Abstract

Purpose

The study reported here aimed to identify current sedation practice among general dental practitioners (GDPs) and specialist dental practitioners (SDPs) in Jordan in 2010.

Methods

Questionnaires were sent by email to 1683 GDPs and SDPs who were working in Jordan at the time of the study. The contact details of these dental practitioners were obtained from a Jordan Dental Association list. Details on personal status, use of, and training in, conscious sedation techniques were sought by the questionnaires.

Results

A total of 1003 (60%) questionnaires were returned, with 748 (86.9%) GDPs and 113 (13.1%) SDPs responding. Only ten (1.3%) GDPs and 63 (55.8%) SDPs provided information on the different types of treatments related to their specialties undertaken under some form of sedation performed by specialist and/or assistant anesthetists. Approximately 0.075% of the Jordanian population received some form of sedation during the year 2010, with approximately 0.054% having been treated by oral and maxillofacial surgeons. The main reason for the majority of GDPs (55.0%) and many SDPs (40%) not to perform sedation was lack of training in this field. While some SDPs (26.0%) indicated they did not use sedation because of the inadequacy of sedative facilities.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of the present study, it can be concluded that the provision of conscious sedation services in general and specialist dental practices in Jordan is inconsistent and inadequate. This stresses the great need to train practitioners and dental assistants in Jordan to enable them to safely and effectively perform all forms of sedation.

Background

Anxiety and pain remain a significant barrier to care for many dental patients.Citation1,Citation2 Therefore, sedation and analgesia are often essential because dentistry is often strongly associated with fear, anxiety, pain, and apprehension by both childrenCitation3–Citation5 (defined herein as those aged < 16 years) and adults.Citation6–Citation8 In addition, the management of mentally and physically handicapped patients usually requires these techniques to control anxiety and pain. Consequently, the use of sedation is becoming progressively important as a technique in dental treatment and more practitioners may need to develop their care in this area.Citation9 It has been shown that conscious sedation via oral, intravenous, and inhalational routes is both an effective and safe alternative to general anesthesia (GA) in many cases.Citation10–Citation13 Further, avoiding GA whenever possible and using alternative techniques such as conscious sedation has also been stressed by guidelines in the UK.Citation14,Citation15

Inhalational sedation (IHS), which uses low to moderate concentrations of nitrous oxide in oxygen has many favorable properties that allow it to be used alone for effective sedation or as an atraumatic induction to intravenous sedation (IVS).Citation16 This frequently used technique has a remarkable safety record that is superior to that of the use of local anesthetic alone. Further, IHS together with local anesthesia has also been recommended as an alternative to GA in childrenCitation12,Citation17–Citation19 and in adults undergoing orthodontic extraction and minor oral surgical procedures.Citation20 When comparing previous experiences of dental treatment under GA, the majority of children (80%) preferred IHSCitation18 and showed less postoperative psychological distress when this form of sedation was used.Citation21 The reduction of the number of local anesthetics used, the reduction of the appointment duration for each patient, and the increase in the efficacy of the treatment session were all noted features after using IHS.

IVS, particularly after the introduction of modern oxygen monitoring devices such as oximetry, has many favorable properties rendering it safe for anxiety control. Special skill is required for its administration, but it is suitable for titration. Oral sedation is also an attractive way of sedating patients. It is widely employed because it is simple to teach and learn as well as to administer to patients. Remarkable safety continues to be recorded for the use of anxiolytic, sedative, and anesthetic techniques by appropriately trained dentists in the dental office and other settings.Citation22,Citation23

In Jordan, the use of sedation is characterized by the lack of national guidelines on this practice in dentistry. Jordanian dental practices adopt various international guidelines for the use of all levels of sedation, such as US guidelines.Citation24 These are utilized in parenteral, inhalational, and enteral types of sedation. However, the administration of all levels of sedation – minimal, moderate, and deep – is performed only by independent qualified anesthesia specialists or health care providers who must have the appropriate training, skills, drugs, and equipment that comply with these international guidelines.

Jordanian studies in 2002Citation25,Citation26 and 2005Citation27 looked at the demands placed on sedation services in the country. These studies, which used a modified form of the Dental Fear Survey, reported that dental anxiety (fear of the dentist) was considered a cause of irregular dental attendance in 13.3% of undergraduate students and 10% of school children. These levels of dental anxiety are approaching those found internationally.Citation28 This has raised the need to implement different pain control techniques in Jordanian dental practices, especially in pediatric dentistry. Techniques such as behavioral management and sedation were approved by patients’ families and practitioners in 2006. Further, the Jordan University Hospital (JUH) established a new dental clinic in 2010 designed especially to treat mentally and physically handicapped patients who sometimes require different types of dental treatment. Techniques to control anxiety and pain, such as sedation, may be necessary for such patients. Practitioners in this center may need to develop their knowledge of sedation to best care for these individuals. Additionally, most Jordanian medical centers have adopted developed countries’ guidelines, such as those of the UK or USA, which stress avoiding GA whenever possible and the adoption of alternative techniques such as conscious sedation. As a result, demand for sedation services is expected to rise.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no information in the literature about the practice of sedation in Jordan or in the Arab world. As such, we developed an electronic survey, sent by email to dentists regardless of specialty, to collect data and information on the scope and many aspects of the sedation services performed in dental offices in Jordan. We hope that this information can be compared with data reported for other countries and will be of particular use to those in the dental profession, health care workers, and regulatory agencies. Further, as the number of dentists and specialist dental practitioners (SDPs) in different dental specialties in Jordan has dramatically increased during the last decade, it is hoped that the findings of the present study will shed more light on which sedation practices have been adopted in Jordanian academic and private dental practices, and on whether there is consistency in the instructions relevant to this important dental procedure.

Methods

The study was designed as a questionnaire-based survey and was undertaken from April to December 2009. The email survey, which consisted of a covering letter explaining the purpose of the study and the questionnaire as an attachment, was sent to 1683 general dental practitioners (GDPs) and SDPs who were working in Jordan at the time of the study. Contact details of these GDPs were obtained from a list from the Jordan Dental Association (JDA). The first email was sent in April 2009 and a follow-up email was sent approximately 3 months later to nonresponders or responders who did not answer all questions. No further emails were sent after the second. The questionnaire was anonymous and did not contain any questions that might lead to disclosing the identity of the respondent. Moreover, none of the questions requested any patient identity or confidential patient information. This type of study does not require the ethical committee approval, according to the regulations of the University of Jordan, as no party will be subjected to intervention or harm.

The questionnaire consisted of 17 main questions () and was in English. The questionnaire identified practitioner details and, if respondents indicated they did not use patient sedation, elicited their reasons for this. Those who indicated they did performing sedation in their practices were asked about the age of patients treated (ie, adults/children); the type of sedation technique(s) used; training received for sedation; and issues concerning standards of care, the utilization of sedation services in dentistry, and the need for a plan to promote sedation practices in Jordan (). This promoting plan could involve the provision of education and training programs as well as guidelines to govern the practice of sedation in different places and types of dental practices in the country.

Table 1 Topics investigated to identify the current provision of sedation among general dental practitioners (GDPs) and specialist dental practitioners in Jordan in 2010

Data were analyzed using SPSS (v 17.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and Microsoft® Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). Independent samples t-tests were performed using Statistics Calculator (StatPac, Bloomington, MN, USA) to assess statistical differences between frequencies. Statistical significance was set at a P value of 0.05.

Results

A total of 1683 questionnaires were sent via email to GDPs and SDPs who were working in Jordan at the time of this study. Of these, 1003 (60%) responded. Of these, 142 completed questionnaires were excluded because the replies indicated that the practitioners to whom they were sent were retired, deceased, or working abroad. Thus, 861 completed questionnaires were found usable, although a few questions were not answered in a several questionnaires. Therefore, the number of answers completed for each individual question was used as the basis for reporting the percentage results.

details respondents’ demographic characteristics. In total, 472 GDPs were male, 270 were female, and six did not indicate their sex. Additionally, 73 SDPs were male, 38 were female, and two did not answer the sex question. The mean age of the practitioners (GDPs and SDPs) was 46.5 years (median 48.0 years, range 24.0–70.0 years, standard deviation 12.9 years). Eleven practitioners did not give information about their age.

Table 2 Respondents’ demographic characteristics

Practitioners’ year of qualification with relation to treating patients under sedation is detailed in . Twelve GDPs and two SDPs did not provide information about their year of qualification. It was found that the percentage of SDPs performing sedation was significantly higher than the percentage of GDPs performing sedation across all qualification year periods considered (). However, those SDPs who obtained their qualifications in the 1990s or 2000s performed more sedations than those who obtained their qualifications in the 1960s, 1970s, or 1980s, and this difference was statistically significant (). No statistically significant difference was observed in the proportion of SDPs performing sedation between those who attained their qualification in the 1990s and those who did so in the 2000s (). In addition, when the three earlier categories (ie, the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s) were compared in this regard, no statistically significant difference was found (). No statistically significant difference was observed in the proportion of GDPs performing sedation across all year of qualification categories considered.

Table 3 Respondent practitioners performing sedation in their practices classified by year of qualification (absolute number of respondent practitioners per category or subcategory [%])

Table 4 Comparison between the percentages of general dental practitioners (GDPs) and specialist dental practitioners (SDPs) performing sedation in their practices classified by year of qualification (% followed by absolute number of respondent practitioners per category or subcategory in parentheses)

Table 5 Statistical significance in the difference between the percentages of specialist dental practitioners performing sedation in their practices classified by year of qualification

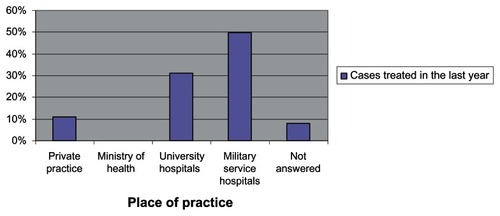

Most practitioners (596 [69.2%]) reported that they worked in private practice (PP), while 81 (9.4%) worked for the Ministry of Health (MH), 102 (11.8%) in university hospitals (UHs), and 67 (7.8%) in military service hospitals (MSHs). Fifteen (1.7%) did not disclose their place of practice.

In total, 73 (8.5%) respondents detailed the different types of treatments related to their specialties that were undertaken under some form of sedation conducted by a specialist and/or assistant anesthetist. Most (63 [86.3%]) were SDPs, while the remainder (10 [13.7%]) were GDPs.

Most GDPs and SDPs who treated patients under sedation worked in MSHs (27 [37%]); together, the next most common places of work were PP and UHs (22 [30.1%]). summarizes the workplaces of all SDP respondents. It shows that none of the respondent practitioners who worked in the MH, whether SDPs, used any form of sedation when treating patients. It also shows that 100% of SDPs working in UHs and MSHs said they performed treatments with patients under sedation, compared with only 25% of SDPs in PP.

Table 6 Distribution of workplace for all specialist dental practitioners (SDPs) performing sedation in their practices (absolute number of respondent practitioners per category or subcategory [%])

In total, 788 (91.5%) respondents did not perform any form of treatment under sedation; most of these (738 [93.7%]) were GDPs, while 50 (6.4%) were SDPs. Practitioners who indicated that they do not perform treatment under sedation were asked to report the main reason for not using sedation. In this regard, the responses varied according to the type (general dental vs specialist) and place of practice (). The most common and important reason reported by GDPs (406 [55%]) for not performing sedation was lack of training in the field. It was also the main reason for SDPs in PP (20/36 [55.6%]), whereas the lack of sedative facilities was regarded by SDPs in the MH (13/14 [92.9%]) as the main reason for not performing sedation. A total of 17 (2.2%) practitioners who indicated they do not perform sedation did not report any main reason for this.

Table 7 Reasons for not performing sedation, as reported by respondent practitioners not performing sedation in their practices (absolute number of respondent practitioners per category or subcategory [%])

The type of sedation used for adults and children by GDPs and SDPs who performed sedation in their practices was also determined. When considering children, IHS was performed by the greatest number of SDPs (39 [61.9%]) and GDPs (4, 40%) practices, followed by oral sedation, which was performed by seven (11.1%) SDPs and two (20%) GDPs. IVS was the least used sedation form with children, with only three SDPs (4.8%) and one GDP (10%) utilizing this type of sedation. For adults, two-thirds (42 [66.6%]) of SDPs treated patients under IVS, while 30 (47.6%) and 21 (33.3%) used oral sedation and IHS, respectively. Five GDPs (50%) performed oral sedation, while three (30%) and two (20%) indicated that they used IVS and IHS, respectively.

In terms of training, most (66 [90.4%]) practitioners who treated patients under sedation in their practices obtained their sedation training as part of their postgraduate study, with only 22 (30.2%) having received some form of undergraduate training in this field.

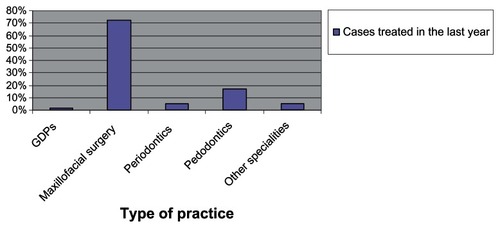

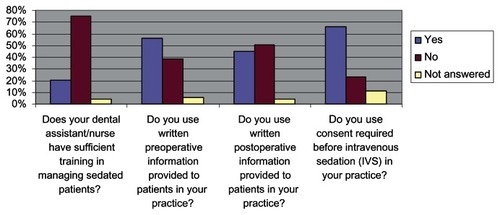

Several questions regarding standards of care in relation to sedation were also included in the questionnaire (). Standards of care were found to vary according to workplace, type of practice, and training. Most (53 [72.6%]) practitioners performing sedation reported that the dental assistants most frequently present during the administration of sedation have insufficient training in managing sedated patients. Surprisingly, 49 (74.2%) of the 66 practitioners who had undertaken some sort of postgraduate training in sedation reported that unqualified dental assistants assisted them with sedation, with only 14 (21.2%) reporting that they receive qualified assistance. Three respondents (4.6%) did not answer this question. Additionally, practitioners performing sedation across all places of practice reported that the majority of dental assistants in their practices were unqualified: in UHs, 19/22 (86.4%); in MSHs, 21/27 (77.8%); and in PP, 13/22 (59.1%). Further, 51/63 (81%) SDPs and 4/10 (40%) GDPs performing sedation in their practices reported being assisted by unqualified dental assistants.

Figure 1 Practitioners’ responses (general dental practitioners and specialist dental practitioners practicing sedation) to four questions dealing with some issues of the standards of care related to conscious sedation (n = 73).

The majority of practitioners performing sedation reported seeking patient consent before IVS (48 [65.8%]) in their practices, which was obtained by the specialist anesthetist or his/her assistant. Consent was sought more frequently by SDPs (43 [68.3%]) than GDPs (5 [50%]), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.2609). When considering the place of practice, the majority of practitioners in MSHs (20/27 [74.1%]) and UHs (17/22 [77.3%]) reported seeking patient consent before performing IVS. In contrast, less than half of PP practitioners (10/22, 45.5%) reported seeking patient consent. These differences were statistically significant (PP vs MSH: P = 0.0466; PP vs UH: P = 0.0360), while the difference between practitioners in MSHs and UHs in this regard was not (P = 0.7966). When the 48 practitioners were asked about the type of consent obtained before the treatment under sedation, oral consent (25 [52.1%]) was cited as the most common form, followed by written consent (17 [35.4%]), with both types of consent (oral and written) being the least used consent format (6 [12.5%]). About half the practitioners reported providing patients with preoperative (41 [56.2%]) and postoperative (33 [45.2%]) information in their places of practice.

When practitioners performing sedation in their practices were asked about a plan to promote the practice of sedation in Jordan, 68 (93.2%) felt there was a need for more education and training courses or a diploma in sedation. Most (72 [98.6%]) also asked for preparation guidelines for IV sedation in private general practices, with 71 (98.6%) feeling that this should be the responsibility of JDA.

To determine the frequency of utilization of different forms of sedation in dental practice, the respondents were asked to report the number of patients they had treated between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2009 (). The results indicated that 3745 sedation cases were completed by all practitioners, with 2720 (72.6%) of these having been treated by oral and maxillofacial surgeons. In terms of place of practice, most of these cases were treated in MSHs (1858 [49.6%]) and UHs (1173 [31.3%]), with only 409 (10.9%) treated in PPs ().

Discussion

The few responses from general practitioners, the exclusion of 142 of completed questionnaires, and the presence of unanswered questions in a few questionnaires were all considered limitations of the study that would make the conduction of any statistical analyses, especially for the GDP group, invalid. However, we felt that a reasonable representation of current conscious sedation practices in Jordan was obtained in that a 60% response rate for this questionnaire was achieved.

Only 1.3% of respondent GDPs and 55.8% of respondent SDPs indicated that they perform treatment under some form of conscious sedation. In total, only 8.5% of respondent practitioners said they perform some form of conscious sedation in their practice; of this 8.5%, 13.7% were GDPs and 86.3% were SDPs. In this study, the percentage of GDPs performing sedation in their practices (1.3%) is much lower than the reported frequency in some UK studies in Grampian,Citation29 Northern England,Citation30 and Wales,Citation31 where 49%, 42%, and 12%, respectively, of primary care practitioners have been reported to perform some form of sedation.

In this study, the distribution of dental practitioners performing sedation by type of dental practice was found to be: general dentistry 13.7%, oral and maxillofacial surgery 42.5%, periodontics 12.3%, pediatric dentistry 17.8%, and other dental specialties 13.7%. In our study, more GDPs and oral and maxillofacial surgeons and fewer periodontists and pedodontists said they performed sedation than those in a study conducted in Illinois in 2006.Citation32

It is interesting to note that all GDPs in our study who treated patients under some form of sedation said that they offer sedation to adults (10) while just over two-thirds offer the service to children (7). Among the GDPs treating adults, oral sedation was used most frequently and this form of sedation was used exclusively by half of those treating adults. IHS was used most frequently in children, and exclusively by 57% of those treating children. It is interesting again to note that more SDPs use sedation with adults (57) than with children (47). Among those SDPs treating adults, IVS was used most frequently and was used exclusively by 73.7% of those treating adults. IHS was used most frequently in children and exclusively by 83% of those treating children with sedation. The reason for this variation between SDPs and GDPs was not clear, but might include differences in the undergraduate and/or postgraduate training received by practitioners.Citation31

All three techniques were widely used by SDPs, and those who reported usage of any form of sedation consistently reported use of at least one of the other forms of sedation in their practice as well. However, GDPs who reported use of one of the three sedation techniques did not use either of the other forms of sedation in their practice. This would indicate that SDPs are more aware of the fact that one technique cannot serve the needs of all patients as well as that access to various techniques will decrease the likelihood of failures.Citation22 However, combining sedation techniques may increase the likelihood of adverse effects, such as respiratory depression and nausea,Citation22 which also seems to indicate that SDPs are more ready to deal with these adverse effects than GDPs. Additionally, among those who perform sedation in their practices, only 4.8% of SDPs and 10.0% of GDPs in this study reported the use of IVS in children, which may indicate that SDPs are more aware of the fact that IVS is rarely justified in children.Citation15,Citation33 However, difference between these two percentages was not found to be statistically significant (P = 0.5054).

The pattern of SDPs’ usage of sedation has been rarely reported in the literature,Citation32 and the figures that have been reported generally relate to sedation practice in primary dental care.Citation29–Citation31 The pattern of sedation usage by GDPs reported in Jordan appears to be similar to a study of the used of sedation by GDPs in Wales,Citation31 which also reported the used of sedation in adults and children separately. It was reported in Wales that, of 87 GDPs, 42.5%, 23%, and 19.5% used IHS, oral sedation, and IVS, respectively, in children. This order of usage was reported to be different for adults in the same study where of the 87 GDPs, 50.6%, 43.7%, and 41.4% respectively used oral, IV and IHS. This similar pattern of usage reported in Wales and Jordan appears to be different to previous UK studies of sedation in primary dental care.Citation29,Citation30 However, these previous studies did not differentiate between the use of sedation in adults and children. FoleyCitation29 and Whiston et alCitation30 found that IVS was most commonly used in the Grampian region and in South Durham, respectively, followed by oral sedation and IHS. Reasons for this variation were attributed to differences in dental school curricula, the availability of training courses in the areas, patient choice,Citation31 the physical status of the patient, patient age, the length and type of procedure, depth of sedation and analgesia, and the experience and preference of the practitioner as well as their location and support available.Citation22

In our study, 91.8% of practitioners treating patients under sedation had undergone some kind of training; in 90.4% of cases, this included courses as a part of postgraduate study, although the type(s) of course undertaken cannot be deduced. This is higher than in, for example, some UK studies, in which 88%,Citation31 75%,Citation30 and 5%Citation29 of practitioners have been reported to have received training. Our high figure could be attributed to respondents in the present study declaring undergraduate or postgraduate training that did not result in a sedation qualification, which was the case in the Welsh surveyCitation31 but was not in some previous UK studies.Citation29,Citation30 Although relevant postgraduate training is a must for practitioners who wish to provide conscious sedation in the UK,Citation15 in Wales, it was reported that at least 29% of practitioners had not met this standard and that 9% had received no training at all.Citation31 In Jordan, there is no clear guidance on practicing conscious sedation from the JDA in relation to the type of training. At least 7% of practitioners in our survey had received no postgraduate training at all. Further, those who had undergone some kind of postgraduate training declared postgraduate training that did not result in a qualification that would enable them to perform sedation by themselves, without the need for the supervision of a specialist anesthetist/assistant. Therefore, at the outset of the study, we expected that a higher percentage of practitioners would indicate that they had not undergone relevant postgraduate training resulting in a sedation qualification.

Although it is difficult to predict what, if any, impact changes to the undergraduate curriculum and the provision of clear JDA guidance will have on future graduates and practitioners,Citation31 the undergraduate curriculum should provide a good introduction to the subject and the JDA should provide clear guidance. This is becoming a more urgent need as the number of practitioners treating patients under sedation with the supervision of specialist anesthetists/assistants has dramatically increased since the introduction of conscious sedation techniques in Jordan (). This was also stressed by 93.2% of practitioners who felt there was a need for more education and training courses or a diploma in sedation, and by almost all of them who felt that the JDA should prepare guidelines on sedation, especially in the PP. Consequently, almost all the practitioners performing sedation indicated that they realized the advantages of preparing clear guidelines, which was expected to overcome the drawbacks of practicing sedation in Jordan. Clear guidelines for the country, as compared with the revised American Dental Association guidelinesCitation34 that are increasingly used in Jordan, would be expected to assist practitioners in the delivery of safe and effective sedation. Such guidelines can be generated by determining standard requirements concerning sedation types; patient types; patient evaluation; preoperative preparation; practitioner training; the skills, drugs, and equipment required; recovery; discharge; emergency management; monitoring; and documentation. Indeed, with the trend of reducing the use of GA, there is a great need to train more practitioners and dental assistants in the field of sedation to enable them to be sufficiently qualified in this field. Additionally, there is a need for clear conscious sedation guidelines to be provided to GDPs and SDPs in Jordan and, preferably, for it to be mandatory to follow these.

Surprisingly, our study suggests that, in Jordan, the dental assistants most frequently present during the administration of sedation by specialist anesthetists in different practices have insufficient training in managing sedated patients – this (as well as the seeking of patient consent for IVS – see the next paragraph) was not apparently affected by the type of sedation training practitioners received. This was not the case in the Welsh survey, in which dentists who reported postgraduate training were also more likely to work with sedation-certified dental assistants and have either another dentist or an anesthetist present while administering sedation. This again stresses the need for more education and training courses on sedation in Jordan, which respondents in our study indicated should be the responsibility of the JDA.

Just less than two-thirds of the respondents in our study indicated that they obtain written consent before IVS, with more SDPs than GDPs and more of those working in MSHs and UHs more than in PP doing so. Again, this indicates the presence of more qualified practitioners working in MSHs and UHs than in PP. In many societies more litigious than Jordan, such as the USA, it is mandatory to obtain written consent before administering IVS. Further, pre-procedural information and counseling improves patient satisfaction, reduces risks, and may be important in obtaining informed consent.Citation35 In our study, written preoperative information was provided to patients by about 56% of practitioners. Increasing the quantity of postoperative information significantly has been found to increase pain relief and patient satisfaction without increasing analgesic consumption.Citation36 Approximately 45% of the practitioners in our study indicated that they provided their patients with written postoperative information. The responsible adult who accompanies the patient at discharge should also have written instructions. A body such as the JDA may wish to prepare standardized documents such as consent forms and pre-/post-sedative information/instructions.

In the present study, the increased demand for sedation services in Jordan was indicated by the finding that respondents reported 3745 cases treated under some form of sedation during the year 2010, with 2720 of these having been treated by oral and maxillofacial surgeons. Assuming no repeat procedures were performed during that year, this suggests that approximately 0.075% of the people in Jordan received some form of sedation in 2010, with approximately 0.054% treated by oral and maxillofacial surgeons. This is a much lower proportion than that in a study conducted in Illinois,Citation32 in which approximately 1% of the population received some form of dental sedation in the year 2005, with about 0.9% treated by oral and maxillofacial surgeons. However, it should be noted that the latter percentage referred to cases treated under some form of dental anesthesia/sedation but which did not receive nitrous oxide analgesia in the 1-year period. When considering place of practice, approximately 0.037% and 0.023% of the people in Jordan received some form of sedation that year in MSHs and in UHs, respectively, with approximately 0.008% treated in PPs. This might be attributed to the increased availability of sedation facilities in MSHs and UHs than in the MH, where the inadequacy of sedative facilities was regarded by SDPs as the main reason for not performing sedation. Again, this may also suggest that practitioners in MSHs and UHs are more qualified to practice treatment under sedation than those SDPs in PP and GDPs in various places of practice, who reported the lack of training in the field of sedation as the most significant reason for not performing sedation ().

Conclusion

Conscious sedation is performed by only 1.3% of GDPs and by just slightly more than half of the SDPs in Jordan who responded to our questionnaire. There is no clear conscious sedation guidance issued by the JDA, or any other medical regulating agencies, for dental practitioners in Jordan to follow. Consequently, the use of conscious sedation techniques shows considerable variation across the profession. Conscious sedation was reportedly not performed by SDPs working in the MH due to lack of sedative facilities, while most GDPs cited lack of adequate training in the field of sedation as the main reason for not performing conscious sedation. Finally, our results indicate that oral and maxillofacial surgeons provide the majority of sedation services in the dental setting in Jordan.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Office for National StatisticsAdult Dental Health Survey: Oral Health in the United Kingdom in 1998; A SurveyLondonThe Stationery Office2000

- KellyMSteeleJNuttalNAdult Dental Health Survey. Oral Health in the United Kingdom in 1998LondonThe Stationary Office2000

- AlvesaloIMurtomaaHMilgromPHonkanenAKarjalainenMTayKMThe Dental Fear Survey Schedule: a study with Finnish childrenInt J Paediatr Dent1993341931988142322

- BediRSutcliffePDonnanPTMcConnachieJThe prevalence of dental anxiety in a group of 13- and 14-year-old Scottish childrenInt J Paediatr Dent19922117241525127

- CuthbertMIMelamedBGA screening device: children at risk for dental fears and management problemsASDC J Dent Child19824964324366960031

- GaleENFears of the dental situationJ Dent Res19725149649664504718

- WardleJFear of dentistryBr J Med Psychol198255Pt 21191267104243

- ScottDSHirschmanRPsychological aspects of dental anxiety in adultsJ Am Dent Assoc1982104127316948026

- DionneRAGordonSMMcCullaghLMPheroJCAssessing the need for anesthesia and sedation in the general populationJ Am Dent Assoc199812921671739495047

- CrawfordANThe use of nitrous oxide-oxygen inhalation sedation with local anaesthesia as an alternative to general anaesthesia for dental extractions in childrenBr Dent J1990168103953982346696

- KaufmanEJastakJTSedation for outpatient dental proceduresCompend Contin Educ Dent19951654624808624986

- BlainKMHillFJThe use of inhalation sedation and local anaesthesia as an alternative to general anaesthesia for dental extractions in childrenBr Dent J1998184126086119682563

- WilsonKEGirdlerNMWelburyRRRandomized, controlled, cross-over clinical trial comparing intravenous midazolam sedation with nitrous oxide sedation in children undergoing dental extractionsBr J Anaesth200391685085614633757

- Department of HealthA Conscious Decision: A review of the Use of General Anaesthesia and Conscious Sedation in Primary Dental CareLondonDepartment of Health2000

- General Dental CouncilMaintaining Standards: Guidance to Dentists on Professional and Personal ConductLondonGeneral Dental Council1997 [revised 2000]. Available from: http://gdc-arf.com/Newsandpublications/Publications/Publications/MaintainingStandards%5B1%5D.pdfAccessed April 1, 2013

- RubinDEisigSFreemanKKrautRNitrous oxide and IV sedation: effect on ETco2 and SPO2Anesth Prog1997441149481973

- PoswilloDEGeneral Anaesthesia, Sedation and Resuscitation in Dentistry: Report of an Expert Working PartyLondonStanding Dental Advisory Committee1990

- ShawAJMeechanJGKilpatrickNMWelburyRRThe use of inhalation sedation and local anaesthesia instead of general anaesthesia for extractions and minor oral surgery in children: a prospective studyInt J Paediatr Dent1996617118695592

- ShepherdARHillFJOrthodontic extractions: a comparative study of inhalation sedation and general anaesthesiaBr Dent J2000188632923110800240

- BergeTIAcceptance and side effects of nitrous oxide oxygen sedation for oral surgical proceduresActa Odontol Scand199957420120610540930

- ArchLMHumphrisGMLeeGTChildren choosing between general anaesthesia or inhalation sedation for dental extractions: the effect on dental anxietyInt J Paediatr Dent2001111414811309872

- MorseZSanoKFujiiKKanriTSedation in Japanese dental schoolsAnesth Prog20045139510115497299

- ZanetteGRobbNFaccoEZanetteLMananiGSedation in dentistry: current sedation practice in ItalyEur J Anaesthesiol200724219820017038227

- ADA Guidelines for Teaching Pain Control and Sedation to Dentists and Dental StudentAs adopted by the October 2007 ADA House of Delegates Available from: http://www.ada.org/sections/about/pdfs/anxiety_guidelines.pdfAccessed April 29, 2013

- Quteish TaaniDSDental anxiety and regularity of dental attendance in younger adultsJ Oral Rehabil200229660460812071931

- TaaniDQDental attendance and anxiety among public and private school children in JordanInt Dent J2002521252911931218

- TaaniDQEl-QaderiSSAbu AlhaijaESDental anxiety in children and its relationship to dental caries and gingival conditionInt J Dent Hyg200532838716451387

- ChanpongBHaasDALockerDNeed and demand for sedation or general anesthesia in dentistry: a national survey of the Canadian populationAnesth Prog200552131115859442

- FoleyJThe way forward for dental sedation and primary care?Br Dent J2002193316116412213010

- WhistonSPrendergastMJWilliamsSASedation in primary dental care: an investigation in two districts of northern EnglandBr Dent J199818483903939604509

- ChadwickBLThompsonSTreasureETSedation in Wales: a questionnaireBr Dent J2006201745345617031353

- FlickWGKatsnelsonAAlstromHIllinois dental anesthesia and sedation survey for 2006Anesth Prog2007542525817579504

- Department of HealthConscious Sedation in the Provision of Dental Care: Report of an Expert Group on Sedation for DentistryLondonStanding Dental Advisory Committee2003

- WeaverJMADA’s sedation and anesthesia guidelines pass: will they be universally accepted?Anesth Prog2008551118327968

- Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-AnesthesiologistsAnesthesiology19968424594718602682

- VallerandWPVallerandAHHeftMThe effects of postoperative preparatory information on the clinical course following third molar extractionJ Oral Maxillofac Surg19945211116511707965311