Abstract

Introduction

Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) is a frequent adverse event that impairs patients’ quality of life. This article evaluates the objective plus subjective efficacy and the safety of methylnaltrexone (MNTX) in OIC patients.

Methods

Randomized controlled trials from a recent systematic review were included. In addition, a PubMed search was conducted for January 2014 to December 21, 2015. We included randomized controlled trials with adult OIC patients, MNTX as study drug, and OIC as primary outcome. Results were categorized in three outcome types: objective outcome measures (eg, time to laxation), patient-reported outcomes (eg, straining), and global burden measures (eg, constipation distress). Dichotomous meta-analyses with risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using RevMan 5.3. Only comparisons between MNTX and placebo were made.

Results

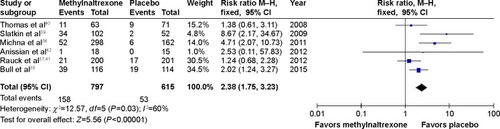

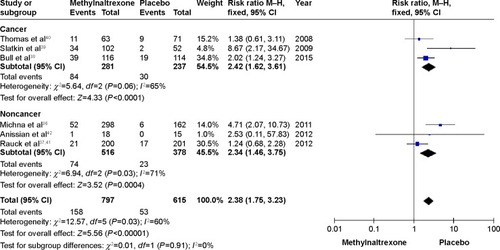

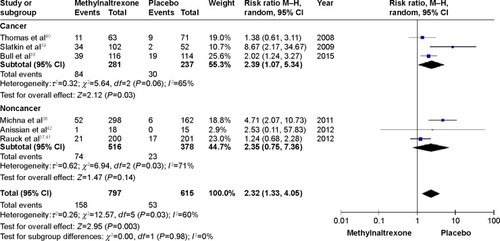

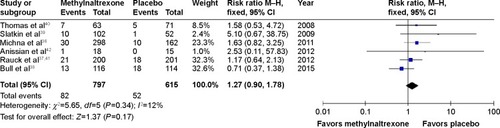

We included seven studies with 1,860 patients. A meta-analysis revealed that patients under MNTX had considerably more rescue-free bowel movement within 4 hours after the first dose (RR 3.74, 95% CI 2.87 to 4.86; five studies, n=938; I2=0). Results of the review indicated that patients under MNTX had a higher stool frequency and needed less time to laxation compared with placebo. Moreover, patients receiving MNTX tended to have better values in patient-reported outcomes and global burden measures. Meta-analyses on safety revealed that patients under MNTX experienced more abdominal pain (RR 2.38, 95% CI 1.75 to 3.23; six studies, n=1,412; I2=60%) but showed a nonsignificant tendency in nausea (RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.78; six studies, n=1,412; I2=12%) and diarrhea (RR 1.45, 95% CI 0.94 to 2.24; five studies, n=1,258; I2=45%). The incidence of MNTX-related serious adverse events was 0.2% (4/1,860).

Conclusion

MNTX has been shown to be effective and safe. Future randomized controlled trials should consequently incorporate objective outcome measures, patient-reported outcomes, and global burden measures, and research the efficacy of MNTX in other populations, for example, patients under opioids after surgical procedures.

Introduction

Opioids are commonly prescribed to treat patients with cancer and noncancer pain.Citation1,Citation2 Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) is a frequent adverse event (AE) of opioid intake and its incidence may vary between 15% and 90%.Citation3–Citation5 It is one of various symptoms such as hard stools, incomplete evacuation, bloating, pain, nausea, and vomiting that belong to a symptom complex known as opioid-induced bowel dysfunction.Citation6–Citation8 Moreover, OIC considerably impedes patients’ quality of life,Citation3,Citation4,Citation9 and work productivity. This may result in additional costs to the health care system as well as society.Citation9,Citation10

Recent works have shown diverse pharmacological treatment opportunities for OIC patients, including methylnaltrexone (MNTX), naloxegol, naloxone, and lubiprostone.Citation6,Citation11,Citation12 However, a meta-analysis was only performed in the systematic review of Ford et alCitation12 who used the individual author’s definitions of “response” as outcome in their meta-analysis and, thus, comparability of the results is affected. In this work, we added relevant information by performing sound meta-analyses with homogeneous outcomes for each analysis. Moreover, we present efficacy of MNTX in the light of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and global burden measures (GBMs) that are defined in the chapter Efficacy of MNTX.

Therefore, our aim is to evaluate the objective plus subjective efficacy and safety of MNTX in patients suffering from OIC.

Pathophysiology and definition

Opioids attach to opioid receptors (eg, μ-opioid receptors) in the brain and the spinal cord, and relieve patients from pain in this way.Citation13 μ-Opioid receptors also appear frequently in the enteric system and play an important role in mediating gastrointestinal effects,Citation14 for example, in reducing bowel tone and contractility. In addition, opioids foster nonpropulsive contractions of the gut which may lead to an increased fluid absorption and harder stools. As a result of this, the sphincter tone increases and impairs rectal evacuation which leads to OIC.Citation15,Citation16

Defining or diagnosing OIC is challenging and only about a third of the clinical trials with interventions for OIC provide an explicit definition.Citation17 In contrast to the Rome III Diagnostic Criteria for functional constipation,Citation18 OIC has a different pathophysiology and is correlated with the onset of opioid intake. Therefore, the following definition has been suggested:

We speak about OIC if the initiation of opioid therapy affects defecation patterns possibly resulting in a reduced spontaneous bowel movement (BM) frequency, the development or worsening of straining, a sense of incomplete evacuation or a harder stool consistency.Citation17

Our definition overlaps in some principal points with the Rome III Diagnostic Criteria (eg, straining, hard stools, sensation of incomplete evacuation). However, our presented definition points to the temporal correlation with opioids and stays on a very individual level (“what individuals would consider as abnormal”) in order to account for intersubjective variations.

Still, when choosing eligibility criteria for a study, pragmatic approaches are usually preferred. Some authors use BM frequency measures as inclusion criteriaCitation19–Citation21 whereas others combine BM frequency measures with PROs.Citation22–Citation27 Moreover, in the field of OIC, most authors tend to define the response to therapy on the basis of BM frequency measures, for example, ≥3 spontaneous BMs per weekCitation12 or BM within 4 hours after the first dose.Citation6

Methylnaltrexone

If lifestyle modifications (eg, increase in dietary fiber or physical activity) and laxatives fail to improve OIC, opioid antagonists are usually recommended as the third step of OIC treatment because they have shown to be effective and address the pathomechanism of OIC.Citation15,Citation28 MNTX, naloxegol, naloxone, and alvimopan aim at antagonizing periphery μ-receptors. These drugs have been studied in recent years.Citation6,Citation7,Citation12,Citation29 Though MNTX was approved for OIC in 2008 by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency,Citation13,Citation30 still, some randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been published in recent years.Citation6,Citation12 In order to consider the latest findings and evaluate objective plus subjective outcomes, we will concentrate on MNTX (or MNTX bromide) in this work. MNTX is a peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonist. It blocks μ-opioid receptors in the gut and inhibits the action of opioids in this way. In contrast to naloxone, MNTX is less able to cross the blood–brain barrier. Therefore, MNTX does not affect opioid analgesia which is of high importance in cancer pain or palliative care patients.Citation13

Methods

In this review, we refer to RCTs evaluating MNTX that were identified in a systematic review of our working group from 2015.Citation6 In addition, PubMed was searched with the following strategy between January 2014 and December 21, 2015: “(methylnaltrexone OR MNTX) AND (opioid induced constipation OR OIC OR bowel dysfunction).” We included RCTs with adult OIC patients (<3 BMs/week), MNTX as study drug, and with OIC as the primary outcome. Full texts, abstracts, and posters from conference proceedings were included as the eligibility criteria were applicable. We categorized the results in three outcome types: objective outcome measures (OOMs; eg, time to laxation), PROs (eg, straining), and GBMs (eg, constipation distress). Meta-analyses were performed if appropriate: Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the Mantel–Haenszel method and the fixed-effect model.Citation31 I2 was used to describe heterogeneity in the meta-analyses. RevMan 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to conduct these dichotomous meta-analyses.

Results

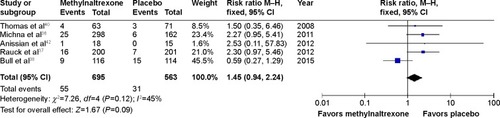

In the previous systematic review,Citation6 six studies were included. Another RCT was retrieved from our search in PubMed. displays an adapted study flow diagram according to the latest recommendations.Citation32 In total, seven studies with 1,860 patients were included in the qualitative and up to six studies with 1,412 patients in the quantitative analyses. A responder analysis of two already included studiesCitation33 and a protocol of an upcoming RCTCitation34 were also identified but subsequently excluded from further evaluation since they did not meet the eligibility criteria. In addition, one studyCitation35 was excluded after reading the full text because the study design was not appropriate (blinded placebo versus open-label MNTX group) and results were part of another RCT.Citation36

Figure 1 Methylnaltrexone randomized controlled trials for opioid-induced constipation treatment: study flow diagram.

MNTX was administered subcutaneously in all studies except in the study by Rauck et al.Citation37 In four RCTs (50%), participants were designated as patients with advanced illness (). The sample sizes ranged from 33Citation26 to 804 patients.Citation37 Five RCTs (71%) included more than 132 patients.Citation36–Citation40 The dropout rates were mostly between 10% and 24%.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

Efficacy of MNTX

Objective outcome measures

OOMs are defined as “measures that could theoretically be collected by an investigator as well as by the patient (eg, bowel movements per week).”Citation17 The primary endpoint of all included studies was an OOM (n=7; 100%). The majority (n=4; 57%) chose rescue-free bowel movement (RFBM) within 4 hours after the first dose as the primaryCitation26,Citation39 or coprimaryCitation36,Citation40 outcome. RFBMs or rescue-free laxation is usually defined as a BM without prior use of any rescue medication or laxatives. “Prior” refers to an arbitrarily defined period of time that can differ between studies, for example, 4 hoursCitation38 or 24 hours.Citation26,Citation36

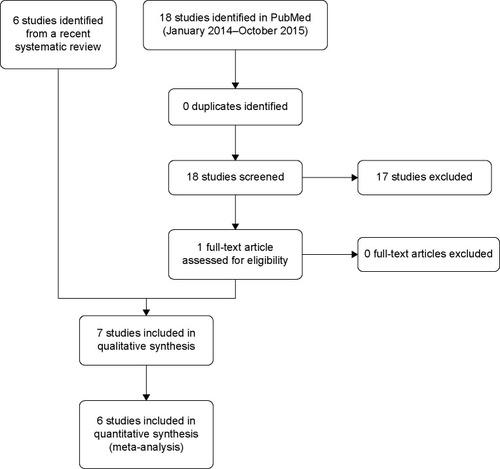

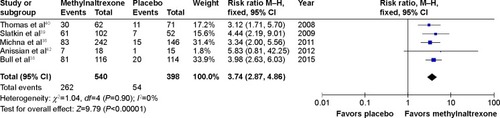

The pooled RR for experiencing one RFBM within 4 hours after the first dose was considerably higher in patients under MNTX (3.74, 95% CI 2.87 to 4.86; P<0.00001) (). The results were consistent across studies (I2=0).

Figure 2 Methylnaltrexone versus placebo: rescue-free bowel movement within 4 hours after the first dose.

The results for three common OOMs are presented in . A greater proportion of patients under MNTX experienced ≥3 RFBMs per week compared with the placebo groups.Citation36,Citation37,Citation40,Citation41 The greatest difference was observed in the study by Thomas et alCitation40 (MNTX: 68%, placebo: 45%, P=0.009). The proportion of patients with an RFBM within 4 hours after the first dose and for all doses or >1 dose was significantly (P<0.05) greater in patients under MNTX in all identified studies (). The median time to the first RFBM was significantly (P<0.05) shorter for patients under MNTX with 0.8 hours as the smallest median.Citation38,Citation39

Table 2 Objective outcome measures assessing OIC

Moreover, Bull et alCitation38 emphasized that no different responses between weight groups () were found. Portenoy et alCitation26 concluded for their dose-ranging study that no apparent dose–response ≥5 mg could be observed which was supported by the results from Slatkin et al.Citation39 Besides, oral MNTX may also be effective; for example, significant differences (P≤0.02) in the 150 mg (34%), 300 mg (41%), and 450 mg (42%) groups for an RFBM were observed within 24 hours compared with placebo (23%).Citation37 However, differences in RFBM frequency measures and RFBM within 4 hours for all doses were only statistically significant for the 300 and 450 mg groups but not for the 150 mg group ().Citation41 The authors concluded that a linear dose–response was existent.

Patient-reported outcomes

PROs are defined as “reports coming directly from patients about how they feel or function in relation to a health condition and its therapy without interpretation by health care professionals or anyone else.”Citation31 In this review, five of seven (71%) included studies reported PROs (). Only one study of the three latest studies (2012–2015) captured PROs.Citation42 The PROs in these five studies were very heterogeneous.Citation26,Citation36,Citation39,Citation40,Citation42 In a study from Anissian et al,Citation42 satisfaction with treatment was 23% (after 4 hours) and 30% (after 7 days) higher in the MNTX group compared with placebo but no trend could be observed in a dose-ranging study by Portenoy et al.Citation26 The Global Clinical Impression of Change identified considerably more MNTX patients than placebo patients under the category “improved” (slightly better, somewhat better, much better) ().Citation39,Citation40 However, no dose–response relationship could be identified for the Global Clinical Impression of Change,Citation39 straining, and sensation of complete evacuation.Citation36 In addition, it can be criticized that difficulty in passing stool and patient satisfaction with study medicationCitation26,Citation40 were presented without any quantitative information.

Table 3 Patient-reported outcomes assessing OIC

Patient-reported GBMs

GBMs were defined as “PROMs that directly quantify the patients’ distress and the impact of OIC on their daily activities or quality of life” in a previous paper.Citation17 Differentiating between PROMs and GBMs is highly important since a PROM (eg, straining) does not automatically imply that the patient feels distressed or that his/her quality of life is affected.

The latest three studies (43%) did not include a GBMCitation37,Citation38,Citation42 in contrast to the studies conducted between 2008 and 2011 ().Citation26,Citation36,Citation39,Citation40 Constipation distress was assessed in three studies and the results indicated an improvement in the MNTX groups.Citation26,Citation39,Citation40 However, the results for constipation distress were presented in a shortened wayCitation26,Citation40 and quantitative data were not provided in one study.Citation40

Table 4 Global burden measures assessing OIC

Moreover, MNTX groups had a larger improvement in the Patient Assessment of Constipation–Quality of Life questionnaire.Citation36 Patients in the MNTX groups (daily and every other day) and in the placebo group improved by 33%, 27%, and 18%, respectively.Citation36 In accordance with the Global Clinical Impression of Change results (), no dose–response relationship could be identified for constipation distress or the Patient Assessment of Constipation–Quality of Life as the differences between the MNTX groups were not statistically or clinically relevant ().Citation36,Citation39

Safety of MNTX

The most frequent AEs during the treatment with peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonists are usually abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea.Citation6 For abdominal pain, the meta-analysis in this review included six studies with a total of 1,412 patients. It revealed that patients under MNTX have a considerably higher risk to experience abdominal pain (RR 2.38, 95% CI 1.75 to 3.23) (). A subgroup analysis showed that this effect was consistent for cancer and noncancer patients (). Interestingly, the effect for noncancer patients disappeared (RR 2.35, 95% CI 0.75 to 7.36) when using the random-effects model for sensitivity analysis but still remained for cancer patients (RR 2.39, 95% CI 1.07 to 5.34) (). In addition, patients treated with MNTX showed only a tendency towards statistical significance concerning nausea and diarrhea when compared with placebo. In a meta-analysis with six studies and 1,412 patients, the risk for experiencing nausea was not significantly higher in patients under MNTX (RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.78; P=0.34) (). The meta-analysis for the risk of experiencing diarrhea included five studies with 1,258 patients (). Though there was a trend in favor of placebo (RR 1.45, 95% CI 0.94 to 2.24), the meta-analysis remained statistically not significant (P=0.12). The study by Bull et alCitation38 questioned the results of the previous studies by showing a contrary effect (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.29), that is, it favors patients under MNTX which leads to an I2 of 45%. In contrast to previous meta-analyses,Citation6 the studies by Bull et alCitation38 and Rauck et alCitation41 were included in the meta-analyses of this review. The consideration of both studies contributed to smaller RRs for abdominal pain (RR −1.62), nausea (RR −0.26), and diarrhea (RR −0.48) compared with the recent meta-analyses by Siemens et alCitation6 and led to a slightly better safety profile than observed in naloxegol for these AEs.

None of the studies reported increased pain or opioid withdrawal symptoms in patients treated with MNTX.Citation26,Citation36–Citation39,Citation42

In all but one study, the route of administration was subcutaneous. Rauck et alCitation41 administered MNTX orally. They concluded that the incidence of AEs was low and that no notable differences in laboratory results or electrocardiogram findings were observed.

The authors of four studies (57%) judged that the observed serious adverse events (SAEs) were not related to MNTX. In total, four MNTX-related SAEs in 1,860 patients (0.2%) were observed. A 50-year-old white female developed extra-systoles in the first day of the double-blind phase that were considered to be related to MNTX.Citation36 Slatkin et alCitation39 reported severe diarrhea, dehydration, and cardiovascular collapse in one patient. Flushing occurred in one patient and delirium in another. All three SAEs were considered to be related to the study drug.

Moreover, no events of gastrointestinal perforation were reported in the included studies but seven cases with gastrointestinal perforation were identified in the Adverse Event Reporting System.Citation43 A possible mechanism for gastrointestinal perforation may be the strong prokinetic effect of MNTX combined with a compromised integrity of the patients’ gastrointestinal tract.Citation43

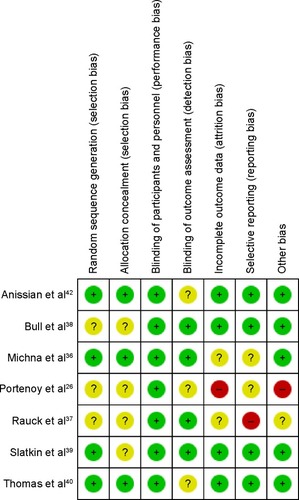

Risk of bias

shows the authors’ judgment about each risk of bias item for the seven included RCTs. All studies had a low risk for performance bias since they were double-blind. The random sequence generation and the allocation concealment were not described in three (43%) and four (57%) of the included studies, respectively. One studyCitation26 was not included in the meta-analyses because of relevant baseline differences (other bias) and a high attrition bias (dropout rate: 29%–50%) that could have affected the effect estimate. For another study,Citation37 only the abstract was available which resulted in an unclear risk of bias for four items. Moreover, there was a high reporting bias because of differences between publication and protocol (NCT01186770) concerning the primary outcome.

Figure 8 Risk of bias summary.

All in all, the risk of bias can be considered as acceptable. However, it should be noted that all studies were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies: five by Valeant Pharmaceuticals International,Citation36,Citation38–Citation40,Citation42 one by Progenics Pharmaceuticals,Citation26 and one by Salix Pharmaceuticals.Citation37

Alternatives

Various reviews investigating drugs for OIC treatment have been identified.Citation6,Citation11,Citation12,Citation28,Citation44,Citation45 They support that MNTX, naloxegol, naloxone, alvimopan, lubiprostone, CB-5945, and prucalopride are effective pharmacological interventions against OIC. However, most works focus on OOMs whereas this review contributes to the awareness of PROs and GBMs for the efficacy evaluation of OIC drugs.

Choosing a drug to target OIC depends on many factors. Still, some authors provide a reasonable concept and suggest that laxatives should be used as the first step in pharmacological treatment. If these are not effective, peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonists may be prescribed in addition.Citation15,Citation28

Limitations

This review refers to studies identified in the systematic review from Siemens et alCitation6 and from an updated search in PubMed (January 2014 and December 2015). The short but precise search strategy was presented in the “Methods” section. However, PubMed was the only database searched.

In contrast to Siemens et al,Citation6 this review comprises all outcome categories: OOMs, PROs, and GBMs. However, not all OOMs of the included studies were evaluated. Rare OOMs (eg, laxation within 24 or 48 hours) were not included and they provide information that is not addressed in this review.

It can be criticized that different populations were included in the meta-analyses. However, the heterogeneity was low except for abdominal pain. Therefore, we performed a subgroup analysis () and sensitivity analysis () only for abdominal pain and compared cancer versus noncancer patients.

The judgment of the key points was based on the effects (mostly RRs), 95% CIs, and number of available RCTs for the different outcomes. The judgment procedure was not systematic. No officially accepted scheme has been used, for example, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.Citation46 However, a risk of bias assessment was performed according to Cochrane standards ().Citation31

Concerning the AEs meta-analyses, only the 450 mg group from the study of Rauck et alCitation37,Citation41 was used but not the 150 and 300 mg groups (–). The lower dose groups tended to have fewer AEs and, thus, our choice represents a conservative approach. In the RCT from Slatkin et al,Citation39 the results for an RFBM within 4 hours hardly differed between both MNTX groups (61.7% vs 58.2% for MNTX 0.15 and 0.3 mg/kg, respectively). Therefore, these groups were combined for the meta-analysis in .

We decided not to perform meta-analysis for the outcome groups BM frequency and time to laxation. These outcomes were assessed in three (43%) and five (71%) of the seven included studies, respectively. However, the outcomes and the quality of data were heterogeneous and prohibited reasonable meta-analysis.

Conclusion

The evaluation of MNTX for OIC treatment is often based on OOMs and less often on PROs and GBMs. MNTX has been shown to be effective for most outcomes assessed in the included RCTs. However, no or only a weak dose–response relationship can be assumed based on the data of the investigated doses. MNTX can be regarded as comparatively safe because hardly any SAEs can be attributed to the drug. However, there is a considerable risk for an increase in abdominal pain, probably related to the intended prokinetic effects of MNTX.

Future RCTs could research the efficacy of MNTX in other populations, for example, in patients under opioids after surgical procedures. Moreover, PROs and GBMs should be an integral part of the efficacy evaluation in order to consider the patients’ perspective of improvement or deterioration of OIC.

Author contributions

WS wrote the article, conducted the meta-analyses, finalized, and approved the draft. GB contributed to the manuscript, critically revised it for methodological and medical issues, and approved the final version. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Mayang Mayang, graduate assistant at the Department of Palliative Care, University Medical Center Freiburg, for her help with data extraction and proofreading. The review was not funded.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BrockCOlesenSSOlesenAEFrøkjaerJBAndresenTDrewesAMOpioid-induced bowel dysfunction: pathophysiology and managementDrugs201272141847186522950533

- BaderSJaroslawskiKBlumHEBeckerGOpioid-induced constipation in advanced illness: safety and efficacy of methylnaltrexone bromideClin Med Insights Oncol2011520121121836816

- BellTJPanchalSJMiaskowskiCBolgeSCMilanovaTWilliamsonRThe prevalence, severity, and impact of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: results of a US and European Patient Survey (PROBE 1)Pain Med2009101354218721170

- PanchalSJMüller-SchwefePWurzelmannJIOpioid-induced bowel dysfunction: prevalence, pathophysiology and burdenInt J Clin Pract20076171181118717488292

- MeuserTPietruckCRadbruchLStutePLehmannKAGrondSSymptoms during cancer pain treatment following WHO-guidelines: a longitudinal follow-up study of symptom prevalence, severity and etiologyPain200193324725711514084

- SiemensWGaertnerJBeckerGAdvances in pharmacotherapy for opioid-induced constipation – a systematic reviewExpert Opin Pharmacother201516451553225539282

- PoulsenJLBrockCOlesenAENilssonMDrewesAMClinical potential of naloxegol in the management of opioid-induced bowel dysfunctionClin Exp Gastroenterol2014734535825278772

- BeckerGBlumHENovel opioid antagonists for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction and postoperative ileusLancet200937396701198120619217656

- CoyneKLoCasaleRDattoCSextonCYeomansKTackJOpioid-induced constipation in patients with chronic noncancer pain in the USA, Canada, Germany, and the UK: descriptive analysis of baseline patient-reported outcomes and retrospective chart reviewClinicoecon Outcomes Res201424626928124904217

- HjalteFBerggrenABergendahlHHjortsbergCThe direct and indirect costs of opioid-induced constipationJ Pain Symptom Manage201040569670320727708

- LeppertWEmerging therapies for patients with symptoms of opioid-induced bowel dysfunctionDrug Des Devel Ther2015922152231

- FordACBrennerDMSchoenfeldPSEfficacy of pharmacological therapies for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation: systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Gastroenterol2013108101566157423752879

- European Medicines Agency Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/000870/human_med_001022.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124Accessed October 28, 2015

- HolzerPOpioids and opioid receptors in the enteric nervous system: from a problem in opioid analgesia to a possible new prokinetic therapy in humansNeurosci Lett20043611–319219515135926

- KumarLBarkerCEmmanuelAOpioid-induced constipation: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and managementGastroenterol Res Pract2014201414173724883055

- BenyaminRTrescotAMDattaSOpioid complications and side effectsPain Physician2008112 SupplS105S12018443635

- GaertnerJSiemensWCamilleriMDefinitions and outcome measures of clinical trials regarding opioid-induced constipation: a systematic reviewJ Clin Gastroenterol201549191625356996

- LongstrethGFThompsonWGCheyWDHoughtonLAMearinFSpillerRCFunctional bowel disordersGastroenterology200613051480149116678561

- JoswickTMareyaSMLichtlenPWoldegeorgisFUenoRTime to onset of lubiprostone treatment effect in chronic non-cancer pain patients with opioid-induced constipation: Data from two phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialsGastroenterology20131445 Supplement 1540

- LichtlenPJoswickTWoldegeorgisFUenoRLubiprostone is well tolerated in chronic non-cancer pain patients with opioid-induced constipation in three phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialsGastroenterology20131445 Supplement 1916

- MareyaSMLichtlenPWoldegeorgisFJoswickTUenoRLubiprostone improves complete spontaneous bowel movement frequency in chronic non-cancer pain patients with opioid-induced constipationGastroenterology20131445 Supplement 1539540

- WirzSNadstawekJElsenCJunkerUWartenbergHCLaxative management in ambulatory cancer patients on opioid therapy: a prospective, open-label investigation of polyethylene glycol, sodium picosulphate and lactuloseEur J Cancer Care (Engl)201221113114021880080

- IrvingGPenzesJRamjattanBA randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (Study SB-767905/013) of alvimopan for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction in patients with non-cancer painJ Pain201112217518421292168

- JansenJPLorchDLanganJA randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (Study SB-767905/012) of alvimopan for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction in patients with non-cancer painJ Pain201112218519321292169

- WirzSWittmannMSchenkMGastrointestinal symptoms under opioid therapy: a prospective comparison of oral sustained-release hydromorphone, transdermal fentanyl, and transdermal buprenorphineEur J Pain200913773774318977159

- PortenoyRKThomasJMoehlBMLSubcutaneous methylnaltrexone for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with advanced illness: a double-blind, randomized, parallel group, dose-ranging studyJ Pain Symptom Manage200835545846818440447

- WirzSWartenbergHCNadstawekJLess nausea, emesis, and constipation comparing hydromorphone and morphine? A prospective open-labeled investigation on cancer painSupport Care Cancer2008169999100918095008

- PrichardDBharuchaAManagement of opioid-induced constipation for people in palliative careInt J Palliat Nurs201521627228026126675

- BaderSDürkTBeckerGMethylnaltrexone for the treatment of opioid-induced constipationExpert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol201371132623265145

- U.S. Food and Drug AdministrationFDA Approves Relistor for Opioid-Induced Constipation Available from: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2008/ucm116885.htmAccessed January 15, 2016

- HigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.org/Accessed October 28, 2013

- StovoldEBeecherDFoxleeRNoel-StorrAStudy flow diagrams in Cochrane systematic review updates: an adapted PRISMA flow diagramSyst Rev201435424886533

- NalamachuSRPergolizziJTaylorREfficacy and tolerability of subcutaneous methylnaltrexone in patients with advanced illness and opioid-Induced constipation: a responder analysis of 2 randomized, placebo-controlled trialsPain Pract201515656457124815199

- NeefjesECvan der VorstMJBoddaertMSClinical evaluation of the efficacy of methylnaltrexone in resolving constipation induced by different opioid subtypes combined with laboratory analysis of immunomodulatory and antiangiogenic effects of methylnaltrexoneBMC Palliat Care2014134225165428

- ViscusiERBarrettACPatersonCForbesWPEfficacy and safety of methylnaltrexone for opioid-induced constipation in patients with chronic noncancer pain: a placebo crossover analysisReg Anesth Pain Med201641939826650429

- MichnaEBlonskyERSchulmanSSubcutaneous methylnaltrexone for treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with chronic, nonmalignant pain: a randomized controlled studyJ Pain201112555456221429809

- RauckRLPeppinJIsraelROral methylnaltrexone for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with noncancer painGastroenterology2012142suppl 1160

- BullJWellmanCVIsraelRJBarrettACPatersonCForbesWPFixed-dose subcutaneous methylnaltrexone in patients with advanced illness and opioid-induced constipation: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled study and open-label extensionJ Palliat Med201518759360025973526

- SlatkinNThomasJLipmanAGMethylnaltrexone for treatment of opioid-induced constipation in advanced illness patientsJ Support Oncol200971394619278178

- ThomasJKarverSCooneyGAMethylnaltrexone for opioid-induced constipation in advanced illnessN Engl J Med2008358222332234318509120

- RauckRLPeppinJIsraelROral methylnaltrexone for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with chronic non-cancer painDigestive Disease Week (DDW)519–222012San Diego, CA Available from: http://www.medscape.com/viewcollection/32463Accessed October 28, 2015

- AnissianLSchwartzHWVincentKSubcutaneous methylnaltrexone for treatment of acute opioid-induced constipation: phase 2 study in rehabilitation after orthopedic surgeryJ Hosp Med201272677221998076

- MackeyACGreenLGreenePAviganMMethylnaltrexone and gastrointestinal perforationJ Pain Symptom Manage2010401e1e320619194

- SantucciGBattistaVMethylnaltrexone for opioid-induced constipation in patients at the end of lifeInt J Palliat Nurs201521416216425901587

- CorsettiMTackJNaloxegol: the first orally administered, peripherally acting, mu opioid receptor antagonist, approved for the treatment of opioid-induced constipationDrugs Today (Barc)201551847948926380386

- BalshemHHelfandMSchünemannHJGrading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (short GRADE)J Clin Epidemiol201164440140621208779