Abstract

Background and objectives

Epidemiological investigations of the relationship between oral contraceptives and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) risk have reported controversial results. Therefore, a meta-analysis of case-control or cohort studies was performed to evaluate the role of oral contraceptives in relation to risk of developing RA.

Methods

Eligible studies were identified from databases PubMed and EMBASE by searching and reviewing references. Random effect models were utilized to summarize the relative risk (RR) estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

A total of 12 case-control studies and five cohort studies were eligible for our analysis. No statistically significant association was observed between oral contraceptives and RA risk (RR=0.88, 95% CI=0.75–1.03). In the subgroup of geographic area, a decreased risk of borderline significance was observed for oral contraceptive users in European studies (RR=0.79, 95% CI=0.62–1.01), but this association did not emerge in the North American studies group (RR=0.99, 95% CI=0.81–1.21). No evidence for publication bias was detected (P for Egger’s test =0.231).

Conclusion

Our results of meta-analysis do not support the hypothesis of a protective effect of oral contraceptives on the risk for RA in women.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common chronic systemic inflammatory autoimmune disorder of the synovial tissues and joints, which affects approximately 1% of the adult population all over the world.Citation1–Citation3 Although the etiology of RA remains elusive, an increasing body of evidence suggests that sex hormones may play a role in RA pathogenesis. RA occurs approximately twice to thrice as often in women as in men.Citation4 In addition, RA symptoms tend to diminish during pregnancy and aggravate postpartum.Citation5,Citation6 Owing to this background, recent epidemiological studies evaluated the risk of RA in users of oral contraceptives (OCs) versus nonusers.Citation4,Citation7–Citation42 However, a conflicting picture on this issue was presented in these studies. Given that the vast majority of studies were of small sample size and characterized by low statistical power, these findings may be detected by chance. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies to summarize the evidence and provide an accurate estimation of association between OCs use and RA risk.

Material and methods

Search strategy

Studies assessing the relationship between RA risk and OCs were identified in PubMed and EMBASE databases using the following search terms: (“oral contraceptives” OR “exogenous hormones” OR “hormone”) AND (“rheumatoid arthritis” OR “RA”) AND (“risk” OR “risk factor”). The latest date for this search was June 13, 2014. The bibliographies of relevant articles were checked by a manual search for additional publications of interest.

Inclusion criteria

We adopted the following inclusion criteria: (1) the report described a case-control or cohort study; (2) the report provided the relative risk (RR) or odds ratio with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI), or sufficient information to calculate them (ie, the distribution of exposure); (3) when multiple reports involved the same study population, only the most informative one was identified for this analysis. We excluded the conference abstracts, case series, letter to editors, reviews, meta-analysis, and cross-sectional studies and we also excluded those studies that involved family cases in their subjects.

Data collection

We extracted information on the first author, sites where the study was performed, age of study population, number of subjects (cases, controls, or cohort size), study design, years of case diagnosis or cohort enrollment, length of follow-up for cohort studies, the method of OCs exposure assessment, the adjusted RR estimates with corresponding 95% CIs from multivariable model, match factors, and covariates adjusted for in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using STATA version 12 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). The measure of interest was the RR. ORs were directly considered as RRs, because the prevalence of RA was rare.Citation43 A random-effect model with the method of DerSimonian and Laird, which incorporates the heterogeneity across studies, was employed to calculate the pooled RR.Citation44 We evaluated the heterogeneity using the Cochran’s Q and I2 statistics.Citation45,Citation46 Significant heterogeneity was found as P-value for heterogeneity <0.10 or I2>50%. Stratified analyses were performed according to study design (case-control vs nested case-control vs cohort studies), source of control (population-based vs hospital-based case-control studies), and geographic area (European vs North American studies). Also, a sensitivity analysis was performed to investigate the influence of potential confounding (ie, age, smoking, parity/pregnancy, age at menarche, body mass index (BMI), social class, and marital status) on RA risk. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of individual studies on the overall results by excluding one study at a time. Potential publication bias was evaluated using Begg’s funnel plots and quantified by the Egger’s test (a P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant).Citation47,Citation48

The unit of the meta-analysis was a single comparison of OCs users versus nonusers. When a study presented separate RRs for different duration of OCs use versus nonuse, the overall risk estimate for OCs use versus nonuse was calculated from these separate RRs with the method proposed by Hamling et al.Citation49 This method is utilized to combine estimates using the same reference category. Also, the association between estimates is taken into account. In the analyses on duration of OCs use, we define short-term use as <5 years, and long-term use ≥5 years. Among the included studies, two studies that reported long-term use as ≥4 years were also included in this meta-analysis. Then, we performed an analysis that excluded those two studies to investigate the robustness of the results of long-term OCs use.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

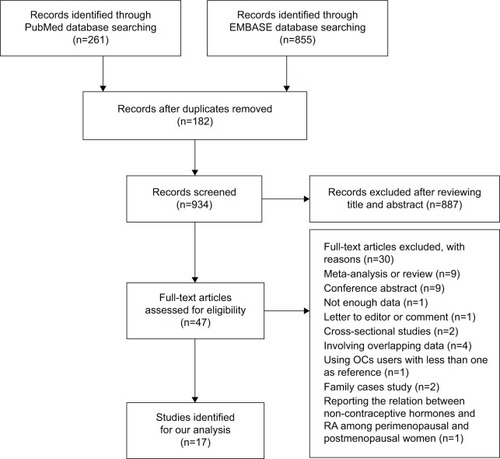

Based on our search terms, a total of 1,116 publications were identified in PubMed and EMBASE databases. shows the flowchart of literature inclusion and exclusion. We identified 47 publications for full-text evaluation, of which 30 publications were further excluded because they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria (ie, conference abstracts,Citation34–Citation42 meta-analyses/reviews,Citation50–Citation58 letters to editor/comments,Citation59 cross-sectional studies,Citation29,Citation30 providing insufficient data,Citation28 involving the same study population or overlapped data,Citation8,Citation31–Citation33 involving family cases,Citation13,Citation17 reporting the relationship between noncontraceptive hormones and RA among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women,Citation11 and using OCs users with less than one patient as referenceCitation9). Therefore, our meta-analysis was based on 17 publications, including 12 case-control and five cohort studies published between 1982 and 2010.Citation4,Citation7,Citation10,Citation12,Citation14–Citation16,Citation18–Citation27 All studies were published in English. The other characteristics of included studies are listed in .

Figure 1 The flowchart of literature selection.

Table 1 Descriptive characteristics of 17 included studies of RA risk with OCs use

Overall association of OCs use and RA risk

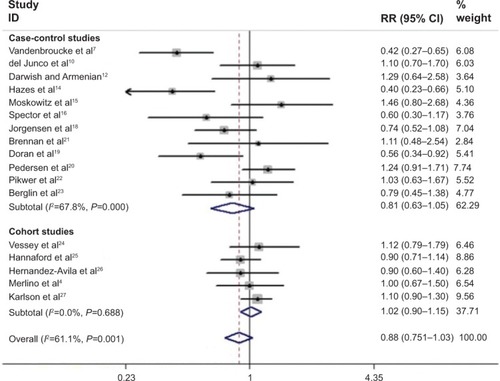

presents the study-specific and pooled RRs and 95% CIs of RA for OCs users versus nonusers. The summary estimates were 1.02 (95% CI=0.90–1.15, I2=0.0%, P for heterogeneity =0.688), 0.81 (95% CI=0.63–1.05, I2=66.4%, P for heterogeneity <0.001), and 0.88 (95% CI=0.75–1.03, I2=61.1%, P for heterogeneity =0.001) for cohort studies, case-control studies, and all studies, respectively. In further analysis, according to the type of controls for the case-control studies, similar trends with the overall result were observed in population-based case-control studies (RR=0.87, 95% CI=0.65–1.17, I2=47.1%, P for heterogeneity =0.093) and hospital-based case-control studies (RR=0.78, 95% CI=0.51–1.18, I2=77.3%, P for heterogeneity =0.001). Considering subgroups of geographic area, the combined estimate was 0.79 (95% CI=0.62–1.01, I2=67.6%, P for heterogeneity =0.001) in European studies and the corresponding estimate was 0.99 (95% CI=0.81–1.21, I2=37.7%, P for heterogeneity =0.155) in North American studies. Considering subgroups of matching or adjusted factors, the correlation of OCs use related with RA risk was not significantly modified by age, smoking, parity/pregnancy, age at menarche, BMI, social class, or marital status (). In the analyses on duration of OCs use, the pooled RRs were 0.84 (95% CI=0.56–1.27, I2=80.0%, P for heterogeneity <0.001) for short-term use and 0.84 (95% CI=0.64–1.10, I2=52.8%, P for heterogeneity =0.048) for long-term use.

Figure 2 Forest plots of RA risk and OCs use.

Table 2 Subgroup analyses of RRs for the association between RA risk and OCs use

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

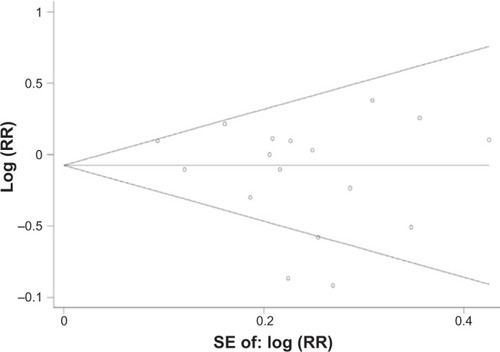

In the sensitivity analysis, we removed one study at a time to assess robustness of the overall results. The results of the sensitivity analysis are shown in . The Begg’s funnel plot does not show any asymmetry (). Also, no publication bias was ascertained by Egger’s test (P for Egger’s test =0.231).

Figure 3 Begg’s funnel plot (with pseudo 95% confidence limits) analysis to detect publication bias.

Table 3 Results of sensitivity analysis for RA risk with OCs use

Discussion

Female hormones have long been considered to play a role in human disease. Many epidemiologic studies that evaluated the relationship between OCs use and RA have yielded conflicting results, with inverse and positive correlations reported. To clarify this issue, five system reviews or meta-analyses have been published between 1989 and 1996.Citation52–Citation55,Citation57 However, the results from previous meta-analysis remain controversial. Romieu et al in their meta-analysis of nine case-control studies found no significant association between OCs use and RA risk (RR=0.79, 95% CI=0.58–1.08).Citation54 Spector and Hochberg reported that OCs use was associated with a decreased risk of RA (RR=0.73, 95% CI=0.61–0.85).Citation55 In 1996, Pladevall-Vila et al summarized the evidence of seven case-control and three cohort studies published before 1993.Citation57 The combined results showed that OCs use cannot decrease the risk of RA (RR=0.95, 95% CI=0.81–1.21).Citation57 Since 1993, more than ten original studies have proven or denied those findings.Citation17–Citation34 Therefore, an updated meta-analysis was undertaken. Specifically, in our study, we (1) included the studies published to date, (2) excluded the overlapped data, (3) analyzed the variables (ie, study design, source of control, geographic area, and matching or adjustment factors) across studies, (4) investigated how the RA risk changed with the dose effect of duration of OCs use, and (5) conducted sensitivity analyses and publication bias.

Our current meta-analysis of 12 case-control and five cohort studies suggested that use of OCs was not significantly associated with RA risk. The association was not significantly affected by study design, source of control, or matching/adjustment factors. However, subgroup meta-analyses of geographic area based on limited numbers of studies indicated that compared with nonusers, a decreased risk of borderline significance was observed for OCs users in European studies, but this association did not emerge in the North American studies group.

Another problematic OCs variable (ie, current use) has been evaluated by three case-control and two cohort studies.Citation7,Citation15,Citation21,Citation24,Citation26 All studies showed that there was a nonsignificant increase or decrease in RA risk emerged except in one hospital-based case-control study with 228 cases and 302 controls.Citation7 Vandenbroucke et al found a 55% reduction in RA risk among current users. However, the number of current users was small, and we cannot exclude the possibility that the finding, of a significant decreased risk for RA among current users, is a chance finding and should be interpreted with caution. Given that “current use” measures different time points with respect to the date of diagnosis (or date of interview for controls) in case-control versus prospective cohort studies, risk estimates of this variable cannot be pooled across study designs.

Heterogeneity is often a concern in a meta-analysis. In our meta-analysis, evidence of substantial heterogeneity across studies of the associations of OCs use with RA risk was observed. This finding was consistent with a previous meta-analysis published in 1996, which showed that the source of controls was the most important characteristic in accounting for the strong heterogeneity.Citation57 In our subgroup analyses by study design and source of controls, no significant heterogeneity was detected in cohort (I2=0.0%) or population-based case-control studies (I2=47.1%), but substantial heterogeneity was observed in hospital-based case-control studies (I2=77.3%). In hospital-based case-control studies, the choice of control populations differed markedly. The controls were women with a diagnosis of soft tissue rheumatism (bursitis, tenosynovitis, shoulder-hand syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome, low back pain, etc) or osteoarthritis (localized to knee, hip, or vertebrae) recruited from outpatient clinics of university hospitals or private clinics. Moreover, the included studies were conducted in different countries, where people may share little in terms of genetic background, lifestyles, and RA incidence. Thus, the characteristics of subjects and study design likely contributed to the observed heterogeneity.

To evaluate the effect of exposure duration, short-term use of OCs was defined as duration of <5 years, and long-term use as duration of ≥5 years. We found that no significant reduction in RA risk was associated with short-term or long-term use. Moreover, the relationship between dose of OCs use and RA risk has been addressed in a hospital-based case-control study with 135 cases and 378 controls.Citation14 Hazes et al defined the use of low-dose OCs as dose of <0.05 mg estrogen and high dose as dose of ≥0.05 mg estrogen, and found that the dose did not moderate the RR estimates. Evaluation of dose effect lends support for a causality of an association between exposure and disease, therefore, further investigation of OCs use with RA risk is needed with particular attention to duration and dose of OCs use.

Potential limitations of the present meta-analysis need to be addressed. First, because our analysis was mainly based on retrospective case-control studies, the observed null association may be masked by the recall and select biases originating from primary studies. Moreover, unmeasured or residual confounding is always a subject of major concern in observational studies. Although the results of subgroup analyses showed that the relationship between OCs use and RA risk was not influenced by the confounders such as age, smoking, parity/pregnancy, age at menarche, BMI, social class, or marital status, the likelihood that our finding resulted from other unmeasured confounders cannot be excluded. Second, we were unable to evaluate the components of OCs with RA risk. During the 1980s, OCs markedly differed from the ones used later on, eg, low estrogen, triphasic.Citation60 Therefore, the formulation of OCs with RA risk remains open to discussion. Third, the RA case identification was based on different diagnosis criteria. Both 1958 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and 1987 ACR criteria for RA were adopted in included studies. Thus, misclassification of subjects was possible and the relationship between OCs use and RA risk may be underestimated or overestimated. Furthermore, nowadays, RA classification criteria are updated by 2010 ACR classification criteria. Further evaluation of the relationship between OCs use and RA risk should adopt the new ACR classification criteria. Finally, publication bias could be a problem because studies with null effects are less likely to be published than those providing statistically significant results. Although no evidence of publication bias was detected by Egger’s test and Begg’s funnel plots in our meta-analysis, the estimation may not be accurate enough as the number of the included studies is relatively small.

In summary, findings of the present meta-analysis of 17 observational studies indicate that OC use cannot reduce the risk of RA. Yet, many questions still need to be addressed. Further large-scale prospective studies with emphasis on strict case definition based on the 2010 ACR classification criteria, formulation of OCs, duration of OCs use, dose of OCs use, and confounders are warranted to validate our findings.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- McInnesIBSchettGThe pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritisN Engl J Med2011365232205221922150039

- GibofskyAOverview of epidemiology, pathophysiology, and diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritisAm J Manag Care20121813 supplS295S30223327517

- KlareskogLCatrinaAIPagetSRheumatoid arthritisLancet2009373966465967219157532

- MerlinoLACerhanJRCriswellLAMikulsTRSaagKGEstrogen and other female reproductive risk factors are not strongly associated with the development of rheumatoid arthritis in elderly womenSemin Arthritis Rheum2003332728214625816

- HazesJMPregnancy and its effect on the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritisAnn Rheum Dis199150271721998392

- SilmanAKayABrennanPTiming of pregnancy in relation to the onset of rheumatoid arthritisArthritis Rheum19923521521551734904

- VandenbrouckeJPValkenburgHABoersmaJWOral contraceptives and rheumatoid arthritis: further evidence for a preventive effectLancet1982283038398426126710

- LinosAWorthingtonJWO’FallonWMKurlandLTCase-control study of rheumatoid arthritis and prior use of oral contraceptivesLancet198318337129913006134094

- AllebeckPAhlbomALjungströmKAllanderEDo oral contraceptives reduce the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis? A pilot study using the Stockholm County medical information systemScand J Rheumatol19841321401466740269

- del JuncoDJAnnegersJFLuthraHSCoulamCBKurlandLTDo oral contraceptives prevent rheumatoid arthritis?JAMA198525414193819414046123

- VandenbrouckeJPWittemanJCValkenburgHANoncontraceptive hormones and rheumatoid arthritis in perimenopausal and postmenopausal womenJAMA198625510129913033944948

- DarwishMJArmenianHKA case-control study of rheumatoid arthritis in LebanonInt J Epidemiol19871634204243667041

- HazesJMSilmanAJBrandRSpectorTDWalkerDJVandenbrouckeJPInfluence of oral contraception on the occurrence of rheumatoid arthritis in female sibsScand J Rheumatol19901943063102402603

- HazesJMDijkmansBCVandenbrouckeJPde VriesRRCatsAReduction of the risk of rheumatoid arthritis among women who take oral contraceptivesArthritis Rheum19903321731792306289

- MoskowitzMAJickSSBurnsideSThe relationship of oral contraceptive use to rheumatoid arthritisEpidemiology1990121531562073503

- SpectorTDRomanESilmanAJThe pill, parity, and rheumatoid arthritisArthritis Rheum19903367827892363734

- BrennanPSilmanAJAn investigation of gene–environment interaction in the etiology of rheumatoid arthritisAm J Epidemiol199414054534608067337

- JorgensenCPicotMCBolognaCSanyJOral contraception, parity, breast feeding, and severity of rheumatoid arthritisAnn Rheum Dis199655294988712873

- DoranMFCrowsonCSO’FallonWMGabrielSEThe effect of oral contraceptives and estrogen replacement therapy on the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a population based studyJ Rheumatol200431220721314760786

- PedersenMJacobsenSKlarlundMEnvironmental risk factors differ between rheumatoid arthritis with and without autoantibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptidesArthritis Res Ther200684R13316872514

- BrennanPBankheadCSilmanASymmonsDOral contraceptives and rheumatoid arthritis: results from a primary care-based incident case-control studySemin Arthritis Rheum19972668178239213380

- PikwerMBergströmUNilssonJAJacobssonLBerglundGTuressonCBreast feeding, but not use of oral contraceptives, is associated with a reduced risk of rheumatoid arthritisAnn Rheum Dis200968452653018477739

- BerglinEKokkonenHEinarsdottirEAgrenARantapää DahlqvistSInfluence of female hormonal factors, in relation to autoantibodies and genetic markers, on the development of rheumatoid arthritis in northern Sweden: a case-control studyScand J Rheumatol201039645446020560812

- VesseyMPVillard-MackintoshLYeatesDOral contraceptives, cigarette smoking and other factors in relation to arthritisContraception19873554574643621942

- HannafordPCKayCRHirschSOral contraceptives and rheumatoid arthritis: new data from the Royal College of General Practitioners’ oral contraception studyAnn Rheum Dis199049107447462241261

- Hernandez-AvilaMLiangMHWillettWCExogenous sex hormones and the risk of rheumatoid arthritisArthritis Rheum19903379479532369431

- KarlsonEWMandlLAHankinsonSEGrodsteinFDo breast-feeding and other reproductive factors influence future risk of rheumatoid arthritis? Results from the Nurses’ Health StudyArthritis Rheum200450113458346715529351

- RodríguezLATolosaLBRuigómezAJohanssonSWallanderMARheumatoid arthritis in UK primary care: incidence and prior morbidityScand J Rheumatol200938317317719117247

- BeydounHAel-AminRMcNealMPerryCArcherDFReproductive history and postmenopausal rheumatoid arthritis among women 60 years or older: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyMenopause201320993093523942247

- AdabPJiangCQRankinEBreastfeeding practice, oral contraceptive use and risk of rheumatoid arthritis among Chinese women: the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort StudyRheumatology (Oxford)201453586086624395920

- WingraveSJReduction in incidence of rheumatoid arthritis associated with oral contraceptives. Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception StudyLancet19781806456957176118

- van ZebenDHazesJMVandenbrouckeJPDijkmansBACatsADiminished incidence of severe rheumatoid arthritis associated with oral contraceptive useArthritis Rheum19903310146214652222531

- PedersenMJacobsenSGarredPStrong combined gene-environment effects in anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide-positive rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide case-control study in DenmarkArthritis Rheum20075651446145317469102

- Hernandez-AvilaMLiangMHWillettWCOral contraceptives, replacement oestrogens and the risk of rheumatoid arthritisBr J Rheumatol198928suppl 1312819344

- SpectorTDRomanESilmanAJA UK case-control study on the effect of parity and the oral contraceptive pill on the development of rheumatoid arthritisBr J Rheumatol198928suppl 1322819345

- Del JuncoDJAnnegersJFCoulamCBLuthraHSThe relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and reproductive functionBr J Rheumatol198928suppl 1332819346

- HazesJMDijkmansBAVandenbrouckeJPDe VriesRRCatsAOral contraceptives and rheumatoid arthritis; further evidence for a protective effect independent of duration of pill useBr J Rheumatol198928suppl 1342819347

- HazesJMSilmanAJBrandRSpectorTDWalkerDJVandenbrouckeJPA case-control study of oral contraceptive use in women with rheumatoid arthritis and their unaffected sistersBr J Rheumatol198928suppl 1352819348

- HannafordPCKayCROral contraceptives and rheumatoid arthritis: new data from the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception StudyBr J Rheumatol198928suppl 1362819349

- LinosAKaklamanisEKontomerkosAVagiopoulosGTjonouAKaklamanisPRheumatoid arthritis and oral contraceptives in the Greek female population: a case-control studyBr J Rheumatol198928suppl 1372819350

- AllebeckPAdamiHOKlareskogLPerssonINon-contraceptive hormones and rheumatoid arthritis: possibilities of using a Swedish population-based cohortBr J Rheumatol198928suppl 138402819351

- KoepsellTDugowsonCVoigtLPreliminary findings from a case-control study of the risk of rheumatoid arthritis in relation to oral contraceptive useBr J Rheumatol198928suppl 1412819353

- GreenlandSQuantitative methods in the review of epidemiologic literatureEpidemiol Rev198791303678409

- DerSimonianRLairdNMeta-analysis in clinical trialsControl Clin Trials1986731771883802833

- HigginsJPThompsonSGQuantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysisStat Med2002211539155812111919

- HigginsJPThompsonSGDeeksJJAltmanDGMeasuring inconsistency in meta-analysesBMJ2003327741455756012958120

- BeggCBMazumdarMOperating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication biasBiometrics1994504108811017786990

- EggerMDavey SmithGSchneiderMMinderCBias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical testBMJ199731571096296349310563

- HamlingJLeePWeitkunatRAmbühlMFacilitating meta-analyses by deriving relative effect and precision estimates for alternative comparisons from a set of estimates presented by exposure level or disease categoryStat Med200827795497017676579

- VandenbrouckeJPOral contraceptives and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: the great transatlantic divide?Scand J Rheumatol Suppl19897931322595337

- VandenbrouckeJPHazesJMDijkmansBACatsAOral contraceptives and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: the great transatlantic divide?Br J Rheumatol198928suppl 1132819340

- EsdaileJMExogenous female hormones and rheumatoid arthritis: a methodological view of the contradictions in the literatureBr J Rheumatol198928suppl 14102819352

- SpectorTDHochbergMCThe protective effect of the oral contraceptive pill on rheumatoid arthritis: an overview of the analytical epidemiological studies using meta-analysisBr J Rheumatol198928suppl 111122819342

- RomieuIHernandez-AvilaMLiangMHOral contraceptives and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of a conflicting literatureBr J Rheumatol198928suppl 113172819343

- SpectorTDHochbergMCThe protective effect of the oral contraceptive pill on rheumatoid arthritis: an overview of the analytic epidemiological studies using meta-analysisJ Clin Epidemiol19904311122112302147033

- LiangMHKarlsonEWFemale hormone therapy and the risk of developing or exacerbating systemic lupus erythematosus or rheumatoid arthritisProc Assoc Am Physicians1996108125288834061

- Pladevall-VilaMDelclosGLVarasCGuyerHBrugués-TarradellasJAnglada-ArisaAControversy of oral contraceptives and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: meta-analysis of conflicting studies and review of conflicting meta-analyses with special emphasis on analysis of heterogeneityAm J Epidemiol199614411148659479

- MasiATAldagJCChattertonRTSex hormones and risks of rheumatoid arthritis and developmental or environmental influencesAnn N Y Acad Sci2006106922323516855149

- VandenbrouckeJPOral contraceptives and rheumatoid arthritisLancet198332283432282296135068

- GandiniSIodiceSKoomenEDi PietroASeraFCainiSHormonal and reproductive factors in relation to melanoma in women: current review and meta-analysisEur J Cancer201147172607261721620689