Abstract

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that often persists throughout life. Approximately two-thirds of patients with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD continue to experience clinically significant symptoms into adulthood. Nevertheless, most of these individuals consider themselves “well,” and a vast majority discontinue medication treatment during adolescence. As evidence concerning the adult presentation of ADHD becomes more widely accepted, increasing numbers of physicians and patients will face decisions about the benefits and risks of continuing ADHD treatment. The risks associated with psychostimulant pharmacotherapy, including abuse, dependence, and cardiovascular events, are well understood. Multiple clinical trials demonstrate the efficacy of psychostimulants in controlling ADHD symptoms in the short term. Recent investigations using randomized withdrawal designs now provide evidence of a clinically significant benefit with continued long-term ADHD pharmacotherapy and provide insight into the negative consequences associated with discontinuation. Because many patients lack insight regarding their ADHD symptoms and impairments, they may place a low value on maintaining treatment. Nevertheless, for patients who choose to discontinue treatment, physicians can remain a source of support and schedule follow-up appointments to reassess patient status. Medication discontinuation can be used as an opportunity to help patients recognize their most impairing symptoms, learn and implement behavioral strategies to cope with ADHD symptoms, and understand when additional supportive resources and the resumption of medication management may be necessary.

Keywords:

Introduction

In the United States, an estimated 4.4% of adults meet diagnostic criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).Citation1 The prevalence of syndromic ADHD is estimated to be lower (between 2.8% and 3.3%) in elderly adults aged 60 years and older from countries in the European Union.Citation2,Citation3 Among adults who received a diagnosis of ADHD in childhood, approximately 65% continued to experience significant ADHD symptoms and functional impairments, although persistence estimates vary widely.Citation4–Citation6 Also, recent findings suggest that, in addition to those who continue to meet full diagnostic criteria for ADHD, a number of adults display persistence of a subset of ADHD symptoms. They continue to experience substantial functional deficits associated with those symptoms.Citation7 The factors that determine ADHD persistence are under active investigation. Recent studies suggest that a childhood ADHD symptom profile, along with psychiatric comorbidity, may be predictive of ADHD persistence. This profile includes predominant inattentive symptoms; more severe symptoms during childhood; and the presence of psychiatric comorbidities, executive function deficits, and some maternal psychopathologies.Citation5,Citation8,Citation9

The behavioral pathology of ADHD is associated with abnormalities in neuroanatomy and neurophysiology in both children and adults.Citation10–Citation15 ADHD appears to be a highly heritable disorder marked by the presence of familial neuropathologic patterns and specific genetic polymorphisms associated with ADHD pathology.Citation16–Citation22 Neuroimaging studies of individuals with ADHD have also identified delayed neurodevelopment, volumetric differences in specific brain areas, and differences in neural activation for tasks when compared to those without ADHD.Citation23,Citation24 Although some of these abnormalities may lessen or resolve as the brain matures, other central neurologic abnormalities persist in adulthood. The functional implications of persistent neurologic abnormalities have not been clearly defined. However, compared with normal controls, cognitive deficits in untreated adults with ADHD appear to persist throughout life.Citation25

ADHD, across the lifespan, is marked by varying degrees of hyperactivity, impulsivity, and attentional symptoms across settings.Citation14 Patients may also exhibit poor emotional control and motivational problems.Citation15 Recommended first-line pharmacotherapy for ADHD in children and adults includes psychostimulants such as methylphenidate and amphetamines, as well as nonstimulant medications such as atomoxetine.Citation6,Citation26–Citation28 The nonstimulants guanfacine extended-release and clonidine extended-release are US Food and Drug Administration-approved for the treatment of ADHD in children and adolescents.Citation29

Need for a long-term approach to adult ADHD management

In the past, ADHD treatment was often routinely discontinued during adolescence; it was unclear whether older patients still exhibited clinically significant symptoms or functional impairments. Moreover, it was uncertain if older patients derived benefits from continued treatment. However, the medical community is now better aware of the changing clinical presentation of ADHD through life transitions and of the need for a longitudinal, developmental approach toward ADHD detection, reassessment, and management.Citation30 During childhood, ADHD can be readily identified by marked overt physical hyperactivity and impulsivity, especially in boys, whereas inattention was often overlooked; in adulthood, such hyperactivity and impulsivity wane and may be internalized as restlessness or impatience, although inattentiveness and disorganization persist and may become the predominant impairing symptoms.Citation31,Citation32 Moreover, with time, ADHD symptoms and impairments take on a progressively more distinct adult presentation.Citation32–Citation35 Impulsivity may be evidenced by sexual promiscuity, financial problems, high job turnover, and/or a short temper; inattention may be evidenced by a high number of traffic citations/accidents, disorganization, chronic tardiness, difficulty finishing projects, forgetfulness, and/or procrastination. Hyperactivity in adults may be experienced as an internal feeling of restlessness or being on edge and expressed outwardly through fidgeting or an inability to sit for long periods of time. Many patients may fail to associate these behaviors with ADHD and may instead consider them to be character traits or part of their personality. Such patients may consider themselves “well” because their childhood symptoms (the reduction of hyperactivity) seem to have resolved; therefore, these patients often discontinue treatment during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood.Citation36

Persisting symptoms in adults with ADHD, although less evident than those in childhood, are associated with relatively greater functional impairments.Citation32 Older adolescents and adults who do not receive treatment for ADHD may suffer lasting consequences related to uncontrolled symptoms and impaired functioning (eg, low occupational/educational attainment, arrest, unintended pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, marital problems, and injury).Citation37 Possibly associated with such functional impairments, the development of certain psychiatric comorbidities (ie, conduct disorders or depression) may also exacerbate poor ADHD symptom control.Citation38,Citation39

The socioeconomic and personal burdens of ADHD experienced by patients, their families, and the community may be mitigated through appropriate long-term treatment.Citation40–Citation42 In addition, in a published systematic review of outcomes, increased substance use disorders or suicidality, compared to untreated ADHD, were not seen with long-term treatment.Citation42 Some evidence suggests that, aside from reductions in core ADHD symptoms, quality of life may be improved with pharmacotherapy.Citation43 Although treatment may not “normalize” functioning to the level seen in non-ADHD individuals,Citation42 large numbers of observational studies worldwide suggest that maintained ADHD treatment over time tends to have a significant beneficial impact on aspects of a patient’s life, including driving, obesity, self-esteem, social functioning, and academic performance when compared to individuals with untreated ADHD.Citation42,Citation44,Citation45 Thus, it is reasonable to examine how the need to continue therapy can be assessed, weighing relative risks and benefits. These risks and benefits include a balance between the economic impact of long-term pharmacotherapy weighed against the potential for lower occupational attainment and wages, potential increased legal and insurance costs, and overall quality of life for patients and family members.

Investigating treatment maintenance and long-term efficacy

Because ADHD persists into adulthood in about two-thirds of patients who have a childhood diagnosis and is associated with significant functional impairments, it would seem that long-term treatment maintenance is necessary and – as evidence shows in many cases – beneficial. In about one-third of these patients, persistent ADHD symptoms may not meet current diagnostic thresholds.Citation5 As with any pharmacotherapy, medications indicated for ADHD are associated with certain risks. In the case of psychostimulants, these include abuse, misuse, addiction, diversion, cardiovascular safety risks such as elevated blood pressure and rare but life-threatening events/cardiac problems (ie, sudden death, myocardial infarction, and stroke); with long-term use, decreases in height and weight have also been a concern with pediatric patients.Citation46–Citation48 However, there is a lack of high-quality evidence from controlled trials in adults regarding the possible benefits of long-term treatment or the consequences of treatment discontinuation.Citation49

Randomized, controlled clinical trials in subjects with ADHD have been conducted in children and have been short-term. Most long-term ADHD treatment trials have been observational and open-label in nature ().Citation50–Citation64 Open-label trials are valuable because they often approximate real-world clinical practice, marked by flexible dosing, to address changes in efficacy or treatment tolerability. In all available open-label trials with durations of 1 year or more, a high level of symptom control has been observed throughout the entire study period, in some cases extending up to 24 months (). Open-label evidence, however, does not rigorously demonstrate maintained treatment efficacy or the consequences of treatment discontinuation.

Table 1 Long-term, open-label investigations of ADHD pharmacotherapy

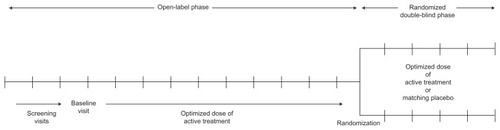

There is a need to more thoroughly examine the value of long-term ADHD pharmacotherapy to support the more widespread use of a lifelong care management approach toward ADHD. Because there are well-established, effective treatments available for ADHD, it is considered unethical to randomly assign subjects to long-term placebo treatment. Adequate subject retention in long-term trials is also problematic. The randomized withdrawal study design is one research approach aimed at addressing these challenges. This design has been used to rigorously investigate the value of continued treatment in other lifelong illnesses, such as major depressive disorderCitation65 and psoriasis.Citation66 For withdrawal trials, subjects with a clinically significant response to active treatment in a prolonged lead-in phase are randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with a placebo or continued active treatment (). For ethical reasons, subjects randomized to a placebo who exhibit significant symptom recurrence and impairments are discontinued from the study and given the opportunity to re-establish active treatment. In this manner, the value of continued treatment may be established; effective treatment is not withheld for an extended period of time. Randomized withdrawal studies can be used to examine maintenance of response, but it should be noted that they do not describe efficacy versus placebos.

Long-term treatment effectiveness in ADHD

A small number of randomized, placebo-controlled withdrawal trials have examined the maintenance of efficacy in adults with ADHD ().Citation67–Citation70 These investigations add to the literature by examining the duration, extent, and nature of symptom control that remain when active treatment is continued compared to when it is discontinued. For these trials, investigators examined ADHD symptom ratings and classroom behaviorsCitation69 or rates and time to ADHD symptom relapse or loss of response, defined as a deterioration of ≥ 2 points on the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement (CGI-I) scale and a 50%–90% decline in ADHD symptoms from baseline.Citation67,Citation68,Citation70

Table 2 Maintenance of efficacy: randomized withdrawal investigations of ADHD pharmacotherapy

In the earliest of these trials, Nolan et al examined the impact of randomized medication discontinuation in a small sample of children (aged 6–18 years, n = 19) with ADHD and comorbid chronic tic disorder or Tourette disorder.Citation69 All subjects were on a stable psychostimulant regimen for at least 1 year prior to enrollment (n = 17 on methylphenidate; n = 2 on dextroamphetamine). Using a two-period crossover design, each subject experienced a randomized, double-blind placebo treatment for 2 weeks and double-blind, continued active treatment for 2 weeks. Analysis of 4-week withdrawal-phase data showed a significant advantage of continued medication treatment compared with a placebo based on all ADHD symptom ratings with mean (SD) Child Symptom Inventory-3R scores of 10.5 (9.7) and 5.5 (6.4) for placebos and active treatment (P = 0.0004), respectively. Core ADHD symptoms and aggression by Mother’s Method for Subgrouping (MOMS) and continuous performance tests, as well as observed simulated classroom behaviors such as time on task and worksheet completion, also demonstrated significant advantages for continued treatment.Citation69

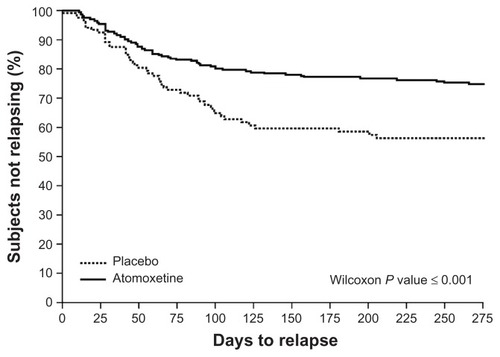

In another randomized withdrawal trial,Citation68 children (aged 6–15 years; n = 416) with ADHD who showed adequate clinical response to the nonstimulant atomoxetine were re-randomized to continued active treatment or a placebo after 12 weeks. At the 9-month study endpoint, 22.3% of subjects who continued with atomoxetine exhibited relapse (defined as symptom return ≥ 90% of baseline in ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS) total scores and ≥ 2 points on the CGI-Severity [CGI-S] scale) compared to 37.9% of those given a placebo (P = 0.002). A Kaplan–Meier analysis further showed that subjects switched to a placebo relapsed in a significantly shorter time than subjects who continued with atomoxetine ().Citation68 Of note was the significant worsening of psychosocial functioning detected among subjects randomized to a placebo, based on the Child Health Questionnaire.

Figure 2 Time to ADHD relapse with atomoxetine versus a placebo.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ADHD-RS-IV, ADHD Rating Scale IV; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions-Severity.

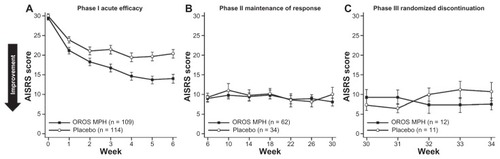

In a more recent trial, Biederman et alCitation67 conducted a three-phase investigation of methylphenidate (MPH) delivered via an osmotic-release oral system (OROS®, Alzo Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA) in adults (aged 19–60 years; n = 223) with ADHD. For the first phase, subjects were randomized to receive either a placebo or clinically optimized doses of OROS MPH for 6 weeks. Subjects who showed an adequate therapeutic response in the first phase (CGI-I of much or very much improved [ie, ratings of 1 or 2] and a reduction in ADHD Investigator Symptom Report Scale [AISRS] score > 30%) were then eligible to continue on to the second phase, in which Phase I treatment (OROS MPH or a placebo) was continued in double-blind fashion for an additional 24 weeks. In Phase III, OROS MPH responders were either re-randomized to a placebo or continued on OROS MPH for 4 weeks; placebo responders were not re-randomized. shows mean AISRS scores for the OROS MPH and placebo groups throughout each phase of the trial.Citation67 During the randomized withdrawal phase (ie, Phase III), subjects who were re-randomized to a placebo showed a gradual small worsening of ADHD symptoms, but these symptoms did not return to baseline severity, whereas subjects who continued with OROS MPH showed a small improvement. No significant changes in AISRS scores were seen during double-blind withdrawal. The investigators noted that a robust therapeutic response among subjects treated with a placebo was indistinguishable from the responses among subjects given OROS MPH.

Figure 3 ADHD symptom scores during acute treatment, maintenance, and randomized withdrawal phases.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AISRS, ADHD Investigator Symptom Report Scale; MPH, methylphenidate; OROS, osmotic release oral system.

No significant difference in relapse rate (defined as a deterioration in CGI-I rating of ≤ 2 points or an AISRS improvement < 15% from baseline) was detected between the subjects who continued active treatment (0%) versus those who were discontinued (18%). Biederman et al propose that, with up to 30 weeks’ treatment with OROS MPH, ADHD symptom control may have allowed subjects to develop more effective, adaptive coping skills.Citation67

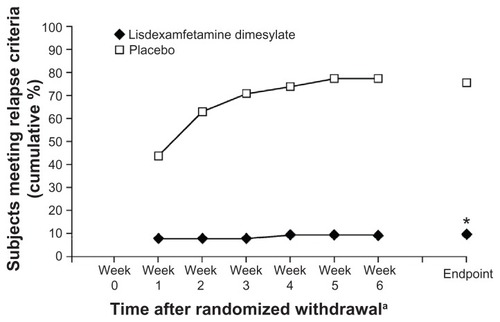

In the most recently published randomized withdrawal study, Brams et al enrolled adults (aged 18–55 years; n = 116) with ADHD who had been receiving a stable dose of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (LDX) (30, 50, or 70 mg/day) in a community setting for at least 6 months with an acceptable safety profile.Citation70 During the first study phase, all subjects received their usual prestudy doses of LDX for 3 weeks. All subjects were then randomized for 6 weeks to receive either a placebo or the same dose of LDX as that given in the open-label phase. At the endpoint of the open-label treatment period, nearly all subjects were rated as not at all or mildly ill based on the CGI-S scale. During the randomized withdrawal phase, symptom relapse (defined as ≥ 50% increase in ADHD-RS-IV score and an increase in CGI-S rating ≥ 2, indicating deterioration of symptom control) was seen in 8.9% of subjects who continued on LDX, compared with 75% of subjects assigned a placebo (P < 0.0001) ().Citation70 For subjects maintained on LDX, least squares (LS) mean changes in ADHD-RS-IV scores from baseline of the randomized withdrawal phase to the endpoint showed only a small change (+1.6 points), compared to larger changes in the placebo group (+16.8 points).Citation70

Figure 4 Percentage of subjects exhibiting relapse with lisdexamfetamine dimesylate or placebo.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ADHD-RS-IV, ADHD Rating Scale IV; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions-Severity.

Conclusion and summary

Despite clear evidence that approximately two-thirds of adults with a childhood ADHD diagnosis continue to experience persistent symptoms and functional impairments, many older adolescent and adult patients believe they are “well” and do not adhere to treatment over the long term. Patients, family members, and some physicians who believe the patient is “well enough” may consider the use of medication to treat ADHD as “unnecessary” due to safety concerns. “Well enough” needs to be operationally defined by the patient and physician. Patients who lack insight into the presence of symptoms may agree that they are still underachieving at school, at their job, and at home even while denying ongoing ADHD symptoms. A growing body of evidence from high-quality clinical trials demonstrates that many patients with ADHD continue to benefit from long-term therapy, whereas discontinuation is often accompanied by a return of symptoms. Continued clinical investigation is needed regarding factors that affect the risk of symptom relapse on discontinuation of pharmacotherapy. Findings will assist clinicians and patients in considering the balance of potential risks and benefits.

Long-term consistent use of medication may increase a patient’s awareness of ADHD impairments independent of the symptoms experienced. When symptom insight is lacking, daily underachievement may encourage the development of effective compensatory skills that persist after medication is stopped.Citation67 On a clinical note, patients may be aware of their symptoms and the resulting daily impairments. These patients may readily adopt behavioral skills to compensate. Patients who have little insight into their ADHD symptoms may acknowledge daily underachievement and be receptive to behavioral techniques. When patients have little insight into their ADHD symptoms and deny daily underachievement, pharmacologic and behavioral treatments are often rejected. Identifying which of these three categories a patient falls into will help a physician determine the best approach when discussing treatment options. Ultimately the discontinuation of medication is likely to lead to a fairly rapid recurrence of the symptoms and worsening of the functional impairments of the disorder. Brams et al demonstrated that, when physicians and patients discontinue medication, follow-up visits within the first few weeks may allow the physician and patient to assess the return of symptoms.Citation70 Such an assessment will allow the physician to understand the degree of insight the patient has gained about changing ADHD symptoms and daily productivity, and may also enhance long-term management of the disorder.

Given that ADHD symptoms – particularly hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms – tend to decrease with age in adolescents and young adults,Citation71 and also based on clinical experience, some patients may be able to successfully discontinue ADHD pharmacotherapy. Brief drug holidays under clinician supervision may help patients become more aware of their symptoms and functioning when they are on medication compared to when they are off. The odds of these holidays being successful may also be increased by timing the discontinuation of medication. A period when environmental demands are reduced or when patients may have increased support from a spouse or family member may limit the impact of ADHD-impaired functioning. Conversely, a patient’s request to discontinue medication during environmentally demanding times is very likely to result in a severe escalation of ADHD impairments and should be delayed for “quieter” times.

It is important for clinicians to discuss the risks/benefits of discontinuing medication with their patients who have ADHD and highlight important symptoms and impairments that should be monitored following discontinuation. However, if the patient wishes to stop medication for reassessment or as an act of asserting control over treatment, the physician needs to remain supportive so as to maintain the therapeutic relationship and not discourage patients’ active participation in managing their health care plan. Performing adequate follow-up allows clinicians to act as a resource upon which patients can rely should they experience a setback or have questions. Encouraging those patients already engaged in psychotherapy or behavioral therapy to continue that form of treatment may help them develop insight into their symptoms and learn behavioral strategies to manage impairments. In addition, participation in therapy may allow patients to see the strengths and limitations of behavioral techniques. If follow-up assessment indicates the return of symptoms or impairments, physicians should facilitate the discussion of resuming treatment. If the patient has not relapsed, it is important to discuss sentinel “red flag” symptoms the patient can easily recognize that may return at a later date. For patients who have successfully discontinued medication, it is crucial to maintain regular periodic follow-up, even if no treatment is prescribed. Patients may be relieved to know their physician remains available when life transitions or stressful events require additional support consisting of a number of options (eg, organizational or goal coaching, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychological counseling, and/or a resumption of pharmacotherapy).

Acknowledgments

Shire Development LLC provided funding to Scientific Communications and Information (SCI) for support in writing and editing this manuscript. Under the direction of the author, Michael Pucci, PhD, an employee of SCI, and Karen Dougherty, PhD, a former employee of SCI, provided writing assistance for this publication. Editorial assistance in formatting, proofreading, copyediting, and fact-checking was also provided by SCI. Thomas Babcock, DO, and Ryan Dammerman, MD, PhD, both of Shire Development LLC, also reviewed and edited this manuscript for scientific accuracy. Although Shire Development LLC was involved in the topic concept and fact-checking of information, the content of this manuscript, its ultimate interpretation, and the decision to submit it for publication in Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management were made by the author alone.

Disclosure

Dr Goodman has received research support and/or consultant fees from Avacat, Cephalon, Consumer Reports, GuidePoint Global, Healthequity Corporation, Lundbeck, Major League Baseball, McNeil, Med-IQ, Novartis, OptumInsight, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Prescriber’s Letter, Pontifax, Professional Studies LLC, Shire Inc, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and the American Physician Institute for Advanced Professional Studies. He has also received honoraria from Medscape, the Neuroscience Education Institute, Temple University, WebMD, and the American Professional Society of ADHD and Related Disorders. The author reports no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KesslerRCAdlerLBarkleyRThe prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationAm J Psychiatry2006163471672316585449

- MichielsenMSemeijnEComijsHCPrevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in older adults in The NetherlandsBr J Psychiatry201220129830522878132

- Guldberg-KjarTJohanssonBOld people reporting childhood AD/HD symptoms: retrospectively self-rated AD/HD symptoms in a population-based Swedish sample aged 65–80Nord J Psychiatry200963537538219308795

- BiedermanJFaraoneSMilbergerSPredictors of persistence and remission of ADHD into adolescence: results from a four-year prospective follow-up studyJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19963533433518714323

- BiedermanJPettyCRClarkeALomedicoAFaraoneSVPredictors of persistent ADHD: an 11-year follow-up studyJ Psychiatr Res201145215015520656298

- PliszkaSAACAP Work Group on Quality IssuesPractice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200746789492117581453

- BiedermanJPettyCREvansMSmallJFaraoneSVHow persistent is ADHD? A controlled 10-year follow-up study of boys with ADHDPsychiatry Res2010177329930420452063

- LaraCFayyadJDe GraafRChildhood predictors of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey InitiativeBiol Psychiatry2009651465419006789

- KesslerRCGreenJGAdlerLAStructure and diagnosis of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: analysis of expanded symptom criteria from the Adult ADHD Clinical Diagnostic ScaleArch Gen Psychiatry201067111168117821041618

- ArnstenAFBerridgeCWMcCrackenJTThe neurological basis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderPrim Psychiatry20091674754

- ValeraEMBrownABiedermanJSex differences in the functional neuroanatomy of working memory in adults with ADHDAm J Psychiatry20101671869419884224

- MakrisNBiedermanJValeraEMCortical thinning of the attention and executive function networks in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderCereb Cortex20071761364137516920883

- Semrud-ClikemanMPliszkaSRBledsoeJLancasterJVolumetric MRI differences in treatment naive and chronically treated adolescents with ADHD-combined typeJ Atten Disord. Epub May 31, 2012

- American Psychiatric AssociationAttention-deficit and disruptive behavior disordersAmerican Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th Edition Text RevisionWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association20008593

- BarkleyRADeficient emotional self-regulation: a core component of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ ADHD Related Disord201012537

- BanaschewskiTBeckerKScheragSFrankeBCoghillDMolecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an overviewEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry201019323725720145962

- FrankeBNealeBMFaraoneSVGenome-wide association studies in ADHDHum Genet20091261135019384554

- PoelmansGPaulsDLBuitelaarJKFrankeBIntegrated genome-wide association study findings: identification of a neurodevelopmental network for attention deficit hyperactivity disorderAm J Psychiatry2011168436537721324949

- BiedermanJPettyCRWilensTEFamilial risk analyses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and substance use disordersAm J Psychiatry2008165110711518006872

- DurstonSFossellaJAMulderMJDopamine transporter genotype conveys familial risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder through striatal activationJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry2008471616718174826

- ShawPGilliamMLiverpoolMCortical development in typically developing children with symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity: support for a dimensional view of attention deficit hyperactivity disorderAm J Psychiatry2011168214315121159727

- CastellanosFXProalELarge-scale brain systems in ADHD: beyond the prefrontal-striatal modelTrends Cogn Sci2012161172622169776

- BushGCingulate, frontal, and parietal cortical dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderBiol Psychiatry201169121160116721489409

- Del CampoNChamberlainSRSahakianBJRobbinsTWThe roles of dopamine and noradrenaline in the pathophysiology and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderBiol Psychiatry20116912e145e15721550021

- BiedermanJFriedRPettyCRCognitive development in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a controlled study in medication-naive adults across the adult life cycleJ Clin Psychiatry2011721111621034681

- Canadian ADHD Resource AllianceCanadian ADHD Practice Guidelines (CAP-Guidelines)3rd edTorontoCanadian Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Resource Alliance (CADDRA)2011 Available from: http://www.caddra.ca/cms4/pdfs/caddraGuidelines2011.pdfAccessed September 13, 2012

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental HealthAttention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The NICE Guideline on Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in Children, Young People and AdultsLondonBritish Psychological Society; Royal College of Psychiatrists2009 Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/ADHDFullGuideline.pdfAccessed September 19, 2012

- KooijSJBejerotSBlackwellAEuropean consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The European Network Adult ADHDBMC Psychiatry2010106720815868

- Intuniv (guanfacine) [package insert]Wayne, PAShire Pharmaceuticals Inc2011

- TurgayAGoodmanDWAshersonPLifespan persistence of ADHD: the life transition model and its applicationJ Clin Psychiatry201273219220122313720

- BiedermanJMickEFaraoneSVAge-dependent decline of symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: impact of remission definition and symptom typeAm J Psychiatry2000157581681810784477

- DasDCherbuinNButterworthPAnsteyKJEastealSA population- based study of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and associated impairment in middle-aged adultsPLoS One201272e3150022347487

- AdlerLKesslerRCSpencerTAdult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v11) Symptom Checklist InstructionsWorld Health Organization (WHO) Workgroup on Adult ADHD. Available from: http://webdoc.nyumc.org/nyumc/files/psych/attachments/psych_adhd_checklist.pdfAccessed October 28, 2012

- BiedermanJFaraoneSVSpencerTJMickEMonuteauxMCAleardiMFunctional impairments in adults with self-reports of diagnosed ADHD: a controlled study of 1001 adults in the communityJ Clin Psychiatry200667452454016669717

- AbleSLJohnstonJAAdlerLASwindleRWFunctional and psychosocial impairment in adults with undiagnosed ADHDPsychol Med20073719710716938146

- McCarthySAshersonPCoghillDAttention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: treatment discontinuation in adolescents and young adultsBr J Psychiatry2009194327327719252159

- GoodmanDWThe consequences of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adultsJ Psychiatr Pract200713531832717890980

- BabinskiLMHartsoughCSLambertNMChildhood conduct problems, hyperactivity-impulsivity, and inattention as predictors of adult criminal activityJ Child Psychol Psychiatry199940334735510190336

- Chronis-TuscanoAMolinaBSPelhamWEVery early predictors of adolescent depression and suicide attempts in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderArch Gen Psychiatry201067101044105120921120

- MatzaLSParamoreCPrasadMA review of the economic burden of ADHDCost Eff Resour Alloc20053515946385

- PowersRLMarksDJMillerCJNewcornJHHalperinJMStimulant treatment in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder moderates adolescent academic outcomeJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200818544945918928410

- ShawMHodgkinsPCaciHA systematic review and analysis of long-term outcomes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of treatment and non-treatmentBMC Med20121019922947230

- CoghillDThe impact of medications on quality of life in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic reviewCNS Drugs2010241084386620839896

- CoxDJMerkelRLKovatchevBSewardREffect of stimulant medication on driving performance of young adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a preliminary double-blind placebo controlled trialJ Nerv Ment Dis2000188423023410790000

- BiedermanJFriedRHammernessPThe effects of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate on the driving performance of young adults with ADHD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study using a validated driving simulator paradigmJ Psychiatr Res201246448449122277301

- Concerta (methylphenidate HCl) [package insert]Titusville, NJMcNeil Pediatrics2010

- Vyvanse (lisdexamfetamine dimesylate) [package insert]Wayne, PAShire US Inc2012

- Adderall XR (mixed salts of a single-entity amphetamine product) [package insert]Wayne, PAShire US Inc2010

- AdlerLDNierenbergAAReview of medication adherence in children and adults with ADHDPostgrad Med2010122118419120107302

- WilensTMcBurnettKSteinMLernerMSpencerTWolraichMADHD treatment with once-daily OROS methylphenidate: final results from a long-term open-label studyJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200544101015102316175106

- AdlerLAOrmanCStarrHLLong-term safety of OROS methylphenidate in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an open-label, dose-titration, 1-year studyJ Clin Psychopharmacol201131110811421192153

- BiedermanJSpencerTJWilensTEWeislerRHReadSCTullochSJon behalf of the SLI 381.304 Study GroupLong-term safety and effectiveness of mixed amphetamine salts extended release in adults with ADHDCNS Spectr20051012 suppl 20162516344837

- FindlingRLChildressACKrishnanSMcGoughJJLong-term effectiveness and safety of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in school-aged children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderCNS Spectrums200813761462018622366

- WeislerRYoungJMattinglyGGaoJSquiresLAdlerLon behalf of the 304 Study GroupLong-term safety and effectiveness of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderCNS Spectr2009141057358520095369

- MattinglyGWWeislerRHYoungJClinical response and symptomatic remission in short- and long-term trials of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderBMC Psychiatry2013133923356790

- FindlingRLCutlerAJSaylorKA long-term open-label safety and effectiveness trial of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol201222532734223083020

- AdlerLASpencerTJWilliamsDWMooreRJMichelsonDLong-term, open-label safety and efficacy of atomoxetine in adults with ADHD: final report of a 4-year studyJ Atten Disord20081224825318448861

- KratochvilCJWilensTEGreenhillLLEffects of long-term atomoxetine treatment for young children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200645891992716865034

- WilensTENewcornJHKratochvilCJLong-term atomoxetine treatment in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Pediatr2006149111211916860138

- SalleeFRLyneAWigalTMcGoughJJLong-term safety and efficacy of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200919321522619519256

- RubinJVinceBSalleeFLyneAYouchaSEffects of long-term open-label coadministration of guanfacine extended release and stimulants on core symptoms of ADHDProceedings of the 163rd Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric AssociationMay 22–26, 2010New Orleans, LA, USA

- GoodmanDWGinsbergLWeislerRHCutlerAJHodgkinsPAn interim analysis of the Quality of Life, Effectiveness, Safety, and Tolerability (QU.E.S.T.) evaluation of mixed amphetamine salts extended release in adults with ADHDCNS Spectr20051012 suppl 20263416344838

- AdlerLASpencerTJMiltonDRMooreRJMichelsonDLong-term, open-label study of the safety and efficacy of atomoxetine in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an interim analysisJ Clin Psychiatry200566329429915766294

- BiedermanJMelmedRDPatelAMcBurnettKDonahueJLyneALong-term, open-label extension study of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with ADHDCNS Spectr200813121047105519179940

- AranoISugimotoTHamasakiTOhnoYPractical application of cure mixture model for long-term censored survivor data from a withdrawal clinical trial of patients with major depressive disorderBMC Med Res Methodol2010103320412598

- LeonardiCLKimballABPappKAEfficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 76-week results from a randomised, doubleblind, placebo- controlled trial (PHOENIX 1)Lancet200837196251665167418486739

- BiedermanJMickESurmanCA randomized, 3-phase, 34-week, double-blind, long-term efficacy study of osmotic-release oral system-methylphenidate in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Clin Psychopharmacol201030554955320814332

- MichelsonDBuitelaarJKDanckaertsMRelapse prevention in pediatric patients with ADHD treated with atomoxetine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200443789690415213591

- NolanEEGadowKDSprafkinJStimulant medication withdrawal during long-term therapy in children with comorbid attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and chronic multiple tic disorderPediatrics19991034 Pt 173073710103294

- BramsMWeislerRFindlingRLMaintenance of efficacy of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: randomized withdrawal designJ Clin Psychiatry201273797798322780921

- SpencerTJBiedermanJMickEAttention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiologyJ Pediatr Psychol200732663164217556405