Abstract

Digital dermatitis (DD) is a multifactorial polymicrobial infectious disease originally described in dairy cattle, but is increasingly recognized in beef cattle, sheep, and more recently, elk and goats. Clinical bovine lesions typically appear on the plantar surface of the hind foot from the interdigital space and heel bulb to the accessory digits, with a predilection for skin–horn junctions. Lesions present as a painful ulcerative acute or chronic inflammatory process with differing degrees of severity. This variability reflects disease progression and results in a number of different clinical descriptions with overlapping pathologies that ultimately have a related bacterial etiology. The goal of this review article is to provide a concise overview of our current understanding on digital dermatitis disease to facilitate clinical recognition, our current understanding on the causative agents, and recent advances in our understanding of disease transmission.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Clinical presentation of digital dermatitis (DD) in ruminants

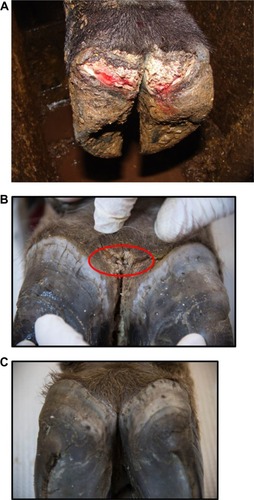

A typical active lesion associated with bovine digital dermatitis (BDD) is found on the plantar surface of the hind foot of a dairy cow that presents as a circumscribed moist ulcerative erosive mass along the coronary band or interdigital space ().Citation1 Lameness is likely, as lesions are painful upon palpation and prone to bleeding when touched. Histologically, there is a loss of stratum corneum, epidermal hyperplasia, and reactive inflammation. Whilst the precise etiology of such lesions is not yet clear, it is apparent that treponemes are the major pathogenic bacteria detected in a series of related lesions associated with the bovine hoof.Citation2 Further, it is increasingly apparent that such lesions are not restricted to bovines, and that treponemes (as well as other bacterial agents) are associated with a similar range of lesions that are increasingly observed in other ruminant species including sheep, elk and goats.Citation3–Citation5 Given that those treponemes associated with bovine digital dermatitis are genetically similar to those observed in contagious ovine digital dermatitis, hoof disease in elk, and severe lameness in goats, which occupy the same anatomical site, these diseases are not mutually exclusive. Collectively, they provide a greater insight to understand the range of clinical manifestations of digital dermatitis in large and small ruminants, as well as pathogenic mechanisms of infection that will facilitate an improved understanding of disease transmission, treatment, and prevention.

Figure 1 Bovine digital dermatitis.

In 1974, Cheli and MortellaroCitation6 described a bovine digital dermatitis in Italy that affected 60%–70% of cows. A similar disease of the bovine hoof was reported shortly thereafter by Rebhun et al,Citation7 in the US; interdigital papillomatosis was characterized by circular, edematous proliferative masses, and interdigital growths that caused severe lameness in approximately 70% of cows. The short disease transmission period was indicative of an infectious agent but preparation of an autogenous formalinized vaccine created from papillomas of the herd did not alter disease nor prevent recurrence. Whilst histopathology suggested that papillomas were of viral origin, no virus was identified by culture or electron microscopy.Citation7 By mid-1980, similar clinical signs were routinely recognized on dairy farms throughout Europe and the US, and referred to by a range of names including digital dermatitis, interdigital dermatitis, interdigital papillomas, Mortellaro’s disease, hairy heel warts, and strawberry foot. Digital dermatitis and interdigital dermatitis are suggested to be the same disease, differing only by location of lesion.Citation8 Digital dermatitis is a global disease that is estimated to cost the US $190 million per annum due to lameness associated with decreased milk yield.Citation9

Although digital dermatitis was initially described as causing acute lameness, further studies have demonstrated that lesions develop through different stages which have been characterized grossly.Citation10–Citation13 At the macroscopic level, a qualitative classification system has been developed to identify the different levels of BDD lesion progression;Citation14 Class I (M1) refers to the early stage of digital dermatitis which is a small circumscribed granulomatous area that is moist, ragged, mottled red-gray, 0.5–2 cm in diameter, and lies at the epithelial surface or up to 2 mm underneath it. Class II (M2) refers to the classical ulceration close to the coronary band, >2 cm in diameter, with granulomatous tissue where the lesion lies more than 2 mm underneath the epithelial layer. Class III (M3) refers to the healing process of the M2 lesion which is covered by a scab. Class IV (M4) lesions may be observed as the disease becomes endemic in herds and presents as an alteration of the skin close to the coronary band. Class IV (M4) refers to a hyperkeratotic lesion with a proliferative aspect varying in appearance from papilliform to mass-like projections. M4 has been further subdivided to include M4.1 that recognizes M4 with a small active painful M1 focus ().Citation15 The early stages of lesion development (M1) have also been further subdivided to recognize the transition from normal skin (stage 0) to initial onset (stage 1) and developing lesions (stage 2). Stage 2 is further classified as a “type A” lesion if presenting in the interdigital space and has a more ulcerated appearance in comparison to a “type B” lesion which develops more diffusely across the heel with a thickened, crusted appearance.Citation11 The morphological characteristics of lesions are not always easy to distinguish and can be interrelated or concurrent and the etiopathogenesis of the conditions may overlap. Whilst a specific lesion may be painful upon palpation, not all affected animals will be clinically lame.

Histopathologically, lesions are classified as bovine digital dermatitis if they comprise 1) a circumscribed plaque of eroded acanthotic epidermis attended by para keratotic papillomatous proliferation colonized by spirochetes (treponemes), 2) loss of stratum granulosum, 3) invasion of stratum spinosum by spirochetes and 4) infiltration of neutrophils, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils in dermis.Citation1,Citation16 Histological activity can be focal, segmental, or continuous. Early stage lesions tend to be described as hyperkeratotic, acanthotic with surface hemorrhage and erythrocytic crusts, whereas developing and end-stage lesions have segmental localized necrotizing to necrosuppurative epidermitis with individual cell necrosis, ballooning degeneration of epithelial cells, necrotizing vasculitis, and intralesional bacteria including spirochetes. There is no clear indication of the rate of development of lesions; transition between disease states is reported to range from as few as 12 days to as long as 135 days with an upper limit of almost 2 years.Citation11,Citation17,Citation18 However, such variation likely reflects how often and thoroughly that lesions are inspected.

Heel horn erosion, also known as slurry-heel or heel necrosis, is defined as “an irregular loss of bulbar horn” and associated with an unhygienic environment since manure and urine induce structural breakdown of the horn tissue. Dermatitis at the skin-horn junction can result in changes in growth of the horn leading to deterioration. There is a strong association between the presence of heel horn erosion and digital dermatitis, and spirochetes (treponemes).Citation2 Heel horn erosion has other environmental causes and different histological presentations, however the damaged tissue may provide the ideal microenvironment for invading treponemes thus disposing the animal to concurrent hoof conditions.Citation19

Digital dermatitis has the same clinical presentation in beef cattle as it does in dairy cattle with similar predisposing factors, with the inclusion of potential introduction by contact with dairy animals (introduction of dairy-type steers at a feedlot, contact at livestock shows, etc). Whilst the prevalence of BDD in beef cattle does not approach the level seen in dairy cattle, it is being recognized more readily in recent years.Citation20,Citation21

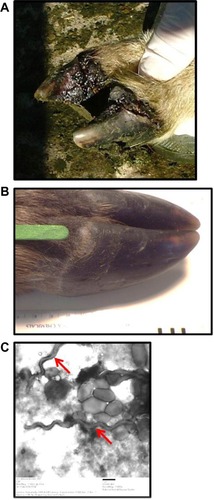

In 1997, a severe virulent footrot was first described in sheep that failed to respond to formalin or zinc sulfate footbaths.Citation3,Citation22 Clinical presentation differed from ovine footrot as it was characterized by severe inflammatory lesions of the coronary bands which progressed to detachment of the hoof capsule. As with bovine digital dermatitis, it is evident that treponemes are a major bacterial component. Contagious Ovine Digital Dermatitis (CODD) is an emerging disease that has now become common in the UK. It is important to note that whilst detailed histological studies of lesions of CODD have not yet been completed, CODD is regarded as a distinct disease to that of ovine footrot or ovine interdigital dermatitis; this is evidenced by the failure of sheep with CODD to respond to treatments associated with footrot. Whilst treponemes were not originally identified in cases of ovine footrot and digital dermatitis, this should be reevaluated in light of improving culture and molecular techniques.Citation23

The continued association of treponemes with lameness in hooved animals has also been documented during the emergence of abnormal hooves and lameness in a population of free-ranging Roosevelt elk in the US in 2008. Similar clinical presentation to CODD was observed including inflammatory lesions along the coronary band resulting in hoof sloughing, heel bulb ulceration and hyperplasia. Initial histological evaluations revealed alterations in the dermal structure similar to BDD.Citation5 As with CODD and BDD, treponemes were identified within the lesions.Citation4 No underlying systemic or bone related diseases were detected. Finally, treponemes were identified and cultured from the first reported cases of a “severe lameness problem” in a UK dairy goat herd.Citation6 Collectively, these reports indicate that any cloven hoofed ruminant is susceptible to digital dermatitis, including domestic beef and dairy cattle, sheep, goats, and wild elk.Citation4

Pathogens associated with digital dermatitis

Although no definitive etiological agent has yet been identified, it is clear that viral or fungal pathogens are not associated with DD.Citation7,Citation11,Citation24 Further, DD is a polybacterial disease as evidenced by the detection of multiple different bacterial agents associated with clinical lesions, and their improved resolution in response to antibiotics. Whilst multiple bacterial agents have been routinely identified and cultured from active DD lesions, the most common bacteria associated with BDD and CODD are multiple phylotypes from the genus Treponema; phylotypes (PT) are defined as clusters of treponemes whose 16S rDNA sequence differs by ∼2% from known species and are ≥99% similar to other members of their cluster.Citation25 Finally, the evidence suggests that treponemes cultured from lesions associated with digital dermatitis have genetic similarities, whether they are identified in different countries, on different continents, or whether they are associated with bovine, ovine, cervine or caprine lesions.

The diversity and dynamics of treponemes and other bacterial agents associated with lesion progression in a closed bovine herd was recently characterized by high throughput DNA sequencing technologies.Citation11 Of note, the bacterial microbiota of biopsies taken from lesions at different stages were statistically different, and as the lesion progressed, the abundance of Spirochaetaceae increased such that they accounted for 94.3% of sequences derived from a chronic lesion. All species of the family Spirochaetaceae were identified as belonging to the genus Treponema, containing 45 unique species of which 12 were predominant.Citation11 These results confirm an array of previous studies which conclude that DD lesions are associated with multiple phylotypes of treponemes.Citation2,Citation26,Citation27 Prevalence of the different phylotypes differs according to stage of lesion development as well as the location within the lesion. Multiple phylotypes of treponemes, identified by in situ hybridization, have been shown to be highly invasive with multiple different phylotypes detected in the same lesion.Citation27 No individual phylotypes could be associated with a specific colonization pattern or type of lesion.Citation28 Treponemes have also been detected in hair follicles and sebaceous glands, a possible route of entry.Citation29

Despite their abundance, only a handful of treponemes have been successfully cultured to date. These include representatives of several clusters such as 1) T. medium/T. vincentii-like, 2) T. phagedenis-like, and 3) T. putidum/T. denticola-like which are grouped according to 16S rDNA and flaB2 gene homology. The first group is similar to T. vincentii, a pathogen associated with human periodontal disease whilst the second group of T. phagedenis-like treponemes is reported to be the one and same as the human genitalia commensal bacteria T. phagedenis.Citation30 Human and bovine isolates of T. phagedenis from the US, the UK, and Sweden have >98% identical 16S rDNA sequence, similar enzyme activity profiles, growth tolerances, and physical appearance. The third group of T. putidum/T.denticola-like treponemes is now recognized as the unique species of T. pedis.Citation31 All three groups have been cultured from lesions derived from cattle, sheep, elk and goats.Citation22,Citation32

Whilst no single phylotype dominates all lesions, T. phagedenis has been cultured from all stages of lesion development. It is hypothesized that different phylotypes dominate the lesion at different stages;Citation27 treponemes dominating the early lesions most resembled uncultured, unidentified T. refringens-like PT1, PT2, PT3 (T. calligyrum-like) and a novel genomospecies closely related to T. refringens.Citation11 In contrast, T. medium, T. pedis/PT8 and T. denticola were the most common treponeme operational taxonomic units identified in mature or chronic lesions. Multiple phylotypes (mean ranges from 7 to 15) are typically identified in each lesion.Citation25,Citation27,Citation33

Whilst much has been made of the association of treponemes with DD lesions, it is theorized that a number of other bacteria are required to facilitate skin colonization, lesion development, and chronicity.Citation2,Citation27 Much of this evidence comes from the culture of these organisms along with treponemes from lesions, microscopic examination of the lesions (histologic evaluation, fluorescent in situ hybridization), and metagenomic sequencing. These findings are summarized in . Further evidence for their role in BDD includes the antibody response seen in cattle with active or recent BDD in which higher levels of reactive IgG to antigens from Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium, and Dichelobacter are detected (Wilson-Welder, unpublished data).Citation34 The role of these bacteria as primary pathogens or secondary colonizers is not clear; the high prevalence of Dichelobacter in healthy feet indicates that D. nodusus alone is less likely to cause disease.Citation2 However D. nodusus produces extracellular proteases assumed to be associated with tissue damage and can be readily codetected with treponemes in cows with interdigital dermatitis and heel horn erosion, and thus is hypothesized to act in synergy with treponemes to initiate bovine and ovine digital dermatitis.Citation2,Citation27,Citation35,Citation36 In support of this, a lower prevalence of Dichelobacter was identified in chronic lesions compared to acute lesions. This is not without precedent as D. nodusus and Fusobacterium necrophorum act synergistically to cause ovine footrot.

Table 1 Bacterial genera associated with digital dermatitis in ruminant species

Treponemes associated with DD induce a humoral and cell mediated immune response. Serum antibody reacts with great affinity to whole-cell sonicates of treponemes isolated from lesions.Citation37–Citation41 Several researchers have attempted to use this as a predictor of animal exposure or digital dermatitis lesion status.Citation42–Citation44 The general conclusion is that serology is not suitable as a complete replacement for visual inspection of the hoof in bovine digital dermatitis, and has limited application to making herd level decisions. There is a wide range in response due to individual animal variability within groups demonstrating active lesions, recovered lesions, and among naïve groupings.Citation39,Citation44 The variable antibody response to treponemes also was observed in Washington elk (Wilson-Welder, unpublished data). Part of this variability may be explained by the different phylotypes of treponemes found in the DD lesions and the hypothesis that these populations shift over timeCitation11 and are spatially distributed within the lesion,Citation45 and thus provide little or limited contact with the host immune system. Further theories as to the variability of the antibody response include potential immunological tolerance as treponemes are part of the normal intestinal flora,Citation46,Citation47 along with the variable nature of the DD treponemes themselves. Research demonstrated few cross-reacting epitopes amongst DD treponemes.Citation40

Studies into the cell-mediated immune response elicited by BDD or CODD are limited. Studies using a bovine macrophage cell line incubated with a T. phagedenis isolated from BDD (Iowa strain 1A) showed increased expression of genes regulated by NFκB and other cell signaling associated molecules, increased expression of apoptosis associated molecules (BCL-2), downregulation of immune modulation pathways, antigen presentation, and cytoskeletal rearrangement, and wound healing pathways.Citation48 This represents a single cell type interacting with a whole cell sonicate of a single bacterium present in the BDD lesion, giving just a small snapshot of the complexity of host–pathogen cross talk. In another study, analysis of total RNA transcripts in BDD lesions and normal skin with pathway analysis software indicated no activation or suppression of local immune response.Citation49 Molecular signaling pathways increased in BDD lesions over normal skin include IL1β, a cytokine involved in early initiation of inflammation, and matrix metallopro-teinase 13 which is secreted by many cell types and is key to tissue matrix remodeling. Interestingly, the expression of genes encoding keratin and keratin-associated proteins were downregulated in BDD.Citation49 Cellular proliferation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) occurred when they were incubated with treponemal antigen, a large percentage of which were γσ-Tcells.Citation40 Whilst treponeme whole cell sonicate induced host inflammatory mediators in bovine foot skin fibroblasts, no significant changes were observed in bovine foot keratinocytes.Citation50

Current understanding of disease transmission

The broad role of biosecurity has importance in prevention of transmission of infectious disease, including prevention of the spread of digital dermatitis.Citation51 With herds without history of the disease, one should be aware of the status of herds from which replacements are sourced, whether the carrier employed has transported animals with digital dermatitis, and the handling of replacements upon arrival using quarantine housing. There is also a risk of transmission of DD from the comingling of sheep and cattle.Citation35 The use of hoof trimmers is of benefit in preventing and controlling lameness in general, and improved conformation provides increased resistance to DD;Citation52 however, a recent study has indicated the presence of treponeme DNA on trimming equipment, including isolation of a T. phagedenis-like isolate from a trimming knife after trimming an affected cow.Citation53 Disinfection of the equipment resulted in decreased detection of DNA and negative culture, emphasizing the need for cleaning between animals and between farms to avoid inadvertent spread of the disease. As is frequently the case with biosecurity, the impact of available resources, personnel, time, and the perception of impact frequently affect implementation of control measures as well as the design and implementation of quarantine and elimination plans.Citation35,Citation52,Citation54–Citation57

The source of treponemes involved in DD has been examined with indications that environmental slurry and cow feces may serve as a source of exposure,Citation58 with the oral cavity, colon, and rectum indicated as potential sites of colonization.Citation46 However, of the >20 phylotypes of treponemes associated with BDD, none are considered part of the normal microbiota of the bovine gastrointestinal tract.Citation58 Additionally, phylotypes associated with BDD were identified at such a low prevalence rate in feces and environmental slurry that their biological significance remains to be validated. Nevertheless, poor leg cleanliness is consistently associated with increased risk of DD.

Control measures should focus not only on limiting exposure to known risk factors, but also on curing existing DD lesions. The speed of detecting acute lesions and efficiency of treatment were key parameters in whether they became more severe or not. A fast transition from an acute lesion to a healing lesion is achieved by promoting early treatment, whilst a delayed transition from a healing lesion to an acute lesion is achieved by efficient footbath protocol.Citation59 The persistence of treponemes in treated or resolving lesions may act as a continued source of infection; a foot initially observed with a chronic DD lesion which was considered “cured” was more likely to develop active DD than a foot initially free of DD. This may allow treponemes to persist at both the animal and herd level, despite the use of topical treatments, potentially contributing to the high recurrence rates (54%) observed. Topical treatments may only be useful in particular settings as spirochetes are not completely eradicated from the surface of lesions after treatment, such that relapses occur at 5–7 weeks when treated with a single topical application of oxytetracycline.Citation13,Citation15,Citation60,Citation61 Additional studies may shed further light on this possibility and could indicate the need to consider systemic treatments, as recognized for the treatment of CODD.Citation36 In a study evaluating the timing of initial clinical disease, it was found that heifers experiencing DD prior to first calving were prone to develop recurrent lesions in subsequent lactations. This suggested a chronic infection status with the potential for transmission to susceptible herd mates, a possibility hinted at as well by the high level of recurrence rates (33%) observed.Citation1,Citation62

Numerous studies have been conducted to examine risk factors for DD; these include an association between disease expression and age at first calving, housing type, days in milk, parity, herd size, type of land cows access on a daily basis, flooring type where lactating cows walked, percent of cows born off the operation, use of a primary hoof trimmer, and lack of washing of trimming equipment between cows, and genetic contribution.Citation64–Citation66 Recent observations of the presence of DD Treponema spp. in association with other forms of lameness which were clinically characterized as nonhealing including toe necrosis, sole-ulcer, and white line disease, suggest the potential for colonization of physically compromised hoof tissues.Citation67 These sites represent regions beyond those normally associated with DD lesions. The authors proposed a potential for these treponemes, on DD endemically affected farms, to play a role in the development of the nonhealing state.Citation67 Similar organisms have been observed in multiple ulcerative lesion sites in different species (sheep,Citation68 swine,Citation69–Citation71 horses,Citation72–Citation75 and cattleCitation20), and their detection now in other non-infectious hoof diseases speaks to the opportunistic behavior demonstrated in affecting compromised tissues, and the ability of these treponemes to exacerbate different clinical issues.

Considerations to further understand the disease process of DD

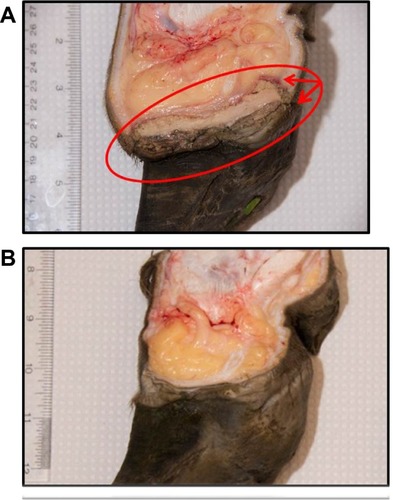

Typical lesions associated with DD in bovines, ovines, and cervines are shown in and . Generally, bovine lesions are visually assessed, and 3–5 mm biopsies are taken for more detailed culture and histopathological studies, as in the area circled in , a lesion that was positive for the presence of spirochetes (Wilson-Welder, data not shown). However, further examination of the lesion highlighted in is provided in , which shows the extent of the lesion when visualized after dissecting between the bovine digits. Results illustrate a lesion that extends throughout the entire interdigital space and several millimeters below the skin surface.

Figure 2 Ovine and cervine digital dermatitis.

Figure 3 Bovine digital dermatitis.

BDD is a relatively novel disease that has rapidly emerged to be a leading cause of bovine lameness. Although significant progress has been made in identifying many of the clinical signs associated with BDD as well as lesion development, there is very little understanding on the initiation of the primary acute lesion and the complete resolution (if any) of a treated chronic lesion. Visual inspection is not sufficient as a means of detecting the early stages of lesion development, and the topical application of treatments to lesions such as that illustrated in is not sufficient to clear infection. The presence of layers of proliferative skin on DD lesions could have major implications for how infectious bovine lameness affects and stays endemic in modern herds.Citation42 Our understanding of CODD, elk hoof disease and severe lameness in goats is even less and little, if any, data is available on lesion initiation and/or development.

Studies suggest that the persistence of treponemes in lesions of DD act as a source of recurrent infections, not only in the same animal but in naïve populations.Citation52 Such persistence is a hallmark of disease associated with other treponemes including those involved with human periodontal disease and syphilis; indeed persistence is a hallmark of infection by many spirochetes. Thus, appropriate studies are required to supplement our current understanding and specifically address the causes of lesion initiation and the use of topical as well as systemic treatments to limit disease recurrence. These are not trivial tasks and ultimately require the use of appropriate animal models of infection.

BDD has been experimentally reproduced;Citation76 DD is a polybacterial disease process, and no single etiological agent can reproduce the disease in experimentally infected bovines. Attempts to induce BDD lesions with cultures of T. phagedenis have been unsuccessful (Alt, unpublished data).Citation77 However, when Holstein heifers of 14–16 months of age were treated such that their rear legs were subjected to prolonged moisture (maceration) and reduced access to air (closure), the inoculation of BDD lesion material resulted in the diagnosis of BDD histopathologically by 17 days postinfection in four of six legs.Citation76 Use of a clonal isolate of a T. vincentii-like organism caused BDD in only one of four legs. These results highlight the need for the use of lesion material (and thus polybacterial material) as well as a suitably predisposed damaged foot surface to facilitate disease development. In modeling disease, while the native host is always best, near substitutes may be more practical. Mature bovines present considerable logistics for evaluation of hoofs on a daily basis. Other small ruminants (sheep or goats), having already demonstrated natural susceptibility to disease, may be a feasible alternative.

In contrast, another recent study failed to observe transmission from clinically affected cows cohoused with eight healthy heifers over a period of 8 weeks despite employing several housing and environmental modifications in an attempt to enhance transmission.Citation33 These studies must be viewed in light of other data collected indicating the contribution of additional predisposing factors required for the development and expression of disease. Predisposing factors are complex and varied; they range from negative energy balance to poor hoof conformation.

DD is a polytreponemal disease. A relatively few number of DD treponemes are amenable to culture and thus available for a more comprehensive analysis at the molecular level. For most DD isolates, little work has been done on virulence attributes. It is clear that these treponemes comprise a group that have different physical appearance (in length, thickness, and number of flagella),Citation10,Citation16,Citation26,Citation78 different nutritional requirements (eg, use of fetal calf serum in medium compared to rabbit serum),Citation79 host interactions,Citation80,Citation81 as well as the expression of different protein profiles.Citation40,Citation50 BDD treponeme isolates can be differentiated from bovine gastrointestinal treponeme isolates by the presence of tlyC,Citation82 a hemolysin and putative virulence factor, but other virulence factors that contribute to pathogenesis are not known. These questions require the continued development of culture methods, genomic sequencing, and proteomics profiles of DD isolates. Such studies are confounded by the need to consider appropriate synergies with other nontreponemal bacterial isolates from DD lesions. Whilst similarities exist with the dental pathogens, drawing assumptions across isolates from such widely differing ecological niches may diminish unique attributes of the DD treponemes.

Concluding remarks

Globally recognized, lameness in animals is a major issue both from the standpoint of economic losses due to decreased production but also represents a serious animal welfare issue. The paradox of modern animal agriculture is that many of the husbandry practices intended to enhance performance also enhance predisposition for damaged hooves and infectious hoof disease transmission. Although the ideal situation is always complete elimination of a pathogen or disease, DD may need to be managed through the concept of endemic stability. In endemic stability, it is a balance of infection and disease, as individuals are exposed, immunity is developed, and for much of the population, disease is minimized.Citation83 Individuals exhibiting disease are treated promptly and the environment is managed for low exposure levels. Since endemic stability requires that as the prevalence of infection increases the prevalence of disease decreases, pathogens that lend themselves to management through endemic stability tend to generate immune responses that are partial or that wane, resulting in repeated bouts of infection. Better knowledge about initiating events of DD and the role of the various bacterial pathogens in the infection would make management more precise. However, whilst this type of disease management is often the recourse for domestic livestock, it is detrimental to wildlife populations as there is little or no intervention for those individuals developing disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jim Fosse, Gearóid Sayers and Karen Mansfield for images of bovine, ovine, and cervine lesions respectively. We also thank the three anonymous reviewers for constructive critique. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ReadDHWalkerRLPapillomatous digital dermatitis (footwarts) in California dairy cattle: clinical and gross pathologic findingsJ Vet Diagn Invest199810167769526863

- Knappe-PoindeckerMGilhuusMJensenTKKlitgaardKLarssenRBFjeldaasTInterdigital dermatitis, heel horn erosion, and digital dermatitis in 14 Norwegian dairy herdsJ Dairy Sci201396127617762924140335

- DuncanJSAngellJWCarterSDEvansNJSullivanLEGrove-WhiteDHContagious ovine digital dermatitis: an emerging diseaseVet J2014201326526824973004

- CleggSRMansfieldKGNewbrookKIsolation of digital dermatitis treponemes from hoof lesions in wild North American elk (Cervus elaphus) in Washington State, USAJ Clin Microbiol2015531889425355757

- HanSMansfieldKGSevere hoof disease in free-ranging Roosevelt elk (Cervus elaphus roosevelti) in southwestern Washington, USAJ Wildlife Dis2014502259270

- CheliRMortellaroCDigital dermatitis in cattleProc 8th Int Meet Dis Cattle, Milan, Italy19748208213

- RebhunWCPayneRMKingJMWolfeMBeggSNInterdigital papillomatosis in dairy cattleJ Am Vet Med Assoc198017754374407440341

- BloweyRWDoneSHCooleyWObservations on the pathogenesis of digital dermatitis in cattleVet Rec199413551151178737483

- LosingerWCEconomic impacts of reduced milk production associated with papillomatous digital dermatitis in dairy cows in the USAJ Dairy Res200673224425616569275

- DopferDKoopmansAMeijerFAHistological and bacteriological evaluation of digital dermatitis in cattle, with special reference to spirochaetes and Campylobacter faecalisVet Rec1997140246206239228692

- KrullACShearerJKGordenPJCooperVLPhillipsGJPlummerPJDeep sequencing analysis reveals temporal microbiota changes associated with development of bovine digital dermatitisInfect Immun20148283359337324866801

- LavenRAHuntHEvaluation of copper sulphate, formalin and peracetic acid in footbaths for the treatment of digital dermatitis in cattleVet Rec2002151514414612199433

- ManskeTHultgrenJBergstenCTopical treatment of digital dermatitis associated with severe heel-horn erosion in a Swedish dairy herdPrevent Vet Med2002533215231

- HolzhauerMBartelsCJDopferDvan SchaikGClinical course of digital dermatitis lesions in an endemically infected herd without preventive herd strategiesVet J2008177222223017618149

- BerrySLReadDHFamulaTRMonginiADopferDLong-term observations on the dynamics of bovine digital dermatitis lesions on a California dairy after topical treatment with lincomycin HClVet J2012193365465822892182

- WalkerRLReadDHLoretzKJNordhausenRWSpirochetes isolated from dairy cattle with papillomatous digital dermatitis and interdigital dermatitisVet Microbiol1995473–43433558748549

- NielsenBHThomsenPTGreenLEKalerJA study of the dynamics of digital dermatitis in 742 lactating dairy cowsPrevent Vet Med20121041–24452

- NielsenBHThomsenPTSorensenJTA study of duration of digital dermatitis lesions after treatment in a Danish dairy herdActa Vet Scand2009512719570191

- BloweyRWDoneSHFailure to demonstrate histological changes of digital or interdigital dermatitis in biopsies of slurry heelVet Rec1995137153793818578651

- SullivanLECarterSDBloweyRDuncanJSGrove-WhiteDEvansNJDigital dermatitis in beef cattleVet Rec201317323582

- BrownCCKilgoPDJacobsenKLPrevalence of papillomatous digital dermatitis among culled adult cattle in the southeastern United StatesAm J Vet Res200061892893010951985

- CollighanRJWoodwardMJSpirochaetes and other bacterial species associated with bovine digital dermatitisFEMS Microbiol Lett1997156137419368358

- DaviesIHNaylorRDMartinPKSevere ovine foot diseaseVet Rec19991452264610619613

- BassettHFMonaghanMLLenhanPDohertyMLCarterMEBovine digital dermatitisVet Rec19901267164165

- KlitgaardKFoix BretoABoyeMJensenTKTargeting the treponemal microbiome of digital dermatitis infections by high-resolution phylogenetic analyses and comparison with fluorescent in situ hybridizationJ Clin Microbiol20135172212221923658264

- ChoiBKNattermannHGrundSHaiderWGobelUBSpirochetes from digital dermatitis lesions in cattle are closely related to treponemes associated with human periodontitisInt J Syst Bacteriol19974711751819019153

- RasmussenMCapionNKlitgaardKBovine digital dermatitis: possible pathogenic consortium consisting of Dichelobacter nodosus and multiple Treponema speciesVet Microbiol20121601–215116122698300

- CruzCEPescadorCANakajimaYDriemeierDImmunopathological investigations on bovine digital epidermitisVet Rec20051572683484016377788

- EvansNJBrownJMDemirkanIAssociation of unique, isolated treponemes with bovine digital dermatitis lesionsJ Clin Microbiol200947368969619144804

- Wilson-WelderJHElliottMKZuernerRLBaylesDOAltDPStantonTBBiochemical and molecular characterization of Treponema phagedenis-like spirochetes isolated from a bovine digital dermatitis lesionBMC Microbiol20131328024304812

- EvansNJBrownJMDemirkanITreponema pedis sp. nov., a spirochaete isolated from bovine digital dermatitis lesionsInt J Syst Evol Microbiol200959Pt 598799119406779

- CollighanRJNaylorRDMartinPKCooleyBABullerNWoodwardMJA spirochete isolated from a case of severe virulent ovine foot disease is closely related to a Treponeme isolated from human periodontitis and bovine digital dermatitisVet Microbiol200074324925710808093

- CapionNBoyeMEkstromCTJensenTKInfection dynamics of digital dermatitis in first-lactation Holstein cows in an infected herdJ Dairy Sci201295116457646422939796

- MoeKKYanoTMisumiKDetection of antibodies against Fusobacterium necrophorum and Porphyromonas levii-like species in dairy cattle with papillomatous digital dermatitisMicrobiol Immunol201054633834620536732

- Knappe-PoindeckerMGilhuusMJensenTKVatnSJorgensenHJFjeldaasTCross-infection of virulent Dichelobacter nodosus between sheep and co-grazing cattleVet Microbiol20141703–437538224698131

- DuncanJSGrove-WhiteDMoksEImpact of footrot vaccination and antibiotic therapy on footrot and contagious ovine digital dermatitisVet Rec20121701846222266683

- DemirkanIWalkerRLMurrayRDBloweyRWCarterSDSerological evidence of spirochaetal infections associated with digital dermatitis in dairy cattleVet J19991571697710030131

- ElliottMKAltDPBovine immune response to papillomatous digital dermatitis (PDD)-associated spirochetes is skewed in isolate reactivity and subclass elicitationVet Immunol Immunopathol20091303–425626119297029

- MoeKKYanoTMisumiKAnalysis of the IgG immune response to Treponema phagedenis-like spirochetes in individual dairy cattle with papillomatous digital dermatitisClin Vaccine Immunol201017337638320107009

- TrottDJMoellerMRZuernerRLCharacterization of Treponema phagedenis-like spirochetes isolated from papillomatous digital dermatitis lesions in dairy cattleJ Clin Microbiol20034162522252912791876

- WalkerRLReadDHLoretzKJHirdDWBerrySLHumoral response of dairy cattle to spirochetes isolated from papillomatous digital dermatitis lesionsAm J Vet Res19975877447489215451

- GomezAAnklamKSCookNBImmune response against Treponema spp. and ELISA detection of digital dermatitisJ Dairy Sci20149784864487524931522

- MurrayRDDownhamDYDemirkanICarterSDSome relationships between spirochaete infections and digital dermatitis in four UK dairy herdsRes Vet Sci200273322323012443678

- VinkWDJonesGJohnsonWODiagnostic assessment without cut-offs: application of serology for the modelling of bovine digital dermatitis infectionPrevent Vet Med2009923235248

- MoterALeistGRudolphRFluorescence in situ hybridization shows spatial distribution of as yet uncultured treponemes in biopsies from digital dermatitis lesionsMicrobiology1998144Pt 9245924679782493

- EvansNJTimofteDIsherwoodDRHost and environmental reservoirs of infection for bovine digital dermatitis treponemesVet Microbiol20121561–210210922019292

- ShibaharaTOhyaTIshiiRConcurrent spirochaetal infections of the feet and colon of cattle in JapanAust Vete J2002808497502

- ZuernerRLHeidariMElliottMKAltDPNeillJDPapillomatous digital dermatitis spirochetes suppress the bovine macrophage innate immune responseVet Microbiol20071253–425626417628359

- ScholeyREvansNBloweyRIdentifying host pathogenic pathways in bovine digital dermatitis by RNA-Seq analysisVet J2013197369970623570776

- EvansNJBrownJMScholeyRDifferential inflammatory responses of bovine foot skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes to digital dermatitis treponemesVet Immunol Immunopathol20141611–2122025022220

- MeeJFGeraghtyTO’NeillRMoreSJBioexclusion of diseases from dairy and beef farms: risks of introducing infectious agents and risk reduction strategiesVet J2012194214315023103219

- RelunALehebelABrugginkMBareilleNGuatteoREstimation of the relative impact of treatment and herd management practices on prevention of digital dermatitis in French dairy herdsPrevent Vet Med20131103–4558562

- SullivanLEBloweyRWCarterSDPresence of digital dermatitis treponemes on cattle and sheep hoof trimming equipmentVet Rec2014175820124821857

- WhayHBarkerZLeachKMainDPromoting farmer engagement and activity in the control of dairy cattle lamenessVet J2012193361762122892183

- WardWWhy is lameness in dairy cows so intractable?Vet J2009180213914018929496

- MainDLeachKBarkerZEvaluating an intervention to reduce lameness in dairy cattleJ Dairy Sci20129562946295422612932

- BellNBellMKnowlesTWhayHMainDWebsterAThe development, implementation and testing of a lameness control programme based on HACCP principles and designed for heifers on dairy farmsVet J2009180217818818694651

- KlitgaardKNielsenMWIngerslevHCBoyeMJensenTKDiscovery of bovine digital dermatitis-associated Treponema spp. in the dairy herd environment by a targeted deep-sequencing approachAppl Environ Microbiol201480144427443224814794

- DopferDHolzhauerMBovenMVThe dynamics of digital dermatitis in populations of dairy cattle: Model-based estimates of transition rates and implications for controlVet J2012193364865322878094

- BerrySLReadDHWalkerRLFamulaTRClinical, histologic, and bacteriologic findings in dairy cows with digital dermatitis (footwarts) one month after topical treatment with lincomycin hydrochloride or oxytetracycline hydrochlorideJ Am Vet Med Assoc2010237555556020807134

- MumbaTDopferDKruitwagenCDreherMGaastraWvan der ZeijstBADetection of spirochetes by polymerase chain reaction and its relation to the course of digital dermatitis after local antibiotic treatment in dairy cattleZentralbl Veterinarmed B199946211712610216454

- van AmstelSRvan VuurenSTuttCLDigital dermatitis: report of an outbreakJ S Afr Vet Assoc19956631771818596191

- HolzhauerMHardenbergCBartelsCJFrankenaKHerd- and cow-level prevalence of digital dermatitis in the Netherlands and associated risk factorsJ Dairy Sci200689258058816428627

- SomersJGFrankenaKNoordhuizen-StassenENMetzJHRisk factors for digital dermatitis in dairy cows kept in cubicle houses in The NetherlandsPrevent Vet Med2005711–21121

- ScholeyROllierWBloweyRMurrayRCarterSDetermining host genetic susceptibility or resistance to bovine digital dermatitis in cattleAdv Animal Biosci20101012

- OnyiroOMAndrewsLJBrotherstoneSGenetic parameters for digital dermatitis and correlations with locomotion, production, fertility traits, and longevity in Holstein-Friesian dairy cowsJ Dairy Sci200891104037404618832230

- EvansNJBloweyRWTimofteDAssociation between bovine digital dermatitis treponemes and a range of ‘non-healing’ bovine hoof disordersVet Rec2011168821421493554

- MooreLJWoodwardMJGrogono-ThomasRThe occurrence of treponemes in contagious ovine digital dermatitis and the characterisation of associated Dichelobacter nodosusVet Microbiol20051113–419920916280206

- KarlssonFKlitgaardKJensenTKIdentification of Treponema pedis as the predominant Treponema species in porcine skin ulcers by fluorescence in situ hybridization and high-throughput sequencingVet Microbiol2014171112213124725449

- SvartströmOKarlssonFFellströmCPringleMCharacterization of Treponema spp. isolates from pigs with ear necrosis and shoulder ulcersVet Microbiol2013166361762323948134

- PringleMFellströmCTreponema pedis isolated from a sow shoulder ulcerVet Microbiol2010142346146320004066

- MoeKKYanoTKuwanoASasakiSMisawaNDetection of treponemes in canker lesions of horses by 16S rRNA clonal sequencing analysisJ Vet Med Sci201072223523919942809

- NagamineCMCastroFBuchananBSchumacherJCraigLEProliferative pododermatitis (canker) with intralesional spirochetes in three horsesJ Vet Diagn Invest200517326927115945386

- Rashmir-RavenAMBlackSSRickardLGAkinMPapillomatous pastern dermatitis with spirochetes and Pelodera strongyloides in a Tennessee Walking HorseJ Vet Diagn Invest200012328729110826850

- SykoraSBrandtSOccurrence of Treponema DNA in equine hoof canker and normal hoof tissueEquine Vet J Epub8132014

- GomezACookNBBernardoniNDAn experimental infection model to induce digital dermatitis infection in cattleJ Dairy Sci20129541821183022459830

- PringleMBergstenCFernstromLLHookHJohanssonKEIsolation and characterization of Treponema phagedenis-like spirochetes from digital dermatitis lesions in Swedish dairy cattleActa Vet Scand2008504018937826

- DopferDAnklamKMikheilDLadellPGrowth curves and morphology of three Treponema subtypes isolated from digital dermatitis in cattleVet J2012193368569322901455

- EvansNJBrownJMDemirkanIThree unique groups of spirochetes isolated from digital dermatitis lesions in UK cattleVet Microbiol20081301–214115018243592

- EdwardsAMDymockDWoodwardMJJenkinsonHFGenetic relatedness and phenotypic characteristics of Treponema associated with human periodontal tissues and ruminant foot diseaseMicrobiology2003149Pt 51083109312724370

- EdwardsAMDymockDJenkinsonHFFrom tooth to hoof: treponemes in tissue-destructive diseasesJ Appl Microbiol200394576778012694441

- EvansNJBrownJMMurrayRDCharacterization of novel bovine gastrointestinal tract Treponema isolates and comparison with bovine digital dermatitis treponemesAppl Environ Microbiol201177113814721057019

- GreenLEGeorgeTAssessment of current knowledge of footrot in sheep with particular reference to Dichelobacter nodosus and implications for elimination or control strategies for sheep in Great BritainVet J2008175217318017418598

- SantosTMPereiraRVCaixetaLSGuardCLBicalhoRCMicrobial diversity in bovine papillomatous digital dermatitis in Holstein dairy cows from upstate New YorkFEMS Microbiol Ecol201279251852922093037

- SayersGMarquesPXEvansNJIdentification of spirochetes associated with contagious ovine digital dermatitisJ Clin Microbiol20094741199120119204100

- KoniarovaIOrsagALedeckýVThe role anaerobes in dermatitis digitalis et interdigitalis in cattleVet Med19923810589596 Slovak

- SchlaferSNordhoffMWyssCInvolvement of Guggenheimella bovis in digital dermatitis lesions of dairy cowsVet Microbiol20081281–211812518024006

- WyssCMoterAChoiBKTreponema putidum sp. nov., a medium-sized proteolytic spirochaete isolated from lesions of human periodontitis and acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitisInt J Syst Evol Microbiol200454Pt 41117112215280279

- SchroederCMParlorKWMarshTLAmesNKGoemanAKWalkerRDCharacterization of the predominant anaerobic bacterium recovered from digital dermatitis lesions in three Michigan dairy cowsAnaerobe20039315115516887703

- OhyaTYamaguchiHNiiYItoHIsolation of Campylobacter sputorum from lesions of papillomatous digital dermatitis in dairy cattleVet Rec19991451131631810515621