Abstract

Background

The burden of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) is increasing in most countries of sub-Saharan Africa. However, as there is a scarcity of data, little is known about CVD in Angola. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of prehypertension, hypertension, prediabetes, diabetes, overweight, and obesity among workers at a private tertiary center in Angola.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 781 workers of Clínica Girassol, a tertiary health care center in Angola, during the month of November 2013. Demographic, anthropometric, and clinical variables were analyzed.

Results

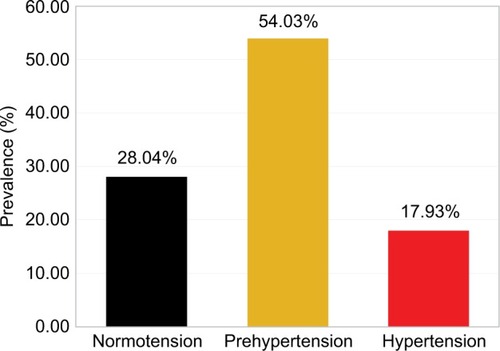

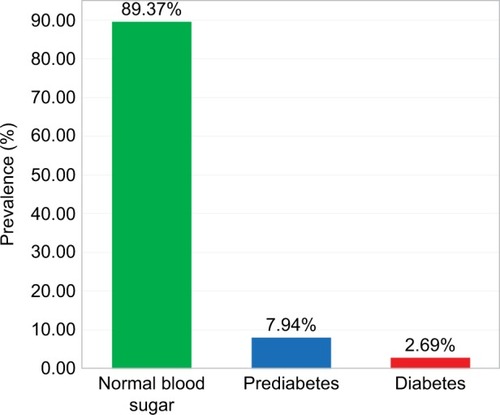

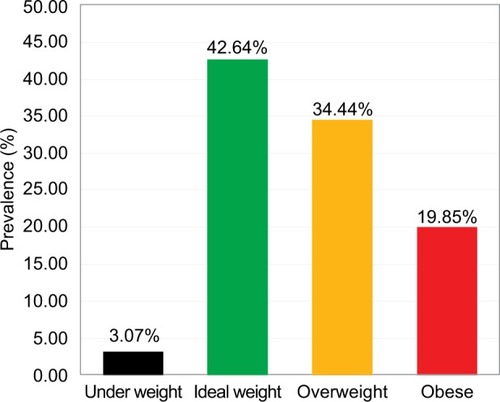

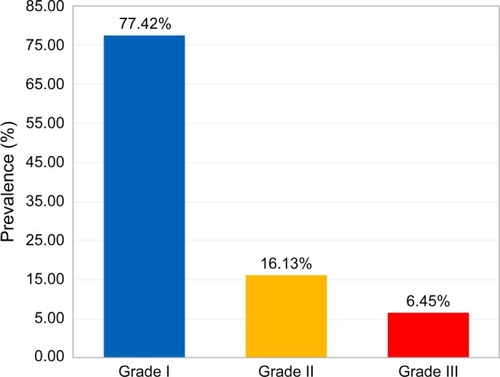

Of the 781 participants studied, 50.44% were males and 78.11% were under 40 years old. The prevalence of hypertension and prehypertension was 17.93% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 15.24%–20.74%) and 54.03% (95% CI: 50.58%–57.62%), respectively. Among hypertensive subjects, 83.57% (117) were unaware of the diagnosis. Hypertension was associated with age (≥40 years) (odds ratio [OR]: 6.21; 95% CI: 4.18–9.24; P<0.001) and with overweight and obesity (OR: 2.32; 95% CI: 1.56–3.44; P<0.001). The prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes was 2.69% (95% CI: 1.54%–3.97%) and 7.94% (95% CI: 6.02%–9.99%), respectively. The prevalence of overweight was 34.44% (95% CI: 31.11%–37.90%) and 19.85% (95% CI: 17.03%–22.79%) for obesity. There was an association between overweight and obesity and the female sex (OR: 1.71; 95% CI: 1.29–2.28; P<0.001). The prevalence of family history of CVD, smoking, and alcoholism was 52.24%, 4.87%, and 45.33%, respectively.

Conclusion

There was a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in apparently healthy workers at the private tertiary center in Angola.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.Citation1,Citation2 About 17.3 million people died from CVD in 2008.Citation2 In recent years, some studies have demonstrated that CVD mortality increased in developing countries,Citation2,Citation3 and these countries have the greatest absolute number of people with hypertension – the main risk factor for CVD. Additionally projections point to a 60% increase in the prevalence of hypertension in developing countries during the period of 2000–2025.Citation4

In sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence of CVD has increased in the last 20 years.Citation5,Citation6 From 1990 to 2010, the three risk factors that showed the highest perceptual increase in the region were the body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP), and blood sugar changes.Citation7 The deaths from CVD in this region presented a parallel increase; and it has been shown that in sub-Saharan Africa deaths due to CVD occur in younger people compared to the rest of the world.Citation3,Citation8 However, the health system of most countries in the region do not have the preparedness to respond to this new reality.Citation9–Citation11 In addition, sub-Saharan Africa remains the region of the world where there is scarcity of data on CVD.Citation8,Citation12,Citation13

In Angola, it was estimated that approximately 27,000 people died from CVD and diabetes mellitus (DM) during 2012.Citation14 Little is known about the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the general population. In the few available studies, the prevalence of hypertension ranged from 23% to 45.2%;Citation15–Citation17 and overweight and obesity 29.3% and 19.6%, respectively.Citation17 The prevalence of DM was 2.8% and 5.7% in urban and rural population, respectively.Citation17,Citation18

Economic changes, industrialization, and the urbanization, which Angola has experienced, are associated with the development of CVD.Citation19,Citation20 The interaction of these factors with other determinants, such as the low level of education, ethnic factors, and health system failures, can increase the impact of CVD on public health;Citation11,Citation14 whereas older problems such as infectious, maternal, and perinatal diseases still represent an important burden (leading to mortality) in the country.Citation8,Citation14,Citation21

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of the main cardiovascular risk factors among workers of a private tertiary center in Angola.

Materials and methods

Design, location, and population of the study

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 781 workers (52.06% of 1,500) of Clínica Girassol during the month of November 2013. The Clínica Girassol is a private tertiary health care center of the Sonangol group, located in Luanda, Angola, with 1,500 workers, aged between 18 and 65 years old (about 75% under the age of 40 years), of different occupational categories, mostly nurses and physicians.

All subjects at work during the month of November 2013 were invited to participate and were included after a written informed consent form was signed.

Study variables

The assessment included a questionnaire, used by previously trained interviewers, with close-ended questions about age, sex, personal medical history, family history of CVD, smoking, and alcoholism. This was followed by the measurement of continuous variables of the study (such as weight, height, capillary glycemia, and BP). We took hypertension, DM, overweight, and obesity as dependent variables and the others as independent variables.

Weight was measured with an electronic digital Seca® scale (Seca, Hamburg, Germany) with a capacity of up to 150 kg and precision of 100 g. The scale was calibrated and certified by the manufacturer, and checked regularly by the clinical engineering service of the institution. Height was measured in centimeters using a stadiometer included in the scale, with maximum extension of 200 cm and precision of 0.1 cm. The BMI was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters (BMI = weight [kg] ÷ height [m2]). Based on the BMI, the population was categorized into subgroups as follow: low weight (<18.5 kg/m2), ideal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥30 kg/m2) using the World Health Organization classification criteria.Citation22 Obesity was classified as Grade I (BMI ≥30.00–34.99), Grade II (BMI ≥35.00–39.99), and Grade III (BMI ≥40.00).Citation22

The capillary blood sugar was measured with a Contour Next® (Bayer Vital, Leverkusen, Germany) instrument. Based on the time from the last food intake, capillary blood sugar was considered fasting glucose (if >8 hours after last meal) or capillary random glucose (if <8 hours after last meal). We considered DM for fasting blood sugar ≥126 mg/dL, or a random blood sugar ≥200 mg/dL, or previous diagnosis of DM with the use of medication, according to the guidelines of American Diabetes Association.Citation23 We considered impaired fasting glucose if fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL, but <126 mg/dL; and impaired glucose tolerance if random capillary blood glucose ≥140 mg/dL, but <200 mg/dL. Impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance were included in a single category of prediabetes.Citation23,Citation24

BP was assessed according to Joint National Committee (JNC)-VII guidelinesCitation25 by using an auscultatory method with an aneroid sphygmomanometer certified by the manufacturer, and the instrument was checked regularly by the clinical engineering service. BP was measured using an appropriately sized cuff for brachial circumference. The measurement was performed on the right arm, after a rest of at least 5 minutes, and in a calm environment. Based on the value of BP, the population was categorized into three subgroups: normotensives (BP <120/80 mmHg); prehypertensives (systolic BP [SBP] from 120 to 139 mmHg and/or diastolic BP [DBP] from 80 to 89 mmHg); and hypertensives (SBP ≥140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥90 mmHg).Citation25 We also considered as hypertensive all those with a previous diagnosis in use of medication, regardless of BP levels.

Statistical analysis

The software Epi info version 7.1.4 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA) was used as a database. Demographic characteristics of the sample were analyzed, and we calculated the prevalence of hypertension, prehypertension, overweight, obesity, prediabetes, and DM in the general sample and also specifically by age and sex. To estimate the association between independent and dependent variables, we used the odds ratio (OR) as a risk measure, with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Frequency comparison between groups was performed by χ2, and, a P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was performed using “OpenEpi”, an online software, version 3.03 (CDC).Citation26

Ethical implications

The study was approved by the Teaching Postgraduate, and Research Office, which is the committee responsible for ethical issues in the Clínica Girassol. The workers were free to choose to participate in the study or not, and they were included only after written informed consent was signed. The researchers guaranteed the preservation of participants’ confidential data, strict and impartial analysis of the results, and the participants diagnosed as diabetic or hypertensive were advised to have a clinical follow-up.

Results

A total of 781 workers were evaluated, and their demographic characteristics are presented in . There was no significant difference between sexes, most workers (78.11%) were aged under 40 years, and were Black Africans.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the study population

Regarding BP 28.04% (n=219; 95% CI: 24.84%–31.37%) of participants had normal BP, 54.03% (n=422; 95% CI: 50.58%–57.62%) had prehypertension, and 17.93% (n=140; 95% CI: 15.24%–20.74%) had hypertension (). Among hypertensive subjects, 83.57% (117) were unaware of their BP status until the time of this evaluation. Hypertension was associated with age (≥40 years) (OR: 6.21; 95% CI: 4.18–9.24; P<0.001) and with overweight and obesity (OR: 2.32; 95% CI: 1.56–3.44; P<0.001), but there was no significant difference between men and women (19.29% vs 16.28%; χ2 =1.01; P=0.27). In the sample, 89.37% (n=698; 95% CI: 87.20%–91.68%) had normal blood sugar; and the prevalence of DM and prediabetes was 2.69% (n=21; 95% CI: 1.54%–3.97%) and 7.94% (n=62; 95% CI: 6.02%–9.99%), respectively (). Among diabetic patients, 90.48% were under treatment and 9.52% were unaware of the diagnosis. DM was associated with age (≥40 years) (OR: 4.13; 95% CI: 1.72–9.89; P<0.001), and individuals who were overweight and obese presented a no significant trend to higher prevalence of DM than those with ideal body weight (3.302% vs 1.961%; χ2 =1.33; P=0.35). Regarding weight, 3.07% (n=24; 95% CI: 1.92%–4.35%) of participants were underweight, 34.44% (n=269; 95% CI: 31.11%–37.90%) overweight, and 19.85% (n=155; 95% CI: 17.03%–22.79%) were obese (). Among 155 workers with obesity, 77.42% had Grade I, 16.13% Grade II, and 6.45% Grade III (). Overweight and obesity was higher in women than men (60.98% vs 47.72%; χ2=13.32; P<0.001).

Figure 1 Blood pressure distribution among the study population.

Figure 2 Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes in study population.

Figure 3 Distribution of the study population according to BMI.

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Figure 4 Distribution of obese subjects according to the grade. Grade I (BMI ≥30.00–34.99), grade II (BMI ≥35.00–39.99), and grade III (BMI ≥40.00).

Family history of CVD, active smoking, and alcoholic beverage consumption was reported by 52.24% (n=408; 95% CI: 48.78%–55.82%), 4.87% (n=38; 95% CI: 2.05%–6.53%), and 45.33% (n=354; 95% CI: 41.87%–48.91%) of workers, respectively. presents the summary of the association between independent and dependent variables, in univariate analysis.

Table 2 Univariate analysis of the association between independent and dependent variables

Discussion

Blood pressure

In this study, we found a prehypertension prevalence of 54.03%, which is considerably high taking into account the average age of the study population. However, it is in concordance with other studies conducted among African populations, in Nigeria and Egypt, where the prevalence was 58.7% and 57.2%, respectively.Citation27,Citation28 This is the first study that evaluated prehypertension in Angola. The high prevalence we found is of paramount importance since the rate of progression from prehypertension to hypertension in follow-up studies was 29% (in 4.1 years) in a Jamaican cohortCitation29 and 30.4% in 3 years of follow-up among postmenopausal women,Citation30 and can reach a high progression rate up to 13.9% per year.Citation31 In addition, we highlight the value of racial factor and BMI, because the Black race was found to be a predictor of faster progressionCitation32 as well as a high BMI.Citation33

On the other hand, regardless of progression, prehypertension is itself a risk factor for coronary artery disease, end-stage renal disease, and cerebrovascular events.Citation34,Citation35 In a meta-analysis of 20 cohort studies with 1,129,098 participants, prehypertension significantly increased mortality due to stroke.Citation36 We emphasize that in African populations, stroke occurs earlier than in rest of the world and is the leading cause of cardiovascular mortality.Citation8 So, a high prevalence, as we found, associated with low awareness and control, may be one of the factors that contribute to this finding.

The prevalence of hypertension was 17.93%, which is nearly the average (16.2%) prevalence of this condition in the regionCitation6,Citation37 and in line with that found in a study in Ethiopia (another country in this region).Citation38 However, it is relatively lower compared to that found in other studies carried out in AngolaCitation15–Citation18 and some other countries in the region such as South Africa, Nigeria, and Uganda.Citation27,Citation39,Citation40 This difference might be due to the younger population in this study (78.11% of them <40 years) compared to the other studies. The difference in prevalence compared to other countries, like South Africa, may be due to the actual differences in the prevalence of risk factors for hypertension.Citation39 There was no statistically significant difference between sexes in the occurrence of hypertension, which is in line with the results reported by other studies carried out in the region.Citation12,Citation41

Among hypertensive subjects, 83.57% were unaware of their status, nearly 78.4% found in another study conducted in northern Angola, where among those who were aware, only 13.9% were under pharmacological treatment and of these, only about one-third had their BP controlled.Citation16

Diabetes mellitus and prediabetes

The prevalence of DM (2.69%) was close to 2.9%, which is the rate estimated for the country’s population by the International Federation of Diabetes for the year 2013;Citation42 but relatively lower than that found in previous studies in the country,Citation17,Citation18 and in neighboring countries (3.5% in southern Congo and 3.9% in South Africa).Citation43,Citation44 The occurrence of DM was significantly associated with age >40 years, which is in line with the results obtained from other studies.Citation18,Citation43 The association with BMI was not statistically significant.

The prevalence of prediabetes (7.94%) was similar to that found in a study in Uganda.Citation45 It is worth remembering that the rate of progression from prediabetes to DM is 6.8% per year.Citation46 And among individuals categorized as prediabetic by both criteria (HbA1c and fasting glucose), the cumulative risk of developing DM was 100% in a 5.6 years’ follow-up study.Citation47 In addition, prediabetes is itself associated with increased risk of cardiovascular mortality.Citation48

Overweight and obesity

In relation to BMI, the combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was 54.29%, which is relatively higher than that of previous studies,Citation15,Citation17 suggesting a trend to increase in prevalence of weight-related problems. This is reinforced when we observe that in a study conducted approximately 10 years ago the prevalence of obesity was significantly lower than in the current (3.2% vs 20%), and there were no individuals with Grade III obesity.Citation15 In this study, overweight and obesity were higher in women, which is in accordance with another study in the country,Citation17 and the global trend;Citation49 and was associated with a higher rate of high BP, as is traditionally reported.Citation50

Other cardiovascular risk factors

In relation to other cardiovascular risk factors, the prevalence of smoking was lower (4.9% vs 7.2%) than that found among public workers in LuandaCitation17 and below the 9.0% estimated for the population of the country for the year 2012.Citation51 The prevalence was higher in men than in women, as found in other countries in the region.Citation52,Citation53 The prevalence of alcohol consumption was in line with that of another study.Citation15 Positive family history of CVD was reported by 52.24% of participants.

Conclusion

The present study shows a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in apparently healthy workers. This exposes the need for more studies to better measure the magnitude of the situation and guide the response planning to this problem.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the use of capillary blood glucose, as well as the consideration of glucose intolerance by random capillary blood glucose (and not 2-hour post 75 g of glucose). These options were adopted because they are more feasible approaches in resource-limited countries. Another limitation is related to the representativeness of the population. However, this is one among few existing studies in the country about the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factor among specific groups, and we believe that this study will serve as a starting point for national studies, which are now very necessary.

Author contributions

FCP and VM analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors contributed to conception and design of the study, performed the data collection, revised, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely acknowledge the hospital board and workers of the Clínica Girassol, Luanda, Angola.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LozanoRNaghaviMForemanKGlobal and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010Lancet201238098592095212823245604

- World Health OrganizationGlobal Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010GenevaWorld Health Organization2010

- VedanthanRSeligmanBFusterVGlobal perspective on acute coronary syndrome: a burden on the young and poorCirc Res2014114121959197524902978

- KearneyPMWheltonMReynoldsKMuntnerPWheltonPKHeJGlobal burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide dataLancet2005365945521722315652604

- AdeloyeDBasquillCEstimating the prevalence and awareness rates of hypertension in Africa: a systematic analysisPLoS One201498e10430025090232

- TwagirumukizaMDe BacquerDKipsJGde BackerGSticheleRVVan BortelLMCurrent and projected prevalence of arterial hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa by sex, age and habitat: an estimate from population studiesJ Hypertens20112971243125221540748

- MensahGADescriptive epidemiology of cardiovascular risk factors and diabetes in sub-saharan AfricaProg Cardiovasc Dis201356324025024267431

- MoranAForouzanfarMSampsonUChughSFeiginVMensahGThe epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases in sub-saharan Africa: the global burden of diseases, injuries and risk factors 2010 studyProg Cardiovasc Dis201356323423924267430

- KengneAPMayosiBMReadiness of the primary care system for non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan AfricaLancet Glob Heal201425e247e248

- Costa MendesIAMarchi-AlvesLMMazzoAHealthcare context and nursing workforce in a main city of AngolaInt Nurs Rev2013601374423406235

- CameronARoubosIEwenMMantel-TeeuwisseAKLeufkensHGLaingRODifferences in the availability of medicines for chronic and acute conditions in the public and private sectors of developing countriesBull World Health Organ201189641242121673857

- DalalSBeunzaJJVolminkJNon-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: what we know nowInt J Epidemiol201140488590121527446

- HertzJTReardonJMRodriguesCGAcute myocardial infarction in sub-Saharan Africa: the need for dataPLoS One201495e9668824816222

- WHONoncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2014 – UKGenevaWorld Health Organization2014 Available from: http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/gbr_en.pdf?ua=1Accessed November 8, 2014

- SimãoMHayashidaMdos SantosCBCesarinoEJNogueiraMSHypertension among undergraduate students from Lubango, AngolaRev Lat Am Enfermagem200816467267818833447

- PiresJESebastiãoYVLangaAJNerySVHypertension in Northern Angola: prevalence, associated factors, awareness, treatment and controlBMC Public Health20131319023363805

- CapinganaDPMagalhãesPSilvaABPrevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and socioeconomic level among public-sector workers in AngolaBMC Public Health201313173223924306

- Evaristo-NetoADFoss-FreitasMCFossMCPrevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in a rural community of AngolaDiabetology & metabolic syndrome2010216321040546

- VorsterHHThe emergence of cardiovascular disease during urbanisation of AfricansPublic Health Nutr200251A23924312027290

- AllenderSLaceyBWebsterPLevel of urbanization and noncommunicable disease risk factors in Tamil Nadu, IndiaBull World Health Organ201088429730420431794

- LimSSVosTFlaxmanADA comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010Lancet201238098592224226023245609

- WHOObesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultationWorld Health Organ Tech Rep Ser2000894ixii1253 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11234459Accessed July 16, 201411234459

- American Diabetes AssociationStandards of medical care in diabetes – 2010Diabetes Care201033Suppl 1S11S6120042772

- World Health OrganizationDefinition and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intermediate HyperglycaemiaGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2006 Available from: http://apps.who.int//iris/handle/10665/43588

- ChobanianAVBakrisGLBlackHRSeventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood PressureHypertension20034261206125214656957

- DeanASullivanKSoeMOpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health2011 Available from: www.OpenEpi.comAccessed November 8, 2014

- IsezuoSASabirAAOhwovoriloleAEFasanmadeOAPrevalence, associated factors and relationship between prehypertension and hypertension: a study of two ethnic African populations in Northern NigeriaJ Hum Hypertens201125422423020555358

- AhmedNArafaSEz-elarabHSEpidemiology of prehypertension and hypertension among egyptian adults introductionEgypt J Community Med2011291118 Available from: https://scholar.google.com.br/scholar?cluster=14268895851298319893&hl=en&as_sdt=2005&sciodt=0,5Accessed November 8, 2014

- FergusonTSYoungerNTulloch-ReidMKProgression from prehypertension to hypertension in a Jamaican cohort: incident hypertension and its predictorsWest Indian Med J201059548649321473394

- ZambranaRELópezLDinwiddieGYPrevalence and incident prehypertension and hypertension in postmenopausal hispanic women: results from the women’s health initiativeAm J Hypertens201427337238124480867

- ZhengLSunZZhangXPredictors of progression from prehypertension to hypertension among rural Chinese adults: results from Liaoning ProvinceEur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil201017221722220010427

- HsiaJMargolisKLEatonCBPrehypertension and cardiovascular disease risk in the women’s health initiativeCirculation2007115785586017309936

- TomiyamaHMatsumotoCYamadaJPredictors of progression from prehypertension to hypertension in Japanese menAm J Hypertens200922663063619265783

- HuangYWangSCaiXPrehypertension and incidence of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysisBMC Med201311117723915102

- HuangYCaiXZhangJPrehypertension and incidence of ESRD: a systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Kidney Dis2014631768324074825

- HuangYSuLCaiXAssociation of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality with prehypertension: a meta-analysisAm Heart J20141672160168.e124439976

- OgahOSRaynerBLRecent advances in hypertension in sub-Saharan AfricaHeart20133032271918

- NshissoLDReeseAGelayeBLemmaSBerhaneYWilliamsMAPrevalence of hypertension and diabetes among Ethiopian adultsDiabetes Metab Syndr201261364123014253

- TibazarwaKNtyintyaneLSliwaKA time bomb of cardiovascular risk factors in South Africa: results from the heart of Soweto Study “Heart Awareness Days”Int J Cardiol2009132223323918237791

- MaherDWaswaLBaisleyKKarabarindeAUnwinNGrosskurthHDistribution of hyperglycaemia and related cardiovascular disease risk factors in low-income countries: a cross-sectional population-based survey in rural UgandaInt J Epidemiol201140116017120926371

- OnwuchekwaACTobin-WestCBabatundeSPrevalence and risk factors for stroke in an adult population in a rural community in the Niger Delta, South-South NigeriaJ Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis201423350551023721622

- GuariguataLWhitingDRHambletonIBeagleyJLinnenkampUShawJEGlobal estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035Diabetes Res Clin Pract2014103213714924630390

- KatchungaPMasumbukoBBelmaMKashongwe MunogoloZHermansMPM’Buyamba-KabanguJRAge and living in an urban environment are major determinants of diabetes among South Kivu Congolese adultsDiabetes Metab201238432433122483839

- MotalaAAEsterhuizenTGouwsEPirieFJMahomedAKDiabetes and other disorders of glycemia in a rural South African community: prevalence and associated risk factorsDiabetes Care20083191783178818523142

- MayegaRWGuwatuddeDMakumbiFDiabetes and pre-diabetes among persons aged 35 to 60 years in Eastern Uganda: prevalence and associated factorsPLoS One201388e7255423967317

- AngYGWUCXTohMPChiaKSHengBHProgression rate of newly diagnosed impaired fasting glycemia to type 2 diabetes mellitus: a study using the National Healthcare Group Diabetes Registry in SingaporeJ Diabetes20124215916322059651

- HeianzaYAraseYFujiharaKScreening for pre-diabetes to predict future diabetes using various cut-off points for HbA1c and impaired fasting glucose: the Toranomon Hospital Health Management Center Study 4 (TOPICS 4)Diabet Med2012299e279e28522510023

- BarrELZimmetPZWelbornTARisk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity, and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab)Circulation2007116215115717576864

- NgMFlemingTRobinsonMGlobal, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013Lancet2014384994576678124880830

- RahmouniKCorreiaMLHaynesWGMarkALObesity-associated hypertension: new insights into mechanismsHypertension200545191415583075

- NgMFreemanMKFlemingTDSmoking prevalence and cigarette consumption in 187 countries, 1980–2012Jama2014311218319224399557

- TranAGelayeBGirmaBPrevalence of metabolic syndrome among working adults in EthiopiaInt J Hypertens2011201119371921747973

- AddoJSmeethLLeonDASmoking patterns in Ghanaian civil servants: changes over three decadesInt J Environ Res Public Health20096120020819440277