Abstract

Background

Therapy for allergic rhinitis aims to control symptoms and improve the quality of life. The treatment of allergic rhinitis includes allergen avoidance, environmental controls, pharmacologic treatment, and specific immunotherapy.

Objectives

The aim of this study is to evaluate the clinical changes and the levels of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-5 (IL-5) in nasal lavage fluid from children with allergic rhinitis after different types of pharmacologic treatment (mometasone, montelukast, or desloratadine).

Methods

Twenty-four children aged from six to 12 years with moderate persistent allergic rhinitis were randomized into three groups receiving monotherapy treatment over four weeks: nasal corticosteroid (mometasone), leukotriene modifier (montelukast), or antihistamine (desloratadine). The perception of symptom improvement during the medication use was evaluated at the end of the treatment. Samples of nasal lavage fluid were collected before and after treatment for measuring IFN-γ and IL-5 cytokines by ELISA.

Results

All parents perceived an improvement in symptoms. Significant enhancement was seen in the mometasone group compared to those with montelukast (P = 0.01) and desloratadine (P = 0.02). No significant differences were found among the three groups in the levels of IL-5 and IFN-γ in nasal fluid at baseline or after treatment. Only the group treated with mometasone showed a slight but significant reduction in IL-5 levels after the treatment period as compared with levels before the treatment (P = 0.0469).

Conclusion

The group treated with mometasone showed better improvement of clinical symptoms and a slight reduction in IL-5 levels in the nasal fluid. This may indirectly reflect the relative immunomodulatory effects of the drugs tested.

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is currently a global public health problem and is of major importance due to its large increase in world prevalence, ranging from 9% to 42% in the general population and 30% to 40% among children and adolescents.Citation1–Citation3 In Brazil, a previous study using the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) method found a mean rhinitis prevalence of 25.7% in children aged 6 to 7 years, and 29.6% in adolescents aged 13 to 14 years.Citation4 Although AR is a disease with low mortality, its complications such as sinusitis, Eustachian tube dysfunction, sleep disorders, and chronic oral breathing, in addition to its impact on asthma, have resulted in high financial costs.Citation5 In the USA alone, the direct and indirect (drugs, out-patient clinic, school and work absence, and daily activity restriction) annual expenditure is estimated to be around US $1.5 to 2 billion.Citation6 Recent data have indicated that worldwide costs with AR exceed US $5.3 billion per year.Citation7

The management of AR includes allergen avoidance, pharmacotherapy, allergen immunotherapy, and more recently the use of immunomodulators. The goals of the treatment are to relieve symptoms, improve the patient functional capacity, and prevent complications. Classically, treatments could be combined using medications applied topically, systemically, or both. Topical drugs include intranasal corticosteroids, anticholinergics, antihistamines, sympathomimetics, and chromones. Systemic pharmacotherapy includes oral antihistamines, sympathomimetics, antileukotrienes, and particularly in severe cases, corticosteroids. Patients who either react inadequately or experience some side effects of pharmacotherapies are often treated with allergen immunotherapy.Citation8–Citation10

AR is related to an enhancement of Th2 lymphocyte responses, showing increased levels of Th2-profile cytokines, such as interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-13 in nasal mucosa, and a local eosinophilic infiltration, associated with inhibition of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production. These modified responses promote the inflammatory process, which is responsible for the disease symptoms.Citation11

Previous studies using different pharmacotherapies have shown improvement in the symptoms based on clinical scores or questionnaires on health-related quality of life (HRQL); and most of medications such as chromones, topical or oral antihistamines, nasal or oral corticosteroids, and leukotriene antagonists have achieved this objective.Citation12–Citation16 The present study aimed to evaluate the cytokine alterations in nasal lavage fluid from children with AR under different pharmacotherapy interventions (antileukotrienes, intranasal corticosteroids or antihistamines) and the clinical findings in order to investigate the effects of the medications on cytokine levels in the inflammation site and if there are differences between the drugs.

Patients and methods

Subjects

We enrolled subjects aged 6 to 12 years with a history of moderate, persistent AR, requiring pharmacotherapy, in the Ambulatory of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology of the University Hospital of Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Brazil. As inclusion criteria, the subjects should have a positive skin prick test for mite (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae and/or Blomia tropicalis) allergen extracts (ALK-Abelló, Madrid, Spain). A positive skin prick test was established as a wheal exceeding by more than 3 mm in diameter that of the diluents control. The exclusion criteria were as follow: asthma, unless mild and intermittent; the use of intranasal, inhaled, or systemic corticosteroids within 30 days of the study; the use of concomitant medications that could affect the study outcome such as intranasal chromones, intranasal or systemic sympathomimetics, and intranasal or systemic antihistamines, antileukotrienes, or clinically significant nasal disorders such as deviated nasal septum, chronic rhinosinusitis, or nasal obstruction by adenoid hypertrophy; and a history of upper respiratory tract infection within 28 days of the study. The study protocol and the informed consent from parents or legal guardians were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de Uberlandia.

Study design

This was a randomized, open labeled study performed from June 2005 to June 2007. During the first visit, patients were questioned about their clinical history and use of medications, and when compatible, the skin prick test was performed to determine eligibility. A structured questionnaire concerning child age and gender, family and personal history of asthma or atopy, and clinical information was applied. By random draw, 24 patients were divided into three medication groups. Monotherapy was supplied by the researchers over four weeks: montelukast, 5 mg, oral route, once a day; nasal mometasone furoate, 50 μg, once a day; or desloratadine, 5 mg, oral route, once a day.

Symptom evaluation

The perception of improvement during the medication use was evaluated by parents or legal guardians through asking at the end of the four-week treatment. For that evaluation, the parameters were as follows: excellent (very good improvement); good (symptom improvement, although some symptoms persist); regular (small symptom improvement); and bad (no symptom improvement or symptoms worsened).Citation14

Nasal lavage fluid

The nasal lavage fluid was collected from each patient before and after the treatment as described previously.Citation17 Briefly, the patient was maintained with a ±30 degree head extension and the rhinopharynx was occluded by the soft palate. A volume of approximately 5.5 ml of saline solution was instilled into each nostril and after 10 seconds the material was collected, by flexion of the head, into a sterile conic tube, which was immediately maintained in ice, homogenized by agitation, and centrifuged at 1000 × for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and stored at −70 °C until subsequent analysis.

Serum eosinophils and total serum IgE

Before treatment, while collection of the nasal fluid was being performed, blood samples were collected from each patient for eosinophil counts by an electronic counter (Cell Dyn 3.500; Abbott Diagnostic, Abbott Park, IL, USA) and for measurement of total serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) by chemiluminescence (IMMULITE 2000_Total IgE; Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA, USA). Both analyses were performed in the Central Laboratory of Clinical Analyses at the University Hospital and were used to compare the groups.

Measurement of cytokines in nasal lavage fluid

The measurement of IL-5 and IFN-γ cytokines in nasal lavage fluid samples was performed by ELISA according to manufacturer recommendation (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The detection limits of the assays were 7.8 pg/ml for IL-5 and 11.7 pg/ml for IFN-γ.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Nonparametric tests were performed: the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare unpaired samples between the groups and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for analysis of paired samples before and after the treatment within the groups. For comparison between proportions, Fisher’s exact test was used. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

From the 24 patients initially selected for the study, five children were excluded during the treatment due to the use of nonconsented medication according to the exclusion criteria (four children) or withdrawal from the study (one child). Nineteen patients completed the study, with five children in the montelukast group, seven in the mometasone group, and seven in the desloratadine group. shows the demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of patients with AR before treatment in each group. There were no significant differences between the analyzed groups with respect to age, family history of allergy and asthma, associated allergic diseases, total serum IgE levels, and eosinophil counts.

Table 1 Demographic, clinical, and laboratory features of patients with allergic rhinitis before treatment. There are no significant difference among groups (ANOVA for age, Fisher’s exact test for sex and allergy history, and Kruskal–Wallis test for serum IgE and eosinophils)

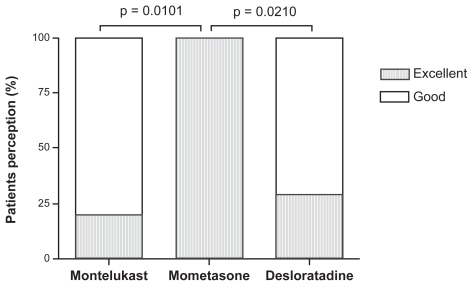

During the treatment period, all parents perceived an improvement in symptoms and considered the therapy excellent or good (). The group treated with mometasone showed a significant improvement in relation to the montelukast group (P = 0.0101) and to the desloratadine group (P = 0.0210). There were no differences between the montelukast and the desloratadine groups ().

Figure 1 Parents’ symptoms perception after treatment with montelukast, mometasone, or desloratadine. All parents related excellent (black bars) or good (white bars) improvement.

*P = 0.0101, **P = 0.0210.

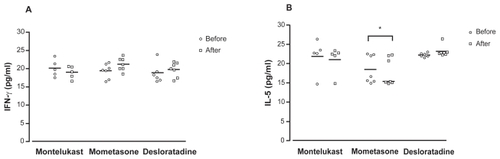

Figure 2 IFN-γ (A) and IL-5 (B) levels in nasal lavage fluid from patients with allergic rhinitis before (circles) and after (squares) the treatment with montelukast, mometasone, or desloratadine. There are no differences among groups by Kruskal–Wallis test.

*Significant differences before and after treatment by Wilcoxon test (P < 0.05).

Levels of IL-5 in nasal lavage fluid before and after treatment in each group are demonstrated in . No significant differences were found among the three groups at baseline and after treatment. When analyzing cytokine changes in each group, median IL-5 levels showed a slight but significant reduction after the treatment with nasal mometasone compared with levels before the treatment (P = 0.0469). There were no differences in IL-5 levels before and after treatment in the montelukast or desloratadine group, although the desloratadine group showed a slight augment in IL-5 levels.

Levels of IFN-γ in nasal lavage fluid samples before and after treatment in each group are demonstrated in . The intergroup analysis did not show significant differences between the groups before and after treatment. Also, median levels of IFN-γ in nasal fluid were not significantly different at baseline and after treatment in each group.

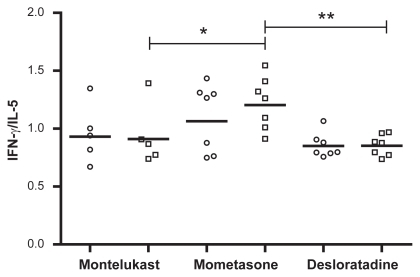

The ratio between IFN-γ/IL-5 did not show differences among the groups before treatment, but after the treatment a significant difference was found between the mometasone and montelukast groups (P = 0.048) and between the mometasone and desloratadine groups (P = 0.0023) ().

Figure 3 IFN-γ/IL-5 ratio in nasal lavage fluid from patients with allergic rhinitis before (circles) and after (squares) the treatment with montelukast, mometasone, or desloratadine. There are no differences among groups before treatment. After treatment there were significant differences between montelukast and mometasone groups (*P = 0.048) and between mometasone and desloratadine groups (**P = 0.023) by Kruskal–Wallis test.

Discussion

Concerning the clinical aspects, despite the fact that patients of all groups in this study showed improvement in symptoms based on the parents’ perception, demonstrating the benefits of treatment, nasal mometasone was slightly superior to other medications, reinforcing recent data that consider nasal corticosteroids as gold standard in the treatment of persistent AR.Citation18–Citation20 In extended trials, the HRQL questionnaires have been used to analyze the clinical response to medications in AR.Citation21,Citation22

Regarding the cytokine changes in nasal lavage fluid, there are few studies on cytokine alteration in nasal fluid in patients with persistent AR. Most of them were performed with seasonal AR or after allergen challenge. The present study showed significant reduction in levels of IL-5 (Th2-profile cytokine) and significant augmention in the ratio IFN-γ (Th1-profile cytokine)/IL-5 in the inflammation site was observed only in the group of patients treated with mometasone. Similar result was found in adults with persistent AR treated with budesonide intranasal after two weeks of medication with reduction in IL-4, IL-5, and IL-6.Citation23 Additionally, two studies found an inhibition of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in nasal secretion following allergen challenge in use of budesonide (two weeks) or fluticasone (a single dose).Citation24,Citation25 Other studies showed a reduced Th2 profile in nasal mucosal biopsies in patients with AR reducing cells that produce IL-4 or in nasal fluid, with reduction of eosinophils and their products.Citation26,Citation27

Montelukast treatment also revealed a decline in IL-5 levels in nasal lavage fluid, but with no significant difference. A previous study reported a significant reduction in levels of IL-4 and IL-13 in nasal lavage fluid after the montelukast treatment of patients with AR and exercise-induced asthma.Citation28 Unlike other groups, an increase in IL-5 levels was found in nasal lavage fluid from patients treated with desloratadine. Other previous studies had shown significant reduction in levels of IL-4 in nasal lavage fluid using desloratadine, levocetirizine, and azelastine.Citation29.Citation30

The findings of the present study contributes information on cytokine profile in inflammation sites and the cytokine changes after treatment with different drugs, which may indirectly reflect the immunomodulatory effects of the drugs tested. Subsequent studies are required to better understand the cytokine profile in the inflamed nasal mucosa and the response to pharmacotherapies.

Disclosures

Financial support was received from CNPQ (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) and FAPEMIG (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais). This study was approved by the Institutional Board Review and Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de Uberlandia. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BousquetJVan CauwenbergePKhaltaevNAria Workshop Group. World Health OrganizationAllergic rhinitis and its impact on asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2001108S147S33411707753

- SettipaneRJHagyGWSettipaneGALong-term risk factors for developing asthma and allergic rhinitis: a 23-year follow-up study of college studentsAllergy Proc19941521258005452

- SkonerDPAllergic rhinitis: definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, detection, and diagnosisJ Allergy Clin Immunol2001108S2S811449200

- SoléDWandalsenGFCamelo-NunesICNaspitzCKISAAC – Brazilian GroupPrevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, and atopic eczema among Brazilian children and adolescents identified by International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISSAC) – Fase 3J Pediatr (Rio J)20068234134616951799

- MeltzerEOQuality of life in adults and children with allergic rhinitisJ Allergy Clin Immunol2001108S45S5311449206

- FinemanSMThe burden of allergic rhinitis: beyond dollars and centsAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol200288S2S7

- SchoenwetterWFDupclayLJrAppajosyulaSBottemanMFPashosCLEconomic impact and quality-of-life burden of allergic rhinitisCurr Med Res Opin20042030531715025839

- Platts-MillsTAVaughanJWCarterMCWoodfolkJAThe role of intervention in established allergy: avoidance of indoor allergens in the treatment of chronic allergic diseaseJ Allergy Clin Immunol200010678780411080699

- BousquetJCauwenbergePKhaledNAPharmacologic and anti-IgE of allergic rhinitis ARIA update (in collaboration with GA2LEN)Allergy2006611086109616918512

- OwnbyDAllergy testing: in vivo versus in vitroPediatr Clin North Am1988399510093050840

- BousquetJKhaltaevNCruzAAAllergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA(2)LEN and AllerGen)Allergy200863Suppl 86816018331513

- Peters-GoldenMHendersonJRThe role of leukotrienes in allergic rhinitisAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol20059460961815984591

- OliveiraCABragaCRSoleDNaspitzCKIntranasal azelastine in the treatment of perennial allergic rhinitis in childrenJ Pediatr (Rio J)19967239439914688906

- TworekDBochenska-MarciniakMKupczykMGorskiPKunaPThe effect of 4 weeks treatment with desloratadine (5 mg daily) on levels of interleukin (IL)- 4, IL-10, IL-18 and TGF beta in patients suffering from seasonal allergic rhinitisPulm Pharmacol Ther20072024424916530440

- CiebiadaMGorska-CiebiadaMDuBuskeLMGorskiPMontelukast with desloratadine or levocetirizine for the treatment of persistent allergic rhinitisAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol20069766467117165277

- VirchowJCBachertCEfficacy and safety of montelukast in adults with asthma and allergic rhinitisRespir Med20061001952195916626955

- KovalhukLCRosarioNACarvalhoAInflammatory mediators, cell counts in nasal lavage and computed tomography of the paranasal sinuses in atopic childrenJ Pediatr (Rio J)20017727127814647858

- RizzoMCSoleDInhaled corticosteroids in the treatment of respiratory allergy: safety vs efficacyJ Pediatr (Rio J)200682S198S20517136296

- ZittMKosoglouTHubbellJMometasona furoate nasal spray: a review of safety and systemic effectsDrugs Saf200730317326

- DerendorfHMeltzerEOMolecular and clinical pharmacology of intranasal corticosteroids: clinical and therapeutic implicationsAllergy2008631292130018782107

- ValeroAAlonsoJAnteparaIDevelopment and validation of a new Spanish instrument to measure health-related quality of life in patients with allergic rhinitis: the ESPRINT questionnaireValue Health20071046647717970929

- PassalacquaGCanonicaGWBaiardiniIRhinitis, rhinosinusitis and quality of life in childrenPediatr Allergy Immunol200718Suppl 18404517767607

- CiprandiGToscaMACirilloIVizzaccaroAThe effect of budesonide on the cytokine pattern in patients with perennial allergic rhinitisAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol20039146747114692430

- ErinEMLeakerBRZacharasiewiczASSingle dose topical corticosteroid inhibits IL-5 and IL-13 in nasal lavage following grass pollen challengeAllergy2005601524152916266385

- ErinEMZacharasiewiczASNicholsonGCTopical corticosteroid inhibits interleukin-4, -5 and -13 in nasal secretions following allergen challengeClin Exp Allergy2005351608161416393327

- BraddingPFeatherIHWilsonSHolgateSTHowarthPHCytokine immunoreactivity in seasonal rhinitis: regulation by a topical corticosteroidAm J Respir Crit Care Med1995151190019067767538

- ParameswaranKFanatAByrnePMEffects of intranasal fluticasone and salmeterol on allergen-induced nasal responsesAllergy20066173173616677243

- CiprandiGFratiFMarcucciFNasal cytokine modulation by montelukast in allergic children: a pilot studyAllerg Immunol (Paris)200335295299

- CiprandiGCirilloIVizzaccaroADesloratadine and levocetirizine improve nasal symptoms, airflow, and allergic inflammation in patients with perennial allergic rhinitis: A pilot studyInt Immunopharmacol200551800180816275616

- SaengpanichSAssanasenPdeTineoMHaneyLNaclerioRMBaroodyFMEffects of intranasal azelastine on the response to nasal allergen challengeLaryngoscope2002112475211802037