?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Background

Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular mortality, as it acts through its effects on target organs, such as the heart and kidneys. Hyperuricemia increases cardiovascular risk in patients with hypertension.

Objective

To assess the relationship between serum uric acid and target organ damage (left ventricular hypertrophy and microalbuminuria) in untreated patients with essential hypertension.

Patients and methods: A cross-sectional study was carried out in 130 (85 females, 45 males) newly diagnosed, untreated patients with essential hypertension. Sixty-five healthy age- and sex-matched non-hypertensive individuals served as controls for comparison. Left ventricular hypertrophy was evaluated by cardiac ultrasound scan, and microalbuminuria was assessed in an early morning midstream urine sample by immunoturbidimetry. Blood samples were collected for assessing uric acid levels.

Results

Mean serum uric acid was significantly higher among the patients with hypertension (379.7±109.2 μmol/L) than in the controls (296.9±89.8 μmol/L; P<0.001), and the prevalence of hyperuricemia was 46.9% among the hypertensive patients and 16.9% among the controls (P<0.001). Among the hypertensive patients, microalbuminuria was present in 54.1% of those with hyperuricemia and in 24.6% of those with normal uric acid levels (P=0.001). Similarly, left ventricular hypertrophy was more common in the hypertensive patients with hyperuricemia (70.5% versus 42.0%, respectively; P=0.001). There was a significant linear relationship between mean uric acid levels and the number of target organ damage (none versus one versus two: P=0.012).

Conclusion

These results indicate that serum uric acid is associated with target organ damage in patients with hypertension, even at the time of diagnosis; thus, it is a reliable marker of cardiovascular damage in our patient population.

Introduction

Hypertension is an important cardiovascular problem worldwide.Citation1 Its prevalence is increasing in developing countries.Citation2 Hypertension has adverse effects on various target organs, thus increasing the risk of stroke, coronary heart disease, and heart failure.Citation3 This leads to high morbidity and mortality in many cases. Elevated blood pressure (BP) is also associated with an accelerated rate of decline in cognitive and renal function.Citation3

In evaluating a patient with hypertension, it is recommended that target organ damage (TOD) be identified in order to better define the individual’s global cardiovascular risk in an effort to guide the decision to begin treatment, and to determine target BP levels.Citation2,Citation3 In less developed parts of the world, the diagnosis of hypertension is often delayed and, as a result, TOD may be present at the time of diagnosis.Citation4 Uric acid (UA) levels tend to be elevated in patients with hypertension.Citation5 Elevated UA is a risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease, and the European Society of Hypertension–European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend performing routine laboratory testing for serum UA (SUA) in patients with hypertension.Citation5,Citation6 While it has been shown that SUA is associated with multiple cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and renal disease, it remains to be known if UA independently predicts adverse cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension. Various large trials have failed to identify UA as a significant and independent risk factor.Citation7,Citation8

Identifying patients with subclinical TOD provides the best opportunity for preventing progression to overt cardiovascular disease. In clinical practice in limited-resource settings, it may not be practical to screen every newly diagnosed hypertensive individual for subclinical TOD due to limited access to facilities for echocardiography and microalbuminuria; therefore, identification of a relatively inexpensive risk marker, like UA, may help to identify patients who are at higher risk, thereby directing further evaluation.

This study was thus aimed at investigating the relationship between SUA and left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy and microalbuminuria in newly diagnosed, untreated patients with essential hypertension.

Patients and methods

Study design

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study carried out in the medical outpatient clinics of the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria.

Study population

A total of 130 consecutive, never-treated, newly diagnosed hypertensive subjects aged between 30–70 years of age were included in the study. The study population consisted of an ethnically diverse group of black Nigerians from Rivers State, and the neighboring south–south states of the Niger Delta, involved in the various economic activities in the area, mainly in the oil and gas sector.

The subjects were characterized by: 1) average clinic systolic BP (SBP) values >140 mmHg or diastolic BP (DBP) >90 mmHg, confirmed during two visits at the outpatient clinic; 2) no history or clinical evidence of congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, cardiac valve disease, coronary bypass surgery or angioplasty, diabetes mellitus and renal insufficiency, and no treatment with urate-lowering medication; and 3) no clinical evidence of secondary hypertension.

After informed written consent had been obtained, all patients returned to the clinic after an overnight fast and underwent the following procedures: 1) clinic BP measurement; 2) venous blood sample collection for SUA; 3) spot midstream urine collection for microalbuminuria (patients with proteinuria on dipstick testing were excluded); 4) transthoracic echocardiogram; and 5) routine investigations (serum creatinine, fasting lipid profile, and plasma glucose).

Sixty-five non-hypertensive, healthy age- and sex-matched individuals were randomly selected from the hospital staff and patients’ relatives and were classified as controls.

The Ethics Committee of the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital approved the study protocol.

Uric acid

UA was analyzed with the enzymatic colorimetric method using an autoanalyzer. Normal values in the hospital laboratory are <360 μmol/L and <420 μmol/L for women and men, respectively; therefore, individuals who had values above these levels were classified as having hyperuricemia.

Fasting lipid profile

Fasting cholesterol and triglyceride (TG) levels were measured using the enzymatic method with a reagent from Atlas Medical Laboratories (Atlas Development Corporation, Calabasas, CA, USA). Fasting high-density lipoprotein (HDL) was measured with the precipitation method. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol values were calculated using the Friedewald equation when the TG level was <4.0 mmol/L:Citation9

(1)

Definition of an abnormal lipid profile:Citation10

Elevated TG = TG >1.7 mmol/L.

Hypercholesterolemia = TC >5.2 mmol/L.

Low HDL cholesterol = HDL cholesterol <1.03 mmol/L.

Elevated LDL cholesterol = LDL cholesterol >3.0 mmol/L.

Microalbuminuria

Randox immunoturbidimetric assay for urinary albumin (Randox Laboratories, Antrim, UK) was used to determine microalbuminuria in an early morning spot midstream urine sample. Microalbuminuria was defined as an albumin concentration between 20–200 mg/L. This is equivalent to albumin excretion of 30–300 mg/24 hours (in a urine sample collected over 24 hours).Citation11

Blood pressure measurements

BP was measured with a standard (Accoson; AC Cossor and Son [Surgical] Ltd, Essex, UK) mercury sphygmomanometer (with an appropriate cuff size) on the patients’ right arm, as the patients were in the seated position with their feet on the floor after a 5-minute rest. SBP and DBP were taken at Korotkoff phases 1 and 5, respectively to the nearest 2 mmHg. The average of two BP measurements taken 5 minutes apart was used. The presence and severity of hypertension were then defined based on the seventh Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High BP guidelines.Citation1

Echocardiography

Echocardiographic studies for all the patients were carried out with an Aloka Prosound SSD 4000 echocardiography machine (Fair Medical Company Ltd, Matsudo, Japan) equipped with a 2.5 Hz transducer. With the patient in the left lateral decubitus position, targeted echocardiographic estimations were taken. These included the standard two-dimensional oriented motion–mode measurements of interventricular septal thickness in diastole, LV posterior wall thickness in diastole, and LV end diastolic diameter just beyond the tips of the mitral valve leaflets. LV mass (in grams) was automatically calculated with the internal software of the machine.

LV mass was indexed to the body surface area using cut-off values of 134 g/m2 and 110 g/m2 for men and women, respectively.Citation12

Relative wall thickness (RWT) was calculated as 2× posterior wall thickness in end diastole/LV end diastolic diameter. A partition value of 0.45 for RWT was used for both men and women.Citation13

Patients with increased LV mass index (LVMI) and increased RWT were considered to have concentric hypertrophy, and those with increased LVMI and normal RWT were considered to have eccentric hypertrophy. Those with normal LVMI and increased or normal RWT were considered to have concentric remodeling or normal geometry, respectively.

Definition of target organ damage

TOD was defined by the presence of microalbuminuria (urinary albumin excretion: 20–200 mg/L) or echocardiographic evidence of LV hypertrophy (LVH) defined as LVMI ≥134 g/m2 in men and ≥110 g/m2 in women.

Definition of degree of target organ damage

The degree was determined by the number of target organs involved (ie, 0= no TOD; 1 TOD = presence of either LVH or microalbuminuria; 2 TOD = presence of both LVH and microalbuminuria).Citation14

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using the commercially available Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0 analytic software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviations, and frequencies as a percentage. Continuous variables were compared with the Students t-test, or one-way analysis of variance, as considered appropriate. Proportions or categorical parameters were compared with the chi-square test. Relations among continuous variables were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient and multiple linear regression analysis. All tests were considered to be statistically significant at the P-value ≤0.05.

Results

There were 130 patients with a female-to-male ratio of 1.9:1. The age range was 31–70 years, with a mean age of 46.8±9.3 years. The age range of the controls was 31–70 years with a mean age of 44.4±9.8 years. There was no statistically significant difference in the mean ages of the cases and controls (P=0.094). The mean body mass index of the cases was 29.0±5.0 kg/m2, which was significantly higher than that of the controls (26.6±3.3 kg/m2; P=0.001). The baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics of the study population are shown in .

Table 1 Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the study population

LVH was present in 55.4% of the cases and in 10.8% of the controls (P<0.001), and the most common geometric pattern among the cases was concentric hypertrophy, while the majority of the controls had normal LV geometry. The prevalence of microalbuminuria among the cases was 37.7%, while it was 7.7% in the controls (P<0.001). Overall, 67% of the cases had at least one TOD, and females were more affected than males (P=0.045).

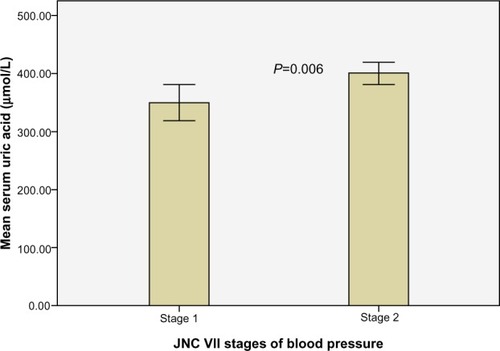

The mean SUA was significantly higher in the cases (379.7±109.2 μmol/L) than in the controls (296.9±89.8 μmol/L; P<0.001), and the prevalence of hyperuricemia was 46.9% among the cases and 16.9% among the controls (P<0.001). The mean SUA increased significantly with the severity of hypertension ().

Figure 1 Relationship between SUA and severity of hypertension.

Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SUA serum uric acid.

Microalbuminuria was present in 54.1% of the hypertensive cases with hyperuricemia, and in 24.6% of the cases with normal UA levels (P=0.001). Similarly LVH was more common among the hypertensive cases with hyperuricemia compared to the hypertensive cases with normal serum uric acid levels (70.5% versus 42.0% respectively, P=0.001). Among the eleven (16.9%) controls that had hyperuricemia, two had LVH and none had microalbuminuria. shows the clinical and laboratory characteristics of the 130 cases with and without elevated SUA.

Table 2 Anthropometric, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the 130 hypertensive cases with and without elevated SUA

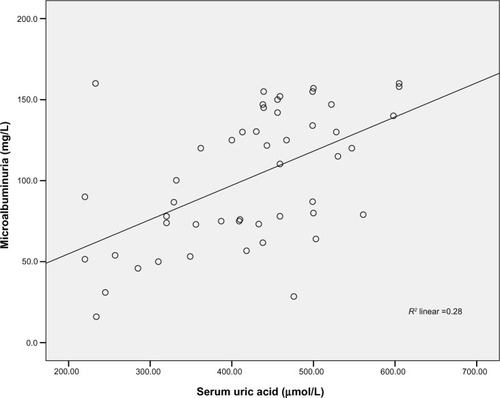

SUA correlated positively with microalbuminuria among the cases (r=0.529; P<0.001), suggesting that in those with microalbuminuria, urine albumin excretion increased with increasing levels of SUA (). This correlation remained significant even after controlling for the following variables: age (r=0.535; P<0.001); body mass index (BMI) (r=0.476; P=0.001); waist circumference (WC) (r=0.489; P<0.001); SBP (r=0.522; P<0.001); and DBP (r=0.537; P<0.001), respectively. The correlation was not significant among the controls (r=0.085; P=0.178). With multiple linear regression analysis, SUA was independently associated with microalbuminuria after adjusting for confounding variables including age, BMI, WC, SBP and DBP. The variables combined explained 31.1% of the variance observed (F=3.154; P=0.012). SUA made a statistically significant and unique contribution to the variance in microalbuminuria (β=0.517; P=0.001).

While the correlation between LVMI and SUA among the controls was not significant (r=0.169; P=0.500), it was positive and significant among the cases (r=0.336; P<0.001), with high levels of SUA associated with higher indexed LV mass. The correlation remained significant after controlling for age (r=0.332; P<0.001); BMI (r=0.303; P<0.001); WC (r=0.287; P<0.001); SBP (r=0.308; P<0.001); and DBP (r=0.328; P<0.001). SUA levels were also independently associated with LVMI in regression analysis after adjusting for confounders including age, BMI, WC, SBP, and DBP. The variables combined explained 25.4% of the variance observed in LVMI (P<0.001). SBP made the largest unique contribution (P=0.001), although SUA also made a statistically significant contribution (P=0.003).

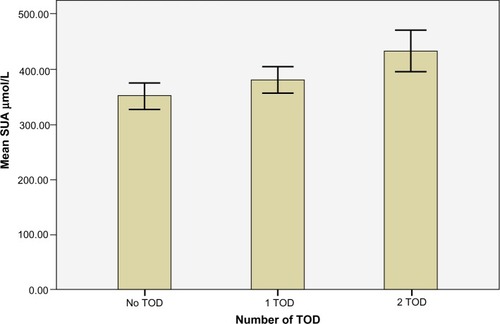

There was a significant positive correlation between SUA level and the number of target organs involved (r=0.255; P=0.017). This suggests that the number of TOD increased with increasing levels of SUA. shows that the mean SUA level was higher in the cases with both microalbuminuria and LVH (419.2±135.9 μmol/L), than in those with either of these indices of TOD alone (381.1±93.7 μmol/L), or in those with none (345.8±92.2 μmol/L). This was statistically significant (P=0.012).

Figure 3 Mean SUA levels analyzed based on the degree of TOD involvement.

Abbreviations: TOD, target organ damage; SUA, serum uric acid.

On further analysis, UA correlated significantly with other cardiovascular risk factors, as shown in .

Table 3 Pearson’s correlation coefficients of SUA and clinical variables

Discussion

The main findings in this study were that hyperuricemia was more prevalent among hypertensive individuals than among the normotensive controls, and elevated SUA in the patients with hypertension was accompanied by increased urinary albumin concentrations and increased LVMI. This was similar to the findings by Poudel et al,Citation15 who conducted a cross-sectional study of untreated hypertensive individuals in Nepal. It was found that hyperuricemia was more common among hypertensive patients when compared to the normotensive controls (28.8% versus 13.7%, respectively; P<0.001).Citation15 However, this prevalence was lower than the 46.9% rate found in the present study. This difference may be attributed to the higher BMI and SBP of the patients in this study. A retrospective study of 351 patients with essential hypertension in Northern Nigeria also concluded that hyperuricemia was more common among hypertensive patients compared to normotensive individuals.Citation16 In that population, there was a significant positive correlation between SUA and SBP and DBP. This is in contrast to our study where even though stage 2 (compared to stage 1) hypertension was associated with higher mean SUA, there was no significant correlation between SUA and SBP or DBP, respectively.

Another important finding in the present study was that hypertensive patients who had elevated UA levels had evidence of an increasing number of target organ involvement than those with UA levels in the normal range. Moreover, UA correlated significantly with other cardiovascular risk factors such as increased BMI, increased WC (which is a measure of visceral adiposity), and hypertriglyceridemia. This has also been shown in other studies.Citation17–Citation19 In an interesting commentary published in the Journal of Human Hypertension, ReynoldsCitation20 notes that UA can be considered one of the components of the metabolic syndrome, as various studies have shown its association with BP, obesity, TG, and HDL cholesterol.Citation21,Citation22 Although he correctly points out that correlation does not prove causation, a possible pathogenetic mechanism linking these associations includes the release of free fatty acids from visceral adipose tissue, which increases hepatic gluconeogenesis.Citation23 This reduces peripheral tissue glucose uptake, thus causing hyperinsulinemia. In turn, this causes avid renal salt retention, which drives up the BP, as well as increases urate reabsorption.Citation23 This state is also associated with the release of proinflammatory markers including fibrinogen and C-reactive protein, which all act in concert with dyslipidemia to increase the overall cardiovascular risk of an individual.Citation23 The significant positive correlation between microalbuminuria and SUA levels found in this study may be a result of the association between UA and risk factors for renal damage, like systolic hypertension and obesity, or due to their common link with the proinflammatory state.Citation24 This is supported by the recent findings of Dmitriev et al,Citation25 who studied 100 hypertensive patients at moderate and high risk for experiencing cardiovascular events. At SUA levels >319 μmol/L, the hypertensive patients were found to have microalbuminuria, as well as elevated C-reactive protein (a nonspecific marker of inflammation). The latter also correlated with SUA, especially in the patients at high risk.Citation25

The regression analysis in the present study showed that UA was a significant predictor of microalbuminuria, independent of SBP, which also contributed to the variance observed in microalbuminuria. Since one of the major sites of UA production in the cardiovascular system is the vessel wall, especially the endothelium, elevated UA may be a marker of endothelial dysfunction, and microalbuminuria is the renal manifestation of generalized endothelial dysfunction.Citation26 Laboratory testing for SUA in parts of Nigeria is cheaper and far more readily available than that for microalbuminuria, and it can be assessed even in primary care settings to identify hypertensive patients at higher cardiovascular risk.

Hypertension promotes renal dysfunction which, in turn, increases SUA and activates the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system; angiotensin II is essential in the development of LVH.Citation27 This may partly explain the observation in this study, that UA correlated significantly with LVMI and was a unique predictor of the variance in LV mass. This is consistent with the findings by Iwashima et al,Citation19 where UA not only correlated positively with LVMI, but it also predicted the risk for future cardiovascular events during the follow-up period. However, their study differs from this one in the sense that the patients had longstanding hypertension, and some of them were on diuretics and/or uricosuric agents. The positive correlation in their study persisted even after excluding the effects of drugs on UA levels.Citation19 On the other hand, Tsioufis et alCitation24 did not demonstrate a significant correlation between UA and LVMI in the recently diagnosed hypertensive patients in their study. In their entire study population, the mean duration of hypertension was 5.5 years, and LVMI was within the normal values. The majority (65%) of their patients were also on treatment for hypertension, although they had a 4-week washout period prior to participation in the study. These differences in patient characteristics may partly account for the disparate results.

In a more recent study by Yoshimura et alCitation28 of 1,943 hypertensive and normotensive subjects, the relationship between SUA and LVH was significant only among males and not females. Other studies have shown significant relationships among women only.Citation14,Citation29 These sex differences have been attributed to the differences in sex hormones, but they have not been unequivocally proven.Citation14 The link between UA and LV mass might relate to an association of UA with other risk factors, especially renal dysfunction, oxidative stress, severity of hypertension, and obesity.Citation19 Previous reports have shown that UA impaired nitric oxide generation and induced endothelial dysfunction and smooth muscle cell proliferation.Citation30 In experimental and in vitro systems, UA appears to have the ability to induce inflammatory mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor α, and mitogen-activated protein kinases, which are known to induce cardiac hypertrophy.Citation31 UA, by activating the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (both at the local and systemic levels), promotes cardiomyocyte growth and interstitial fibrosis, which are the pathologic hallmarks of LVH.Citation32 These discoveries suggest that cardiac hypertrophy may be, at least in part, attributable to an increase in UA itself, via the stimulation of endothelial dysfunction, smooth muscle cell proliferation, and inflammation. Lowering UA has been associated with modest benefits. The LIFE (Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction) studyCitation33 demonstrated a 29% reduction in composite cardiovascular outcome (stroke, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular deaths) in the losartan (an angiotensin receptor blocker) arm of the study, which was attributed to the uricosuric effect of losartan. A recent study demonstrated that in patients with ischemic heart disease, modest LVH regression followed the lowering of SUA with high-dose allopurinol.Citation34 However, as noted by Zoccali and Mallamaci,Citation35 this does not provide sufficient evidence that UA-lowering is the mechanism underlying the benefit of allopurinol and, by implication, other urate-lowering agents, as beyond lowering UA, the inhibition of xanthine oxidase leads to better endothelial responses and modulation of oxidative stress.

Furthermore, the elegant review by Feig et alCitation36 did not find sufficient evidence to conclude that treating asymptomatic hyperuricemia was beneficial, while noting that the adverse effects of a drug like allopurinol can prove fatal.

It was found in this study that SUA increased as the number of TOD went up from none to two. This was similar to the results obtained from 425 untreated essential hypertensive patients (who were a part of the large Microalbuminuria: A Genoa Investigation on Complications trial) where UA was significantly correlated with the presence and number of TOD.Citation14 The findings in this study were also in keeping with the results of a more recent study conducted by Şerban et al.Citation37 They found that SUA was significantly higher in hypertensive patients who had more than three indices of TOD compared to those with two or less. Carotid intima–media thickness – a surrogate marker of atherosclerosis – was found to correlate significantly with UA and microalbuminuria in their study. Their study population was, however, not limited to newly diagnosed hypertensive patients; therefore, the independent influence of the duration of hypertension on TOD cannot be ruled out.Citation37

The cases in the present study population were newly diagnosed and largely unaware of their BP status, yet a significant number had evidence of subclinical TOD, which has been shown to herald cardiovascular events.Citation38,Citation39 The significant associations found between SUA and TOD in this study thus suggests that UA is a robust marker for future cardiovascular events and, as such, should be routinely measured in hypertensive individuals as part of their initial cardiovascular work-up at the time of diagnosis.

Limitations of this study include the fact that it is cross-sectional, and thus no causal relationships can be inferred. The limited sample size with the participants recruited from a tertiary health center questions the generalizability of the findings to the average person in the community with hypertension.

The present study was not designed to establish causation; therefore, we cannot comment on the clinical utility of lowering UA to prevent TOD. To firmly establish the causal role of UA in the incidence of TOD among hypertensive patients, large cohort studies are needed. Furthermore a well-designed, randomized, controlled trial is needed to determine the clinical benefits of lowering UA in these patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is the opinion of the authors that in clinical practice in limited-resource settings, a cheap screening test like SUA should be done in all patients presenting with hypertension in order to identify those who are at higher total cardiovascular risk, and who thus warrant more intensive investigations and intervention.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ChobanianAVBakrisGLBlackHRJoint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood PressureNational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood PressureHypertension20034261206125214656957

- WhitworthJAWorld Health Organization, International Society of Hypertension Writing Group2003 World Health Organization (WHO)/ International Society of Hypertension (ISH) statement on management of hypertensionJ Hypertens200321111983199214597836

- British Cardiac Society; British Hypertension Society; Diabetes UK; HEART UK; Primary Care Cardiovascular Society; Stroke AssociationJBS 2: Joint British Societies’ guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practiceHeart200591Suppl 5v1v5216365341

- SalakoBLOgahOSAdebiyiAAUnexpectedly high prevalence of target-organ damage in newly diagnosed Nigerians with hypertensionCardiovasc J Afr2007182778317497043

- CannonPJStasonWBDemartiniFESommersSCLaraghJHHyperuricemia in primary and renal hypertensionN Engl J Med196627594574645917940

- European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology Guidelines Committee2003 European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertensionJ Hypertens20032161011105312777938

- CulletonBFLarsonMGKannelWBLevyDSerum uric acid and risk for cardiovascular disease and death: the Framingham Heart StudyAnn Intern Med1999131171310391820

- DuffyWBSenekjianHOKnightTFWeinmanEJManagement of asymptomatic hyperuricemiaJAMA198124619221522167289015

- FriedewaldWTLevyRIFredricksonDSEstimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifugeClin Chem19721864995024337382

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III)Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final reportCirculation2002106253143342112485966

- de JongPECurhanGCScreening, monitoring, and treatment of albuminuria: Public health perspectivesJ Am Soc Nephrol20061782120212616825331

- DevereuxRBDetection of left ventricular hypertrophy by M-mode echocardiography. Anatomic validation, standardization, and comparison to other methodsHypertension198792 Pt 2II19II262948914

- GanauADevereuxRBPickeringTGRelation of left ventricular hemodynamic load and contractile performance to left ventricular mass in hypertensionCirculation199081125362297829

- ViazziFParodiDLeonciniGSerum uric acid and target organ damage in primary hypertensionHypertension200545599199615781669

- PoudelBYadavBKKumarAJhaBRautKBSerum uric acid level in newly diagnosed essential hypertension in a Nepalese population: a hospital based cross sectional studyAsian Pac J Trop Biomed201441596424144132

- EmokpaeAMAbduASerum uric acid levels among Nigerians with essential hypertensionNiger J Physiol Sci2013281414423955405

- RussoCOlivieriOGirelliDGuariniPCorrocherRRelationships between serum uric acid and lipids in healthy subjectsPrev Med19962556116168888330

- NanHQiaoQDongYThe prevalence of hyperuricemia in a population of the coastal city of Qingdao, ChinaJ Rheumatol20063371346135016821269

- IwashimaYHorioTKamideKRakugiHOgiharaTKawanoYUric acid, left ventricular mass index, and risk of cardiovascular disease in essential hypertensionHypertension200647219520216380520

- ReynoldsTMSerum uric acid and new-onset hypertension: a possible therapeutic avenue?J Hum HypertensEpub 1162014

- SundstromJSullivanLD’AgostinoRBRelations of serum uric acid to longitudinal blood pressure tracking and hypertension incidenceHypertension200545283315569852

- TsouliSGLiberopoulosENMikhaildisDPElevated serum uric acid levels in metabolic syndrome: an active component or an innocent bystanderMetabolism2006551012931230116979398

- JohnsonRJKangDHFeigDIs there a pathogenetic role for uric acid in hypertension and cardiovascular and renal disease?Hypertension20034161183119012707287

- TsioufisCChatzisDVezaliEThe controversial role of serum uric acid in essential hypertension: relationships with indices of target organ damageJ Hum Hypertens200519321121715647779

- DmitrievVAOshchepkovaEVTitovBN[Is there an association of uric acid level with preclinical target organ damage in moderate-and high-risk hypertensive patients?]Ter Arkh20138595257 Russian24261230

- NiskanenLKLaaksonenDENyyssönenKUric acid level as a risk factor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in middle-aged men: a prospective cohort studyArch Intern Med2004164141546155115277287

- LorellBHCarabelloBALeft ventricular hypertrophy: pathogenesis, detection, and prognosisCirculation2000102447047910908222

- YoshimuraAAdachiHHiraiYSerum uric acid is associated with the left ventricular mass index in males of a general populationInt Heart J2014551657024463929

- MatsumuraKOhtsuboTOnikiHFujiiKIidaMGender-related association of serum uric acid and left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensionCirc J200670788588816799243

- RaoGNCorsonMABerkBCUric acid stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by increasing platelet-derived growth factor A-chain expressionJ Biol Chem199126613860486082022672

- YokoyamaTNakanoMBednarczykJLMcIntyreBWEntmanMMannDLTumor necrosis factor-alpha provokes a hypertrophic growth response in adult cardiac myocytesCirculation1997955124712529054856

- WatanabeSKangDHFengLUric acid, hominoid evolution, and the pathogenesis of salt-sensitivityHypertension200240335536012215479

- KjeldsenSEDahlöfBDevereuxRBLIFE (Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction) Study GroupEffects of losartan on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with isolated systolic hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy: a Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction (LIFE) substudyJAMA2002288121491149812243636

- RekhrajSGandySJSzwejkowskiBRHigh-dose allopurinol reduces left ventricular mass in patients with ischemic heart diseaseJ Am Coll Cardiol201361992693223449426

- ZoccaliCMallamaciFUric acid, hypertension, and cardiovascular and renal complicationsCurr Hypertens Rep201315653153724072559

- FeigDIKangDHJohnsonRJUric acid and cardiovascular riskN Engl J Med2008359171811182118946066

- ŞerbanCDrăganSChristodorescuRAssociation of serum uric levels and carotid intima thickness with the numbers of organ damaged in hypertensive patientsInternational Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine and Public Health201131816

- KlausenKPScharlingHJensenGNew Definition of Microalbuminuria in Hypertensive subjects: Association with Incident Coronary Heart Disease and DeathHypertension200546333715928029

- AgabitiREMuiesanMLPathophysiology and treatment of hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophyDialogues in Cardiovascular Medicine2005101318