Abstract

Background

An investigation of safety issues regarding information on contraindications related to cross allergy was conducted to promote clinical awareness and prevent medical errors in a 2200-bed tertiary care teaching hospital.

Methods

Prescribing information on contraindications concerning cross allergy was collected from an information system and package inserts. Data mining and descriptive analysis were performed. A risk register was used for project management and risk assessment. A Plan, Do, Check, Act cycle was used as part of continuous quality improvement. Records of drug counseling and medical errors were collected from an online reporting system. A pharmacist-led multidisciplinary team initiated an intervention program on cross allergy in August 2008.

Results

Four years of risk management at our hospital achieved successful outcomes, ie, the number of medical errors related to cross allergies decreased by 97% (10 cases monthly before August 2008 versus three cases yearly in 2012) and risk rating decreased significantly [initial risk rating: 25(high-risk) before August 2008 versus final risk rating:6 (medium-risk) in December 2012].

Conclusion

We conclude that comprehensive clinical interventions are very effective through team cooperation. Medication use has potential for safety risks if sufficient attention is not paid to contraindications concerning cross allergy. The potential for cross allergy involving drugs which belong to completely different pharmacological classes is easily overlooked and can be dangerous. Pharmacists can play an important role in reducing the risk of cross allergy as well as recommending therapeutic alternatives.

Introduction

A drug allergy is an immunologically mediated reaction that exhibits specificity and recurrence on re-exposure to the offending drug. It occurs in 1%–2% of all admissions and 3%–5% of hospitalized patients.Citation1 Allergic drug reactions account for 5%–10% of all adverse drug reactions and have the potential to cause harm to patients.Citation2 However, allergies can be prevented if the patient’s history of drug allergy is known and coded.Citation3,Citation4 To guarantee safety in medication use, the Joint Commission International requires that a detailed drug allergy history should take into account when doctors prescribe drugs and pharmacists dispense them.Citation5

Furthermore, a patient who is allergic to one specific drug may be allergic to other drugs of similar chemical structure. That is known as cross allergy or cross sensitivity.Citation6,Citation7 Some patients who have a sensitized reaction to medications like nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may have trouble taking any drug belonging to that class, and doctors should try other medications first to avoid cross allergy. For example, acetaminophen which shares the analgesic and antipyretic properties of the NSAIDs, can be used for a patient who is running a high fever but has a history of allergy to NSAIDs. If this step is overlooked, pharmacists can still help detect problems with cross sensitivity if they have a clear understanding of what is being prescribed. Therefore, communication and team cooperation between patients, doctors, pharmacists, nurses, and information engineers are very important for safety assurance.

Overlooking the issue of cross allergy may cause medication errors. However, many doctors, nurses, and pharmacists only focus on cross allergy involving drugs within the same therapeutic class, such as NSAIDs, and may not pay enough attention to cross allergies occurring when, for example, two drugs belonging to a completely different pharmacological class can provoke cross sensitivity as a result of a particular formulation excipient in common.

Four years ago, a serious medication error occurred at our hospital in a female cancer patient with a history of allergy to procaine, a local anesthetic. She was receiving intravenous metoclopramide to avoid possible chemotherapy-induced vomiting. When her daughter was reading the package insert for metoclopramide, she noticed that the drug is contraindicated in patients with a history of allergy to procaine. Immediately a senior clinical pharmacist was consulted. The dispensing pharmacist had not been aware of this type of cross allergy because the two drugs were so different in their therapeutic action. Fortunately, the patient did not experience any adverse drug reaction, and although she forgave our medical staff, the case taught us a profound lesson. Subsequently, a systematic investigation was undertaken of prescribing information on contraindications related to cross allergy for all medications used in our hospital and preliminary interventions were implemented, as discussed here.

Materials and methods

Data collection

This investigation was performed at the Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University. The hospital has 2200 beds, with 2.7 million outpatient visits made annually. A conditional search was performed for each drug using the “New Clinical Drug Reference” software jointly developed by Beijing Kingyee Technology Co, Ltd. and the Chinese Pharmaceutical Association (http://www.medscape.com.cn). An informatics pharmacist recorded any information on contraindications related to cross allergy. Full prescribing information for each medication used in the hospital was reviewed for verification. The cross allergy issue was addressed by retrieving all records from drug counseling, medical consultations, and our online no-fault reporting system which accepts reports of adverse events and medication errors from medical staff. A causality assessment of drug allergy was carried out using the adverse reactions probability scale devised by Naranjo et al.Citation8

Risk register and intervention procedure

A risk register, a tool commonly used in project management and organizational risk assessments,Citation9 was used for prevention of cross allergy. A pharmacist-led multidisciplinary team initiated an intervention program on cross allergy in August 2008. The clinical intervention measures and risk reduction strategies are described in . Risk likelihood was divided into five levels, ie, almost certain (at least weekly, score 5), likely (monthly, score 4), possible (quarterly, score 3), unlikely (may occur every year, score 2), and remote (may occur every 2 years or more, score 1). Consequences were divided into five grades, ie, extreme (score 5), major (score 4), moderate (score 3), minor (score 2), and insignificant (score 1).

Table 1 Risk register for prevention of cross allergy

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed. According to the Hong Kong Hospital Authority risk quantification matrix and risk register documents, the risk rating is derived from likelihood multiplied by consequences, and the value divided into three risk grades (ie, high risk, ≥16; medium risk, 6–15; low risk, 1–5).Citation11 The percentage of questions on cross allergy correctly answered the first time by pharmacists was calculated by correct responses in the first instance divided by all responses.

Results

Contraindication information and descriptions of cross allergy

Descriptions of cross allergy in information on contraindications for drugs within the same therapeutic class are listed in , and include mainly antibacterials, cardiovascular drugs, antitumor drugs, local anesthetics, and endocrine or metabolic agents. Inconsistent descriptions were observed for partial agonists, including organic nitrates, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, local anesthetics, retinoids, 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, and bisphosphonates. Surprisingly, descriptions of cross allergy were also observed to be inconsistent for some drugs with the same generic name but with different pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Table 2 Cross allergy descriptions in information related to contraindications concerning drugs within the same therapeutic class

Prescribing information for certain drugs clearly notes that they are contraindicated in patients who are allergic to drugs belonging to other therapeutic classes. Further, information on contraindications for some drugs which belong to completely different therapeutic classes clearly notes that they are contraindicated in patients who are allergic to structurally similar classes (). Formulation excipients that provoke cross sensitivity are listed in .

Table 3 Cross allergy involving drugs belonging to completely different pharmacological classes

Table 4 Formulation excipients and cross sensitivity

Information on contraindications related to cross allergy for some drugs does not provide direct guidance on safe use of such medication. Four drugs with inadequate information were identified, comprising: donepezil, which is contraindicated in patients who are allergic to piperidine derivatives; diacerein, which is contraindicated in patients who are allergic to anthraquinone derivatives; bifonazole cream, which is contraindicated in patients who are allergic to imidazoles; and doxofylline, which is contraindicated in patients who are allergic to xanthine derivatives.

Effects of intervention

The outcomes of reducing the risk of cross allergy are shown in , and indicate that our four-year comprehensive clinical intervention through team cooperation was very effective.

Table 5 Effects of intervention on prevention of cross allergy

Discussion

Descriptions of cross allergy in information on contraindications for drugs within the same pharmacological class were usually consistent. However, inconsistent descriptions were noted for partial agonists, including organic nitrates, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, local anesthetics, retinoids, 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, and bisphosphonates (). To our knowledge, this is a completely new finding and indicates that doctors and pharmacists should carefully select an alternative for patients who are allergic to certain drugs. For example, oral tretinoin and viaminate, instead of acitretin, can be used for patients with acne who are allergic to other retinoids or vitamin A derivatives. Bupivacaine and tetracaine can be prescribed instead of lidocaine for patients who are allergic to local anesthetics. According to our experience, indepth training in this area is essential.

Even for drugs that share the same generic name but have different manufacturers, it is possible to find different descriptions in the information on contraindications, as noted for oxaliplatin (). The product manufactured domestically is contraindicated in patients who are allergic to platinum derivatives, whereas the information on contraindications for the original imported product contains no mention of cross allergy. To avoid medico-legal disputes between physicians and patients, it is relatively safe to prescribe the original imported product of oxaliplatin instead of domestic oxaliplatin for patients who are allergic to platinum derivatives. An evidence-based meta-analysis indicates that special emphasis should be placed on the role of chemical structure in determining the risk of cross-reactivity between specific agents.Citation12

There are practical differences between the professions of medicine and pharmacy, the most obvious one being that the pharmacist has a more indepth understanding of pharmaceutical chemistry. Theoretically, an educational background in pharmaceutical chemistry means that pharmacists have a relatively higher degree of knowledge about cross allergy than doctors or nurses. Therefore, it is necessary for pharmacists to lead the relevant clinical interventions. Pharmacists can play an important role in detecting problems with cross allergy, and are often at the point of care where decisions about cross allergy can impact selection of medication, so they can assist by recommending alternatives.Citation13

As an example, in 2011 we handled a successful case involving an elderly female patient suffering from a urinary tract infection who visited our hospital and was found to be allergic to a cephalosporin. She had previously received fluoroquinolone therapy, but the therapeutic effect was very poor. Urine bacterial culture results indicated infection with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. The doctor asked a clinical pharmacist for suggestions. Generally, piperacillin-tazobactam and cephamycins, instead of fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, and oxacephems, are used for treatment of mild to moderate infection caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing E. coli.Citation14 However, a patient with a history of allergy to a cephalosporin should not receive fourth-generation cephalosporins, atypical β-lactams (eg, cefoxitin, cefminox, latamoxef), or combination β-lactamase formulations such as piperacillin-tazobactam. Taking into consideration bacterial resistance, the antimicrobial spectrum, and the cross allergy issue, the pharmacist finally recommended intravenous cefmetazole and oral furadantine as alternatives.

Interestingly, no obvious information on cross allergy involving drugs belonging to completely different pharmacological classes appeared in the package inserts. For example, information on contraindications for vancomycin mentions that the drug should not be prescribed for patients who are allergic to glycopeptide antibiotics and aminoglycosides. However, the information on contraindications for aminoglycosides does not note cross allergy related to vancomycin. Metoclopramide is contraindicated in patients who are allergic to procaine and procainamide, whereas the information on contraindications for procaine and procainamide do not note cross allergy in relation to metoclopramide. Almost all doctors, pharmacists, and nurses did not know this important information before August 2008.

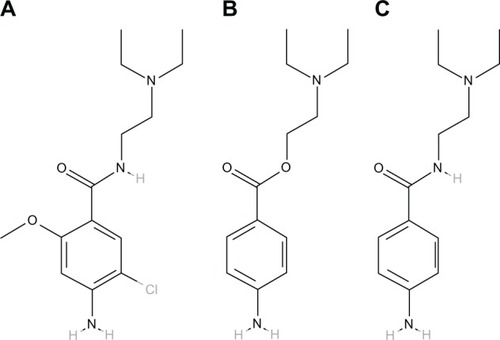

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry names of metoclopramide, procaine, and procainamide are 4-amino-5-chloro-N-[2-(diethylamino)ethyl]-2-methoxybenzamide, 2-(diethylamino)ethyl 4-aminobenzoate, and 4-amino-N-[2-(diethylamino)ethyl] benzamide, respectively, and their chemical structures are shown in . Procaine carries an ester moiety whereas metoclopramide and procainamide carry an amide moiety. Ester and amide are mutual isosteres, so may share the same cross-reactivity pattern, just like amide-type lidocaine and ester-type procaine. A case of immunoglobulin E-mediated anaphylaxis induced by metoclopramide has been documented.Citation15 Therefore, doctors need to take a careful patient history of allergy and select an appropriate medication prior to initiating treatment of nausea and vomiting for patients who are allergic to procaine.

Sometimes information on contraindications gives descriptions of cross allergy related to formulation excipients. However, this aspect seems of less concern to clinicians. Paclitaxel containing Cremophor is contraindicated in patients with a history of allergy to polyoxyethylene castor oil. However, the prescribing information on contraindications for nanoparticle albumin-bound formulations does not note any cross allergy issues. Therefore, this novel formulation of paclitaxel may have certain advantages.Citation16 Some descriptions are so unintelligible and obscure that they lack practical value in guiding safe use of medication, and can cause tension between doctor and patient. For example, Aricept® (donepezil hydrochloride, Eisai Inc, Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA), a drug widely used in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to donepezil hydrochloride or to piperidine derivatives. However, very few hospital staff except pharmaceutical chemists would know which drugs are piperidine derivatives. Such a description may help to understand an allergy that has already happened, but has a limited role in preventing cross allergy, so there is a need to standardize further the information on contraindications related to cross allergy, including specific structural chemical classes, in the future.

A good medication history should encompass all currently and recently prescribed drugs, previous adverse drug events, including hypersensitivity reactions, any over-the counter medications, including herbal or alternative medicines, and adherence with therapy. Documentation of allergies occurring during medical admissions is also very necessary, but hypersensitivity reactions are often poorly documented or not explored in detail, which may lead to potential cross allergy.Citation17 Bruce Bayley et al introduced a medication reconciliation service and recommended identification of allergy as a key contribution at admission and in the follow-up plan at discharge.Citation18 Barton et al reported that involvement of clinical pharmacists leads to improved documentation.Citation19 We introduced a tracer methodology and a work pattern of pharmacist review to address the problem. Collaboration among doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and information engineers is very important. Integration of our clinical information system technology, including computerized entry of physician orders, pharmacy and laboratory information systems, clinical decision support systems, an electronic drug dispensing system, and a bar code point-of-care medication administration system decreased medication errors involving cross allergy. Multidisciplinary teams provide a vital safety net for their patients and colleagues.Citation20

Conclusion

Use of medication can be potentially hazardous if adequate attention is not paid to information on contraindications related to cross allergy. A systematic investigation of this problem was undertaken in a 2200-bed tertiary care teaching hospital. A pharmacist-led multidisciplinary team initiated an intervention program on cross allergy at our institution, and a risk register was used in the management of this project. Four years of experience in risk management at our hospital indicates that comprehensive clinical intervention including team cooperation can play an important role in detecting problems with cross allergy as well as the ability to recommend safer alternatives.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Bureau of Health (2012KYA090).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GomesERDemolyPEpidemiology of hypersensitivity drug reactionsCurr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol2005530931615985812

- RiedlMACasillasAMAdverse drug reactions: types and treatment optionsAm Fam Physician2003681781179014620598

- BhandariSArmitageJChintuMChinnappaSKendrewPThe use of pharmaceuticals for dialysis patients. How well do we know our patients’ allergies?J Ren Care20083421321719090901

- BenkhaialAKaltschmidtJWeisshaarEDiepgenTLHaefeliWEPrescribing errors in patients with documented drug allergies: comparison of ICD-10 coding and written patient notesPharm World Sci20093146447219412703

- Joint Commission InternationalJCI Accreditation Standards for Hospitals4th ed2010 Available from: http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/Accessed Jan 8, 2011

- MyersTMosby’s Medical Dictionary8th edNew York, NYMosby Elsevier2009

- AnovadiyaAPBarvaliyaMJPatelTKTripathiCBCross sensitivity between ciprofoxacin and levofloxacin for an immediate hypersensitivity reactionJ Pharmacol Pharmacother2011218718821897714

- NaranjoCABustoUSellersEMA method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactionsClin Pharmacol Ther1981302392457249508

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Risk register Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_registerAccessed January 28, 2013

- CarterJSmall-scale study using the PDCA cycleGiftRKinneyCToday’s Management Methods: A Guide for the Health Care ExecutiveNew York, NYWiley John and Sons Inc1996

- Hospital AuthorityRisk management in hospital authority Available from: http://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/cad_bnc/125320e.pdfAccessed January 28, 2013

- PichicheroMECaseyJRSafe use of selected cephalosporins in penicillin-allergic patients: a meta-analysisOtolaryngol Head Neck Surg200713634034717321857

- ParkMAMcClimonBJFergusonBCollaboration between allergists and pharmacists increases β-lactam antibiotic prescriptions in patients with a history of penicillin allergyInt Arch Allergy Immunol2011154576220664278

- Rodríguez-BañoJNavarroMDRetamarPPicónEPascualÁExtended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases-Red Española de Investigación en Patología Infecciosa/Grupo de Estudio de Infección Hospitalaria Groupβ-Lactam/β-lactam inhibitor combinations for the treatment of bacteremia due to extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli: a post hoc analysis of prospective cohortsClin Infect Dis20125416717422057701

- KerstanASeitzCSBröckerEBTrautmannAAnaphylaxis during treatment of nausea and vomiting: IgE-mediated metoclopramide allergyAnn Pharmacother2006401889189016940408

- ScriptureCDFiggWDSparreboomAPaclitaxel chemotherapy: from empiricism to a mechanism-based formulation strategyTher Clin Risk Manag2005110711418360550

- FitzgeraldRJMedication errors: the importance of an accurate drug historyBr J Clin Pharmacol20096767167519594536

- Bruce BayleyKSavitzLAMaddaloneTStonerSEHuntJSWellsREvaluation of patient care interventions and recommendations by a transitional care pharmacistTher Clin Risk Manag2007369570318472993

- BartonLFuttermengerJGaddyYSimple prescribing errors and allergy documentation in medical hospital admissions in Australia and New ZealandClin Med20121211912322586784

- RadfordAUndreSAlkhamesiNADarziSARecording of drug allergies: are we doing enough?J Eval Clin Pract20071313013717286735