Abstract

Background and purpose

Despite the availability of risk engines to determine cardiovascular risk, risk factor control is suboptimal. Using EURIKA data we compared risk factor control in Germany with that of 11 other European countries (rest of Europe [ROE]) to identify differences and opportunities for improvement.

Methods

EURIKA was a multinational, cross-sectional study in 12 European countries including Germany from May 2009 to January 2010. Physicians’ attitudes to risk factor control based on the 2007 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention in a representative cohort of 7641 primary care outpatients aged ≥50 years with no CV disease and at least one major CV risk factor were determined.

Results

Compared to the ROE, German physicians were more frequently male (72.7% vs 62.6%), had a higher mean age (51.7 ± 8.4 vs 47.0 ± 9.7 years), faced higher patient loads (37.9% vs 16.5% had >199 patients/week), and involved other health sector professionals (dieticians, psychologists) less (31.8% vs 41.0% in the ROE). The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on CVD prevention were more important for German physicians (60.6% vs 55.9%), while those who didn’t use them gave reasons for nonuse as too many (62.5% vs 46.2%), too confusing, unrealistic, or not applicable to their patients. Risk engines were used less (54.5% vs 70.7%), with perceived lack of time (65.5% vs 60.2%) a frequent reason for nonuse. Risk factor control in German patients was inadequate (control rates: hypertension 36.3%, dyslipidemia 30.4%, type 2 diabetes 40.6%, obesity 28.8%) but largely comparable to other ROE countries; however, physicians tended to overestimate control rates.

Conclusion

EURIKA provides comprehensive data on the status of primary prevention of CVD in clinical practice in Germany and reveals considerable potential for improving the primary prevention of CVD.

Keywords:

Introduction

Cardiovascular (CV) risk factor assessment is crucial in refining diagnosis and tailoring treatment. When multiple risk factors have to be considered, the implications are more complex, because of their interrelationships and their less than additive impact on morbidity. To overcome this barrier, risk engines have been developed based on data from epidemiological studies, which consider multiple concurrent risk factors to come to an absolute risk estimate. Risk engines are also used to determine the impact of treatment on risk. Respective guidance has been laid down in major guidelines such as the European Society of Cardiology’s (ESC) Guideline on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice, the Guideline for the Management of Arterial Hypertension, and the Adult Treatment Panel III.Citation1–Citation3

Given this degree of elaborated evidence and guidance, it may be perceived as a surprise that cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors are largely uncontrolled in clinical practice, as documented in registries such as REACH or EUROASPIRE.Citation4,Citation5 Although a previous edition of the European guidelines recommended calculation of CVD risk with the SCORE, there has been no comprehensive assessment of the extent of use of formal risk assessment systems, the selection of risk assessment tools and the use of such estimates by physicians in clinical decision-making.Citation6,Citation7 Evidence is limited to less comprehensive surveys, usually limited to selected risk factors, or confined to a single country.Citation8–Citation12

In order to gain insight into the situation in Europe, including the attitude of physicians towards clinical guidelines for CVD prevention, cardiovascular risk assessment tools, and patient management, the European Study on Cardiovascular Risk Prevention and Management in Usual Daily Practice (EURIKA; NCT00882336) was conducted.Citation13–Citation17 The availability of this dataset provides a unique opportunity to compare the German data with a number of other European countries; to identify differences and opportunities to improve CVD prevention.

Methods

EURIKA was a multinational, cross-sectional study conducted in 12 European countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Norway, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and the UK) from May 2009 to January 2010. All participating patients provided written informed consent. The study design was published by Rodriguez-Artalejo et al and the EURIKA Investigators, and complies with local regulations for clinical research and was approved by the appropriate clinical research ethics committee in each participating country – which corresponded to the Ethics Committee of the Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany.Citation13

Physician and patient selection

Primary care physicians, cardiologists, endocrinologists, diabetes specialists, and internal medicine specialists were selected at random to represent practitioners involved in CVD prevention in primary care centers or outpatient clinics in each country using the OneKey database.Citation18 OneKey, a large database containing information on the demographics and specialties of physicians in each country, obtains information from directories of health centers, and is drawn from official web sources, registries, and addresses of health administrations and professional organizations in the public and private sectors, to make up the physicians panel or universe of doctors potentially participating in the study. This database lists 74,963 eligible physicians for Germany.

The selection criteria for patients were those aged ≥50 years who were free from clinical CVD, with at least one of the classic CVD risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, obesity, or tobacco consumption documented in the clinical record). Physicians received a randomization list to select a sample of patients cited for medical visits each day during the study period.

Variables collected

Information was collected at two levels. At the physician level, each physician answered a questionnaire regarding typical daily practice and opinions about cardiovascular risk management guidelines and global risk assessment tools. A patient-specific questionnaire captured information from clinical records and patients’ interviews regarding sociodemographic data, CVD risk factors, current medications, comorbidity, and other aspects of CVD prevention and management. Anthropometry and blood pressure (BP) readings were obtained under standardized conditions for each patient. Further, a fasting blood sample was obtained on the same day as the outpatient consultation or, if this was not possible, the following day. The blood samples were sent to a central laboratory in Belgium (Bio Analytical Research Corporation, Ghent, Belgium) for assessment of serum lipids, apo AI, apo B, hs-CRP, uric acid, HbA1c, and creatinine.

A 10% random sample of all centers with participating physicians underwent a site visit for data monitoring and audit to ensure data quality.

Treatment goals for CVD risk factors

Treatment goals were evaluated in accordance with European guidelines, based on data from either the physical examination or the blood sample drawn at the study visit.Citation1,Citation2 Target BP was systolic/diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP) <140/90 mm Hg, except for patients with diabetes where it was <130/80 mm Hg. Target lipid levels were <5 mmol/L (190 mg/dL) total cholesterol and <3 mmol/L (115 mg/dL) LDL-cholesterol, except for patients with diabetes where the goal was <4.5 mmol/L (175 mg/dL) total cholesterol, and <2.5 mmol/L (100 mg/dL) LDL-cholesterol. The target HbA1c was <6.5%, and the target fasting plasma glucose (FPG) was <6.1 mmol/L (110 mg/dL) in all patients. The target body mass index (BMI) was <30 kg/m2 and the target waist circumference (WC) was <102 cm in men and <88 cm in women.

We calculated the 10-year risk of fatal CVD for each patient using the SCORE equation, based on age, sex, current smoking, total cholesterol, and SBP measured at the study visit. These values were independent of treatment. We used the equation developed for low-risk regions for patients in Belgium, France, Greece, Spain, and Switzerland, and the equation for high-risk regions for patients in Austria, Germany, Norway, Russia, Sweden, Turkey, and the UK.Citation2,Citation4,Citation19,Citation20 A 10-year risk of CVD death ≥5% was regarded as high.Citation2,Citation21

Statistical analysis

Responses were collated and statistical analysis performed using SAS software (v 9.1; SAS Institute Corp, Cary, NC). The descriptive analysis contained statistical indicators as follows: qualitative variables were described by number of observed values (N), absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies per class, and percentage confidence intervals using SAS surveyfreq procedure. Patients with missing data were not included in the percentage calculation and the number of missing values was specified. Quantitative variables were described by number of observed values (N), arithmetic mean and confidence interval, sample standard deviation (SD), median, minimum and maximum, number of missing values using SAS survey means procedure. The number of out-of-range values was specified if applicable.

Results

Overall, 806 physicians participated in EURIKA, 66 of whom were located in Germany and 740 in the rest of the 11 European countries (the ROE). These physicians documented the clinical risk profile of 7641 patients (678 in Germany and 6963 in the ROE). Physician response rate was 8.0% in Germany (7.0% in the ROE, excluding Russia, where physician and patient response was 100%) and patient response rate was 49.0% (60.6% in the ROE, excluding Russia).

Physicians’ attitudes toward risk factor control

Out of a total of 66 physicians recruited in Germany, 48 were male (72.7%) and 25 physicians were aged <50 years (37.9%) (). Compared to other participating countries, German physicians were more frequently male and had a higher age (in the ROE, 62.6% were male, and 58.8% were aged <50 years). The number of physicians working together was smaller (<5 physicians) in Germany (68.2% vs 44.5% in the ROE), but the number of patients treated per week was substantially higher in Germany than in the ROE (37.9% vs 16.5% treated >199 patients per week).

Table 1 Physician demographics

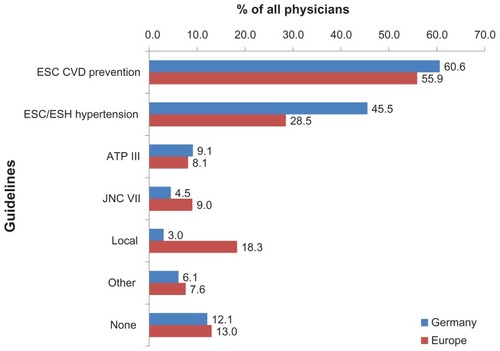

Overall, 87.9% of physicians in Germany (58/66) reported that they followed European guidelines on the treatment of cardiovascular risk factors, which was approximately comparable with other European countries (87.4%; 647/740) (guidelines specified in ). German physicians usually referred to the ESC Guideline on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice, and the ESC Guideline for the Management of Arterial Hypertension, while there was substantial use of localized guidelines in other countries (3.0% in Germany vs 18.3% in the ROE).Citation1,Citation2 Out of about 12% of physicians who indicated they did not use the guidelines (), 62.5% of those in Germany indicated that there are too many guidelines, a view shared by fewer physicians in other countries (46.2% in the ROE). In these countries, a lack of knowledge (29.0%), confusion over how to use the guidelines (9.7%), and a view that the guidelines were unrealistic (19.4%) were important reasons given for nonuse.

Figure 1 Physicians’ use of guidelines for the management of cardiovascular risk factors.

Table 2 Physicians’ reasons for not using clinical guidelines and global risk assessment tools, and beliefs about the limitations of risk assessment tools

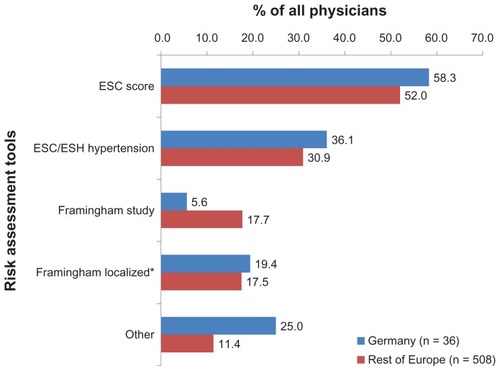

Physicians were also asked whether they routinely used global risk assessment tools to calculate cardiovascular risk in their patients, to which 54.5% in Germany (70.7% in the ROE) responded that they did. The most commonly used risk engines were the ESC SCORE, followed by algorithms outlined in the ESH/ESC hypertension guidelines (). Major differences between Germany and the ROE were found in the use of the original Framingham score (Germany < the ROE). The most common reasons given for not using scores were time constraints followed by little value, and a lack of knowledge on how to use them.

Figure 2 Physicians’ use of global risk assessment tools (of those using these tools).

Patient characteristics and degree of risk factor control

A total of 678 patients were recruited in Germany, in which the mean age was 65.3 ± 8.9 years, and in which 49.1% were male. On average, patients were slightly older than in the ROE (63.0 ± 8.9 years) and substantially more patients were aged at least 65 years (54.4% vs 39.5%). Frequent comorbid risk factors of the participating German patients were hypertension (81.0%), dyslipidemia (59.6%), obesity (49.0%), and diabetes mellitus (37.8%), of which hypertension, obesity, and diabetes mellitus were more common than in the ROE at 71.9%, 43.0%, and 25.7%, respectively. Overall, 57.1% of German patients (while only 38.4% in the ROE) were considered to be at high cardiovascular risk based on a SCORE total of ≥5% ().

Table 3 Sociodemographic and clinical patient characteristics

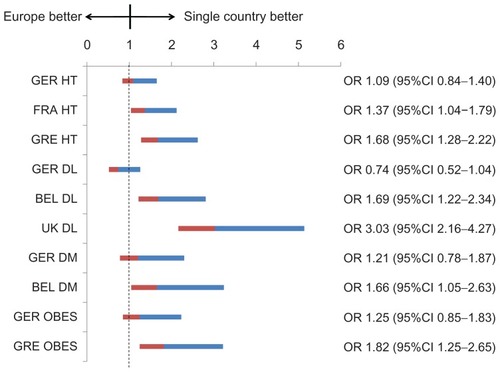

Actual German control rates of the main risk factors were 36.3% for hypertension, 30.4% for dyslipidemia (total cholesterol and LDL-c), 40.6% for type-2 diabetes (HbA1c), and 28.8% for obesity (based on BMI). Although there were only a few statistically significant differences in control rates between Germany and the ROE (), the control of dyslipidemia was worse in Germany (odds ratio [OR]: 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.52–1.04). By contrast, the control of dyslipidemia was particularly good in the UK (OR: 3.60; 95% CI: 2.16–4.27), and Belgium (OR: 1.69; 95% CI: 1.22–2.34). Countries with particularly good control of hypertension (France and Greece) used more angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB: 54.4%/59.1% vs 32.2% in Germany), fewer beta blockers (26.5%/23.5% vs 53.9%), and fewer ACE inhibitors (16.4%/25.4% vs 47.0%). In Belgium, where control of blood glucose was particularly effective, there was a pronounced use of metformin in comparison to Germany (69.4% vs 55.9%). Gross differences in the use of lipid-lowering drugs were not found, although control rates were higher in Belgium and the UK. Overall, there was a trend to overestimate control rates among physicians in participating countries.

Figure 3 Control of treated hypertension (<140/90 mm Hg), dyslipidemia (total cholesterol < 5 and LDL-c < 3 mmol/L),* type 2 diabetes (HbA1c < 6.5%), and obesity (BMI < 30 kg/m2) in special countries versus the average control rate in all countries.

Abbreviations: BEL, Belgium; FRA, France; GER, Germany; GRE, Greece; UK, United Kingdom; DL, dyslipidemia; DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension; OBES, obesity.

Perspectives to improve care

Physician-derived tips on how to improve behavioral risk factors are displayed in . Of particular concern to German physicians was that they need to spend more time with the patient (83.3% vs 74.1%), which was confirmed in strong recommendations to develop a sympathetic alliance with the patient, and to listen carefully. This was also directly related to patient load, which was substantially higher in Germany than in the ROE (37.9% vs 16.5% of physicians see more than 199 patients per week).

Table 4 Communication tips usually used for the management of behavioral risk factors (physicians)

On the other hand, German physicians tended to involve others less. While they had a strong preference for specific patient courses (42.4% vs 21.5%), they were less likely to involve nurses (21.2% vs 33.2%) or other health care staff (dieticians, social workers, psychologists) (31.8% vs 41.0%) than colleagues in the ROE.

Discussion

Taken together, the present analysis of CVD prevention and management strategies for at-risk patients in Germany demonstrates the high degree of unmet medical need and a lack of control. Key findings were: (1) physicians in Germany were more frequently older males working in private practice, facing a higher patient load. They were less likely to involve other health care staff in their patient management. (2) The ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention were more important for German physicians than other local documents, and those not referring to the guidelines gave reasons for nonuse as being that the guidelines were too numerous, were partially confusing, or even unrealistic and/or not applicable to their patients’ specific situations. Risk engines are used, although a perceived lack of time was a frequent reason given for their nonuse. (3) Risk factor control was inadequate but largely comparable with the mean of other countries; however, physicians tended to overestimate control rates. (4) Population risk for CVD mortality in Germany was attributed to diabetes and hypertension more frequently than in other countries.

Workload of German physicians

Out of a total of 806 physicians in EURIKA, 147 reported treating >199 patients per week (18.2%). This finding is in line with previous research documenting a mean workload of up to 73 patients per day.Citation22 This is of particular concern, since workload has been identified as a main barrier for more vigorously pursued CVD prevention.Citation23,Citation24 It is also worrisome because “time constraints” was among the most important reasons for not using guidelines or global risk assessment tools in the present survey. It was further determined in an Irish survey that the number of elderly patients was considered to be a major factor in determining workload, something that must be seriously considered given the ongoing demographic change in Germany.Citation25 High workload is also a major determinant of dissatisfaction among primary care physicians.Citation26

So what can be done?

(1) A recent study which aimed at determining the optimal size of practices in order to balance both physician workload and quality of care provided, demonstrated that the optimum average physician workload was found in the largest practices. Citation27 This may favor increasing the number of physicians in a single practice, which was lower in Germany in EURIKA (68.2% in Germany vs 44.5% in the ROE who reported having <5 colleagues in their work setting). (2) Use of disease management programs (DMPs) has been shown to decrease workload and increase practice satisfaction while improving the quality of care provided in primary care practices in 13 urban counties in California.Citation28 DMPs have already been installed in Germany for selected indications, and recent reports have shown improved health care processes and risk factor control in diabetic patients.Citation19,Citation20 Miksch et al have even suggested reduced mortality rates for diabetic patients enrolled in DMPs, but were cautious in claiming a causal relationship.Citation29

Useful guidance for clinical practice and use of risk engines

Guidelines are usually prepared by specialists in the field, and aim to mirror current evidence to the best possible extent. They further aim at being exhaustive, making them a proper reference for specialized physicians. Given these complexities, it is not surprising to find that translation of guidelines into primary care practice might be insufficient. For example, the German follow-up of the Hypertension Evaluation Project clearly demonstrated inadequate knowledge of the diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension.Citation30 Further, there is evidence that deficiencies in treatment quality appear to be the result of inadequate implementation of existing cardiologic treatment recommendations (among other factors).Citation21,Citation31 On the other hand, the results of a recent survey indicated that there is essentially no difference in the treatment provided by physicians knowledgeable in the guidelines and those who were less familiar.Citation11

Against a background of these considerations, it appears noteworthy that 87.9% of all physicians interviewed in Germany for the present survey reported following guidelines on the treatment of cardiovascular risk factors. This was about comparable with other European countries. On the other hand, while self-indicating a fairly good control of risk factors, a maximum of 40% of patients were actually controlled when hypertension, dyslipidemia, type-2 diabetes, and obesity were considered. This is in agreement with the aforementioned, giving rise to speculation that the guidelines might have to be more directive instead of targeting evidence completeness.

The same considerations may apply to the use of risk engines in clinical practice. In previous evaluations, for example, CHD risk in a population with diabetes was underestimated by the Framingham and UKPDS risk functions.Citation32–Citation34 Previous research also showed an overestimation of CHD risk predicted by the UKPDS risk function during 5 years of follow-up, the SCORE risk function during 10 years of follow-up, and the Framingham risk function in European populations.Citation35–Citation38 This was reflected in EURIKA by a number of physicians considering the “risk assessment tools to be of little use” (31.0% in Germany vs 20.9% in the ROE).

On the other hand, even among those who considered risk engines to be useful, there was a belief that “risk assessment tools have limitations” (79.7% in Germany vs 71.7% in the ROE) and the perception that engines “miss important risk factors” (83.0% in Germany vs 92.9% in the ROE) and do “not allow calculation of risk in the elderly” (80.0% in Germany vs 67.5% in the ROE). It essentially reflects that physicians feel that the results are of little use in their daily clinical practice. It appears difficult to tell which steps must be taken to improve the acceptance of these risk engines, but a local validation and the demonstration that risk scores may actually help in refining and improving therapies and outcomes in particular would certainly be of help. However, these data are scarce.

Risk factor control is inadequate

EURIKA has documented a largely inadequate control of risk factors in Germany, thus resembling previous reports on insufficient control rates of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity.Citation39–Citation41 Additionally, control is no better (but also no worse) compared with the average of the 11 other European EURIKA countries.

However, a closer look reveals that countries such as France, Greece, Belgium, and the UK do better in the control of single risk factors, while others are worse (Russia, Sweden, and Turkey). From a patient perspective, differences in age (54.4% vs 39.5% were aged at least 65 years in Germany) and gender (although substantially less likely at 49.1% vs 48.3% in ROE) may result in differences in control rates, due to advanced disease or different treatment patterns. Patients in Russia, Turkey, and Austria are considerably younger (at 58.3 years, 59.4 years, and 61.9 years, respectively), while in other countries such as Greece, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK, the patients are as old as those in Germany (65.3%).Citation14 Furthermore, patients in Russia were much less likely to be male (31.8%), while a substantial proportion in France were (54.8%).Citation14 These differences in sociodemographic characteristics are, however, not uniform and require further exploration of differences between countries which may explain these surprising findings.

Amongst these, the control of dyslipidemia in the UK is particularly noteworthy (OR: 3.03; 95% CI: 2.16–4.27): compared to the ROE, dyslipidemia control rate in Germany is rather poor (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.52–1.04). The study delivered two possible explanations for this finding: the percentage of German dyslipidemia patients receiving lipid-lowering drug treatment is smaller than in the ROE (65% vs 75%), and newer statins such as atorvastatin or rosuvastatin are prescribed less for German patients. On the other hand, however, the UK is the only country where simvastatin is available at a low 10 mg dose without prescription (over the counter, OTC).Citation42 It has been suggested that while it may not actually increase OTC use by patients themselves, it may have resulted in an overall increase in statin prescription rates by GPs in the UK.Citation43

Furthermore, hypertension control rates are above average in France (OR: 1.37; 95% CI: 1.04–1.79) and Greece (OR: 1.68; 95% CI: 1.28–2.22). We found ARB use was particularly high, and beta blocker and ACE inhibitor use was low in these countries. Based on these data, it is uncertain whether or not this may actually lead to a causal improvement in blood pressure control, but ARBs have been associated with a particularly high rate of treatment compliance and long-term blood pressure control in comparison with beta blockers, for example.Citation44

Limitations

The lack of a comprehensive framework for physician sampling in all European countries might be perceived as a potential limitation of the EURIKA study. We used the best available approximation – the OneKey database – which is the largest available database of practicing physicians in Europe, although it is not statistically representative of all European physicians. Further, the participation rate among invited physicians was not optimal, which may have resulted in a bias towards physicians being more involved in CVD prevention, suggesting that results obtained might represent a best-case scenario that might slightly overestimate the control of CVD risk factors and quality of care in usual clinical practice.

On the other hand, the large number of participating practitioners, coverage of major medical specialties and work-settings, and random selection of patients, suggests that the EURIKA study makes an important contribution to the identification of barriers in the diagnosis and management of cardiovascular disease, and is as accurate as practically possible.

Conclusion

EURIKA provides comprehensive data on the situation of primary prevention of CVD in clinical practice in Germany. It reveals a considerable potential for improving the primary prevention of CVD. Our data suggest that (1) a way to reduce patient load must be found, (2) guidelines including those for CVD prevention must be tailored to meet the need of primary care physicians, in order to increase guideline acceptance in clinical practice, and (3) differences in performance between countries may point towards determinants important for increased risk factor control.

Authors’ contributions

Dr Bramlage drafted the manuscript and requested further analyses. Professor Schmieder and Dr Goebel revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Steering board of the EURIKA study

Fernando Rodriguez Artelajo and José Ramon Banegas (chairmen), Madrid, Spain; Philippe Gabriel Steg (chairman), Paris, France; Julian Halcox, Cardiff, UK; Jean Dallongeville, Lille, France; Claudio Borghi, Bologna, Italy; Joep Perk, Oskarshamn, Sweden; Guy de Backer, Gent, Belgium; Eliseo Guallar, Baltimore, MD; Elvira L Massó González (MCMD delegate), Madrid, Spain.

Acknowledgments

The EURIKA study was funded by AstraZeneca. The study was conducted by an independent academic steering committee (see below).

Disclosure

Roland E Schmieder and Peter Bramlage report that they received research support from AstraZeneca. Professor Schmieder further reports to have received honoraria from AstraZeneca for talks. Matthias Goebel is an employee of AstraZeneca, the sponsor of this study.

References

- GrahamIAtarDBorch-JohnsenKEuropean Society of Cardiology (ESC); European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (EACPR); Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; European Association for Study of Diabetes (EASD); International Diabetes Federation Europe (IDF-Europe); European Stroke Initiative (EUSI); Society of Behavioural Medicine (ISBM); European Society of Hypertension (ESH); WONCA Europe (European Society of General Practice/Family Medicine); European Heart Network (EHN); European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS)European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: full text. Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts)Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil.200714Suppl 2S111317726407

- ManciaGDe BackerGDominiczakAThe Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension, The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Eur Heart J200728121462153617562668

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP), Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III)Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final reportCirculation2002106253143342112485966

- BhattDLStegPGOhmanEMREACH Registry InvestigatorsInternational prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosisJAMA2006295218018916403930

- KotsevaKWoodDDe BackerGDe BacquerDPyoralaKKeilUEUROASPIRE Study GroupEUROASPIRE III: a survey on the lifestyle, risk factors and use of cardioprotective drug therapies in coronary patients from 22 European countriesEur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil200916212113719287307

- De BackerGAmbrosioniEBorch-JohnsenKThird Joint Task Force of the European and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical PracticeEuropean guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Third Joint Task Force of European and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical PracticeEur Heart J200324171601161012964575

- ConroyRMPyoralaKFitzgeraldAPSCORE Project GroupEstimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE projectEur Heart J20032411987100312788299

- HobbsFDErhardtLAcceptance of guideline recommendations and perceived implementation of coronary heart disease prevention among primary care physicians in five European countries: the Reassessing European Attitudes about Cardiovascular Treatment (REACT) surveyFam Pract200219659660412429661

- GrahamIMStewartMHertogMGCardiovascular Round Table Task ForceFactors impeding the implementation of cardiovascular prevention guidelines: findings from a survey conducted by the European Society of CardiologyEur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil200613583984517001227

- ErhardtLRHobbsFDA global survey of physicians’ perceptions on cholesterol management: the From The Heart studyInt J Clin Pract20076171078108517577295

- BramlagePThoenesMKirchWLenfantCClinical practice and recent recommendations in hypertension management – reporting a gap in a global survey of 1259 primary care physicians in 17 countriesCurr Med Res Opin200723478379117407635

- CelentanoAPanicoSPalmieriVCitizens and family doctors facing awareness and management of traditional cardiovascular risk factors: results from the Global Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Project (Help Your Heart Stay Young Study)Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis200313421121714650353

- Rodriguez-ArtalejoFGuallarEBorghiCEURIKA InvestigatorsRationale and methods of the European Study on Cardiovascular Risk Prevention and Management in Daily Practice (EURIKA)BMC Public Health20101038220591142

- BanegasJRLopez-GarciaEDallongevilleJAchievement of treatment goals for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice across Europe: the EURIKA studyEur Heart J201132172143215221471134

- DallongevilleJBanegasJRTubachFSurvey of physicians’ practices in the control of cardiovascular risk factors: the EURIKA studyEur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil2011Epub Apr18

- GuallarEBanegasJRBlasco-ColmenaresEExcess risk attributable to traditional cardiovascular risk factors in clinical practice settings across Europe – The EURIKA StudyBMC Public Health20111170421923932

- BanegasJRLopez-GarciaEDallongevilleJAchievement of lipoprotein goals among patients with metabolic syndrome at high cardiovascular risk across Europe. The EURIKA studyInt J Cardiol2011Epub Nov4

- OneKey databaseBensheim: Cegedim Deutschland GmbHnd Available from http://crm.cegedim.com/country/germany/En/DataOptimization/OneKey/Pages/default.aspxAccessed March 8, 2012

- StarkRGSchunkMVMeisingerCRathmannWLeidlRHolleRHORA Study GroupMedical care of type 2 diabetes in German disease management programs: a population-based evaluationDiabetes Metab Res Rev201127438339121308948

- BestehornKJannowitzCKarmannBPittrowDKirchWCharacteristics, management and attainment of lipid target levels in diabetic and cardiac patients enrolled in Disease Management Program versus those in routine care: LUTZ registryBMC Public Health2009928019653899

- PruggerCHeuschmannPUKeilUEpidemiology of hypertension in Germany and worldwideHerz2006314287293 German16810468

- WittchenHUKrausePHoflerMAim, design and methods of the “Hypertension and diabetes screening and awareness” – (HYDRA) studyFortschritte der Medizin2003121Suppl 1211 German14732944

- JohanssonHStenlundHLundstromLWeinehallLReorientation to more health promotion in health services – a study of barriers and possibilities from the perspective of health professionalsJ Multidiscip Healthc2010321322421289862

- WensingMVan den HomberghPVan DoremalenJGrolRSzecsenyiJGeneral practitioners’ workload associated to practice size rather than chronic care organisationHealth Policy200989112412918599149

- CullenWGroganLO’ConnorEBuryG“Why are we working so hard?” A cross-sectional survey of factors influencing GP workload in the Eastern Regional Health Authority areaIr Med J200295720921221412227528

- WhalleyDBojkeCGravelleHSibbaldBGP job satisfaction in view of contract reform: a national surveyBr J Gen Pract200656523879216464320

- WensingMvan den HomberghPAkkermansRvan DoremalenJGrolRPhysician workload in primary care: what is the optimal size of practices? A cross-sectional studyHealth Policy200677326026716129508

- FernandezAGrumbachKVranizanKOsmondDHBindmanABPrimary care physicians’ experience with disease management programsJ Gen Intern Med200116316316711318911

- MikschALauxGOseDIs there a survival benefit within a German primary care-based disease management program?Am J Manag Care2010161495420148605

- HagemeisterJSchneiderCABarabasSHypertension guidelines and their limitations – the impact of physicians’ compliance as evaluated by guideline awarenessJ Hypertens200119112079208611677375

- BabergHTYazarABrechmannTHealth care quality: medication and prevention in patients with and without coronary heart diseaseMed Klin (Munich)200499116 German14716479

- ColemanRLStevensRJRetnakaranRHolmanRRFramingham, SCORE, and DECODE risk equations do not provide reliable cardiovascular risk estimates in type 2 diabetesDiabetes Care20073051292129317290036

- McEwanPWilliamsJEGriffithsJDEvaluating the performance of the Framingham risk equations in a population with diabetesDiabet Med200421431832315049932

- GuzderRNGatlingWMulleeMAMehtaRLByrneCDPrognostic value of the Framingham cardiovascular risk equation and the UKPDS risk engine for coronary heart disease in newly diagnosed Type 2 diabetes: results from a United Kingdom studyDiabet Med200522555456215842509

- YangXSoWYKongAPDevelopment and validation of a total coronary heart disease risk score in type 2 diabetes mellitusAm J Cardiol2008101559660118308005

- UlmerHKolleritsBKelleherCDiemGConcinHPredictive accuracy of the SCORE risk function for cardiovascular disease in clinical practice: a prospective evaluation of 44,649 Austrian men and womenEur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil200512543344116210929

- Bastuji-GarinSDeverlyAMoyseDIntervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment Study GroupThe Framingham prediction rule is not valid in a European population of treated hypertensive patientsJ Hypertens200220101973198012359975

- BrindlePEmbersonJLampeFPredictive accuracy of the Framingham coronary risk score in British men: prospective cohort studyBMJ20033277426126714644971

- SharmaAMWittchenHUKirchWHYDRA Study GroupHigh prevalence and poor control of hypertension in primary care: cross-sectional studyJ Hypertens200422347948615076152

- BohlerSGlaesmerHPittrowDDiabetes and cardiovascular risk evaluation and management in primary care: progress and unresolved issues – rationale for a nationwide primary care project in GermanyExp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes2004112415717015127318

- HaunerHBramlagePLoschCPrevalence of obesity in primary care using different anthropometric measures – results of the German Metabolic and Cardiovascular Risk Project (GEMCAS)BMC Public Health2008828218694486

- StewartDCunninghamITHansfordDJohnDMcCaigDMcLayJGeneral practitioners’ views and experiences of over-the-counter simvastatin in ScotlandBr J Clin Pharmacol201070335635920716235

- FilionKBDelaneyJABrophyJMErnstPSuissaSThe impact of over-the-counter simvastatin on the number of statin prescriptions in the United Kingdom: a view from the General Practice Research DatabasePharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf20071611416953516

- BramlagePHasfordJBlood pressure reduction, persistence and costs in the evaluation of antihypertensive drug treatment – a reviewCardiovasc Diabetol200981819327149

- ChobanianAVBakrisGLBlackHRNational Heart, Lung, and Blood Insitute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating CommitteeThe Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 ReportJAMA2003289192560257212748199