Abstract

Background

Totally laparoscopic aortobifemoral bypass (LABF) procedure has been shown to be feasible for the treatment of advanced aortoiliac occlusive disease (AIOD). This study compares the LABF with the open aortobifemoral bypass (OABF) operation.

Methods

In this prospective comparative cohort study, 50 consecutive patients with type D atherosclerotic lesions in the aortoiliac segment were treated with an LABF operation. The group was compared with 30 patients who were operated on with the OABF procedure for the same disease and time period. We had an explanatory strategy, and our research hypothesis was to compare the two surgical procedures based on a composite event (all-cause mortality, graft occlusion, and systemic morbidity). Stratification analysis was performed by using the Mantel–Haenszel method with the patient–time model. Cox multivariate regression method was used to adjust for confounding effect after considering the proportional hazard assumption. Cox proportional cause-specific hazard regression model was used for competing risk endpoint.

Results

There was a higher frequency of comorbidity in the OABF group. A significant reduction of composite event, 82% (hazard ratio 0.18; 95% CI 0.08–0.42, P=0.0001) was found in the LABF group when compared with OABF group, during a median follow-up time period of 4.12 years (range from 1 day to 9.32 years). In addition, less operative bleeding and shorter length of hospital stay were observed in the LABF group when compared with the OABF group. All components of the composite event showed the same positive effect in favor of LABF procedure.

Conclusion

LABF for the treatment of AIOD, Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus II type D lesions, seems to result in a less composite event when compared with the OABF procedure. To conclude, our results need to be replicated by a randomized clinical trial.

Background

The main goal of laparoscopic abdominal aortic surgery is not only to provide long-term graft patency and limb salvage rate equivalent to an open abdominal aortic surgery, but also provide the advantages of a minimally invasive procedure.Citation1–Citation4 Numbers of laparoscopic aortic procedures, vascular surgeons, and vascular centers performing laparoscopic aortic surgery are steadily increasing.Citation3,Citation5

Despite technical advancement and experience within the endovascular procedures, the long-term results of aortobifemoral bypass (ABFB) for the treatment of advanced atherosclerotic lesions in the aortoiliac segment still remain superior.Citation6–Citation9 Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus (TASC) II recommends open surgery as the primary treatment for type D lesions (TASC II).Citation10

Since the last decade, time and again, the feasibility of the totally laparoscopic aortobifemoral bypass (LABF) procedure has been proven.Citation1–Citation4,Citation11 In this article, we present our experience with the LABF operation for the treatment of advanced aortoiliac occlusive disease (AIOD) and TASC II type D lesions. We also present the comparative results between LABF and open aortobifemoral bypass (OABF) for the treatment of the same disease.

Methods

The study was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics of Oslo University and also registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01259908). Informed written consent was obtained from all patients before operation.

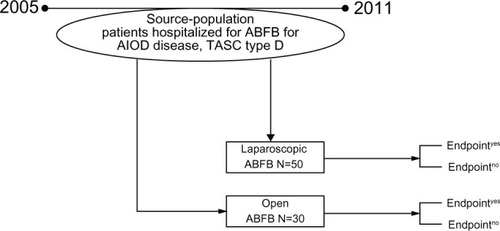

This is a prospective and a comparative cohort study with analysis of different outcomes after LABF and OABF (). Eighty consecutive patients with TASC II type D lesions were operated with ABFB at the Oslo University Hospital, Aker, Norway, between November 2005 and December 2011. The closing date of the study was on May 15, 2015. Fifty patients underwent LABF and the rest OABF. summarizes the clinical characteristics of the patients in the two arms of the cohort.

Figure 1 Flow chart of the comparative cohort study. Laparoscopic aortobifemoral bypass versus open aortobifemoral bypass during the period 2005–2011.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of the patients operated either with totally laparoscopic aortobifemoral bypass (LABF) or with open aortobifemoral bypass (OABF) during the period 2005–2011

The major endpoint was the composite event, defined as the first event of a combined incidence of all-cause mortality, graft thrombosis, and systemic morbidity. Systemic morbidity was defined as non-fatal damage or disease with an impact on health that is related to the procedure and involves any organ or tissue other than the peripheral arterial system or surgical wound.Citation12 Mortality and graft thrombosis were excluded from this definition. Whereas, the secondary endpoints such as operation time, operative bleeding, and total hospital stay were considered.

The atherosclerotic lesion in the aortoiliac segment was classified according to the TASC II.Citation10 Patients with TASC II type D lesions, not amenable to or with a previously unsuccessful endovascular treatment, were only chosen for surgery. The patients were preoperatively investigated with magnetic resonance angiography. Computed tomography was performed to assess the extent of aortic calcification as well as to identify retroaortic localization of the left renal vein.

The main indication for surgery was debilitating intermittent claudication in all patients, defined as a maximum pain-free walking distance of <200 m (Rutherford’s category 3).Citation12 Two patients in the LABF and five patients in the OABF group also had rest pain and/or concomitant ischemic wound (Rutherford’s category 4 and 5).

Patients with previous multiple major abdominal surgery were not offered laparoscopic surgery (n=3), they underwent open surgery. However, previous appendectomy, cholecystectomy, gastrectomy, or surgery in the pelvic region was not considered a contraindication for a totally laparoscopic procedure. The operation-related variables were compared in the two arms of the cohort.

Epidemiological design and statistical methods

We had an explanatory strategy, and our research hypothesis was to compare the two surgical procedures. Survival freedom from composite event as well as for the individual components, namely mortality, graft thrombosis, and systemic mortality was presented. Comparison of survival curves was done with the help of the log-rank test.Citation13

Stratification analysis was performed by using the Mantel–Haenszel method with the patient–time model to quantify the confounders and to detect the effect modifiers.Citation14

For the primary endpoint and its components, adjusted effect was obtained by using Cox regression model with a manual backward elimination procedure. The adequacy of the proportional hazard was checked with the test of scaled Schoenfeld residuals. A test of interaction using the log likelihood ratio was done when using the Cox model.Citation15

Mortality was considered as a competing risk variable for the outcomes, graft thrombosis, and systemic complications. Being an explanatory strategy, cause-specific regression model for hazard function need to be used, for competing risk endpoint instead of the Fine and Gray regression model.Citation16

Linear regression model was utilized to control the confounding effect for the secondary continuous outcomes. Stata 13.1 was used for the statistical analysis.

Results

Composite endpoint and its components

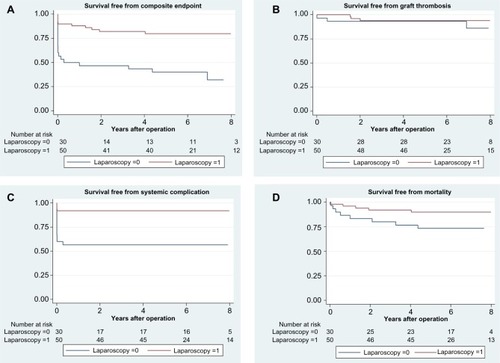

Survival freedom from composite event showed a 5-year survival of 79.4% (SE 5.85%) for LABF versus 37.5% (SE 9.3%) for OABF, and a significant difference (P=0.00001) for the log-rank test (). The survival freedom from the individual components of the composite endpoint showed a better survival result for LABF when compared with OABF with a significant log-rank test, except for graft thrombosis ( and ).

Figure 2 Survival analysis.

Table 2 Effect of procedure on composite outcome and its components, using the patient–time model

Adjusted effect

The median follow-up time was 4.12 years (range from 1 day to 9.3 years). presents the crude as well as the adjusted effect of operation type on the composite endpoint as well as on the individual components of the composite endpoint. Adjusted Cox’s model for the composite endpoint was hazard ratio of 0.18 (95% CI 0.08–0.42; P=0.0001), when controlling for age and suprarenal cross-clamping (). This indicates an 82% relative reduction of composite events in the laparoscopic procedure group when compared with the open surgery, for a median follow-up time of 4.12 years.

Table 3 Crude effect of laparoscopic aortobifemoral bypass versus open aortobifemoral bypass

Another analysis was done on different components of composite endpoint controlling for the different confounders. The beneficial effect of LABF was detected on all of the individual components with borderline significance for the incidence of graft thrombosis (due to limited power) ().

Secondary endpoints

Median operation time was 265 minutes versus 214 minutes, in LABF and OABF, respectively (P=0.003). The median aorta clamping time was 59.5 minutes versus 36.5 minutes, in the LABF and OABF, respectively (P=0.001). The aortic clamping time was defined as the time taken to construct the proximal anastomosis. The results of operation-related data in the two groups are presented in .

The patients in the LABF group had a significantly less operative bleeding (P=0.0001), when compared with the OABF (). LABF was totally laparoscopic in 43 (86%) patients. All patients received an end-to-side, proximal anastomosis, except in two cases where, due to small aortic aneurysms, an end-to-end anastomosis was performed. Conversion to laparotomy and consequently, open ABFB was done in seven (14%) patients. Of these, six conversions were among the first half of laparoscopic cohort. Heavily calcified infrarenal aorta (n=3), uncontrolled bleeding from a left retroaortic renal vein (n=1), and failure of the technical instrument (n=2) were the reasons for conversion to laparotomy. All patients in the OABF group (n=30) underwent median laparotomy, and the infrarenal aorta was approached by free dissecting the peritoneum just to the left side of duodenum. In case of suprarenal cross-clamping (nine cases), pre-aortic left renal vein was mobilized and aorta was cross-clamped just superior to the renal arteries. The median suprarenal cross-clamping time was 1 minute (range 1–3 minutes). After the removal of the atherosclerotic plaque, the suprarenal clamp was replaced with an infrarenal cross-clamp before aortic anastomosis.

Most of the patients in the LABF were mobilized, and normal food intake could be initiated a day after surgery. Intensive ward stay and hospital stay were significantly shorter for the patients operated with the laparoscopic technique, 5 versus 11 days (P=0.0002) ().

Discussion

In this study, the results showed 82% relative reduction of the composite event (all-cause mortality, graft occlusion, and systemic morbidity) in the patients operated with LABF when compared with the OABF procedure during a median follow-up time period of 4.12 years. This reduction has a relatively huge impact and a clear tendency recommending LABF for the treatment of AIOD.

According to a document released by the Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products under The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, the use of a composite endpoint in clinical research is usually justified, if the following assumptions are respected:

The individual components of the composite endpoint are clinically meaningful and of similar importance to the patient.

The expected effects on each component are similar, based on the biological plausibility.

The clinically more important components of composite endpoint should at least not be affected negatively.

Consequently, the regulatory authorities will analyze separately all components of a composite endpoint. One needs to be aware whether a treatment affects all components or just a single outcome.Citation17

We used the composite endpoint as our primary endpoint, because the cohort is small, and the composite endpoint increases the statistical precision as well as the efficiency of the analysis.Citation18 We chose the outcomes, which were only clinically meaningful and of similar importance to the patient. As there can be a competing risk between the individual components of the composite endpoint, so we performed the competing risk analysis and found that graft thrombosis and the systemic complications also individually have the same effect as the composite endpoint in favor of LABF. This confirms the validity of the individual components of the composite endpoint. As studying non-fatal events without including death is methodologically invalid, we included mortality as the third component of composite endpoint in our study.Citation19 illustrates the survival freedom from the individual components of the composite endpoint.

A substantial amount of evidence about the feasibility of LABF procedure for the treatment of AIOD has been presented since the introduction of this relatively minimally invasive procedure.Citation1–Citation3,Citation11,Citation20 However, the general acceptance and the adoption of the laparoscopic procedure by the vascular surgeons have been very poor. A general conception about the LABF, as a technically demanding procedure and a fear of inducing complications during the period of learning curve, might have been a reason for the delayed propagation of LABF procedure.Citation3,Citation21 However, it is a fact that none of the published series has indicated more complications with LABF when compared with the OABF procedure.Citation1–Citation5 Besides, one has to take into account the retrospective nature of many of the earlier results of the OABF procedure.Citation22

Fourneau et alCitation23 have shown that the learning curve for the LABF procedures is approximately 25 operations. Our main challenge was that very few patients with the TASC II type D lesions were suitable for surgery.

Although we had three of the total seven conversions due to the aortic calcification, we do not consider circumferential aortic wall calcification as a contraindication to the LABF procedure, as long as it is possible to achieve the suprarenal aortic cross-clamping.Citation2 Besides, conversion to laparotomy is not considered as a failure of operative treatment.Citation24

Operation time and aortic cross-clamping time, in accordance with the other published series, are longer in the LABF procedure, but they have no significant confounding effect on the mortality and morbidity.Citation1–Citation5 Shorter intensive post-stay, early mobilization, and discharge from the hospital advocate for LABF bypass as a procedure of choice for the patients with TASC II type D lesions.

Recently, a very first study of the direct comparison of LABF with the OABF for the treatment of AIOD was published.Citation5 Although the study shows less bleeding, shorter hospital stay, and fewer complications in the laparoscopic procedure, it does not define primary and secondary endpoints. Besides, the variability of observation time and the confounding effects of different variables in the two procedures have not been analyzed. Only one randomized controlled trial comparing the LABF and OABF has been published, but, unfortunately, it was abandoned prematurely, and hence it lacks statistical power to properly address the matters of morbidity and mortality.Citation25 There is a need for comparative cohort studies and especially, potential randomized controlled trials to conclusively answer the questions.

Published results of LABF and our own findings in this study may confirm that the LABF has become a standard procedure for the treatment of advanced AIOD in the dedicated institutes.Citation26 The main goal of the laparoscopic aortic surgery in future studies should be reviewed, and it should rather be an achievement of less mortality and morbidity when compared with open surgery.

Conclusion

Totally LABF for the treatment of AIOD, TASC II type D lesions, seems to result in less composite event when compared with open surgery. To conclude, our results need to be replicated by a randomized clinical trial.

Author contributions

SSHK contributed to conception and design; all authors collected data; SSHK and MA analyzed and interpreted the data, and performed statistical analysis; all authors drafted and critically reviewed the article; SSHK, MA, and JJJ approved the final version of the article; SSHK held the overall responsibility for this study. All authors have approved the final version.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely thankful for the kind assistance of Dr Marc Coggia, in guiding and providing his expert assistance for the initial LABF procedures in this study. We are also extremely thankful for the constructive criticisms and a continuous support of our colleagues at the Department of Vascular Surgery, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway as well as the nursing staff at the surgical section.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DionYMGriselliFDouvilleYLangisPEarly and mid-term results of totally laparoscopic surgery for aortoiliac disease: lessons learnedSurg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech200414632833415599296

- CoggiaMJaverliatIDi CentaITotal laparoscopic bypass for aortoiliac occlusive lesions: 93-case experienceJ Vasc Surg200440589990615557903

- CauJRiccoJBCorpatauxJMLaparoscopic aortic surgery: techniques and resultsJ Vasc Surg2008486 Suppl37S44S discussion 5S18945578

- KazmiSSHSundhagenJOFlørenesTLKroeseAJJørgensenJJLaparoskopisk aortakirurgiTidsskr Nor Lægeforen20071271115181520

- BrulsSQuaniersJTrommePComparison of laparoscopic and open aortobifemoral bypass in the treatment of aortoiliac disease. Results of a contemporary series (2003–2009)Acta Chir Belg20121121515822442910

- KashyapVSPavkovMLBenaJFThe management of severe aortoiliac occlusive disease: endovascular therapy rivals open reconstructionJ Vasc Surg2008486145114571457.e1e318804943

- TsetisDUberoiRQuality improvement guidelines for endovascular treatment of iliac artery occlusive diseaseCardiovasc Intervent Radiol200831223824518034277

- PulliRDorigoWFargionAEarly and long-term comparison of endovascular treatment of iliac artery occlusions and stenosisJ Vasc Surg2011531929820934841

- KimTHKoYGKimUOutcomes of endovascular treatment of chronic total occlusion of the infrarenal aortaJ Vasc Surg20115361542154921515016

- NorgrenLHiattWRDormandyJANehlerMRHarrisKAFowkesFGInter-society consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASC II)J Vasc Surg200745Suppl SS5S6717223489

- KolvenbachRPuerschelAFajerSTotal laparoscopic aortic surgery versus minimal access techniques: review of more than 600 patientsVascular200614418619217026908

- RutherfordRBBakerJDErnstCRecommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: revised versionJ Vasc Surg19972635175389308598

- KleinbaumDGKleinMSurvival Analysis: A Self-learning Text3rd edNew YorkSpringer2011

- KleinbaumDGKupperLLMorgensternHEpidemiologic Research: Principles and Quantitative MethodsNew YorkJohn Wiley and Sons1982

- KirkwoodBREssentials of Medical StatisticsCarlton, VICBlackwell Science Ltd2003

- WolbersMKollerMTStelVSCompeting risks analysis: objectives and approachesEur Heart J201435422936294124711436

- Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP)Points to Consider on Multiplicity Issues in Clinical TrialsLondonThe European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products Available from http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003640.pdfAccessed July 1, 2015

- FreemantleNCalvertMWoodJEastaughJGriffinCComposite outcomes in randomized trials: greater precision but with greater uncertainty?J Am Med Assoc20032891925542559

- SkaliHSolomonSDPfefferMAAre we asking too much of our trials?Am Heart J200214311311773904

- NioDDiksJBemelmanWAWisselinkWLegemateDALaparoscopic vascular surgery: a systematic reviewEur J Vasc Endovasc Surg200733326327117127084

- AlimiYSMouretFGariteyVRieuRLaparoscopic aortic surgery: recent development in instrumentationSurg Technol Int20051425326116525981

- de VriesSOHuninkMGResults of aortic bifurcation grafts for aortoiliac occlusive disease: a meta-analysisJ Vasc Surg19972645585699357455

- FourneauILerutPSabbeTHouthoofdSDaenensKNevelsteenAThe learning curve of totally laparoscopic aortobifemoral bypass for occlusive disease. How many cases and how safe?Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg200835672372918294873

- FourneauIMarienIRemyPConversion during laparoscopic aortobifemoral bypass: a failure?Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg201039223924519892572

- TiekJRemyPSabbeTLaparoscopic versus open approach for aortobifemoral bypass for severe aorto-iliac occlusive disease – a multicentre randomised controlled trialEur J Vasc Endovasc Surg201243671171522386382

- McKinlayJBFrom “promising report” to “standard procedure”: seven stages in the career of a medical innovationMilbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc19815933744116912389