Abstract

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) may occur in association with a variety of neurological diseases, and so may be encountered in the setting of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, extrapyramidal and cerebellar disorders, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, and brain tumors. The psychological consequences and the impact on social interactions may be substantial. Although it is most commonly misidentified as a mood disorder, particularly depression or a bipolar disorder, there are characteristic features that can be recognized clinically or assessed by validated scales, resulting in accurate identification of PBA, and thus permitting proper management and treatment. Mechanistically, PBA is a disinhibition syndrome in which pathways involving serotonin and glutamate are disrupted. This knowledge has permitted effective treatment for many years with antidepressants, particularly tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. A recent therapeutic breakthrough occurred with the approval by the Food and Drug Administration of a dextromethorphan/quinidine combination as being safe and effective for treatment of PBA. Side effect profiles and contraindications differ for the various treatment options, and the clinician must be familiar with these when choosing the best therapy for an individual, particularly elderly patients and those with multiple comorbidities and concomitant medications.

Introduction

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) is characterized by uncontrolled crying or laughing which may be disproportionate or inappropriate to the social context. Thus, there is a disparity between the patient’s emotional expression and his or her emotional experience. Terminology has been varied and somewhat confusing, including involuntary emotional expression disorder, emotional lability, emotional dysregulation, pathological laughter and crying, emotional dysregulation, emotional incontinence, and emotionalism. PBA may be encountered in the setting of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), extrapyramidal and cerebellar disorders (Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy), multiple sclerosis (MS), traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, stroke, and brain tumors.Citation1,Citation2 Its impact is substantial, resulting in embarrassment for the patient, family, and caregivers with subsequent restriction of social interactions and a lower quality life. This contributes to additional disease burden in patients already impacted by a serious neurological disorder.Citation3 Tateno et al noted that when compared to patients without PBA, those with PBA had a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms and poorer social functioning.Citation4 PBA has been associated with a higher prevalence of diagnosable psychiatric disorders,Citation5 and about 30%–35% of patients with PBA are depressed.Citation6,Citation7 PBA has also been noted to interfere with rehabilitation; a report of patients with locked-in syndrome and PBA revealed that PBA interfered with evaluation and treatment of swallowing dysfunction, the effective use of any remaining motor ability, and with attempted communication by the patient.Citation8 Thus, recognition of this syndrome and familiarity with its treatment are important aspects of management of patients with a variety of neurological disorders, and provide the clinician with an opportunity to have a positive impact on these patients’ lives.

Epidemiology

The disorder occurs in association with a variety of brain disorders ().Citation9 The range of estimates of prevalence in various neurological disorders is high, ranging from 5% to well over 50%, depending on diagnostic criteria, methodologies, and patient populations studied.Citation2,Citation10–Citation14 In particular, the differentiation between emotional responses that are concordant with mood but exaggerated, and those that are discordant with mood, has led to substantial differences in published prevalence rates. A recent novel attempt to estimate the prevalence of PBA in the USA across six neurological disorders utilized an online survey of patients with ALS, MS, Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and traumatic brain injury.Citation15 Depending upon the scoring criteria used for the online instruments, prevalence rates ranged from 9.4%–37.5%, resulting in an estimated 1.8–7.1 million affected individuals in the USA. Even if the lower estimate is accepted as being the most accurate, this means that PBA is a significant national health issue in the USA, occurring in greater numbers of individuals than those affected by Parkinson’s disease, MS, or ALS.

Table 1 Neurological disorders most commonly associated with pseudobulbar affect

Pathophysiology

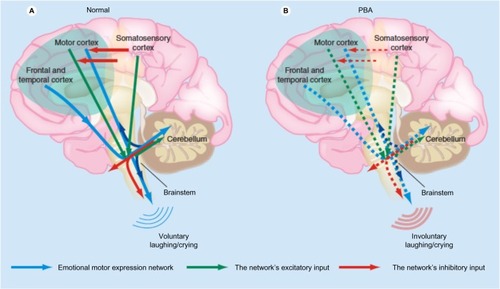

The underlying mechanism in PBA appears to be a lack of voluntary control, also termed disinhibition, but the pathways are complex and are as yet incompletely understood. Detailed reviews of the widespread anatomical and neurophysiological abnormalities found by neuroimaging and neurophysiological studies in patients with PBA have been published.Citation1,Citation14 The cerebellum appears to play a far larger role in PBA than was hypothesized a few years ago. There are pathways from the cortex to pons to cerebellum that appear to control not only motor, but also cognitive and affective function. In support of this, patients with cerebellar lesions may demonstrate abnormalities of affect and may show emotional lability,Citation16 and patients with multiple system atrophy – cerebellar type have a high frequency of PBA.Citation17 One hypothesis is that the cerebellum plays a key role in modulating emotional responses so as to keep them appropriate to the social situation and to the patient’s mood based on input from the cerebral cortex. Disruption of corticopontine–cerebellar circuits results in impairment of this cerebellar modulation, causing PBA.Citation2,Citation14 There appears to be both sensory and motor input. A theory has been proposed in which the motor control of emotions is modulated by the cerebellum, which acts as a “gate control.” There is direct input from the motor cortex and from the frontal and temporal cortices through the brainstem which is modulated by the cerebellum. The motor input is in turn modulated by inhibitory input from the somatosensory cortex. Reduction of the inhibitory input results in disinhibition of the cerebellum, resulting in socially inappropriate or situationally disproportionate emotional expression, which is manifested as PBA ().Citation14,Citation18 The manner in which specific cerebellar circuitry is involved in this process is the subject of ongoing investigations.Citation14,Citation19,Citation20 The primary neurotransmitters believed to be involved in PBA are serotonin and glutamate. The role of serotonin in corticolimbic or cerebellar pathways may account for its impact on PBA. Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter whose receptors are widely distributed within the brain. Thus, modulation of glutamatergic transmission can have widespread effects.Citation14

Figure 1 Proposed pathophysiology of pseudobulbar affect. (A) Input from the motor, frontal, and temporal cortices to the brainstem is modulated by input from the cerebellum. Inhibitory input from the somatosensory cortex modulates the motor input. (B) Reduced inhibitory input (broken red arrows in the cortex) results in disinhibition, giving rise to pseudobulbar affect.

Abbreviation: PBA pseudobulbar affect.

Clinical presentation

Clinicians are familiar with the manner in which the behavior of these patients is conveyed to them by those close to the patient. The episodes of emotion are perceived by others as being unprovoked and disconnected from the situational context, or as being out of proportion to the mood and feelings of the patient. Crying is often described as occurring in situations that are sad or otherwise emotionally touching, but which would not have produced such a striking emotional response from the patient in the past. Examples might include a sad television show, the death of a distant relative, or a show of affection by a child or grandchild. Uncontrolled laughing may occur in situations that are only mildly amusing and may have produced a chuckle under normal circumstances.Citation21 The degree of the emotional response by the patient is often striking, with the crying or laughter persisting for a considerable period of time, and unable to be suppressed by the patient. In addition, laughing and crying by the patient may occur in situations that are not perceived by others as being sad or being funny. Even a discussion of PBA and those factors triggering it may be enough to result in a clear demonstration of an exaggerated emotional response.Citation21,Citation22 Crying appears to be a more common manifestation of PBA than laughter.Citation6,Citation13

Differential diagnosis

The clinician may easily mistake the exaggerated and disproportionate crying seen in PBA for depression. This should not be surprising to any clinician, as the neurological disorders associated with PBA are life-changing conditions which often have a substantial emotional impact. The overlap between pathological crying and depression is complex, and the two are not entirely independent of one another in ALS.Citation7 Similarly, patients with movement disorders who demonstrated PBA were found to have higher depression symptom scores and lower scores of emotional wellbeing than those without PBA,Citation13 and various degrees of overlap between PBA and mood disorders have been identified in patients with stroke.Citation21,Citation23 Duration can be useful in distinguishing PBA from depression. Depression is of longer duration than the episodes of pathological crying characteristic of PBA – commonly lasting weeks to months in contrast to the very brief duration of PBA episodes. Both the exaggerated emotional response and the discordance between mood and emotional display are the other characteristics of PBA that are not expected with depression. PBA patients often lack the neurovegetative features of depression such as sleep disturbances and loss of appetite. There are published criteria to help differentiate PBA from depression.Citation9,Citation21 It is also important to distinguish PBA from bipolar disorders.Citation24 Overall, the use of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, criteria for the diagnosis of mood disorders, including the performance of semistructured interviews, can minimize confusion with PBA. Other neurological and psychiatric disorders within the differential diagnosis can usually be distinguished in a straightforward manner by clinicians, including various forms of epilepsy, tics, and dystonia. Drug-induced effects should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Diagnosis

PBA is most often judged to be present by the clinician in an informal manner, as part of his or her neurological evaluation. Criteria have been established in an attempt to define the syndrome more objectively. In 1969, Poeck defined four criteria for PBA ().Citation25 Poeck’s criteria did not identify relationships with specific precipitants, although some subsequent publications have done so. These have clarified that the emotional response is not necessarily inconsistent with mood – although it may be – but the degree of the emotional response is disproportionate. A more recent set of diagnostic criteria has been proposed which emphasizes that PBA is a change from the patient’s previous emotional responses, and also provides other specific characteristics ().Citation9

Table 2 Diagnostic criteria for pseudobulbar affect

PBA may be more objectively measured by published scales. The Center for Neurologic Study – Lability Scale (CNS-LS) is a seven-item self-administered questionnaire that asks about the control of laughter and crying, and has been validated in patients with ALS and MS.Citation7,Citation26 Scores range from one to five for each question, resulting in a total score of seven (no excess emotional lability) to 35 (severe excess emotional lability). A cutoff of 13 accurately predicted neurologists’ clinical diagnosis in 82% of ALS patients. Such a cutoff for patients with MS was less accurate, predicting the neurologist’s diagnosis 78% of the time in cases with low specificity, leading to a high number of false positives. Raising the cutoff to 17 for patients with MS improved the specificity without meaningfully affecting the sensitivity. The Pathological Laughter and Crying Scale (PLACS) is an interviewer-administered instrument consisting of 18 questions inquiring about sudden episodes of laughter and crying.Citation27 It has been validated in patients with acute stroke, and has shown excellent interrater and test–retest reliability. Scores for each question range from zero (normal) to three (excessive emotional lability). A cutoff score of 13 yielded high sensitivity and specificity of 0.96, and resulted in a positive predictive value of 0.83. Both of these instruments have been used in studies of treatment of PBA, as described below.

In practice, PBA is likely underdiagnosed, perhaps because of confusion with depression and other neurologic and psychiatric disorders. Although the merits of online surveys can certainly be debated, it is striking that one such survey found that only 41% of those who were identified as having PBA by the survey and who discussed their emotional responses with their physician were diagnosed by that physician as having PBA, and only 52% of those received a prescription for treatment.Citation15

Treatment

General principles

The goal of treatment of PBA is to diminish the severity and frequency of episodes. The targets of treatment are primarily norepinephrine, serotonin, or glutamate, using tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reductase inhibitors (SSRIs), and, most recently, the cough suppressant dextromethorphan. Historically, dopaminergic medications such as levodopa and amantadine have been used as well, but with lower response rates.Citation28 The serotonergic action of SSRIs and TCAs appears to be the most significant therapeutic mechanism in treatment of PBA, via an increase in availability of serotonin at the synapses in corticolimbic and cerebellar pathways. SSRIs have a relatively narrow mechanism of action, directed toward enhancing serotonergic function, whereas TCAs alter a broader range of neurotransmitter functions.

In contrast to SSRIs and TCAs, dextromethorphan inhibits glutamatergic neurotransmission via actions at a variety of locations including N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors and σ-1 receptors.Citation29 In administering dextromethorphan as monotherapy, there is rapid and extensive conversion by the liver to a related compound which is unable to cross the blood–brain barrier. This results in extremely low plasma concentrations of dextromethorphan even with the administration of very high oral doses. Blockade of hepatic metabolism can be accomplished by the concurrent administration of the cardiac antiarrhythmic drug quinidine sulfate,Citation24 leading to higher and sustained plasma concentrations of dextromethorphan at a fraction of the dose required if quinidine sulfate was not used.

Until recently, all treatments have, of necessity, been off-label. Four major uncontrolled trials of antidepressants in PBA all used SSRIs and reported favorable outcomes (), although the severity scales used as outcome measures were unvalidated.Citation6,Citation24,Citation30,Citation31 Pioro recently published a review of the treatment of PBA in which he identified 22 published case reports or therapeutic trials of at least five patients from 1980 through to 2010.Citation24 He identified ten randomized, double-blind studies with placebo controls. Six of them used some form of a severity scale and had 20 or more patients ().Citation27,Citation33–Citation37 The others used clinical judgment and/or patient-reported episode rates and had fewer than 20 patients. The response to active treatment either with an antidepressant or dextromethorphan/quinidine was greater in all placebo-controlled trials than the response to placebo. The efficacy of antidepressants appears to be unrelated to the treatment of depression, based upon several pieces of evidence: 1) the onset of action may occur within a few days, which is faster than expected for depression; 2) doses are lower than those usually used to treat depression; and 3) most patients with PBA are not depressed.Citation6,Citation7

Table 3 Uncontrolled trials of selective serotonin reductase inhibitors in pseudobulbar affect

Table 4 Placebo-controlled trials of medications in pseudobulbar affect

In October 2010, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Nuedexta® (Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA) for the treatment of PBA, making this the first FDA-approved drug for this indication. This compound contains dextromethorphan 20 mg and quinidine 10 mg, thus taking advantage of the blockade exerted by quinidine on the first-pass hepatic metabolism of dextromethorphan. Approval was granted on the basis of a large randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 326 patients with MS or ALS who had clinically significant PBA (). The treated group of patients demonstrated only about half as many laughing and crying episodes as were recorded in the placebo-treated cohort.Citation35

Specific recommendations

When determining which treatment to select, the clinician must consider tolerance and the potential for adverse effects as major factors. TCAs, with their broad effects on monoaminergic, cholinergic, and histaminergic neurotransmission, may produce a wide range of side effects including dry mouth, constipation, orthostatic hypotension, confusion, sedation, and potential cardiotoxicity. The elderly often tolerate TCAs particularly poorly. However, TCAs may facilitate sleep if given as a nighttime dose. Also, their anticholinergic properties make them useful for control of sialorrhea in patients such as those with bulbar ALS in whom this may be particularly troublesome. The actions of SSRIs, being largely limited to the enhancement of serotonergic function, generally have a much more limited side effect profile, resulting in a much lower rate of discontinuation.Citation24,Citation38 Of course both SSRIs and TCAs can be used to treat concomitant depression, although the physician should be attuned to the higher doses and longer time frames usually needed for the treatment of depression as compared to PBA.

Dosing ranges are broad, but the average dose of SSRIs in clinical trials for the treatment of PBA was 20 mg/day for fluoxetine and citalopram and 50 mg/day for sertraline.Citation14 Not unexpectedly, these are at the low end of the range usually used for treatment of depression. The commonly used TCAs are nortriptyline and amitriptyline, usually at dosages from 20–100 mg/day,Citation27,Citation39 and usually given as a single bedtime dose to minimize adverse effects and maximize tolerability.

There is more limited clinical experience with dextromethorphan/quinidine because of the relatively recent FDA approval. However, the most common side effects are dizziness, diarrhea, falls, headache, nausea, fatigue, nasopharyngitis, constipation, and dysphagia. At the dose contained in the approved compound, quinidine did not demonstrate adverse cardiac effects.Citation24,Citation37 The American Academy of Neurology published guidelines in 2009 which recommended that dextromethorphan/quinidine “should be considered for treatment of PBA in patients with ALS, if approved by the FDA and if side effects are acceptable.”Citation12 Updated guidelines have yet to be issued. The FDA-approved dosing is one capsule daily for 7 days, followed by an increase to one capsule every 12 hours.

Conclusion

PBA can impact quality of life and disease burden in patients with many commonly encountered neurological disorders, independent of disturbances of mood. Although the mechanisms are not fully understood, serotonergic and glutamatergic transmission appear to play major roles, and there are clear therapeutic benefits in treatment with SSRIs, TCAs, or with dextromethorphan/quinidine. By managing PBA with an appropriate pharmacologic approach, clinicians can have a meaningful impact on symptoms that are socially embarrassing and functionally limiting for these patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ParviziJArciniegasDBBernardiniGLDiagnosis and management of pathological laughter and cryingMayo Clin Proc200681111482148617120404

- ParviziJCoburnKLShillcuttSDCoffeyCELauterbachECMendezMFNeuroanatomy of pathological laughing and crying: a report of the American Neuropsychiatric Association Committee on ResearchJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci2009211758719359455

- ColamonicoJFormellaABradleyWPseudobulbar affect: burden of illness in the USAAdv Ther201229977579822941524

- TatenoAJorgeRERobinsonRGPathological laughing and crying following traumatic brain injuryJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci200416442643415616168

- CalvertTKnappPHouseAPsychological associations with emotionalism after strokeJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry19986569289299854975

- MüllerUMuraiTBauer-WittmundTvon CramonDYParoxetine versus citalopram treatment of pathological crying after brain injuryBrain Injury1999131080581110576464

- MooreSRGreshamLSBrombergMBKasarkisEJSmithRAA self report measure of affective labilityJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry199763189939221973

- SaccoSSaraMPistoiaFConsonMAlbertiniGCaroleiAManagement of pathologic laughter and crying in patients with locked-in syndrome: a report of 4 casesArch Phys Med Rehabil200889477577818374012

- CummingsJLArciniegasDBBrooksBRDefining and diagnosing involuntary emotional expression disorderCNS Spectr20061161716816786

- GallagherJPPathologic laughter and crying in ALS: a search for their originActa Neurol Scand19898021141172816272

- McCullaghSMooreMGawelMFeinsteinAPathological laughing and crying in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an association with prefrontal cognitive dysfunctionJ Neurol Sci1999169124348

- MillerRGJacksonCEKasarskisEJPractice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: multidisciplinary care, symptom management, and cognitive/behavioral impairment (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of NeurologyNeurology200973151227123319822873

- StrowdRECartwrightMSOkunMSHaqISiddiquiMSPseudobulbar affect: prevalence and quality of life impact in movement disordersJ Neurol201025781382138720376475

- MillerAPrattHSchifferRBPseudobulbar affect: the spectrum of clinical presentations, etiologies and treatmentsExpert Rev Neurother20111171077108821539437

- WorkSSColamonicoJABradleyWGKayeREPseudobulbar affect: an under-recognized and under-treated neurological disorderAdv Ther201128758660121660634

- SchmahmannJDShermanJCThe cerebellar cognitive affective syndromeBrain1998121Pt 45615799577385

- ParviziJJosephJPressDZSchmahmannJDPathological laughter and crying in patients with multiple system atrophy-cerebellar typeMov Disord200722679880317290465

- HaimanGPrattHMillerABrain responses to verbal stimuli among multiple sclerosis patients with pseudobulbar affectJ Neurol Sci20082711–213714718504049

- HoltzmanTRajapaksaTMostofiAEdgleySADifferent responses of rat cerebellar Purkinje cells and Golgi cells evoked by widespread convergent sensory inputsJ Physiol2006574Pt 249150716709640

- BarmackNHYakhnitsaVFunctions of interneurons in mouse cerebellumJ Neurosci20082851140115218234892

- HouseADennisMMolyneuxAWarlowCHawtonKEmotionalism after strokeBMJ198929866799919942499390

- RosenHJCummingsJA real reason for patients with pseudobulbar affect to smileAnn Neurol2007612929617212357

- MorrisPLRobinsonGRaphaelBEmotional lability after strokeAust N Z J Psychiatry19932746016058135684

- PioroEPCurrent concepts in the pharmacotherapy of pseudobulbar affectDrugs20117191193120721711063

- PoeckKPathophysiology of emotional disorders associated with brain damageVinkenPJBruynGWHandbook of Clinical NeurologyAmsterdamNorth Holland Publishing19693343367

- SmithRABergJEPopeLECallahanJDWynnDThistedRAValidation of the CNS emotional lability scale for pseudobulbar affect (pathological laughing and crying) in multiple sclerosis patientsMult Scler200410667968515584494

- RobinsonRGParikhRMLipseyJRStarksteinSEPriceTRPathological laughing and crying following stroke: validation of a measurement scale and a double-blind treatment studyAm J Psychiatry199315022862938422080

- UdakaFYamaoSNagataHNakamuraSKameyamaMPathologic laughing and crying treated with levodopaArch Neurol19844110109510966477219

- WerlingLLKellerAFrankJGNuwayhidSJA comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorderExp Neurol2007207224825717689532

- SeligerGMHornsteinAFlaxJHerbertJSchroederKFluoxetine improves emotional incontinenceBrain Inj1992632672701581749

- SloanRLBrownKWPentlandBFluoxetine as a treatment for emotional lability after brain injuryBrain Inj1992643153191638265

- IannacconeSFerini-StrambiLPharmacologic treatment of emotional labilityClin Neuropharmacol19961965325358937793

- BrownKWSloanRLPentlandBFluoxetine as a treatment for post-stroke emotionalismActa Psychiatr Scand19989864554589879787

- BurnsARussellEStratton-PowellHTyrellPO’NeillPBaldwinRSertraline in stroke-associated lability of moodInt J Geriatr Psychiatry199914868168510489659

- Choi-KwonSHanSWKwonSUKangDWChoiJMKimJSFluoxetine treatment in poststroke depression, emotional incontinence, and anger proneness: a double-blind, placebo-controlled studyStroke200637115616116306470

- PanitchHSThistedRASmithRARandomized, controlled trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine for pseudobulbar affect in multiple sclerosisAnn Neurol200659578078716634036

- PioroEPBrooksBRCummingsJDextromethorphan plus ultra low-dose quinidine reduces pseudobulbar affectAnn Neurol201068569370220839238

- AndersonIMSelective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerabilityJ Affect Disord2000581193610760555

- SchifferRBHerndonRMRudickRATreatment of pathologic laughing and weeping with amitriptylineN Engl J Med198531223148014823887172