Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, with a projected number of 1 million affected subjects in Germany. Changes in age structure of the Western population allow for the assumption that the number of concerned people is going to be doubled, maybe tripled, by the year 2050. Large epidemiological investigations showed that AF leads to a significant increase in mortality and morbidity. Approximately one-third of all strokes are caused by AF and, due to thromboembolic cause, these strokes are often more severe than those caused by other etiologies. Silent brain infarction is defined as the presence of cerebral infarction in the absence of corresponding clinical symptomatology. Progress in imaging technology simplifies diagnostic procedures of these lesions and leads to a large amount of diagnosed lesions, but there is still no final conclusion about frequency, risk factors, and clinical relevance of these infarctions. The prevalence of silent strokes in patients with AF is higher compared to patients without AF, and several studies reported high incidence rates of silent strokes after AF ablation procedures. While treatment strategies to prevent clinically apparent strokes in patients with AF are well investigated, the role of anticoagulatory treatment for prevention of silent infarctions is unclear. This paper summarizes developments in diagnosis of silent brain infarction and its context to AF.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, affecting an estimated 1% of the population.Citation1 Its prevalence increases age dependently, from <0.1% in adults younger than 55 years to 8% in persons aged 80 years or older.Citation1 Approximately every fourth person over 40 years will suffer from AF in his or her life.Citation2 Changes in the age structure of Western populations lead to the assumption that the number of affected patients will at least duplicate by the year 2050.Citation1 Large trials and epidemiological investigations showed a doubled increase in mortality in AF patients,Citation3,Citation4 including patients with “silent AF”.Citation5 Approximately one-third of all strokes are caused by AF, and AF-caused strokes are often more severe than non-AF-related strokes.Citation6–Citation9 Data from the Framingham Study showed a three- to five fold increased risk of stroke in AF patients.Citation10,Citation11 AF often occurs with no or only few symptoms and is therefore often undiagnosed or only diagnosed when complications like stroke or heart failure occur.Citation5,Citation12 On the other hand, many studies reported a significantly higher percentage of silent strokes in AF patients diagnosed by different methods of cerebral imaging compared to patients without AF history.Citation13–Citation16 Effective oral anticoagulation (OAC) therapy can decrease the rate of stroke up to 80% in AF.Citation17

Silent cerebral infarction (SCI) is defined as the presence of cerebral infarction in the absence of corresponding clinical symptomatology. SCI is a part of cerebral small-vessel disease, which includes white matter hyperintensities and cerebral microbleeds.Citation18 Progress in imaging technology simplifies diagnostic procedures of these lesions. There is still no final conclusion about frequency, risk factors, and clinical relevance of these lesions.

AF patients with silent and hitherto undiagnosed stroke are often not treated with oral anticoagulants, and the impact of this therapy on SCIs remains unclear and needs further investigation.Citation19

Silent stroke and silent cerebral lesions

Prevalence and incidence of silent strokes in common populations

In 1965 FisherCitation20 first described cerebral infarction without any clinic symptoms. Studies of the past years showed that these lesions are not as benign as originally thought.Citation21 In long-term analyses, these lesions correlate with neurological and cognitive deficits and psychiatric disorders in elderly patients.Citation21 Silent cerebral ischemia is now recognized as part of a spectrum of cerebrovascular disease, which also includes transient ischemic attack (TIA) and stroke.Citation18 A change in terminology to “covert infarction” is in discussion.Citation22

Depending on the definition of stroke, prevalence of SCI can range. A prevalence of 10.7% was mentioned in the Framingham Offspring study.Citation23 In this study, stroke was defined by clinical symptoms for more than 24 hours. Most remaining published community sample studies showed a prevalence between 10% and 20%. In Routine Health Care Studies, an SCI range between 5% and 62% has been reported.Citation21 Incidence data are rare. Rates from 1.9% to 3.7% per year are reported, with patients age being an important risk factor for SCI.Citation21 Uehara et alCitation24 showed that 8% of the 60–69-year old participants had new lesions over the duration of follow-up and that 22% of those patients were older than 80 years. The Rotterdam Scan Study examined 1,077 patients without clinical symptoms or history of stroke. Statistical analyses showed an increased risk of 8% per year for an SBI after reaching the age of 60 years.Citation25 In conclusion, SCIs are approximately ten times more frequent than a stroke.Citation26

Diagnosis of SCI

Most studies use diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI). Data show a significantly higher sensitivity to detect lesions than computed tomography (CT).Citation27,Citation28 Information from earlier studies using autopsy is unclear because of the limited sensitivity to detect small lesions due to thick slices and large interslice gaps.Citation29

Cerebral ischemia can be detected within minutes after onset by detection of a hyperintense lesion on DWI indicating cellular edema and hypointense presentation in apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map. In contrast to ADC map detection, the T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inverse recovery sequence (FLAIR) turns positive in delay.Citation30 To distinguish silent brain infarction from dilated Virchow–Robin spaces and leukaraiosis, additional criteria include a lesion size of 3 mm or greater and presence of a hyperintense rim around the hypointense lesion on FLAIR images.Citation29,Citation31

Further improvement in imaging modalities gives the possibility of further subclassification of silent brain infarction. A silent cerebral event (SCE) is defined as an acute new hyperintense DWI-lesion with reduced ADC.Citation30 Recent publications renounce FLAIR positivity because of delayed detection and reduced sensitivity for early diagnosis of SCI.Citation32 FLAIR-positive MRI lesions were differentiated as silent cerebral lesions (SCLs; and ). The best time point for brain MRI evaluation of SCI in asymptomatic patients is still unclear.Citation30

Figure 1 MRI (FLAIR-weighted sequence) of a 76-year-old patient with chronic atrial fibrillation.

Abbreviations: FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

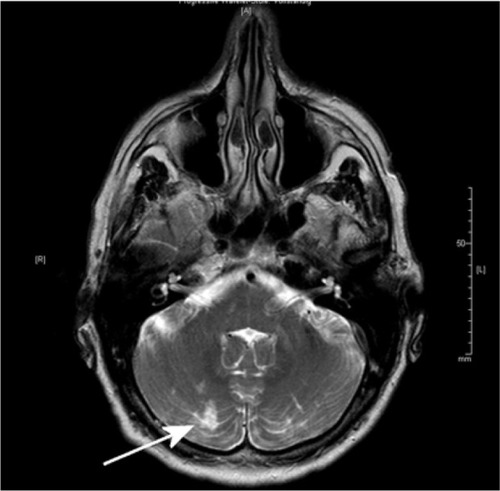

Figure 2 MRI of a 61-year-old patient with embolic silent brain infarction in cerebellum (arrow).

Abbreviation: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Most silent infarctions are localized in the subcortex.Citation33 Only 10% of infarctions are localized in the cortex.Citation26 Location of infarction could at least partly explain symptomatic versus covert lesions, because infarction in the internal capsule is associated with a higher probability of symptoms compared to those in other brain regions. Sizes of lacunas were not related to symptoms in studies.Citation20,Citation34 Valdés-Hernández et alCitation34 showed that the number of silent infarctions correlates with the risk of clinical stroke.Citation34

Risk factors for SCI

Data about risk factors are obtained from community-based samples. Risk factors with a strong association with SCI are age, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, carotid artery disease, and chronic kidney disease.Citation21,Citation35 The most clear risk factor is age. A meta-analysis by Fanning et alCitation21 showed an OR of prevalent SCI assessed per year of age ranging from 1.03 (95% CI: 0.98, 1.08) to 1.13 (95% CI: 1.09, 1.18) and per decade ranging from 2.44 (95% CI: 1.84, 3.23) to 3.21 (95% CI: 2.17, 4.74). Hypertension resulted in a microangiopathy of several organ systems. Chronic kidney disease and cerebral microangiopathy with lacunar infarction is the final common pathway of hypertension.Citation18

Other demographic characteristics and their risk for SCI are still in discussion: The Rotterdam Scan Study and the Cardiovascular Health Study identified a 30%–40% increased prevalence in females.Citation36,Citation37 Fukuda et alCitation38 showed a fourfold increased risk for SCI in early menopausal women. The majority of studies do not support any disparity between the sexes, so the effects of this factor remain unclear.Citation21

A low alcohol consumption is associated with a reduced risk of stroke morbidity and mortality.Citation39 Lee et alCitation40 (one or two times a week) and Mukamal et alCitation41 (one to six standard drinks per week) showed a protective effect for mild consumption. However, data are inconsistent. Data from Japan showed an increased risk of SCI associated with alcohol consumption, so perhaps ethnic differences in alcohol metabolism may play a role in the risk profile.Citation21,Citation42

There are only few studies showing a statistically significant association between smoking and SCI. Howard et alCitation43 showed in 1998 a relationship between exposure to cigarette smoke and SCI, in accordance to the higher incidence of carotid atheroscerlosis. In a cohort of 432 females, an association between “natural” early menopause and SCI was shown. Cigarette smoking, malnutrition, and lower socioeconomic status have been associated with earlier menopause.Citation38

Larger studies like the Rotterdam Study showed an association between the presence of diabetes mellitus and pack-years of smoking with symptomatic, but not with silent, infarcts.Citation44 In conclusion, the relevance of smoking remains unclear actually.

Abdominal obesity seems to be a risk factor for SBI too. Park et alCitation45 showed an increased risk for SCI for patients with a waist circumference ≥102 cm (male) or ≥88 cm (female). Studies analyzing body mass index data showed conflicting results. In a study by Bokura et al,Citation46 a body mass index ≥25 kg/m2 was accompanied with a higher risk for SCI. This study only included patients with a metabolic syndrome. Other studies could not confirm these results.Citation21,Citation47 In conclusion, an abdominal obesity in the context of a metabolic syndrome seems to be a more important risk factor than other forms of obesity.

SCIs – not so silent?

SCI can be seen as a part of cerebrovascular disease with a long-term worsening in brain function. Liebetrau et alCitation48 showed, in 2004, that almost one-fifth of 239 85-year-old participants have infarctions on CT, half of them had no clinical symptoms. These infarctions were related to an increased rate of dementia and 3-year mortality. Data from other large studies confirm these findings.Citation36,Citation49,Citation50

Patients recognizing stroke symptoms are a prerequisite to differentiate between SCI and TIA or stroke. A study of Howard et alCitation51 in 2006 including 18,462 participants without stroke anamnesis showed that 17.8% had in history one or more stroke symptoms after exact neurological anamnesis. Ethnic group, income, and educational level can influence detection of physical symptoms.Citation51 Furthermore, patients exclude symptoms, for example, for fear of severely diseases. Ritter et alCitation26 showed in their study that theoretical knowledge of symptoms and action knowledge were not found to be significantly associated with shorter prehospital times.

Data from Song et alCitation52 presented an increased severity of cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and SCI compared to patients with Alzheimer’s disease.Citation52

Yamashita et alCitation53 demonstrated in a long-term follow-up study that the presence of SCI was associated with a poor prognosis in geriatric depression compared with depressive patients without infarction. Similar to these findings, Fujikawa et alCitation54 showed that for late-onset mania beginning after age of 50, the incidence of SCI was significantly higher than that of patients with early-onset affective disorders (P<0.05).

Several studies showed an increased risk of stroke after detecting SCI or subcortical white matter lesions.Citation55–Citation57 To avoid stroke with severe functional impairment, an improved diagnosis with optimized scoring systems and optimized prevention treatment is necessary.Citation22,Citation58

SCI in AF

AF was identified as an independent predictor of SCI in a large autopsy study in Japan.Citation33 During the last decades, a couple of studies investigated the relationship between AF and the occurrence of SCI diagnosed by different methods of brain imaging. A large number of patients were evaluated using cranial CT. More than 2,000 probands were enrolled in diagnostic studies; SCI rates between 15% and 50% in AF patients were observed,Citation15,Citation59–Citation61 and a stroke rate of 7% during a follow-up period of 3 years in AF patients has been reported.Citation59 In collectives without a history of stroke and TIA, SCI prevalence was lower compared to collectives without exclusion of these high-risk patients. It seems that the influence of AF duration is not of clinical relevance; the prevalence between paroxysmal and chronic AF patients did not significantly vary.Citation61 Petersen et al were not able to show a higher SCI rate in patients with AF compared to patients without AF, but they found a significantly higher prevalence of regions with white matter tissue loss in AF patients compared to patients without AF.Citation61 Raiha et alCitation14 investigated the relationship between vascular factors and white matter low attenuation (WMLA) of the brain in CT and found a prevalence of WMLA of 73% in a small subgroup of 30 patients with AF compared to 48% in non-AF patients. In recent years, several studies investigated the relationship between SCI diagnosed by MRI and AF: The Framingham Offspring Study showed an increased risk of midlife SCI in patients with AF (OR 2.16) by MRI scan.Citation23 In dependence of different scan techniques and sequences and their specific image resolution, SCI rates in AF patients between 12.3% and 92% have been reported compared to rates between 17% and 69% in non-AF patients.Citation16,Citation62–Citation64 Gaita et alCitation13 found an SCI rate of 92% in patients with persistent AF, a rate of 89% in patients with paroxysmal AF, and a rate of 46% in patients without AF, and thus was also not able to show a relationship between SCI prevalence and AF duration.Citation13 In a subgroup of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, SCI rates of 61% in patients with silent AF were reported compared to 29% in patients without silent AF (P<0.01).Citation62,Citation65 Thus, the prevalence of SCI in AF patients is higher than in controls, albeit the prevalence varies widely between the different studies. The prevalence seems to be dependent on the sensitivity of the diagnostic tool and the comorbidities of the investigated collective. summarizes sample sizes and event rates of the different studies.

Table 1 Summary of SCI studies in patients with AF

Silent stroke and aortic or AF-related left atrial appendage abnormalities

The relationship between AF and SCI is not completely understood. Kobayashi et alCitation63 assumed a synergistic effect of microthrombi and hemodynamic abnormalities. In patients with AF, risk factors for clinically symptomatic thromboembolism have been identified: The SPAF III study identified left atrial abnormalities like a left atrial thrombus, spontaneous echo contrast (SEC), or an abnormal left atrial appendage (LAA) emptying velocityCitation66 and also aortic abnormalities like large (≥4 mm), ulcerated, or mobile plaques as risk factors for clinically symptomatic thromboembolisms, all investigated by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE).Citation66 However, the mechanisms leading to SCI in patients with nonvalvular AF are not well investigated. Very recently, one study investigated the role of left atrial or aortic abnormalities diagnosed by TEE in silent stroke: Sugioka et alCitation67 identified a higher prevalence of SCI in patients with left atrial abnormalities compared to patients without left atrial abnormalities (58% vs 22%; P<0.001) and in patients with complex arch plaques compared to patients without arch plaques (74% vs 20%; P<0.001). Left atrial abnormalities and complex arch plaques were independent risk factors of SBI.Citation67 Thus, abnormalities in the left atrium and complex arch plaques could play an important role in the occurrence of SCI. The authors only found a low prevalence of left atrial thrombus formation, but much higher rates of SEC or abnormal low emptying velocities in the LAA.Citation67 Some studies identified SEC as a risk factor of thromboembolism.Citation66,Citation68,Citation69 Possible mechanisms are an SEC-related fibrinogen-mediated erythrocyte aggregationCitation70 and microembolization of small thrombi arising in the fibrillating LAA.Citation13,Citation71

SCI related to AF ablation procedures

Pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) has become a standard therapeutic strategy in the treatment of symptomatic AF.Citation72 Complication rates of 3%–5% have been reported, with procedure-associated stroke being one of the most severe complications occurring in less than 1%.Citation73 A large survey of more than 1,000 procedures reported an occurrence of acute stroke in 0.6%.Citation74 The incidence of SCI varies widely more or less dependent of the ablation technology. Within the framework of studies, postablation MRI was performed in more than 1,700 patients and SCI/SCL rates of 12.6% were derived, with an estimated incidence of 9.3% after irrigated radiofrequency (IRF) ablation and of 20.9% using phased duty-cycled radiofrequency pulmonary vein ablation catheter (PVAC).Citation30 The largest group of SCL or SCE investigations were patients after IRF pulmonary vein ablation with rates between 7.4% and 24%;Citation75–Citation77 the incidence of FLAIR-independent SCE was reported between 6.8% and 24%,Citation78–Citation84 with lower incidence in patients under continued OAC.Citation81,Citation82 summarizes the incidence rates and study details.

Table 2 Summary of SCI studies after different ablation techniques of PVI

The number of investigated patients after PVAC procedure is quite smaller. In 2011, three independent studies reported incidence rates of SCE/SCL>35%.Citation75,Citation77,Citation79 Modifications in ablation procedure led to a significant reduction in SCE/SCL, with lowest rates in the ERACE trial ().Citation32,Citation85,Citation86 They revealed an incidence of only 1.7%, which is the lowest incidence rate of any ablation technology so far by three specific procedural changes: 1) the procedure was performed under heparin application (activated clotting time (ACT)>350 ms) and under continued OAC; 2) they minimized air ingress; and 3) they deactivated the distal or proximal electrode to avoid radiofrequency interaction.Citation86

The number of investigated patients after cryoballoon ablation is the smallest one compared to the previously reported ablation techniques, with an incidence of SCL/SCE of 14.5%.Citation30 SCL incidence rates were lowest after cryoballoon ablation, followed by IRF ablation and highest after PVAC ablation.Citation13,Citation75 Thus, all actually used ablation techniques of AF lead to an periprocedural occurrence of new SCI, but the clinical relevance of these lesions is unclear and not well investigated. summarizes the results of published studies.

The intraprocedural application of heparin to avoid thrombembolic complications monitored by measurements of ACT is recommended. One study identified ACT values >320 seconds as the only independent predictor of SCLs, an ACT increase of one point led to a reduction of stroke risk of 0.4%.Citation87 Another study reported a threefold increase in SCLs if only one ACT value of <300 seconds was measured.Citation76 They also identified the waiving of heparin bolus before transseptal punctuation as risk factor for SCL.Citation88 In contrast to this finding, a second study reported no influence of mean or minimal ACT on occurrence of SCI under continued intake of OAC.Citation81

A stable antithrombotic milieu during the ablation procedure is useful to avoid complication. Several studies reported lower periprocedural complication rates if OAC was continued.Citation89–Citation91 A couple of studies showed that continuation of OAC leads to lower SCL rates: Gaita et alCitation92 reported a more than threefold increased risk of SCL if INR values below 2.0 were measured. Comparable results were reported on continuation of rivaroxaban intake without an increase of bleeding complications.Citation93 In contrast to these findings, Martinek et alCitation81 concluded that continuation of OAC is not able to prevent cerebral embolism. Data of other direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) are sparse, but similar results as reported for rivaroxaban are hypothesized.

In fact, no periprocedural monitoring system for SCI exists; a few studies tried to detect periprocedural microembolic events by continuous registration of transcranial Doppler (TCD) signals, but a relationship between occurrence of periprocedural microembolic events in TCD and the detection of SCI in MRI after the procedure has not been reported yet.Citation30,Citation94 Kochhäuser et alCitation95 reported a significantly increased number of periprocedural microembolic events during PVI using PVAC compared to IRF procedure, but they were not able to detect any differences in neuropsychological assessment between the different ablation techniques, and they only found a subtle, diffuse postprocedural impairment of neuropsychological function depending on age and the number of detected microembolic events. Thus, the role of microembolic events as a potential cause of SCI remains unclear and actually not well investigated.

There is low evidence that waiving or postponing of periprocedural electrical cardioversion may decrease the rates of SCI,Citation92 but the majority of studies were not able to identify electrical cardioversion as a risk factor for SCI.Citation76,Citation78,Citation80,Citation96

Is there a need to reform anticoagulatory treatment regimes?

Kobayashi et alCitation63 showed in a patient group of 79 persons with AF that the CHADS2 score was associated with the number of SCIs in cortex/subcortex. There was no correlation with other infarct locations. Reviewed by Kalantarian et al,Citation29 data showed a twofold-increased risk in the odds of SCI.

Anticoagulation is able to reduce symptomatic stroke or TIA significantly in patients with AF. The impact on prevention of SCI is unclear. Further studies are necessary to find out whether anticoagulation influences SCI and identify patients who benefit from anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy.Citation29 There is low evidence that warfarin is not able to reduce brain volume loss in AF patients,Citation16 and differences in cognitive decline in AF patients between warfarin, aspirin, or no treatment could not be reported.Citation97 However, a statistically nonsignificant trend toward warfarin treatment versus aspirin in one studyCitation98 and a statistically nonsignificant trend toward OAC and decreased risk of dementia in another study have been reported.Citation99 Flaker et alCitation100 assumed that less effective OAC is associated with higher rates of cognitive decline and vascular events in patients with AF under OAC. Thus, DOACs with a higher time in therapeutic range compared to warfarin may prevent SCI.

On the other hand, it is not clearly defined if diagnosed SCI in cerebral asymptomatic AF patients should lead to an increase in CHA2DS2-VASc score of the subject, and thus this may result in a treatment with OAC only caused by diagnosis of SBI. Gaita et alCitation13 reported SCI rates approximately 90% in AF patients, while 60% of these patients had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of ≤1, and thus no general recommendation for OAC treatment.Citation13 If this therapy regime would prevent strokes in AF patients, MRI screening in AF patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of ≤1 should be discussed.

Conclusion

Studies showed that silent brain infarction correlate with impaired cognition, neurological deficits, and psychiatric disorder, as well as an increased risk of stroke. These suggest that these findings are neither silent nor innocuous.Citation101 Especially in elderly people, prevention strategies should be intensified, with a particular focus on the treatment of hypertensive microangiopathy to minimize the risk of eroding brain function and acute stroke.Citation22 Targeted education on the warning signs of stroke and risk factor reduction efforts for individuals who report stroke symptoms may be helpful in improving early recognition and in the prevention of stroke.Citation51

In studies, especially patients with AF had a higher rate of SCI and increased risk of stroke.Citation56,Citation102 A possible cause is a synergistic effect of microthrombi and hemodynamic abnormalities.Citation56 Importance of prophylactic anticoagulation to reduce the incidence of SCI is unclear because of less data.Citation29 Periprocedurally occurring SCIs are five to ten times more common than strokes. Consequences for patients are not sufficiently analyzed. Investigation in different interventional techniques is necessary to improve patient’s safety.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GoASHylekEMPhillipsKAPrevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) StudyJAMA2001285182370237511343485

- Lloyd-JonesDMWangTJLeipEPLifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart StudyCirculation200411091042104615313941

- MiyasakaYBarnesMEGershBJSecular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalenceCirculation2006114211912516818816

- BenjaminEJWolfPAD’AgostinoRBSilbershatzHKannelWBLevyDImpact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart StudyCirculation199898109469529737513

- HealeyJSConnollySJGoldMRSubclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of strokeN Engl J Med2012366212012922236222

- BornsteinNMAronovichBDKarepovVGThe Tel Aviv Stroke Registry: 3600 consecutive patientsStroke19962710177017738841327

- KaarisaloMMImmonen-RaihaPMarttilaRJAtrial fibrillation and stroke. Mortality and causes of death after the first acute ischemic strokeStroke19972823113159040681

- LinHJWolfPAKelly-HayesMStroke severity in atrial fibrillation. The Framingham StudyStroke19962710176017648841325

- MariniCDeSFSaccoSContribution of atrial fibrillation to incidence and outcome of ischemic stroke: results from a population-based studyStroke20053661115111915879330

- BenjaminEJLevyDVaziriSMD’AgostinoRBBelangerAJWolfPAIndependent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart StudyJAMA1994271118408448114238

- WolfPAAbbottRDKannelWBAtrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham StudyStroke19912289839881866765

- SamolAMasinMGellnerRPrevalence of unknown atrial fibrillation in patients with risk factorsEuropace201315565766223258819

- GaitaFCorsinoviLAnselminoMPrevalence of silent cerebral ischemia in paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation and correlation with cognitive functionJ Am Coll Cardiol201362211990199723850917

- RaihaITarvonenSKurkiTRajalaTSouranderLRelationship between vascular factors and white matter low attenuation of the brainActa Neurol Scand19938742862898503257

- KempsterPAGerratyRPGatesPCAsymptomatic cerebral infarction in patients with chronic atrial fibrillationStroke19881989559573400107

- StefansdottirHArnarDOAspelundTAtrial fibrillation is associated with reduced brain volume and cognitive function independent of cerebral infarctsStroke20134441020102523444303

- WilkeTGrothAMuellerSOral anticoagulation use by patients with atrial fibrillation in Germany. Adherence to guidelines, causes of anticoagulation under-use and its clinical outcomes, based on claims-data of 183,448 patientsThromb Haemost201210761053106522398417

- KimBJLeeSHPrognostic impact of cerebral small vessel disease on stroke outcomeJ Stroke201517210111026060797

- CaoLPokorneySDHaydenKWelsh-BohmerKNewbyLKCognitive function: is there more to anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation than stroke?J Am Heart Assoc201548e00157326240065

- FisherCMLacunes: small, deep cerebral infarctsNeurology19651577478414315302

- FanningJPWongAAFraserJFThe epidemiology of silent brain infarction: a systematic review of population-based cohortsBMC Med20141211925012298

- LongstrethWTJrDulbergCManolioTAIncidence, manifestations, and predictors of brain infarcts defined by serial cranial magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health StudyStroke200233102376238212364724

- DasRRSeshadriSBeiserASPrevalence and correlates of silent cerebral infarcts in the Framingham offspring studyStroke200839112929293518583555

- UeharaTTabuchiMMoriERisk factors for silent cerebral infarcts in subcortical white matter and basal gangliaStroke19993023783829933274

- VermeerSEDen HeijerTKoudstaalPJIncidence and risk factors of silent brain infarcts in the population-based Rotterdam Scan StudyStroke200334239239612574548

- RitterMABrachSRogalewskiADiscrepancy between theoretical knowledge and real action in acute stroke: self-assessment as an important predictor of time to admissionNeurol Res200729547647917535554

- MorrisZWhiteleyWNLongstrethWTJrIncidental findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysisBMJ2009339b301619687093

- LovbladKOLaubachHJBairdAEClinical experience with diffusion-weighted MR in patients with acute strokeAJNR Am J Neuroradiol1998196106110669672012

- KalantarianSAyHGollubRLAssociation between atrial fibrillation and silent cerebral infarctions: a systematic review and meta-analysisAnn Intern Med2014161965065825364886

- DenekeTJaisPScaglioneMSilent cerebral events/lesions related to atrial fibrillation ablation: a clinical reviewJ Cardiovasc Electrophysiol201526445546325556518

- BokuraHKobayashiSYamaguchiSDistinguishing silent lacunar infarction from enlarged Virchow-Robin spaces: a magnetic resonance imaging and pathological studyJ Neurol199824521161229507419

- WieczorekMHoeltgenRBrueckMDoes the number of simultaneously activated electrodes during phased RF multielectrode ablation of atrial fibrillation influence the incidence of silent cerebral microembolism?Heart Rhythm201310795395923567660

- ShinkawaAUedaKKiyoharaYSilent cerebral infarction in a community-based autopsy series in Japan. The Hisayama StudyStroke19952633803857886710

- Valdés-HernándezMDMaconickLCMunoz ManiegaSA comparison of location of acute symptomatic vs. “silent” small vessel lesionsInt J Stroke20151071044105526120782

- ToyodaGBokuraHMitakiSAssociation of mild kidney dysfunction with silent brain lesions in neurologically normal subjectsCerebrovasc Dis Extra201551222725873927

- VermeerSEPrinsNDdenHTHofmanAKoudstaalPJBretelerMMSilent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive declineN Engl J Med2003348131215122212660385

- SatoRBryanRNFriedLPNeuroanatomic and functional correlates of depressed mood: the Cardiovascular Health StudyAm J Epidemiol1999150991992910547137

- FukudaKTakashimaYHashimotoMUchinoAYuzurihaTYaoHEarly menopause and the risk of silent brain infarction in community-dwelling elderly subjects: the Sefuri brain MRI studyJ Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis201423581782224045081

- ZhangCQinYYChenQAlcohol intake and risk of stroke: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studiesInt J Cardiol2014174366967724820756

- LeeSJChoYJKimJGModerate alcohol intake reduces risk of ischemic stroke in KoreaNeurology201585221950195626519539

- MukamalKJLongstrethWTJrMittlemanMACrumRMSiscovickDSAlcohol consumption and subclinical findings on magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in older adults: the cardiovascular health studyStroke20013291939194611546878

- FukudaKYuzurihaTKinukawaNAlcohol intake and quantitative MRI findings among community dwelling Japanese subjectsJ Neurol Sci20092781–2303419059611

- HowardGWagenknechtLECaiJCooperLKrautMATooleJFCigarette smoking and other risk factors for silent cerebral infarction in the general populationStroke19982959139179596234

- VermeerSEKoudstaalPJOudkerkMHofmanABretelerMMPrevalence and risk factors of silent brain infarcts in the population-based Rotterdam Scan StudyStroke2002331212511779883

- ParkKYasudaNToyonagaSTsubosakiENakabayashiHShimizuKSignificant associations of metabolic syndrome and its components with silent lacunar infarction in middle aged subjectsJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200879671972118270234

- BokuraHYamaguchiSIijimaKNagaiAOguroHMetabolic syndrome is associated with silent ischemic brain lesionsStroke20083951607160918323475

- AonoYOhkuboTKikuyaMPlasma fibrinogen, ambulatory blood pressure, and silent cerebrovascular lesions: the Ohasama studyArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol200727496396817272746

- LiebetrauMSteenBHamannGFSkoogISilent and symptomatic infarcts on cranial computerized tomography in relation to dementia and mortality: a population-based study in 85-year-old subjectsStroke20043581816182015205488

- PrinsNDvan DijkEJden HeijerTCerebral white matter lesions and the risk of dementiaArch Neurol200461101531153415477506

- Saavedra PerezHCDirekNHofmanAVernooijMWTiemeierHIkramMASilent brain infarcts: a cause of depression in the elderly?Psychiatry Res2013211218018223154097

- HowardVJMcClureLAMeschiaJFPulleyLOrrSCFridayGHHigh prevalence of stroke symptoms among persons without a diagnosis of stroke or transient ischemic attack in a general population: the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) studyArch Intern Med2006166181952195817030827

- SongIUKimJSKimYIEahKYLeeKSClinical significance of silent cerebral infarctions in patients with Alzheimer diseaseCogn Behav Neurol2007202939817558252

- YamashitaHFujikawaTTakamiHLong-term prognosis of patients with major depression and silent cerebral infarctionNeuropsychobiology201062317718120664230

- FujikawaTYamawakiSTouhoudaYSilent cerebral infarctions in patients with late-onset maniaStroke19952669469497762043

- BokuraHKobayashiSYamaguchiSSilent brain infarction and subcortical white matter lesions increase the risk of stroke and mortality: a prospective cohort studyJ Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis2006152576317904049

- KobayashiSOkadaKKoideHBokuraHYamaguchiSSubcortical silent brain infarction as a risk factor for clinical strokeStroke19972810193219399341698

- VermeerSEHollanderMvan DijkEJSilent brain infarcts and white matter lesions increase stroke risk in the general population: the Rotterdam Scan StudyStroke20033451126112912690219

- CouttsSBEliasziwMHillMDAn improved scoring system for identifying patients at high early risk of stroke and functional impairment after an acute transient ischemic attack or minor strokeInt J Stroke20083131018705908

- EzekowitzMDJamesKENazarianSMSilent cerebral infarction in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. The veterans affairs stroke prevention in nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation investigatorsCirculation1995928217821827554199

- Silent brain infarction in nonrheumatic atrial fibrillationEAFT Study Group. European Atrial Fibrillation TrialNeurology19964611591658559367

- PetersenPMadsenEBBrunBPedersenFGyldenstedCBoysenGSilent cerebral infarction in chronic atrial fibrillationStroke1987186109811003686584

- NeumannTWojcikMBerkowitschACryoballoon ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: 5-year outcome after single procedure and predictors of successEuropace20131581143114923419659

- KobayashiAIguchiMShimizuSUchiyamaSSilent cerebral infarcts and cerebral white matter lesions in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillationJ Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis201221431031721111632

- ChenLYLopezFLGottesmanRFAtrial fibrillation and cognitive decline-the role of subclinical cerebral infarcts: the atherosclerosis risk in communities studyStroke20144592568257425052319

- MarfellaRSassoFCSiniscalchiMBrief episodes of silent atrial fibrillation predict clinical vascular brain disease in type 2 diabetic patientsJ Am Coll Cardiol201362652553023684685

- ZabalgoitiaMHalperinJLPearceLABlackshearJLAsingerRWHartRGTransesophageal echocardiographic correlates of clinical risk of thromboembolism in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation III investigatorsJ Am Coll Cardiol1998317162216269626843

- SugiokaKTakagiMSakamotoSPredictors of silent brain infarction on magnetic resonance imaging in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a transesophageal echocardiographic studyAm Heart J2015169678379026027615

- PepiMEvangelistaANihoyannopoulosPRecommendations for echocardiography use in the diagnosis and management of cardiac sources of embolism: European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) (a registered branch of the ESC)Eur J Echocardiogr201011646147620702884

- ChimowitzMIDeGeorgiaMAPooleRMHepnerAArmstrongWMLeft atrial spontaneous echo contrast is highly associated with previous stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation or mitral stenosisStroke1993247101510198322375

- RastegarRHarnickDJWeidemannPSpontaneous echo contrast videodensity is flow-related and is dependent on the relative concentrations of fibrinogen and red blood cellsJ Am Coll Cardiol200341460361012598072

- FeinbergWMSeegerJFCarmodyRFAndersonDCHartRGPearceLAEpidemiologic features of asymptomatic cerebral infarction in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillationArch Intern Med199015011234023442241443

- CammAJKirchhofPLipGYGuidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Eur Heart J201031192369242920802247

- CammAJLipGYDe CaterinaR2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm AssociationEur Heart J201233212719274722922413

- ArbeloEBrugadaJHindricksGESC-EURObservational Research Programme: the Atrial Fibrillation Ablation Pilot Study, conducted by the European Heart Rhythm AssociationEuropace20121481094110322628450

- Herrera SiklodyCDenekeTHociniMIncidence of asymptomatic intracranial embolic events after pulmonary vein isolation: comparison of different atrial fibrillation ablation technologies in a multicenter studyJ Am Coll Cardiol201158768168821664090

- Di BiaseLGaitaFTosoEDoes periprocedural anticoagulation management of atrial fibrillation affect the prevalence of silent thromboembolic lesion detected by diffusion cerebral magnetic resonance imaging in patients undergoing radiofrequency atrial fibrillation ablation with open irrigated catheters? Results from a prospective multicenter studyHeart Rhythm201411579179824607716

- GaitaFLeclercqJFSchumacherBIncidence of silent cerebral thromboembolic lesions after atrial fibrillation ablation may change according to technology used: comparison of irrigated radiofrequency, multipolar nonirrigated catheter and cryoballoonJ Cardiovasc Electrophysiol201122996196821453372

- WissnerEMetznerANeuzilPAsymptomatic brain lesions following laserballoon-based pulmonary vein isolationEuropace201416221421923933850

- DenekeTShinDIBaltaOPostablation asymptomatic cerebral lesions: long-term follow-up using magnetic resonance imagingHeart Rhythm20118111705171121726519

- RilligAMeyerfeldtUTilzRRIncidence and long-term follow-up of silent cerebral lesions after pulmonary vein isolation using a remote robotic navigation system as compared with manual ablationCirc Arrhythm Electrophysiol201251152122247481

- MartinekMSigmundELemesCAsymptomatic cerebral lesions during pulmonary vein isolation under uninterrupted oral anticoagulationEuropace201315332533123097222

- NeumannTKunissMConradiGMEDAFI-Trial (Micro-embolization during ablation of atrial fibrillation): comparison of pulmonary vein isolation using cryoballoon technique vs. radiofrequency energyEuropace2011131374420829189

- SchmidtBGunawardeneMKriegDA prospective randomized single-center study on the risk of asymptomatic cerebral lesions comparing irrigated radiofrequency current ablation with the cryoballoon and the laser balloonJ Cardiovasc Electrophysiol201324886987423601001

- LickfettLHackenbrochMLewalterTCerebral diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging: a tool to monitor the thrombogenicity of left atrial catheter ablationJ Cardiovasc Electrophysiol20061711716426390

- WieczorekMLukatMHoeltgenRInvestigation into causes of abnormal cerebral MRI findings following PVAC duty-cycled, phased RF ablation of atrial fibrillationJ Cardiovasc Electrophysiol201324212112823134483

- VermaADebruynePNardiSEvaluation and reduction of asymptomatic cerebral embolism in ablation of atrial fibrillation, but high prevalence of chronic silent infarction: results of the evaluation of reduction of asymptomatic cerebral embolism trialCirc Arrhythm Electrophysiol20136583584223983245

- ScaglioneMBlandinoARaimondoCImpact of ablation catheter irrigation design on silent cerebral embolism after radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: results from a pilot studyJ Cardiovasc Electrophysiol201223880180522494043

- AnselminoMScaglioneMDi BiaseLLeft atrial appendage morphology and silent cerebral ischemia in patients with atrial fibrillationHeart Rhythm20141112724120872

- PageSPSiddiquiMSFinlayMCatheter ablation for atrial fibrillation on uninterrupted warfarin: can it be done without echo guidance?J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol201122326527021040095

- GautamSJohnRMStevensonWGEffect of therapeutic INR on activated clotting times, heparin dosage, and bleeding risk during ablation of atrial fibrillationJ Cardiovasc Electrophysiol201122324825420812929

- GopinathDLewisWRDi BiaseLNataleAPulmonary vein antrum isolation for atrial fibrillation on therapeutic coumadin: special considerationsJ Cardiovasc Electrophysiol201122223623921044211

- GaitaFCaponiDPianelliMRadiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a cause of silent thromboembolism? Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of cerebral thromboembolism in patients undergoing ablation of atrial fibrillationCirculation2010122171667167320937975

- LakkireddyDReddyYMDi BiaseLFeasibility and safety of uninterrupted rivaroxaban for periprocedural anticoagulation in patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation: results from a multicenter prospective registryJ Am Coll Cardiol2014631098298824412445

- KissANagy-BaloESandorfiGEdesICsanadiZCerebral microembolization during atrial fibrillation ablation: comparison of different single-shot ablation techniquesInt J Cardiol2014174227628124767748

- KochhäuserSLohmannHHRitterMANeuropsychological impact of cerebral microemboli in ablation of atrial fibrillationClin Res Cardiol2015104323424025336357

- HaeuslerKGKochLHermJ3 Tesla MRI-detected brain lesions after pulmonary vein isolation for atrial fibrillation: results of the MACPAF studyJ Cardiovasc Electrophysiol2013241142122913568

- ParkHHildrethAThomsonRO’ConnellJNon-valvular atrial fibrillation and cognitive decline: a longitudinal cohort studyAge Ageing200736215716317259637

- MavaddatNRoalfeAFletcherKWarfarin versus aspirin for prevention of cognitive decline in atrial fibrillation: randomized controlled trial (Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study)Stroke20144551381138624692475

- BarberMTaitRCScottJRumleyALoweGDStottDJDementia in subjects with atrial fibrillation: hemostatic function and the role of anticoagulationJ Thromb Haemost20042111873187815550013

- FlakerGCPogueJYusufSCognitive function and anticoagulation control in patients with atrial fibrillationCirc Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes20103327728320233976

- PriceTRManolioTAKronmalRASilent brain infarction on magnetic resonance imaging and neurological abnormalities in community-dwelling older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study. CHS Collaborative Research GroupStroke1997286115811649183343

- HaraMOoieTYufuKSilent cortical strokes associated with atrial fibrillationClin Cardiol199518105735748785902

- RitterMADittrichRRingelsteinEBKlinisch stumme Hirninfarkte [Silent brain infarctions]Nervenarzt201182810431052 German21761183