Abstract

Background

Patients who have had a venous thromboembolic event are generally advised to receive anticoagulant treatment for 3 months or longer to prevent a recurrent episode. Current guidelines recommend initial heparin and an oral vitamin K antagonist (VKA) for long-term anticoagulation. However, because of the well-described disadvantages of VKAs, including extensive food and drug interactions and the need for regular anticoagulation monitoring, novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have become an attractive option in recent years. These agents are given at fixed doses and do not require routine coagulation-time monitoring. The NOACs are discussed in this review with regard to the needs of patients on long-term anticoagulation.

Methods

Current guidelines from Europe and North America that refer to the treatment of deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism are included, as well as published randomized Phase III clinical trials of NOACs. PubMed searches were used for sourcing case studies of long-term anticoagulant treatment, and results were filtered for human application and screened for relevance.

Conclusion

NOAC-based therapy showed a similar efficacy and safety profile to heparins/VKAs but without the need for regular anticoagulation monitoring or dietary adjustments, and can be taken as a fixed-dose regimen once or twice daily. This represents a significant step forward in facilitating the management of long-term anticoagulation therapy. Furthermore, in the EINSTEIN studies, improved patient satisfaction was documented with the NOAC rivaroxaban, which may result in better adherence to therapy and an overall reduction in the incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism.

Introduction

Patients who have had a venous thromboembolic event, that is, proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), are generally advised to receive anticoagulant treatment for a minimum of 3 months.Citation1,Citation2 The treatment period may be further extended, or even continued indefinitely, based on assessment of the individual’s risks of recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) and bleeding. The risk of secondary complications, such as post-thrombotic syndrome and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, may also have an impact on the prospective treatment duration. The periods of VTE treatment described by the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) are initial (the first ~7 days), long-term (~7 days to ~3 months), and extended (~3 months onward),Citation2 but many similar guidelines, such as those from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC),Citation1 simply categorize treatment as initial and long-term.

At present, there is no clear guidance on the optimal length of anticoagulant therapy for the prevention of recurrent VTE, except that the duration should be individualized based on the balance between the risks of a secondary event in patients who stop receiving anticoagulation and the risk of bleeding with continued therapy. Guidelines generally recommend initial treatment with parenteral unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or fondaparinux, overlapping with and transitioning to an oral vitamin K antagonist (VKA), such as warfarin, for long-term anticoagulation.Citation1,Citation2 This dual-drug approach is required because VKAs take several days to reach therapeutic levels of anticoagulation, as determined by the international normalized ratio (INR).Citation3 Regular coagulation-time monitoring and dose adjustments to maintain the INR in the therapeutic range of 2.0–3.0 are required for the duration of therapy, because the pharmacodynamic effects of VKAs are highly variable and affected by diet, medications, genetic polymorphisms, and other factors. In recent years, the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) dabigatran (a direct thrombin inhibitor) and rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban (direct Factor Xa inhibitors) have been developed as treatment alternatives to VKAs. They offer a more predictable pharmacological profile and can be given at fixed doses without the need for routine coagulation monitoring.Citation4 These agents have all undergone successful clinical trials for VTE treatment, given either as single-drug therapies (rivaroxaban, apixaban) or after initial parenteral anticoagulation (dabigatran, edoxaban). Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and, most recently, edoxaban are approved for the treatment of acute DVT and PE and prevention of recurrent VTE in the USA and European Union.

This review discusses the risk factors for VTE recurrence and treatment-associated bleeding, current guidelines, and clinical trial data on the use of NOACs for the treatment of acute DVT and PE and prevention of recurrent VTE, as well as the needs of patients on long-term anticoagulation. Case studies are included to illustrate situations in which patients may require long-term anticoagulation and how this can be managed.

Methods

Current European and North American guidelines for the treatment of DVT and/or PE were reviewed, along with published randomized Phase III clinical studies of NOACs. Case studies of long-term anticoagulant treatment were sourced via PubMed searches using the search strings [case AND warfarin AND cancer], [case AND PCC OR aPCC OR FVIIa AND reversal], and [case AND long-term anticoagulation AND X] in which X was replaced by cancer, antiphospholipid, antithrombin, Factor V Leiden, or protein C deficiency. Results were filtered to ensure that they were case reports and applied to humans and were further refined by a review of each abstract for relevance.

Balancing the risks of recurrent VTE and bleeding

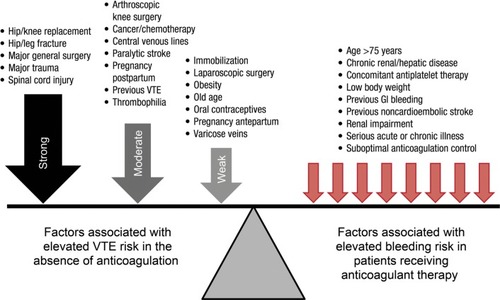

The risk of recurrent VTE increases when anticoagulation therapy is stopped, particularly if a patient has certain predisposing risk factors ().Citation1,Citation2 Risk factors for recurrent VTE include recent surgery and/or trauma, active cancer, advanced age, male sex, obesity, immobility, and thrombophilia. Some of these risk factors, such as surgery and immobility, may be reversible or transient, and it is unlikely that anticoagulation would be continued beyond the point at which the influence on VTE risk ceases. However, patients with a first unprovoked proximal DVT and/or PE, a second unprovoked VTE, or with ongoing comorbidities such as cancer may require long-term anticoagulation. The presence of residual vein thrombosis after initial anticoagulant treatment may be associated with an increased risk of recurrent DVT, although this is not clear.Citation5 In patients with a previous unprovoked VTE, the estimated risk of VTE recurrence was more than double for patients with elevated d-dimer levels compared with those with normal d-dimer levels, and recurrence may be particularly likely in men with high d-dimer levels.Citation6 However, the use of d-dimer testing to predict VTE recurrence is controversial. Genetic thrombophilia (eg, protein C, protein S, or antithrombin deficiency; prothrombin G20210A mutation; Factor V Leiden) can increase the risk of VTE recurrence, and patients with these mutations are therefore often recommended to receive lifelong anticoagulation ().Citation1,Citation2

Figure 1 The balance between the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding events.

Abbreviations: GI, gastrointestinal; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Table 1 Thrombophilia and development of thromboembolism

Several prediction models have been developed to attempt to quantify the most important risk factors for DVT recurrence. Rodger et al identified hyperpigmentation, edema/redness of the leg, d-dimer ≥250 µg/L while receiving anticoagulation, body mass index ≥30 kg/m2, and age ≥65 years as important factors for women with previous VTE and found that patients with two or more of these factors had a high risk of VTE recurrence.Citation7 The authors of the Vienna prediction model found that age, sex, location of VTE, body mass index, Factor V Leiden, prothrombin G20210A mutation, d-dimer concentration, and in vitro thrombin generation affected VTE recurrence rates, and they formulated a risk score accordingly.Citation8 The simple d-dimer, Age, Sex, Hormonal therapy (DASH) score assigns one point to each of the following: elevated d-dimer after stopping anticoagulation, age <50 years, male sex, and VTE not associated with hormonal therapy (for women). Patients with a score of 0 or 1 are at low risk of recurrence (3.1%/year), those with a score of 2 are at moderate risk (6.4%/year), and those with a score of 3 or above are at high risk (12.3%/year).Citation9 However, this scoring system requires further validation.

All anticoagulants carry a risk of bleeding owing to their mode of action. In addition, there are certain patient groups that are predisposed to an increased risk of bleeding when receiving anticoagulant treatment ().Citation2 These include elderly patients, those with renal impairment, patients with low body weight, and those with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding. Previous noncardioembolic stroke, chronic renal or hepatic disease, serious acute or chronic illness, and concomitant antiplatelet therapy are all also implicated as factors that increase the risk of bleeding. Patients who have poor anticoagulant control when receiving VKAs, which may be a result of suboptimal coagulation monitoring,Citation3 are also at elevated risk if their INR is persistently above the recommended upper boundary of 3.0.Citation2

Current guidelines on the duration of antithrombotic therapy

Current guidelines on the anticoagulant treatment of VTE are summarized in .Citation1,Citation2,Citation10 The ACCP recommends that patients with unprovoked DVT of the leg (isolated distal or proximal) or unprovoked but hemodynamically stable PE receive at least 3 months of anticoagulant treatment.Citation2 After 3 months, these patients should be evaluated for the risk and benefit of continued therapy. In patients with unprovoked VTE, extending anticoagulant therapy beyond 3 months is recommended only if the associated risk of bleeding remains low. In patients who experience DVT or PE and do not have cancer, VKAs are preferred to LMWH for long-term therapy, with LMWH as a second choice over NOACs (at the time the ACCP guidelines were issued, there was a considerably smaller body of published clinical data on NOACs than is now the case). In patients with DVT and cancer, LMWH is preferred, with VKAs as a second choice over NOACs.Citation2 LMWH is also indicated in pregnant women because it does not cross the placenta.Citation10

Table 2 The US and European guidelines on the duration of anticoagulant treatment for venous thromboembolism

Although the ESC guidelines deal primarily with PE, the recommendations are similar to those of the ACCP ().Citation1 In patients with a first unprovoked event and a low risk of bleeding, an indefinite duration of anticoagulant therapy is recommended provided that this is consistent with the patient’s preference. Most patients with a second unprovoked VTE are also recommended to receive indefinite anticoagulation.Citation1

Prevention of recurrent VTE with NOACS: evidence from Phase III clinical trials

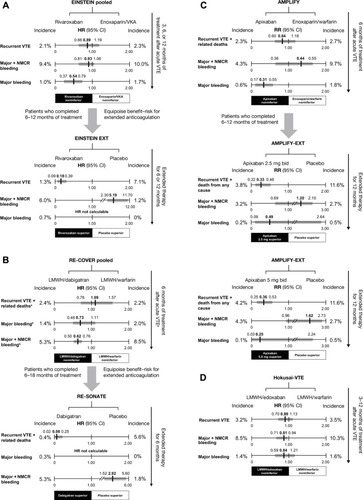

Randomized, controlled Phase III clinical trials have been conducted to investigate the NOACs rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, and dabigatran for the treatment of acute VTE for periods of up to 12 monthsCitation11–Citation16 and in extension studies for prevention of VTE recurrence for up to 3 years ().Citation11,Citation17,Citation18 A meta-analysis of the six acute treatment trials found a similar overall efficacy for the NOACs compared with standard therapy (relative risk =0.89; 95% confidence interval [CI] =0.75–1.05), whereas in the three studies of extended treatment, NOACs were superior to placebo for the prevention of recurrent VTE (relative risk =0.17; 95% CI =0.12–0.24).Citation19 In the EINSTEIN DVT and EINSTEIN PE studies, rivaroxaban 15 mg twice daily given for 21 days, followed by 20 mg once daily for 3 months, 6 months, or 12 months (depending on physician evaluation of risk factors), was noninferior to standard parenteral anticoagulation/VKA for the prevention of recurrent VTE (P<0.001 for noninferiority in both studies and a pooled analysis).Citation11,Citation12,Citation20 The EINSTEIN EXT study evaluated the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban for extended treatment of DVT (beyond the currently recommended treatment duration). Patients who had completed either the EINSTEIN DVT or EINSTEIN PE study or who had received VKA therapy outside of these trials for 6 months–12 months, and for whom the decision to stop or continue anticoagulation was at equipoise, were randomized to receive rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily or placebo for a further 6 months or 12 months.Citation11 Patients who received rivaroxaban had an 82% relative risk reduction for recurrent VTE compared with those in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

Figure 2 Principal efficacy and safety results of Phase III clinical trials of novel oral anticoagulants for the acute treatment of venous thromboembolism and long-term prevention of recurrence.

Abbreviations: bid, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; NMCR, nonmajor clinically relevant; RR, relative risk; VKA, vitamin K antagonist; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Similar to rivaroxaban, apixaban was also studied as a single drug for the treatment of VTE compared with standard dual-drug therapy. In the AMPLIFY study, patients with VTE received 6 months of treatment with apixaban (10 mg twice daily for 7 days, followed by 5 mg twice daily) or heparin/VKA; apixaban was noninferior to standard therapy for the prevention of recurrent VTE and VTE-related death (P<0.001 for noninferiority).Citation13 In AMPLIFY-EXT, patients who had completed AMPLIFY or had otherwise received 6 months–12 months of anticoagulant treatment, and for whom the decision to stop or continue anticoagulation was at equipoise, were randomized to apixaban 2.5 mg or 5 mg twice daily or placebo for a further 12 months. The lower and higher apixaban doses provided a respective 67% and 64% relative risk reduction for recurrent VTE plus all-cause mortality compared with placebo.Citation17

Unlike rivaroxaban and apixaban, edoxaban was evaluated against warfarin for the treatment of acute VTE after all patients had received initial heparin. In the Hokusai-VTE study, patients received 3 months–12 months of therapy according to physician assessment and local guidelines.Citation14 The edoxaban arm (60 mg once daily, or 30 mg once daily in patients with creatinine clearance [CrCl] 30 mL/min–50 mL/min, body weight ≤60 kg or receiving concomitant treatment with potent P-glycoprotein [P-gp] inhibitors) was noninferior to standard heparin/warfarin for the incidence of recurrent symptomatic VTE (P<0.001 for noninferiority). No extension study for edoxaban has yet been reported.

Dabigatran was evaluated in two studies for the treatment of acute VTE – RE-COVER and RE-COVER II – during which patients were randomized to receive dabigatran or VKA for 6 months.Citation15,Citation16 As in Hokusai-VTE, all patients received initial parenteral anticoagulation. Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was noninferior to VKA for the prevention of recurrent VTE and VTE-related death in a pooled analysis of the two studies (hazard ratio [HR] =1.09; 95% CI =0.76–1.57).Citation16 The RE-SONATE extension study with dabigatran had a similar design to EINSTEIN EXT and AMPLIFY-EXT: patients who had received 6 months–18 months of anticoagulation received a further 6 months of dabigatran 150 mg twice daily or placebo.Citation18 Dabigatran treatment led to a 92% relative risk reduction over placebo for the prevention of VTE or unexplained death (P<0.001). In a separate extension study, RE-MEDY, long-term dabigatran was compared with long-term warfarin and was noninferior for the incidence of recurrent or fatal VTE (P=0.01 for noninferiority).Citation18

As a result of these studies, the ESC now recommends apixaban (2.5 mg twice daily), rivaroxaban (20 mg once daily), and dabigatran (150 mg twice daily, or 110 mg twice daily for patients aged ≥80 years or those receiving concomitant verapamil treatment) as alternatives to VKA therapy (except for patients with severe renal impairment) if extended anticoagulation treatment is necessary (Class IIa B level of recommendation).Citation1

Managing the risk of bleeding complications with long-term or extended NOAC treatment

Bleeding risk and outcomes in clinical trials of NOACS

In general, results from the Phase III trials of NOACs suggest that the rate of clinically relevant bleeding is approximately 10% with 6 months–12 months of VKA therapy and is somewhat lower with NOACs (~4%–9%) ().Citation11–Citation16 In a meta-analysis of the acute treatment studies, the risk of major bleeding was significantly lower with the NOACs than standard therapy (relative risk =0.63; 95% CI =0.51–0.77) and was not significantly increased versus placebo in studies of extended therapy.Citation19 In the EINSTEIN DVT and EINSTEIN PE studies, major bleeding was defined as clinically overt and associated with a drop in hemoglobin levels of ≥2.0 g/dL, bleeding leading to the transfusion of ≥2 units of red cells, or bleeding occurring in a critical site (eg, intracranial or retroperitoneal) or contributing to death. Nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding did not meet the criteria outlined for major bleeding but was overt and associated with medical intervention, interruption or discontinuation of a study drug, unscheduled contact with a physician, or general discomfort or impairment in daily life.Citation11,Citation12 In the EINSTEIN pooled analysis, there was a similar incidence of major plus nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding with rivaroxaban compared with standard therapy (P=0.27); however, rivaroxaban was associated with a significant 46% relative reduction in the risk of major bleeding (HR =0.54; 95% CI =0.37–0.79; P=0.002).Citation20 In this pooled analysis, major bleeding was also relatively infrequent with rivaroxaban compared with standard therapy in some patient subgroups at high risk, including those defined as fragile (age >75 years, CrCl ≤50 mL/min, or weight ≤60 kg; HR =0.27, 95% CI =0.13–0.54, P=0.011), and patients with an extensive clot burden (HR =0.36, 95% CI =0.18–0.73),Citation20 suggesting a broader benefit of treatment with rivaroxaban in high-risk subgroups. In the EINSTEIN EXT study, four of the 598 patients receiving rivaroxaban who were evaluated for safety had major bleeding (versus none with placebo; P=0.11).Citation11 In AMPLIFY, the rates of major bleeding (0.6% vs 1.8%, P<0.001) and major plus nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding (4.3% vs 9.7%, P<0.001) were significantly lower with apixaban than with standard therapy,Citation13 whereas in AMPLIFY-EXT the rates of both these outcomes were low and similar to placebo.Citation17

In Hokusai-VTE, major bleeding occurred at a similar frequency in the edoxaban and standard therapy arms (P=0.35), whereas major plus nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding was significantly lower with edoxaban (P=0.004).Citation14 Broadly the same definitions for major and nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding as for the EINSTEIN studies applied to AMPLIFY and Hokusai-VTE.Citation13,Citation14 In the pooled RE-COVER and RE-COVER II analysis, major bleeding occurred with a similar incidence in the dabigatran and standard therapy arms (HR =0.73, 95% CI =0.48–1.11), whereas the incidence of major plus nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding was significantly reduced with dabigatran (HR =0.62, 95% CI =0.50–0.76).Citation16 In the pooled RE-COVER population, the risk of major bleeding with dabigatran compared with warfarin appeared to increase with advancing age (P=0.010 for interaction); overall, however, subgroup analyses showed that dabigatran had a consistent profile regardless of variations in patient demographics and risk factors.Citation16 In the extension studies, there were two major bleeding events with dabigatran in RE-SONATE, and although the incidence of major plus nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding was significantly higher than that with placebo (P=0.001), both major bleeding (P=0.06) and major plus nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding (P<0.001) were significantly lower with dabigatran than with warfarin in RE-MEDY.Citation18 In RE-COVER and the extension studies, the same definition was applied for major bleeding, whereas for nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding a slightly different list of criteria applied.Citation15,Citation18

Bleeding management and contraindications with NOACs

Suggested algorithms for the management of bleeding in patients receiving NOACs are available, and these are largely similar to the well-established protocols for conventional anticoagulants.Citation21,Citation22 However, the pharmacological characteristics of NOACs (summarized in ) provide particular advantages as well as challenges.Citation4,Citation14,Citation23–Citation26 Their short half-lives, for example (typically in the range of 5 hours–17 hours), are in contrast with the half-life of warfarin (mean =40 hours), meaning that temporary discontinuation may be sufficient to manage nonsevere bleeding. The plasma concentration of a NOAC may need to be measured in an emergency, for example, in cases of suspected overdose or serious bleeding, or when an urgent surgical procedure is required. Prolongation of a dilute thrombin time or ecarin clotting time assay may indicate clinically relevant dabigatran concentrations; an activated thromboplastin time assay may also provide a qualitative indication of dabigatran activity.Citation27 Specific and quantitative anti-Factor Xa assays exist for apixaban and rivaroxaban, but if these are unavailable, prolongation of a suitably sensitive prothrombin time test can qualitatively indicate the presence of rivaroxaban. (This assay is not suitable for apixaban).Citation27 Guidance for measuring edoxaban concentrations is currently lacking, but an anti-Factor Xa assay may be appropriate.

Table 3 Summary of pharmacological properties of novel oral anticoagulants

Clearance of a NOAC in a patient with renal impairment will take longer, particularly with dabigatran, which is largely dependent on renal elimination mechanisms. Dabigatran has a renal clearance of ~85%, whereas the values for apixaban and rivaroxaban range between 27% and 33%.Citation24–Citation26 Renal clearance of VKAs, by contrast, is minimal. For more severe bleeding, usual interventions such as mechanical compression (eg, in cases of epistaxis), fluid replacement, and use of blood products are suggested.Citation24–Citation26,Citation28–Citation30 Dabigatran can be dialyzed, but the other NOACs, because of their high protein binding, cannot. There is currently no specific reversal agent for any NOAC, although several are in development.Citation31,Citation32 Idarucizumab, a Fab fragment directed against dabigatran, is in Phase III trials and is likely to be the first such reversal agent approved for use.Citation33 Currently, if bleeding is considered life-threatening, nonspecific pro hemostatic agents, such as prothrombin complex concentrate, activated prothrombin complex concentrate, or recombinant Factor VIIa, may be used based on limited evidence, to be combined with emergency hemodynamic support ().Citation24–Citation26,Citation28–Citation30

Table 4 Reversal strategies for patients experiencing severe bleeding while receiving a novel oral anticoagulant

The likelihood of bleeding in relation to NOACs can be minimized by assessing each patient’s risk of bleeding and avoiding use in patients at known high risk of bleeding. These include patients with CrCl <15 mL/min (recommendations for patients with severe renal impairment [CrCl 15 mL/min–29 mL/min] vary by drug and region, but caution should be exercised even if it is permitted) or severe hepatic impairment (including cirrhotic patients with Child–Pugh score B or C).Citation24–Citation26,Citation28–Citation30 The presence of a lesion or condition causing a clinically significant risk of major bleeding, such as a current or recent gastrointestinal ulcer, malignant neoplasm, recent brain/spinal injury or surgery, ophthalmic surgery, or recent intracranial hemorrhage, is a contraindication to NOAC treatment.Citation24–Citation26,Citation28–Citation30 Additionally, NOACs should not be given in combination with other anticoagulants (except when switching between drugs), and concomitant use of antiplatelet agents or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increases the risk of bleeding. For rivaroxaban and apixaban, coadministration with strong inhibitors of both P-gp and cytochrome P450 3A4 is not recommended because these agents (mostly azole antimycotics and human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors) share the same major elimination pathways, which could lead to increased drug exposure and bleeding risk.Citation24,Citation25,Citation28,Citation29 Although not a cytochrome P450 3A4 substrate, dabigatran and its prodrug are P-gp substrates, meaning that concomitant administration with strong P-gp inhibitors can lead to clinically relevant increases in dabigatran concentrations.Citation26,Citation30 Edoxaban clearance is also affected by concomitant strong P-gp inhibitors.Citation34

In all cases, the balance between the risk of bleeding and risk of VTE should be the primary factor for deciding whether to give an anticoagulant and for determining the duration of treatment.

Patient needs in long-term or extended anticoagulation

Patients requiring long-term or extended anticoagulation may find some of the limitations associated with VKA therapy, particularly regular coagulation monitoring and dietary restrictions, inconvenient in their daily lives.Citation4 In addition to benefits in terms of reduced risk of major bleeding, the NOACs are not subject to these limitations and, therefore, simplify long-term treatment. With rivaroxaban, this has been shown to correlate with a 27% reduction in hospital admissions compared with standard LMWH/VKA treatment for patients with DVT,Citation35 and a US model has shown that NOACs are cost saving for VTE treatment compared with standard therapy.Citation36 Patient-reported outcomes including treatment satisfaction were assessed in the EINSTEIN DVT and EINSTEIN PE studies, by using the newly developed and validated Anti-Clot Treatment Scale (ACTS). A greater treatment satisfaction was reported in the rivaroxaban groups of both studies. In EINSTEIN DVT, the mean ACTS Burdens scores were found to be 55.2 versus 52.6 (P<0.0001), and overall mean ACTS Benefits scores 11.7 versus 11.5 (P=0.006), for rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin/VKA, respectively.Citation37 A similar trend was seen in the PE population: mean ACTS Burdens scores were found to be 55.4 versus 51.9 (P<0.0001), and mean ACTS Benefits scores were 11.9 versus 11.4 (P<0.001).Citation38 The improved patient satisfaction with rivaroxaban reported in these studiesCitation37,Citation38 is likely to have a positive impact on adherence to therapy.Citation37,Citation38 The use of once-daily regimens for long-term therapy also appears to encourage adherence compared with more frequent dosing.Citation39 This, in turn, could reduce not only the risk of recurrent VTE but also the likelihood of long-term complications that can have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life ().

Table 5 Warfarin drug interaction in cancer therapy

Conclusion

To reduce the risk of recurrent VTE and its associated complications, many patients will require long-term or even extended anticoagulation therapy. The limitations of traditional heparin and VKA treatment can be a burden for patients and physicians, but the development of NOACs that are both effective and potentially reduce bleeding risk substantially reduces the impact of long-term anticoagulation. The extension studies for the NOACs showed that a significant residual risk of VTE remained after 6 months–12 months of VKA therapy. Patients who received rivaroxaban or apixaban showed a significant risk reduction for recurrent VTE compared with those receiving placebo. Study outcomes suggest that current recommendations for 3 months or >3 months of therapy could be revised to address the high residual risk of VTE that remains after 6 months–12 months of therapy with VKAs.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Jasmina Saric, who provided editorial assistance with funding from Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals and Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Disclosure

The author declares no conflicts of interest in this work, and received no funding for it.

References

- KonstantinidesSVTorbickiAAgnelliG2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolismEur Heart J2014353033306925173341

- KearonCAklEAComerotaAJAmerican College of Chest PhysiciansAntithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelinesChest2012141e419Se494S22315268

- AgenoWGallusASWittkowskyACrowtherMHylekEMPalaretiGOral anticoagulant therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelinesChest2012141e44Se88S22315269

- EikelboomJWWeitzJINew anticoagulantsCirculation20101211523153220368532

- CarrierMRodgerMAWellsPSRighiniMLe GalGResidual vein obstruction to predict the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with deep vein thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Thromb Haemost201191119112521382171

- DouketisJTosettoAMarcucciMPatient-level meta-analysis: effect of measurement timing, threshold, and patient age on ability of d-dimer testing to assess recurrence risk after unprovoked venous thromboembolismAnn Intern Med201015352353120956709

- RodgerMAKahnSRWellsPSIdentifying unprovoked throm-boembolism patients at low risk for recurrence who can discontinue anticoagulant therapyCMAJ200817941742618725614

- EichingerSHeinzeGJandeckLMKyrlePARisk assessment of recurrence in patients with unprovoked deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism: the Vienna prediction modelCirculation20101211630163620351233

- TosettoAIorioAMarcucciMPredicting disease recurrence in patients with previous unprovoked venous thromboembolism: a proposed prediction score (DASH)J Thromb Haemost2012101019102522489957

- BatesSMGreerIAMiddeldorpSVeenstraDLPrabulosAMVandvikPOVTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelinesChest2012141e691Se736S22315276

- The EINSTEIN InvestigatorsOral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med20103632499251021128814

- The EINSTEIN–PE InvestigatorsOral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolismN Engl J Med20123661287129722449293

- AgnelliGBullerHRCohenAAMPLIFY InvestigatorsOral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med201336979980823808982

- The Hokusai-VTE InvestigatorsEdoxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med20133691406141523991658

- SchulmanSKearonCKakkarAKDabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med20093612342235219966341

- SchulmanSKakkarAKGoldhaberSZRE-COVER II Trial InvestigatorsTreatment of acute venous thromboembolism with dabigatran or warfarin and pooled analysisCirculation201412976477224344086

- AgnelliGBullerHRCohenAAMPLIFY-EXT InvestigatorsApixaban for extended treatment of venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med201336869970823216615

- SchulmanSKearonCKakkarAKRE-SONATE Trial InvestigatorsExtended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolismN Engl J Med201336870971823425163

- KakkosSKKirkilesisGITsolakisIAEditor’s Choice – efficacy and safety of the new oral anticoagulants dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban in the treatment and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of phase III trialsEur J Vasc Endovasc Surg20144856557524951377

- PrinsMHLensingAWBauersachsREINSTEIN InvestigatorsOral rivaroxaban versus standard therapy for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism: a pooled analysis of the EINSTEIN-DVT and PE randomized studiesThromb J2013112124053656

- SiegalDMCrowtherMAAcute management of bleeding in patients on novel oral anticoagulantsEur Heart J20133448949823220847

- HeidbuchelHVerhammePAlingsMEuropean Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of new oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillationEuropace20131562565123625942

- ZahirHMatsushimaNHalimABEdoxaban administration following enoxaparin: a pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic, and tolerability assessment in human subjectsThromb Haemost201210816617522628060

- Bayer Pharma AGXarelto® (rivaroxaban) Summary of Product Characteristics2015 Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000944/WC500057108.pdfAccessed June 9, 2015

- Bristol-Myers Squibb PfizerEliquis® (apixaban) Summary of Product Characteristics2014 Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002148/WC500107728.pdfAccessed April 28, 2015

- Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbHPradaxa® (dabigatran etexilate) Summary of Product Characteristics2015 Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000829/WC500041059.pdfAccessed April 28, 2015

- BlannADLipGYLaboratory monitoring of the non-vitamin K oral anticoagulantsJ Am Coll Cardiol2014641140114225212649

- Janssen Pharmaceuticals IncXarelto® (rivaroxaban) Prescribing Information2015 Available from: http://www.xareltohcp.com/sites/default/files/pdf/xarelto_0.pdfAccessed June 9, 2015

- Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Pfizer IncEliquis® (apixaban) Prescribing Information2014 Available from: http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_eliquis.pdfAccessed April 28, 2015

- Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals IncPradaxa® (dabigatran etexilate) Prescribing Information2015 Available from: http://bidocs.boehringer-ingelheim.com/BIWebAccess/ViewServlet.ser?docBase=renetnt&folderPath=/Prescribing%20Information/PIs/Pradaxa/Pradaxa.pdfAccessed April 28, 2015

- SchieleFvan RynJCanadaKA specific antidote for dabigatran: functional and structural characterizationBlood20131213554356223476049

- LuGDeGuzmanFRHollenbachSJA specific antidote for reversal of anticoagulation by direct and indirect inhibitors of coagulation Factor XaNat Med20131944645123455714

- PollackCVJrReillyPABernsteinRDesign and rationale for RE-VERSE AD: a phase 3 study of idarucizumab, a specific reversal agent for dabigatranThromb Haemost201511419820526020620

- MikkaichiTYoshigaeYMasumotoHEdoxaban transport via P-glycoprotein is a key factor for the drug’s dispositionDrug Metab Dispos20144252052824459178

- MerliGJHollanderJELefebvrePRates of hospitalization among patients with deep vein thrombosis before and after the introduction of rivaroxabanHosp Pract19952015438593

- AminABrunoATrocioJLinJLingohr-SmithMReal-world medical cost avoidance when new oral anticoagulants are used versus warfarin for venous thromboembolism in the United StatesClin Appl Thromb Hemost Epub2015519

- BamberLWangMYPrinsMHPatient-reported treatment satisfaction with oral rivaroxaban versus standard therapy in the treatment of acute symptomatic deep-vein thrombosisThromb Haemost201311073274123846019

- PrinsMBamberLCanoSWangMLensingABauersachsRPatient-reported treatment satisfaction with oral rivaroxaban versus standard therapy in the treatment of acute symptomatic pulmonary embolismBlood2012120 Abstract 1163

- LalibertéFBookhartBKNelsonWWImpact of once-daily versus twice-daily dosing frequency on adherence to chronic medications among patients with venous thromboembolismPatient2013621322423857628

- CitroRPanzaABottiglieriGSurgical treatment of impending paradoxical embolization associated with pulmonary embolism in a patient with heterozygosis of Factor V LeidenJ Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown)20131474574720639767

- CookRMRondinaMTHortonDJRivaroxaban for the long-term treatment of spontaneous ovarian vein thrombosis caused by Factor V Leiden homozygosityAnn Pharmacother2014481055106024798316

- JukicITitlicMTonkicARosenzweigDCerebral venous sinus thrombosis as a recurrent thrombotic event in a patient with heterozygous prothrombin G20210A genotype after discontinuation of oral anticoagulation therapy: how long should we treat these patients with warfarin?J Thromb Thrombolysis200724778017245631

- KimDILeeBBNohSIConservative management of superior mesenteric and portal vein thrombosis associated with protein C and S deficiencyInt Angiol1997162352389543219

- KshatriyaSVillarrealDLiuKAngina pectoris in a patient with protein C deficiency and deep vein thrombosis: thrombus versus myxoma?Catheter Cardiovasc Interv20127929129321523888

- DumkowLEVossJRPetersMJenningsDLReversal of dabigatran-induced bleeding with a prothrombin complex concentrate and fresh frozen plasmaAm J Health Syst Pharm2012691646165022997117

- JavedaniPPHorowitzBZClarkWMLutsepHLDabigatran etexilate: management in acute ischemic strokeAm J Crit Care20132216917623455868

- MolinaMHillardVHFeketeRIntracranial hemorrhage in patient treated with rivaroxabanHematol Rep20146528324711920

- LakatosBStoeckleMElziLBattegayMMarzoliniCGastrointestinal bleeding associated with rivaroxaban administration in a treated patient infected with human immunodeficiency virusSwiss Med Wkly2014144w1390624452338

- GonzvaJPatricelliRLignacDSpontaneus splenic rupture in a patient treated with rivaroxabanAm J Emerg Med20143295024612597

- OnodaSMitsufujiHYanaseNDrug interaction between gefitinib and warfarinJpn J Clin Oncol20053547848216006576

- SaifMWWasifNInteraction between capecitabine and gemcitabine with warfarin in a patient with pancreatic cancerJOP2008973974318981557