Abstract

Prescriptions for opioid analgesics to manage moderate-to-severe chronic noncancer pain have increased markedly over the last decade, as have postmarketing reports of adverse events associated with opioids. As an unintentional consequence of greater prescription opioid utilization, there has been the parallel increase in misuse, abuse, and overdose, which are serious risks associated with all opioid analgesics. In response to these concerns, the Food and Drug Administration announced the requirement for a class-wide Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for long-acting and extended-release (ER) opioid analgesics in April 2011. An understanding of the details of this REMS will be of particular importance to primary care providers. The class-wide REMS is focused on educating health care providers and patients on appropriate prescribing and safe use of ER opioids. Support from primary care will be necessary for the success of this REMS, as these clinicians are the predominant providers of care and the main prescribers of opioid analgesics for patients with chronic pain. Although currently voluntary, future policy will likely dictate that providers undergo mandatory training to continue prescribing medications within this class. This article outlines the elements of the class-wide REMS for ER opioids and clarifies the impact on primary care providers with regard to training, patient education, and clinical practice.

Introduction

Prescription opioid analgesics have gained acceptance as effective treatments for moderate-to-severe chronic noncancer pain in properly selected patients.Citation1,Citation2 In 2009, approximately 23 million prescriptions of the extended-release (ER) opioid class were dispensed to more than 3.8 million unique patients.Citation3 However, an unintentional consequence of greater prescription opioid utilization has been the parallel increase in misuse, abuse, and overdose, which are serious risks associated with all opioid analgesics.Citation4–Citation6

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recognized the substantial risks associated with improper use of ER opioid formulations, given the large amount of active ingredient contained within a dose and the prolonged time to elimination.Citation7–Citation11 Under the authority of the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007, and as a result of stakeholder, industry, public, and advisory committee meetings held over several years, in April 2011 the FDA announced a class-wide Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for ER opioid analgesics.Citation12 A REMS is a required risk management plan that utilizes tools beyond routine labeling to ensure that the benefits of a medication outweigh the risks.Citation13 The intent of the class-wide REMS is to ensure that the therapeutic benefits of ER opioid formulations continue to outweigh the risks, particularly addiction, unintentional overdose, and death resulting from inappropriate prescribing, abuse, and misuse.Citation12 Although provider participation in this REMS is currently voluntary to prescribe these drugs, the FDA and the US Government are pursuing legislation to mandate prescriber education as part of Drug Enforcement Administration licensing or renewal.Citation8,Citation14

The requirements of the class-wide REMS for ER opioids are particularly relevant to primary care providers, who prescribe approximately half of these medicationsCitation3 and thus represent a key point of intervention for risk management and safe use. This article briefly reviews the scope of public health issues related to prescription opioids, describes the class-wide REMS for ER opioids, and answers a few common questions regarding this policy. Understanding this REMS will help clinicians navigate the rapidly evolving landscape for prescribing opioids.

Overdose

Drug overdose deaths have increased each year since 1970, and rates of overdose have increased five-fold since 1990.Citation4 In 2007, for example, more than 27,000 people died from unintentional drug overdose, ranking second only to car accidents as the leading cause of unintentional death due to injury in the US.Citation4 Although rates of overdose have increased for illicit drugs such as cocaine and heroin, the most dramatic increase has been observed with prescription opioid medications.Citation4 Recent epidemiologic data inclusive of patients with chronic noncancer pain, chronic cancer pain, and acute pain indicate an increased risk of overdose and overdose-related deaths in patients prescribed ≥50 mg morphine equivalent per day.Citation15,Citation16 In chronic pain patients receiving ≥100 mg morphine equivalent per day, the risk of overdose death was more than seven times that of chronic pain patients receiving <20 mg per day.Citation15

Misuse and abuse

In 2009, approximately 5 million people reported prescription opioid abuse.Citation5 In persons 12 years or older, the number of first-time abusers of prescription opioids was nearly as common as the number of first-time abusers of marijuana.Citation5 In patients receiving opioids for chronic pain conditions, estimates of the prevalence of abuse in pain management settings range from 12% to 43%.Citation17–Citation20 Furthermore, in primary care chronic pain patients receiving long-term opioid therapy, addiction was four times more likely compared with rates in the general population.Citation21

In this same patient population, 80% of patients report at least one lifetime aberrant drug behavior (eg, request for early refills, unauthorized dose escalation).Citation22 Furthermore, those who engaged in certain aberrant behaviors (purposely oversedating oneself, using opioids for nonpain reasons, escalating dose without authorization, or feeling intoxicated from opioid administration) were approximately 50 times more likely to have opioid addiction.Citation21 Certain patient characteristics may also predict abuse, such as a history of substance use or comorbid psychological conditions, lending weight to the clinical value of utilizing risk assessment prior to initiating opioid therapy.Citation23–Citation27

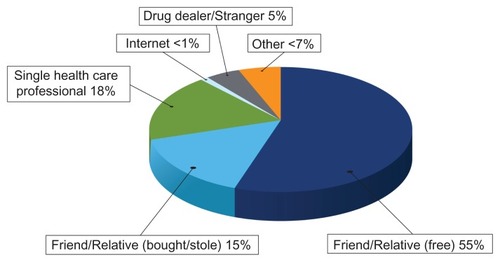

A considerable majority (88%) of persons who abuse prescription opioids obtain them from a friend, relative, or a single health care provider ().Citation5 Furthermore, 18% of all persons who abuse a prescription opioid indicate that the drug was obtained from a single physician. Of the 55% of cases in which the drug was obtained from a friend or family member for free, that friend or relative obtained the prescription from a single health care provider more than 80% of the time.Citation5 Safe and appropriate prescribing practices are therefore fundamental to any risk mitigation effort associated with prescribing opioid analgesics (see Appendix 1). Accordingly, counseling patients on the importance of protecting their medication from theft and never sharing with others is critical.

Figure 1 Sources of prescription opioid analgesics. Data from US Department of Health and Human Services.Citation5

Class-wide REMS for ER opioids

Overview of REMS

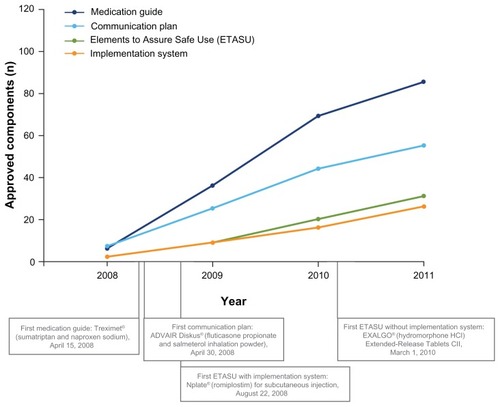

A REMS may be required to ensure that the benefits of a medication outweigh the risks.Citation13 Each REMS may have up to five components: (1) medication guide; (2) communication plan; (3) elements to assure safe use; (4) implementation system; and (5) timetable for submission of assessments ().Citation13,Citation39 Each REMS is individualized and approved with those components that address a product’s therapeutic profile ().Citation13,Citation29

Figure 2 Cumulative approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) components, 2008–2011.Citation29

Table 1 Potential components of a REMSCitation13,Citation39

History and requirements of class-wide REMS for ER opioids

The FDA indicated a need for a class-wide REMS for ER opioids as early as 2009.Citation12,Citation30 In 2010, product-specific, interim REMS were approved for the ER formulation of hydromorphone (Exalgo®; Mallinckrodt Inc, Hazelwood, MO), a novel formulation of controlled-release oxycodone (OxyContin®; Purdue Pharma LP, Stamford, CT), and transdermal buprenorphine (Butrans®; Purdue Pharma LP).Citation29 These programs provide patient education through a medication guide and health care professional training (eg, training on appropriate prescribing practices).Citation29 In April 2011, the FDA officially announced the class-wide REMS for ER opioids, designed to mitigate serious risks of opioid-related adverse outcomes through provider training and patient education (see Appendix 2).Citation12 The release of this policy was closely coordinated with the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy and formed an integral part of the comprehensive Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention Plan.Citation14 The expected requirements of the new class-wide REMS for ER opioids are similar to those of the previously approved REMS for products in this class.Citation12 However, in order to streamline provider and patient education and to decrease the burden on the health care system, all products within the ER opioid class will have the same REMS components.Citation12 These components are discussed in greater detail in the following sections, with regard to the provider and patient perspectives.

Medication guide

A patient medication guide will describe risks (eg, abuse, overdose) and safe use, and stress adherence to the prescribed dosing regimen.Citation12 In addition to specific information on safe and effective use of the particular opioid, the medication guide will include common language for all products in the class.Citation12

The content of the class-wide medication guide may be similar to past ER opioid medication guides and outline symptoms of overdose and the risks associated with physically manipulating or tampering with the product (eg, breaking, chewing, or crushing the tablet), as well as the risk of sharing medications with others.Citation31–Citation33 Patients are also advised to store medications in a safe place to prevent theft or accidental exposure, and to dispose of unused medications properly.Citation31–Citation33 Most current sources suggest flushing unused medications down the toilet, or disposing of them in the trash in an inconspicuous manner.Citation34,Citation35 Furthermore, patients are instructed to report adverse events and are warned of the risks of concomitant use of other central nervous system depressants, alcohol, or illegal drugs.Citation31–Citation33

Elements to assure safe use

Manufacturers will be required to ensure that training is provided to all prescribers of ER opioids.Citation12 The FDA has specified the content of the education program to include: (1) general information for safe opioid prescribing; (2) product- specific information for each opioid within the class; and (3) patient counseling.Citation12 To complement patient counseling, providers will be expected to utilize patient materials, including information on risks, safe use, and storage ().Citation12 The potential content of the training program may be accessed at www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/information/bydrugclass/UCM251595.pdf.Citation12

Table 2 Provider training and patient education, class-wide REMS for ER opioidsCitation12

To implement provider training, manufacturers will fund and collaboratively develop a single set of educational materials applicable to all medications within the ER opioid class. However, training will likely be conducted by an accredited continuing medical education (CME) provider, where participants will be required to complete a subsequent knowledge assessment.Citation12 This approach is intended to facilitate prescriber education and reduce the burden of this program on the health care system.Citation8,Citation12 Because there will be one set of training materials, providers will not have to complete separate educational materials and CME certification for each drug in this class. This may be analogous to the approach of the State of California, which requires all physicians to complete CME credits on pain management, appropriate care, and treatment of the terminally ill.Citation36

Timetable for submission of assessments

Regular and periodic assessments to determine whether the program is meeting the objectives and goals of REMS will be required for the class-wide ER opioid initiative.Citation12 These assessments will provide the FDA and manufacturers with a tool for deciding whether this class-wide REMS should be modified to increase effectiveness.Citation12

Effect of the class-wide REMS

Although training is presently voluntary for health care providers, it may eventually be mandatory for Drug Enforcement Administration licensing or renewal; however, this would require a congressional amendment to the Controlled Substances Act.Citation14,Citation37 Given the current rates of prescription opioid abuse and the need to minimize the serious risks associated with ER opioid formulations, active participation is essential. Although still under discussion between the FDA and manufacturers, there is the potential for providers to complete their class-wide REMS education in coordination with other general CME training in pain management.Citation38

A key challenge of any effort to reduce risk is not overly restricting access for appropriate patients. The FDA has stated its intent to collaborate with the pain management community to ensure continued access to ER opioids after the implementation of the class-wide REMS.Citation8 Ultimately, ensuring the success of these programs with continued access to these important medications will depend on the support of primary care and pain management providers and on collaboration among all stakeholders (ie, FDA, drug manufacturers or sponsors, CME providers, educators, and health care providers).

Acknowledgment

Technical editorial and writing assistance for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Meg Church, Synchrony Medical, LLC, West Chester, PA. Funding for this support was provided by Mallinckrodt Inc, a Covidien company, Hazelwood, MO.

Disclosure

Dr Gudin reports serving as a consultant to Mallinckrodt Inc, a Covidien company, and serving on the speakers’ bureau for Purdue Pharma LP, Pfizer Inc, Johnson & Johnson Inc, and Endo Pharmaceuticals.

Notes

* Not currently marketed in the US.

References

- ChouRFanciulloGJFinePGOpioid treatment guidelines: clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer painJ Pain200910211313019187889

- TrescotAMHelmSHansenHOpioids in the management of chronic non-cancer pain: an update of American Society of the Interventional Pain Physicians’ (ASIPP) guidelinesPain Physician2008special issue 11S56218443640

- GovernaleLOutpatient Prescription Opioid Utilization in the US, Years 2000–2009US Food and Drug Administration2010 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/DrugSafetyandRiskManagementADvisoryCommittee/UCM220950.pdfAccessed January 27, 2012

- Centers for Disease ControlNational Vital Statistics System. Unintentional Drug Poisoning in the United StatesCenters for Disease Control2010 http://www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/pdf/poison-issue-brief.pdfAccessed January 27, 2012

- US Department of Health and Human ServicesSAMHSA. Office of Applied StudiesResults from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Volume 1. Summary of National Findings http://oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k9NSDUH/2k9ResultsP.pdf2009Accessed January 27, 2012

- KatzNPBirnbaumHGCastorAVolume of prescription opioids used nonmedically in the United StatesJ Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother201024214114420504136

- US General Accounting OfficePrescription Drugs, OxyContin Abuse and Diversion, and Efforts to Address the ProblemUS General Accounting Office2003 http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d04110.pdfAccessed January 27, 2012

- US Food and Drug AdministrationQuestions and answers: FDA requires a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for long-acting and extended-release opioidsUS Food and Drug Administration2011 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm251752.htmAccessed January 27, 2012

- MartinsSSStorrCLZhuHChilcoatHDCorrelates of extramedical use of OxyContin versus other analgesic opioids among the US general populationDrug Alcohol Depend2009991–3586718706774

- RederRFOshlackBMiottoJBBenzigerDDKaikoRFSteady-state bioavailability of controlled-release oxycodone in normal subjectsClin Ther1996181951058851456

- ShramMJSathyanGKhannaSEvaluation of the abuse potential of extended release hydromorphone versus immediate release hydromorphoneJ Clin Psychopharmacol2010301253320075644

- US Food and Drug AdministrationPost-approval REMS notification letter http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/UCM251595.pdfAccessed January 27, 2012

- US Food and Drug AdministrationGuidance for Industry: Format and Content of Proposed Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), REMS Assessments, and Proposed REMS ModificationsUS Food and Drug Administration2009 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM184128.pdfAccessed January 27, 2012

- Office of National Drug Control PolicyEpidemic: responding to America’s prescription drug abuse crisis http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/publications/pdf/rx_abuse_plan.pdfAccessed January 27, 2012

- BohnertASValensteinMBairMJAssociation between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deathsJAMA2011305131315132121467284

- DunnKMSaundersKWRutterCMOpioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort studyAnn Intern Med2010152859220083827

- ChabalCErjavecMKJacobsonLMarianoAChaneyEPrescription opiate abuse in chronic pain patients: clinical criteria, incidence, and predictorsClin J Pain1997131501559186022

- KatzNSherburneSBeachMBehavioral monitoring and urine toxicology testing in patients receiving long-term opioid therapyAnesth Analg2003971097110214500164

- ManchikantiLPampatiVDamronKSPrevalence of opioid abuse in interventional pain medicine practice settings: a randomized clinical evaluationPain Physician20014435836516902682

- FishbainDAColeBLewisJRosomoffHLRosomoffRSWhat percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors? A structured evidence-based reviewPain Medicine20089444445918489635

- FlemingMFBalousekSLKlessigCLMundtMPBrownDDSubstance use disorders in a primary care sample receiving daily opioid therapyJ Pain20078757358217499555

- FlemingMFDavisJPassikSDReported lifetime aberrant drug-taking behaviors are predictive of current substance use and mental health problems in primary care patientsPain Medicine2008981098110618721174

- BelgradeMJSchamberCDLindgrenBRThe DIRE score: predicting outcomes of opioid prescribing for chronic painJ Pain20067967168116942953

- ButlerSFBudmanSHFernandezKJamisonRNValidation of a screener and opioid assessment measure for patients with chronic painPain2004112657515494186

- ButlerSFFernandezKBenoitCBudmanSHJamisonRNValidation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R)J Pain20089436037218203666

- Carrington ReidMEngles-HortonLWeberMUse of opioid medications for chronic noncancer pain syndromes in primary careJ Gen Intern Med20021717317911929502

- WebsterLRWebsterRMPredicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk ToolPain Medicine20056643244216336480

- Thalomid (thalidomide) capsules. Risk management planNDA 20-785 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/UCM222649.pdfAccessed January 27, 2012

- US Food and Drug AdministrationApproved risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) December 12, 2011 update. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm111350.htmAccessed January 27, 2012

- Joint Meeting of the Anesthetic and Life Support Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committeehttp://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/AnestheticAndLifeSupportDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM217510.pdfAccessed January 27, 2012

- Medication guideEXALGO (hydromorphone HCl) Extended-release tabletsHazelwood, MOMallinckrodt Inc, a Covidien company2010

- Medication guideBUTRANS CIII (buprenorphine)Stamford, CTPurdue Pharma LP2010

- Medication guideOXYCONTIN (oxycodone hydrochloride controlled-release) TabletsStamford, CTPurdue Pharma LP2010

- US Food and Drug AdministrationMedication disposal: questions and answers http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/EnsuringSafeUseofMedicine/SafeDisposalofMedicines/ucm186188.htmAccessed January 27, 2012

- US Food and Drug AdministrationDisposal of unused medicines: what you should know http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/EnsuringSafeUseofMedicine/SafeDisposalofMedicines/ucm186187.htmAccessed January 27, 2012

- Medical Board of CaliforniaNew laws related to continuing medical education http://www.mbc.ca.gov/licensee/continuing_education_laws.htmlAccessed January 27, 2012

- US Food and Drug AdministrationControlled substances act. Title 21 – Food and drugs; Chapter 13 – Drug abuse prevention and control; Subchapter I – Control and enforcementPart C – Registration of manufacturers, distributors, and dispensers of controlled substances http://www.fda.gov/regulatoryinformation/legislation/ucm148726.htmAccessed January 27, 2012

- US Food and Drug AdministrationFDA opioid REMS meeting with industryMay 16, 2011 http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm258184.htmAccessed January 27, 2012

- FinePGPortenoyRKAd Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation. Establishing “best practices” for opioid rotation: conclusions of an expert panelJ Pain Symptom Manage200938341842519735902

Appendix 1

Case study

Patient: 38-year-old male

Diagnosis: Low back pain

History: The patient has a 6-month history of severe low back pain following a work-related lifting injury. He has failed physical therapy, skeletal muscle relaxants, and epidural injections and is not a surgical candidate. He was switched to an ER opioid from hydrocodone/APAP, as his doses were escalating over time. Despite increases in the ER opioid dose over the last 2 months, he is failing to experience adequate pain relief. The patient has also been prescribed adjuvant medications, including anticonvulsants and antidepressants, and has a prior diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Clinical considerations: Opioid treatment is not appropriate for all patients. It is important for the physician to order appropriate diagnostic tests to evaluate a patient’s underlying pain condition. The physician should consider whether nonopioid therapy is likely to be effective. Patients who have moderate-to-severe pain that affects functioning or quality of life and who present with a favorable risk-benefit balance are most likely to be candidates for opioid therapy.Citation1

All patients being considered for opioid therapy should provide a thorough history, including family history and disclosure of any psychosocial risk factors; patients must also undergo a physical examination and appropriate testing. In every case, this testing must include a thorough assessment of the patient’s risk of substance misuse, abuse, or addiction. A number of brief assessment tools can be used to stratify patients according to risk, including the Opioid Risk ToolCitation27 (ORT) and Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with PainCitation25 (SOAPP®-R). Given that the patient is a young male with low back pain and psychiatric comorbidity, these assessment tools will likely indicate at least a moderate risk for abuse. If a trial of ER opioid therapy is being considered, the physician must evaluate the patient’s recent opioid history. Most doses of ER opioids require that the patient be opioid tolerant, as defined by taking 60 mg/day oral morphine or equivalent for at least 1 week. As the potency of ER opioids differs, the physician should take care to select the appropriate equianalgesic dose and account for incomplete cross-tolerance among opioids. This generally involves a reduction in the equianalgesic dose by 25% to 50% upon conversion to the new opioid.Citation39 Once it is determined that the benefits of continued opioid therapy are likely to outweigh the risks, informed consent should be obtained. The physician should establish treatment goals and an opioid agreement that helps define treatment boundaries and monitor adherence. It is critical that the physician counsel the patient on the risks associated with opioids, such as respiratory depression, concomitant use of other central nervous system depressants, improper storage, and sharing medicine with others. Communicating product-specific information to the patient is also a key element to reduce overall risk. After treatment is initiated, periodic monitoring is important to assess tolerance, changes in symptoms, and abuse-related behaviors. If the patient exhibits aberrant behaviors (eg, lost prescriptions, unsanctioned dose escalations) that are predictive of abuse, the physician may want to consider comanagement or referral to a specialist. The physician should also consider whether discontinuing opioid therapy is a possibility. In summary, when considering a trial of opioid therapy, patient selection, counseling, and ongoing assessment are essential for mitigating risk.

Appendix 2

Commonly asked questions

Which opioid medications fall under the class-wide REMS?

All long-acting and ER opioids will be required to have a REMS under the new class-wide guidelines. These products include Avinza® (morphine sulfate extended-release capsules, CII; King Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Bristol, TN), Butrans® (buprenorphine transdermal system, CIII; Purdue Pharma LP, Stamford, CT), Dolophine® (methadone hydrochloride tablets, CII; Roxane Laboratories, Inc, Columbus, OH), Duragesic® (fentanyl transdermal system, CII; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Titusville, NJ), Embeda®Footnote* (morphine sulfate and naltrexone hydrochloride extended-release capsules, CII; King Pharmaceuticals, Inc), Exalgo® (hydromorphone HCl extended-release tablets, CII; Mallinckrodt Inc, Hazelwood, MO), Kadian® (morphine sulfate extended-release capsules, CII; Actavis Kadian LLC, Morristown, NJ), MS Contin® (morphine sulfate controlled-release tablets, CII; Purdue Pharma LP), Nucynta® ER (tapentadol extended-release tablets, CII; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc), Opana® ER (oxymorphone hydrochloride extended-release tablets, CII; Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc, Chadds Ford, PA), Oramorph® SR (morphine sulfate sustained-release tablets, CII; Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Newport, KY), OxyContin® (oxycodone hydrochloride controlled-release tablets, CII; Purdue Pharma LP), and Palladone®Footnote* (hydromorphone hydrochloride extended-release capsules, CII; Purdue Pharma LP). Generic formulations of the above medications also require a REMS.

As a prescriber of long-acting and ER opioids, can I opt out of REMS?

Although currently voluntary, completion of educational modules and a knowledge assessment will eventually be required in order to continue prescribing these medications.

What are my obligations to patients under the class-wide REMS?

Health care providers will be expected to counsel patients on the risks and safe use of prescription ER opioids (see Appendix 1: Case study). The class-wide REMS will provide educational materials that can be distributed to patients as part of patient counseling. Topics will include adherence and proper administration, safe use and storage of opioids, risks of sharing, risk of tampering (eg, breaking, chewing, crushing), reporting of adverse events, concomitant use with central nervous system depressants, symptoms of overdose, discontinuing opioids, and web links at which additional information may be found.