?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the impact of alcohol use, which is widespread in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)+ individuals, on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)-associated immune and cognitive improvements and the relationship between those two responses.

Methods:

In a case-control longitudinal study, thymic volume, cognition, and immune responses were evaluated at baseline and after 6 months therapy in HIV+ and HIV- controls. Cognitive performance was evaluated using the HIV Dementia Score (HDS) and the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT).

Results:

Prior to HAART, thymic volume varied considerably from 2.7 to 29.3 cm3 (11 ± 7.2 cm3). Thymic volume at baseline showed a significantly inverse correlation with the patient’s number of years of drinking (r2 = 0.207; p < 0.01), as well as HDS and the CVLT scores in both HIV-infected (r2 = 0.37, p = 0.03) and noninfected (r2 = 0.8, p < 0.01). HIV-infected individuals with a small thymic volume scored in the demented range, as compared with those with a larger thymus (7 ± 2.7 vs. 12 ± 2.3, p = 0.005). After HAART, light/moderate drinkers exhibited thymus size twice that of heavy drinkers (14.8 ± 10.4 vs. 6.9 ± 3.3 cm3).

Conclusions:

HAART-associated increases of thymus volume appear to be negatively affected by alcohol consumption and significantly related to their cognitive status. This result could have important clinical implications.

Introduction

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic is a major international public health problem (CitationWHO 2005). Although the primary target of this virus is the immune system, neurological abnormalities are common in patients infected with HIV (CitationBean 2001). The immune system and central nervous system (CNS), once considered completely independent, have been demonstrated to be closely linked (CitationDalakas et al 1986; CitationFabris et al 1988; CitationSpangelo 1995; CitationAntoniou et al 1997; CitationTurrini et al 1998; CitationSavino and Dardenne 2000; CitationNishiyama 2001; CitationMorale et al 2003; CitationCavalloti et al 2005; CitationFleming et al 2005). Bidirectional communication between the brain and the thymus has been described in numerous studies, in association with cytokines, hormones, growth factors, and neurotransmitters (CitationFabris et al 1988; CitationAntoniou et al 1997; CitationMorale et al 2003; CitationCavalloti et al 2005). These factors enable the thymus, which plays a critical role during highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) reconstitution, to act at sites distant from it, and it influences the ontogenesis and function of both the immune system and CNS. Unfortunately, its role has been overlooked in terms of HIV disease. Therefore, the present study explored the role of alcohol use in cognitive impairment and recuperation from HAART through its impact on the thymus.

Methods

Sampling

Participants aged 18 to 55 years, who had been diagnosed with HIV and had been receiving a new antiretroviral regimen for less than 10 weeks, were eligible to be enrolled in the Miami Alcohol Research Care for HIV (MARCH) study. Briefly, MARCH is a longitudinal observational study to evaluate the impact of alcohol use on health status of HIV-infected individuals receiving HAART. Participants were recruited from the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and Jackson Memorial clinics, where these individuals are followed at regular intervals. Antiretroviral eligibility criteria were as follows: HIV-infected subjects could be either 1) naïve or 2) had prior exposure to antiretroviral therapy, but they must have discontinued HAART for at least 6 weeks prior to starting this new regimen. The HIV cohort was matched by stratifying gender, age, and race with an HIV seronegative (as per laboratory testing during the previous six months) community control, consisting of friends and relatives of enrolled participants for comparing study outcomes.

Participants were divided into hazardous (Group 1) and nonhazardous drinkers (Group 2), according to National Institute of Alcohol and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA) and American Association guidelines (CitationFleming 2005). Alcohol consumption assessments included widely-used standardized and validated brief screening questionnaires: Physician’s Guide (NIAAA) (CitationFleming 2005), Cut, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye opener (CAGE), Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT), and Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS). Men who reported >14 and women >7 or more drinks/week were enrolled in Group 1, while those who reported fewer drinks were included in Group 2. Those who provided written informed consent and medical release were enrolled. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Miami approved the study.

Using standardized questionnaires, the following data were collected: sociodemographic information, drugs, alcohol use habits, and past and current medical history. HIV positives were questioned with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria to establish HIV disease status. Medical prescriptions were documented and a standardized antiretroviral adherence questionnaire administered. After visit procedures were completed, a medical chart and pharmacy records were abstracted and patient information was validated.

Immune assessments

Blood samples were collected from all participants and processed within 6 hours. Isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells were prepared for four-color direct immunofluorecence procedures (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Flow cytometry quantified the percentage and absolute numbers of T lymphocyte sub populations CD3+/CD4+ and CD3+/CD8. In addition, HIV viral burden was quantified using the Amplicor HIV monitor test (Roche Diagnostic System).

Thymus

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging was selected over computed tomography (CT) because MR provides superior soft tissue contrast, and avoids the use of ionizing radiation and contrast administration (CitationDe Geer et al 1986; CitationWatzl et al 1993). The MR was obtained only in a sub-sample of patients that, were adherent to their prescribed medication after the first month. The MR was performed using a thoracic surface coil and electrocardiographic gating, and consisted of the following sequences: 1) Sagittal and coronal pilots; 2) T1-weighted axial, slice thickness 6 mm, interslice gap 1 mm, 4 averages; and 3) T2-weighted axial fat-suppressed, slice thickness 6 mm, interslice gap 1 mm, 4 averages. Thymic volume can be estimated from the sum of the areas of manually drawn regions-of-interest from each image on which glandular thymic tissue appears. However, the adult thymus is generally fatty involuted, and calculations of true glandular volume may be inaccurate if fatty elements are not excluded. Therefore, we instead performed a quantitative thymic volume calculation by measuring total mediastinal area, mean mediastinal signal intensity (SI [mediastinum]), fat signal intensity (SI [fat]), and muscle signal intensity (SI [muscle]) on each T1 weighted slice. We assumed that pure glandular (thymic) tissue would have a signal intensity similar to that of muscle, whereas a completely fatty involuted thymus would have a signal intensity of fat. For each slice from the left brachiocephalic vein superiorly to the main pulmonary artery inferiorly, we then calculated thymic area using the following formula:

Quantitative thymic area

The sum of thymic areas was then multiplied by the slice thickness plus interslice gap (7 mm) to obtain total thymic volume.

Cognition

The HIV Dementia Scale (HDS) was used as a valid screening tool with 10 as a cutoff point. The HDS had a sensitivity of 80%, specificity 91%, and positive predictive value 78% for identifying HIV dementia (CitationPower et al 1995). The HDS was shown as superior to other widely used rapid screening tests (Mini-Mental State Examination). In addition, it has been previously used to monitor therapeutic effects on the CNS (CitationDougherty et al 2002). The HDS is comprised of four tasks that evaluate the domains of memory, attention, psychomotor speed, and construction.

The California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) is a multidimensional measure of verbal learning and memory, which includes two word lists, each of which contains 16 shopping items (CitationDelis et al 1987). Items are distributed according to a Monday list and a Tuesday distracter list, with scores representing the number of objects that an individual can recall. Participants are asked to recall the Monday list spontaneously, following semantic cues and after a 20-minute delay. Finally, participants are given a “yes/no” recognition test in which they are presented with the 16 target words embedded within a list of 28 nontarget words. Scores are based on the number of words provided by the participant on the various trials and on the number of times they correctly identify a word to be a member or not of the first list (CitationDelis et al 1987).

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed using SAS version 8 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and SPSS version 11 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and p values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Following descriptive statistical analyses, mean variables were compared using Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) procedures. Correlations among the main variables of interest were examined with Pearson’s coefficients.

Logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the effects of alcohol, HAART, and other potential risk factors on cognition. Univariate analyses were used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

To identify the pattern of change in cognitive status over time and under the effect of HAART (no change, decrease, or increase), differences in average scores between baseline and second visit evaluation were assessed using t-tests for paired samples and analyzed by thymus size and alcohol groups.

Finally, linear regression analyses were performed for each comparison. Although no significant differences were observed between groups for education level or CDC status, both variables were controlled for in the final analyses.

Results

Study population characteristics

This longitudinal study assessed a multiethnic sample of 162 HIV-infected subjects, including 89 hazardous drinkers and 73 nonhazardous drinkers. The 35 HIV seronegative participants included 20 hazardous and 15 nonhazardous drinkers. Participants ranged in age from 24 to 54 years (mean 40 ± 7 years). More than half (66%) of the participants were male and 34% were female. Years of education varied across the sample from 1–16 years (mean 11.4 ± 3 years) and 25% had more than 12 years of education.

Approximately one-third of the participants acknowledged current drug abuse, particularly crack/cocaine and marijuana.

The sample reported an average of 20 ± 2 drinks/week, along with a well-documented history of continuous alcohol consumption averaging 8 ± 7 drinks per day for more than a month prior to sampling. Despite receiving HAART, the HIV-infected group reported average weekly alcohol consumption similar to the seronegative individuals (22 ± 2.5 vs. 25 ± 4.3 drinks). No significant difference in any of the above mentioned characteristics was observed between HIV seropositives and seronegatives.

The mean CD4 cell count of the total group was 255.3 ± 242.8. On average, the study sample had a viral load of 227,899 ± 140,834 copies. Only half of the study participants reported full adherence to their medication and received a MR evaluation ().

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of study population by alcohol consumption

Cognition

At baseline, 60% of HIV positives had total scores below 9 of 16 possible points, indicating dementia. No significant correlations were found between the HDS scores and age, education, viral load, CD4, or drug use.

A significant correlation was observed between total drinks per week and mental status, as indicated by baseline total HDS (r2 = 0.22, p = 0.003). The seronegative nonhazardous drinkers exhibited the highest HDS scores (12.5 ± 3.8), followed by HIV-infected nonhazardous drinkers (10.4 ± 4), HIV seronegative hazardous drinkers (8.6 ± 5 total score), and those with dual co-morbidity (8.4 ± 3.7). No significant effects of gender, age, or education were observed in HDS total scores.

The correlation between alcohol drinks/week and HDS score remained significant after six months of HAART (r = 0.16, p = 0.02). Significantly low mean HDS total scores were noted in hazardous alcohol users, compared with nonhazardous alcohol users (df = 162, F = 1.94; 9.2 ± 3.5 vs. 10.5 ± 3.8, p = 0.04). Moreover, all HIV-infected heavy alcohol users scored <8 on the HDS. Univariate analyses indicate that HIV-infected hazardous alcohol users were more likely to have dementia compared with seronegative nondrinkers (OR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1–2.38, p = 0.05). After HAART, paired t-test analyses indicated no changes in total HDS scores in either hazardous alcohol users or nonhazardous drinkers.

Negative correlations were evident between drinks/week and both Monday (r2 = −0.21, p = 0.009) and Tuesday recalls (r2 = −0.15, p = 0.04). No significant correlations were found between the CVLT and age, gender, level of education, or drug use. Low mean Monday scores on the CVLT were evident in the seronegative nonhazardous drinkers, as compared with the seronegative hazardous drinkers (df = 35, F = 1.18; 11.4 ± 2.9 vs. 10 ± 3.7, p = 0.04), and were also lower for the Tuesday list (df = 35, 5 ± 2 vs. 7.6 ± 2.6, p = 0.003). The groups also tended to differ in the long delay free recall test (df = 35, 11.6 ± 3 vs 9.3 ± 4 words, p = 0.07). Low mean scores on the CVLT were evident in HIV-infected hazardous alcohol drinkers. Recall for both short and long delays was poorer in HIV-infected hazardous alcohol drinkers (df = 162, 8 ± 3 and 9 ± 4 items, respectively) than in HIV-infected nonhazardous alcohol drinkers (df = 162, 9.5 ± 3.7 items, p = 0.05; 10 ± 4 words, p = 0.06; See .). Delay recognition scores were also significantly worse in HIV-infected hazardous alcohol drinkers than in HIV nonhazardous drinkers (df = 162, F = 2.49; 10.5 ± 3.7 words vs. 12.8 ± 3.2 words, p = 0.03).

Table 2 Cognitive and immune baseline characteristics

Statistically significant improvement in short memory tasks (change = 1–2 words) was evident after six months of HAART in both hazardous alcohol drinkers (p = 0.001) and nonhazardous alcohol drinkers (p = 0.001). The previous observed difference in the HIV positive groups persisted at the six-month evaluation. Hazardous alcohol drinkers were twice as likely as nonhazardous alcohol drinkers to forget more words (remember less than 10/15 words, 95% CI: 1–6.6; p = 0.04). Long delay free recall remained significantly lower after HAART treatment in hazardous alcohol drinkers, than in HIV-infected nonhazardous alcohol drinkers (df = 162, F = 1.94; 8.8 ± 3 words vs. 10.4 ± 4; p = 0.03). No significant changes between baseline and six-month evaluations were evident in any of the study parameters in the noninfected group.

Baseline cognitive performance according to immune parameters

Thymus size was significantly correlated with total HDS score (r2 = 0.5, p = 0.05) at baseline. Patients were separated into those with thymus volumes above or below 13 cm3, which corresponds to the mean volume of the HIV negative control population. Participants with a small thymus scored in the demented range (7 ± 2.7) compared with those with a larger thymus (df = 87, F = 2.6; 12 ± 2.3, p = 0.005). Importantly, a smaller thymus size was characteristic of HIV-infected hazardous alcohol drinkers and none and/or no significant improvement in CD4 cell counts after 6 months of treatment ().

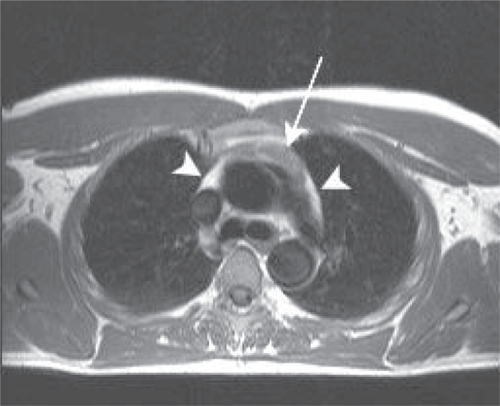

Figure 1 Axial T1 weighted image of the thymus of an antiretroviral treated nonhazardous drinker. The thymus (arrow) is of intermediate signal intensity with small amounts of higher intensity fat (arrowheads) around it.

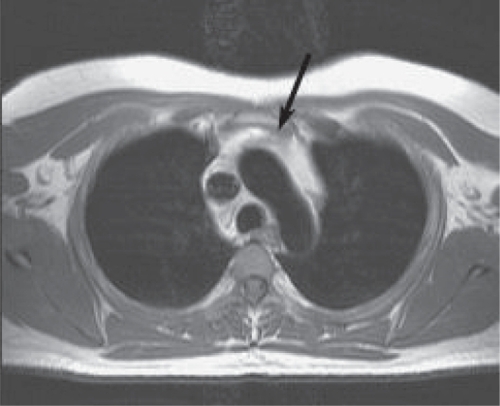

Figure 2 Axial T1 weighted image of the thymus of an antiretroviral treated hazardous drinker. The mediastinum largely consists of high intensity fat, with a small thymus (black arrow).

Thymus size was also correlated with the CVLT scores in both HIV-infected (r2 = 0.37, p = 0.03) and noninfected participants (r2 = 0.8, p = 0.01). Correlations between CVLT scores and thymus size were generally highest among HIV-infected individuals. A positive, significant correlation was also noted between thymus size and the Monday recall list (r2 = 0.4, p = 0.05). Univariate analyses indicated that patients with a thymus size >13 cm3 were 5 times more likely to recall more than 8 words in the Monday list (95% CI: 1.2–16.0, p = 0.02).

HIV-infected participants with more than 200 CD4 cell counts exhibited similar total HDS (10.1 ± 3.9 vs. 9.4 ± 3.3) and CVLT (11.7 ± 3.3 vs. 10.9 ± 2.6; p > 0.05) scores, as compared with those with less than 200 CD4 cell counts.

After 6 months of HAART

After 6 months of HAART, thymus volumes increased an average of 25% (5 ± 3 cm3). On average, nonhazardous alcohol drinkers significantly improved their CD4 by 20 cell counts (p = 0.04), which contrasted with only a 3 cell improvement among the hazardous alcohol drinkers. Accordingly, those with a large thymus improved on average by 25 cell counts, while those with a small thymus lost 34 CD4+ cell counts despite treatment. The sample sizes were insufficient to allow analyses by regimen type or by CNS penetration.

After HAART, a slight increase in mean HDS scores was observed in all groups, except for the hazardous drinkers with a small thymus. Nonhazardous drinkers with a larger thymus after HAART exhibited the highest HDS scores (13.8 ± 1.3), followed by nonhazardous drinkers with a small thymus (11.6 ± 2.4), hazardous drinkers with a small thymus (8.9 ± 5 total score), and those with dual co-morbidity (7.4 ± 2.7). Longitudinal analyses indicated that participants with a smaller thymus were twice as likely to score in the demented range as those with a larger thymus (RR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1–2.3, p = 0.05).

Statistically significant improvement in short memory tasks (change = 1–2 words) was also evident in both hazardous alcohol drinkers (p = 0.001) and nonhazardous alcohol drinkers (p = 0.001). The correlation between thymus size and short-delay recall was even stronger (r2 = 0.6, p = 0.008) after HAART. Thymus size also correlated with long delay free recall (r2 = 0.7, p = 0.003). Additional analyses indicated significantly poorer recall scores in HIV seropositives with a smaller thymus (short delay: 8.9 ± 2.4 words and long delay: 9.1 ± 2.6 words), compared with those with a normal size thymus (13.6 ± 2.8 items, p = 0.01; 13 ± 3.4 words, p =0.05; See ). After HAART, HIV-infected subjects with a small thymus were still twice as likely as HIV positives with >13 cm of thymus to remember fewer than 8 items in the Monday list (95% CI: 1.1–4.4, p = 0.04). They were also less likely to remember more than 5 items in the Tuesday list (RR = 6, p = 0.03).

Table 3 Cognitive and immune measurements after 6 months of HAART according to thymus size

Patients that increased their thymus size after HAART had significantly improved recall (Monday list change 2 ± 0.8, p = 0.03) and long delayed free recall (1.9 ± 0.6, p = 0.01). In contrast, no significant improvement in recall was shown for those whose thymus failed to increase in size (Monday 0.2 ± 0.1 and long delayed 0.4 ± 0.1).

In the final analyses, age, CDC stage, alcohol consumption, education, and thymus size were included as dichotomous variables in the final regression model with HDS as the dependent variable. As illustrated in , hazardous alcohol consumption (RR = 9; 95% CI: 1.0–98, p = 0.04) and small thymus (RR = 7.5; 95% CI: 1.5–38, p = 0.01) were the only variables associated with HIV dementia after adjusting for potential confounders.

Table 4 Odds ratios for dementia according to alcohol intake

Discussion

Until recently, it was thought that a close interaction between the thymus and the CNS only occurred during development. However, we have made a remarkable medical discovery in humans. The thymus is closely related to cognitive status in HIV-infected and noninfected adults. Furthermore, additional analyses indicated that cognitive task restoration following HAART administration is associated with thymus regeneration and impacted by alcohol consumption.

Thymus size effects were evident at baseline in both HDS and CVLT tests and observed in both HIV-infected and non-infected participants. Notably, correlations were generally highest among HIV-infected individuals and related to the deleterious effects of alcohol and HIV in these individuals. These findings confirm and extend previous animal studies that have found a significant relationship between cognitive and CNS structural changes and thymus (CitationSong and Bao 1991; Saito et al 1994; CitationZhang et al 1994; CitationWang and Spitzer 1997). Athymic mice and thymectomized rats have been reported to exhibit memory impairment in spatial and conditioned memory. Alterations in learning performance have been consistently observed at 3, 5, and 10 months post-thymectomy, suggesting that the thymus significantly influenced learning and memory ability (CitationSong and Bao 1991; Saito et al 1994; CitationZhang et al 1994; CitationWang and Spitzer 1997; CitationNishiyama 2001). The operation also results in an underdeveloped brain with a thin cortex and changes in learning performance. However, if the thymus is re-implanted, the frontal area becomes as thick as normal (CitationSong and Bao 1991; Saito et al 1994; CitationZhang et al 1994; CitationWang and Spitzer 1997). These findings are of particular relevance to our study, as neuropsychological disturbances associated with HIV-1 infection are consistent with dysfunction of frontal-subcortical circuitry (CitationMeyerhoff 2001). Cytokines, prolactin, and thymosins are some of many candidates for the role of messengers mediating thymus induction of cognitive and psychobehavioral disorders (CitationFabris et al 1988; CitationSong and Bao 1991; Saito et al 1994; CitationZhang et al 1994; CitationSpangelo 1995; CitationAntoniou et al 1997; CitationWang and Spitzer 1997; CitationTurrini et al 1998; CitationSavino and Dardenne 2000; CitationNishiyama 2001; CitationMorale et al 2003; CitationCavalloti et al 2005). These findings confirm that our results have solid physiopathological reasons and represent more than a fortuitous association.

In line with this notion, our data also indicate for the first time that alcohol-induced impaired mental status in HIV positive subjects is, at least in part, mediated by its effects over the thymus. Findings indicated that thymus atrophy is more evident in hazardous alcohol users and that the deleterious effect on the thymus impacts learning and memory ability. This is in accord with publications in the 1980s and early 1990s that alcohol use affects the size and weight of the thymus in animal models and in infants exposed to alcohol in utero (CitationSong and Bao 1991; Saito et al 1994; CitationZhang et al 1994; CitationWang and Spitzer 1997). Potential mechanisms mediating alcohol-induced thymic alterations include apoptotic changes, impaired mitochondrial function, and decreased total glutathione and antioxidant concentrations in thymocytes (CitationSong and Bao 1991; Saito et al 1994; CitationZhang et al 1994; CitationWang and Spitzer 1997). Possible interactive effects of ethanol and HIV infection in the CNS have been explored through studies of oxidative stress and interleukins. Findings from these studies reveal that both alcohol and HIV may increase oxidative stress in the brain and produce pro-inflammatory and TH2 interleukins (CitationMeyerhoff 2001). These results are of relevance to our findings, as the thymus regulates a number of the interleukins and thymic hormones, which have been demonstrated to reduce damage induced by oxidative stress in the CNS (CitationFabris et al 1988; CitationSong and Bao 1991; Saito et al 1994; CitationZhang et al 1994; CitationWang and Spitzer 1997; CitationSpangelo 1995; CitationAntoniou et al 1997; CitationTurrini et al 1998; CitationSavino and Dardenne 2000; CitationNishiyama 2001; CitationMorale et al 2003; CitationCavalloti et al 2005).

Before HAART, patients with HIV-associated dementia (HAD) typically experienced rapid deterioration over a few months (CitationSuarez et al 2001; CitationMcArthur et al 2005). HAART has played a major role in modifying the course of HAD (CitationMcArthur et al 2005). Encouragingly, our data, along with others, indicate some improvements in neuropsychological test performance abnormalities after starting HAART, but progress is not observed in all participants who were receiving and maintained adherence to HAART (CitationMcArthur et al 2005). The mechanism hindering HAART’s beneficial responses in some subjects, but not in others, remains largely unclear (CitationMcArthur et al 2005). Of interest, improvements in cognitive tasks after 6 months of HAART in our study were not associated with viral loads, CD4 counts, or age, but rather with thymus restoration, which is undermined by alcohol consumption. These findings further confirm our hypothesis regarding the role of thymus in the CNS.

Although the HDS and the CVLT cannot solely determine the presence of dementia in HIV-infected subjects, study participants were limited to those followed at University of Miami facilities, and MR was obtained only in a sub-sample of participants, our findings do illustrate the relationship between the thymus and neuropsychological functioning in both HIV disease and alcohol abuse, which was overlooked until now. These exciting results have improved understanding of the neuro-immune systems. The findings reported here should be tested with a comprehensive cognitive battery and, if supported by further studies, may have important clinical and therapeutic implications for neuroimmune diseases, when considering that several pathways manipulate the thymus and thymus-related substances.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Steven Reiman, MD and Janine Katzen, MD for their assistance with the MR image analysis. The study was funded by the NIAAA of the United States (5R21AA13793-3 MJM). The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- AntoniouKPapadopoulou-DaifotisZKanelakisK1997Relationship between the thymus and neurochemical changes in the hypothalamus-preoptic area and prefrontal cortex in female rats with delayed pubertyIntl J Dev Neurosc1591120

- BeanP2001HIV and alcohol use: consequences of comorbidityAmer Clin Lab20136

- CavallotiDD’AndreaVPastoreFS2005Pathogenesis of some neurological immune ultrastructural and morphometrical observations on rat thymusNeurol Res2741615829157

- DalakasMCTrappBD1986Thymosin β4 is a shared antigen between lymphoid and oligodendrocites of normal human brainAnn Neurol19349553085577

- De GeerGWebbWRGamsuG1986Normal thymus: assessment with MR and CTRadiology158313173941858

- DelisDCKramerJHKaplanE1987California verbal learning test: adult versionThe Psychological CorporationHarcourt BraceJovanovich, Inc

- DoughertyRHSkolaskyRLMcArthurJ2002Progression of HIV-associated dementia treated with HAARTAIDS Read12697411905143

- EwaldSJFrostWW1987Effect of prenatal exposure to ethanol on development of the thymusThymus921153499687

- FabrisNMocchegianiEMuzzioliM1988Neuroendocrine-thymus interactions: perspectives for intervention in agingAnn NY Acad Sci52172873288046

- FlemingM2005Screening and brief intervention in primary care settings [online]. Accessed January 28, 2007. URL: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh28-2/57-62.pdf

- McArthurJCBrewBJNathA2005Neurological complications of HIV infectionThe Lancet Neurology454355

- MeyerhoffDJ2001Effects of Alcohol and HIV Infection on the Central Nervous SystemAlcohol Res Health252889811910707

- MoraleMCGalloFTiroloC2003The reproductive system at the neuroendocrine-immune interface: focus on LHRH, estrogens and growth factors in LHRH neuronglial interactionsDomest Anim Endocrinol25214612963097

- NishiyamaN2001Thymectomy-induced deterioration of learning and memoryCellular and Molecular Biol471615

- PowerCSelnesOAGrimJA1995HIV dementia scale: a rapid screening testJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol8273787859139

- SaitoHNishiyamaNZhangY1997Learning disorders in thymectomized mice: a new screening model for cognitive enhancerBehav Brain Res836399062662

- SavinoWDardenneM2000Neuroendocrine control of thymus physiologyEndocr Rev214124310950159

- SongCBaoSW1991The Relationship between catecholamine and thymopeptides in ageing brainJ Gerontol1137073

- SpangeloB1995The thymic-endocrine connectionJ Endocrinol1475107490536

- SuarezSBarilLStankoffB2001Outcome of patients with HIV-1-related cognitive impairment on highly active antiretroviral therapyAIDS1519520011216927

- TurriniPTirassaPVignetiE1998A role of the thymus and thymosin-alpha1 in brain NGF levels and NGF receptor expressionJ Neuroimmunol8264729526847

- WangJFSpitzerJJ1997Alcohol-induced thymocyte apoptosis is accompanied by impaired mitochondrial functionAlcohol14991059014030

- WatzlBLopezMShahbazianM1993Diet and ethanol modulate immune responses in young C57BL/6 miceAlcohol Clin Exp Res17623308333593

- World Health Organization2005Worldwide HIV and AIDS Epidemic Statistics [online]. Accessed January 28, 2007. URL: http://www.avert.org/worlstatinfo.htm

- ZhangYSaitoHNishiyamaN1994Thymectomy-induced deterioration of learning and memory in miceBrain Res658127347834333