Abstract

Stress-induced cardiomyopathy (SIC), also known as Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, is characterized by severe but potentially reversible regional left ventricular wall motion abnormalities, ie, akinesia, in the absence of explanatory angiographic evidence of a coronary occlusion. The typical pattern is that of an akinetic apex with preserved contractions in the base, but other variants are also common, including basal or midmyocardial akinesia with preserved apical function. The pathophysiology of SIC remains largely unknown but catecholamines are believed to play a pivotal role. The diverse array of triggering events that have been linked to SIC are arbitrarily categorized as either emotional or somatic stressors. These categories can be considered as different elements of a continuous spectrum, linked through the interface of neurology and psychiatry. This paper reviews our current knowledge of SIC, with focus on the intimate relationship between the brain and the heart.

Introduction

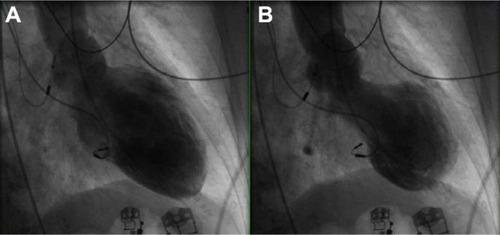

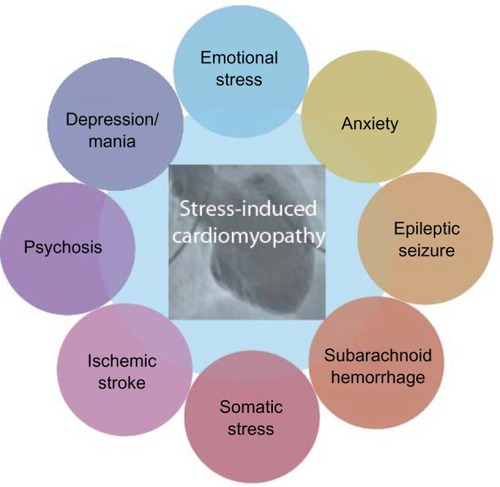

Stress-induced cardiomyopathy (SIC), also known as Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, broken heart syndrome, ampulla cardiomyopathy, and apical ballooning syndrome, was first recognized in Japan almost twenty years ago. Since then, more than 1500 reports on the subject have been published, and an increasing amount of articles are published each year.Citation1 Approximately 90% of reported SIC patients were women.Citation1,Citation2 As the name of this syndrome implies, a preceding somatic and/or emotional stressor can be identified in a majority of the patients ().Citation1,Citation3 Since its recognition, SIC has emerged as a rather common entity and is an important differential diagnosis in patients with chest pain. The characteristic hallmark is potentially reversible regional left-ventricular wall motion abnormality, ie, akinesia, in the absence of explanatory angiographic evidence of a coronary occlusion.Citation4 The typical pattern is that of an akinetic apex with preserved contractions in the base (), but other variants are also common, including basal or midmyocardial akinesia with preserved apical function.Citation1 SIC is associated with electrocardiogram (ECG) changes indicative of ischemia and elevated plasma levels of cardiac proteins. Although several attempts have been made to distinguish between SIC and acute myocardial infarction, based on noninvasive diagnostic criteria, as of yet, these two conditions can only reliably be distinguished by invasive procedures, ie, absence of explanatory coronary lesions on the angiogram.Citation5,Citation6 The etiology, epidemiology, and pathophysiology of SIC remain largely unknown, but catecholamines are believed to play a pivotal role. Among the evidence suggesting an important role of catecholamines in the pathophysiology of SIC is the observation that plasma catecholamine levels are severely elevated in these patients, and SIC is common in patients with pheochromocytoma.Citation7,Citation8 In addition, iatrogenically administered beta-adrenoceptor agonists have been documented to trigger episodes.Citation4 Last but not least, we and others have provoked SIC-like cardiac dysfunction in rats by exogenous administration of catecholamines.Citation9,Citation10

Figure 1 Midventricular variant of stress-induced cardiomyopathy. End-diastolic (A) and end-systolic (B) images of the left ventricle, obtained during ventriculography, in a patient with chest pain.

Table 1 Preceding somatic or emotional stressors in the development of stress-induced cardiomyopathy

The short- and long-term prognoses of SIC patients were initially believed to be excellent, but recent reports indicate that SIC may be associated with significant mortalityCitation11–Citation14 Data from Sahlgrenska University Hospital indicate a significant mortality in patients with SIC.Citation14

Definition of SIC

One potential reason for underestimating the severity of the disease relates to the Mayo criteria which are often used to diagnose SIC ().Citation3

Table 2 Myoclinic criteria and Gothenburg criteria in the diagnosis of stress-induced cardiomyopathy

In fact, when these interim criteria were first presented, the authors insightfully pointed out that the criteria would need to be revised in accordance with the growing knowledge about SIC.Citation3 There is now considerable evidence for concomitant coronary artery disease and SIC.Citation15–Citation17 Strict adherence to the above criteria excludes all patients with significant coronary artery disease. Furthermore, any patient that dies acutely in SIC, by definition, cannot have “transient ventricular dysfunction” and may therefore not be diagnosed with SIC. Indeed, many publications have used “reversible cardiac dysfunction” as an inclusion criterion. The Mayo criteria may thus lead to an underestimation of the severity of this disease. Furthermore, if SIC is indeed mediated by stress-induced catecholamine toxicity,Citation18,Citation19 there is no good reason to exclude patients with pheochromocytoma. Instead, SIC should be recognized as a potential complication in these patients. There have been attempts at redefining these diagnostic criteria.Citation17

Data from our hospital indicate a significant mortality in patients with SIC, and we have previously suggested the Gothenburg criteria for diagnosing SIC ().Citation14 These criteria pertain to patients that survive the acute phase of SIC. Additional histological criteria for diagnosing SIC in patients who do not survive the acute phase would be desirable. Taken together, these clinical and histological criteria would allow for better design of clinical studies regarding SIC.

Cardiac manifestations

SIC typically presents as left-ventricular apical akinesia and systolic ballooning with preserved or hyperdynamic basal function. This pattern is reported in >85% of all patients described in the literature. However, other types are increasingly being reported.Citation1 It remains to be established whether the typical variant is the predominant type of stress-induced cardiac dysfunction or if it is simply more easily detected. It is possible that other types of SIC, as well as milder forms of “apical ballooning,” occur without being recognized in the population. With so many preceding events described to trigger SIC, it is possible that different degrees of transient SIC-like cardiac dysfunction may be rather common in the general population. In severe SIC cases, more than 2/3 of the left ventricle may be affected, and such extensive cardiac dysfunction frequently leads to potentially fatal complications, including cardiogenic shock, ventricular rupture, ventricular fibrillation, and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. However, observations from Sahlgrenska University Hospital indicate that in contrast to acute myocardial infarction, left-ventricular filling pressures are normal or near normal in SIC patients. Furthermore, cardiac dysfunction is completely or almost completely reversible if the patient survives the acute phase. In fact, cardiac function typically normalizes within a few days or weeks.Citation14

Beyond adrenergic overstimulation, our understanding of the pathophysiology underlying the cardiac dysfunction is limited. Among the proposed hypotheses are coronary artery spasm, microvascular dysfunction, outflow tract obstruction, and direct effects of catecholamine on the myocardium.Citation20 One hypothesis postulates that regional contractile dysfunction is protective, rather than detrimental, in the setting of severe myocardial catecholamine overstimulation.Citation20 Perhaps even more intriguing than the development of this peculiar type of extensive cardiac dysfunction, is the apparently complete recovery observed in most patients. Elucidation of the self-healing mechanisms, at the cellular and at the systemic level, behind the recovery could have implications across the spectrum of cardiovascular disease.

SIC beyond the heart

It is not unusual for a SIC patient to survive an episode in which the akinesia involves > 50% of the left ventricle. In the setting of acute myocardial infarction, loss of function of that magnitude would most likely result in death.Citation21 Such a contradictory finding highlights the enigmatic nature of SIC. We hypothesized that compensatory cardiocirculatory mechanisms are activated to maintain sufficient perfusion of the vital organs in this setting and showed that SIC was associated with decreased sympathetic tone, decreased peripheral vascular resistance, and preserved cardiac output.Citation14 These findings differ from that observed in acute myocardial infarction and would be consistent with our observation of near-normal filling pressures in SIC. Indeed, if one considers that one distinctive hallmark of SIC appears to be severely elevated plasma levels of catecholamines, it may be reasonable to view SIC as a condition that is associated with cardiac as well as extracardiac changes. In addition to its unique cardiocirculatory profile, SIC may be intimately linked to other organ systems. In the remainder of this manuscript we turn our attention to the close relationship between the brain and the heart, in SIC.

SIC and the brain

The common denominator for the different factors shown to trigger SIC appears to be the activation of the sympatico-adrenal system. Although the many triggering events described to date are diverse, they can be arbitrarily divided into two categories, namely, emotional and somatic stressors; these categories can be considered as different elements of a continuous spectrum, linked through the interface of neurology and psychiatry ().

Figure 2 Connection between stress-induced cardiomyopathy (SIC) and neuropsychiatry.

Indeed, cardiac protein release and reversible left-ventricular dysfunction are common in patients with an acute intracranial episode.Citation22–Citation24

Several recent case reports have highlighted the connection between subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and SIC.Citation25,Citation26 Similar degenerative postmortem histological findings were seen in the hearts of SAH patients, as in patients with SIC and pheochromocytoma.Citation7,Citation27 Consistent with observations in the general SIC cohort, among patients that presented with SAH, release of cardiospecific proteins was much more common in women. Furthermore, in a multivariate analysis that also included ejection fraction, cardiac protein release was associated with lower systolic blood pressure.Citation22

Much like SAH, ischemic stroke is intimately linked to SIC.Citation28 Elevated plasma levels of cardiac proteins are present in almost 20% of these patients, and cardiac protein release is associated with poor prognosis.Citation29 In a recent report that included 569 patients with ischemic stroke and that used apical akinesia as an obligate criterion, SIC occurred in 1.2% (n = 7), all of whom were women.Citation28 Cardiac function recovered within 3 weeks. The reader should note that restricting the diagnosis of SIC to patients presenting with the typical apical variant may have caused the authors to underestimate the prevalence of SIC in these patients. There exists a two-way relationship between ischemic stroke and SIC, in the sense that ischemic stroke may be either the cause or the consequence of SIC.Citation30–Citation32 Although thrombus formation may occur rather frequently within the akinetic left ventricle, thromboembolic complications appear to be less common.Citation33 Short-term antithrombotic therapy should, nevertheless, be considered in SIC patients, especially in those patients that present with the typical apical variant.Citation33,Citation34

The third group of intracranial events that has been documented to trigger SIC is epileptic seizures. Also, these patients display the SIC phenotype, with left ventricular apical akinesia and typical patchy myocardial lesions.Citation35 Similar to the situation in patients with SAH and ischemic stroke, as well as in the general SIC cohort, women are overrepresented among epileptic patients that develop SIC.Citation36 The finding that SIC secondary to epilepsy appears to be particularly associated with more severe complications has led some authors to speculate that SIC may explain some cases of unexpected sudden death in epilepsy.Citation36 We don’t believe it to be a great leap to go from the intimate relationship between SIC and acute lesions of higher cerebral centers, including the insular area,Citation28 to the relationship between SIC and emotional stressors.

The fact that acute severe emotional stress can trigger SIC has been known since the syndrome was first described, and this observation led to the coining of the terms “stress-induced cardiomyopathy” and “broken heart syndrome.” Two recent extensive overviews of American SIC cohorts found that anxiety and chronic stress were both associated with significantly higher odds of developing SIC.Citation2,Citation37 Also, depression was associated with near-significantly increased odds of developing SIC.Citation2 This is consistent with a previous report that found an increased prevalence of premorbid psychiatric diagnoses, particularly anxiety disorders, in SIC patients.Citation38 These findings are intriguing, as they imply that chronic stress and impaired well-being may predispose an individual to develop SIC. If this is indeed the case, it adds to the evidence that SIC spans the domains of psychiatric as well as somatic medicine, highlighting the inherent link between the two. One survey found that almost 16% of postmenopausal women reported significant depressive symptoms and that depressive symptoms were associated with cardiovascular events.Citation39 Again, this is the typical SIC patient category. Indeed, chronic stress and depression have both been shown to cause structural changes to the cerebrum, including decreased volume of the hippocampus and loss of grey matter in the prefrontal and cingulate cortices. Furthermore, these structural changes have been linked to alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to stress.Citation40 We believe that SIC may occur acutely in biologically predisposed individuals in response to an acute stressor and that this biological predisposition may, in turn, be caused by chronic stress or impaired well-being.

Psychiatric conditions may not only predispose an individual to develop SIC in response to a strong emotional and/or somatic stressor, there have been published reports describing exacerbations of psychiatric illnesses that have, in themselves, acutely triggered SIC.Citation41

We propose that SIC be viewed as a cardiocirculatory syndrome that is intimately linked to other organs, perhaps most importantly the brain. Because SIC is a potential complication of, among others, neurological and psychiatric conditions, we believe that increased awareness of the syndrome is desirable, not only among cardiologists but also among other specialists. Although the treatment of SIC is the task of the cardiologist, successful prevention, and to some extent, early detection, may sometimes lie in the hands of other physicians.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ShaoYRedforsBLyonARRosengrenASwedbergKOmerovicETrends in publications on stress-induced cardiomyopathyInt J Cardiol2012157343543622521379

- DeshmukhAKumarGPantSRihalCMurugiahKMehtaJLPrevalence of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the United StatesAm Heart J20121641667122795284

- PrasadALermanARihalCSApical ballooning syndrome (Tako-Tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarctionAm Heart J2008155340841718294473

- AbrahamJMuddJOKapurNKKleinKChampionHCWittsteinISStress cardiomyopathy after intravenous administration of cate-cholamines and beta-receptor agonistsJ Am Coll Cardiol200953151320132519358948

- JohnsonNPChavezJFMosleyWJ2ndFlahertyJDFoxJMPerformance of electrocardiographic criteria to differentiate Takotsubo cardiomyopathy from acute anterior ST elevation myocardial infarctionInt J Cardiol Epub7282011

- AhmedKAMadhavanMPrasadABrain natriuretic peptide in apical ballooning syndrome (Takotsubo/stress cardiomyopathy): comparison with acute myocardial infarctionCoron Artery Dis201223425926422395239

- WittsteinISThiemannDRLimaJANeurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stressN Engl J Med2005352653954815703419

- ParkJHKimKSSulJYPrevalence and patterns of left ventricular dysfunction in patients with pheochromocytomaJ Cardiovasc Ultrasound2011192768221860721

- ShaoYRedforsBScharin TängMNovel rat model reveals important roles of β-adrenoreceptors in stress-induced cardiomyopathyInt J Cardiol Epub1252013

- PaurHWrightPTSikkelMBHigh levels of circulating epinephrine trigger apical cardiodepression in a β2-adrenergic receptor/Gi-dependent manner: a new model of Takotsubo cardiomyopathyCirculation2012126669770622732314

- SharkeySWWindenburgDCLesserJRNatural history and expansive clinical profile of stress (tako-tsubo) cardiomyopathyJ Am Coll Cardiol201055433334120117439

- LeePHSongJKSunBJOutcomes of patients with stress-induced cardiomyopathy diagnosed by echocardiography in a tertiary referral hospitalJ Am Soc Echocardiogr201023776677120620862

- BurgdorfCKurowskiVBonnemeierHSchunkertHRadkePWLong-term prognosis of the transient left ventricular dysfunction syndrome (Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy): focus on malignanciesEur J Heart Fail200810101015101918692439

- SchultzTShaoYRedforsBStress-induced cardiomyopathy in Sweden: evidence for different ethnic predisposition and altered cardio-circulatory statusCardiology2012122318018622846788

- HaghiDPapavassiliuTHammKKadenJJBorggrefeMSuselbeckTCoronary artery disease in takotsubo cardiomyopathyCirc J20077171092109417587716

- KurisuSInoueIKawagoeTPrevalence of incidental coronary artery disease in tako-tsubo cardiomyopathyCoron Artery Dis200920321421819318927

- GaibazziNUgoFVignaliLZoniAReverberiCGherliTTako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy with coronary artery stenosis: a case-series challenging the original definitionInt J Cardiol2009133220521218313156

- AkashiYJNakazawaKSakakibaraMMiyakeFKoikeHSasakaKThe clinical features of takotsubo cardiomyopathyQJM200396856357312897341

- ParkJHKangSJSongJKLeft ventricular apical ballooning due to severe physical stress in patients admitted to the medical ICUChest2005128129630216002949

- LyonARReesPSPrasadSPoole-WilsonPAHardingSEStress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy – a novel pathophysiological hypothesis to explain catecholamine-induced acute myocardial stunningNat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med200851222918094670

- PageDLCaulfieldJBKastorJADeSanctisRWSandersCAMyocardial changes associated with cardiogenic shockNew Engl J Med197128531331375087702

- TungPKopelnikABankiNPredictors of neurocardiogenic injury after subarachnoid hemorrhageStroke200435254855114739408

- KonoTMoritaHKuroiwaTOnakaHTakatsukaHFujiwaraALeft ventricular wall motion abnormalities in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage – neurogenic stunned myocardiumJ Am Coll Cardiol19942436366408077532

- SimonRPAminoffMJBenowitzNLChanges in plasma catecholamines after tonic-clonic seizuresNeurology19843422552576538024

- EnnezatPVPesenti-RossiDAubertJMTransient left ventricular basal dysfunction without coronary stenosis in acute cerebral disorders: a novel heart syndrome (inverted Takotsubo)Echocardiography200522759960216060897

- DasMGonsalvesSSahaARossSWilliamsGAcute subarachnoid haemorrhage as a precipitant for takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a case report and discussionInt J Cardiol2009132228328518077020

- DoshiRNeil-DwyerGHypothalamic and myocardial lesions after subarachnoid haemorrhageJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry1977408821826925706

- YoshimuraSToyodaKOharaTTakotsubo cardiomyopathy in acute ischemic strokeAnn Neurol200864554755418688801

- KerrGRayGWuOStottDJLanghornePElevated troponin after stroke: a systematic reviewCerebrovasc Dis200928322022619571535

- ShinSNYunKHKoJSLeft ventricular thrombus associated with takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a cardioembolic cause of cerebral infarctionJ Cardiovasc Ultrasound201119315215522073327

- de GregorioCGrimaldiPLentiniCLeft ventricular thrombus formation and cardioembolic complications in patients with Takotsubo-like syndrome: a systematic reviewInt J Cardiol20081311182418692258

- LeurentGLarraldeABoulmierDCardiac MRI studies of transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome (takotsubo cardiomyopathy): a systematic reviewInt J Cardiol2009135214614919401260

- HaghiDPapavassiliuTHeggemannFKadenJJBorggrefeMSuselbeckTIncidence and clinical significance of left ventricular thrombus in tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy assessed with echocardiographyQJM2008101538138618334499

- JabaraRGadesamRPendvalaLChronosNKingSBChenJPComparison of the clinical characteristics of apical and non-apical variants of “broken heart” (takotsubo) syndrome in the United StatesJ Invasive Cardiol200921521622219411722

- ShimizuMKagawaATakanoTMasaiHMiwaYNeurogenic stunned myocardium associated with status epilepticus and postictal catecholamine surgeIntern Med200847426927318277028

- StöllbergerCWegnerCFinstererJSeizure-associated Takotsubo cardiomyopathyEpilepsia20115211e160e16721777230

- El-SayedAMBrinjikjiWSalkaSDemographic and co-morbid predictors of stress (takotsubo) cardiomyopathyAm J Cardiol201211091368137222819424

- SummersMRLennonRJPrasadAPre-morbid psychiatric and cardiovascular diseases in apical ballooning syndrome (tako-tsubo/stress-induced cardiomyopathy): potential pre-disposing factors?J Am Coll Cardiol201055770070120170799

- Wassertheil-SmollerSShumakerSOckeneJDepression and cardiovascular sequelae in postmenopausal women. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI)Arch Intern Med2004164328929814769624

- GianarosPJJenningsJRSheuLKGreerPJKullerLHMatthewsKAProspective reports of chronic life stress predict decreased grey matter volume in the hippocampusNeuroimage200735279580317275340

- CorriganFE3rdKimmelMCJayaramGFour cases of takotsubo cardiomyopathy linked with exacerbations of psychiatric illnessInnov Clin Neurosci201187505321860845

- Elmir OmverovicHow to think about stress-induced cardiomyopathy? Think “out of the box”!Scand Cardiovasc J2011452677121401402