Abstract

Lobomycosis is a subcutaneous mycosis of chronic evolution caused by the Lacazia loboi fungus. Its distribution is almost exclusive in the Americas, and it has a particularly high prevalence in the Amazon basin. Cases of lobomycosis have been reported only in dolphins and humans. Its prevalence is higher among men who are active in the forest, such as rubber tappers, bushmen, miners, and Indian men. It is recognized that the traumatic implantation of the fungus on the skin is the route by which humans acquire this infection. The lesions affect mainly exposed areas such as the auricles and upper and lower limbs and are typically presented as keloid-like lesions. Currently, surgical removal is the therapeutic procedure of choice in initial cases. Despite the existing data and studies to date, the active immune mechanisms in this infection and its involvement in the control or development of lacaziosis have not been fully clarified. In recent years, little progress has been made in the appraisal of the epidemiologic aspects of the disease. So far, we have neither a population-based study nor any evaluation directed to the forest workers.

Introduction

Lobomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Lacazia loboi. This disease affects primarily the subcutaneous tissue manifested by a chronic granulomatous reaction, full of parasites, in the dermis. Keloid-like lesions are the most common clinical presentation.Citation1–Citation3

With a clear geographic distribution, lobomycosis affects exposed populations of endemic areas in Latin America, with few reports of exported cases.Citation4–Citation6 A new epidemiologic scenario is linked with dolphins that are prone to acquiring lobomycosis. This new context expands the possibility of lobomycosis to every coastal region in which those cetaceans are found, raising the need for clinicians to recognize this emerging fungal infection.

Etiology

The first case report of lobomycosis was done in 1931 by the Brazilian dermatologist Jorge Lobo. This report was about a 52-year-old man who lived in the Amazon region and who presented with sacral lesions resembling keloid. This “new’’ disease was named “blastomicose keloidiana” (keloid blastomycosis).Citation1

Since this first description, several names have been used to describe this entity: Jorge Lobo disease, Jorge Lobo mycosis, Jorge Lobo blastomycosis, amazonic pseudolepromatous blastomycosis, miraip or piraip (in the tupi language), Caiabi leprosy (Caiabi is an Indian tribe located in the state of Mato Grosso), and lacaziosis. Lobomycosis is the correct name for this disease.Citation2

The taxonomy of this fungus is confusing and has changed several times since its first description. Glenosporella loboi was used by Fonseca Filho and Area Leao,Citation3 Blastomyces brasiliensis by Conant and Howell,Citation4 Glenosporosis amazonica by Fonseca Filho,Citation5 Paracoccidioides loboi by Almeida and Lacaz,Citation6 Blastomyces loboi by Langeron and Vanbreuseghem,Citation7 and Lobomyces loboi by Borelli.Citation8

The binomial Loboa loboi described by Ciferri et al is considered a “nomem nundum and illegitimate,” and should not be used.Citation9–Citation11 Most recently, Taborda et al proposed the binomial Lacazia loboi, arguing that previous designations were taxonomically invalid.Citation12

Herr et al, after amplifying the 18SSU ribosomal DNA (rDNA) and 600 bp of the chitin synthetase gene, have contributed to the clarification of the taxonomic enigma of this agent, placing it in the group of the Onygenales order and Ajellomycetaceae family.Citation13 Similarities between Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and L. loboi put both species in the same taxonomic complex.Citation2,Citation14 Electronic microscopy study showed similarities concerning cellular structure, although differences in reproduction could be demonstrated.Citation15 Immunological similarities between these species have been described.Citation2,Citation11,Citation16–Citation19 Phylogenetic data strongly support the placement of L. loboi in its own species, separate from all known P. brasiliensis phylogenetic species.Citation20

Regular round-shaped yeasts, isolated or in a chain, are the typical presentation of L. loboi in tissues. The size is approximately 6 × 13.5 × 11 μm, with a birefringent membrane and thick wall containing melanin. Reproduction with simple gemmulation, without exporulation, forms the blastoconidia and leads to the typical rosary bead figures.Citation19,Citation20

The impossibility of cultivating the species L. loboi in culture medium is believed to be an adaptation to the parasitic life of the fungus.Citation20 Inoculations have been described in several animals, including hamster testis,Citation21 hamster cheek pouch,Citation22 armadillo (Euphractus sexcinctus), and turtles, but have produced no satisfactory response in mice.Citation23 Culture in chorioallantoic membrane of embryonic chicken eggs and disease after accidental inoculation in humans has also been described.Citation24,Citation25

Pathogenesis

Lobomycosis can cause primary skin infection in humans and dolphins. Trauma is considered the pivotal event. It is believed that L. loboi, which is saprophytic in soil, vegetation, and water, must be inoculated within the dermis to start an infection.Citation26 Some speculate transmission is related to insect or animal inoculation based in reports in which the symptoms occurred after snakebite, stingray accident, or insect bite.Citation27

In the dermis, the fungus starts its proliferative phase within the macrophages.Citation28 By direct influence of the microorganism, transforming growth factor β1 concentration increases. Transforming growth factor β1 is a cytokine produced by macrophages and Th3 lymphocytes and is considered to be a potent immunosuppressive molecule. This cytokine is expressed in histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells and diffuses in the inflammatory infiltrate of patients with lobomycosis.Citation29 It suppresses the phagocytic activity of macrophages and has the capacity to inhibit nitric oxide and gamma interferon expression, consequently impairing the cell-mediated immunity.Citation29–Citation33 In addition, this cytokine can promote the proliferation of CD8 T lymphocytes, stimulating the production of immunoglobulin A antibodies by plasma cells and the process of fibrosis, including the formation of extracellular matrix, contributing with the keloid-like appearance of the clinical lesion.Citation23,Citation31,Citation34

Another cytokine found in the dermis of lobomycosis patients is interleukin 10 (IL-10). Together with transforming growth factor β1, IL-10 acts by inhibiting the cellular immune response and, as a consequence, the activation of macrophages.Citation29 The negative effect on cellular immunity could create a localized environment of specific immunodeficiency, as demonstrated by the absence of a response to dinitrochlorobenzene, as well as delayed responses to Staphylococci, Streptococci, Trichophyton, and Candida antigens.Citation28,Citation35 Immunoglobulin and complemented characterization of the lesions are in agreement with the findings of a T helper 2 profile.Citation36

Quaresma, in 2010, created the hypothesis that Langerhans cells could modulate local infection, helping the fungus to evade the immune system.Citation37 The leukocyte and neutrophil functions, as well as complement activity, are preserved in patients with Jorge Lobo’s disease.Citation38,Citation39 Studies of humoral immunity in patients with lobomycosis exhibit a Th2 cytokine profile with increased production of IL-4 and IL-6 and lower production of IL2.Citation28,Citation35,Citation40 Some authors believe in a protective factor caused by the presence of the melanin within the fungus wall.Citation41

In spite of all defensive mechanisms, fungal viability indices range from 20%–50%.Citation42 The mechanisms that lead to in situ L. loboi cell lysis are still unknown. It is possible that CD8 T lymphocytes or natural killer cells exert a cytotoxic effect by lysing macrophages infected with the fungus through a mechanism dependent on exocytosis of granules containing perforin and granzyme, similar to what occurs in other infectious diseases.Citation43–Citation45 Another possibility is the participation of the complement system, as deposits of the C3c component on the fungal cell wall in histological sections obtained from patients with the mycosis could be demonstrated.Citation36

Molecular techniques identified eight antigens of P. brasiliensis (29–108 kDa) in sera of infected hosts with L. loboi.Citation46 Mendoza et al, in 2008, used specific L. loboi antigens extracted from mice as well as from dolphins with Jorge Lobo’s disease. They demonstrated that an immunodominant antigen with a high molecular weight of ~193 kDa was recognized by antibodies in the serum, suggesting that the antigenic proteins of L. loboi have much higher molecular weight than the counterpart, gp43, of P. brasiliensis.Citation47

Preserved cellular immunity is probably necessary to hinder the progression of the disease, or in some cases, prevent its appearance. Nowadays it is not possible to identify sub-clinical lobomycosis due to lack of a specific and reliable antigen. Lobina, once used for this purpose, lacks specificity and may present cross reaction with other agents such as P. brasiliensis and some mycetoma agents. Because there is no way to correctly identify cases of lobomycosis infection, at this time it is not possible to know the exact number of infected people or the percentage of them that present with the disease.Citation48

After the proliferative phase in the dermis, there is a possibility of a dissemination phase through lymphatics. Reports of regional lymph node enlargement and lymphatic spread of the disease have both been described, and supports this hypothesis. It is not known, however, how many patients evolve with lymphatic disease.Citation49

Contiguous dissemination and/or autoinoculation have also been described. Repetitive traumatism cannot be discarded in many cases because the patient is still under the epidemiologic risk of being infected. There is only one reported case of systemic lesion caused by possible L. loboi where the testicle was involved, probably after hematogenous spread. Human transmission has never occurred, although experimental autoinoculation and accidental inoculation both have been reported.Citation24,Citation25,Citation50

Epidemiology and geographic distribution

The biogeographic complex of L. loboi is situated in areas of forests with dense vegetation and large rivers. The annual rainfall is usually more than 2,000 mm/year, with an average temperature of 24°C and relative humidity of 75%. Those climatic characteristics are found in the tropical region of the Amazon basin, where most of the cases have been described.Citation51

Since its first description, “keloid blastomycosis” was believed to be specific to areas of forests with high heat and humidity. Until that time, it mainly affected male forest workers.Citation52 Jorge Lobo’s disease was relatively frequent in the Amazon region,Citation53 with most cases originating from the Brazilian Amazon region.Citation54 By 1950, the first case of lobomycosis was described in Central America, and reports of the disease in Central and South America have been published regularly ever since. By 2000, only 3 of 465 human cases had been published outside the Amazon basin.Citation23

The ecological niche of the fungus is expanding. The identification of the disease in dolphins was first made in the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) from the Atlantic coast of the United States at the Gulf of Mexico;Citation55 it is also endemic in Florida coastal estuaries. The disease also affects the Guyana dolphin (Sotalia guianensis) from the Suriname River.Citation55–Citation60 Reports of photographic evidence of lobomycosis-like disease in dolphins from the Indian Ocean, the Japanese coast, the Brazilian South coast, the western Pacific, the Africa coast, the European coast, and the North Carolina coast show the regions where lobomycosis can be found.Citation57,Citation59,Citation61–Citation63

The dolphins of the endemic areas, botos (Inia geoffrensis) and tucuxis (Sotalia fluviatilis), that inhabit the Amazon and Orinoco river basins of Brazil and Venezuela, respectively, where the human disease is endemic, do not present with lobomycosis.Citation58

To date, occurences of Jorge Lobo’s disease in humans were reported in nine countries of South America (Brazil, Colombia,Citation26,Citation64,Citation65 Suriname,Citation66 Venezuela,Citation58,Citation67–Citation71 Guyana, French Guiana,Citation72–Citation74 Ecuador,Citation75 Peru,Citation76–Citation78 and BoliviaCitation79), three countries of Central America (Panama,Citation80,Citation81 Costa Rica,Citation82 and Mexico), and imported cases in the United States,Citation83 Canada,Citation84 France,Citation85 Netherlands,Citation86 Germany,Citation87 Greece,Citation88 and South Africa.Citation69

For some time, it was believed that genetic predisposition was crucial for acquiring the disease once it affected preferably indigenous populations.Citation89,Citation90 Baruzzi et al were the first to demonstrate the link between geography and lobomycosis. The authors showed that after transferring the Caiabi Indians from the Tapajos River region to the Indian Xingu National Park, there were no more new cases of lobomycosis detected. The same studyCitation89 incisively reinforces the importance of location in the occurrence of lobomycosis.Citation89,Citation91,Citation92

Lobomycosis can now be included in different epidemiologic contexts: occupational or recreational infection in endemic areas, occupational hazard for professions dealing with dolphins, and emerging infection in many coastal regions. This disease is classically an opportunistic infection that affects vulnerable populations living and working in forest areas, especially extrativists forest workers, river dwellers, and the Indian population. Nowadays, there is an increasing interest in products and substances derived from the forest. The need to preserve the native vegetation during extraction leads to strategies of sustainable harvesting for a new market. Those workers must be protected from all the diseases related to the forest environment, including lobomycosis.Citation65,Citation89,Citation91,Citation93–Citation97

Since the description of natural disease in dolphins and the report of a zoonotic transmission in an aquarium worker after contact with a sick dolphin,Citation86 lobomycosis can be included in the list of zoonotic mycosis.Citation61 It is an occupational hazard for veterinarians, marine biologists, and others who handle dolphins during health assessments, rescue operations, and rehabilitation efforts of stranded or injured animals. Direct and indirect human contact with dolphins have expanded because of the increased number of dolphins under managed care in aquarium and commercial exhibitions, as well as in swimming-with-dolphins programs for recreational or therapeutic benefit.Citation86,Citation87

Zoonotic transmission from dolphins is presumed, the clearest evidence of which was described in an aquarium attendant with a hand lesion that occurred after managing a sick animal.Citation86 Other cases in which zoonotic transmission is suspected have been published. The first case was a patient from Suriname,Citation98 an area where lobomycosis occurs in Guiana dolphins (S. guianensis) that inhabit the Suriname River estuary,Citation99 and the second case developed in a young man from South Africa who was an avid swimmer and diver.Citation100 The third occurred in a fisherman from Venezuela who developed lesions on the ear after being pierced with a fishing hook in a coastal area where an affected dolphin was observed.Citation67 Most recently, lobomycosis was diagnosed in a female farmer with hypoglobulinemia and common variable immunodeficiency and hepatitis who lived on the Greek coast.Citation88

A report by a dermatologist who suffered an accidental laceration during a biopsy procedure of a dolphin with lobomycosisCitation101 without subsequent development of lobomycosis suggest that transmission from dolphins to humans, even through direct inoculation, is unlikely in immunocompetent individuals.

Morphologically, the organisms found in dolphin differ when compared with human L. loboi. They are smaller and have morphometric and ultrastructural differences in the cell wall.Citation102 Molecular sequencing of rDNA from an infected dolphin showed a novel sequence related more closely to P. brasiliensis than to L. loboi of human origin.Citation103

This recent evidence is supported by an earlier study that showed that ribosomal RNA gene sequences from an infected dolphin were 97% homologous with P. brasiliensis.Citation57 In contrast, serum from an infected dolphin recognized an immunodominant 193-kDa antigen from an extract of human L. loboi more strongly than the gp43 antigen of P. brasiliensis in western blotting analyses.Citation47

Experimental inoculation of a laboratory scientist with yeast-like cells from a human patient, as well as a report of an accidental transmission of lobomycosis in another laboratory scientist who collected and purified fungal cells from human skin biopsies,Citation50 imply that under unusual circumstances, Lacazia of human origin can be transmitted to other humans.Citation24

The epidemiologic data of lobomycosis in endemic areas is unknown. The largest casuistic comes from Acre, Brazil. A retrospective study identified 249 patients diagnosed with lobomycosis in a period between 1998 and 2008; the calculated prevalence was 3.05/10,000 inhabitants. This number is probably underestimated because the population at epidemiologic risk lives in the forest, with difficult access to the health system.Citation104

Clinical presentation

After an unknown incubation period, estimated to be between 1–2 years, lobomycosis affects predominantly exposed areas (pinna in 38%, upper limbs in 28%, lower limbs in 22%) of adult males who develop activities in the forest ().Citation2,Citation105 Localized disease represents 61% of the cases.Citation104 The time between the first signs of the disease and the diagnosis varies from months to decades. In the Woods article, the average time was 19 years.Citation83

The initial lesion is a papule: depending on the level of the trauma, it may be superficial or deep. Slow progression in a period of months to years leads to the formation of a plaque or nodule. The primary lesion is covered by smooth and shiny intact skin. The surface color varies from the patient’s color to erythematous-brownish or red-wine, with or without telangiectasia. Those characteristics give the typical presentation a fibrous appearance, resembling a scar or a keloid ().Citation23

Figure 2 Typical primary fibrous appearance, with nodular plaques covered by smooth and shiny skin, with small exulcerated areas and visible telangiectasias.

Chronic by nature, localized in trauma-prone areas, and exposed to a moist environment, the clinical lesions may suffer modifications leading to a more polymorphic clinical picture. Dyschromic changes are commonly described, varying from hyperpigmentation to hypopigmentation and achromia.Citation7,Citation9,Citation23

Ulcers are believed to be secondary to trauma, especially after maceration that occurs in the rainy season. Deeper lesions are probably related to recent inoculated lesions and are described as infiltrative. Continuous growth may bestow an exophytic appearance in some cases ().Citation13,Citation23,Citation93

Figure 3 Local destruction of the left auricle, presenting exophytic erythematous-brownish lesion, with a pedunculated aspect and telangiectasias.

Some of these lesions may present with a wart-like surface leading to verrucous lobomycosis. This clinical picture typically affects the lower limbs and imposes differential diagnosis with chromomycosis.Citation23,Citation106

Gummalike lobomycosis is rarely seen. It is described as occurring in macular lesions that evolve with turgid borders, followed by pustules and finally an exudation of a thick yellow material. Scar tissue eventually develops. This phenomenon can occur several times in the same lesion and is associated with spontaneous resolution, an extremely rare event.Citation96 There is only one report of spontaneous resolution, accompanied by cicatricial areas without fungal elements after an episode of lobomycosis.Citation93

Emergence of new wounds around the index lesion raises questions about autoinoculation or local lymphatic dissemination, although continuous exposure cannot be discarded. This picture may lead to confluent lesions forming big plaques or the presence of hundreds of lesions. Autoinoculation has been documented in a case where the donor site for skin graft evolved with a lobomycosis lesion; contaminated material was the probable cause.Citation106 Local lymphatic spread of the disease has been reported with estimated occurrence of 10% to 25%.Citation49,Citation107 In one case, the testicle was affected, and hematogenous spread of the fungus was implicated as the cause.Citation26

Symptoms are rarely associated with lobomycosis lesions. Pruritus and dysesthesia are symptoms more often described in extensive cases. The progressive nature may lead to deformation, causing functional and aesthetic concerns.Citation104 Carcinomatous degeneration is a possible and feared complication ().Citation104,Citation108

Classifications have been proposed and are essentially based on clinical aspects of the disease. A morphologic classification subdivided the cases into infiltrative, keloid-like, in plaques, verruciform, and ulcerated forms ().Citation109,Citation110 A classification based on the immunologic response to the fungus was proposed by Machado: hyperergic (macules and gumma) and hypoergic (keloid-like).Citation111 An operational approach proposed one classification based on the distribution of the disease as follows: localized or isolated disease, multifocal disease (restricted to an anatomical area), or disseminated disease (more than one anatomical segment). This classification is aimed to program the therapeutic strategy.Citation104

Diagnosis

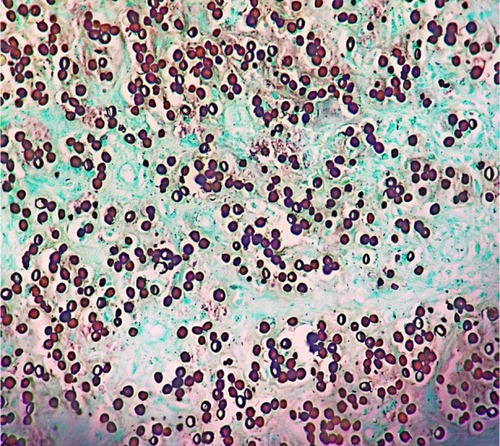

Diagnosis is primarily based on clinical aspects of the lesion. It should be confirmed by identifying the numerous agents within the lesion. Round and oval yeast-like structures with regular size, between 6–12 μm, and a birefringent membrane are found in the dermis. The fungal structures may be found isolated or with a simple gemmulation; the typical catenular or Rosario beads distribution is commonly found (). Direct examination by scraping the lesions is the simplest way to visualize the fungus. Alternatively, techniques such as vinyl adhesive tape or exfoliative cytology may also be used.Citation112–Citation114

Figure 6 Histological section showing round and oval yeast-link structures with birefringent membrane, with isolated and Rosario beads distribution, commonly found in Jorge Lobo’s disease.

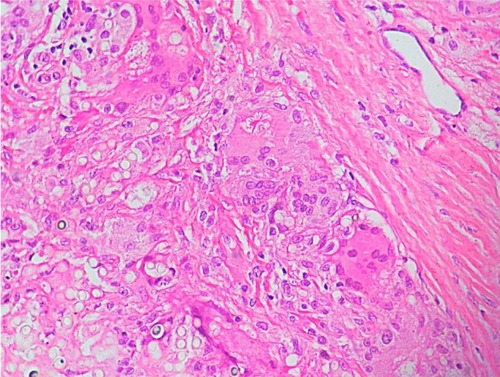

The histopathology of the lesions sent for biopsies are obtained by routine staining with hematoxylin-eosin, with the agents better visualized with silver stains. The characteristic histopathologic picture is composed by a dense and diffuse histiocytic infiltrate of the dermis, with an overwhelming number of parasites. Occasionally, the Unna band may be observed.Citation26

The epidermis is typically presented with rectification of the rete ridges or atrophic areas above a thin Grenz band.Citation115 Acanthotic areas with the presence of hyperkeratosis, spongiosis, and neutrophil collection may be observed.Citation113 Those changes are probably elicited by the presence of the fungus in the epidermis.Citation116 Hyperplastic infundibulum is associated with transepidermal elimination of the fungus.Citation113 This phenomenon has already been documented and is the basis for the vinyl adhesive tape technic.Citation112

The dense histiocytic dermal infiltrate is composed of a large number of epithelioid, multinucleated, and Langhans cells with or without the presence of granulomas (). Sometimes, aggregates of large xanthomatous histiocytes with clear cytoplasm or finely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, without parasites within, can be found. Those are called pseudo-Gaucher cells.Citation113 A great number of fungal structures are found within the macrophages or in the dermis. Lymphocytes are present in discrete to moderate numbers, with a predominance of CD4 T lymphocytes and a CD4:CD8 ratio of approximately 3:2. Plasma cells and B lymphocytes are less frequent than T lymphocytes, with natural killer cells always present.Citation29,Citation117 Neutrophils are rarely found and are associated with ulcers or fungus within the epidermis. Fibrosis is a striking feature, and Asteroid bodies may be seen.Citation23

Treatment

The ideal treatment is wide surgical excision. It is worth noting that instruments contaminated during operation can lead to reinfection.Citation106

There is no optimal drug treatment for cases in which surgery is contraindicated or for disseminated infection. The only successful oral treatment with complete response was reported in a dolphin, using myconazol.Citation118 Many antifungal agents have been tested with unsatisfying results: ketoconazole,Citation79,Citation119,Citation120 amphotericin B,Citation121 sulfa compounds,Citation122 and 5-fluorocystosineCitation123 all have been proved inefficient. Itraconazole has been shown to be partially effective and can be used as an adjuvant to prevent recurrence of surgically removed lesions.Citation124 Itraconazole with cryosurgery has been successfully used to treat relapse of lobomycosis.Citation123,Citation124 Clofazimine, with dosages of 100–300 mg daily for up to 2 years, has been used in some reports, with unsatisfactory results.Citation125–Citation127 Interestingly, as per the experience of the Leprosy Elimination Programme of Acre, in Brazil, patients with lobomycosis and concurrent leprosy have been shown to respond to multibacillary therapy with reduction of pruritus and size of the mycotic nodules.Citation104

The new azoles with expanded spectrum may prove to be efficacious. Posaconazole has been used for 24 months and has achieved the cure of the lesion without remission in 5-year follow-up.Citation78

Because of the recurrence of lesions, in cases of surgical removal, patient follow-up is necessary for a long time before considering it cured. To date, there is no efficient drug treatment, and surgical removal is the most-used therapeutic procedure.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LoboJOUm caso de blastomicose produzido por uma espécie nova, encontrada em RecifeRev Med Pernambuco19311763765

- LacazCDPortoEMartinsJECHeins-VaccariEMde MeloNTDoença de Jorge LoboTratado de Micologia Médica Lacaz9th edSão PauloSarvier2002462478 Brazilian

- Fonseca FilhoOArea LeãoAEContribuição para o conhecimento das granulomatoses blastomycoides: o agente etiológico da doença de Jorge LoboRev Med Cirurg Brasil194048147158

- Fonseca FilhoOArêa LeãoAEContribuição para o conhecimento das granulomatoses blastomicoides. O agente etiológico da doença de Jorge LoboBol Acad Nac Med Rio de J19401124253 Brazilian

- Fonseca FilhoOGlenosporella loboiFonseca FilhoOParasitologia Médica Parasitos e Doenças Parasitárias do HomemRio de JaneiroGuanabara Koogan1943703725 Brazilian

- AlmeidaFPLacazCSBlastomicose “tipo Jorge Lobo.”An Fac Med S Paulo1948194924537

- LangeronMVanbreuseghemRLa blastomycose chéloidienne ou maladie die Jorge LoboLangeronMVanbreuseghemRPrécis de Mycologie. DeuxièmeParisMasson1952490491 French

- BorelliDLobomicosis: nomenclatura de agente (revisión critica)Med Cutanea196832151156

- FonsecaOJMLacaz CdaSEstudo de culturas isoladas de blastomicose queloidiforme (doença de Jorge Lobo). Denominação ao seu agente etiològicoRev Inst Med Trop São Paulo1971132252515132384

- AzevedoDECamposSCarneiroLSCiferriRAdvance in the knowledge of the fungus of Jorge Lobo’s diseaseJ Trop Med Hyg195659921421513368252

- SilvaMEKaplanWMirandaJLAntigenic relationships between Paracoccidioides loboi and other pathogenic fungi determined by immunofluorescenceMycopathol Mycol Appl1968362971064882637

- TabordaPRTabordaVAMcGinnisMRLacazia loboi gen. nov, comb. nov, the etiologic agent of lobomycosisJ Clin Microbiol19993762031203310325371

- HerrRATarchaEJTabordaPRTaylorJWAjelloLMendozaLPhylogenetic analysis of Lacazia loboi places this previously uncharacterized pathogen within the dimorphic OnygenalesJ Clin Microbiol200139130931411136789

- Lacaz CdaCParacoccidioides loboi (Fonseca Filho et Arêa Leão, 1940) Almeida et Lacaz, 1948–1949. Description of the fungus in LatinRev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo19963832292319163991

- FurtadoJSDe BritoTFreymullerEStructure and reproduction of Paracoccidioides loboiMycologia196759286294

- MendesEMichalanyNMendesNFComparison of the cell walls of Paracoccidioides loboi and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis by using polysaccharide-binding dyesInt J Tissue React19863229231

- LandmanGVelludoMALopesJAMendesECrossed-antigenicity between the etiologic agents of lobomycosis and paraccocidioidomycosis evidenced by an immunoenzymatic method (PAP)Allergol Immunopathol (Madr)19881642152183067565

- PucciaRTravassosLR43-kilodalton glycoprotein from Paracoccidioides brasiliensis: immunochemical reactions with sera from patients with paracoccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, or Jorge Lobo’s diseaseJ Clin Microbiol1991298161016151722220

- VidalMSPalaciosSAde MeloNTLacaz CdaSReactivity of anti-gp43 antibodies from Paracoccidioides brasiliensis antiserum with extracts from cutaneous lesions of Lobo’s disease. Preliminary noteRev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo199739135379394534

- VilelaRRosaPSBeloneAFTaylorJWDiórioSMMendozaLMolecular phylogeny of animal pathogen Lacazia loboi inferred from rDNA and DNA coding sequencesMycol Res2009113Pt 885185719439181

- Nery-GuamaraesFInoculacoes em hamsters da blasto micose sul-americana (doenca de Lutz), da blastomicose queloideana (doenca de Lobo) e da blastomicose dos indios do Tapajos-Xingu [Inoculations in hamsters of South American blastomycosis (Lutz’s disease), keloid-like blastomycosis (Lobo’s disease) and blastomycosis from the Indians of Tapaj’os-Cingu]Hospital (Rio J)196466581593 Portuguese14202717

- SampaioMMDiasLBExperimental infection of Jorge Lôbo’s disease in the cheek-pouch of the golden hamsterRev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo19701221151205517815

- Cardoso de BritoAQuaresmaJASLacaziosis (Jorge Lobo’s disease): review and updateAn Bras Dermatol200782461474

- BorelliDLobomicosis experimentalDerm Venez196237282

- LeiteMCDoença de Jorge Lobo (estudo de uma autoinoculação). MonografiaBelémUFPA199334

- Rodríguez-ToroGLobomycosisInt J Dermatol19933253243328505156

- Campo-AasenIBlastomicosis queloidiana o enfermedad de Jorge Lobo en VenezuelaDerm Venez19581215240

- PecherSACroceJFerriRGStudy of humoral and cellular immunity in lobomycosisAllergol Immunopathol (Madr)197976439444539528

- Vilani-MorenoFRBelone AdeFLaraVSVenturiniJLaurisJRSoaresCTDetection of cytokines and nitric oxide synthase in skin lesions of Jorge Lobo’s disease patientsMed Mycol201149664364821208026

- QuaresmaJAde OliveiraECardoso de BritoAIs TGF-beta important for the evolution of subcutaneuos chronic mycoses?Med Hypotheses20087061182118518068906

- XavierMBLibonatiRMUngerDMacrophage and TGF-beta immunohistochemical expression in Jorge Lobo’s diseaseHum Pathol200839226927417959227

- SmeltzRBChenJShevachEMTransforming growth factor-beta1 enhances the interferon-gamma-dependent, interleukin-12-independent pathway of T helper 1 cell differentiationImmunology2005114448449215804285

- QuaresmaJALimaLWFuziiHTLibonatiRMPagliariCDuarteMIImmunohistochemical evaluation of macrophage activity and its relationship with apoptotic cell death in the polar forms of leprosyMicrob Pathog201049413514020510345

- GellerPGellerMCytokines and immune regulationAn Acad Nac Med199715797102

- PecherSAFuchsJCellular immunity in lobomycosis (keloidal blastomycosis)Allergol Immunopathol (Madr)19881664134153242380

- Vilani-MorenoFRMozerEde SeneAMIn vitro and in situ activation of the complement system by the fungus Lacazia loboiRev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo20074929710117505668

- QuaresmaJAUngerDPagliariCSottoMNDuarteMIde BritoACImmunohistochemical study of Langerhans cells in cutaneous lesions of the Jorge Lobo’s diseaseActa Trop20101141596220044969

- Goihman-YahrMCabello de BritoIBastardo de AlbornozMCFunctions of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and individuality of Jorge Lobo’s disease: absence of the specific leukocyte digestive defect against Paracoccidioides brasiliensisMycoses198932126036082622474

- Vilani-MorenoFRSilvaLMOpromollaDVEvaluation of the phagocytic activity of peripheral blood monocytes of patients with Jorge Lobo’s diseaseRev Soc Bras Med Trop200437216516815094903

- Vilani-MorenoFRLaurisJROpromollaDVCytokine quantification in the supernatant of mononuclear cell cultures and in blood serum from patients with Jorge Lobo’s diseaseMycopathologia20041581172415487315

- TabordaVBTabordaPRMcGinnisMRConstitutive melanin in the cell wall of the etiologic agent of Lobo’s diseaseRev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo199941191210436664

- Vilani-MorenoFROpromollaDVDeterminação da viabilidade do Paracoccidioides loboi em biópsias de pacientes portadores de doença de Jorge LoboAnn Bras Dermatol (Rio de Janeiro)1997725433437

- StengerSMazzaccaroRJUyemuraKDifferential effects of cytolytic T cell subsets on intracellular infectionScience19972765319168416879180075

- OchoaMTStengerSSielingPAT-cell release of granulysin contributes to host defense in leprosyNat Med20017217417911175847

- LevitzSMDupontMPSmailEHDirect activity of human T lymphocytes and natural killer cells against Cryptococcus neoformansInfect Immun19946211942028262627

- CamargoZPBaruzziRGMaedaSMFlorianoMCAntigenic relationship between Loboa loboi and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis as shown by serological methodsMed Mycol199836641341710206752

- MendozaLBeloneAFVilelaRUse of sera from humans and dolphins with lacaziosis and sera from experimentally infected mice for Western Blot analyses of Lacazia loboi antigensClin Vaccine Immunol200815116416717959822

- SilvaDEstudo experimental da micose de LoboAn Bras Dermatol1994698891

- AzulayRDCarneiroJADa GraçaMCunhaSReisLTKeloidal blastomycosis (Lobo’s disease) with lymphatic involvement: a case reportInt J Dermatol19761514042942708

- RosaPSSoaresCTBelone AdeFAccidental Jorge Lobo’s disease in a worker dealing with Lacazia loboi infected mice: a case reportJ Med Case Rep200936719220901

- BorelliDLa Reservarea de al Lobomicosis Comentarios a un Trabajo del Dr. Carlos Peña sobre dos casos Colombianos [The reservoir area of lobomycosis. Comments on the work of Dr Carlos Peña on 2 Colombian cases]Mycopathol Mycol Appl196928372145149 Spanish5787929

- GuimaraesFNMacedoDGContribuição ao estudo das blastomicoses na Amazônia (blastomicose queloidiana e blastomicose sul-americana) [Blastomycosis in the Amazon Valley (keloidian and South American)]Hospital (Rio J)1950382223253 Portuguese15436089

- MoraesMAPOliveiraWRNovos casos da micose de Jorge Lobo encontrados em Manaus, Amazonas (Brasil)Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo19624403406

- NazaréIPMicose de LoboBelémGrafisa1976

- MigakiGValerioMGIrvineBGarnerFMLobo’s disease in an atlantic bottle-nosed dolphinJ Am Vet Med Assoc197115955785825106378

- BossartGDSuspected acquired immunodeficiency in an Atlantic bottlenosed dolphin with chronic-active hepatitis and lobomycosisJ Am Vet Med Assoc198418511141314146511606

- RotsteinDSBurdettLGMcLellanWLobomycosis in offshore bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus), North CarolinaEmerg Infect Dis200915458859019331739

- Paniz-MondolfiAESander-HoffmannLLobomycosis in inshore and estuarine dolphinsEmerg Infect Dis200915467267319331770

- KiszkaJVan BressemMFPusineriCLobomycosis-like disease and other skin conditions in Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins Tursiops aduncus from the Indian OceanDis Aquat Organ200984215115719476285

- CaldwellDKCaldwellMCWoodardJCAjelloLKaplanWMcClureHMLobomycosis as a disease of the Atlantic bottle-nosed dolphin (Tursiops truncatus Montagu, 1821)Am J Trop Med Hyg19752411051141111350

- ReifJSSchaeferAMBossartGDLobomycosis: risk of zoonotic transmission from dolphins to humansVector Borne Zoonotic Dis2013131068969323919604

- Daura-JorgeFGSimões-LopesPCLobomycosis-like disease in wild bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus of Laguna, southern Brazil: monitoring of a progressive caseDis Aquat Organ201193216317021381522

- Van BressemMFSantosMCOshimaJESkin diseases in Guiana dolphins (Sotalia guianensis) from the Paranaguá estuary, Brazil: a possible indicator of a compromised marine environmentMar Environ Res2009672636819101029

- Rodriguez-ToroGEnfermedad de Jorge Lobo o blastomicosis queloidiana. Nuevos aspectos de la entidad en ColombiaRev Bioméd (Bogota)19899133146

- Rodríguez-ToroGTellezNLobomycosis in Colombian Amer Indian patientsMycopathologia19921201591480207

- ReifJSPeden-AdamsMMRomanoTARiceCDFairPABossartGDImmune dysfunction in Atlantic bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) with lobomycosisMed Mycol200947212513518608890

- BermudezLVan BressemMFReyes-JaimesOSayeghAJPaniz-MondolfiAELobomycosis in man and lobomycosis-like disease in bottlenose dolphin, VenezuelaEmerg Infect Dis20091581301130319751598

- Paniz MondolfiALobomicosis: una aproximación después de 70 añosDermatol Venez200341137

- Paniz-MondolfiATalhariCSander HoffmannLLobomycosis: an emerging disease in humans and delphinidaeMycoses201255429830922429689

- Paniz-MondolfiAEReyes JaimesODávila JonesLLobomycosis in VenezuelaInt J Dermatol200746218018517269972

- RosalesTReyes JaimesOKeloidal and verrucous lesions in an Amerindian patientClin Exp Dermatol2010354e205e20620518918

- PradinaudREntre le Yucatan, la Floride et la Guyane Française, la lomycose exite-ti-elle aux Antilles? [Between Yucatan, Florida and French Guiana does lobomycosis exist in the Antilles?]Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales1984773392400 French6488429

- PradinaudRGrosshansEBassetMUn nouveau cas de maladie de Jorge Lobo en Guyane Française. [A new case of Jorge Lobo disease in French Guyana]Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr1969766837839 French5384220

- PradinaudRJolyFBassetMBassetAGrosshansELes chromomycoses et la maladie de Jorge Lobo en Guyane Française. [Chromomycosis and Jorge Lobo disease in French Guiana]Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales196962610541063 French5409181

- Garzón AldásEHerrera VicuñaVLobomicosis: una serie de 5 casosPiel2013285260263

- RivasOREnfermedad de Jorge Lobo: primer caso diagnosticado en el PeruArch Peruanos Pat Clin1972266386

- TalhariSCuba CaparoAGanterBEnfermedad de Jorge Lobo. Segundo caso peruano [Jorge Lobo’s disease. Second Peruvian case]Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am1985133201204 Spanish3906310

- BustamanteBSeasCSalomonMBravoFLobomycosis successfully treated with posaconazoleAm J Trop Med Hyg20138861207120823546805

- RecacoecheaMVargasJExperiencia con el ketoconazole en el primer caso de lobomicosis en BoliviaBol Inf CENETROP198282326

- HerreraJMParacoccidioides brasiliense: estudio del primer caso observado en Panama de blastomicosis sudamericana en su forma cutanea queloideana o enfermedad de Lobo, y propuesta de una variante tecnica para la impregnacion argentica del parasitoArch Med Panameños19554209201913303866

- TapiaATorres-CalcindoAArosemenaRKeloidal blastomycosis (Lobo’s disease) in PanamaInt J Dermatol1978177572574689802

- FonsecaJJLobomycosisInt J Surg Pathol2007151626317172499

- BurnsRARoyJSWoodsCPadhyeAAWarnockDWReport of the first human case of lobomycosis in the United StatesJ Clin Microbiol20003831283128510699043

- ElsayedSKuhnSMBarberDChurchDLAdamsSKasperRHuman case of lobomycosisEmerg Infect Dis200410471571815200867

- Saint-BlancardPMaccariFLe GuyadecTLanternierGLe VagueresseRLa lobomycose: une mycose rarement observée en France métropilitaine. [Lobomycosis: a mycosis seldom observed in metropolitan France]Ann Pathol2000203241244 French10891722

- SymmersWSA possible case of Lôbo’s disease acquired in Europe from a bottle-nosed dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales1983765 Pt 27777846231133

- FischerMChrusciak TalhariAReinelDTalhariSLobomykose Erfolgreiche Therapie mit Clofazimin und Itrakonazol bei einem 46-jährigen Patienten nach 32-jähriger Krankheitsdauer. [Sucessful treatment with clofazimine and itraconazole in a 46 year old patient after 32 years duration of disease]Hautarzt20025310677681 German12297950

- PapadavidEDalamagaMKapniariILobomycosis: A case from Southeastern Europe and review of the literatureJ Dermatol Case Rep201263656923091581

- BaruzziRGCastroRMD’AndrettaCJrCarvalhalSRamosOLPontesPLOccurrence of Lobo’s blastomycosis among “Caiabi,” Brazilian IndiansInt J Dermatol197312295994697345

- MachadoPASilveiraDFPiraip, a falsa lepra dos CaiabisRev Bras Leprol19663460

- BaruzziRGMarcopitoLFVicenteLSMichalanyNSJorge Lobo’s disease (keloidal blastomycosis) and tinea imbricata in Indians from the Xingu National Park, Central BrazilTrop Doct198212113157071925

- BaruzziRGMarcopitoLFDoença de Jorge LoboVeronesiRFocacciaRTratado de InfectologiaSão PauloAtheneu199611161119

- BaruzziRGd’AndrettaCJrCarvalhalSRamosOLPontesPLOcorrência de blastomicose queloideana entre índios Caiabí. [Occurrence of keloidal blastomycosis among Caiabi Indians]Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo196793135142 Portuguese5604165

- BaruzziRGLacaz CdaSde SouzaFAHistória natural da doença de Jorge Lobo. Ocorrência entre os índios Caiabí (Brasil Central). [Natural history of Jorge Lobo’s disease. Occurrence among the Caiabi Indians (Central Brazil)]Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo1979216303338 Portuguese550287

- BaruzziRGMarcopitoLFMichalanyNSLivianuJPintoNREarly diagnosis and prompt treatment by surgery in Jorge Lobo’s disease (keloidal blastomycosis)Mycopathologia198174151547242649

- MachadoPARegressão espontânea de lesões maculosas na blastomicose de Jorge LoboActa Amaz197224750

- RodríguezGNuevos casos colombianos de lobomicosisBiomedica1994144239241

- WiersemaJPNiemelPLLobo’s disease in Surinam patientsTrop Geogr Med1965172891115853472

- De VriesGALaarmanJJA case of Lobo’s disease in the dolphin Sotalia guianensisAquat Mamm197312633

- Al-DarajiWIHusainERobsonALobomycosis in African patientsBr J Dermatol2008159123423618460023

- NortonSADolphin-to-human transmission of lobomycosis?J Am Acad Dermatol200655472372417010761

- HauboldEMCooperCRJrWenJWMcGinnisMRCowanDFComparative morphology of Lacazia loboi (syn. Loboa loboi) in dolphins and humansMed Mycol200038191410746221

- EsperónFGarcía-PárragaDBellièreENSánchez-VizcaínoJMMolecular diagnosis of lobomycosis-like disease in a bottlenose dolphin in captivityMed Mycol201250110610921838615

- WoodsWJBelone AdeFCarneiroLBRosaPSTen years experience with Jorge Lobo’s disease in the state of Acre, Amazon region, BrazilRev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo201052527327821049233

- VilelaRMendozaLRosaPSMolecular model for studying the uncultivated fungal pathogen Lacazia loboiJ Clin Microbiol20054383657366116081893

- AzulayRDCarneiro JdeAde AndradeLCMicose de Jorge Lobo. Contribuição ao seu estudo experimental. Inoculações no homem e animais de laboratório e investigação imunológica. [Jorge Lobo blastomycosis. Etiology, experimental inoculation, immunology and pathology of the disease]An Bras Dermatol19704514766 Portuguese5507908

- OpromollaDVBeloneAFTabordaPRRosaPSLymph node involvement in Jorge Lobo’s disease: report of two casesInt J Dermatol2003421293894114636186

- NogueiraLMendesLRodriguesCASantosMTalhariSTalhariCLobomycosis and squamous cell carcinomaAn Bras Dermatol201388229329523739701

- SilvaDMicose de LoboRev Soc Bras Med Trop197268598

- SilvaDBritoAFormas clínicas não usuais da micose de LoboAn Bras Dermatol199469133136

- MachadoPAPolimorfismo das lesões dermatológicas na blastomicose de Jorge Lobo entre os índios CaiabiActa Amaz197229397

- MirandaMFSilvaAJVinyl adhesive tape also effective for direct microscopy diagnosis of chromomycosis, lobomycosis, and paracoccidioidomycosisDiagn Microbiol Infect Dis2005521394315878441

- MirandaMFCostaVSBittencourt MdeJBritoACEliminação transepidérmica de parasitas na doença de Jorge Lobo [Transepidermal elimination of parasites in Jorge Lobo’s disease]An Bras Dermatol20108513943 Portuguese20464085

- TalhariCChrusciak-TalhariAde SouzaJVAraújoJRTalhariSExfoliative cytology as a rapid diagnostic tool for lobomycosisMycoses200952218718918705665

- Ramos-E-SilvaMAguiar-Santos-VilelaFCardoso-de-BritoACoelho-CarneiroSLobomycosis. Literature review and future perspectivesActas Dermosifiliogr2009100Suppl 19210020096202

- de AndradeLMAzulayRDCarneiroJMicose de Jorge Lobo.(Estudo histopatológico). [Jorge Lobo mycosis(histopathological study)]Hospital (Rio J)196873411731184 Portuguese4899938

- Vilani-MorenoFRBeloneAFSoaresCTOpromollaDVImmunohistochemical characterization of the cellular infiltrate in Jorge Lobo’s diseaseRev Iberoam Micol2005221444915813683

- Dudok van HeelWHSuccessful treatment in a case of lobomycosis (Lobo’s Disease) in Tursiops truncatus (Mont) at Dolfinarium, HarderwijkAquat Mamm19775815

- LawrenceDNAjelloLLobomycosis in western Brazil: report of a clinical trial with ketoconazoleAm J Trop Med Hyg19863511621663946734

- CucéLCWroclawskiELSampaioSATreatment of paracoccidioidomycosis, candidiasis, chromomycosis, lobomycosis, and mycetoma with ketoconazoleInt J Dermatol19801974054086252105

- LondoñoFBlastomicosis queloidiana. A propósito de un caso tratado con anfotericina BMed Cutan Ibero Lat Am19682521524

- ReyesOGoihmanMGoldsteinCBlastomicosis queloidiana o enfermedad de Jorge Lobo. Comunicación previa sobre un caso observadoDerm Venez19602245255

- SilverieRRavissePVilarJPMoulinsCBlastomycosis chéloidienne ou maladie du Jorge Lobo en Guyane française. [Keloid blastomycosis or Jorge Lobo disease in French Guiana]Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales1963562935 French13992935

- CarneiroFPMaiaLBMoraesMALobomycosis: diagnosis and management of relapsed and multifocal lesionsDiagn Microbiol Infect Dis2009651626419679237

- BaruzziRGAzevedoRADoença de Jorge LoboMeiraDAClínica de doenças tropicais e infecciosasRio de JaneiroInterlivros1991299306

- SilvaDTraitement de la maladie de Jorge Lobo par la clofazimine (B663). [Treatment of Lobo’s disease with clofazimine (B 663)]Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales1978716409412 French755535

- TalhariSCunhaMGBarrosMLGadelhaADEnfermedad de Jorge Lobo: Estudio de 22 casos. [Jorge Lobo disease. Study of 22 new cases]Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am1981928796 Spanish7026930