 2017

- SpahnJDCherniackRPaullKGelfandEWIs forced expiratory volume in one second the best measure of severity in childhood asthma?Am J Respir Crit Care Med2004169778478614754761

- SharekPJMayerMLLoewyLAgreement among measures of asthma status: a prospective study of low-income children with moderate to severe asthmaPediatrics2002110479780412359798

- ReddelHKBatemanEDBeckerAA summary of the new GINA strategy: a roadmap to asthma controlEur Respir J201546362263926206872

- SchokkerSKooiEMde VriesTWInhaled corticosteroids for recurrent respiratory symptoms in preschool children in general practice: randomized controlled trialPulm Pharmacol Ther2008211889717350868

- HofhuisWvan der WielECNieuwhofEMEfficacy of fluticasone propionate on lung function and symptoms in wheezy infantsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005171432833315531753

- SilvaCMBarrosLAsthma knowledge, subjective assessment of severity and symptom perception in parents of children with asthmaJ Asthma20135091002100923859138

- BartonCClarkeDSulaimanNAbramsonMCoping as a mediator of psychosocial impediments to optimal management and control of asthmaRespir Med200397774776112854624

- HaJFLongneckerNDoctor-patient communication: a reviewOchsner J2010101384321603354

- PeatJKSalomeCMWoolcockAJLongitudinal changes in atopy during a 4-year period: relation to bronchial hyperresponsiveness and respiratory symptoms in a population sample of Australian schoolchildrenJ Allergy Clin Immunol1990851 Pt 165742299108

- IlliSvon MutiusELauSThe pattern of atopic sensitization is associated with the development of asthma in childhoodJ Allergy Clin Immunol2001108570971411692093

- PedersenSEHurdSSLemanskeRFGlobal strategy for the diagnosis and management of asthma in children 5 years and youngerPediatr Pulmonol201146111720963782

- DoughertyRHFahyJVAcute exacerbations of asthma: epidemiology, biology and the exacerbation-prone phenotypeClin Exp Allergy200939219320219187331

- GradRMorganWJLong-term outcomes of early-onset wheeze and asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2012130229930722738675

- BaiardiniISicuroFBalbiFCanonicaGWBraidoFPsychological aspects in asthma: do psychological factors affect asthma management?Asthma Res Pract20151727965761

- LangJEObesity and asthma in children: current and future therapeutic optionsPaediatr Drugs201416317918824604125

- MaiXMNilssonLAxelsonOHigh body mass index, asthma and allergy in Swedish schoolchildren participating in the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood: Phase IIActa Paediatr200392101144114814632328

- MoonieSASterlingDAFiggsLCastroMAsthma status and severity affects missed school daysJ Sch Health2006761182416457681

- StridsmanCDahlbergEZandrénKHedmanLAsthma in adolescence affects daily life and school attendance – Two cross-sectional population-based studies 10 years apartNurs Open20174314314828694978

- MengYYBabeySHWolsteinJAsthma-related school absenteeism and school concentration of low-income students in CaliforniaPrev Chronic Dis20129E9822595322

- O’ByrnePMPharmacologic interventions to reduce the risk of asthma exacerbationsProc Am Thorac Soc20041210510816113421

- KupczykMDahlénBDahlénSEWhich anti-inflammatory drug should we use in asthma?Pol Arch Med Wewn20111211245545922210376

- Castro-RodriguezJAPedersenSThe role of inhaled corticosteroids in management of asthma in infants and preschoolersCurr Opin Pulm Med2013191545923143197

- BisgaardHAllenDBMilanowskiJKalevIWillitsLDaviesPTwelve-month safety and efficacy of inhaled fluticasone propionate in children aged 1 to 3 years with recurrent wheezingPediatrics20041132e87e9414754977

- GuilbertTWMorganWJZeigerRSLong-term inhaled corticosteroids in preschool children at high risk for asthmaN Engl J Med2006354191985199716687711

- WolfgramPMAllenDBEffects of inhaled corticosteroids on growth, bone metabolism, and adrenal functionAdv Pediatr201764133134528688596

- SPIRIVA® RESPIMAT® (tiotropium bromide) inhalation spray [prescribing information]Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.Ridgefield, CT Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/021936s007lbl.pdfAccessed December 14, 2017

- Boehringer IngelheimAsthma: expanded indication for SPIRIVA® Respimat® for people 6 years and older Available from: https://www.boehringer-ingelheim.com/press-release/expanded-asthma-indication-spiriva-respimat-euAccessed March 20, 2018

- VogelbergCMoroni-ZentgrafPLeonaviciute-KlimantavicieneMA randomised dose-ranging study of tiotropium Respimat® in children with symptomatic asthma despite inhaled corticosteroidsRespir Res2015162025851298

- VogelbergCEngelMMoroni-ZentgrafPTiotropium in asthmatic adolescents symptomatic despite inhaled corticosteroids: a randomised dose-ranging studyRespir Med201410891268127625081651

- HamelmannEBatemanEDVogelbergCTiotropium add-on therapy in adolescents with moderate asthma: a 1-year randomized controlled trialJ Allergy Clin Immunol2016138244145026960245

- KerstjensHAEngelMDahlRTiotropium in asthma poorly controlled with standard combination therapyN Engl J Med2012367131198120722938706

- KerstjensHACasaleTBBleeckerERTiotropium or salmeterol as add-on therapy to inhaled corticosteroids for patients with moderate symptomatic asthma: two replicate, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, active-comparator, randomised trialsLancet Respir Med20153536737625682232

- PaggiaroPHalpinDMBuhlRThe effect of tiotropium in symptomatic asthma despite low- to medium-dose inhaled corticosteroids: a randomized controlled trialJ Allergy Clin Immunol Pract20164110411326563670

- HamelmannEBernsteinJAVandewalkerMA randomised controlled trial of tiotropium in adolescents with severe symptomatic asthmaEur Respir J2017491160110027811070

- SzeflerSJMurphyKHarperT3rdA phase III randomized controlled trial of tiotropium add-on therapy in children with severe symptomatic asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol201714051277128728189771

- VrijlandtEJLEEl AzziGVandewalkerMSafety and efficacy of tiotropium in children aged 1–5 years with persistent asthmatic symptoms: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet Respir Med20186212713729361462

- AriAFinkJBGuidelines for aerosol devices in infants, children and adults: which to choose, why and how to achieve effective aerosol therapyExpert Rev Respir Med20115456157221859275

- SmithCGoldmanRDNebulizers versus pressurized metered-dose inhalers in preschool children with wheezingCan Fam Physician201258552853022734168

- DitchamWMurdzoskaJZhangGLung deposition of 99mTc-radiolabeled albuterol delivered through a pressurized metered dose inhaler and spacer with facemask or mouthpiece in children with asthmaJ Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv201427Suppl 1S63S7525054483

- AriAde AndradeADSheardMAlhamadBFinkJBPerformance comparisons of jet and mesh nebulizers using different interfaces in simulated spontaneously breathing adults and childrenJ Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv201528428128925493535

- FieldMJBermanREInstitute of Medicine (US) Committee on Clinical Research Involving ChildrenThe Ethical Conduct of Clinical Research Involving ChildrenWashington, DCNational Academy of Sciences2004

- British Thoracic Society, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines NetworkBritish guideline on the management of asthma – A national clinical guidelineSIGN2016153 Available from: https://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-153-british-guideline-on-the-management-of-asthma.htmlAccessed September 10, 2018

- SchlegelmilchRMKrammeRPulmonary function testingHandbook of Medical TechnologyBerlinSpringer201195119

- BeydonNDavisSDLombardiEAn official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: pulmonary function testing in preschool childrenAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007175121304134517545458

- ColeTJStanojevicSStocksJCoatesALHankinsonJLWadeAMAge- and size-related reference ranges: a case study of spirometry through childhood and adulthoodStat Med200928588089819065626

- KotwalNBerkovitsDVicencioAGUse of impulse oscillometry in evaluation of preschool children with chronic coughAm J Respir Crit Care Med2015191A3392

- DinakarCChippsBESECTION ON ALLERGY AND IMMUNOLOGY; SECTION ON PEDIATRIC PULMONOLOGY AND SLEEP MEDICINEClinical tools to assess asthma control in childrenPediatrics20171391e2016343828025241

- de BenedictisFMGuidiRCarraroSBaraldiETEDDY European Network of ExcellenceEndpoints in respiratory diseasesEur J Clin Pharmacol201167Suppl 1495921104409

- Sánchez-GarcíaSHabernau MenaAQuirceSBiomarkers in inflammometry pediatric asthma: utility in daily clinical practiceEur Clin Respir J201741135616028815006

- BernsBDémolisPScheulenMEHow can biomarkers become surrogate endpoints?Eur J Cancer suppl2007593740

- MolenberghsGOrmanCSurrogate endpoints: application in pediatric clinical trialsMulbergASilberSvan der AckerJNPediatric Drug Development, Concepts and ApplicationsHoboken, NJWiley Blackwell2009501511

- JonesTCCall for a new approach to the process of clinical trials and drug registrationBMJ2001322729192092311302912