Abstract

Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) is a rare inflammatory disorder that has been recently classified as a polygenic autoinflammatory disorder. The former classification, based on the disease course, seems to be quite dated. Indeed, there is accumulating evidence that AOSD can be divided into two distinct phenotypes based on cytokine profile, clinical presentation, and outcome, ie, a “systemic” pattern and an “articular” pattern. The first part of this review deals with the treatments that are currently available for AOSD. We then present the different strategies based on the characteristics of the disease according to clinical presentation. To do so, we focus on the two subsets of the disease. Finally, we discuss the management of life-threatening complications of AOSD, along with the therapeutic options during pregnancy.

Introduction

Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) is a rare inflammatory disorder characterized by the classical triad of daily spiking fever, arthritis, and typical salmon-colored rash. It was first described in 1971 by Bywaters, who defined the disease on the basis of clinical and laboratory resemblance to juvenile Still’s disease.Citation1 Indeed, in 1897, George Frederic Still had described 22 children with what is now called systemic-onset idiopathic juvenile arthritis (JIA).Citation2,Citation3 Whether AOSD and systemic-onset JIA belong to the same continuum of disease is still debated, but the evidence strongly suggests that AOSD and systemic-onset JIA are the same disease.Citation4–Citation6

The epidemiology, diagnostic criteriaCitation7,Citation8 (), and classification of AOSD have been reviewed recently.Citation9,Citation10 The pathophysiology of AOSD remains obscure, and identification of an etiologic trigger is still lacking.

Table 1 Criteria for the diagnosis of adult-onset Still’s disease

Over the last decade, one striking event was the reclassification of AOSD as a polygenic autoinflammatory disorder.Citation11,Citation12 This has mainly been deduced from demonstration of the pivotal role of innate immune pathways, mostly those involved in the processing of two cytokines of the interleukin (IL)-1 family (namely, IL-1β and IL-18). Other cytokines, such as IL-6 and to a lesser extent tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), are also involved in the pathogenesis of AOSD. Data from genetic and immunologic studies, together with the dramatic effect of biologic treatments, have confirmed the major role of these cytokines. Recently, there has been accumulating evidence that AOSD can be divided into two distinct phenotypes based on cytokine profile, clinical presentation, and outcome.Citation10,Citation13–Citation15 These are discussed in this review.

The renewed comprehension of the disease, along with the availability of new cytokine inhibitors, has led to new therapeutic approaches. The general aim of this review is to discuss the optimal management of AOSD. The first part deals with the treatments that are currently available for AOSD. We then present the different strategies based on characteristics of the disease according to clinical presentation.

Available treatments

Given that the current information on treatment efficacy is obtained from small retrospective case series and not from prospective, double-blind, randomized trials, the treatment of AOSD remains empirical. In contrast, due to a higher prevalence, more data are available for systemic-onset JIA and will be discussed briefly. Recently, the management of AOSD has benefited from proofs of the efficacy of targeted biotherapies.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids

Regarding available data on AOSD, the risk/benefit ratio is not favorable with regard to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Indeed, more than 80% of AOSD patients did not achieve remission with NSAIDs and approximately 20% suffered adverse events.Citation16,Citation17 Nevertheless, temporary use of NSAIDs can be considered during diagnostic workup or for early relapse of the disease.Citation17

Corticosteroids remain the first-line treatment for AOSD, regardless of the clinical presentation. Nevertheless, studies of systemic-onset JIA are providing evidence that some biologics should be used earlier in the course of the disease (see section on IL-1 antagonists).Citation18–Citation21 In addition, new treatment plans for systemic-onset JIA have placed methotrexate, anakinra, and tocilizumab as possible first-line treatments.Citation22 Corticosteroids control about 60% of patients and show greater efficacy with regard to systemic symptoms than articular ones.Citation17,Citation23,Citation24 Steroid dependency occurs in approximately 45% of cases. and has been associated with splenomegaly, low glycosylated ferritin, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and young age at onset of AOSD.Citation16,Citation25 Thus, early addition of a steroid-sparing agent may be considered in patients who meet these criteria.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intravenous immunoglobulin

In the event of failure of corticosteroid treatment or steroid-dependence, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDS) can be considered.Citation16,Citation25 Some retrospective case series and case reports have reported the efficacy of several DMARDs, such as cyclosporine A, leflunomide, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine,Citation23,Citation26 D-penicillamine, and tacrolimus.Citation17,Citation27,Citation28 However, positive results remain exceptional and these agents cannot be recommended unless severe complications occur and other more specific drugs have failed.Citation27

In contrast, methotrexate has proved beneficial and remains the first-line steroid-sparing treatment in AOSD.Citation16,Citation17 As for systemic-onset JIA, targeted biologic therapies (such as anakinra or tocilizumab) are possible alternatives, which could be used for a steroid-sparing effect. Methotrexate can lead to complete remission in up to 70% of patients and corticosteroid weaning has also been reported in some cases.Citation29 Liver enzyme abnormalities do not contraindicate its prescription but require close biological monitoring.

Data concerning intravenous immunoglobulin are more controversial, with two randomized open-label trials showing some efficacy when used early in the course of AOSD,Citation30,Citation31 whereas retrospective data do not support the efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin in AOSD.Citation16,Citation25 Overall, intravenous immunoglobulin has only a suspensive effect but is well tolerated. Thus, it should be considered in the event of reactive hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (RHL; formerly known as macrophage activation syndrome),Citation32 in some life-threatening complications, or in case of AOSD flare-up occurring during pregnancy.Citation33,Citation34 The usual dosage is 2 g/kg body weight administered in 2–5 days.

Targeted biologic therapies

Although dramatic responses have been reported in systemic-onset JIA when given as first-line treatment, targeted biologic agents are actually reserved for refractory AOSD.Citation19,Citation21,Citation22,Citation35 Resistance to first-line corticosteroids and second-line DMARDs defines refractory AOSD, which mostly includes the polycyclic or chronic courses of the disease. Data concerning biologic agents used in AOSD are summarized in .

Table 2 Review of previous use of biologic agents for refractory adult-onset Still’s disease

Anti-TNF-α

Historically, anti-TNF therapy was the first biologic therapy that was used to treat refractory AOSD. The administration schemes were based on those used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. The three anti-TNF-α agents (ie, infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab) have been used to treat refractory AOSD but data on adalimumab are limited to a few cases.Citation36 Data from case reports, retrospective case series, and one prospective open-label prospective trial are available. Complete remissions have been observedCitation37–Citation41 but anti-TNF therapy was rather disappointing, mostly for systemic symptoms.Citation10,Citation42 Switching from one molecule to another had no additional effect.Citation16,Citation43 Moreover, two patients who were started on etanercept and adalimumab developed RHL that could be linked with initiation of the treatment.Citation44,Citation45 Overall, TNF-α blockers seem to be of interest only for the treatment of chronic polyarticular disease.Citation16,Citation17,Citation23,Citation25 In that case, based on our experience and on analysis of the literature, infliximab should be the preferred molecule because of better efficacy. However, no prospective evidence sustains this preferred option, and each case should be carefully evaluated by AOSD experts before therapeutic changes.

IL-1 antagonists

Three IL-1 antagonists are presently available, ie, a recombinant antagonist of the IL-1 receptor (IL-1Ra, anakinra), a human monoclonal antibody directed against IL-1β (canakinumab), and a soluble IL-1 trap fusion protein (rilonacept). Anakinra has been more frequently reported in the treatment of AOSD.Citation35,Citation46–Citation52

The efficacy of anakinra has been reported in retrospective case seriesCitation35,Citation46–Citation51 and in one prospective, randomized, open-label trial.Citation52 Anakinra is particularly efficient in the rapid relief of systemic symptoms. Its effect on articular symptoms is less frequently reported. In almost all cases, inflammatory markers reverted to normal within about 2 weeks and corticosteroids could be tapered and discontinued. However, the effect of anakinra was suspensive, and relapses occurred frequently as soon as the treatment was stopped. In some cases, progressive dose reduction has enabled the weaning of anakinra. In the event of an insufficient response to anakinra, rilonacept and canakinumab can be considered because they have longer half-lives and can be administered every week or every 8 weeks, respectively. Indeed, both agents have been reported to be efficient in AOSD.Citation53–Citation56

More data are available in the setting of systemic-onset JIA.Citation19,Citation20,Citation55–Citation58 Swart et al reviewed the literature and reported on 140 children with systemic-onset JIA treated with anakinra.Citation57 Systemic symptoms resolved in 98% of the patients who had such symptoms. Fatigue and well-being improved in 93% of cases. Arthritis improved in 66% of the cases within a longer time (few months).

Complete disease remission was mostly observed in patients with systemic symptoms, less arthritis, and a shorter duration of disease. Adverse events were most frequently pain and erythema at the injection site. More serious adverse events were rare (occurring in eight cases). Quartier et al confirmed the efficacy of anakinra in systemic-onset JIA by performing a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial.Citation58 The study included 24 patients with a systemic-onset JIA duration of more than 6 months and steroid dependency. After one month, anakinra had been effective in 8/12 patients (versus one in the placebo group) who reached the modified American College of Rheumatology Pediatric 30 score. At month 2, 9/10 patients in the placebo group who had been switched to anakinra were also responders. However, during the following open-label treatment period, a loss of response was observed over time and no patient achieved inactive disease.

Nigrovic et al reported on 46 patients who received anakinra as first-line treatment.Citation19 Rapid resolution of systemic symptoms was observed in more than 95% of cases, along with an additional preventive effect on refractory arthritis in almost 90% of the patients. Notably, 60% of the patients achieved inactive disease. Based on these results, Nigrovic postulated that there could be a “window of opportunity” for IL-1 blockade if given at the very beginning of the disease (ie, within 6 months after onset).Citation18 In Nigrovic’s model, systemic-onset JIA/AOSD would have a biphasic pattern. The first phase, being febrile and inflammatory, involves innate immunity, and evolves to an afebrile phase with chronic destructive arthritis involving adaptive immunity. This hypothesis has been somewhat reinforced by the results reported by Vastert et al in 2014.Citation20 Indeed, they reported on a prospective series of 20 patients who received anakinra as first-line therapy. Eighty-five percent of the patients showed an American College of Rheumatology Pediatric 90 score response or had inactive disease within 3 months. Overall, 75% of the patients treated with anakinra alone achieved inactive disease. Although it is difficult to evaluate to what extent children with new-onset systemic-onset JIA enrolled in that study would have underwent monocyclic course (ie disease that never relapses), these dramatic results clearly indicate that IL-1 blockade has an early place in the treatment strategy.

Tocilizumab

Tocilizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against the IL-6 receptor that has shown positive results in patients with refractory AOSD from several case series.Citation59–Citation62 Results from randomized placebo-controlled trials are available in systemic-onset JIA but not in AOSD.Citation63,Citation64 Generally, the patients responded rapidly and experienced a sustained clinical remission over time. Moreover, the effect of tocilizumab persisted for ≥6 months after its discontinuation. Tocilizumab seems to have a similar beneficial effect on the systemic and articular features of AOSD, has a marked corticosteroid-sparing effect, and has a good safety and tolerance profile.Citation59–Citation61,Citation63 Indeed, in a recent retrospective series, only two cases among 34 tocilizumab-treated patients with AOSD had to withdraw from treatment due to severe infections.Citation62 Other side effects were mild leukopenia or neutropenia, elevation of hepatic enzymes, hypercholesterolemia, and headache associated with tocilizumab infusion.

Optimal management of AOSD

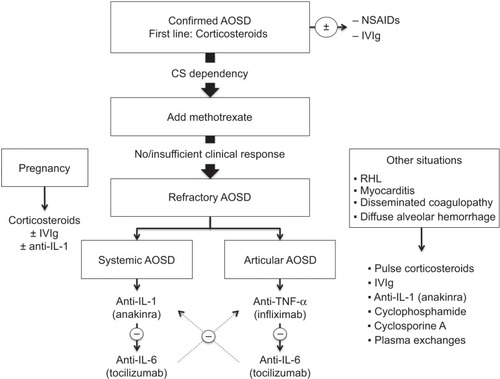

Since the management of AOSD varies widely depending on the various clinical presentations of the disease, the optimal management is discussed in the second part of this review. A management algorithm is provided in .

Figure 1 Management algorithm for adult-onset Still’s disease.

Nonrefractory AOSD

According to the abovementioned definition, nonrefractory AOSD corresponds to disease patterns that can be cured by using first-line corticosteroids ± methotrexate. This mostly includes the monocyclic and polycyclic courses of the disease, when corticosteroid dependency can be overcome with a first-line steroid-sparing agent. NSAIDs can be used during the diagnostic workup, in case of a monocyclic course of AOSD without major systemic or articular involvement or in case of isolated mild articular involvement. In such cases, the preferred NSAID is high-dose indomethacin (150–200 mg/day).Citation26,Citation65,Citation66

Corticosteroids should be started promptly once the diagnosis is confirmed. Usually, corticosteroid therapy starts at a dosage of 0.5–1 mg/kg/day, but an intravenous pulse of high-dose methylprednisolone can be used, particularly where there is severe visceral involvement.Citation67,Citation68 Higher dosages seem to be more efficient in controlling the disease, achieving remission earlier, and decreasing the number of relapses.Citation10 Fractionated daily intakes of corticosteroids have also provided interesting results in insufficiently controlled patients.Citation26,Citation69 The response to corticosteroids should be obtained within hours or days.Citation70 Usually, the tapering of corticosteroids can start after 4–6 weeks, when symptoms have resolved and biological parameters have returned to normal.

If patients show early signs of corticosteroid dependency or have the previously mentioned risk factors (splenomegaly, low glycosylated ferritin, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or young age at AOSD onsetCitation16,Citation25), methotrexate could be considered early for its steroid-sparing effect. Usually, methotrexate (7.5–20 mg/week) enables complete remission of the disease (70%) or at least a significant reduction of daily corticosteroid intake.Citation29 Methotrexate has a similar effect on systemic and arthritic AOSD.Citation17,Citation29 Blood count, renal function, and liver enzymes should be monitored before initiation of methotrexate and then every 1–2 months.Citation71 If methotrexate fails to control the disease, other DMARDs could be considered. However, growing evidence suggests using targeted biologic therapies as early second-line treatment.

Refractory AOSD

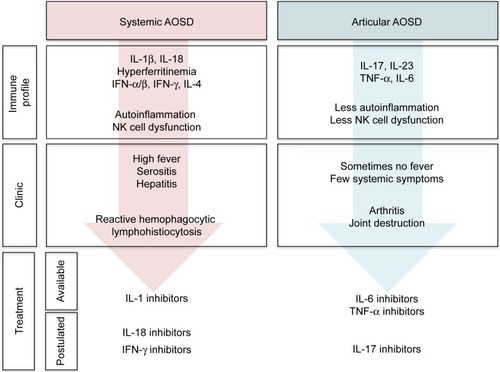

It is becoming increasingly apparent that AOSD patients fall into two distinct subsets, ie, those presenting with systemic features and those presenting with prominent arthritis.Citation10,Citation13–Citation15 These findings are supported by molecular evidence, cytokine profiles, clinical course, and response to treatment (). In AOSD, such as in systemic-onset JIA, it remains unclear whether the two subsets of the disease are temporally related (biphasic disease)Citation18 or present since the disease onset.

Figure 2 Two subtypes of adult-onset Still’s disease.

Predictive factors for a prominent articular pattern include female sex, proximal arthritis at disease onset, thrombocytosis, and corticosteroid dependency, whereas high fever, high levels of liver enzymes, or high acute phase reactants are more likely to be associated with a systemic pattern of AOSD.Citation72–Citation74 Other clues to identify the systemic subtype of AOSD are the following: thrombocytopenia, RHL, and hyperferritinemia. Although the cytokine dosage is not performed in routine care, IL-18, interferon-γ, IL-10, and IL-4 are associated with systemic AOSD whereas IL-6, IL-17, and IL-23 are associated with arthritic AOSD.Citation15,Citation74,Citation75 This dichotomy may be of the utmost importance for the management of AOSD patients, as patients falling into one of the two categories should benefit from different treatments.Citation10,Citation13

Patients with systemic AOSD are more likely to be responders to first-line corticosteroid therapy. In the case of refractory systemic AOSD, IL-1 antagonists (mostly anakinra) should be considered first as they have proved to be dramatically more efficient for systemic symptoms than for articular features.Citation16,Citation17,Citation35,Citation76 Anakinra is used at 100 mg/day via subcutaneous injection. Once the disease is controlled and the biological parameters have returned to normal, subcutaneous injections can be spaced. The most commonly reported adverse event with anakinra has been self-limiting erythema at the injection site. Unlike anakinra, anti-TNF-α agents usually have a less sustained effect on systemic symptoms.

Tocilizumab should be considered as an alternative to IL-1 antagonists, particularly when articular signs such as joint erosion accompany systemic symptoms.Citation10,Citation13,Citation77 Nevertheless, tocilizumab has been less widely used in treating AOSD and should actually be used only if anti-IL-1 treatments fail to control the disease or if relapses occur during weaning of anti-IL-1. Tocilizumab is given at a dosage of 5–8 mg/kg body weight every 2–4 weeks. Nevertheless, larger randomized studies are still needed to further determine the optimal therapeutic scheme for tocilizumab.

In patients with articular refractory AOSD, anti-TNF-α should be the preferred treatment.Citation10,Citation13,Citation77,Citation78 Infliximab, given with a therapeutic scheme similar to that used for rheumatoid arthritis (ie, 3–5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6, and then once every 8 weeks), seems to have better efficacy than etanercept, but larger studies are required to compare these two molecules. Since available data on the efficacy of adalimumab in AOSD are lacking, it cannot be recommended so far. In the case of failure of anti-TNF-α, tocilizumab should be considered first as it has proven efficient for both the articular and systemic features of AOSD.Citation10,Citation13 If tocilizumab fails, anakinra may be tried.

Finally, it should be noted that, in an effort to standardize therapeutic management and evaluate comparative effectiveness in an observational setting, the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance has developed four consensus treatment plans for systemic-onset JIA.Citation22 These plans include a glucocorticoid plan, a methotrexate plan, an anakinra plan, and a tocilizumab plan. As no guidelines are available for AOSD, this consensus plan should be of help for physicians dealing with new-onset AOSD.

Life-threatening complications of AOSD

Reactive hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

RHL corresponds to an uncontrollable activation of the reticuloendothelial system leading to phagocytosis of hematopoietic cells by activated tissue macrophages. In AOSD, RHL has been reported to have an incidence of 12%–17%.Citation79–Citation81 Evidence for occult RHL in a substantial proportion of patients with AOSD (up to 50%) supports the possibility that RHL and AOSD could represent the same disease within a continuum of severity.Citation82,Citation83 Considering all the underlying causes, the mortality rate for RHL ranges between 10% and 22%.Citation84–Citation86 The clinical picture and diagnostic criteria are presented in .Citation81 Although RHL features resemble those of AOSD, differences exist and may help the early recognition of RHL during AOSD:Citation83 the fever pattern is mostly non-remitting in RHL; there are less central nervous system involvement and hepatosplenomegaly during AOSD flare-ups than during RHL; and neutrophil and platelet counts are elevated in AOSD whereas they are low in RHL. Notably, a rapid decrease in leukocyte count or the rapid appearance of an hypertriglyceridemia may alert the physician on the onset of RHL complicating previously diagnosed AOSD. Hypofibrinogenemia is also one of the most important clues indicating RHL, since AOSD patients are more likely to have hyperfibrinogenemia due to the underlying inflammatory state. Hyperferritinemia is difficult to interpret in an AOSD patient because an acute increase in total and glycosylated serum ferritin can indicate a flare-up of AOSD or RHL. Bone marrow aspiration is the gold standard for diagnosis of RHL. It is not to be performed systematically but can be required in atypical cases and when there is a diagnostic dilemma.

Table 3 Diagnostic criteria for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

Treatment of RHL in AOSD patients has mostly been empirical and has consisted of intravenous pulsed corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin.Citation83 Several immunosuppressive drugs have also been used, including cyclosporine A, mycophenolate mofetil, or etoposide.Citation83,Citation87 More recently, several authors have reported on the successful management of RHL complicating adult or pediatric Still’s disease using IL-1 antagonists.Citation88–Citation91 It is possible that higher doses of anakinra are required to treat Still’s disease-associated RHL (ie, 100 mg/6 hours).Citation91 On the contrary, anti-TNF-α has proven ineffective or even harmful in treating RHL. Yet, several cases of RHL associated with etanercept have been reported in patients with AOSD.Citation88,Citation92 Finally, tocilizumab has been reported to be effective in the management of AOSD-related RHL, but these preliminary results still need to be confirmed.Citation93

Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy

Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) is characterized by an unregulated overactivation of the coagulation system. Fewer than ten cases have been reported in the setting of AOSD.Citation83 However, the diagnosis can be challenging since the clinical picture may mimic sepsis and DIC may complicate AOSD-related RHL.Citation94–Citation96 The reported efficient treatments of AOSD-associated DIC include prednisolone,Citation97 cyclosporine A,Citation96,Citation98 anakinra,Citation49 and tocilizumab.Citation99 So far, since only few data are available, it is not possible to recommend one or another molecule. Nevertheless, taking into account the morbidity of DIC, it seems reasonable to propose early therapy with anti-IL-1 or anti-IL-6 to AOSD patients who do not respond rapidly to corticosteroids.Citation96,Citation98

Myocarditis

We recently described four previously unreported cases of AOSD-related myocarditis and reviewed 20 other cases from the literature (Gerfaud-Valentin et al MedicineCitation100). Myocarditis was an early life-threatening complication of AOSD occurring within the first year after the disease onset and affecting younger patients, mostly males. All the patients were given high-dose corticosteroids (either intravenous pulses or 1 mg/kg body weight). Intravenous immunoglobulins were added in 6/24 patients, methotrexate in 5/24, and anti-TNF-α in 3/24. In addition, one patient received cyclophosphamide and another received anakinra (100 mg/day). All but one had a favorable outcome, giving a fatality rate of about 4%. Thus, AOSD-associated myocarditis can be life-threatening but has a good prognosis when recognized early and efficiently treated. High-dose corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment. Whether the other treatments are useful cannot be determined on the basis of this retrospective study, but in our experience, intravenous immunoglobulin seems to be useful and methotrexate steroid-sparing.

Thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura

About ten cases of AOSD-related thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) have been reported.Citation83 The pathophysiologic link between TTP and AOSD remains unknown. The clinical sign that should alert the clinician is acute visual loss. Early detection of TTP is required because it is associated with high morbidity and mortality.Citation101 Delayed treatment of TTP may lead to renal failure, brain edema, and death.Citation102,Citation103 Thrombocytopenia and unexplained microangiopathic hemolytic anemia are arguments for a diagnosis of TTP during AOSD.Citation104 Plasma exchange is always required in the event of AOSD-associated TTP. Additional drugs have been used with success, such as corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, or rituximab.Citation101,Citation103 Only one author has reported on successful treatment of AOSD-related TTP using tocilizumab, which seemed to be efficient in treating both TTP and the underlying refractory AOSD.Citation105

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage is a rare life-threatening complication of AOSD characterized by accumulation of erythrocytes in the lung alveolar spaces. Whether diffuse alveolar hemorrhage is a specific complication of AOSD or is coincidental remains unclear. Clinicians should think about diffuse alveolar hemorrhage when AOSD patients present with hemoptysis, cough, and dyspnea progressing to respiratory distress, together with falling hematocrit and hemorrhagic bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Therapeutic options include an intravenous pulse of high-dose methylprednisolone (1 g/day for 5 days), plasma exchange, or intravenous cyclophosphamide.Citation106,Citation107

AOSD and pregnancy

We recently reviewed the link between AOSD and pregnancy.Citation34 In the subset of women without previously known AOSD, the disease occurred mainly during the first or second trimester. Due to flares, some cases were complicated by oligohydramnios or prematurity. No life-threatening complications were reported. In the second subset of women with known AOSD, flares were less frequent and more likely to occur during the second trimester and the postpartum period. Of note, data concerning preventive treatment are controversial and do not allow guidelines or recommendations.Citation34,Citation108 Treatment of AOSD flares during pregnancy always included prednisone at a dosage of 0.5–1 mg/kg body weight. The safety of corticosteroids has been established for usual dosages, but their effect at higher dosages remains unclear.Citation109 In our previous article, it was not possible to state whether obstetric complications were due to the treatment or to the underlying disease.Citation34 Thus, multidisciplinary expertise is required when corticosteroids are required. In some cases, intravenous immunoglobulins has been added but their effect on the outcome cannot be clearly determined.Citation33,Citation34 Although NSAIDs have been used, they are not recommended during pregnancy, particularly after week 24. Anakinra was used during three pregnancies in patients with AOSD. Both the outcome of the AOSD and the pregnancies were positive. The disease was controlled in all three cases and the children were born at term and healthy.Citation110,Citation111 Finally, close multidisciplinary monitoring before, during, and after pregnancy is required for women with AOSD.

Conclusion

Adult-onset Still’s disease is a complex disease with a polymorphic clinical presentation. In some cases, AOSD is as simple as a unique flare easily cured by NSAIDs or short-course corticosteroid therapy. On another hand, AOSD can present with stormy systemic features and lead to life-threatening complications (such as RHL) or as a chronic articular disease that may be either indolent or destructive. Recent advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of AOSD and the availability of anti-cytokine-targeted treatments have given rise to more personalized treatments. In the near future, understanding of AOSD will probably benefit further from wide genetic analyses. Targeted biologic therapies seem to have a dramatic effect when given as first-line treatment in systemic-onset JIA. Results from ongoing observational studies and future prospective trials may lead to the recommendation of earlier use of these treatments in AOSD. Finally, the management of AOSD will also benefit from the release of new targeted biotherapies, such as anti-IL-18 or anti-IL-17.

Acknowledgments

YJ acknowledges the Foundation for the Development of Internal Medicine in Europe, the Société Nationale Française de Médecine Interne, Groupama Fundation, and Genzyme for their help in funding his PhD research project. YJ is supported by a “poste d’accueil” at INSERM.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BywatersEGStill’s disease in the adultAnn Rheum Dis19713021211335315135

- StillGFOn a form of chronic joint disease in childrenMed Chir Trans1897804760.9

- EfthimiouPPaikPKBieloryLDiagnosis and management of adult onset Still’s diseaseAnn Rheum Dis200665556457216219707

- TanakaSMatsumotoYOhnishiHComparison of clinical features of childhood and adult onset Still’s diseaseRyūmachi Rheum1991315511518 Japanese

- UppalSSPandeIRKumarAAdult onset Still’s disease in northern India: comparison with juvenile onset Still’s diseaseBr J Rheumatol19953454294347788171

- LuthiFZuffereyPHoferMFSoAK“Adolescent-onset Still’s disease”: characteristics and outcome in comparison with adult-onset Still’s diseaseClin Exp Rheumatol200220342743012102485

- YamaguchiMOhtaATsunematsuTPreliminary criteria for classification of adult Still’s diseaseJ Rheumatol19921934244301578458

- FautrelBZingEGolmardJ-LProposal for a new set of classification criteria for adult-onset Still diseaseMedicine200281319420011997716

- MahroumNMahagnaHAmitalHDiagnosis and classification of adult Still’s diseaseJ Autoimmun201448493437

- Gerfaud-ValentinMJamillouxYIwazJSèvePAdult-onset Still’s diseaseAutoimmun Rev201413770872224657513

- McGonagleDMcDermottMFA proposed classification of the immunological diseasesPLoS Med200638e29716942393

- KastnerDLAksentijevichIGoldbach-ManskyRAutoinflammatory disease reloaded: a clinical perspectiveCell2010140678479020303869

- MariaATLe QuellecAJorgensenCTouitouIRivièreSGuilpainPAdult onset Still’s disease (AOSD) in the era of biologic therapies: dichotomous view for cytokine and clinical expressionsAutoimmun Rev8272014 Epub ahead of print

- CannaSWEditorial. Interferon-γ: friend or foe in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and adult Still’s diseaseArthritis Rheumatol20146651072107624470448

- ShimizuMNakagishiYYachieADistinct subsets of patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis based on their cytokine profilesCytokine201361234534823276493

- Gerfaud-ValentinMMaucort-BoulchDHotAAdult-onset Still disease: manifestations, treatments, outcome, and prognostic factors in 57 patientsMedicine (Baltimore)2014932919924646465

- FranchiniSDagnaLSalvoFAielloPBaldisseraESabbadiniMGEfficacy of traditional and biologic agents in different clinical phenotypes of adult-onset Still’s diseaseArthritis Rheum20106282530253520506370

- NigrovicPAReview: is there a window of opportunity for treatment of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis?Arthritis Rheumatol20146661405141324623686

- NigrovicPAMannionMPrinceFHAnakinra as first-line disease-modifying therapy in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: report of forty-six patients from an international multicenter seriesArthritis Rheum201163254555521280009

- VastertSJde JagerWNoordmanBJEffectiveness of first-line treatment with recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in steroid-naive patients with new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results of a prospective cohort studyArthritis Rheumatol20146641034104324757154

- MoulisGSaillerLAstudilloLPugnetGArletPMay anakinra be used earlier in adult onset Still disease?Clin Rheumatol201029101199120020428907

- DeWittEMKimuraYBeukelmanTConsensus treatment plans for new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritisArthritis Care Res201264710011010

- PaySTürkçaparNKalyoncuMA multicenter study of patients with adult-onset Still’s disease compared with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritisClin Rheumatol200625563964416365690

- NagashimaTIwamotoMMatsumotoKMinotaSInterleukin-18 in adult-onset Still’s disease: treatment target or disease activity indicator?Intern Med201251444922333388

- KimH-ASungJ-MSuhC-HTherapeutic responses and prognosis in adult-onset Still’s diseaseRheumatol Int20123251291129821274538

- PouchotJSampalisJSBeaudetFAdult Still’s disease: manifestations, disease course, and outcome in 62 patientsMedicine (Baltimore)19917021181362005777

- MitamuraMTadaYKoaradaSCyclosporin A treatment for Japanese patients with severe adult-onset Still’s diseaseMod Rheumatol2009191576318839270

- NakamuraHOdaniTShimizuYTakedaTKikuchiHUsefulness of tacrolimus for refractory adult-onset Still’s disease: report of six casesMod Rheumatol20141815

- FautrelBBorgetCRozenbergSCorticosteroid sparing effect of low dose methotrexate treatment in adult Still’s diseaseJ Rheumatol19992623733789972972

- VignesSWechslerBAmouraZIntravenous immunoglobulin in adult Still’s disease refractory to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugsClin Exp Rheumatol19981632952989631752

- PermalSWechslerBCabaneJPerrotSBlumLImbertJCTreatment of Still’s disease in adults with intravenous immunoglobulinsRev Med Interne1995164250254 French7746963

- EmmeneggerUFreyUReimersAHyperferritinemia as indicator for intravenous immunoglobulin treatment in reactive macrophage activation syndromesAm J Hematol200168141011559930

- LiozonELyKAubardYVidalEIntravenous immunoglobulins for adult Still’s disease and pregnancyRheumatology199938101024102510534562

- Gerfaud-ValentinMHotAHuissoudCDurieuIBroussolleCSevePAdult-onset Still’s disease and pregnancy: about ten cases and review of the literatureRheumatol Int201434686787123624554

- LequerréTQuartierPRoselliniDInterleukin-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) treatment in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis or adult onset Still disease: preliminary experience in FranceAnn Rheum Dis200867330230817947302

- BenucciMLiGFDel RossoAManfrediMAdalimumab (anti-TNF-alpha) therapy to improve the clinical course of adult-onset Still’s disease: the first case reportClin Exp Rheumatol200523573316173267

- FelsonDTAndersonJJBoersMAmerican College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritisArthritis Rheum19953867277357779114

- HusniMEMaierALMeasePJEtanercept in the treatment of adult patients with Still’s diseaseArthritis Rheum20024651171117612115220

- CavagnaLCaporaliREpisOBobbio-PallaviciniFMontecuccoCInfliximab in the treatment of adult Still’s disease refractory to conventional therapyClin Exp Rheumatol200119332933211407090

- KraetschHGAntoniCKaldenJRMangerBSuccessful treatment of a small cohort of patients with adult onset of Still’s disease with infliximab: first experiencesAnn Rheum Dis200160Suppl 3iii55iii5711890655

- KokkinosAIliopoulosAGrekaPEfthymiouAKatsilambrosNSfikakisPPSuccessful treatment of refractory adult-onset Still’s disease with infliximab. A prospective, non-comparative series of four patientsClin Rheumatol2004231454914749983

- FautrelBSibiliaJMarietteXCombeBClub Rhumatismes et InflammationTumour necrosis factor alpha blocking agents in refractory adult Still’s disease: an observational study of 20 casesAnn Rheum Dis200564226226615184196

- AikawaNERibeiroACSaadCGIs anti-TNF switching in refractory Still’s disease safe and effective?Clin Rheumatol20113081129113421465126

- KanekoKKaburakiMMuraokaSExacerbation of adult-onset Still’s disease, possibly related to elevation of serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha after etanercept administrationInt J Rheum Dis2010134e67e6921199457

- AgarwalSMoodleyJAjani GoelGTheilKSMahmoodSSLangRSA rare trigger for macrophage activation syndromeRheumatol Int201131340540719834709

- Vasques GodinhoFMParreira SantosMJCanas da SilvaJRefractory adult onset Still’s disease successfully treated with anakinraAnn Rheum Dis200564464764815374853

- FitzgeraldAALeclercqSAYanAHomikJEDinarelloCARapid responses to anakinra in patients with refractory adult-onset Still’s diseaseArthritis Rheum20055261794180315934079

- KallioliasGDGeorgiouPEAntonopoulosIAAndonopoulosAPLiossisSNAnakinra treatment in patients with adult-onset Still’s disease is fast, effective, safe and steroid sparing: experience from an uncontrolled trialAnn Rheum Dis200766684284317513574

- KötterIWackerAKochSAnakinra in patients with treatment-resistant adult-onset Still’s disease: four case reports with serial cytokine measurements and a review of the literatureSemin Arthritis Rheum200737318919717583775

- LaskariKTzioufasAGMoutsopoulosHMEfficacy and long-term follow-up of IL-1R inhibitor anakinra in adults with Still’s disease: a case-series studyArthritis Res Ther2011133R9121682863

- RudinskayaATrockDHSuccessful treatment of a patient with refractory adult-onset Still disease with anakinraJ Clin Rheumatol20039533033217041487

- NordströmDKnightALuukkainenRBeneficial effect of interleukin 1 inhibition with anakinra in adult-onset Still’s disease. An open, randomized, multicenter studyJ Rheumatol201239102008201122859346

- Lo GulloACarusoAPipitoneNMacchioniPPazzolaGSalvaraniCCanakinumab in a case of adult onset Still’s disease: efficacy only on systemic manifestationsJoint Bone Spine201481437637724462130

- KontziasAEfthimiouPThe use of canakinumab, a novel IL-1β long-acting inhibitor, in refractory adult-onset Still’s diseaseSemin Arthritis Rheum201242220120522512815

- RupertoNQuartierPWulffraatNA phase II, multicenter, open-label study evaluating dosing and preliminary safety and efficacy of canakinumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis with active systemic featuresArthritis Rheum201264255756721953497

- RupertoNBrunnerHIQuartierPTwo randomized trials of canakinumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritisN Engl J Med2012367252396240623252526

- SwartJFBarugDMöhlmannMWulffraatNMThe efficacy and safety of interleukin-1-receptor antagonist anakinra in the treatment of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritisExpert Opin Biol Ther201010121743175220979564

- QuartierPAllantazFCimazRA multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ANAJIS trial)Ann Rheum Dis201170574775421173013

- PuéchalXDeBandtMBerthelotJ-MTocilizumab in refractory adult Still’s diseaseArthritis Care Res2011631155159

- CiprianiPRuscittiPCarubbiFTocilizumab for the treatment of adult-onset Still’s disease: results from a case seriesClin Rheumatol2014331495524005839

- ElkayamOJiriesNDranitzkiZTocilizumab in adult-onset Still’s disease: the Israeli experienceJ Rheumatol201441224424724429168

- Ortiz-SanjuánFBlancoRCalvo-RioVEfficacy of tocilizumab in conventional treatment-refractory adult-onset Still’s disease: multicenter retrospective open-label study of thirty-four patientsArthritis Rheumatol20146661659166524515813

- De BenedettiFBrunnerHIRupertoNRandomized trial of tocilizumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritisN Engl J Med2012367252385239523252525

- YokotaSImagawaTMoriMEfficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal phase III trialLancet20083719617998100618358927

- CushJJMedsgerTAJrChristyWCHerbertDCCoopersteinLAAdult-onset Still’s disease. Clinical course and outcomeArthritis Rheum19873021861943827959

- WoutersJMvan de PutteLBAdult-onset Still’s disease; clinical and laboratory features, treatment and progress of 45 casesQ J Med198661235105510653659248

- KongX-DXuDZhangWZhaoYZengXZhangFClinical features and prognosis in adult-onset Still’s disease: a study of 104 casesClin Rheumatol20102991015101920549276

- KimYJKooBSKimY-GLeeC-KYooBClinical features and prognosis in 82 patients with adult-onset Still’s diseaseClin Exp Rheumatol2014321283324050706

- KoizumiRTsukadaYIdeuraHUekiKMaezawaANojimaYTreatment of adult Still’s disease with dexamethasone, an alternative to prednisoloneScand J Rheumatol200029639639811132211

- HotATohM-LCoppéréBReactive hemophagocytic syndrome in adult-onset Still disease: clinical features and long-term outcome: a case-control study of 8 patientsMedicine (Baltimore)2010891374620075703

- PavySConstantinAPhamTMethotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: clinical practice guidelines based on published evidence and expert opinionJoint Bone Spine200673438839516626993

- ChenD-YLanJ-LLinF-JHsiehT-YProinflammatory cytokine profiles in sera and pathological tissues of patients with active untreated adult onset Still’s diseaseJ Rheumatol200431112189219815517632

- FujiiTNojimaTYasuokaHCytokine and immunogenetic profiles in Japanese patients with adult Still’s disease. Association with chronic articular diseaseRheumatology200140121398140411752512

- IchidaHKawaguchiYSugiuraTClinical manifestations of adult-onset Still’s disease presenting with erosive arthritis: association with low levels of ferritin and IL-18Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken)1072013 Epub ahead of print

- ShimizuMYokoyamaTYamadaKDistinct cytokine profiles of systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated macrophage activation syndrome with particular emphasis on the role of interleukin-18 in its pathogenesisRheumatology20104991645165320472718

- GattornoMPicciniALasiglièDThe pattern of response to anti-interleukin-1 treatment distinguishes two subsets of patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritisArthritis Rheum20085851505151518438814

- PouchotJArletJ-BBiological treatment in adult-onset Still’s diseaseBest Pract Res Clin Rheumatol201226447748723040362

- LinY-TWangC-TGershwinMEChiangB-LThe pathogenesis of oligoarticular/polyarticular vs systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritisAutoimmun Rev201110848248921320644

- MellinsEDMacaubasCGromAAPathogenesis of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: some answers, more questionsNat Rev Rheumatol20117741642621647204

- ArletJ-BLeTHMarinhoAReactive haemophagocytic syndrome in adult-onset Still’s disease: a report of six patients and a review of the literatureAnn Rheum Dis200665121596160116540551

- RavelliAGromAABehrensEMCronRQMacrophage activation syndrome as part of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: diagnosis, genetics, pathophysiology and treatmentGenes Immun201213428929822418018

- BehrensEMBeukelmanTPaesslerMCronRQOccult macrophage activation syndrome in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritisJ Rheumatol20073451133113817343315

- EfthimiouPKadavathSMehtaBLife-threatening complications of adult-onset Still’s diseaseClin Rheumatol201433330531424435354

- SilvaCASilvaCHRobazziTCMacrophage activation syndrome associated with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritisJ Pediatr (Rio J)2004806517522 Portuguese15622430

- RamananAVSchneiderRMacrophage activation syndrome following initiation of etanercept in a child with systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol200330240140312563702

- TristanoAGMacrophage activation syndrome: a frequent but under-diagnosed complication associated with rheumatic diseasesMed Sci Monit2008143RA27RA3618301366

- MizrahiMBen-ChetritERelapsing macrophage activating syndrome in a 15-year-old girl with Still’s disease: a case reportJ Med Case Rep2009313820062775

- PamukONPamukGEUstaUCakirNHemophagocytic syndrome in one patient with adult-onset Still’s disease. Presentation with febrile neutropeniaClin Rheumatol200726579780016550302

- KellyARamananAVA case of macrophage activation syndrome successfully treated with anakinraNat Clin Pract Rheumatol200841161562018825135

- BruckNSuttorpMKabusMHeubnerGGahrMPesslerFRapid and sustained remission of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated macrophage activation syndrome through treatment with anakinra and corticosteroidsJ Clin Rheumatol2011171232721169853

- RecordJLBeukelmanTCronRQCombination therapy of abatacept and anakinra in children with refractory systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a retrospective case seriesJ Rheumatol201138118018121196588

- SternARileyRBuckleyLWorsening of macrophage activation syndrome in a patient with adult onset Still’s disease after initiation of etanercept therapyJ Clin Rheumatol20017425225617039144

- KobayashiMTakahashiYYamashitaHKanekoHMimoriABenefit and a possible risk of tocilizumab therapy for adult-onset Still’s disease accompanied by macrophage-activation syndromeMod Rheumatol2011211929620737186

- AellenPRaccaudOWaldburgerMChamotAMGersterJCStill’s disease in adults with disseminated intravascular coagulationSchweiz Rundsch Med Prax19918015376378 German2031109

- AraiYHandaTMitaniKAdult-onset Still disease presenting with disseminated intravascular coagulationRinsho Ketsueki2004454316318 Japanese15168449

- ParkJ-HBaeJHChoiY-SAdult-onset Still’s disease with disseminated intravascular coagulation and multiple organ dysfunctions dramatically treated with cyclosporine AJ Korean Med Sci200419113714114966357

- YokoyamaMSuwaAShinozawaTA case of adult onset Still’s disease complicated with adult respiratory distress syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulationNihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi1995182207214 Japanese7553055

- MoriTTanigawaMIwasakiECyclosporine therapy of adult onset Still’s disease with disseminated intravascular coagulationNihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi1993342147152 Japanese

- MatsumotoKNagashimaTTakatoriSGlucocorticoid and cyclosporine refractory adult onset Still’s disease successfully treated with tocilizumabClin Rheumatol200928448548719184270

- Gerfaud-ValentinMSèvePIwazJMyocarditis in adult-onset Still diseaseMedicine. (Baltimore)2014931728028925398063

- PerezMGRodwigFRJrChronic relapsing thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in adult onset Still’s diseaseSouth Med J2003961464912602713

- MasuyamaAKobayashiHKobayashiYA case of adult-onset Still’s disease complicated by thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura with retinal microangiopathy and rapidly fatal cerebral edemaMod Rheumatol201323237938522623015

- SayarliogluMSayarliogluHOzkayaMBalakanOUcarMAThrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome and adult onset Still’s disease: case report and review of the literatureMod Rheumatol200818440340618427722

- OnundarsonPTRoweJMHealJMFrancisCWResponse to plasma exchange and splenectomy in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. A 10-year experience at a single institutionArch Intern Med199215247917961558437

- SumidaKUbaraYHoshinoJEtanercept-refractory adult-onset Still’s disease with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura successfully treated with tocilizumabClin Rheumatol201029101191119420225049

- CheemaGSQuismorioFPPulmonary involvement in adult-onset Still’s diseaseCurr Opin Pulm Med19995530530910461535

- SariIBirlikMBinicierOA case of adult-onset Still’s disease complicated with diffuse alveolar hemorrhageJ Korean Med Sci200924115515719270830

- Le LoëtXDaragonADuvalCThomineELauretPHumbertGAdult onset Still’s disease and pregnancyJ Rheumatol1993207115811618371209

- LockshinMDSammaritanoLRCorticosteroids during pregnancyScand J Rheumatol Suppl19981071361389759153

- Fischer-BetzRSpeckerCSchneiderMSuccessful outcome of two pregnancies in patients with adult-onset Still’s disease treated with IL-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra)Clin Exp Rheumatol20112961021102322153586

- BergerCTRecherMSteinerUHauserTMA patient’s wish: anakinra in pregnancyAnn Rheum Dis200968111794179519822718

- GiampietroCRideneMLequerreTAnakinra in adult-onset Still’s disease: long-term treatment in patients resistant to conventional therapyArthritis Care Res2013655822826