Abstract

The purpose of this study was to compare chemotherapy-naive patients with stage IV nonsmall cell lung cancer patients treated with chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy. We tested doxetacel plus cisplatinum as chemotherapy protocol. An immunomodulatory adjuvant system was added as chemoimmunotherapy to the previously mentioned protocol. This system contains three well-known and complementary conditioners of protective immune-responses: cyclophosphamide low-dose, granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulant factor and magnesium silicate granuloma. Eighty-eight patients were randomly assigned to receive every 3-weeks one of the treatments under comparison. Patients received four cycles of treatment unless disease progression or unacceptable toxicity was documented. The maximum follow-up was one year. In each arm, tumor response (rate,duration), median survival time, 1-year overall survival, safety, and immunity modifications were assessed. Immunity was evaluated by submitting peripheral blood mononuclear cells to laboratory tests for nonspecific immunity: a) phytohemaglutinin-induced lymphocyte proliferation, b) prevalence of T-Regulatory (CD4+CD25+) cells and for specific immunity: a) lymphocyte proliferation induced by tumor-associated antigens (TAA) contained in a previously described autologous thermostable hemoderivative. The difference (chemotherapy vs. chemoimmunotherapy) in response rate induced by the two treatments (39.0% and 35.0%) was not statistically significant. However, the response duration (22 and 31 weeks), the median survival time (32 and 44 weeks) and 1-year survival (33.3% and 39.1%) were statistically higher with chemoimmunotherapy. No difference in toxicity between both arms was demonstrated. A switch in the laboratory immunity profile, nonspecific and specific, was associated with the chemoimmunotherapy treatment: increase of proliferative lymphocyte response, decrease of tolerogenic T-regulatory cells and eliciting TAA-sensitization.

Introduction

Despite aggressive treatment with surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality, resulting in more than 160,000 deaths per year in the United States and 1.2 million worldwide. Nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 80% of all lung cancers (CitationALA 2005).

The treatment of advanced stages of lung cancer with systemic chemotherapy has obtained modest results (CitationSocinski et al 2003). Immunotherapy, another systemic treatment, also has been disappointing since the historic intents with BCG (bacille Calmette Guérin; Hadźiev et al 1982), Corynebacterium parvum (CitationIssell et al 1978), and thymosin (CitationChretien et al 1979) up to the recent trials with humanized antibodies targeting specific tumor-associated antigens (CitationLynch et al 2004). However, in last years, new platforms for chemotherapy as tumor antigens releaser and immunotherapy as immunomodulatory conditioner have introduced a rational for the association of these platforms in a chemoimmunotherapy protocol in order to improve the results of advanced NSCLC treatment.

In fact, chemotherapy is a tumor antigens releaser. In malignant disease spontaneously progressing, without treatment, the content of dying tumor cells is transferred to the interstice, to the lymph and to the blood. Some components of that content are tumor-associated antigens (TAA). This malignant tumor content, released from dying cells, meets the immune system in the interstice, in the lymph, and also in the circulating blood. This mechanism can work as a spontaneous endogenous vaccination. However, it is evident the failure of tumor immune control by this spontaneous endogenous vaccination in progressive cancer. This failure could be result of the low antigenicity of TAA released from spontaneous apoptotic tumor cells death (CitationMelcher et al 1998) and the conditioning of tolerogenic or permissive immune response induced during the carcinogenesis (CitationCochran et al 2006). Apoptotic tumor cell death increases when malignant disease is submitted to oncological treatments, mainly chemotherapy. Cell death through apoptosis is less immunogenic than cell death through necrosis (CitationMelcher et al 1999). However, the immunogenicity is maintained when apoptosis follows a cellular stress (CitationFeng et al 2002) as it is produced by chemotherapy (CitationTiligada 2006). Therefore, chemotherapy works, at least partially, as an endogenous vaccination enhancer with high efficacy as releaser of TAA antigens, one of the components in the configuration of cancer vaccines (CitationRaez 2005).

Immunomodulatory conditioning is a new platform of immunotherapy. The goal is to switch the tolerogenic (permissive) tumor-induced conditioning of the immune responses to immunogenic (protective) immune responses (CitationPinedo et al 2000; CitationRini et al 2005). A tool to accomplish this goal is the described systemic depletion of tolerogenic T-regulatory cells population (CD4+CD25+) by cyclophosphamide at low dose, injected a short period (three days) before antigen stimulation (CitationBerd et al 1982; CitationGhiringhelli et al 2004). Another tool is the recently described immunotherapeutic site (ITS), where different immunomodulatory agents are injected in order to induce in the draining lymph node an increase of activated antigen-presenting cells and a depletion of tolerogenic T-regulatory cells. This loco-regional immunomodulation is decisional because it elicits a systemic protective lymph nodes conditioning. Among other agents (erythrocytes or other local inflammatory agents) to create an ITS, magnesium silicate that produces a subcutaneous granuloma (MSG) was reported as a strong inducer of remote macrophage activation with enhancement of protective antitumor immune responses, when it is performed during the 4 days previous to the antigen (CitationFauve and Hevin 1977; CitationFontan et al 1983, Citation1992; CitationFauve et al 1987). It was also reported that granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), injected subcutaneously, simultaneously or around the time of antigen stimulation, is a recruiter and activator of antigen presenting cells, mainly dendritic cells (CitationDisis et al 1996; CitationDranoff 2002).

Briefly, the association of systemic low-dose cyclophosphamide and a locoregional lymph node immunomodulation by MSG and GM-CSF is a safe immunomodulatory adjuvant system (IAS) of cancer vaccines supported by the proven properties of their components and evidenced in previous clinical trials (CitationGarcia-Giralt et al 2006, Citation2007; CitationLasalvia-Prisco et al 2007a, Citation2007b, Citation2007c). This study compared in advanced NSCLC, the antitumoral and immunological effects of the standard chemotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy designed using the same chemotherapy in its platform of tumor antigens releaser and the platform of immunomodulatory conditioning immunotherapy through and IAS with cyclophosphamide, MSG, and GM-CSF.

Patients and methods

Patients and trial

Patients were submitted to a randomized phase II study. The trial accomplished the flow diagram and checklist of the CONSORT statement in conjunction with the CONSORT explanation and elaboration document (CitationAltman et al 2001; CitationMoher et al 2001).

The patient’s characteristics are summarized in . Eighty-eight patients who met the following eligibility criteria were included. The criteria were: histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of inoperable NSCLC (stage IV); age ≤75 years; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (CitationOken et al 1982) ≤2; no prior malignancy, chemotherapy, surgery, or radiotherapy; no central nervous system metastases and at least one measurable lesion; tumor burden comprising no more than 3 metastasis sites; no associated acute disease. Conservation of organic functions was confirmed (adequate bone marrow function: ≥WBC 3000/mm3, ANC ≥1500/mm, Hgb ≥9.0 g/dl, and platelets ≥100,000/mm3; adequate liver function: bilirubin ≤1.5 mg/dl, aspartate aminotransferase ≤40 IU/L; adequate kidney function: creatinine ≤1.5 mg/dl). The study was conducted in patients admitted to medical centers that submitted medical data to the Cooperative Trials Center (CTC) of Interdoctors Medical Procedures, Florida, USA (Interdoctors Medical Procedures is a nonpharmaceutical concern group supporting scientific research in medical procedures). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the trial, which complied with the Declaration of Helsinki (CitationWMA 1997). In a prospective, randomized, controlled trial, the treating physicians did not participate in the arm randomization for their patients. The patients were randomized into 2 groups that received different treatments: chemotherapy (CHT) or chemoimmunotherapy (CHIMT). Basically, CHIMT is CHT with the IAS associated to each chemotherapy series.

Table 1 Patients’ characteristics

Chemotherapy

CHT protocol was one of the therapeutic options recommended in the PDQ (Physician Data Query) database of the National Cancer Institute for Stage IV, NSCLS: doxetacel plus cisplatinum (CitationGeorgoulias et al 2004). Briefly, doxetacel 100 mg/m2 on day 1, and cisplatinum 80 mg/m2 on day 2. The series were repeated every 3 weeks.

Immunomodulative adjuvant system

IAS was added to the study design (CHIMT arm) in each chemotherapy series, considering day 2 as the start day of tumor cell affectation by chemotherapy. Cyclophosphamide 300 mg/m2 was administered on day-1 of each series; GM-CSF 300 μg SC was administrated days 2 to 5, daily, of each series and .a subcutaneous granuloma was induced with 500 mg magnesium silicate on day-2 of each series.

A maximum of 4 series of CHT or CHIMT were programmed.

Assessment

In all patients, data was collected at baseline and followed until death, loss of follow-up, or until a maximum of one year.

Overall tumor response and safety were documented 8 weeks after completion of treatment. The overall response rate was expressed as the proportion of patients demonstrating CR (complete remission) or PR (partial remission) based on all patients randomly assigned to receive treatment and according to the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST). All responses required confirmation at least four weeks after they were first observed (CitationTherasse et al 2000).

Response duration (RD) was calculated from the first date of a 50% reduction in the tumor was registered to the last date that tumor reduction was documented.

At the end of the follow-up (1 year), survival parameters were analyzed for each group using the Kaplan-Meier method from the first day of treatment to death or the date of the last follow-up visit for patients who were still alive. Median time survival (MTS) and one year overall survival (1-OS) were estimated. Assessment of safety was based on reports of adverse events, laboratory-test results, and vital-sign measurements. Adverse events were categorized according to the common toxicity criteria of the National Cancer Institute (CTCAE), version 2 (NCI 2006).

Laboratory tests

The laboratory tests were designed taking in account preliminary assays in patients treated with each component of IAS, showing accumulative increase of peripheral blood monomolecular cells (PBMC) proliferation responses to phytohemaglutinin (PHA) and decrease of T-regulatory cells (results not shown) supporting the use of the associated three IAS components in this study.

In a sample of PBMC, lymphocyte proliferation assay induced with PHA and T-regulatory Cells (CD4+CD25+) prevalence (T-Reg) were assessed as nonspecific immune-reactivity parameters. It was previously demonstrated that an autologous thermostable hemoderivative (ATH) contained TAA (CitationLasalvia-Prisco et al 2003, Citation2006a, Citation2006b); therefore, lymphocytes proliferation assay induced with this ATH was evaluated as specific assay for immunity against circulant TAA.

Isolation of PBMC

Heparinized blood was diluted 1/1 v/v with phosphate buffer solution (PBS) before Ficoll density centrifugation. The buffy coat containing PBMC was harvested, contaminating red blood cells lysed by incubating in ACK-lysing buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4), and washed twice in cold PBS. A PBMC sample in each patient was prepared at days-3, 3 and 20 of the first treatment series.

PHA and ATH lymphocyte proliferation assay

PHA was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). For each test, a fresh ATH was prepared as it was described (CitationLasalvia-Prisco et al 2003).

PHA and ATH lymphocyte proliferation assays were made immediately after obtaining each sample of PBMCs, days-3, 3 and 20 by incubating 105 PBMCs, from an aliquot of PBMC sample obtained as mentioned above, added to 100 μl of RPMI 1640 with 10% human AB serum and deposited in round-bottomed wells on a 96-well plate. Two immunologic challenges and appropriate controls were tested in triplicate: a) Medium control in the top row, an additional 100 μl of working RPMI 1640 medium; b) PHA, 100 μl of a serial dilution of stock PHA (0.5 mg/ml) in RPMI 1640 (1:10, 1:100 and 1:500) was placed in triplicate wells of the first 9 wells of the second row; c) ATH, 100 μl of a serial dilution of ATH (10x concentrate from 20 mL blood) in RPMI 1640 (1:10, 1:100 and 1:500) was placed in triplicate wells of the first 9 wells of the third row; d) Negative control, 100 μl of l:100 dilution of healthy male plasma in RPMI 1640 medium was added to each of first 3 wells of the forth row. RPMI 1640 were also obtained from Sigma. Plates were incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 5 days. One microcurie of tritiated thymidine was then added to each well in a volume of 20 μl and plates were again incubated, at 37 °C for 16 h. The content of each well was harvested and counted in a liquid scintillation beta-counter. The mean of the three determinations per point was registered as mean-cpm of each challenger. The mean-cpm of the negative control was divided by the mean-cpm of the media control. If this ratio was less than 2.00, then the negative control was accepted. For each test in each patient, the mean-cpm of the PHA dilution with the highest cpm was divided by the mean of the media control, expressed as % of the value calculated for the day -3 and defined as PHA lymphocyte proliferation response (PHA-LPR). Also for each test in each patient, the mean-cpm of the ATH dilution with the highest cpm was divided by the mean-cpm of the media control expressed as a percentage of the value calculated for the day -3 and defined as ATH lymphocyte proliferation response (ATH-LPR). The results were statistically compared in both treatment arms.

T-regulatory (CD4+CD25+) prevalence

An aliquot of each PBMC sample, days-3, 3 and 20, isolated from peripheral blood, were used for two and three color cell surface labeling using Abs against CD4 and CD25. We analyzed the cell samples by flow cytometry after cell surface labeling for co-expression of CD4 and CD25 molecules. The prevalence of CD4+CD25+ cells as a percentage of total CD4+ population was determined by standard determination of quadrant statistics and registered as T-regulatory cells value (T-reg). For each test, days-3, 3 and 20, in each patient, T-reg values were expressed as percent of the day -3 mean values and defined as T-reg response (T-regr). The results in both treatment arms were statistically compared.

Statistical analysis

Response rate to treatment (RR), response duration (RD), median survival time (MST), and 1-OS were the primary end-point. Secondary end-points included safety and laboratory tests.

Survival rates at 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated and the comparisons between the two treatment procedures were carried out using the two-tailed log-rank test. The sample size for survival (log-rank) was assessed using the approach of Schoenfeld and Richter. RR in both groups was compared using Fisher’s exact test. RD difference was evaluated using the generalized Wilcoxon test. Results of the laboratory tests (PHA LPR, ATH LPR, and T-regr) in the two arms were statistically compared by unpaired Student’s t-test. Statistical analysis was performed with WINKS Statistical Data Analysis (SDA) software (TexaSoft, Cedar Hill, TX).

Results

Eighty-eight patients who met the eligibility criteria were accrued into the study; 44 patients were randomly assigned to each treatment arm, CHT and CHIMT. Eighty-one patients were assessable, 41 in CHT arm and 40 in CHIMT arm. Seven patients were nonassessable because of unrelated intercurrent diseases (4 patients), refused further treatment after one chemotherapy series (2 patients), and nonaccomplishing follow-up (1 patient).

Patient characteristics are listed in .

The treatment arms, CHT and CHIMT, were balanced with respect to the clinical prognosis parameter, respectively. The median age was 56 and 58 (range 40 to 73 and 33 to 74 years); at least 5% weight loss (48.8% and 55.0%); cell type was squamous cell carcinoma in 15 and 16 patients (36.6% and 40.0%), large cell in 10 and 9 patients (24.4% and 22.5%), adenocarcinoma in 12 and 10 patients (29.3% and 25.0%), and not specified in 4 and 5 patients (10.0% and 12.5%).

shows the analysis of tumor response in both arms.

Table 2 Overall tumor response

RD was 39.0% (1 patient with CR and 15 patients with PR) in CHT arm and 35.0% (14 patients with PR) in CHIMT arm. The difference in response was not statistically significant (p = 0.12).

RD was 22 weeks in CHT arm and 31 weeks in CHIMT arm. This difference was significant (p < 0.05).

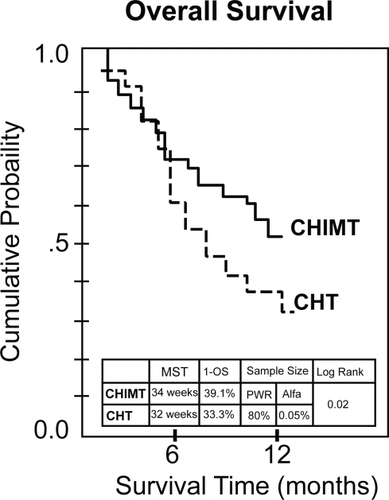

shows the survival parameters in the two treatment arms.

Figure 1 Stage IV nonsmall cell lung cancer at one-year follow-up. Observed survival in the chemotherapy arm (CHT; 41 patients): Doxetacel + cisplatinum and the chemoimmunotherapy arm (CHIMT; 40 patients): CHT + immunomodulatory adjuvant system. Survival rates at 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated and the comparisons between the two treatment procedures were carried out using the two-tailed log-rank test. P-value for log-rank test was calculated. The sample size for Survival (log-rank) was assessed using the approach of Schoenfeld and Richter.

The values of MST and 1-OS: in CHT and CHIMT arms, MSTs were 32 and 44 weeks, respectively; 1-OS were 33.3% and 39.1%, respectively. also shows overall survival curves for the two treatment arms. The log rank test showed a statistical significant difference between the survival curves favorable to CHIMT versus CHT (p = 0.02). The sample size was small but reached a power of 80% for an alpha value of 0.05%.

No different toxicity according CTCAE (NCI 2006) between CHT and CHIMT was evident. The most significant (grade 3/4) toxicities found included, respectively: nausea (7 and 5 cases), hypertension (4 and 3 cases), diarrhea (1 and 2 cases), dyspnea (1 and 0 cases), neurosensory toxicity (3 and 5 cases), hypomagnesaemia (1 and 1 cases), and neutropenia (7 and 5 cases).

shows the PBMC tests results.

Table 3 Immune assessment of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

The mean ± SD of PHA-LPR was significant higher in CHIMT posttreatment samples, day 20, than in CHIMT pretreatment samples, day -3. No significant difference was in evidence in PHA-LPR day 3 and day -3 of CHIMT treatment. No significant difference found in CHT tests.

The mean ± SD of T-regr prevalence was a mirror image of PHA-LPR. It was lower in CHIMT posttreatment samples, day 20, than in CHIMT pretreatment samples, day -3. No significant difference in T-reg day -3 and day 3 of CHIMT treatment was in evidence. No significant difference found in CHT tests.

The mean ± SD of ATH-LPR was also higher in CHIMT posttreatment latest samples, day 20, than in CHIMT pre-treatment samples, day -3. However, there was a small significant difference of higher values in early posttreatments tests, day 3, versus pretreatment tests, day -3 in both, CHT and CHIMT arms. No significant variation was found in late CHT posttreatments tests, day 20.

Discussion

This study of an innovative therapeutic platform reports exhaustively from previous own and independent references supporting the rational of this procedure.

The patients in the two arms were comparable in the considered prognostic parameters (). The sample size was acceptable according to the approach of Schoenfeld and Richter and it also accomplished the criteria recently reported for the two-arm design of phase II clinical trials (CitationTaylor et al 2006). The RRs were statistically nondifferent between CHM and CHIMT and the values are in the range of RR reported in similar medical conditions treated only with comparable chemotherapy (CitationSocinski et al 2003). We infer that the tested immunomodulatory adjuvant had no influence upon the initial response to chemotherapy. Differently, the duration of response and the survival parameters were all statistically increased in CHIMT compared with CHT. This increment is also evident if we compare CHIMT results with the previously reported same parameters in trials of comparable patients treated with comparable chemotherapy (CitationSocinski et al 2003). We deduce that the tested immunomodulatory adjuvant elicits a mechanism that maintains the response to chemotherapy. The statistically significant increase of PHA-LPR and the significant decrease of T-reg are compatible with a switch of the immune system, conditioning the immune responses from the permissive (tolerogenic) to the protective (immunogenic). These facts concur with the reported immunomodulatory activity of the IAS components: Cyclophosphamide, low dose, 3 days before antigen stimulation, decreases the CD4+CD25+ (T-reg) cell population (CitationBerd et al 1982; CitationGhiringhelli et al 2004). The magnesium silicate granuloma has been demonstrated as a remote enhancer of systemic macrophage activity committed to the protective responses (CitationFauve and Hevin 1977; CitationFontan et al 1983, Citation1992; CitationFauve et al 1987). GM-CSF, subcutaneously, administered around the antigenic stimulation, recruits and activates the antigen presenting cells, mainly dendritic cells, allowing a stronger immune response (CitationDisis et al 1996; CitationDranoff 2002).

The influence of this nonspecific immunity modulation upon the specific antitumor immunity is suggested by the results of ATH-LPR. The early increase of ATH-LPR at day 3, in both arms, CHT and CHIMT, is compatible with higher release of TAA induced by chemotherapy and recovered in the contemporary ATH. The most important increase of ATH-LPR, evidenced at day 20, is exclusive of CHIMT and is associated with the immunity nonspecific modulation. We interpret that chemotherapy-induced apoptosis produced an immunogenic TAA release from tumor cells, impacting upon an immune system that could be conditioned by IAS to elicit protective responses, resulting in an immunotherapy mechanism added to the chemotherapy antitumor effect. The antitumor response duration and the survival parameters are higher in CHIMT arm than in CHT arm. This result is compatible with a protracted antitumor effect of chemotherapy plus immunotherapy, which delays the recovery of tumor growth after remission induced by cytotoxic drugs.

Conclusion

CHT and CHIMT resulted in a not-different RR but CHIMT maintained the cancer control safely for a longer period, improving RD, MST, and 1-OS compared with CHT. The immunity-associated changes are compatible with a potentiation of the time-effective chemotherapy-antitumor-effect through an internal vaccination by TAA (released from chemotherapy-induced tumor cells apoptosis) impacting upon a modulated proprotective/antipermissive immune system. Despite the small number of cases of this phase II study, the statistical significance evidenced warrants further investigations in order to assess the clinical relevance of this chemo-immunotherapy.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- AltmanDGSchulzKFMoherD2001The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaborationAnn Intern Med1346639411304107

- [ALA] American Lung Association2005Epidemiology and statistical unit. Research and program services. Trends in lung cancer morbidity and mortality

- BerdDMastrangeloMJEngstromPF1982Augmentation of the human immune response by cyclophosphamideCan Res4248626

- ChretienPBLipsonSDMakuchRW1979Effects of thymosin in vitro in cancer patients and correlation with clinical course after thymosin immunotherapyAnn N Y Acad Sci33213547316979

- CochranAJHuangRRLeeJ2006Tumour-induced immune modulation of sentinel lymph nodesNat Rev Immunol66597016932751

- DisisMLBernhardHShiotaFM1996Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: an effective adjuvant for protein and peptide-based vaccinesBlood88202208704175

- DranoffG2002GM-CSF-based cancer vaccinesImmunol Rev1881475412445288

- FauveRMFontanEHevinMB1987Remote effects of inflammation on non-specific immunityImmunol Lett163–41992033443469

- FauveRMHevinMB1977Inflammation et Résistance AntitumoreAnn Immunol (Inst Pasteur)128C9238

- FengHZengYGranerMW2002Stressed apoptotic tumor cells stimulate dendritic cells and induce specific cytotoxic T cellsBlood (Immunobiology)100410815

- FontanEFauveRMHevinMB1983Immunostimulatory mouse granuloma proteinProc Nat Acad Sci USA80639586578514

- FontanESaklani-JusforguesHFauveRM1992Immunostimulatory human urinary proteinProc Natl Acad Sci USA894358621584770

- Garcia-GiraltELasalvia-PriscoECucchiS2006Ovarian cancer: autologous immunotherapy optimized by remote adjuvancy of a silicate-induced granuloma [abstract]Am Soc Clin Oncol (ASCO)42nd Annual Meeting12515

- Garcia-GiraltELasalvia-PriscoECucchiS2007Breast cancer: draining lymph node of vaccination site targeted by adjuvant GM-CSF in an autologous vaccine [abstract]Am Soc Clin Oncol (ASCO)43rd Annual Meeting13506

- GeorgouliasVArdavanisAAgelidouA2004Doxetacel versus doxetacel plus cisplatin as front-line treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized, multicenter phase III trialJ Clin Oncol222602915226327

- GhiringhelliFLarmonierNSchmittE2004CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress tumor immunity but are sensitive to cyclophosphamide which allows immunotherapy of established tumors to be curativeEur J Immunol343364414768038

- HadźievSMandulovaPKavaklieva-DimitrovaJ1982BCG immu-notherapy of lung cancer in a district oncology dispensary. I. Study of 860 patients with histologic diagnosisNeoplasma29931106280082

- IssellBFValdiviesoMHershEM1978Combination chemoimmunotherapy for extensive non-oat cell lung cancerCancer Treat Rep62105963356968

- Lasalvia-PriscoECucchiSVázquezJ2003Antitumor effect of a vaccination procedure with an autologous hemoderivativeCancer Biol Ther21556012750554

- Lasalvia-PriscoEGarcia-GiraltECucchiS2006aAdvanced colon cancer: antiprogressive immunotherapy using an autologous hemoderivativeMed Oncol239110416645234

- Lasalvia-PriscoEGarcia-GiraltECucchiS2006bAdvanced breast cancer: Antiprogressive immunotherapy using a thermostable autologous hemoderivativeBreast Cancer Res Treat1001496016819567

- Lasalvia-PriscoEGarcia-GiraltECucchiS2007aAdvanced ovarian cancer: Vaccination site draining lymph node as target of immunomodulative adjuvants in autologous cancer vaccineBiologics Targ Ther117381

- Lasalvia-PriscoEGarcia-GiraltECucchiS2007bConditioning of vaccine sentinel lymph node as adjuvant of autologous hemoderivative breast cancer vaccine [abstract]14th European Cancer Conference. Barcelona, 804

- Lasalvia-PriscoEGarcia-GiraltECucchiS2007cProstate cancer: vaccine Sentinel Immunized Node (SIN) target for adjuvant locoregional chemotherapy in autologous vaccine [abstract]Am Soc Clin Oncol (ASCO), 43rd Annual Meeting, 13500

- LynchTJBellDWSordellaR2004Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinibN Engl J Med35021293915118073

- MelcherAGoughMTodrykS1999Apoptosis or necrosis for tumor immunotherapy: What is in a name?J Mol Med778243310682318

- MelcherATodrykSHardwickN1998Tumor immunogenicity is determined by the mechanism of cell death via induction of heat shock protein expressionNat Med458179585232

- MoherDSchulzKFAltmanDG2001The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trialsLancet3571191411323066

- [NCI] National Cancer Institute, US. 2006: Common terminology criteria or adverse events V3.0 (CTCAE).

- OkenMMCreechRHTormeyDC1982Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology GroupAm J Clin Oncol5649557165009

- PinedoHMGruijlTDvan der WallE2000Biological concepts of prolonged neoadjuvant treatment plus GM-CSF in locally advanced tumorsOncologist549750011110601

- RaezLEFeinSPodackER2005Lung cancer immunotherapyClin Med Res3221816303887

- Rini B, Weinberg V, Fong L, et al. 2005. Clinical and immunologic characteristics of patients with serologic progression of prostate cancer achieving long-term disease control with GM-CSF [abstract]. Prostate Cancer Symposium, 261.

- SocinskiMAMorrisDEMastersGA2003Chemotherapeutic management of stage IV non-small cell lung cancerChest123226S43S12527582

- TaylorJMBraunTMLiZ2006Comparing an experimental agent to a standard agent: merits of a one-arm or randomized two-arm Phase II designClin Trials33354817060208

- TherassePArbuckSGEinsenhauerEA2000New guideline to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of CanadaJ Nat Cancer Inst922051610655437

- TiligadaE2006Chemotherapy: induction of stress responsesEndocr Relat Cancer13Suppl 1S11512417259552

- [WMA] World Medical Association. 1997. Declaration of Helsinki: Recommendations guiding medical doctors in biomedical research involving human subjects. Adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, 1964 and as revised in Tokyo, 1975, in Venice, 1983, in Hong Kong, 1989. Version with changes in 1997.