Abstract

The antithrombotic action of aspirin has long been recognized. Aspirin inhibits platelet function through irreversible inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) activity. Until recently, aspirin has been mainly used for primary and secondary prevention of arterial antithrombotic events. The aim of this study was to review the literature with regard to the various mechanisms of the newly discovered effects of aspirin in the prevention of the initiation and development of venous thrombosis. For this purpose, we used relevant data from the latest numerous scientific studies, including review articles, original research articles, double-blinded randomized controlled trials, a prospective combined analysis, a meta-analysis of randomized trials, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, and multicenter studies. Aspirin is used in the prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE), especially the prevention of recurrent VTE in patients with unprovoked VTE who were treated with vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) or with non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs). Numerous studies have shown that aspirin reduces the rate of recurrent VTE in patients, following cessation of VKAs or NOACs. Furthermore, low doses of aspirin are suitable for long-term therapy in patients recovering from orthopedic or other surgeries. Aspirin is indicated for the primary and secondary prevention as well as the treatment of cardiovascular diseases, including acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, acute ischemic stroke, and transient ischemic attack (especially in atrial fibrillation or mechanical heart valves). Aspirin can prevent or treat recurrent unprovoked VTEs as well as VTEs occurring after various surgeries or in patients with malignant disease. Recent trials have suggested that the long-term use of low-dose aspirin is effective not only in the prevention and treatment of arterial thrombosis but also in the prevention and treatment of VTE. Compared with VKAs and NOACs, aspirin has a reduced risk of bleeding.

Introduction

The incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is common, affecting approximately one person per 1,000 in the general population.Citation1 Additionally, VTE is estimated to be the third most common cardiovascular disease after coronary heart disease and stroke,Citation2 and VTE is often fatal. The prevention and treatment of VTE pose a major medical challenge. Antithrombotic substances have decreased the rates of venous and arterial thrombotic phenomena as well as their consequences.Citation3,Citation4 Examples of these substances include inhibitors of platelet aggregation and anticoagulant drugs. Orally active anticoagulants include vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOACs)Citation5–Citation10 that do not oppose vitamin K. Parenteral anticoagulants include unfractionated heparin and low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs),Citation11,Citation12 which directly or indirectly exert their anticoagulant effects through one mechanism. Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) is an antiaggregant and anticoagulant via a number of mechanisms.Citation13 The aim of this paper is to summarize new insights into the mechanisms of action of aspirin in the prevention of arterial and venous thrombosis. Arterial thrombosis can manifest as a heart attack or a stroke. Venous thrombosis can complicate orthopedic surgery or the course of malignant disease. In this manuscript, the role of aspirin in the prevention and treatment of primary and secondary VTE is reviewed.

Aspirin

Aspirin was discovered by Felix Hoffmann, a chemist in the pharmaceutical laboratory of the German manufacturer (Friedrich Bayer & Co., Elberfeld, Germany). Hoffmann prepared the first pure sample of acetylsalicylic acid in August 1897, and it was marketed and registered under the trademark name aspirin in 1899.Citation14 After oral administration, aspirin is rapidly absorbed from the stomach and upper small intestine, and the oral bioavailability of regular aspirin tablets is 40%–50% over a wide range of doses. The peak plasma level occurs 30–40 minutes after ingestion of ordinary aspirin tablets and 3–4 hours after ingestion of enteric-coated tablets. The inhibition of platelet function is dependent on the form of aspirin.Citation15,Citation16 Aspirin is widely used for the treatment of fever, migraines, and other conditions, including pain associated with inoperable cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatic fever, and acute tonsillitis.Citation17

Clinical indications of aspirin

Currently, the clinical indications for the use of aspirin are as follows: primary prevention of cardiovascular events; prevention and treatment of primary and secondary stroke, as well as atrial fibrillation (AF) (to prevent stroke); treatment of acute ischemic stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA); and prevention of secondary stroke/TIA.Citation18 However, according to Sato et al, a low dose of aspirin (150–200 mg per day) is not effective or safe in the prevention of ischemic stroke with AF.Citation19 Other indications for the use of aspirin include acute coronary syndrome, peripheral artery disease, anterior myocardial infarction (MI) with left ventricular (LV) thrombus, anterior MI with high risk of LV thrombus, and mechanical heart valve.Citation18 Aspirin is increasingly being applied to the prevention and treatment of thromboembolic phenomena, such as primary and secondary venous thrombosis, especially after major orthopedic surgery and other operations.Citation20

Contraindications of aspirin

The contraindications of aspirin are classified as absolute or relative. The absolute contraindications include active peptic ulcer, aspirin allergy, aspirin intolerance, hereditary bleeding disorders, thrombocytopenia, history of recent gastrointestinal bleeding, recent history of intracranial bleeding, renal impairment, and severe liver disease. The relative contraindications of aspirin include age younger than 21 years (increased risk of Reye syndrome), concurrent use of anticoagulation therapy, concurrent use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and poorly controlled hypertension (risk of intracranial bleeding).Citation21

Mechanisms of action of aspirin

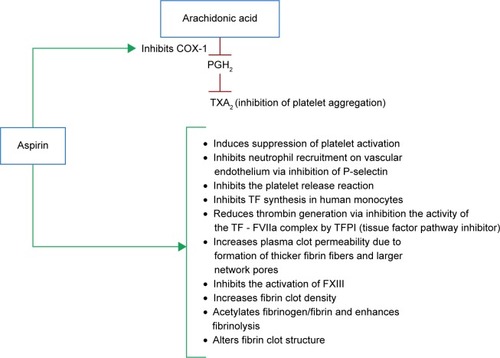

Acetylsalicylic acid acts as an acetylating agent. Thus, aspirin irreversibly inactivates cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and suppresses the generation of prostaglandin H2 (a precursor of thromboxane A2). Aspirin achieves this effect through its acetyl group, which becomes covalently attached to Ser529 of the active site of the COX-1 enzyme.Citation22 Aspirin interacts with the amino acid Arg120 and consequently blocks the access of arachidonic acid to the hydrophobic channel to Tyr385 at the catalytic site. Thus, aspirin inhibits the generation of prostaglandin H2.Citation15 According to Undas et al, the antithrombotic effects of aspirin also involve the acetylation of other proteins of blood coagulation, including fibrinogen. Therefore, aspirin promotes fibrinolysis.Citation13 Although aspirin can inhibit COX-2 by acetylating Ser516, this reaction is approximately 170-fold slower than the reaction with COX-1.Citation14 Lei et al reported the reaction with COX-2 to be ten to 100 times slower than the reaction with COX-1.Citation23 Aspirin produces an irreversible defect in thromboxane synthesis for the lifetime of affected platelets (8–10 days).Citation24 The effect of aspirin on platelets is primarily related to downregulation of dense granule release. Alpha granule secretion is not impeded by COX-1 blockade in platelets that are stimulated by adenosine diphosphate (ADP) or thrombin.Citation25 Only 10% of the platelet pool is replenished daily. Therefore, administration of aspirin in low doses can fully inhibit COX-1 (causing long lasting deffect), on repeat daily dosing, despite the fact that the half-life of aspirin is 15 to 20 minutes due to rapid presystemic hydrolysis that is catalyzed by esterase.Citation15,Citation26

Recent studies have explained the role and mechanisms of action of aspirin in the prevention of VTE. Aspirin-mediated prevention involves the inhibition of platelets. The binding of platelets and recruitment of neutrophils to the vascular endothelium is an early step in the development of deep vein thrombosis.Citation27 Because the recruitment and rolling of leukocytes, as well as their initial attachment to vascular endothelium, is dependent on a glycoprotein called P-selectin, the inhibition of P-selectin is associated with a reduced weight of mice subjected to thrombus induced by ligation of the inferior vena cava.Citation28 Additionally, platelet inactivation by aspirin results in the inhibition of the release of the following platelet-associated substances into the venous circulation: platelet factors V and XIII, fibrinogen, platelet factors 3 and 4, thrombospondin, von Willebrand factor (vWF), calcium ions, serotonin, and other substances that favor the development of venous thrombosis. Enzymatic complexes (especially prothrombinase complex) form on the surfaces of activated platelets, and a large number of receptors are available for these complexes.Citation13 Aspirin also prevents thrombin formation that is catalyzed by the calcium ion-dependent complex of tissue factor (TF) and activated factor VII (FVIIa). The inhibition of this complex by aspirin promotes the inhibition of factors IX and X. The formation of the prothrombinase complex and thrombin is subsequently inhibited.Citation29 Thrombin is the serine protease that converts fibrinogen to fibrin, which polymerizes to form a thrombus. The inhibition of thrombin production by aspirin can be explained by two additional mechanisms, as follows: increased secretion of TF pathway inhibitor (TFPI) as well as the acetylation of prothrombin and several membrane components.Citation30 Some authors have proposed that aspirin impacts the quality of fibrin within the thrombus. Properties of fibrin are dependent on the structural characteristics at the molecular level and at the level of individual fibers. The properties also depend on the arrangements of the three-dimensional networks.Citation31 Acetylation of fibrinogen is an important mechanism of action of aspirin. Acetylation increases the porosity of the fibrin network and therefore increases the rate of fibrinolysis.Citation32 The antithrombotic effect of high doses of aspirin potentially stems from reduced synthesis of coagulation factors in the liver, and this mechanism resembles those of VKAs. Furthermore, a reduction in thrombin levels reduces FXIII activation.Citation33,Citation34 The overall mechanisms of aspirin in the prevention and treatment of arterial and VTE are presented in .

The role of aspirin in the prevention of arterial thromboembolic events

Until recently, aspirin has been considered to be a drug that prevents arterial thrombosis through COX-1 inhibition.Citation35 One study has confirmed that aspirin therapy is suitable for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events,Citation36 but few clinical trials studying the efficacy of aspirin in the primary prevention of those events have been conducted. However, current guidelines define a role for aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular events.Citation37 The earliest events in thrombus formation are platelet adhesion followed by aggregation, platelet activation, and granule release. Except for platelet adhesion, all of these platelet functions are inhibited by aspirin. Thus, the drug reduces the risks of arterial thrombotic events.Citation38 In a large number of atherosclerotic diseases (such as coronary, cerebrovascular, and peripheral arterial disease), aspirin and other antiplatelet drugs are the mainstays of treatment.Citation39 According to six primary prevention trials performed by the Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration, administration of aspirin leads to a 12% reduction in serious vascular events.Citation40

Aspirin reduces nonfatal MIs by 20% but does not decrease ischemic strokes.Citation40 In 16 secondary prevention trials, the same authors reported that aspirin therapy produces absolute reductions in vascular events, strokes, and coronary events, with percentages of 6.7% vs 8.2% per year (P<0.0001), 2.08% vs 2.54% per year (P=0.002), and 4.3% vs 5.3% per year (P<0.0001), respectively.Citation40 In their meta-analysis of nine trials involving 102,621 patients (52,145 in the aspirin group and 50,476 in the placebo/control group), Berger et al found that aspirin is associated with a reduction in major cardiovascular events with a risk ratio of 0.90 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.85–0.96, P<0.001). However, these authors did not observe significant reductions of MI, stroke, ischemic stroke, or all-cause mortality.Citation41 Despite significant primary reductions in the rates of nonfatal MI (odds ratio [OR] 0.80; 95% CI: 0.67–0.96), Seshasai et al found that aspirin prophylaxis does not reduce either cardiovascular death or cancer mortality in patients without prior cardiovascular disease.Citation42

In general, aspirin should be administered once daily. The daily doses are based on international guidelines that depend on various clinical indications. According to the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), doses of aspirin in the range of 50–160 mg have value in the prevention and treatment of almost all cardiovascular diseases. In cases of mechanical heart valves, the recommended daily doses are 50–100 mg.Citation43 For the primary prevention of cardiovascular events, anterior MI with LV thrombus, high risk of LV thrombus, acute coronary syndrome, and secondary stroke/TIA prevention, aspirin should be administered at daily doses of 75–100 mg.Citation44 Higher doses of aspirin (75–325 mg) are needed to prevent stroke in AF and in peripheral artery disease.Citation45,Citation46 For the treatment of acute ischemic stroke/TIA, aspirin should be started at a daily dose of 160–325 mg within 48 hours.Citation47

The role of aspirin in the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism

Aspirin was initially appreciated in the prevention of arterial thrombosis. In 1977, aspirin (600 mg twice daily) was shown to reduce the risk of venous thrombosis in patients recovering from hip arthroplasty.Citation48 Anderson et al examined the hip and knee registry for the period of 1996–2001, and they found that 4%–7% of patients received aspirin exclusively for thromboprophylaxis following primary total hip replacement, or total knee arthroplasty.Citation49 Hovens et al summarized the evidence for the efficacy of aspirin in the prevention and treatment of VTE, and they concluded that further studies should examine the value of aspirin after a first unprovoked VTE.Citation50 Two randomized controlled trials (the Warfarin and Aspirin [WARFASA] and the Aspirin to Prevent Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism [ASPIRE]) demonstrated that aspirin is suitable for long-term application to reduce the risk of recurrent VTE. The WARFASA trial is a multicenter, randomized, double-blinded study that included 403 patients previously treated with VKAs. Recurrent VTE occurred in 28 of the 205 patients treated with aspirin and in 43 of the 197 patients in the placebo group (2 weeks after withdrawal of VKAs), with percentages of 6.6% vs 11.2% per year, respectively (hazard ratio [HR] 0.58; 95% CI: 0.36–0.93, P=0.02).Citation51 In the ASPIRE trial, 822 patients were treated with aspirin or placebo. As was the case in the WARFASA study, patients in the ASPIRE trial were previously treated with anticoagulants for 1.5–24 months due to spontaneous VTE or pulmonary embolism. The rate of recurrent VTE in patients treated with aspirin was 4.8% per year, and a rate of 6.5% per year occurred in the placebo group (HR 0.47; 95% CI: 0.52–1.05). No significant difference in VTE incidence was noted between the aspirin and placebo groups (P=0.09).Citation52 ČulićCitation53 and ParaskevasCitation54 expressed concerns with regard to the impacts of sex and statins on the outcomes of the ASPIRE and WARFASA trials. The concerns are based on sex differences in platelet sensitivity to low doses of aspirin.Citation55 Statins also influence the effect of aspirin on VTE.Citation56 Simes et al reported that men have an increased risk of recurrent VTE compared with women. The risk also increases with advancing age.Citation57 In the INSPIRE analysis, the same authors estimated the effect of aspirin treatment on VTE before and after adjustment of the baseline characteristics of the patients with similar HRs of 0.68 (95% CI: 0.51–0.90, P=0.008) and 0.65 (95% CI: 0.49–0.86, P=0.003), respectively. These authors also analyzed the efficacy of aspirin in reducing the rate of recurrent DVT without symptomatic pulmonary embolism, and they found that aspirin decreases the rate of recurrent DVT by 34% without significantly increasing the risk of bleeding.Citation57 Sobieraj et al performed a meta-analysis of ten trials (n=11,079), and they found that various novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) (apixaban at doses of 2.5 and 5 mg as well as dabigatran and rivaroxaban) as well as idraparinux and VKAs each significantly reduced the risk of VTE recurrence with respect to placebo. All of the mentioned drugs, with the exception of idraparinux, more effectively prevented VTE than aspirin. However, the risk of bleeding was reduced in patients treated with aspirin.Citation58 In a study on the extended (28-day regimen) use of aspirin prophylaxis to combat VTE after total hip arthroplasty, Anderson et al found that after administration of dalteparin prophylaxis for 10 days, aspirin treatment was not inferior (P<0.001) or superior (P=0.22) to continued dalteparin treatment for preventing VTE.Citation59 According to Prandoni et al, low doses of aspirin offer a safe and cost-effective option for the long-term prevention of recurrent events in patients with unprovoked VTE, especially in patients without symptomatic atherosclerotic lesions.Citation60 Low-dose aspirin reduces the rates of recurrent VTE, but aspirin has not been previously compared with other anticoagulants. In the EINSTEIN CHOICE study, Weitz et al will compare rivaroxaban (10 and 20 mg) with aspirin (100 mg daily) for the prevention of symptomatic recurrent VTE. The study will include 2,850 patients from 230 sites of 32 countries over a 27-month period. According to the EINSTEIN CHOICE Investigators, the trial will provide new insights into the optimal strategies for the extended treatment of VTE.Citation61 For the prevention of VTE and recurrent VTE as well as for prophylaxis against venous thromboembolic events after orthopedic surgery (long-term or extended VTE prophylaxis [VTEP]), aspirin is typically administered at the low, once-daily dose of 100 mg.Citation51,Citation52 The recent studies on prevention of recurrent unprovoked VTE by aspirin are presented in .

Table 1 Recent studies on prevention of recurrent unprovoked VTE by aspirin

The role of aspirin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism in orthopedic surgery

VTE is an important and common complication after major orthopedic surgery. Bozic et al analyzed clinical data from 93,840 patients who underwent primary TKA during a 24-month period. Of those patients, 51,923 (55%) received warfarin and 37,198 (40%) were treated with injectable agents. However, only 4,719 (5%) of these patients received aspirin. The patients who received aspirin for VTEP had lower risk for thromboembolism compared with patients administered warfarin, but the risk of VTE with aspirin as the preventive measure was similar to the risk when injectable VTEP was the measure. These results suggest that aspirin may be effective for VTEP for certain TKA patients when it is used in accordance with other clinical care protocols.Citation62 Jiang et al compared the efficacies of aspirin (group A) and LMWHs followed by rivaroxaban (group B) in combination with mechanical postoperative measures in the prevention VTE after TKA, and they did not report any significant differences. In group A, ten of 60 patients (16.7%) suffered a DVT (95% CI: 7.3–26.1), and in group B (LMWHs/rivaroxaban), eleven of 60 patients (8.3%) suffered a DVT (95% CI: 8.5–27.8) (P=0.500).Citation63 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the ACCP offer guidelines for the use of aspirin for the prophylaxis of VTE events in patients recovering from orthopedic surgery. Consistent with the guidelines, many surgeons select aspirin for VTEP, especially in patients undergoing TKA.Citation64 According to Knesek et al, the most recent AAOS and ACCP guidelines allow considerable autonomy in the choice of prophylactic agents (VKAs, NOACS, and LMWHs) for thromboembolic prophylaxis following total joint arthroplasty.Citation65 In view of independent observational studies that identified minimal difference between LMWHs and aspirin, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines may be overly reliant on assumptions and may warrant revision.Citation66

Adverse effects of aspirin

Increased bleeding is the most frequent and important side effect of aspirin. Gastrointestinal bleeding is reported in approximately 3% of elderly patients treated with aspirin.Citation67 To reduce the incidence of this adverse effect of aspirin, it is reasonable to prescribe low doses of enteric-coated aspirin. The risk of major gastrointestinal events is increased by 30%, to 70% over the overall baseline risk of 0.7 per 1,000 per year that is observed with low- or standard-dose aspirin was compared with enteric-coated aspirin (to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding).Citation67 Although hemorrhagic strokes are rare, they are the most serious side effect and are potentially fatal. It is estimated that hemorrhagic strokes occur at a rate of 0.03% per year in aspirin users.Citation40 Additionally, hematologic side effects, such as hypoprothrombinemia,Citation68 thrombocytopenia,Citation69 and pancytopenia, have been rarely reported.Citation70 Other side effects of aspirin include renal, dermatologic, hepatic, oncologic, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and respiratory problems. Hypersensitivity to aspirin can also occur.

Conclusion

Many recent randomized controlled trials have indicated that aspirin achieves its antithrombotic effects through more mechanisms than previously realized. Aspirin is a promising drug for the prevention of recurrent unprovoked VTE, and its long-term use does not carry a great risk of major bleeding. Other advantages of aspirin include its low cost, once-daily application, and lack of need for dose monitoring.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SilversteinMDHeitJAMohrDNPettersonTMO’FallonWMMeltonLJ3rdTrends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25-year population-based studyArch Intern Med199815865855939521222

- GoldhaberSZPulmonary embolism thrombolysis: a clarion call for international collaborationJ Am Coll Cardiol19921922462471732348

- PatronoCRoccaBAspirin, 110 years laterJ Thromb Haemost20097Suppl 125826119630812

- Gómez-OutesASuárez-GeaMLCalvo-RojasGDiscovery of anticoagulant drugs: a historical perspectiveCurr Drug Discov Technol2012928310421838662

- FerlundPStenfloJRoepstorffPThomsenJVitamin K and the biosynthesis of prothrombin. V. Gamma-carboxyglutamic acids, the vitamin K- dependent structures in prothrombinJ Biol Chem1975250156125613350323

- HirshJDalenJEAndersonDROral anticoagulants: mechanism of action, clinical effectiveness, and optimal therapeutic rangeChest1998114445S469S9822057

- KlauserWDütschMPractical management of new oral anticoagulants after total hip or total knee arthroplastyMusculoskelet Surg201397318919724249360

- ConnollySJEzekowitzMDYusufSRE-LY Steering Committee and InvestigatorsDabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med2009361121139115119717844

- da SilvaRMNovel oral anticoagulants in non-valvular atrial fibrillationCardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem20141213825470147

- MekajYHMekajAYDuciSBMiftariEINew oral anticoagulants: their advantages and disadvantages compared with vitamin K antagonists in the prevention and treatment of patients with thromboembolic eventsTher Clin Risk Manag20151196797726150723

- HirshJAnandSSHalperinJLFusterVMechanism of action and pharmacology of unfractionated heparinArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol20012171094109611451734

- WeitzJILow-molecular-weight heparinsN Engl J Med199733710668698

- UndasABrummel-ZiedinsKMannKGWhy does aspirin decrease the risk of venous thromboembolism? On old and novel antithrombotic effects of acetyl salicylic acidJ Thromb Haemost2014121111761187

- SneaderWThe discovery of aspirin: a reappraisalBMJ200032172761591159411124191

- PatronoCCollerBFitzGeraldFAHirshJRothGPlatelet-active drugs: the relationship among dose, effectiveness, and side effects: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic TherapyChest20041263 Suppl234S264S15383474

- PedersenAKFitzGeraldGADose-related kinetics of aspirin. Presystemic acetylation of platelet cyclooxygenaseN Engl J Med198431119120612116436696

- WilthauerJWohlgemutJUber aspirine (acetylsalicylic acid)Ther Mh (Halbmh)189913276 German

- EikelboomJWHirshJSpencerFABaglinTPWeitzJIAntiplatelet drugs: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice GuidelinesChest20121412 Supple89Se119S22315278

- SatoHIshikawaKKitabatakeAJapan Atrial Fibrillation Stroke Trial GroupLow-dose aspirin for prevention of stroke in low-risk patients with atrial fibrillation: Japan Atrial Fibrillation Stroke TrialStroke20063744745116385088

- No authors listedPrevention of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis with low dose aspirin: Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trialLancet200035592121295130210776741

- MiserWFAppropriate aspirin use for primary prevention of cardiovascular diseaseAm Fam Physician201183121380138621671538

- TóthLMuszbekLKomáromiIMechanism of the irreversible inhibition of human cyclooxygenase-1 by aspirin as predicted by QM/MM calculationsJ Mol Graph Model2013409910923384979

- LeiJZhouYXieDZhangYMechanistic insights into a classic wonder drug – aspirinJ Am Chem Soc20151371707325514511

- MareeAOFitzgeraldDJVariable platelet response to aspirin and clopidogrel in atherothrombotic diseaseCirculation2007115162196220717452618

- RinderCSStudentLABonanJLRinderHMSmithBRAspirin does not inhibit adenosine diphosphate-induced platelet alpha-granule releaseBlood19938225055127687162

- PatrignaniPFilabozziPPatronoCSelective cumulative inhibition of platelet thromboxane production by low-dose aspirin in healthy subjectsJ Clin Invest1982696136613727045161

- FuchsTABrillAWagnerDDNeutrophil extracellular trap (NET) impact on deep vein thrombosisArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol20123281777178322652600

- MeierTRMyersDDJrWrobleskiSKProphylactic P-selectin inhibition with PSI-421 promotes resolution of venous thrombosis without anticoagulationThromb Haemost200899234335118278184

- ButenasSOrfeoTMannKGTissue factor in coagulation: Which? Where? When?Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol200929121989199619592470

- SzczeklikAKrzanowskiMGóraPRadwanJAntiplatelet drugs and generation of thrombin in clotting bloodBlood1992808200620111391958

- BrownAELitvinovRIDischerDEPurohitPKWeiselJWMultiscale mechanics of fibrin polymer: gel stretching with protein unfolding and loss of waterScience2009325594174174419661428

- LordSTMolecular mechanisms affecting fibrin structure and stabilityArterioscler Thomb Vasc Biol2011313494499

- LoewDVinazzerHDose-dependent influence of acetylsalicylic acid on platelet functions and plasmatic coagulation factorsHaemostasis1976542392491002006

- UndasASydorWJBrummelKMusialJMannKGSzczeklikAAspirin alters the cardioprotective effects of the factor XIII Val34Leu polymorphismCirculation20031071172012515735

- WarkentinTEAspirin for dual prevention of venous and arterial thrombosisN Engl J Med2012367212039204123121404

- YasueHOgawaHTanakaHEffects of aspirin and trapidil on cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. Japanese Antiplatelets Myocardial Infarction Study (JAMIS) InvestigatorsAm J Cardiol19998391308131310235086

- IttamanSVVanWormerJJRezkallaSHThe role of aspirin in the prevention of cardiovascular diseaseClin Med Res2014123–414715424573704

- HoLLBrightonTWarfarin, antiplatelet drugs and their interactionsAust Prescr2002258185

- MorimotoTNakayamaMSaitoYOgawaHAspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic disease in JapanJ Atheroscler Thromb200714415916617726295

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) CollaborationBaigentCBlackwellLAspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trialsLancet200937396781849186019482214

- BergerJSLalaAKrantzMJBakerGSHiattWRAspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients without clinical cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trialsAm Heart J20111621115124.e221742097

- SeshasaiSRWijesuriyaSSivakumaranREffect of aspirin on vascular and nonvascular outcomes: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsArch Intern Med2012172320921622231610

- WhitlockRPSunJCFremesSERubensFDTeohKHAmerican College of Chest PhysiciansAntithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for valvular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice GuidelinesChest20121412 Supple576Se600S22315272

- VandvikPOLincoffAMGoreJMAmerican College of Chest PhysiciansPrimary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice GuidelinesChest20121412 Supple637Se668S22315274

- YouJJSingerDEHowardPAAmerican College of Chest PhysiciansAntithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice GuidelinesChest20121412 Supple531Se575S22315271

- SmithSCJrBenjaminEJBonowROWorld Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses AssociationAHA/ACCF Secondary Prevention and Risk Reduction Therapy for patients with Coronary and other Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology FoundationCirculation2011124222458247322052934

- LansbergMGO’DonnellMJKhatriPAmerican College of Chest PhysiciansAntithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic Therapy And Prevention Of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice GuidelinesChest20121412 Supple601Se636S22315273

- HarrisWHSalzmanEWAthanasoulisCAWaltmanACDeSanctisRWAspirin prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism after total hip replacementN Engl J Med19772972312461249335247

- AndersonFAJrHirshJWhiteKFitzgeraldRHJrHip and Knee Registry InvestigatorsTemporal trends in prevention of venous thromboembolism following primary total hip or knee arthroplasty 1996–2001: findings from the Hip and Knee RegistryChest20031246 Suppl349S356S14668417

- HovensMMSnoepJDTamsmaJTHuismanMWAspirin in the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolismJ Thromb Haemost2006471470147516839339

- BecattiniCAgnelliGSchenoneAWARFASA InvestigatorsAspirin for preventing the recurrence of venous thromboembolismN Eng J Med20123662119591967

- BrightonTAEikelboomJWMannKASPIRE InvestigatorsLow-dose aspirin for preventing recurrent venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med2012367211979198723121403

- ČulićVAspirin for preventing venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med2013368877223425173

- ParaskevasKIAspirin for preventing venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med2013368877277323425174

- BeckerDMSegalJVaidyaDSex differences in platelet reactivity and response to low-dose aspirin therapyJAMA2006295121420142716551714

- KhemasuwanDChaeYKGuptaSDose-related effect of statins in venous thrombosis risk reductionAm J Med2011124985285921783169

- SimesJBecattiniCAgnelliGINSPIRE Study Investigators (International Collaboration of Aspirin Trials for Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism)Aspirin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism: the INSPIRE collaborationCirculation2014130131062107125156992

- SobierajDMColemanCIPasupuletiVDeshpandeAKawRHernandezAVComparative efficacy and safety of anticoagulants and aspirin for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism: a network meta-analysisThromb Res2015135588889625795564

- AndersonDRDunbarMJBohmERAspirin versus low-molecular-weight heparin for extended venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized trialAnn Intern Med20131581180080623732713

- PrandoniPNoventaFMilanMAspirin and recurrent venous thromboembolismPhlebology201328Suppl 19910423482543

- WeitzJIBauersachsRBeyer-WestendorfJEINSTEIN CHOICE InvestigatorsTwo doses of rivaroxaban versus aspirin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolisms. Rationale for and design of the EINSTEIN CHOICE studyThromb Haemost2015114364565025994838

- BozicKJVailTPPekowPSMaselliJHLindenauerPKAuerbachADDoes aspirin have a role in venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in total knee arthroplasty patients?J Arthroplasty20102571053106019679434

- JiangYDuHLiuJZhouYAspirin combined with mechanical measures to prevent venous thromboembolism after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trialChin Med J (Engl)2014127122201220524931228

- StewartDWFreshourJEAspirin for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolic events in orthopedic surgery patients: a comparison of the AAOS and ACCP guidelines with review of the evidenceAnn Pharmacother2013471637423324504

- KnesekDPetersonTMarkelDCThromboembolic prophylaxis in total joint arthroplastyThrombosis20122012837896

- JamesonSSBakerPNDeehanDJPortAReedMREvidence-base for aspirin as venous thromboembolic prophylaxis following joint replacementBone Joint Res20143514614924837005

- ThoratMACuzickJProphylactic use of aspirin: systematic review of harms and approaches to mitigation in the general populationEur J Epidemiol201530151825421783

- FausaOSalicylate-induced hypoprothrombinemia. A report of four casesActa Med Scand197018854034085490567

- GargSKSarkerCRAspirin-induced thrombocytopenia on an immune basisAm J Med Sci197426721291324856606

- WijnjaLSnijderJANiewegHOAcetylsalicylic acid as a cause of pancytopenia from bone-marrow damageLancet1996274677687704162323