Abstract

The safety of angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) for the treatment of hypertension and cardiovascular and renal diseases has been well documented in numerous randomized clinical trials involving thousands of patients. However, recent concerns have surfaced about possible links between ARBs and increased risks of myocardial infarction and cancer. Less is known about the safety of the direct renin inhibitor aliskiren, which was approved as an antihypertensive in 2007. This article provides a detailed review of the safety of ARBs and aliskiren, with an emphasis on the risks of cancer and myocardial infarction associated with ARBs. Safety data were identified by searching PubMed and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Web sites through April 2011. ARBs are generally well tolerated, with no known class-specific adverse events. The possibility of an increased risk of myocardial infarction associated with ARBs was suggested predominantly because the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-Term Use Evaluation (VALUE) trial reported a statistically significant increase in the incidence of myocardial infarction with valsartan compared with amlodipine. However, no large-scale, randomized clinical trials published after the VALUE study have shown a statistically significant increase in the incidence of myocardial infarction associated with ARBs compared with placebo or non-ARBs. Meta-analyses examining the risk of cancer associated with ARBs have produced conflicting results, most likely due to the inherent limitations of analyzing heterogeneous data and a lack of published cancer data. An ongoing safety investigation by the FDA has not concluded that ARBs increase the risk of cancer. Pooled safety results from clinical trials indicate that aliskiren is well tolerated, with a safety profile similar to that of placebo. ARBs and aliskiren are well tolerated in patients with hypertension and certain cardiovascular and renal conditions; their benefits outweigh possible safety concerns.

Introduction

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) consists of a group of hormones, which regulates blood pressure (BP), fluid and electrolyte balance, tissue perfusion, and vascular growth.Citation1,Citation2 The RAS plays an important role in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular and renal disease,Citation3 and antihypertensive therapies that target the RAS are used in the management of hypertension, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, high cardiovascular risk, diabetes, and renal failure.Citation2,Citation3 In addition, antihypertensive drugs that block the RAS may provide organ protection by acting on local RAS functions in tissues, such as the kidneys, heart, eyes, and brain.Citation2,Citation3

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (eg, ramipril, captopril, enalapril, fosinopril) were the first class of RAS-blocking agents to become available, and ACE inhibitors have been a cornerstone of antihypertensive therapy for many years.Citation4 Numerous clinical trials have shown that the BP-lowering effects of ACE inhibitors provide cardiovascular protection;Citation5 however, ACE inhibitors are associated with treatment-related adverse events (AEs) including persistent dry coughCitation6,Citation7 and angioedema.Citation8 Both of these AEs are more common among black and Asian patients compared with white patients,Citation5,Citation8 and cough is also more common among women and nonsmokers.Citation7 Cough is typically managed by discontinuing ACE inhibitor therapy or by decreasing the dose. Antitussives and antihistamines are usually ineffective for managing cough; however, in some cases cough may disappear spontaneously.Citation6 Strategies for managing angioedema include discontinuation of ACE inhibitor therapy and/or treatment with antihistamines or epinephrine.Citation8 Further, although several case reports have suggested a relationship between the use of ACE inhibitors and development of cancer, case-control and longitudinal studies have shown no relationship and, in some cases, a protective effect from treatment.Citation9,Citation10

Over the last two decades, several angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs; eg, losartan, valsartan, telmisartan, olmesartan) have been approved as antihypertensive therapies.Citation11 ARBs provide clinically meaningful benefits for patients with cardiovascular and/or renal disease,Citation11 and ARBs generally have better tolerability profiles than ACE inhibitors.Citation12 Cough is not an AE associated with ARB therapy; however, when ARBs are used in combination with ACE inhibitors, there is an increased risk of renal dysfunction and hyperkalemia.Citation4 Over the past several years, concerns have surfaced about possible links between ARBs and increased risks of cancerCitation13 and myocardial infarction.Citation14

Direct renin inhibitors (DRIs) are a new class of anti-hypertensive agents that target the initial rate-limiting step of the RAS.Citation15 Several DRIs have been developed as antihypertensive therapies; however, early DRIs, including enalakiren, remikiren, and zankiren, had poor bioavailability, weak antihypertensive effects, and short durations of action.Citation4,Citation15 Aliskiren is the only DRI that is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of hypertension,Citation16 but several other DRIs are in the early stages of clinical development.Citation17,Citation18 In clinical studies, the AE profile of aliskiren was similar to that of placebo, with a lower incidence of cough than ACE inhibitors.Citation15,Citation16

The main purpose of this article is to review the safety of ARBs and the DRI aliskiren, including a detailed examination of the risks of cancer and myocardial infarction associated with ARBs. A brief overview of the RAS and efficacy of ARBs and aliskiren is also provided.

Overview of the RAS

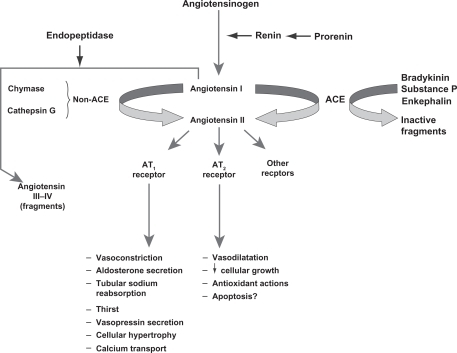

Key steps in the RAS are shown in .Citation3 Following conversion from its precursor prorenin, the aspartate protease renin is secreted by granular cells of the juxtaglomerular apparatus in the kidney.Citation3,Citation19 The biosynthesis and release of renin are key elements in determining the capacity of the RAS to regulate BP and respond to fluid changes.Citation3 Renin catalyzes the conversion of angiotensinogen to angiotensin I, which is the rate-limiting step in the RAS.Citation15 DRIs block this step and reduce plasma renin activity.Citation15 ACE catalyzes the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, and ACE inhibitors block this step in the RAS.Citation15 Angiotensin II binds to angiotensin II type-1 (AT1) receptors, which regulates BP via several mechanisms and provides feedback inhibition of further release of renin by the kidneys.Citation15 ARBs block the AT1 receptor, reducing the effects of angiotensin II.Citation4

Figure 1 Overview of the renin-angiotensin system.

Reproduced with permission of the American Society of Nephrology, from ‘The renin-angiotensin system as a risk factor and therapeutic target for cardiovascular and renal disease’, Volpe et al, volume 13, supplement 3, 2002; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.Citation3

ARBs and ACE inhibitors may not provide comprehensive suppression of the RAS because they disrupt the negative feedback effect of angiotensin II on renin release, resulting in an increase in plasma renin concentration and plasma renin activity.Citation2,Citation4 ACE inhibitors also increase angiotensin I concentrations, and although ACE inhibitors prevent the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, angiotensin II production can still occur through non-ACE–dependent pathways involving enzymes such as chymase and chymotrypsin-like angiotensin-generating enzyme.Citation1,Citation15 In addition, ACE inhibitors block the degradation of bradykinin, and the resulting increase in bradykinin concentration may be a factor in the development of cough and angioedema associated with these agents.Citation15 DRIs may provide more optimal suppression of the RAS by interrupting the system at its first regulated step, resulting in decreased plasma renin activity.Citation1,Citation2,Citation15

Efficacy of ARBs and the DRI aliskiren

In 1995, losartan was the first ARB to receive FDA approval as an antihypertensive. Since then, six other ARBs and the DRI aliskiren have also been approved for the treatment of hypertension; several of these agents also have other cardiovascular indications.Citation20 Approved indications, dosing information, and dates of FDA approval for the ARBs and aliskiren are shown in .

Table 1 Approved indications, usual starting and maintenance dosing,Table Footnotea and FDA approval dates for ARBs and aliskiren

ARBs

Data from numerous randomized clinical trials indicate that ARB therapy is effective in reducing complications related to hypertensionCitation5 and in slowing or blocking the progression of cardiovascular disease.Citation11 As a class of drugs, ARBs have shown clinical benefits for patients with heart failure, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease.Citation5 Pharmacologic and dosing differences exist among the seven ARBs approved as antihypertensive agents;Citation11,Citation20 therefore, efficacy and safety results for one ARB cannot be extrapolated to other ARBs.Citation20 In general, newer ARBs are more effective than losartan in lowering BP in patients with hypertension based on the results of head-to-head comparative studies.Citation11 Recent reviewsCitation11,Citation20 have compared the efficacy of ARBs vs non-ARBs in different clinical settings. These results are summarized in .

Table 2 Selected outcomes from randomized clinical trials of ARBs

The DRI aliskiren

The effects of aliskiren on cardiovascular and renal morbidity and mortality are currently unknown. However, several outcomes studies are underway as part of the ASPIRE HIGHER clinical trials program, which will help to better define the role of direct renin inhibition in clinical practice.Citation1

When administered alone or in combination with other agents, including thiazide diuretics, calcium-channel blockers, or RAS-blocking drugs (ie, ACE inhibitors or ARBs), treatment with aliskiren effectively lowers BP in a variety of hypertensive populations (eg, diabetic, obese, elderly).Citation1,Citation21 In several randomized, double-blind clinical trials, treatment with aliskiren has been associated with positive effects on surrogate markers of cardiovascular and renal disease, including urinary albumin, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), and left ventricular mass index.Citation22–Citation24 For example, in the Aliskiren in the Evaluation of Proteinuria in Diabetes (AVOID) trial in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes with nephropathy,Citation22 aliskiren 300 mg/day combined with losartan 100 mg/day reduced the mean urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio by 20% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 9% to 30%; P < 0.001) compared with losartan 100 mg/day plus placebo. In the Aliskiren Observation of Heart Failure Treatment (ALOFT) trialCitation23 involving patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II to IV heart failure and a history of hypertension, addition of aliskiren to an ACE inhibitor (or ARB) and β-blocker significantly reduced NT-proBNP concentrations compared with placebo. In the Aliskiren in Left Ventricular Hypertrophy (ALLAY) trial,Citation24 which included overweight patients with hypertension and increased ventricular wall thickness, treatment with aliskiren or losartan resulted in similar reductions in left ventricular mass index.

In a recent study (Aliskiren Study in Post-MI Patients to Reduce Remodeling [ASPIRE]), adding aliskiren to standard therapy (ie, statins, beta-blockers, antiplatelets, and either ACE inhibitors [given to 90% of the patients] or ARBs [10% of the patients]) in the weeks following an acute myocardial infarction gave no further protection against ventricular remodeling.Citation25 However, the researchers conducted a post-hoc subgroup analysis and found that patients with diabetes (n = 148) were the only subgroup that had a borderline interaction in treatment effect. There were more AEs in patients assigned to aliskiren, but the total number of serious AEs was similar in the two arms. Specifically, AEs that occurred at a higher incidence in aliskiren recipients compared with placebo recipients included hyperkalemia (5.2% vs 1.3%), hypotension (8.8% vs 4.5%), and renal dysfunction (2.4% vs 0.8%). Elevations in blood urea nitrogen and creatinine were more likely in the aliskiren group, and patients assigned to aliskiren were more likely to have a potassium value measured at >5.5 mmol/L or at ≥6 mmol/L. Although these results do not provide support for testing the use of aliskiren in a morbidity and mortality trial in this population of high-risk postmyocardial infarction patients, ASPIRE used a surrogate endpoint and was not powered to assess hard clinical outcomes. Aliskiren is currently being studied in ongoing outcomes trials of patients with chronic heart failure and diabetic nephropathy to assess the role of direct renin inhibition in these populations.

Safety of ARBs and the DRI aliskiren

Safety of ARBs

As a class of agents, ARBs are well tolerated, with safety profiles similar to that of placebo. No class-specific AEs have been associated with ARBs.Citation26 ARBs are contraindicated for women who are pregnant or may become pregnant because of the risk of fetal developmental abnormalities, and ARBs are not recommended for women who are breastfeeding.Citation5 Several antihypertensive drugs have been associated with an increased risk of erectile dysfunction (ED); however, ARBs have not been observed to increase the risk of ED.Citation5 In patients whose renal function may depend on the activity of the RAS (eg, patients with severe congestive heart failure), treatment with ARBs may be associated with oliguria and/or progressive azotemia; rarely, acute renal failure and/or death have been reported in these patients. ARBs may also increase serum creatinine and/or blood urea nitrogen levels in patients with unilateral or bilateral renal-artery stenosis.Citation27,Citation28

ARBs and myocardial infarction

In 2004, an editorial by Verma and StraussCitation14 raised concerns that ARBs may increase the risk of myocardial infarction based on results of the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-Term Use Evaluation (VALUE) trial,Citation29 which reported a statistically significant 19% relative increase in myocardial infarction with valsartan compared with the calcium-channel blocker amlodipine. Responses to this article from the medical community were mixed. Several follow-up editorials and analysesCitation30–Citation33 cited the need to evaluate the risk of myocardial infarction associated with ARBs more systematically and in a broader clinical context. However, other publications noted that there are possible mechanisms by which ARBs could predispose patients to myocardial infarction.Citation12,Citation34

In 2006, Strauss and HallCitation12 used the term “ARB-MI Paradox” to describe the unexpected observation that in some clinical trials involving patients at high cardiovascular risk, the BP-lowering effects of ARBs did not reduce the risk of myocardial infarction compared with placebo, and in some cases treatment with ARBs may have increased the risk of myocardial infarction. The authors went on to provide a plausible biological mechanism by which ARBs could increase the incidence of myocardial infarction by increasing circulating levels of angiotensin II. Increased angiotensin II levels cause up-regulation of angiotensin type-2 (AT2) receptors. While AT2-receptor stimulation may provide beneficial effects by mediating vasodilation and nitric oxide release, AT2-receptor stimulation may also mediate growth promotion, fibrosis, and hypertrophy, and may have pro-atherogenic and pro-inflammatory effects. The authors concluded that results from meta-analysesCitation35–Citation38 support the “ARB-MI Paradox” because they show that ARBs are associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease events and/or a lack of BP-related vascular benefits.

Following the publication of the editorial by Verma and Strauss,Citation14 several meta-analyses were performed analyzing cardiovascular event outcomes across multiple clinical trials involving ARBs. Results of these analyses were mixed, with some studies reporting no increased risk of myocardial infarction associated with ARBs,Citation33,Citation35,Citation36 while other studiesCitation12,Citation39 report a trend toward increased risk of myocardial infarction with ARBs. While meta-analyses can be powerful tools to summarize data across multiple studies, they also have significant limitations.Citation40 Identification and selection of studies can be biased and availability of results may limit the analyses that can be performed. The choice of statistical analysis methods (ie, fixed-effects vs random-effects models) can also affect the outcome of the meta-analysis. In addition, heterogeneity of data between different studies (eg, disease states, follow-up time, treatment regimens) may make it difficult to create a meaningful integration of results.Citation40 Limitations specifically acknowledged in the meta-analyses that evaluated the risk of myocardial infarction associated with ARBs included heterogeneity of data across studies, limited availability of data on the incidence of myocardial infarction, varying definitions of myocardial infarction between studies, and the potential for confounding effects of different treatments on the incidence of myocardial infarction.Citation35,Citation36

shows the incidence of myocardial infarction reported in randomized clinical trials of ARBs that had a mean or median follow-up time of at least 1 year and enrolled at least 1000 patients with a range of cardiovascular and renal conditions. Since the publication of the Verma and Strauss editorial,Citation14 considerably more data have become available on the incidence of myocardial infarction in patients treated with ARBs. Eight landmark, randomized clinical trials involving ARBs have been completed since 2004. None of these trials has shown a statistically significant increase in the incidence of myocardial infarction associated with ARBs compared with placebo or non-ARB active comparators; however, one study (Efficacy of Candesartan on Outcome in Saitama Trial [E-COST])Citation41 in Japanese patients with essential hypertension reported a statistically significant decrease in the risk of myocardial infarction associated with candesartan compared with conventional therapy (relative risk [RR]: 0.44; 95% CI: 0.21–0.84; P < 0.05).

Table 3 Fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction in clinical trials of ARBs

In the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET) study,Citation42 which enrolled patients with vascular disease or high-risk diabetes, the RR for fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction was 1.07 (95% CI: 0.94–1.22) for telmisartan compared with the ACE inhibitor ramipril. The RR for myocardial infarction for combination therapy with telmisartan and ramipril vs ramipril alone was 1.08 (95% CI: 0.94–1.23).Citation42 In the Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) study,Citation43 which also included patients with diabetes with end-organ damage, the incidence of myocardial infarction was 3.9% (116/2954) in patients treated with telmisartan and 5.0% (147/2972) in patients who received placebo (hazard ratio [HR] for telmisartan vs placebo, 0.79; 95% CI: 0.62–1.01; P = 0.059).Citation43 Results of the Nateglinide And Valsartan in Impaired Glucose Tolerance Outcomes Research (NAVIGATOR) studyCitation44 showed that the event rate for fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction was not significantly different for valsartan compared with placebo in patients with impaired glucose tolerance and cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular risk factors (HR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.77–1.23; 1-sided P = 0.41; 2-sided P = 0.83). In the KYOTO HEART study,Citation45 in Japanese patients with uncontrolled hypertension, the HR for acute myocardial infarction for valsartan compared with non-ARB antihypertensive treatment was 0.65 (95% CI: 0.2–1.8; P = 0.39). Results from the Jikei Heart StudyCitation46 in Japanese patients with hypertension, coronary heart disease, and/or heart failure showed a HR for new or recurrent acute myocardial infarction of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.47–1.74; P = 0.75) for valsartan compared with non-ARB therapy.

The Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Systolic Function (I-PRESERVE)Citation47 and Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes (PROFESS)Citation48 studies did not report statistical analyses for the difference in the incidence of myocardial infarction between ARBs (irbesartan and telmisartan, respectively) and placebo; however, the incidences of myocardial infarction were numerically similar between the ARBs and placebo (), and no significant differences were observed in the HR for death from cardiovascular causes. In the I-PRESERVE study,Citation47 the HR for death from a cardiovascular cause or nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke was 0.99 (95% CI: 0.86–1.13; P = 0.84) for irbesartan vs placebo, and in the PROFESS study,Citation48 the HR for death from cardiovascular causes, recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, or new or worsening heart failure was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.87–1.01; P = 0.11) for telmisartan vs placebo.

Two other landmark randomized clinical trials involving ARBs are not listed in because the published results of these studies did not report the incidence of myocardial infarction. The Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val-HeFT) studyCitation49 evaluated the effects of valsartan as add-on therapy to standard treatment for heart failure in patients with NYHA class II, III, or IV heart failure. In this study, treatment with valsartan reduced the incidence of mortality and morbidity (defined as cardiac arrest with resuscitation, hospitalization for heart failure, or receipt of intravenous inotropic or vasodilator therapy for ≥4 hours) by 13.2% compared with placebo (RR: 0.87; 97.5% CI: 0.77–0.97; P = 0.009). Results of the Morbidity and Mortality After Stroke, Eprosartan Compared With Nitrendipine for Secondary Prevention (MOSES) trialCitation50 showed that the incidence density ratio for cardiovascular events (including myocardial infarction and new cardiac failure) over a mean follow-up time of 2.5 years was lower for eprosartan compared with the calcium-channel blocker nitrendipine (0.75; 95% CI: 0.55–1.02; P = 0.06) in patients with hypertension and history of stroke.

ARBs and cancer

A possible link between an increased incidence of cancer and the use of antihypertensive drugs, including β-blockers, calcium-channel blockers, diuretics, and the alkaloid reserpine, has been suggested by several studies.Citation9 However, the majority of these possible associations remain unproven or highly uncertain.Citation9

Results from animal studies have suggested a possible biological mechanism by which ARBs could increase tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis through selective blockade of AT1 receptors.Citation51 This selective blockade results in increased stimulation of AT2 receptors by angiotensin II. Studies in miceCitation52,Citation53 have shown that AT2-receptor blockade and gene deletion is associated with decreased expression of pro-angiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor and increased expression of thrombospondin-1.

A recent meta-analysis by Sipahi and colleaguesCitation13 found a modestly increased risk of cancer associated with ARBs. Based on an analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials that had a follow-up of at least 1 year, the risk of developing new cancer was 7.2% (2510/35015) among patients treated with ARBs, compared with 6.0% (1602/26575) for controls (RR: 1.08; 95% CI: 1.01–1.15; P = 0.016). In the trials included in this analysis, telmisartan was the study drug for 85.7% (n = 30014) of patients who received an ARB. Analysis of the trials involving telmisartan showed that the RR for development of new cancer in patients treated with telmisartan compared with controls was 1.07 (95% CI: 1.00–1.14; P = 0.05).

The authorsCitation13 also analyzed the results of 5 trials (N = 68 402) for the occurrence of common types of solid organ cancers (ie, breast, lung, and prostate cancer); these results are summarized in . New lung cancer occurred more frequently in patients treated with ARBs (0.9% [361/38 422]) than in control groups (0.7% [195/29 980]; RR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.05–1.49; P = 0.01); no significant differences were observed for prostate or breast cancers. Based on the results of 8 trials that reported cancer deaths, no significant difference was observed between ARBs and controls in the incidence of cancer deaths (1.8% [n = 959/53 424] for ARBs vs 1.6% [n = 639/40 091] for controls; RR: 1.07; 95% CI: 0.97–1.18; P = 0.183).

Table 4 Incidence of solid organ cancers reported in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of ARBs

In addition to the limitations of meta-analyses discussed previously,Citation40 there are several limitations specific to the meta-analysis performed by Sipahi and colleaguesCitation13 that should be considered when interpreting these results. The duration of follow-up in the trials included in this meta-analysis ranged from 1.9–4.8 years. Because cancer is a relatively rare occurrence in any time period of less than 5 years, it has been argued that the duration of follow-up in these trials was too short to draw any meaningful conclusions about the development of new cancers.Citation54 In addition, development of cancer is a relatively rare AE, and rare AEs are often not analyzed statistically in randomized clinical trials because of small sample sizes; this problem can persist even when data are pooled.Citation40 It is also important to note that these results are based on post-hoc analyses, and the primary studies were not designed to test for the development of cancer.Citation13 Further, it is not appropriate to draw conclusions about a possible class effect for all ARBs based on results of this meta-analysis because telmisartan was the study drug in 85.7% of patients who received ARBs. Because the different ARBs have unique pharmacologic and dosing properties,Citation20 results heavily weighted for telmisartan cannot be extrapolated to the entire class of medications. As noted by Sipahi and colleagues, publication bias was also a significant limiting factor in this meta-analysis. There is a lack of published and/or publicly available information on the incidence of cancer observed in clinical trials of ARBs.Citation20 Specifically, many large trials (eg, VALUE,Citation29 Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly [SCOPE]Citation55) did not collect cancer data or did not provide their cancer data to the authors of this study; of 60 trials identified as meeting the inclusion criteria for this analysis, data on cancer incidence and/or cancer deaths were only available from nine trials.Citation13 In addition, the authors of this meta-analysis did not have access to patient-level data to determine whether factors such as age, sex, and smoking status may have influenced the results.Citation13

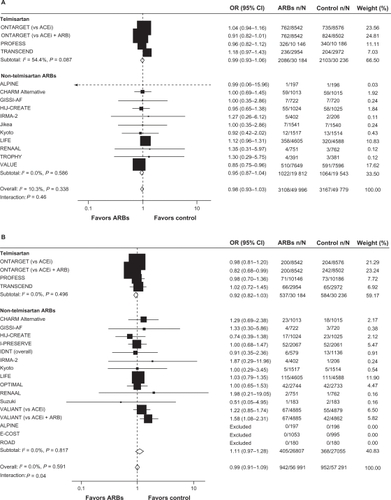

Subsequently, a second meta-analysisCitation56 was performed to assess whether there is an increased risk of cancer associated with antihypertensive therapy. Results of this analysisCitation56 refuted the results of the Sipahi study.Citation13 In their meta-analysis, Bangalore and colleagues identified 70 randomized clinical trials of antihypertensive agents (ARBs, ACE inhibitors, calcium-channel blockers, and diuretics) involving 324,168 patients and found no increased risk of cancer associated with ARBs compared with placebo or other antihypertensive controls using random-effects and fixed-effect models ().Citation56 However, in a fixed-effect model, the combination of ARBs with ACE inhibitors was associated with an increased cancer risk compared with placebo and compared with ARBs (). When the results of individual trials of ARBs were evaluated for cancer risk and cancer-related death, ARBs did not differ significantly vs comparators (). In addition, results did not differ for telmisartan compared with other ARBs.

Figure 2 ARBs and cancer risk A) and cancer-related death B), stratified by ARB type (telmisartan or other).

Reprinted from The Lancet Oncology, volume 12, issue 1, Bangalore et al, ‘Antihypertensive drugs and risk of cancer: network meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of 324 168 participants from randomised trials’, pp 65–82, Copyright 2011, with permission from Elsevier.Citation56

Abbreviations: ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ALPINE, Antihypertensive Treatment and Lipid Profile in a North of Sweden Efficacy Evaluation; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; CHARM, Candesartan in Heart failure Assessment in Reduction of Mortality; CI, confidence interval; E-COST, Efficacy of Candesartan on Outcome in Saitama Trial; GISSI-AF, Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico–Atrial Fibrillation; HIJ-CREATE, Heart Institute of Japan Candesartan Randomized Trial for Evaluation in Coronary Artery Disease; IDNT, Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial; I-PRESERVE, Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Systolic Function; IRMA-2, Irbesartan in Microalbuminuria, Type 2 Diabetic Nephropathy Trial; LIFE, Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension; OPTIMAL, Optimal Trial In Myocardial Infarction With the Angiotensin Receptor Blocker Losartan; ONTARGET, Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial; OR, odds ratio; PROFESS, The Prevention Regimen For Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes Trial; RENAAL, Reduction of Endpoints in Non-insulin-dependent Diabetes Mellitus With Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan; ROAD, Renoprotection of Optimal Antiproteinuric Doses; TRANSCEND, Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease; TROPHY, Trial of Prevention of Hypertension; VALIANT, Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction; VALUE, Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-Term Use Evaluation.

Table 5 Risk of cancer and cancer-related death with ARBs

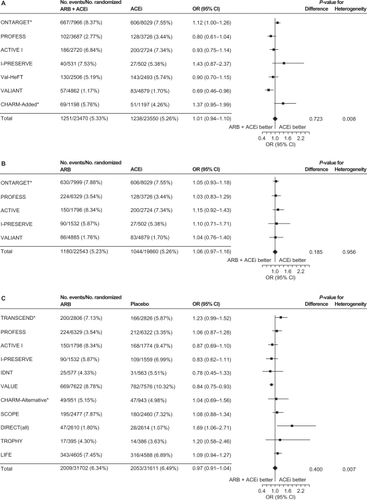

A third meta-analysis,Citation57 conducted by the ARB Trialists Collaboration, evaluated the incidence of cancer in 15 long-term, randomized, controlled trials that involved 138,769 patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease who received ARBs (telmisartan, irbesartan, valsartan, candesartan, or losartan). In this analysis, the trials included were required to have an average follow-up time of at least 12 months. Similar to the Bangalore meta-analysis,Citation56 no increased risk of cancer with ARBs was identified; the cancer incidence in the 15 trials was 6.16% (4549/73,808) in the ARB groups vs 6.31% (3856/61 106) in the control groups (odds ratio [OR]: 1.00; 95% CI: 0.95–1.04; P = 0.886). In addition, no increased cancer risk was observed when evaluating the individual ARBs, and no differences were observed in the incidences of lung, prostate, or breast cancers between ARBs and controls. This analysis also examined cancer risk of ARB/ACE inhibitor combinations vs ACE inhibitors alone, ARBs alone vs ACE inhibitors alone, and ARBs vs placebo/controls without ACE inhibitors. No increased risk of cancer was observed in any of these overall comparisons (). A nominal increase in cancer risk was observed with the ARB/ACE inhibitor combination in one trial (ONTARGET) but a reduced cancer risk was observed with this combination in another (VALIANT). Thus, the authors concluded that the increased risk of cancer observed with the ARB/ACE inhibitor combination may be due to chance and that further study is needed to resolve this question.

Figure 3 Incidence of cancer with A) ARB/ACE inhibitor combination vs ACE inhibitor alone, B) ARB alone vs ACE inhibitor alone, and C) ARB vs placebo/control with no ACE inhibitor.

Reprinted from the Journal of Hypertension, volume 29, issue 4, the ARB trialists collaboration, ‘Effects of telmisartan, irbesartan, candesartan, and losartan on cancers in 15 trials enrolling 138 769 individuals’, pp 623–635, Copyright 2011, with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health.Citation57

Abbreviations: ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ACTIVE, Atrial Fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial With Irbesartan for Prevention of Vascular Events; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CHARM, Candesartan in Heart failure Assessment in Reduction of Mortality; CI, confidence interval; DIRECT, Diabetic Retinopathy Candesartan Trials; IDNT, Irbesartan in Diabetic Nephropathy Trial; I-PRESERVE, Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Systolic Function; LIFE, Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension; ONTARGET, Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial; OR, odds ratio; PROFESS, The Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes Trial; SCOPE, Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly; TRANSCEND, Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects With Cardiovascular Disease; TROPHY, Trial of Prevention of Hypertension; Val-HeFT, Valsartan Heart Failure Trial; VALIANT, Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction; VALUE, Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-Term Use Evaluation.

Because cancer was not a prespecified outcome in most randomized clinical trials involving ARBs, the amount of published information discussing cancer rates in individual randomized clinical trial results is limited. The authors of both the SipahiCitation13 and BangaloreCitation56 studies searched FDA dockets for information on cancer submitted to the FDA during drug approval processes, labeling changes, and FDA meeting minutes. The authors of the Bangalore studyCitation56 also contacted authors and study investigators via email to obtain additional unpublished cancer data. The authors of the ARB Trialists analysisCitation57 had access to individual data for several studies with prespecified methods for cancer identification and tabulated cancer outcomes data for the other trials.

The BangaloreCitation56 and ARB TrialistsCitation57 meta-analyses were more robust than the Sipahi meta-analysisCitation13 because more trials were included and multiple comparison analysis was performed on the network of different treatments. However, the authors of the Bangalore studyCitation56 acknowledge several limitations including the possibility that the survival benefit associated with antihypertensive therapy compared with placebo may have introduced a “survival bias” that increased the incidence of cancer in active treatment groups. For all the meta-analyses, there may have been other confounding variables that are nearly impossible to measure, such as exposure to radiation or carcinogens. None took into consideration the incidence of a specific cancer in the general population. In addition, the selection criteria used to include trials in these meta-analyses could have influenced the findings (ie, certain trials when put together could increase, decrease, or have no effect on cancer risk). Moreover, results are limited by the short-term nature of most trials and the relatively short duration of exposure to the drugs in question to determine cancer risk. Finally, publication bias, issues with heterogeneity, and availability of data can affect any meta-analysis.

Several population-based studies have evaluated the association between antihypertensive treatment and cancer over the years. A recent analysis by Huang and colleagues specifically investigated the association between ARBs and the occurrence of new cancers in 109,002 patients with newly diagnosed hypertension.Citation58 Patients were identified from a random sample of 1 million individuals of mostly Chinese ethnicity using the Taiwanese National Health Insurance database. Over an average follow-up period of 5.7 years, a total of 9067 cases of new cancer were reported with a signif icantly lower occurrence among patients receiving ARBs than not receiving ARBs (3082 vs 5985; P < 0.001). This was the case after adjusting for age, sex, comorbidities, and medications for hypertension control (HR: 0.66; 95% CI: 0.63–0.68; P < 0.001). Consistent results were observed regardless of ARB and for all types of cancer, although conclusions regarding cause and effect cannot be established.

Based on the results of the Sipahi study, the FDA initiated a safety review of ARBs.Citation59 In July 2010, the FDA issued a communication stating that their results to date indicated that the benefits of ARB therapy outweighed the risks. The FDA did not conclude that ARBs increase the risk of cancer but they will continue their analysis and update the public as more data become available.

Safety of aliskiren

The clinical studies conducted to date with aliskiren have shown this agent to be well tolerated with an AE profile similar to that of placebo, although the treatment duration has been too short to evaluate potential risk for myocardial infarction or cancer. The most commonly reported AEs were fatigue, headache, dizziness, diarrhea, nasopharyngitis, and back pain.Citation15 Because aliskiren does not inhibit or induce cytochrome P450 isoenzymes, it has relatively few interactions with other drugs.Citation15 Aliskiren is contraindicated for women who are pregnant or may become pregnant because of the risk of fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality associated with drugs that act on the RAS.Citation60

To evaluate the safety and tolerability of aliskiren, White and colleagues pooled safety data from 12 randomized clinical trials of aliskiren involving 12,188 patients with hypertension.Citation16 The studies included in this analysis were categorized as short term (8 weeks) placebo controlled or long term (26–52 weeks) active controlled. In the short-term studies (n = 8862), AEs were reported by 33.6%, 31.6%, and 36.8% of patients treated with aliskiren 150 mg, aliskiren 300 mg, and placebo, respectively. Serious AEs occurred in 0.4%, 0.5%, and 0.7% of patients treated with aliskiren 150 mg, aliskiren 300 mg, and placebo, respectively. The rate of discontinuation due to AEs was ≤ 1.4% for both aliskiren doses and 2.6% for placebo. In the long-term studies (n = 3326), AEs were reported by 33.7% of patients treated with aliskiren 150 mg, 43.2% of patients treated with aliskiren 300 mg, 60.1% of patients treated with ACE inhibitors, 53.9% of patients treated with ARBs, and 48.9% of patients treated with thiazide diuretics. Serious AEs occurred in 3.4% of patients treated with aliskiren (both doses), compared with 2.4%, 8.4%, and 1.7% of patients treated with ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and thiazide diuretics, respectively. The rate of discontinuation due to AEs was 3.2%, 1.7%, 6.9%, 6.5%, and 3.3% for the aliskiren 150-mg, aliskiren 300-mg, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and thiazide diuretics groups, respectively. Incidences of AEs of special interest (possibly related to RAS agents) are listed in . The incidence of cough was low for all aliskiren treatment groups; it was similar to that of placebo in the short-term studies and lower than ACE inhibitors in the long-term studies. In the short-term studies, the incidence of abnormalities in prespecified laboratory values was low and similar to placebo. In the aliskiren 150-mg, aliskiren 300-mg, and placebo groups, respectively, 0.9%, 1.6%, and 1.3% of patients had serum potassium levels >5.5 mEq/L at any visit during the double-blind treatment period. In the long-term studies, 5.7% of patients treated with aliskiren 300 mg had serum potassium levels >5.5 mEq/L, compared with 1.9% to 3.7% of patients in all other treatment groups. Overall, the safety profile of aliskiren was similar to that of placebo and similar or superior to other antihypertensive agents.Citation16

Table 6 Adverse events of special interest from randomized controlled trials of aliskiren

Conclusions

ARBs are well tolerated, with a class safety profile similar to that of placebo and no known class-specific AEs. Results from meta-analyses evaluating the risks of myocardial infarction or cancer associated with ARBs have been inconsistent, and caution should be used when evaluating the results of these analyses because even the most well designed and carefully executed meta-analyses have significant limitations. Evidence from landmark, randomized clinical trials published to date does not suggest a link between ARBs and an increased risk of cancer or myocardial infarction. The FDA’s position on ARB use is that the benefits of these drugs outweigh their risks, and the FDA has not concluded that ARBs increase the risk of cancer. The DRI aliskiren is also a well-tolerated antihypertensive drug, with a safety profile that is similar to that of placebo and similar or superior to those of other antihypertensive drugs. As part of the aliskiren ASPIRE HIGHER clinical trials program, studies are ongoing in patients with known cardiovascular or renal risk factors and results of these trials will provide additional data on the overall tolerability profile of aliskiren.Citation1

Acknowledgements

Technical assistance with editing, figure preparation and styling of the manuscript for submission was provided by Cherie Koch, PhD, and Michael S. McNamara, MS, of Oxford PharmaGenesis Inc., and was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. The author was fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions and received no financial support or other form of compensation related to the development of this manuscript. The opinions expressed in the manuscript are those of the author and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation had no influence on the contents.

Disclosure

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- FogariRZoppiANew class of agents for treatment of hypertension: focus on direct renin inhibitionVasc Health Risk Manag2010686988220957132

- SeverPSGradmanAHAziziMManaging cardiovascular and renal risk: the potential of direct renin inhibitionJ Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst2009102657619502253

- VolpeMSavoiaCDe PaolisPOstrowskaBTarasiDRubattuSThe renin-angiotensin system as a risk factor and therapeutic target for cardiovascular and renal diseaseJ Am Soc Nephrol200213Suppl 3S173S17812466309

- GullapalliNBlochMJBasileJRenin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade in high-risk hypertensive patients: current approaches and future trendsTher Adv Cardiovasc Dis20104635937320965951

- ChobanianAVBakrisGLBlackHRSeventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood PressureHypertension20034261206125214656957

- KarlbergBECough and inhibition of the renin-angiotensin systemJ Hypertens199311Suppl 3S49S52

- DicpinigaitisPVAngiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelinesChest20061291 Suppl169S173S16428706

- SicaDABlackHRAngioedema in heart failure: occurrence with ACE inhibitors and safety of angiotensin receptor blocker therapyCongest Heart Fail20028633434134512461324

- GrossmanEMesserliFHGoldbourtUAntihypertensive therapy and the risk of malignanciesEur Heart J200122151343135211465967

- FriisSSorensenHTMellemkjaerLAngiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and the risk of cancer: a population-based cohort study in DenmarkCancer20019292462247011745304

- VerdecchiaPAngeliFRepaciSMazzottaGGentileGReboldiGComparative assessment of angiotensin receptor blockers in different clinical settingsVasc Health Risk Manag2009593994819997575

- StraussMHHallASAngiotensin receptor blockers may increase risk of myocardial infarction: unraveling the ARB-MI paradoxCirculation2006114883885416923768

- SipahiIDebanneSMRowlandDYSimonDIFangJCAngiotensin-receptor blockade and risk of cancer: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsLancet Oncol201011762763620542468

- VermaSStraussMAngiotensin receptor blockers and myocardial infarctionBMJ200432974771248124915564232

- SanoskiCAAliskiren: an oral direct renin inhibitor for the treatment of hypertensionPharmacotherapy200929219321219170589

- WhiteWBBresalierRKaplanAPSafety and tolerability of the direct renin inhibitor aliskiren: a pooled analysis of clinical experience in more than 12,000 patients with hypertensionJ Clin Hypertens (Greenwich)2010121076577521029339

- BezenconOBurDWellerTDesign and preparation of potent, nonpeptidic, bioavailable renin inhibitorsJ Med Chem200952123689370219358611

- TiceCMXuZYuanJDesign and optimization of renin inhibitors: Orally bioavailable alkyl aminesBioorg Med Chem Lett200919133541354519457666

- FyhrquistFSaijonmaaORenin-angiotensin system revisitedJ Intern Med2008264322423618793332

- SiragyHMComparing angiotensin II receptor blockers on benefits beyond blood pressureAdv Ther201027525728420524096

- ZhengZShiHJiaJLiDLinSA systematic review and meta-analysis of aliskiren and angiotension receptor blockers in the management of essential hypertensionJ Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst2010118 [Epub ahead of print].

- ParvingHHPerssonFLewisJBLewisEJHollenbergNKAliskiren combined with losartan in type 2 diabetes and nephropathyN Engl J Med2008358232433244618525041

- McMurrayJJPittBLatiniREffects of the oral direct renin inhibitor aliskiren in patients with symptomatic heart failureCirc Heart Fail20081172419808266

- SolomonSDAppelbaumEManningWJEffect of the direct renin inhibitor aliskiren, the angiotensin receptor blocker losartan, or both, on left ventricular mass in patients with hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophyCirculation2009119453053719153265

- SolomonSDHeeSSShahAEffect of the direct renin inhibitor aliskiren on left ventricular remodelling following myocardial infarction with systolic dysfunctionEur Heart J2011 [Epub ahead of print].

- MazzolaiLBurnierMComparative safety and tolerability of angiotensin II receptor antagonistsDrug Saf1999211233310433351

- Cozaar® (losartan potassium tablets) [prescribing information]2006Merck and Co., IncWhitehouse Station, NJ

- Diovan® (valsartan) Tablets [prescribing information]2008Novartis Pharmaceuticals CorporationEast Hanover, NJ

- JuliusSKjeldsenSEWeberMOutcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trialLancet200436394262022203115207952

- McMurrayJAngiotensin receptor blockers and myocardial infarction: analysis of evidence is incomplete and inaccurateBMJ20053307502126915920134

- OpieLHAngiotensin receptor blockers and myocardial infarction: direct comparative studies are neededBMJ200533075021270127115920136

- LewisEJAngiotensin receptor blockers and myocardial infarction: results reflect different cardiovascular states in patients with types 1 and 2 diabetesBMJ200533075021269127015920133

- TsuyukiRTMcDonaldMAAngiotensin receptor blockers do not increase risk of myocardial infarctionCirculation2006114885586016923769

- YousefZRLeyvaFGibbsCAngiotensin receptor blockers and myocardial infarction: cautions voiced are biologically credibleBMJ200533075021270127115920135

- VerdecchiaPAngeliFGattobigioRReboldiGPDo angiotensin II receptor blockers increase the risk of myocardial infarction?Eur Heart J200526222381238616081468

- McDonaldMASimpsonSHEzekowitzJAGyenesGTsuyukiRTAngiotensin receptor blockers and risk of myocardial infarction: systematic reviewBMJ2005331752187316183653

- VolpeMManciaGTrimarcoBAngiotensin II receptor blockers and myocardial infarction: deeds and misdeedsJ Hypertens200523122113211816269950

- CheungBMCheungGTLauderIJLauCPKumanaCRMeta-analysis of large outcome trials of angiotensin receptor blockers in hypertensionJ Hum Hypertens2006201374316121197

- MesserliFHBangaloreSRuschitzkaFAngiotensin receptor blockers: baseline therapy in hypertension?Eur Heart J200930202427243019723696

- WalkerEHernandezAVKattanMWMeta-analysis: Its strengths and limitationsCleve Clin J Med200875643143918595551

- SuzukiHKannoYEffects of candesartan on cardiovascular outcomes in Japanese hypertensive patientsHypertens Res200528430731416138560

- YusufSTeoKKPogueJTelmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular eventsN Engl J Med2008358151547155918378520

- YusufSTeoKAndersonCEffects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trialLancet200837296441174118318757085

- McMurrayJJHolmanRRHaffnerSMEffect of valsartan on the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular eventsN Engl J Med2010362161477149020228403

- SawadaTYamadaHDahlöfBMatsubaraHEffects of valsartan on morbidity and mortality in uncontrolled hypertensive patients with high cardiovascular risks: KYOTO HEART StudyEur Heart J200930202461246919723695

- MochizukiSDahlofBShimizuMValsartan in a Japanese population with hypertension and other cardiovascular disease (Jikei Heart Study): a randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint morbidity-mortality studyLancet200736995711431143917467513

- MassieBMCarsonPEMcMurrayJJIrbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fractionN Engl J Med2008359232456246719001508

- YusufSDienerHCSaccoRLTelmisartan to prevent recurrent stroke and cardiovascular eventsN Engl J Med2008359121225123718753639

- CohnJNTognoniGA randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failureN Engl J Med2001345231667167511759645

- SchraderJLudersSKulschewskiAMorbidity and Mortality After Stroke, Eprosartan Compared with Nitrendipine for Secondary Prevention: principal results of a prospective randomized controlled study (MOSES)Stroke20053661218122615879332

- GoldsteinMRMascitelliLPezzettaFAngiotensin-receptor blockade, cancer, and concernsLancet Oncol201011981781820816375

- KanehiraTTaniTTakagiTNakanoYHowardEFTamuraMAngiotensin II type 2 receptor gene deficiency attenuates susceptibility to tobacco-specific nitrosamine-induced lung tumorigenesis: involvement of transforming growth factor-b-dependent cell growth attenuationCancer Res200565177660766516140932

- ClereNCorreIFaureSDef iciency or blockade of angiotensin II type 2 receptor delays tumorigenesis by inhibiting malignant cell proliferation and angiogenesisInt J Cancer2010127102279229120143398

- MeredithPAMcInnesGTAngiotensin-receptor blockade, cancer, and concernsLancet Oncol201011981920816377

- LithellHHanssonLSkoogIThe Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE): principal results of a randomized double-blind intervention trialJ Hypertens200321587588612714861

- BangaloreSKumarSKjeldsenSEAntihypertensive drugs and risk of cancer: network meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of 324,168 participants from randomised trialsLancet Oncol2011121658221123111

- The ARB Trialists CollaborationEffects of telmisartan, irbesartan, valsartan, candesartan, and losartan on cancers in 15 trials enrolling 138 769 individualsJ Hypertens201129462363521358417

- HuangCCChanWLChenYCAngiotensin II receptor blockers and risk of cancer in patients with systemic hypertensionAm J Cardiol201110771028103321256465

- FDA Drug Safety CommunicationOngoing safety review of the angiotensin receptor blockers and cancer2010 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformation-forPatientsandProviders/ucm218845.htm. Accessed March 2011.

- Tekturna® (aliskiren) Tablets, Oral [prescribing information]2010Novartis Pharmaceuticals CorporationEast Hanover, NJ

- Atacand® (candesartan cilexetil) Tablets [prescribing information]2009AstraZeneca LPWilmington, DE

- Avapro® (irbesartan) Tablets [prescribing information]2007Bristol Myers Squibb Sanofi-Synthelabo PartnershipNew York, NY

- Micardis® (telmisartan) Tablets [prescribing information]2009Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.Ridgefield, CT

- Teveten® (eprosartan mesylate) Tablets [prescribing information]2007Abbott LaboratoriesNorth Chicago, IL

- Benicar® (olmesartan medoxomil) Tablets [prescribing information]2009Daiichi Sankyo, Inc.Parsippany, NJ

- SolomonSDWangDFinnPEffect of candesartan on cause-specific mortality in heart failure patients: the Candesartan in Heart failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) programCirculation2004110152180218315466644

- PfefferMASwedbergKGrangerCBEffects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programmeLancet2003362938675976613678868

- McMurrayJJOstergrenJSwedbergKEffects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function taking angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Added trialLancet2003362938676777113678869

- GrangerCBMcMurrayJJYusufSEffects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trialLancet2003362938677277613678870

- YusufSPfefferMASwedbergKEffects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved TrialLancet2003362938677778113678871

- PfefferMAMcMurrayJJVelazquezEJValsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or bothN Engl J Med2003349201893190614610160

- McMurrayJSolomonSPieperKThe effect of valsartan, captopril, or both on atherosclerotic events after acute myocardial infarction: an analysis of the Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial (VALIANT)J Am Coll Cardiol200647472673316487836

- DahlöfBDevereuxRBKjeldsenSECardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenololLancet20023599311995100311937178

- DicksteinKKjekshusJEffects of losartan and captopril on mortality and morbidity in high-risk patients after acute myocardial infarction: the OPTIMAAL randomised trial. Optimal Trial in Myocardial Infarction with Angiotensin II Antagonist LosartanLancet2002360933575276012241832

- BerlTHunsickerLGLewisJBCardiovascular outcomes in the Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial of patients with type 2 diabetes and overt nephropathyAnn Intern Med2003138754254912667024

- BrennerBMCooperMEde ZeeuwDEffects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathyN Engl J Med20013451286186911565518

- PittBPoole-WilsonPASegalREffect of losartan compared with captopril on mortality in patients with symptomatic heart failure: randomised trial--the Losartan Heart Failure Survival Study ELITE IILancet200035592151582158710821361