Abstract

Biologics have advanced the therapy of adult and pediatric arthritis. They have been linked to rare serious adverse outcomes, but the actual risk of these events is controversial in adults, and largely unknown in pediatrics. Because of the paucity of safety and efficacy data in children, pediatric rheumatologists often rely on the adult literature. Herein, we reviewed the adult and pediatric literature on five classes of medicines: Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, anakinra, rituximab, abatacept, and tocilizumab. For efficacy, we reviewed randomized controlled studies in adults, but did include lesser qualities of evidence for pediatrics. For safety, we utilized prospective and retrospective studies, rarely including reports from other inflammatory conditions. The review included studies on rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis, as well as juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Overall, we found that the TNF inhibitors have generally been found safe and effective in adult and pediatric use, although risks of infections and other adverse events are discussed. Anakinra, rituximab, abatacept, and tocilizumab have also shown positive results in adult trials, but there is minimal pediatric data published with the exception of small studies involving the subgroup of children with systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis, in whom anakinra and tocilizumab may be effective therapies.

Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) affects between 1:1000–1:2000 children (CitationManners and Bower 2002). This condition is heterogeneous, divided into several subtypes based upon various clinical, laboratory, and epidemiological features (CitationPetty et al 2004). Untreated, JIA can last well into adulthood, causing significant long-term functional impairment (CitationMinden et al 2000).

The last 10–15 years have witnessed an explosion in the development and application of medicines designed to target specific cytokines or cell surface receptors, therapies broadly referred to as biologics (CitationSiddiqui 2007). In addition, etanercept, adalimumab, and abatacept all have indications for JIA; summarizes the biologics currently used or under consideration for JIA. Multiple biologics have been approved for use in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) as well as the spondyloarthropathies (SpA), including ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) (CitationSiddiqui 2007). In addition, etanercept, adalimumab, and abatacept all have indications for JIA. summarizes the biologics currently used or under consideration for use in JIA.

Table 1 Biologics used in adult and pediatric arthritis. Adapted from CitationGartlehner and colleagues (2008)

This article is intended as a comprehensive review on the potential role of biologic therapy in pediatric arthritis. In contrast to previous review articles on this topic (CitationHashkes and Laxer 2006; CitationLovell 2006; CitationGartlehner et al 2008), however, we have elected to include data from adult studies as well. With respect to effectiveness data, this decision is justified in part by the likely genetic and mechanistic similarities between certain categories of JIA and their adult counterparts, such as RF-positive polyarticular JIA and RA; and enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) and adult SpA (CitationFerucci et al 2005; CitationGensler and Davis 2006; CitationSaxena et al 2006). In light of these similarities and the paucity of randomized trials in pediatrics, adult data is often the basis for our treatment decisions. Indeed, it was recently argued that the resources of pediatric rheumatology, both financial and patient, are limited and might be put to better use than duplicating studies of therapies already proven successful in adults (CitationLehman 2007). We have therefore incorporated data from randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled studies from both adult and pediatric populations. Because of the limited numbers of pediatric randomized trials, we have also presented lesser quality data exclusively involving pediatric patients, such as cohort and retrospective studies.

Similarly, safety data from adult patients often has implications in the pediatric population, perhaps even more so than effectiveness data, since the safety of therapy probably does not depend upon the mechanism of the underlying disease. Consequently, pediatric rheumatologists should be aware of the lessons learned from our adult counterparts. We have therefore incorporated safety data from both the adult and pediatric literature from various sources, including randomized trials, registries, other large cohort studies, and case reports. Because of the heterogeneity of JIA, we have included adult safety and efficacy data obtained from both RA and SpA patients.

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors

Basic scientific rationale

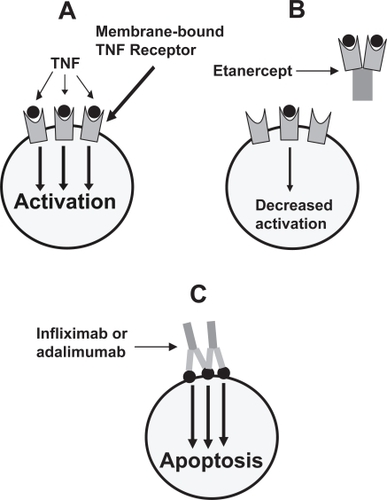

A potential role for TNF in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis was initially reported in the 1980s (CitationHopkins and Meager 1988), and testing of a monoclonal antibody to TNF was begun in the mid-1990s. At present, there are three anti-TNF therapies available (). Etanercept, a fusion protein consisting of the extracellular ligand-binding protein of the human 75-Kd TNF receptor linked to the Fc portion of human IgG1, is approved for RA, JIA (for patients 2–17 years old), PsA, AS, and plaque psoriasis (CitationZhou 2005). Infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody consisting of a murine immunoglobulin variable region directed against TNF fused with a human IgG1 Fc region, is approved for RA, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, AS, PsA, and plaque psoriasis (CitationFeldmann et al 2004). Adalimumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody consisting of a variable region directed against TNF fused with a human Fc created from a phage display of human components, is approved for use in RA, PsA, AS, JIA, and Crohn’s disease (CitationFeldmann et al 2004). As shown in , the fusion protein etanercept differs in its mechanism of action from the monoclonal antibodies infliximab and adalimumab; the significance of this difference in the treatment of arthritis and other rheumatological conditions is unclear (CitationRigby 2007).

Figure 1 Mechanism of action of the TNF inhibitors. The binding of soluble TNF to its membrane-bound receptor induces cellular activation and inflammation (A) Soluble TNF receptor fused to human Ig (etanercept) serves as a decoy receptor, binding to soluble TNF and preventing the TNF from binding to its membrane-bound receptor (B) The anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies bind to membrane-bound TNF, inducing apoptosis of cells involved in the inflammatory pathway (C) Adapted from CitationRigby (2007).

Effectiveness

All told, at least 35 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated the three TNF inhibitors to be effective in the treatment of arthritis, including the spondyloarthropathies, all but one of which involved the adult population (CitationElliott et al 1994; CitationRankin et al 1995; CitationMoreland et al 1997; CitationMaini et al 1998; CitationMoreland et al 1999; CitationWeinblatt et al 1999; CitationKavanaugh et al 2000; CitationLipsky et al 2000; CitationLovell et al 2000; CitationMease et al 2000; CitationVan Den Bosch et al 2002; CitationBrandt et al 2003; CitationDavis et al 2003; CitationFurst et al 2003; Citationvan de Putte et al 2003; CitationWeinblatt et al 2003; CitationCalin et al 2004; CitationKeystone et al 2004a, Citation2004b; CitationKlareskog et al 2004; CitationLan et al 2004; CitationSt Clair et al 2004; CitationTaylor et al 2004; Citationvan de Putte et al 2004; CitationAntoni et al 2005a, Citation2005b; CitationMarzo-Ortega et al 2005; CitationMease et al 2005; CitationQuinn et al 2005; Citationvan der Heijde et al 2005; CitationAbe et al 2006; CitationBreedveld et al 2006; Citationvan der Heijde et al 2006b; CitationWesthovens et al 2006; CitationGenovese et al 2007). To our knowledge, no negative studies have been published in the adult population, a record demonstrating the impressive effectiveness of this class of medicines in the management of inflammatory arthritis. Recently, a negative trial was published in pediatrics; this will be discussed in detail below (CitationRuperto et al 2007).

Several nonrandomized studies have evaluated etanercept in refractory JIA, generally finding it to be safe and effective (CitationKietz et al 2002; CitationLahdenne et al 2003; CitationQuartier et al 2003; CitationHenrickson and Reiff 2004; CitationHorneff et al 2004). In the largest of these studies, the German etanercept registry, 322 children with JIA were followed for a median of 12 months, with significant improvements reported in each of the response criteria studied (swollen and tender joint counts, joints with limited range of motion, morning stiffness, physician and patient global assessment, CHAQ, and ESR), with remission reported in 26% (CitationHorneff et al 2004). Overall, treatment was well-tolerated, although there were 12 severe adverse events, including one case each of pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation, thyroid cancer, and demyelination (CitationHorneff et al 2004). CitationKietz and colleagues (2002) prospectively studied 22 children with polyarticular course JIA for a median of 21 months, finding substantial improvement in clinical and laboratory parameters in this cohort; treatment was well-tolerated, with side effects limited to mild injection site reactions (CitationKietz et al 2002). Importantly, while CitationKietz and colleagues (2002) and CitationHorneff and colleagues (2004) both reported prolonged duration of effectiveness, a different group reported rapid but nonsustained improvement; for example, ACR-30 scores were reported in 73% at 3 months, compared with only 39% at 12 months. In addition, 12 of 61 patients in the latter study discontinued treatment because of severe adverse events, including pancytopenia, psychiatric disorders, uveitis, onset of inflammatory bowel disease, optic neuritis, headaches, vasculitis, and weight gain (CitationQuartier et al 2003).

The first published randomized trial of a TNF inhibitor in JIA involved etanercept. CitationLovell and colleagues (2000) enrolled 69 children 4–17 years of age with active polyarticular-course disease despite treatment with methotrexate into the initial open-label phase of the trial. After three months, the 51 children in whom improvement was noted were enrolled into the four-month double blind phase, with the endpoint being disease flare or 120 days, whichever occurred first; of these 51 children, 25 were randomized to etanercept, and the remainder received placebo injections. Results at the end of the double-blind phase revealed disease flares occurred in 81% of placebo-treated children, compared with 28% of etanercept-treated children (p < 0.05), with median times to flare of 28 and116 days, respectively (p < 0.05). There were no statistically significant differences in adverse events during the blinded portion of the study, although two etanercept-treated children were hospitalized: one for depression, and the other for gastroenteritis (CitationLovell et al 2000).

Children who completed the double-blind phase were eligible to enroll into the second open-label phase; 58 children entered into the extension study, and 32 completed four years. CitationLovell and colleagues (2006b) reported improvements in all measures of disease activity and decreased corticosteroid usage among the children participating in the extension study, including those who did not complete the four-year study. Etanercept was generally well-tolerated; overall, there were 225 patient-years of follow-up, with 8 serious infections, for a rate of 3 per 100 person-years. There were no lupus-like events, demyelinating lesions, or malignancies (CitationLovell et al 2006b). Thus, etanercept appears to be safe and effective for longterm use in JIA. However, this study was faulted for bias introduced by the three-month run-in period, as well as for its failure to adjust for baseline differences between the groups, such as older age, longer disease duration, increased RF positivity, and increased corticosteroid usage among the control groups, differences that could bias towards showing an increased effect (CitationGartlehner et al 2008).

With respect to infliximab, there are several uncontrolled retrospective and prospective studies, beginning with the case report by Elliot and colleagues (CitationElliott et al 1997; CitationLahdenne et al 2003; CitationSchmeling and Horneff 2004; CitationGerloni et al 2005; CitationDe Marco et al 2007; CitationNorambuena et al 2007). The three prospective studies generally showed effectiveness among those who tolerated it, although infusion reactions caused frequent discontinuations. For example, CitationGerloni and colleagues (2005) reported significant improvements in the core measures of disease activity among 24 young adults with persistently active polyarticular JIA after 24 months of therapy, although six of the 24 dropped out (5 because of infusion reactions and one because of disease relapse), and 9 others did not complete two years of observation for unstated reasons. CitationLahdenne and colleagues (2003) enrolled 14 polyarticular children, reporting ACR-75 improvements among six of nine treated with infliximab for one year, although a total of six withdrew within the first eight months: three because of infusion reactions, one with alopecia, one with macrophage activation syndrome, and one because of lack of efficacy (CitationLahdenne et al 2003). Finally, Citationde Marco and colleagues (2007) treated 78 JIA patients with infliximab for up to three years, finding significant and long-lasting improvements in the majority, but also reporting that 26 discontinued because of adverse events, most commonly infusion reactions (CitationDe Marco et al 2007).

The results of a randomized controlled trial of infliximab in JIA were published in 2007. In this study, children with active arthritis were randomized to receive either placebo for 14 weeks, followed by infliximab 6 mg/kg at weeks 14, 16, 20, and every 8 weeks thereafter for a total of 44 weeks; or infliximab 3 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, 6, and 14, followed by placebo at week 16, then 3 mg/kg again at week 20 and every 8 weeks thereafter. All patients received methotrexate co-therapy throughout the study period. At week 14, the duration of the placebo-controlled portion of the study, more children in the 3 mg/kg group achieved an ACR-30 response compared with the placebo group (37 of 58 [63.8%] vs 29 of 59 [49.2%]), but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.12), so the study failed to achieve its primary aim. Nevertheless, at week 14, children the infliximab group had significantly fewer joints with active arthritis. At the end of the 52-week study period, there were no significant differences between the two treatment groups in the core set components (CitationRuperto et al 2007).

Safety analysis from the infliximab study revealed that children in the low-dose infliximab group were more likely to generate anti-infliximab antibodies compared with those in the 6 mg/kg group, and were also more likely to have infusion reactions. Serious adverse events occurred in 19 of 60 patients over 52 weeks treated with 3 mg/kg infliximab, 3 of 60 placebo patients over 14 weeks, and 3 of 57 patients over 38 weeks treated with 6 mg/kg infliximab, so that after adjusting for length of treatment, they were most common in the low-dose infliximab group and least common in the high-dose group. There were six serious infections, including one case of asymptomatic pulmonary tuberculosis, in the infliximab-treated groups compared with two in the placebo patients; the authors did not adjust for length of treatment, but it appears that after doing so, no increased risk associated with drug therapy would be apparent. One placebo patient died of sepsis during the study; one infliximab-treated patient with systemic onset JIA (SOJIA) died during the open-label phase of the study, six months after the final dose, from cardiac complications of the underlying disease. No malignancies were reported (CitationRuperto et al 2007).

Finally, there is emerging evidence that adalimumab may also be effective in JIA. CitationBiester and colleagues (2007) reported on 16 patients with JIA who had previously failed treatment with conventional DMARDs and other TNF inhibitors, finding a good response in 10, and a mild response in three (CitationBiester et al 2007). In addition, data from a Phase III clinical trial of adalimumab in JIA presented at the 2006 American College of Rheumatology conference, but not yet published, revealed significantly higher clinical responses to the study drug compared with placebo, albeit with 4 unspecified serious adverse events compared with two in the placebo arm (CitationLovell et al 2006a).

For older children, pediatric dosing of the TNF inhibitors is similar to that used in adult medicine. The initial etanercept trials in adults used doses of 25 mg subcutaneously twice weekly (CitationBrandt et al 2003; CitationDavis et al 2003; CitationCalin et al 2004), while the JIA trial used a dose of 0.4 mg/kg twice weekly, maximum of 25 mg per dose (CitationLovell et al 2000). However, because a single 50 mg dose has been shown to be equally effective in adults with rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis, the latter is often used in adult rheumatology (CitationKeystone et al 2004b; Citationvan der Heijde et al 2006a). This dose has not been formally studied in pediatrics, but two small case series have shown that it may be equally effective (CitationKuemmerle-Deschner and Horneff 2007; CitationPrince et al 2007), and many practitioners have altered their practice accordingly. Dosing used in the unpublished adalimumab trial was 24 mg/m2 (CitationLovell et al 2006a), maximum of 40 mg every other week, the standard adult dose (CitationBreedveld et al 2006). Pediatric and adult dosing of infliximab is typically 3–10 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6 and q4–8 weeks thereafter (CitationLahdenne et al 2003; CitationSt Clair et al 2004; CitationDe Marco et al 2007; CitationRuperto et al 2007).

The role of methotrexate co-therapy in pediatric patients using TNF inhibitors is uncertain. Randomized trials among adult patients with RA have shown that all three TNF inhibitors are more effective as co-therapy with methotrexate than they are as mono-therapy (CitationMaini et al 1998; CitationKlareskog et al 2004; CitationBreedveld et al 2006). In the etanercept JIA trial, methotrexate was discontinued at the onset of the trial in all patients as per protocol, so no comparisons were available from this study, while in the infliximab trial, all patients received methotrexate (CitationLovell et al 2000; CitationRuperto et al 2007). However, data from the German JIA etanercept registry revealed that patients treated with etanercept and methotrexate in combination, compared with those treated with etanercept alone, were more likely to achieve complete remission (29% vs 14%, p = 0.07) (CitationHorneff et al 2004). Regarding safety, there are advantages to combining infliximab with methotrexate or other disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs); combination therapy appears to protect against the development of anti-infliximab antibodies, which have the unfortunate effects of inducing potentially dangerous infusion reactions and lessening the effectiveness of the therapy (CitationCheifetz and Mayer 2005; CitationBendtzen et al 2006). In practice, therefore, many pediatric practitioners use methotrexate as co-therapy with TNF agents in the treatment of RA and JIA, particularly when administering infliximab.

The usefulness of methotrexate co-therapy in SpA remains unknown, as no trials have compared TNF inhibitors alone with TNF inhibitors plus conventional DMARDs (CitationBraun et al 2006). There is retrospective data, however. In a retrospective study of infliximab-treated patients with inflammatory arthritis, CitationKapetanovic and colleagues (2006) reported that absence of DMARD co-therapy was a risk factor for infusion reactions in RA, but not SpA, patients. However, there were only 76 SpA patients, and the negative findings in this group may have been due to a lack of statistical power, since 7 of 10 patients with infusion reactions were using infliximab mono-therapy, while such patients constituted only 41% of all infliximab-treated SpA patients (CitationKapetanovic et al 2006). In addition, data in Crohn’s disease suggests that methotrexate can reduce the immunogenicity of infliximab therapy (CitationBaert et al 2003). Thus, when initiating infliximab therapy in SpA patients, some practitioners will prescribe low-dose methotrexate therapy with the primary aim of preventing infusion reactions, regardless of whether the added therapy will have an additive treatment effect. However, methotrexate co-therapy is not routinely used with etanercept.

Enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) is a subtype of JIA that has clinical and genetic features similar to the adult spondyloarthropathies (CitationBurgos-Vargas et al 2002a). Uncontrolled studies have demonstrated TNF inhibition to be effective for this particular sub-group (CitationHenrickson and Reiff 2004; CitationTse et al 2005). For example, CitationHenrickson and Reiff (2004) demonstrated effectiveness in 8 children with ERA (age 8–16 years) treated with etanercept for one year in one patient and in two years in seven others. CitationTse and colleagues (2005) reported a good response in 10 children followed for one year (CitationTse et al 2005). Finally, CitationBurgos-Vargas and colleagues (2007) presented data at the 2007 ACR conference of a randomized study of 26 children with ERA favoring infliximab over placebo therapy. This parallels the success of TNF inhibition in adult SpA (CitationMease et al 2000; CitationVan Den Bosch et al 2002; CitationBrandt et al 2003; CitationDavis et al 2003; CitationCalin et al 2004; CitationAntoni et al 2005a, Citation2005b; CitationMarzo-Ortega et al 2005; CitationMease et al 2005; Citationvan der Heijde et al 2005, Citation2006a, Citation2006b; CitationGenovese et al 2007). Importantly, adults with axial arthritis have generally demonstrated a poor response to conventional DMARDs, and an international consensus group recommended that TNF inhibitors be used as first line therapy for patients with axial disease (CitationSampaio-Barros et al 2000; CitationBraun et al 2006; CitationChen and Liu 2006; CitationHaibel et al 2007). Although two studies of children with juvenile SpA have demonstrated modest benefit of sulfasalazine therapy, neither of them differentiated those with axial symptoms from those with peripheral disease (CitationHuang and Chen 1998; CitationBurgos-Vargas et al 2002b), and there is no data showing that traditional DMARDs are effective in the axial disease of ERA. Thus, our practice is to follow the adult spondyloarthritis guidelines and use TNF inhibitors as first-line therapy, bypassing the conventional DMARDs. As noted above, however, when using infliximab, we may use methotrexate as co-therapy to decrease the risk of infusion reactions.

Although TNF inhibitors have been generally effective in polyarticular JIA and ERA, they have been less so in SOJIA (CitationBilliau et al 2002; CitationRusso et al 2002; CitationKatsicas and Russo 2005; CitationKimura et al 2005). The first TNF inhibitor to be reported for treatment of this illness was etanercept. CitationKimura and colleagues (2005) reviewed 82 patients treated with etanercept, finding a good or excellent response in 46% and a poor response in 45% (CitationKimura et al 2005). Likewise, CitationRusso and colleagues (2002) reported their experience with 15 children with SOJIA; 14 of them did enjoy an initial response, but relapses were observed in nine, particularly when the doses of concomitant steroids and methotrexate were lowered (CitationRusso et al 2002). Two observational studies comparing etanercept in children with different subtypes of JIA have found that the drug is less effective in children with systemic-onset disease compared with the other JIA subtypes, as did the randomized trial (CitationLovell et al 2000; CitationQuartier et al 2003; CitationHorneff et al 2004). Infliximab as well has generally been unsatisfying, particularly with respect to the systemic symptoms (CitationBilliau et al 2002; CitationKatsicas and Russo 2005). There is no data comparing the two, although our experience has been that infliximab may be more effective. However, neither has been shown to be particularly effective, and as will be discussed below, therapies targeting interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 have generally shown more promise.

It has long been understood that a dangerous complication of pediatric arthritis is uveitis (CitationSchaller et al 1969). Although initial case reports did show limited success with treatment with etanercept (CitationReiff et al 2001), subsequent studies have not borne this out (CitationSchmeling and Horneff 2005; CitationSmith et al 2005; CitationSaurenmann et al 2006). Indeed, a small controlled study enrolling 12 pediatric patients with uveitis found that the seven who received etanercept had no better response than the five who received placebo (improvement was noted in three of seven etanercept-treated patients, versus two of five placebo patients) (CitationSmith et al 2005). In contrast, infliximab has been reported to be effective for uveitis in several case reports (CitationRichards et al 2005; CitationKahn et al 2006; CitationRajaraman et al 2006), with small comparative studies demonstrating it to be more effective than etanercept (CitationSaurenmann et al 2006; CitationFoeldvari et al 2007; CitationTynjala et al 2007). CitationFoeldvari and colleagues (2007) surveyed the international pediatric rheumatology community, obtaining responses from 15 centers in which TNF inhibitors were used for this indication. The 15 centers entered 47 patients into this retrospective analysis, reporting a good / moderate / poor response of 68%/32%/0% for infliximab, versus 47%/15%/38% for etanercept, a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05). In this study, only three children used adalimumab, all of whom demonstrated a good response (CitationFoeldvari et al 2007). Likewise, CitationTynjala and colleagues (2007) reported on their experiences in the management of pediatric JIA-associated uveitis at a single center, finding treatment failure in 54% of etanercept-treated patients versus 19% in the infliximab group (CitationTynjala et al 2007). Lastly, CitationSaurenmann and colleagues (2006) performed a retrospective study of 21 children treated with TNF inhibitors for uveitis, finding that infliximab was significantly more likely to induce a moderate or good response compared with etanercept (CitationSaurenmann et al 2006). In the randomized trial of infliximab in JIA, uveitis was an exclusion criteria, so its use was not evaluated in this population (CitationRuperto et al 2007). Two recent case series have found that adalimumab was effective in the management of pediatric uveitis (CitationVazquez-Cobian et al 2006; CitationBiester et al 2007). CitationBiester and colleagues (2007) reported that 16 of 18 children with uveitis responded well to adalimumab, while CitationVazquez-Cobian and colleagues (2006) reported decreased ocular inflammation in 12/14 children, with improved vision and decreased use of topical steroids in the other two patients. Thus, treatment with one of the TNF inhibitor monoclonal antibodies has become the standard of care for children with uveitis who failed DMARD therapy.

Safety

Perhaps the most feared complication of TNF inhibitors is infection. There have been a considerable number of case reports and case series describing serious or opportunistic infections, including Pneumocystis jivoreci and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), among adult and pediatric patients taking TNF inhibitors (CitationGomez-Reino et al 2003; CitationArmbrust et al 2004; CitationKinder et al 2004; CitationTubach et al 2006; CitationKaur and Mahl 2007; CitationKesteman et al 2007), and national surveillance data from Spain confirmed an increased risk of MTB relative to the background rate associated with RA (CitationGomez-Reino et al 2003; CitationKesteman et al 2007). Various groups internationally have established treatment guidelines regarding the risk of MTB, requiring all patients treated with TNF inhibitors to receive a PPD in advance of therapy, and those with positive tests or historical or clinical signs of MTB treated for the infection prior to initiation of TNF inhibitor therapy (CitationFurst et al 2002; CitationMariette and Salmon 2003; CitationBTS 2005). Fortunately, these recommendations have been effective in reducing the risk of tuberculosis in RA patients treated with TNF inhibitors (CitationCarmona et al 2005).

Although there is a general recognition that TNF inhibitors can predispose to infectious complications, the magnitude of the risk is unclear. They have been generally well tolerated during the randomized trials, with few showing statistically significant increases in infections as compared with the placebo arm. Specifically, of the 36 trials referenced above, 34 reported safety data, and only two demonstrated a statistically significant increase in serious infections (generally defined as those which were life-threatening or resulted in hospitalizations) in the treatment versus the control arms (CitationKeystone et al 2004a; CitationSt Clair et al 2004) (). However, others revealed nonsignificant increases in infections in the drug arm (Citationvan de Putte et al 2004; CitationWesthovens et al 2006), and a meta-analysis published in 2006 limited to the two anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies and to RA trials did find an overall increased risk of serious infections (CitationBongartz et al 2006). This study has been criticized on methodological grounds for several reasons, including its exclusion of etanercept and its failure to take into account the longer duration of follow-up in the drug versus control arms in several of the studies (CitationDixon and Silman 2006). In addition, the definition of serious infections used in the varying trials was heterogeneous, and some of the patients may not have had infections that all clinicians would consider serious or life-threatening, such as bronchitis, community-acquired pneumonia, urinary tract infection, or cellulitis (CitationBongartz et al 2006). Thus, the data from the randomized controlled studies is suggestive, but not definitive, of an increased overall infection risk.

Table 2 Summary of TNF inhibitor trials in inflammatory arthritis

Important limitations of randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trials, particularly insofar as interpretation of safety data is concerned, include the small number of patients studied, the relatively short duration of follow-up, and the exclusion of patient who may be at increased risk of complications (CitationPincus and Stein 1997) Indeed, the percentage of patients in daily practice who would qualify for a randomized trial may be as low as 21%–33%, reflecting both lower disease activity and higher comorbidities in the excluded population (CitationZink et al 2006). Thus, large cohort data has been used to further evaluate the risk of TNF inhibitors in everyday practice. An important caveat of these studies is that TNF inhibitors are obviously preferentially used to treat patients with active disease, which is itself a risk factor for infection (CitationDoran et al 2002), thus it is essential that cohort studies adjust for such potential confounding factors. In addition, knowledge of a patient’s treatment status may affect a physician’s management of a possible or diagnosed infection. Despite these limitations, large, comparative observational studies have made important contributions to our understanding of the risks of treatment with TNF inhibitors and other therapies. Several studies have identified increased risks of serious infections, including those derived from 1459 patients in the German RA registry (CitationListing et al 2005); 23,733 patients in a Quebec cohort (CitationBernatsky et al 2007); 5,326 US patients identified through Medicare claims (CitationCurtis et al 2007); and two separate single-center chart reviews comparing individual patients before and after initiation of TNF inhibitor use (CitationKroesen et al 2003; CitationSalliot et al 2007). In contrast, three studies failed to show an increased infection risk: these were the British registry containing 8973 RA patients (CitationDixon et al 2006); a cohort of 16,788 patients enrolled in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases (which was limited to hospitalizations for pneumonia) (CitationWolfe et al 2006); and a population of elderly Medicare patients in Pennsylvania (CitationSchneeweiss et al 2007). It is difficult to reconcile these disparate results, although failure to adjust for corticosteroid usage (CitationListing et al 2005; CitationBernatsky et al 2007; CitationCurtis et al 2007) may explain some of these findings, since high doses of corticosteroid usage appear to be an important risk factor for infections (CitationWolfe et al 2006; CitationBernatsky et al 2007; CitationSalliot et al 2007; CitationSchneeweiss et al 2007). Alternatively, patients with increased risk of infections may not have been considered candidates for TNF inhibitors; infections in these high-risk patients could bias the results towards finding no difference between the DMARD and TNF inhibitor groups (CitationDixon et al 2006; CitationCurtis et al 2007). Also, failure to incorporate infections that occurred after TNF therapy was discontinued may lead to an underestimation of infection risk, if therapy was discontinued because of symptoms suggestive of infections, but not diagnosed as such at the time of discontinuation; this was found to be the case in post-hoc analysis of the data from the British registry (CitationDixon et al 2007). In addition, this post-hoc analysis also revealed that limiting the analysis to the first three months of therapy may reveal a sub-population of patients at increased risk of infection; since these patients often discontinue therapy, it follows that that the bulk of the patient-years of follow-up will be comprised of those who tolerated treatment well, thus potentially obscuring a signal (CitationDixon et al 2007). Indeed, analysis of the Swedish RA registry revealed that the relative risk of an infection leading to hospitalization associated with TNF inhibitor use decreases with each subsequent year of use (CitationAskling et al 2007).

With respect to pediatrics, the etanercept trial did not reveal any significant differences in the incidence of infections (CitationLovell et al 2000). Data from the four-year follow-up, as noted above, revealed 8 serious infections over 225 person-years; as described in the manuscript, these included gastroenteritis requiring hospitalization, aseptic meningitis secondary to varicella infection, sepsis, cellulitis requiring hospitalization for IV antibiotics, herpes zoster infection treated with IV acyclovir, appendicitis, a post-operative wound infection, and a dental abscess (CitationLovell et al 2006b). Likewise, the infliximab trial did not appear to reveal an increased risk of serious infections, after adjusting for different durations of treatment (CitationRuperto et al 2007). In addition, data from the German etanercept JIA registry consisting of 322 patients with 592 patient-years of follow-up revealed only 20 infectious events, none of which were opportunistic, although several were judged to be serious, including a case of sepsis (CitationHorneff et al 2004). There are no cohort studies comparing pediatric DMARD to TNF inhibitor treated patients; thus, while serious infections have been observed in pediatric patients taking TNF inhibitors, these are uncommon, and contributions from the disease itself or other therapies cannot be excluded.

A second side effect potentially attributed to use of TNF inhibitors is malignancy, particularly hematological (CitationBrown et al 2002; CitationGeborek et al 2005). This perhaps is not unexpected, since the cytokine Tumor Necrosis Factor derived its name from studies from the 1970s in which a factor derived from the serum of bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG)-immunized mice treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was shown to induce lysis of transplanted tumors (CitationCarswell et al 1975). Numerous studies have reported development of hematological malignancies among patients taking TNF inhibitors (CitationBrown et al 2002), with one report of the lymphoma regressing after TNF inhibitor and coexistent DMARD therapy were withdrawn (CitationThonhofer et al 2005). In practice, however, the actual risk of hematological malignancies may be limited. Of all the controlled studies referenced above, none of them actually demonstrated a statistically significant increased risk of malignancies, hematological or otherwise; only five revealed any hematological malignancies in the TNF inhibitor-treated patients, and none showed more than one (CitationLipsky et al 2000; CitationFurst et al 2003; CitationKeystone et al 2004a; CitationSt Clair et al 2004; CitationBreedveld et al 2006) (). The Bongartz meta-analysis did find an increased risk of malignancies among TNF inhibitor users in the RA infliximab and adalimumab trials (CitationBongartz et al 2006); however, in addition to the criticisms discussed above, it was also noted that the risk of malignancies in the control population was surprisingly low in those studies and may not have reflected the general population (CitationDixon and Silman 2006).

In addition, a number of cohort studies have evaluated the risks of malignancies among TNF inhibitor users compared with DMARD users or healthy controls, and the bulk of this data is reassuring. Three large cohort studies, including one in Sweden, one in the US and Canada, and one using data from 19,591 patients in the National Data Bank for Rheumatologic Diseases (NDB), have failed to find an increased risk of lymphoma or other malignancies among patients taking TNF inhibitors (CitationAskling et al 2005a, Citation2005b; CitationSetoguchi et al 2006; CitationWolfe and Michaud 2007b). There was one contradictory study from Sweden, which did find an increased risk of lymphoma (CitationGeborek et al 2005); importantly, this was criticized in an accompanying editorial for several reasons, such as incomplete controlling for disease severity and low numbers of lymphoma cases identified altogether, including an unusually low incidence in the control population (CitationFranklin et al 2005). In addition, more recent analysis of the NDB did show a small but statistically significant increased risk of skin cancer (CitationWolfe and Michaud 2007a). Thus, while active rheumatoid arthritis is a well-known risk factor for lymphoma (CitationBaecklund et al 2006; CitationFranklin et al 2006; CitationSetoguchi et al 2006), it appears that TNF inhibitors may not substantially increase the risk; indeed, it is plausible that to the extent that they are effective in lowering the inflammatory burden, they may even decrease the associated risk of malignancies, although this has note been borne out in studies (CitationWolfe and Michaud 2004). There may, however, be an increased risk of skin cancers; this will need to be re-evaluated in future studies (CitationWolfe and Michaud 2007a). Finally, the name TNF itself may be a misnomer; there is more recent data suggesting that the cytokine may actually promote cancer growth at physiological concentrations (CitationAnderson et al 2004).

With respect to pediatrics, neither of the published TNF inhibitor trials revealed any malignancies, including data reported in the four-year open-label follow-up of the etanercept study (CitationLovell et al 2000, Citation2006b; CitationRuperto et al 2007). CitationHorneff and colleagues (2004) did report a case of thyroid cancer in a 19 year-old woman with JIA from their etanercept registry, but to our knowledge, there are no published reports of malignancies among children under 18 years of age that were attributed to TNF inhibitors.

Finally, a handful of additional rare side effects have been reported among TNF inhibitor users: these include episodes of demyelination consistent with multiple sclerosis (CitationSicotte and Voskuhl 2001; CitationTanno et al 2006); development of lupus autoantibodies and lupus-like syndromes (CitationFerraro-Peyret et al 2004; CitationDe Bandt et al 2005; CitationFusconi et al 2007), occasionally associated with frank glomerulonephritis and other serious complications (CitationMor et al 2005; CitationChadha and Hernandez 2006); pulmonary nodulosis reversible upon discontinuation of etanercept and concomitant leflunomide therapy (Citationvan Ede et al 2007); development of psoriasis, vasculitis, and other autoimmune diseases (CitationPirard et al 2006; CitationSaint Marcoux and De Bandt 2006; CitationCohen et al 2007; CitationPrescott et al 2007; CitationRamos-Casals et al 2007; CitationVerschueren et al 2007); infusion reactions (CitationCrandall and Mackner 2003); and depression (CitationLovell et al 2000). Even in the pediatric population, cases of optic neuritis, vasculitis, demyelination, drug-induced lupus, and psoriasis have been reported (CitationLepore et al 2003; CitationQuartier et al 2003; CitationHorneff et al 2004; CitationPeek et al 2006), and as discussed above, discontinuations due to infusion reactions have been reported in 21%–22% of children enrolled in the three open-label infliximab studies (CitationLahdenne et al 2003; CitationGerloni et al 2005; CitationDe Marco et al 2007).

Summary

TNF inhibitors have been used to treat arthritis for over 10 years. In general, they have been found to be safe and effective in the adult and pediatric populations (CitationHorneff et al 2004; CitationKeystone 2005; CitationLovell et al 2006b). One notable exception is the recent infliximab trial in JIA, although it was argued in an accompanying editorial that this likely reflects study design and low patient numbers rather than an actual lack of efficacy in the pediatric population (CitationLehman 2007). In addition, TNF inhibitors have generally been disappointing in the management of the systemic symptoms of SOJIA (CitationKimura et al 2005). Among patients with JIA, there is scant data comparing specific TNF inhibitors, with the exception of findings of increased effectiveness of infliximab versus etanercept in the treatment of JIA-associated uveitis (CitationSaurenmann et al 2006; CitationFoeldvari et al 2007; CitationTynjala et al 2007). Perhaps the most significant risk of therapy in both adults and children is serious infections, including tuberculosis. Fortunately, the adoption of treatment guidelines have mitigated the risk of this particular infection (CitationCarmona et al 2005), but patients still do need to be cautioned about the risks of opportunistic and other serious infection.

Anakinra

Basic scientific rationale

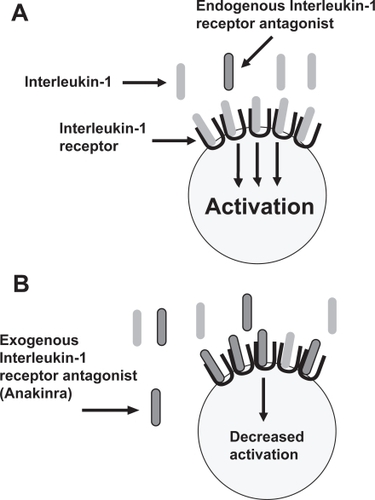

Interleukin-1 (IL-1) is a highly inflammatory cytokine which plays an important role in several inflammatory conditions, including RA and SOJIA (CitationDinarello 1996; CitationCohen 2004; CitationPascual et al 2005). The action of IL-1 is regulated by the naturally occurring IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra); this protein contains substantial sequence homology to IL-1, but rather than causing activation through the IL-1 receptor, serves as a competitive inhibitor to IL-1 and is believed to play an endogenous anti-inflammatory role (CitationThompson et al 1992). The IL-1Ra was cloned through recombinant technology from human monocytes in 1990 and modified by the addition of a methionine residue at the amino terminus to become the commercially available drug Anakinra (CitationEisenberg et al 1990; CitationCohen 2004) (). It was initially studied in RA in 1996 and approved for use in RA by the FDA in 2001 (CitationCampion et al 1996; CitationCohen 2004). Alternative methods for blocking IL-1 are under investigation, but this is beyond the scope of this review.

Figure 2 Mechanism of action of anakinra. IL-1 binds to its receptor, inducing cellular activation and inflammation (A) Exogenous IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra; Anakinra) competes with IL-1 for binding to its receptor but does not induce cellular activation and inflammation (B).

Effectiveness

There have been three placebo-controlled trials in RA studying safety and efficacy of anakinra, and a fourth that evaluated safety only, the most frequently used dose being 100 mg daily; in two of the studies, all patients were treated with methotrexate, a third required discontinuation of methotrexate therapy, and the safety trial allowed for individual differences (CitationBresnihan et al 1998; CitationCohen et al 2002, Citation2004; CitationFleischmann et al 2003). All three trials demonstrated moderate clinical benefit, and improvements in radiographic progression were also documented (CitationBresnihan et al 1998; CitationJiang et al 2000; CitationCohen et al 2002, Citation2004; CitationFleischmann et al 2003). However, although there are no randomized head-to-head comparisons of TNF inhibitors with anakinra, a recent review of the existing studies reported that the TNF inhibitor trials generally reported better ACR responses compared with the anakinra trials (CitationGartlehner et al 2006).

The primary use of anakinra in the JIA population is in the treatment of patients with SOJIA, particularly during the systemic phase of the illness. The effectiveness of anakinra in therapy-resistant SOJIA was first reported in 2004 in an abstract presented at the American College of Rheumatology by CitationIrigoyen and colleagues (2004), who surveyed the pediatric rheumatology community and summarized the experiences of seven patients from five centers, reporting overall improvements in inflammatory markers and arthritis. CitationVerbsky and White (2004) reported their experiences in two patients, both of whom experienced rapid and sustained resolution of symptoms at a dose of 2 mg/kg. CitationPascual and colleagues (2005) demonstrated prompt and dramatic improvement in both clinical and laboratory parameters in nine patients with refractory SOJIA. In this study, anakinra (2 mg/kg, maximum 100 mg) induced resolution of systemic symptoms within the first week of treatment in seven of seven patients, as well as resolution of arthritic symptoms within days to weeks in six of eight patients; the remaining two patients had a partial response of their arthritis (CitationPascual et al 2005). Likewise, there have been several reports of the use of anakinra in patients with the adult counterpart, adult-onset Still’s disease (CitationFitzgerald et al 2005; CitationVasques Godinho et al 2005; CitationKalliolias et al 2007; CitationKotter et al 2007). Virginia Pascual has provided scientific rationale of such therapy, showing upregulation of IL-1 related gene products in children with active SOJIA, trending toward the gene expression levels seen in healthy controls following treatment with anakinra (CitationPascual et al 2005; CitationAllantaz et al 2007).

Importantly, there have been negative findings as well. CitationOglivie and colleagues (2007) reported that only one of six children with SOJIA had responded to anakinra. However, it was not clear whether the patients in their study had at the time of the trial mostly systemic or articular features, and our experience has been that anakinra is more effective at treating symptoms in the systemic phase of the disease, compared with the later, articular phase (CitationPascual et al 2005).

Additionally, CitationLequerre and colleagues (2008) reported that only five of 20 children with SOJIA treated with 1–2 mg/kg/day of anakinra achieved ACR-50 improvements at six months of therapy. In this study, the mean duration of disease was seven years and only 60% of children had systemic symptoms at the time anakinra therapy was initiated, while the remainder of the children had diffuse and severe arthritis without fever or rash. This contrasts to the more favorable experience of CitationPascual and colleagues (2005) in which all but two children had systemic features, again suggesting that anakinra may be more effective in the earlier systemic phase of the disease than in the later articular phase.

There is minimal data of anakinra use in other JIA subtypes, none of which has been published to date. An open label study of 82 patients with polyarticular JIA presented only in abstract form, showed an ACR Pediatric 30 response in 58% of subjects (CitationIlowite et al 2003), a level which compares unfavorably with that reported in the open-label phase of the etanercept trial (~80%; CitationLovell et al 2000). In the double-blind phase of the anakinra trial, there were only small and nonstatistically significant improvements in the anakinra-treated compared with the placebo-treated patients (CitationIlowite et al 2006).

Safety

In general, treatment with anakinra, both as monotherapy and in combination with methotrexate, has been shown to be well-tolerated in both adults and children (CitationBresnihan et al 1998; CitationCohen et al 2002, Citation2004; CitationFleischmann et al 2003; CitationPascual et al 2005). Injection site reactions are the adverse effect most often reported and tend to be mild and improve over time (CitationBresnihan et al 1998; CitationPascual et al 2005). Patients should be cautioned that the injections themselves can be quite painful, however. In the study published by CitationPascual and colleagues (2005), one patient with underlying myocardial dysfunction developed two episodes of vomiting and hypotension with anakinra administration. Of the four randomized trials in RA, one did not report any serious infections (CitationCohen et al 2002), and two others found the risks between the placebo and anakinra arms to be similar (CitationBresnihan et al 1998; CitationCohen et al 2004). The largest of the four trials, enrolling 1399 patients, did find an increased risk of serious infections in the anakinra-treated patients (2.1% vs 0.4%), albeit not statistically significant. Most of the infections consisted of pneumonia or cellulitis; there were no opportunistic infections or cases of TB and none were fatal (CitationFleischmann et al 2003). A three-year update on this study revealed no significant changes in the rate of adverse events over this time frame (CitationFleischmann et al 2006). Transient cytopenias have also been reported in study patients, as well as anecdotally (CitationBresnihan et al 1998; CitationCohen et al 2002; CitationQuartuccio and De Vita 2007). Finally, anecdotal case reports of cardiac death in a 29 year-old woman with adult-onset Still’s disease, visceral leishmaniasis in a 9-year-old girl living in an endemic area in southeastern France, tuberculosis reactivation, and multiple-organism sepsis in a 66-year-old RA patient have been documented in patients taking anakinra (CitationTuresson and Riesbeck 2004; CitationKone-Paut et al 2007; CitationRuiz et al 2007; CitationSettas et al 2007).

Summary

Interleukin-1 blockade by anakinra interferes with the pro-inflammatory cascade important in the pathogenesis of chronic arthritis. Although its role in the therapy of RA and polyarticular JIA is undefined, anakinra is generally well-tolerated and does appear to be very effective in treating the systemic features of SOJIA (CitationPascual et al 2005). However, because the pediatric studies were based upon small groups of children, overall pediatric safety data is limited.

Rituximab

Basic scientific rationale

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 surface antigen present on B-cells; it consists of a human IgG1 heavy chain fused to a murine anti-CD20 variable receptor (CitationGrillo-Lopez et al 1999). The CD20 receptor is present on pre-B, naïve, memory, and mature B-cells, but not on plasma cells or stem cells, nor on any other cell lineages, hence the specificity of rituximab for B-cells (CitationLeandro et al 2002). Approved by the FDA for use in CD20+ B-cell lymphomas in 1997, it has since been applied to a variety of autoimmune diseases, perhaps most prominently RA. The FDA approved it for use in RA refractory to TNF inhibitors in 2005 (CitationSmolen et al 2007).

Effectiveness

Compared with the TNF inhibitors, the amount of safety and effectiveness data for rituximab in RA is limited. There have been two randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials in RA, both of which showed statistically significant beneficial effects, as did a randomized, placebo-controlled, open-label trial; dosages used in these studies were 500 mg or 1000 mg IV x two doses, two weeks apart (CitationEdwards et al 2004; CitationCohen et al 2006; CitationEmery et al 2006). Additional important information that has emerged from these trials includes effectiveness of rituximab in patients who have failed TNF inhibitors, increased tolerance of the infusion when patients are pre-medicated with methylprednisolone, and lack of an additive effect with daily oral corticosteroids or with cyclophosphamide infusions (CitationEdwards et al 2004; CitationCohen et al 2006; CitationEmery et al 2006). In addition, in all three trials, nearly complete B-cell depletion was noted in the rituximab-treated patients, with recovery in two of the studies noted beginning at 16 weeks (CitationEdwards et al 2004; CitationCohen et al 2006; CitationEmery et al 2006). Additional information about the kinetics of B-cell recovery was obtained by CitationLeandro and colleagues (2006), who observed that B-cell repopulation in a cohort of 24 RA patients took a mean of 8 months and began with a naïve population that eventually matured. Relapses were noted to correlate with increased numbers of mature B-cells in the peripheral blood.

Of substantial relevance to the pediatric patient population, in which the RF-positive population comprises approximately 10% of children with polyarticular arthritis (CitationKrumrey-Langkammerer and Hafner 2001), two of the trials compared the effectiveness of rituximab therapy in the RF-positive and RF-negative patient populations. One found that the drug was equally effective in both populations, while the other found that there were no differences between RF-negative placebo patients compared with RF-negative study drug patients, although the placebo patients in this study had an unusually high response rate, complicating interpretation of the data (CitationCohen et al 2006; CitationEmery et al 2006).

To our knowledge, there are only three case reports of rituxumab use in JIA patients, one of whom was an adult at the time of the study. CitationKuek and colleagues (2006) administered rituximab to a 26-year-old woman with RF-negative polyarticular JIA of 18 years duration, reporting improvements in her functional status and tapering of concomitant corticosteroid therapy (CitationKuek et al 2006). CitationEl-Hallak and colleagues (2007) reported on experiences in 10 children from a single center with various autoimmune conditions treated with rituximab with the lymphoma protocol of 375 mg/m2 weekly x four weeks, one of whom had polyarticular JIA; her rheumatoid factor status was not reported. This patient did respond well to the therapy (CitationEl-Hallak et al 2007). Finally, CitationDass and colleagues (2007) reported on three patients who developed psoriasis following rituximab use, one of whom was a 17-year-old girl with long-standing B27+, RF-poly-arthritis, who had an unsatisfactory response for six months, before developing psoriasis, pan-uveitis, and Achilles tendon rupture (CitationDass et al 2007).

Safety

Most of the safety data for rituximab comes from its use in lymphoma, since over 700,000 patients have received this therapy (CitationSolal-Celigny 2006). The most common side effects are infusion reactions, which are typically mild and tend to resolve after the first dose, although they rarely can be quite severe, resulting in hypotension, bronchospasm, and occasionally even death (CitationKimby 2005; CitationMohrbacher 2005). Cases of serum sickness, transient cytopenias, and tumor lysis syndrome have also been reported, although the latter is unique to its use in lymphoma (CitationTodd and Helfgott 2007). With respect to infections, the overall oncology experience has been that treated patients have not had more severe or opportunistic infections than would otherwise be expected, given the population, although reactivation of Hepatitis B has been reported (CitationTsutsumi et al 2005; CitationSolal-Celigny 2006).

None of the three randomized, controlled trials in RA demonstrated a statistically significant increased infection risks, although one did demonstrate a nonsignificant increased risk; none of the studies reported cases of tuberculosis or opportunistic infections (CitationEdwards et al 2004; CitationCohen et al 2006; CitationEmery et al 2006). Likewise, data from observational studies in adults with RA has generally been reassuring, with mild infusion reactions being the most commonly reported adverse event (CitationLeandro et al 2002; CitationKneitz et al 2004; CitationMoore et al 2004; CitationGottenberg et al 2005; CitationHigashida et al 2005; CitationBrulhart et al 2006; CitationFinckh et al 2007; CitationJois et al 2007; CitationPopa et al 2007). When serious infections have occurred, it was generally unclear whether they were related to the study drug, with the exception that one patient in the study by CitationPopa and colleagues (2007) did develop hypogammaglobulinemia and respiratory infections associated with bronchiectasis. Recently, CitationDass and colleagues (2007) published a case report of three patients who developed psoriasis during rituximab use. They were a 17-year-old B27-positive, RF-negative JIA patient, a 52-year-old woman with RF-positive RA, and a 26-year-old lupus patient (CitationDass et al 2007).

As noted above, there is limited published use of this therapy in children with arthritis. There is, however, pediatric data from oncological uses, as well as in other autoimmune diseases, including idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and pediatric lupus. Most of these studies have demonstrated safety and effectiveness, with major side effects being infusion reactions and in some cases, serum sickness (CitationQuartier et al 2001; CitationMarks et al 2005; CitationWang et al 2005; CitationBennett et al 2006; CitationParodi et al 2006; CitationEl-Hallak et al 2007; CitationRao et al 2007). Interestingly, serum sickness has not been reported much in RA patients, although CitationTodd and Helfgott (2007) speculated that this may be due to under-reporting caused by confusion with arthritis symptoms. One exception to the generally benign experience with rituximab in pediatric patients was the retrospective study by CitationWillems and colleagues (2006), who reported that of 11 pediatric SLE patients treated with rituximab, 5 had severe adverse events, including two with septicemia and four with significant cytopenias.

Finally, the FDA recently issued an advisory warning about two patients with lupus who developed fatal infection with JC virus, the etiologic agent of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) (2007); there have also been several case reports of PML occurring in oncology patients treated with rituximab, all of whom were also treated with other cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents (CitationGoldberg et al 2002; CitationMatteucci et al 2002; CitationSteurer et al 2003; CitationFreim Wahl et al 2007). Details of the co-therapies used by the two lupus patients were not released by the FDA.

Summary

Rituximab is developing a strong effectiveness record in RA, and has been safely used in a variety of other pediatric and adult rheumatological conditions (CitationQuartier et al 2001; CitationMarks et al 2005; CitationPijpe et al 2005; CitationWang et al 2005; CitationBennett et al 2006; CitationParodi et al 2006; CitationScheinberg et al 2006; CitationEl-Hallak et al 2007; CitationRao et al 2007; CitationTanaka et al 2007). A consensus statement released in 2007 recommended use in RF-positive patients who failed TNF inhibitor therapy and who do not have a history of chronic infections. This statement also advised pre-medication with methyl-prednisolone and concomitant use of methotrexate (CitationSmolen et al 2007). However, pediatric data is limited to case reports. Although RA trial data can arguably be extrapolated to RF-positive polyarticular JIA patients, the role of rituximab in RF-negative RA has not been well-defined, and there is minimal data in the spondyloarthropathies. In addition, although rituximab is generally well tolerated, it bears repeating that there have been rare reports of life-threatening infusion reactions and fatal viral infections such as PML (CitationGoldberg et al 2002; CitationSteurer et al 2003; CitationKimby 2005; 2007; CitationFreim Wahl et al 2007).

Abatacept

Basic scientific rationale

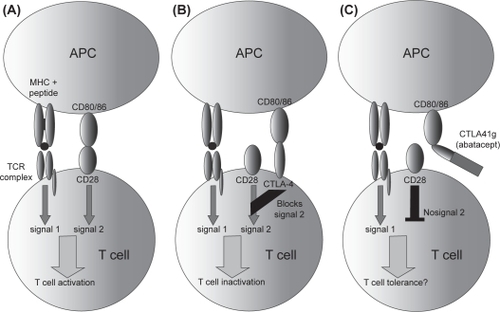

The concept behind abatacept was triggered by basic science knowledge of mechanisms involved in T-cell activation. As reviewed by CitationSalomon and Bluestone (2001), T-cell activation generally requires two specific events: the first is presentation of the peptide-MHC complex to the T-cell receptor; the second is co-stimulation through any number of surface receptors present on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and T-cells, perhaps most importantly the CD80/CD86 on APCs and CD28 on T-cells (CitationSalomon and Bluestone 2001). Cytotoxic T-cell Lymphocyte Antigen-4 (CTLA4) bears structural similarity to CD28, but has much higher affinity for CD80 and CD86 (CitationBluestone et al 2006). CitationLinsley and colleagues (1991) designed a molecule consisting of CTLA4 fused to a modified human Fc region, showing that it inhibited in vitro immune responses; this fusion protein, initially known as CTLA4-Ig, has since been named abatacept (). Abatacept was initially studied in transplant rejection, and its initial clinical application was in psoriasis, but it has largely been used in RA, for which purpose it was approved by the FDA in 2005 (CitationAbrams et al 1999; CitationBluestone et al 2006). Recently, abatacept was also approved for use in polyarticular JIA.

Figure 3 Mechanism of action of abatacept. Under normal circumstances, CD80/86 on antigen-presenting cells (APC) binds to CD28 on T-cells, providing a second signal resulting in T-cell activation following peptide / MHC recognition by the T-cell receptor (A). CTLA4, another receptor on the surface of T-cells, binds to CD80/86 with increased affinity, transmitting negative signals to the T-cell (B). Soluble CTLA4-Ig (abatacept) binds to CD80/86, preventing it from binding to CD28 (C). Copright © 2007 Blackwell Publishing. Reproduced with permission from Todd DJ, Costenbader KH, Weinblatt MT. 2007. Abatacept in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Clin Prac, 61:494–500.

Effectiveness

Abatacept has been studied in five randomized, placebo-controlled trials in RA (CitationMoreland et al 2002; CitationKremer et al 2003, Citation2005, Citation2006; CitationGenovese et al 2005). In three of the studies, participants were required to use methotrexate as co-therapy (CitationKremer et al 2003, Citation2005, Citation2006); in one trial, patients were required to take any oral DMARD or anakinra as concomitant therapy (CitationGenovese et al 2005), and in one, DMARD therapy was not permitted (CitationMoreland et al 2002). Abatacept was effective in all of the trials, more so at 10 mg/kg than 2 mg/kg; dosing was at day 1 and 15, then monthly (CitationMoreland et al 2002; CitationKremer et al 2003, 2005, 2006; CitationGenovese et al 2005).

Results of an open-label trial in JIA were presented at the 2006 ACR conference, but have not yet been published. In this study, 190 children with JIA were treated with abatacept 10 mg/kg IV on days 1, 15, and monthly for four months. 123 of the 190 children (65%) demonstrated ACR-30 responses, and the mean percent reduction in the number of active joints from baseline was 56%. 20 withdrew from the study, 17 for lack of efficacy, one for adverse events, one for withdrawal of consent, and one for undisclosed reasons (CitationLovell et al 2006c). Safety data presented in the following year revealed one case of leukemia diagnosed at day 89 of the open-label phase, which the study investigators suspect may have been present prior to enrollment, and a case of varicella encephalitis in a placebo-treated patient in the double-blind phase of the study (CitationLovell et al 2007).

Safety

Abatacept has generally been well-tolerated. In three of the trials, severe adverse effects were more common in the placebo arms than in the 10 mg/kg abatacept arm, generally related to increased disease flares (CitationMoreland et al 2002; CitationKremer et al 2003, Citation2005); only one study reported increased severe infections in the abatacept arm, a nonsignificant difference of 3.9% vs. 2.3% (CitationKremer et al 2006). There were no reported cases of tuberculosis or opportunistic infections among patients taking abatacept. In addition, as noted above, preliminary data indicates that abatacept was well-tolerated in JIA patients, although these results have yet to be published (CitationLovell et al 2007). Abatacept was also well tolerated in an open-label psoriasis study, with no serious infections or other serious adverse events, aside from hospitalization for an asthma flare in a patient with pre-existing asthma (CitationAbrams et al 1999). To our knowledge, there are no published reports of adverse reactions to abatacept, beyond those detailed in the published trials.

Summary

Abatacept represents a successful transition from basic science research to clinical applications. It appears to be safe and effective in RA, showing success even in patients refractory to TNF inhibitors (CitationGenovese et al 2005). Preliminary data likewise reveals effectiveness in JIA (CitationLovell et al 2006c). One theoretical concern with abatacept is that CTLA4 transmits negative signals to T-cells, so it could potentially have a pro-inflammatory effect, particularly late in the immune reactions, when negative signaling through CTLA4 dominates (CitationBluestone et al 2006). Although this theoretical concern has not been borne out by the clinical data, overall experience, particularly in pediatrics, is limited.

Tocilizumab

Basic scientific rationale

There is data implicating interleukin-6 (IL-6) in the pathogenesis of RA, with particular genetic polymorphisms conferring an increased risk of the disease and elevated serum levels correlating with disease activity (Citationde Benedetti et al 1991; CitationRooney et al 1995; CitationFishman et al 1998; CitationOgilvie et al 2003). CitationSato and colleagues (1993) constructed a partially humanized monoclonal antibody against the IL-6 receptor, by fusing human IgG1 with a murine CDR directed against the receptor for the human cytokine. This antibody, initially called MRA, is now known as tocilizumab. It has not been approved by the FDA and is generally available in the United States for research purposes only.

Effectiveness

There have been five randomized, placebo-controlled trials of tocilizumab in RA, with all five showing effectiveness at doses from 4–8 mg/kg, and lesser effects at lower doses (CitationChoy et al 2002; CitationNishimoto et al 2004, Citation2007; CitationMaini et al 2006; CitationSmolen et al 2008). In one trial, methotrexate did not demonstrate an additive effect at the therapeutic doses of tocilizumab (CitationMaini et al 2006).

In pediatrics, tocilizumab has largely been studied in SOJIA patients; two open-label studies have been published (CitationWoo et al 2005; CitationYokota et al 2005). In the study by CitationWoo and colleagues (2005), 18 children with methotrexate-refractory disease for at least 3 months received tocilizumab at doses of 2 mg/kg, 4 mg/kg, or 8mg/kg; follow-up periods were, respectively, 4, 6, or 8 weeks. The efficacy analysis was only based upon 15 children, as there were unspecified protocol violations in three. Overall, treatment led to improvements in clinical and laboratory features, albeit less so at the 2 mg/kg dose. However, three children required corticosteroid rescue therapy during this short trial, one each at each of the three dosages (CitationWoo et al 2005).

CitationYokota and colleagues (2005) enrolled 11 children age 2–19 into a dose-escalating trial, in which children received three doses of tocilizumab 2 mg/kg every two weeks, with the dose increased stepwise to 4 mg/kg and again to 8 mg/kg if the lower doses failed to maintain CRP levels below 1.5 mg/dL. Treatment was effective, leading to improvements in multiple parameters, including synovitis, markers of inflammation, fever fluctuations, hemoglobin, and platelet count. Three of the 11 children had the disease stabilized based upon CRP measurements at the 2 mg/kg dose, five required the 4 mg/kg dose, and the remainder three were stabilized at the highest dose; all three children who received the 8 mg/kg dose had ACR-70 responses. No children required rescue therapy (CitationYokota et al 2005).

Results from a phase III clinical trial in SOJIA were recently published. In this study, 56 children with SOJIA were treated with tocilizumab open-label at 8 mg/kg every other week for six weeks. 43 met responder criteria and were enrolled into the 12-week long double-blind withdrawal phase; 83% of placebo patients compared with 20% of tocilizumab-treated patients withdrew from the study (CitationYokota et al 2008). An additional study presented at the 2006 ACR conference evaluated the safety and efficacy of tocilizumab in a 12-week long open-label trial of 19 children with polyarticular JIA, showing improvement in clinical parameters; however, of the 19 children, three were hospitalized: two for gastroenteritis and one for sensory disturbance (CitationImagawa et al 2006).

Safety

In the open-label pediatric trial published by CitationWoo and colleagues (2005), multiple adverse events were reported: there were 9 infections in total, although the only ones that were considered serious were chicken pox and herpes simplex oral ulcerations. Other serious adverse events were disease flares in two patients and transient pancytopenia in one. In addition, lymphopenia was noted in 15 of 18 patients and transient increases in liver function tests were noted in three (CitationWoo et al 2005). In contrast, in the study by CitationYokota and colleagues (2005), therapy was well-tolerated, without any serious adverse events; the only potentially infectious adverse events over the 80 days of follow-up were URIs in two children and pustules on the extremities of three. No cytopenias or any other major laboratory abnormalities were reported (CitationYokota et al 2005). In the phase III study in SOJIA, safety analysis revealed two serious adverse events during the open-label lead in phase, consisting of one anaphylactic reaction and one case of gastrointestinal hemorrhage; two serious adverse events during the double-blind phase, consisting of an EBV infection associated with marked increases in transaminases in a tocilizumab-treated patient and a case of Zoster in a placebo patient; and 13 serious adverse events in an open-label extension phase lasting 48 weeks and enrolling 50 children. Most of these did not appear to be life-threatening, with the exception of an anyphylactic reaction that led to drug discontinuation (CitationYokota et al 2008). Finally, in the trial of tocilizumab in polyarticular-JIA, three of 19 children were hospitalized over 12 weeks (CitationImagawa et al 2006). There is a case report of the sudden onset of fatal congestive heart failure and interstitial pneumonitis in a patient with severe chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, and articular (CINCA) syndrome who had responded well to tocilizumab for two months prior to his rapid demise; despite the sudden onset of the symptoms, the authors excluded the possibility of an infection causing the patient’s deterioration (CitationMatsubara et al 2006).

Likewise, therapy has generally been tolerated in the adult RA patients, although three of the five studies showed nonstatistically significant increases in serious infections in the drug arm (CitationNishimoto et al 2004, Citation2007; CitationMaini et al 2006), while another did not present detailed analysis of the serious infections (CitationChoy et al 2002). There was one reported death, secondary to Epstein-Barr virus reactivation, in the tocilizumab arm of one of the studies (CitationNishimoto et al 2004).

Summary

Tocilizumab may have an important role in both RA and SOJIA (CitationChoy et al 2002; CitationNishimoto et al 2004, Citation2007; CitationWoo et al 2005; CitationYokota et al 2005, Citation2008; CitationMaini et al 2006; CitationSmolen et al 2008); its role in other subtypes of JIA is undetermined. With respect to safety, several randomized controlled trials in RA have shown increases in serious infections in the tocilizumab groups, with one reported death (CitationNishimoto et al 2004, Citation2007; CitationMaini et al 2006); importantly, all of these trials were dose-ranging and therefore had more patients in the tocilizumab arms, but this is clearly an issue that bears further monitoring. In the SOJIA trials, small numbers of enrolled patients preclude definitive conclusions, although occurrences of lymphopenia in one of the trials, as well as three hospitalizations over 12 weeks in another, do suggest a need for caution (CitationWoo et al 2005; CitationImagawa et al 2006), as does the sudden onset of interstitial pneumonia and congestive heart failure in a CINCA patient whose disease had been brought under good control with therapy (CitationMatsubara et al 2006). Finally, as noted above, tocilicumab has not been approved by the FDA, so would only be available in the United States on an experimental basis.

Combination biological therapy

Theoretically, there may exist a sound rationale for combining therapy with inhibitors of TNF and other biologics, such as anakinra. The complexity of the cytokine and intracellular signaling pathways makes it unlikely that a single biologic, targeting a single cytokine or cell surface receptor, will be uniformly or completely effective, and indeed, success is measured in improved responses, not complete remission (CitationIsaacs et al 1999; Citationvan den Berg 2002). In several different animal models of arthritis, combination therapy with infliximab and anakinra has been significantly more effective than mono-therapy with either agent (CitationBendele et al 2000; CitationFeige et al 2000; CitationZwerina et al 2004). Therefore, the possibilities of combination therapy have attracted clinical interest; unfortunately, data to date has not been rewarding.

To our knowledge, CitationGenovese and colleagues (2004) was the first to formally evaluate combination therapy in humans. In this study, 242 adult RA patients previously untreated with TNF inhibitors or anakinra were randomized to receive etanercept + anakinra placebo, etanercept + anakinra, and half-dose etanercept (25 mg weekly) + anakinra. After 24 weeks, the three groups had generally equivalent responses, with the full-dose etanercept arm actually showing a higher ACR20 response than the etanercept–anakinra combination arm. However, safety analysis revealed significant differences, with both combination arms being associated with significantly increased incidences of serious adverse events and events leading to withdrawal. For example, serious infections were reported in 0/80 etanercept controls, compared with 3/81 half-dosage etanercept – anakinra combination patients and 6/81 full-dosage etanercept – anakinra combination patients; there was one death in the full-dosage combination arm: respiratory insufficiency triggered by pneumonia in a patient with pre-existing pulmonary fibrosis (CitationGenovese et al 2004).

Two recent studies have evaluated combination therapy involving abatacept. CitationWeinblatt and colleagues (2006) randomized 1441 RA patients to abatacept or placebo. An important and unique aspect of this trial is that some of the patients in each group were on background biologic therapy while others were not, thus permitting analysis of the safety of abatacept with or without background biologic therapy. Overall, the abatacept and placebo arms were similar with respect to overall adverse events, serious adverse events, and discontinuations, with a small but statistically nonsignificant increase in serious infections in the patients receiving abatacept (2.6% vs. 1.7%). However, in the subgroup of patients on background biologic therapy, serious infections were reported in 6/103 (5.8%) of abatacept-treated patients, vs. 1/64 (1.6%) control patients. Post-hoc efficacy analysis was performed in this safety trial; no evidence of an additive effect was demonstrated (CitationWeinblatt et al 2006).

Finally, CitationWeinblatt and colleagues (2007) randomized 121 patients with an incomplete response to etanercept to receive abatacept or placebo on top of pre-existing etanercept therapy. The abatacept dose in this study was 2 mg/kg on days 1, 15, and 30 followed by every four weeks for a total of six months, at which point the dose was increased to 10 mg/kg for another six months. Overall, there were minimal differences in effectiveness between the groups, although the abatacept 2 mg/kg arm did have an increased ACR-70 response at six months. However, at 12 months, the abatacept-treated patients also showed significantly higher serious adverse events, serious infections, and withdrawals due to adverse events (CitationWeinblatt et al 2007).