Abstract

Stroke is the leading cause of disability in the USA and a major cause of mortality worldwide. One out of four strokes is recurrent. Secondary stroke prevention starts with deciphering the most likely stroke mechanism. In general, one of the main goals in stroke reduction is to control vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and smoking cessation. Changes in lifestyle like a healthy diet and aerobic exercise are also recommended strategies. In the case of cardioembolism due to atrial fibrillation, mechanical valves, or cardiac thrombus, anticoagulation is the mainstay of therapy. The role of anticoagulation is less evident in the case of bioprosthetic valves, patent foramen ovale, and dilated cardiomyopathy with low ejection fraction. Strokes due to larger artery atherosclerosis account for approximately a third of all strokes. In the case of symptomatic extracranial carotid stenosis, surgical intervention as close as possible in time to the index event seems highly beneficial. In the case of intracranial large artery atherosclerosis, the best medical therapy consists of antiplatelets, high-dose statins, aggressive controls of vascular risk factors, and lifestyle modifications, with no role for intracranial arterial stenting or angioplasty. For patients with small artery occlusion (ie, lacunar stroke), the therapy is similar to that used in patients with intracranial large artery atherosclerosis. Despite the constant new evidence on how to best treat patients who have suffered a stroke, the risk of stroke recurrence remains unacceptably high, thus evidencing the need for novel therapies.

Introduction

Stroke is defined as clinical, radiological, or pathological evidence of ischemia or hemorrhage, involving a defined cerebral vascular territory.Citation1 In the USA, there are approximately 800,000 strokes per year, approximately 600,000 of which are recurrent events. Stroke is now the fifth leading cause of death, but it remains the number one cause of disability in the USA.Citation2 While there has been a steady decline in stroke incidence in developed countries, incidence in low-to-middle-income countries continues to increase – accounting for 85% of the worldwide stroke burden.Citation3

Once a stroke has occurred, treatment options are limited and only available for a short time immediately after the symptom onset. As a result, stroke prevention has been considered the mainstay in stroke management for over half a century, and despite decades of research in stroke prevention, there remain basic challenges in secondary stroke prevention.Citation4 The literature addressing secondary stroke prevention is vast and impossible to thoroughly discuss in a single paper. This review should be viewed as a summary of the more frequent stroke mechanisms and the available evidence from randomized clinical trials for the best therapies to prevent stroke recurrence.

Ischemic stroke characterization

Knowing the stroke etiology is a critical step in the entire process because both risk-factor modification and stroke prevention begin with appropriate characterization of the stroke mechanism.Citation5 Depending on the stroke mechanism, the risk of recurrence and suggested algorithms to prevent stroke vary.Citation6 The most commonly used classification scheme in ischemic stroke is the Trial of Org10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification, which includes the following five subtypes: large artery atherosclerosis (LAA), cardioembolic, small vessel occlusion (SVO), stroke of undetermined cause (ie, cryptogenic stroke), and stroke of “other” cause.Citation7 Although other classification systems have been suggested,Citation8,Citation9 the TOAST classification remains the most frequently used in large epidemiological studies ().

Table 1 Summary of studies from different ethnic and racial groups that disclosed stroke subtype rates

To determine stroke etiology, a thorough workup is needed to exclude potential stroke mechanisms that may need a change in treatment. In epidemiological studies, the proportion of cryptogenic strokes varies from 13% to 50% according to the workup undertaken.Citation10,Citation11 This underscores the need to carry out an exhaustive workup of patients with strokes.

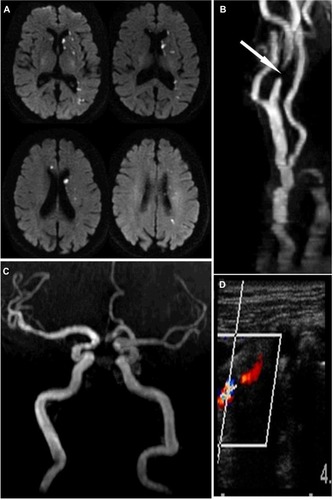

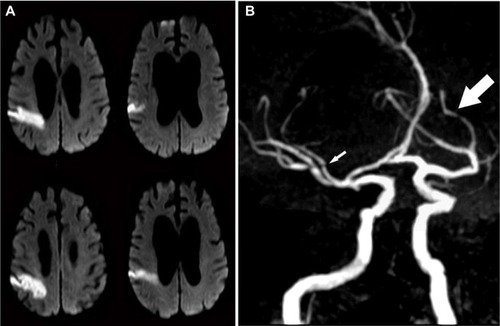

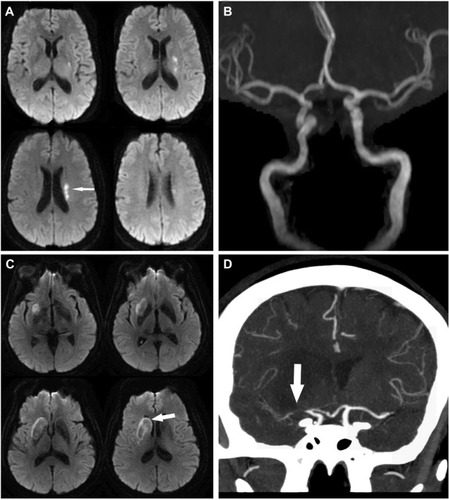

Stroke attributed to LAA is defined as infarction distal to a large vessel stenosis. Frequent sites for atherosclerotic plaques include the aortic arch and ascending aorta, the extracranial carotid artery, and the proximal arteries in the Circle of Willis ( and ).Citation12–Citation14 Ischemia most commonly results from distal embolization of thrombotic products, a so-called artery-to-artery embolism, but it can also be caused by hypoperfusion of brain tissue distal to a severely stenotic or occluded vessel or from branch occlusive disease (–).

Figure 1 Stroke and extracranial carotid atherosclerosis.

Figure 2 Stroke and intracranial atherosclerosis.

Figure 3 Small artery disease versus branch occlusive disease.

To define a stroke as cardioembolic, a clear cardiac source of embolism must be established. The most common etiologies of cardioembolic stroke are atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease, large myocardial infarction (MI), or dilated cardiomyopathy.Citation15–Citation18 On the other hand, strokes that have an associated proximal large vessel stenosis, or that appear most consistent with a lacunar syndrome, can also result from cardioembolism, highlighting the challenges in determining a precise stroke mechanism.Citation19,Citation20 Atrial fibrillation, if paroxysmal, may be elusive. Prolonged cardiac monitoring in patients with stroke deemed “cryptogenic” may reveal occult atrial fibrillation in up to a fifth of patients, compared to only 2% with 7-day cardiac monitoring.Citation21,Citation22 Consequently, a true cryptogenic stroke should typically exclude the presence of occult atrial fibrillation, particularly in subjects >60 years and those with evidence of prior cortical infarcts.Citation23

Stroke from SVO is typically referred to as lacunar stroke, which in modern practice is not limited to a specific size cutoff, but rather defined by anatomical location and a typical lacunar syndrome.Citation19,Citation24 The typical underlying arterial pathology in lacunar infarcts includes microatheroma of the penetrating arteries (most common in the largest infarcts), lypohyalinosis (more frequent in small infarcts), microembolism, or branch occlusive disease (). More recent evidence suggests, however, that SVO and LAA may be the different phenotypic expression of the same underlying intracranial arterial disease, with SVO representing perhaps an earlier form of the disease.Citation25–Citation27 This fact may also explain why the medical therapy for those with SVO and intracranial LAA is similar, despite the higher risk of stroke recurrence noted for those with LAA.Citation13,Citation28 It is also important to recognize that a transient ischemic attack (TIA) calls for the same urgency in evaluation as a stroke. In one study, the risk of stroke after TIA was approximately 5% in the first 2 days and 10% within 90 days.Citation29

General prevention strategies

Antiplatelets

As a group, antiplatelets offer an absolute risk reduction of 2% in vascular events per year, at the cost of a 0.1%–0.3% increase in major extracranial hemorrhages ().Citation30,Citation31 Aspirin is the most extensively studied, cheapest, and most commonly used agent in secondary stroke prevention. The US Food and Drug Administration currently recommends doses between 50 and 325 mg daily for stroke prevention.Citation6 There is no evidence that clopidogrel is superior to aspirin alone for secondary stroke prevention, but clopidogrel seems superior to aspirin in preventing combined vascular outcomes, which is mostly driven by a reduction in leg amputation among patients with peripheral arterial disease.Citation32 Aspirin with extended-release dipyridamole, compared to aspirin alone, produced an approximate annual absolute risk reduction of 1% in two large clinical trials.Citation33,Citation34 Twice-a-day dosing and headache are drawbacks of aspirin with extended-release dipyridamole. On the other hand, a clinical trial investigating the use of clopidogrel vs the combination of aspirin with extended-release dipyridamole failed to show any significant reduction in events that would favor either agent.Citation35 The choice of antiplatelet agents depends on the setting, the patient-specific comorbidities, and the patient’s access to health care. While the low cost of, and extensive experience with, aspirin make it the leading choice in most cases, clopidogrel and aspirin with extended-release dipyridamole are reasonable alternatives as first-line therapy in those who have suffered a stroke.

Table 2 Summary of some of the major studies comparing antiplatelets against each other or against placebo in stroke prevention

Hypertension

Targeting hypertension carries the highest benefit in reducing stroke burden on a population level.Citation3,Citation36 The Perindopril Protection Against Recurrent Stroke Study (PROGRESS) trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of antihypertensive therapy among 6,105 patients with a history of hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke or TIA. Patients were treated with the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor perindopril, with or without the addition of the thiazide diuretic indapamide. Therapy led to a mean blood pressure reduction of 9/4 mmHg and a 4% absolute risk reduction in recurrent stroke, with similar reductions in patients with and without a history of hypertension.Citation37 The Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) trial, aside from studying the effect of dual-antiplatelet therapy, also examined the role of strict vs standard blood pressure management (systolic, <130 mmHg vs 130–149 mmHg) on the outcome of stroke recurrence and showed a trend toward benefit in stroke recurrence in the lower blood pressure group.Citation38 Current American Heart Association guidelines recommend blood pressure goals of, <140 mmHg and diastolic, 90 mmHg; however, there is evidence that the benefit of lowering blood pressure extends to levels far below this cutoff, and as suggested in the PROGRESS trial, treatment should not be reserved for only those with history of hypertension.Citation6,Citation39

Hyperlipidemia

Hypercholesterolemia is another general target in secondary stroke prevention. The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial provided evidence of the benefit of statin therapy among patients with a TIA or stroke within the previous 6 months and no evidence of possible cardioembolic source (eg, atrial fibrillation).Citation40 It enrolled 4,731 patients with a baseline low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level between 100 and 190 mg/dL. Over a period of nearly 5 years, atorvastatin reduced the 5-year risk of recurrent stroke, from 13.1% to 11.2%. Although participants who took atorvastatin had a higher incidence of hemorrhagic stroke, there were no differences in mortality compared to placebo. There was also no difference seen in the efficacy of atorvastatin based on stroke mechanism.Citation41 As a result, statins have become the mainstay in lipid reduction therapy after a stroke or TIA.

Diabetes

Diabetes is one of the most important vascular risk factors for stroke and a high-yield target for preventive measures. Among patients with diabetes, the risk of vascular events is increased thrice compared to nondiabetics, and in combinations with other risk factors, the risk increases exponentially compared to individuals with those risk factors without diabetes.Citation42 Intensive glycemic control (defined as glycated hemoglobin, <7%) was not associated with a significant reduction in the rates of stroke (fatal or nonfatal) among patients with diabetes, although there was a reduction of 16% in a combined vascular outcome.Citation33 A recent meta-analysis of clinical trials comparing intensive glycemic control vs standard glycemic controls demonstrated a non-statistically significant 7% risk reduction among those in the intensive care group.Citation34 An early, aggressive control of glycemia has lasting benefits in vascular events in patients with type I diabetes, and the long-term favorable results of intensive glucose lowering among those with type II diabetes argues for an early recognition of diabetes as the most effective way to reduce the risk of vascular events and stroke.Citation43,Citation44 Patients with diabetes frequently have other vascular risk factors that should be aggressively controlled. For example, selected patients with diabetes (ie, young patients) should have a blood pressure target of, <130/80 mmHg if tolerated.Citation45

Lifestyle modification

Apart from pharmacological therapy, lifestyle modification, including a healthy diet, regular physical activity, and weight loss in overweight or obese patients, may have substantial benefits on blood pressure and lipid levels and, ultimately, stroke recurrence. Diet is probably the best studied when it comes to stroke prevention and the Mediterranean diet has been shown to protect against cardiovascular disease and specifically stroke, decreasing 5-year stroke risk by approximately 30%.Citation46 In general, a diet that encourages a high intake of plant-based nutrients, low salt intake, and a limited intake of saturated fats and simple sugars is likely to have significant cardiovascular benefits if adhered to for a long period of time. Tobacco use should be strongly discouraged and among smokers, smoking cessation leads to a significant reduction in stroke risk.Citation47 Furthermore, obesity is an independent risk factor for stroke, even after adjusting for physical activity and diet.Citation4 Behavioral risk factors may be the most difficult to control, making patient education and a multidisciplinary approach extremely important.

Secondary stroke prevention by specific mechanisms

Cardioembolism

Atrial fibrillation

The biggest modifier of stroke risk in persons with atrial fibrillation is anticoagulation (). When atrial fibrillation from a non-valvular cause is discovered, long-term stroke risk can be quantified using the CHADS2 or CHADS2-VASc prediction scoring systems, with CHA2DS2-VASc being preferred in recent American and European guidelines.Citation48–Citation50 Included in both scores are age >75 years, history of congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and previous stroke. The sole presence of one risk factor (other than history of stroke) places the patient at a low risk of systemic cardioembolism, while an annual stroke risk of >1% based on the CHA2DS2-VASc score is typically considered the threshold to discuss the initiation of anticoagulation. This must be weighed against the risk of bleeding associated with anticoagulation.

Table 3 Stroke mechanism and the estimated risk of stroke recurrence in the setting of prevention therapy

When used for stroke prevention from atrial fibrillation, warfarin is associated with a 60%–70% relative risk reduction in stroke and has been the gold standard in primary and secondary stroke prevention in patients with known persistent or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation.Citation15 More recently, a set of novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have been approved specifically for thromboembolism prophylaxis in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. When directly compared to warfarin in large randomized clinical trials, NOACs showed similar efficacy in preventing ischemic stroke and a relatively lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) compared to warfarin.Citation51–Citation54

Currently, there are four NOACs approved for prevention of stroke. They fall into the categories of either direct thrombin inhibitors or factor Xa inhibitors. They are dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban. Although their relative ease of use and lack of need for routine blood checks have made them popular first-line choices among some, the challenge and current-day dilemmas lie in the lack of monitoring assays, the lack of antidote, and the pricing, particularly for developing countries. There are, however, candidates on the horizon for an assay that can quickly and reliably track level of anticoagulation.Citation55 This may be especially important in those with renal impairment, which has been shown to increase the risk of hemorrhagic complications with some of these agents.Citation55

The lack of an antidote to reverse the therapeutic effects of the NOACs may be offset by lesser risk of ICH compared to warfarin.Citation56 Further, individualized risk of in-hospital mortality from ICH was studied in a retrospective analysis, and no difference in outcome was seen in patients experiencing ICH secondary to warfarin compared to in patients who had been on dabigatran.Citation57 This suggests that the lack of an antidote should not dissuade physicians from using dabigatran (and presumably any of the other NOACs) over warfarin. Currently, PER977 – small synthetic cationic molecule – is being investigated as a possible antidote to all of the NOACs alike.Citation58

The greatest challenge in the prophylactic use of anticoagulation in the setting of atrial fibrillation revolves around the risk of ICH vs the benefit of preventing ischemic stroke.Citation59 The HAS-BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile international normalized ratio, Elderly [>65 years], Drugs/alcohol concomitantly) and ATRIA (Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation) prediction scoring systems are clinical decision-making tools that can aid the clinician in quantifying risk of hemorrhage, which can then be compared to yearly risk of stroke using CHADS2-VASc, to guide the clinician in how to best proceed.Citation60,Citation61

Until recently, patients with a high risk of bleeding had to be placed on less protective agents like aspirin, clopidogrel, or a combination of the two, as opposed to standard therapy with anticoagulation. In March 2015, the WATCHMAN™ Left Atrial Appendage Closure Device was approved for use in the USA for the treatment of atrial fibrillation based on two trials showing non-inferiority to warfarin.Citation62,Citation63 Currently, the procedure is being offered to patients who carry a significant hemorrhagic risk with anticoagulation or have other contraindications to anticoagulation therapy. The caveat with using WATCHMAN is that patients need to be able to tolerate warfarin plus aspirin for at least 45 days (discontinued after there is proof of closure of the left atrial appendage) and dual antiplatelets for at least 6 months, which presents a challenge to the applicability of the WATCHMAN device to the FDA-approved high-risk population.Citation63

Prosthetic cardiac valves

The risk of major embolism among patients with mechanical valves is estimated to be 4% per year without antithrombotic or anticoagulation therapy, 2% with the use of aspirin, and 1% with the use of anticoagulation.Citation64 Anticoagulation with warfarin and occasionally with the additional low-dose aspirin (depending on comorbidities) is therefore indicated in patients with mechanical valves.Citation65 Among patients with mechanical valves, NOACs are contraindicated.Citation66 In patients with bioprosthetic valves, the risk of embolism is less compared to in those with mechanical valves, and a single antiplatelet is usually recommended for secondary stroke prophylaxis, although a short course of anticoagulation after implantation may be reasonable.Citation65,Citation67

Low ejection fraction

After an anterior wall MI, a third of patients develop a thrombus and a third of these have embolization.Citation68 Predictors of left ventricular thrombus are low ejection fraction (EF), worsening EF after discharge, and wall dyskinesis.Citation69 The most consistent predictor of embolization is thrombus mobility.Citation68,Citation69 It is considered reasonable to use short-term anticoagulation in patients with MI and evidence of left ventricular thrombus and in those with wall dyskinesis, but randomized data to universally recommend this intervention are lacking.Citation70

Anticoagulation with warfarin in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy with an EF <35% and a sinus rhythm was studied in one large trial warfarin and aspirin in patients with heart failure and sinus rhythm (WARCEF) and while the warfarin group had a lower incidence of ischemic stroke, any benefit was offset by an overall increase in major hemorrhage.Citation16 Among WARCEF participants <60 years old, however, there was a benefit with anticoagulation vs aspirin, even after taking into account the rates of bleeding.Citation71 In further subgroup analysis, those with prior stroke and an EF <15% had a stroke risk of 6% per year, suggesting that in this high-risk group, the preventive effects of warfarin may offset the risk of hemorrhage.Citation72 As a result, warfarin is currently not indicated for the sole purpose of stroke prevention in dilated cardiomyopathy with low EF and its use in some of the mentioned subgroups should be carefully discussed with the patients and their families.

Aortic atheroma

Complex aortic arch plaques, defined by a protruding component >4 mm, presence of a mobile component, or intraplaque ulceration, are deemed high risk for embolization.Citation73 The 2-year risk of stroke or death among individuals with aortic plaques <4 mm was 16.5% compared to 26.7% in those with plaques ≥4 mm.Citation74 In this observational study, the rate of events was similar among those using antiplatelets or warfarin. Whether anticoagulation reduces incident vascular events compared to antiplatelets in patients with aortic plaques >4 mm has been formally explored in a clinical trial.Citation75 The primary endpoint (cerebral infarction, MI, peripheral embolism, vascular death, or ICH) in the group on anticoagulation occurred in 11.0% vs 7.6% in the dual-antiplatelet group, failing to reach statistical significance (probably due to the low rate of events). Further, the group on anticoagulation had a higher incidence of vascular death and ICH. There is therefore no clear evidence to support the systematic use of anticoagulation in patients with aortic arch atheroma.

Patent foramen ovale

The role of anticoagulation among patients with possible paradoxical embolism through a patent foramen ovale (PFO) is unclear, and current guidelines support the use of antiplatelet agents for secondary prevention in this setting.Citation76 Three large clinical trials have investigated whether closure of PFOs using trans-cardiac devices can reduce secondary stroke risk compared to medical therapy. None of them was able to show benefit of PFO closure when compared to medical therapy alone, in the intention-to-treat analysis.Citation77–Citation79 Importantly, the yearly rates of stroke differed among these trials. In the closure or medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke with patent foramen ovale (CLOSURE) I trial, the 2-year rate of stroke recurrence was 7% in the medical group, while in the closure of patent foramen ovale versus medical therapy after cryptogenic stroke (RESPECT) and percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic embolism (PC) trials (with more stringent criteria for ruling out alternative stroke mechanisms), the rates were closer to 1% per year. This discrepancy is in itself a challenge to the interpretation of these trials, but suggests that in studies reporting a high rate of stroke recurrence attributed to a PFO, participants have alternative stoke mechanisms that are not modified by closing a PFO. Ideally, clinical trials assessing whether closing the PFO reduces the risk of stroke recurrence would benefit from using a probabilistic model like the RoPE (Risk of Paradoxical Embolism) score to identify those with the highest likelihood for a causal role of the PFO, after exhaustive workup to rule out alternative etiologies.Citation80 Until stronger data exist to justify the use of a device to close the PFO and its potential risks, a single daily antiplatelet seems a reasonable recommendation in patients with truly cryptogenic strokes.

Extracranial carotid atherosclerosis

Extracranial carotid artery stenosis is most effectively treated with endarterectomy or stenting (). There have been a number of studies comparing best medical management vs carotid endarterectomy (CEA) in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis. The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial demonstrated a risk reduction of 17% in all ipsilateral stroke recurrence, and 11% in ipsilateral major or fatal strokes.Citation81 Post hoc analysis of this study demonstrated that the greatest value of CEA comes if the procedure is done within 2 weeks of the stroke.Citation82 The European Carotid Surgery Trial showed a comparable risk reduction in the surgical arm for patients with carotid stenosis >80%. An analysis of pooled data for symptomatic carotid stenosis trials demonstrated robust beneficial effects of surgical interventions across trials in stenosis of ≥70%, with more marginal effects with lesser degrees of stenosis or in those with carotid occlusion.Citation83 Among patients with carotid occlusion and evidence of increased oxygen extraction in the ipsilateral hemisphere (ie, at the greatest risk of recurrent stroke), an extracranial–intracranial arterial bypass failed to reduce the risk of stroke recurrence in one study.Citation84

Three large trials have assessed whether carotid artery stenting (CAS) is as equally effective as CEA among patients with symptomatic extracranial carotid atherosclerosis.Citation14,Citation85,Citation86 The results consistently show a slight increase in periprocedural stroke (30 days) with CAS compared to CEA. Combined adverse outcomes over a 2-year period are similar, however, establishing CAS as a viable option for treating severe symptomatic carotid stenosis in high-risk surgical patients or those with unsuitable anatomy.

In patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis, older evidence suggested a benefit in CEA vs medical therapy, but the effect size was more modest and the benefit delayed, compared to the benefit observed for patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis.Citation87,Citation88 Furthermore, the advent of statins and more aggressive medical therapy may have reduced the differential effects of surgical intervention compared to modern medical therapy. Based on this presumed medical equipoise, a new trial will investigate the effect modification of CEA or carotid stenting against medical therapy in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis.Citation89

Intracranial LAA

Several trials have investigated the best possible treatment in stroke recurrence in the setting of intracranial vessel stenosis (). The Warfarin and Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) trial studied aspirin vs warfarin in patients with verified 50%–99% stenosis of a major intracranial artery (carotid, middle cerebral, vertebral, or basilar arteries).Citation13 Even though the study was stopped early because of the high rate of adverse events in the warfarin group, it showed a 20% 2-year risk of overall stroke recurrence and a 15% 2-year risk of stroke recurrence in the vascular territory distal to the stenosis.Citation13

To directly address this high-risk group of patients, the Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) trial attempted to follow the therapeutic model used in coronary artery disease by comparing percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting to best medical therapy in patients with recent stroke and proximal intracranial arterial stenosis of >70%.Citation90 Both groups received aggressive lifestyle modification counseling and intervention and were placed on dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for 3 months. The final outcome of stroke or death occurred in 20% in the stenting group and 12% in the medical group at 1 year. The majority of strokes in the intervention arm were perioperative, occurring in the first 30 days. Although a recurrence of 12% per year among those with medical therapy is intolerably high, aggressive medical therapy appears to be the only proven therapy recommended for patients with intracranial LAA. Novel therapies are evidently and urgently needed to further reduce the risk of stroke recurrence among this population.

Small artery occlusion/lacunar stroke

Antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin, compared to aspirin alone, was investigated as secondary prevention after lacunar stroke in the SPS3 trial.Citation28 There was no evidence of a reduction in the rates of recurrent strokes using dual antiplatelets vs aspirin alone (2.5% vs 2.7% per year), but an increase in the risk of bleeding and mortality was noted in the dual-antiplatelet therapy group. Based on this, there is no evidence to support the use of dual antiplatelets to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke in the long-term.

In the short-term, however, there may be a role for the use of dual antiplatelets in “minor” strokes or TIA. The Clopidogrel in High-risk Patients with Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events (CHANCE) trial found that a 21-day course of dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel among Chinese patients with TIA and minor stroke, given within 24 hours of symptom onset, lowered the 3-month stroke recurrence rate.Citation91 The majority of the benefit from dual-antiplatelet therapy in CHANCE occurred within the first week of treatment. A short course of aspirin and clopidogrel in the early period may therefore be considered, but whether these results are applicable to non-Chinese populations will be further investigated in the Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA (POINT) trial.Citation92

Future directions/Conclusion

Preventing stroke recurrence is one of the major concerns of practitioners who treat patients with stroke, either in the hospital or in the clinic. Determining the potential causal mechanisms of a patient’s stroke offers the opportunity to establish tailored therapies, while in the hospital or shortly after, for extracranial carotid stenosis, intracranial large artery stenosis with fow failure, cardiac thrombus in the setting of low EF and/or atrial fibrillation. Defining stroke mechanism, however, is challenging and, as discussed, it is crucial that physicians exhaustively rule out alternative etiologies for stroke. In the case of mixed etiologies (eg, intracranial atherosclerosis in patient with atrial fibrillation), the proven treatment for the conditions with the highest risk of recurrence might be indicated. A comprehensive stroke workup is expensive, and it may not be within reach in developing countries where stroke represents an even greater challenge. Developing cheaper methods to more accurately ascertain stroke mechanism may be a way to overcome this challenge.

Furthermore, although clinical trials have framed and keep fine-tuning the major therapeutic axis for stroke prevention, there are still many uncertainties in specific conditions with higher risk of stroke. These less frequent, and consequently less well-studied, conditions or clinical scenarios lead to heterogeneous patterns of practice that may result in more expensive treatment or even worse – harm to patients. Collaborations across major academic centers and integrated electronic systems may offer an opportunity to study outcomes in some of these cases, which may lead to a more unified and better informed approach to treat patients with stroke.

Finally, in our view, the greatest challenge is that, even with the best medical therapies, the recurrence rates of stroke are not zero, and one out of four patients who have had strokes in the USA has a recurrent event. It is imperative to foster the development of newer therapies to reduce even further the risk of stroke recurrence. Given the unacceptably high risk of stroke recurrence with traditional vascular disease, a stronger effort is needed in controlling vascular risk factor on a population-based level.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SaccoRLKasnerSEBroderickJPAmerican Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and AnesthesiaCouncil on Cardiovascular Radiology and InterventionCouncil on Cardiovascular and Stroke NursingAn updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke AssociationStroke20134472064208923652265

- MozaffarianDBenjaminEJGoASAmerican Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics SubcommitteeHeart disease and stroke statistics – 2015 update: a report from the American Heart AssociationCirculation20151314e29e32225520374

- O’DonnellMJXavierDLiuLINTERSTROKE investigatorsRisk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control studyLancet2010376973511212320561675

- LacklandDTRoccellaEJDeutschAFAmerican Heart Association Stroke CouncilCouncil on Cardiovascular and Stroke NursingCouncil on Quality of Care and Outcomes ResearchCouncil on Functional Genomics and Translational BiologyFactors influencing the decline in stroke mortality: a statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke AssociationStroke201445131535324309587

- BamfordJSandercockPDennisMBurnJWarlowCClassification and natural history of clinically identifiable subtypes of cerebral infarctionLancet19913378756152115261675378

- KernanWNOvbiageleBBlackHRAmerican Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular DiseaseGuidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke AssociationStroke20144572160223624788967

- AdamsHPJrBendixenBHKappelleLJClassification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke TreatmentStroke199324135417678184

- AyHFurieKLSinghalASmithWSSorensenAGKoroshetzWJAn evidence-based causative classification system for acute ischemic strokeAnn Neurol200558568869716240340

- AyHBennerTArsavaEMA computerized algorithm for etiologic classification of ischemic stroke: the Causative Classification of Stroke SystemStroke200738112979298417901381

- GutierrezJKochSDongCRacial and ethnic disparities in stroke subtypes: a multiethnic sample of patients with strokeNeurol Sci2014354877582

- SchneiderATKisselaBWooDIschemic stroke subtypes: a population-based study of incidence rates among blacks and whitesStroke20043571552155615155974

- Atherosclerotic disease of the aortic arch as a risk factor for recurrent ischemic stroke. The French Study of Aortic Plaques in Stroke GroupN Engl J Med199633419121612218606716

- ChimowitzMILynnMJHowlett-SmithHWarfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Trial InvestigatorsComparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosisN Engl J Med2005352131305131615800226

- BrottTGHobsonRW2ndHowardGCREST InvestigatorsStenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid-artery stenosisN Engl J Med20103631112320505173

- Warfarin versus aspirin for prevention of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation: Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation II StudyLancet199434388996876917907677

- HommaSThompsonJLPullicinoPMWARCEF InvestigatorsWarfarin and aspirin in patients with heart failure and sinus rhythmN Engl J Med2012366201859186922551105

- JugduttBISivaramCAProspective two-dimensional echocardiographic evaluation of left ventricular thrombus and embolism after acute myocardial infarctionJ Am Coll Cardiol19891335545642918160

- PettyGWKhandheriaBKWhisnantJPSicksJDO’FallonWMWiebersDOPredictors of cerebrovascular events and death among patients with valvular heart disease: a population-based studyStroke200031112628263511062286

- GanRSaccoRLKargmanDERobertsJKBoden-AlbalaBGuQTesting the validity of the lacunar hypothesis: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study experienceNeurology1997485120412119153444

- FisherCMLacunar strokes and infarcts: a reviewNeurology19823288718767048128

- RitterMAKochhäuserSDuningTOccult atrial fibrillation in cryptogenic stroke: detection by 7-day electrocardiogram versus implantable cardiac monitorsStroke20134451449145223449264

- SannaTDienerHCPassmanRSCRYSTAL AF InvestigatorsCryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med2014370262478248624963567

- FavillaCGIngalaEJaraJPredictors of finding occult atrial fibrillation after cryptogenic strokeStroke20154651210121525851771

- ArboixAMartí-VilaltaJLLacunar strokeExpert Rev Neurother20099217919619210194

- KasnerSEChimowitzMILynnMJWarfarin Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Trial InvestigatorsPredictors of ischemic stroke in the territory of a symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosisCirculation2006113455556316432056

- LavalléePCLabreucheJFailleDLacunar-BICHAT InvestigatorsCirculating markers of endothelial dysfunction and platelet activation in patients with severe symptomatic cerebral small vessel diseaseCerebrovasc Dis201336213113824029712

- DeplanqueDLavalleePCLabreucheJLacunar-BICHAT InvestigatorsCerebral and extracerebral vasoreactivity in symptomatic lacunar stroke patients: a case-control studyInt J Stroke20138641342122336034

- SPS3 InvestigatorsBenaventeORHartRGEffects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar strokeN Engl J Med2012367981782522931315

- JohnstonSCSidneySBernsteinALGressDRA comparison of risk factors for recurrent TIA and stroke in patients diagnosed with TIANeurology200360228028512552045

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) CollaborationBaigentCBlackwellLAspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trialsLancet200937396781849186019482214

- ATT CollaborationCollaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patientsBMJ20023247329718611786451

- CAPRIE Steering CommitteeA randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering CommitteeLancet19963489038132913398918275

- Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) GroupLancet199835291318378539742976

- RayKKSeshasaiSRWijesuriyaSEffect of intensive control of glucose on cardiovascular outcomes and death in patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsLancet200937396771765177219465231

- SaccoRLDienerHCYusufSPRoFESS Study GroupAspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent strokeN Engl J Med2008359121238125118753638

- WilleyJZMoonYPKahnEPopulation attributable risks of hypertension and diabetes for cardiovascular disease and stroke in the northern Manhattan studyJ Am Heart Assoc201435e00110625227406

- PROGRESS Collaborative GroupRandomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attackLancet200135892871033104111589932

- SPS3 Study GroupBenaventeORCoffeyCSBlood-pressure targets in patients with recent lacunar stroke: the SPS3 randomised trialLancet2013382989150751523726159

- LawMRMorrisJKWaldNJUse of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studiesBMJ2009338b166519454737

- AmarencoPBogousslavskyJCallahanA3rdStroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) InvestigatorsHigh-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attackN Engl J Med2006355654955916899775

- AmarencoPBenaventeOGoldsteinLBStroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels InvestigatorsResults of the Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial by stroke subtypesStroke20094041405140919228842

- StamlerJVaccaroONeatonJDWentworthDDiabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention TrialDiabetes Care19931624344448432214

- HolmanRRPaulSKBethelMAMatthewsDRNeilHA10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetesN Engl J Med2008359151577158918784090

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) Research GroupNathanDMZinmanBModern-day clinical course of type 1 diabetes mellitus after 30 years’ duration: the diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications and Pittsburgh epidemiology of diabetes complications experience (1983–2005)Arch Intern Med2009169141307131619636033

- Arauz-PachecoCParrottMARaskinPAmerican Diabetes AssociationTreatment of hypertension in adults with diabetesDiabetes Care200326Suppl 1S80S8212502624

- EstruchRRosEMartínez-GonzálezMAMediterranean diet for primary prevention of cardiovascular diseaseN Engl J Med2013369767667723944307

- WolfPAD’AgostinoRBKannelWBBonitaRBelangerAJCigarette smoking as a risk factor for stroke. The Framingham StudyJAMA19882597102510293339799

- GageBFWatermanADShannonWBoechlerMRichMWRadfordMJValidation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial FibrillationJAMA2001285222864287011401607

- LipGYNieuwlaatRPistersRLaneDACrijnsHJRefining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillationChest2010137226327219762550

- CammAJLipGYDe CaterinaRESC Committee for Practice Guidelines-CPGDocument Reviewers2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation – developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm AssociationEuropace201214101385141322923145

- ConnollySJEzekowitzMDYusufSRE-LY Steering Committee and InvestigatorsDabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med2009361121139115119717844

- GrangerCBAlexanderJHMcMurrayJJARISTOTLE Committees and InvestigatorsApixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med20113651198199221870978

- PatelMRMahaffeyKWGargJROCKET AF Investigators. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med20113651088389121830957

- GiuglianoRPRuffCTBraunwaldEENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 InvestigatorsEdoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med2013369222093210424251359

- AvecillaSTFerrellCChandlerWLReyesMPlasma-diluted thrombin time to measure dabigatran concentrations during dabigatran etexilate therapyAm J Clin Pathol2012137457257422431533

- MillerCSGrandiSMShimonyAFilionKBEisenbergMJMetaanalysis of efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillationAm J Cardiol2012110345346022537354

- AlonsoABengtsonLGMacLehoseRFLutseyPLChenLYLakshminarayanKIntracranial hemorrhage mortality in atrial fibrillation patients treated with dabigatran or warfarinStroke20144582286229124994722

- AnsellJEBakhruSHLaulichtBEUse of PER977 to reverse the anticoagulant effect of edoxabanN Engl J Med2014371222141214225371966

- MorgensternLBHemphillJC3rdAndersonCGuidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke AssociationStroke20104192108212920651276

- PistersRLaneDANieuwlaatRde VosCBCrijnsHJLipGYA novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart SurveyChest201013851093110020299623

- SingerDEChangYBorowskyLHA new risk scheme to predict ischemic stroke and other thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation: the ATRIA study stroke risk scoreJ Am Heart Assoc201323e00025023782923

- ReddyVYHolmesDDoshiSKNeuzilPKarSSafety of percutaneous left atrial appendage closure: results from the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage System for Embolic Protection in Patients with AF (PROTECT AF) clinical trial and the Continued Access RegistryCirculation2011123441742421242484

- HolmesDRJrKarSPriceMJProspective randomized evaluation of the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: the PREVAIL trialJ Am Coll Cardiol201464111224998121

- CannegieterSCRosendaalFRBriëtEThromboembolic and bleeding complications in patients with mechanical heart valve prosthesesCirculation19948926356418313552

- NishimuraRAOttoCMBonowRO2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice GuidelinesJ Thorac Cardiovasc Surg20141481e1e13224939033

- EikelboomJWConnollySJBrueckmannMRE-ALIGN InvestigatorsDabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valvesN Engl J Med2013369131206121423991661

- BrennanJMEdwardsFHZhaoYDEcIDE AVR (Developing Evidence to Inform Decisions about Effectiveness–Aortic Valve Replacement) Research TeamLong-term safety and effectiveness of mechanical versus biologic aortic valve prostheses in older patients: results from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery National DatabaseCirculation2013127161647165523538379

- JohannessenKANordrehaugJEvon der LippeGVollsetSERisk factors for embolisation in patients with left ventricular thrombi and acute myocardial infarctionBr Heart J19886021041103415869

- KerenAGoldbergSGottliebSNatural history of left ventricular thrombi: their appearance and resolution in the posthospitalization period of acute myocardial infarctionJ Am Coll Cardiol19901547908002307788

- O’GaraPTKushnerFGAscheimDDAmerican College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice GuidelinesCirculation20131274e362e42523247304

- HommaSThompsonJLSanfordARWARCEF InvestigatorsBenefit of warfarin compared with aspirin in patients with heart failure in sinus rhythm: a subgroup analysis of WARCEF, a randomized controlled trialCirc Heart Fail20136598899723881846

- PullicinoPMQianMSaccoRLRecurrent stroke in the warfarin versus aspirin in reduced cardiac ejection fraction (WARCEF) trialCerebrovasc Dis201438317618125300706

- MeierBFrankBWahlADienerHCSecondary stroke prevention: patent foramen ovale, aortic plaque, and carotid stenosisEur Heart J2012336705713713a713b22422912

- Di TullioMRRussoCJinZSaccoRLMohrJPHommaSPatent Foramen Ovale in Cryptogenic Stroke Study InvestigatorsAortic arch plaques and risk of recurrent stroke and deathCirculation2009119172376238219380621

- AmarencoPDavisSJonesEFClopidogrel plus aspirin versus warfarin in patients with stroke and aortic arch plaquesStroke20144551248125724699050

- FurieKLKasnerSEAdamsRJAmerican Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes ResearchGuidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke associationStroke201142122727620966421

- CarrollJDSaverJLThalerDERESPECT InvestigatorsClosure of patent foramen ovale versus medical therapy after cryptogenic strokeN Engl J Med2013368121092110023514286

- MeierBKalesanBMattleHPPC Trial InvestigatorsPercutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic embolismN Engl J Med2013368121083109123514285

- FurlanAJReismanMMassaroJCLOSURE I Investigators. Closure or medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke with patent foramen ovaleN Engl J Med20123661199199922417252

- KentDMRuthazerRWeimarCAn index to identify stroke-related vs incidental patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic strokeNeurology201381761962523864310

- North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial CollaboratorsBeneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosisN Engl J Med199132574454531852179

- FergusonGGEliasziwMBarrHWThe North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial: surgical results in 1415 patientsStroke19993091751175810471419

- RothwellPMEliasziwMGutnikovSACarotid Endarterectomy Trialists’ CollaborationAnalysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosisLancet2003361935210711612531577

- PowersWJClarkeWRGrubbRLJrVideenTOAdamsHPJrDerdeynCPCOSS InvestigatorsExtracranial-intracranial bypass surgery for stroke prevention in hemodynamic cerebral ischemia: the Carotid Occlusion Surgery Study randomized trialJAMA2011306181983199222068990

- EcksteinHHRinglebPAllenbergJRResults of the Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy (SPACE) study to treat symptomatic stenoses at 2 years: a multinational, prospective, randomised trialLancet Neurol200871089390218774746

- International Carotid Stenting Study InvestigatorsEderleJDobsonJCarotid artery stenting compared with endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis (International Carotid Stenting Study): an interim analysis of a randomised controlled trialLancet2010375971998599720189239

- Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis StudyJAMA199527318142114287723155

- HallidayAMansfieldAMarroJMRC Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST) Collaborative Group. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trialLancet200436394201491150215135594

- BrottTGCarotid Revascularization and Medical Management for Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis Trial (CREST-2)ClinicalTrials.gov [website on the Internet]Bethseda, MDUS National Library of Medicine2014 [updated May 27, 2015]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02089217. NLM identifier: NCT02089217Accessed April 14, 2015

- DerdeynCPChimowitzMILynnMJStenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis Trial InvestigatorsAggressive medical treatment with or without stenting in high-risk patients with intracranial artery stenosis (SAMMPRIS): the final results of a randomised trialLancet2014383991433334124168957

- WangYWangYZhaoXCHANCE InvestigatorsClopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attackN Engl J Med20133691111923803136

- JohnstonSCEastonJDFarrantMPlatelet-oriented inhibition in new TIA and minor ischemic stroke (POINT) trial: rationale and designInt J Stroke20138647948323879752

- Sevush-GarcyJGutierrezJAn epidemiological perspective on race/ethnicity and strokeCurr Cardiovasc Risk Rep2015919

- No authors listedThe European Stroke Prevention Study (ESPS). Principal end-points. The ESPS GroupLancet198728572135113542890951

- No authors listedCAST: randomised placebo-controlled trial of early aspirin use in 20,000 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. CAST (Chinese Acute Stroke Trial) Collaborative GroupLancet19973499066164116499186381

- No authors listedThe International Stroke Trial (IST): a randomised trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19435 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. International Stroke Trial Collaborative GroupLancet19973499065156915819174558

- BousserMGEschwegeEHaguenauM“AICLA” controlled trial of aspirin and dipyridamole in the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic cerebral ischemiaStroke19831415146401878

- DienerHCBogousslavskyJBrassLMAspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet2004364943133133715276392

- DienerHCCunhaLForbesCSiveniusJSmetsPLowenthalAEuropean Stroke Prevention Study. 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of strokeJ Neurol Sci19961431-21138981292

- FarrellBGodwinJRichardsSWarlowCThe United Kingdom transient ischaemic attack (UK-TIA) aspirin trial: final resultsJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry19915412104410541783914

- ESPRIT Study GroupHalkesPHvan GijnJKappelleLJKoudstaalPJAlgraAAspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin alone after cerebral ischaemia of arterial origin (ESPRIT): randomised controlled trialLancet200636795231665167316714187

- EAFT (European Atrial Fibrillation Trial) Study GroupSecondary prevention in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation after transient ischaemic attack or minor strokeLancet19933428882125512627901582