Abstract

Background:

It is unknown whether surgery is the gold standard for therapy of thrombosed external hemorrhoids (TEH).

Methods:

A prospective cohort study of 72 adults with TEH was conducted: no surgery, no sitz baths but gentle dry cleaning with smooth toilet paper after defecation. Follow-up information was collected six months after admission by questionnaire.

Results:

Despite our strict conservative management policy 62.5% (45/72) of patients (95% confidence interval [CI]: 51.0–74.0) described themselves as “healed” or “ameliorated”, and 61.1% (44/72, 95% CI: 49.6–72.6) found our management policy as “valuable to test” or “impracticable”. 13.9% (10/72, 95% CI: 5.7–22.1) of patients suspected to have recurrences. 4.2% did not know. Twenty-two of the 48 responding patients reported symptoms such as itching (18.8%), soiling (12.5%), pricking (10.4%), or a sore bottom (8.3%) once a month (59.1%, 13/22), once a week (27.3%, 6/22), or every day (13.6%, 3/22).

Conclusions:

The dictum that surgery is the gold standard for therapy for TEH should be checked by randomized controlled trials.

Introduction

Symptoms of benign anal diseases like internal hemorrhoids rank among the most common complaints of patients seen in primary care practices.Citation1–Citation4 Etiology of thrombosed external hemorrhoid (TEH) is unknown.Citation5–Citation8 Synonyms for thrombosed external hemorrhoid are acute thrombosed external hemorrhoid,Citation8,Citation9 acute hemorrhoidal disease,Citation10 anal hematoma,Citation11,Citation12 perianal hematoma,Citation13,Citation14 thrombosed haemorrhoid,Citation15 hemorrhoidal thrombosis,Citation7,Citation12 or perianal thrombosis.Citation16,Citation17 It was suggested to rename the disease “perianal thrombosis” to make it distinguishable from hemorrhoids since a causal connection is unproven.Citation17 Histologically, thrombi are found in perianal veins, not in subcutaneous tissue andCitation7,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17 the term “hematoma” is wrong.Citation2,Citation12–Citation14,Citation17

TEH has two main modalities of clinical presentation: as a common single external pile or as a circular thrombosis of external hemorrhoids. This paper is concerned with a single TEH only following Hancock’s definition of “an acute localized thrombosis which may affect the external plexus”.Citation2

TEH occurs accidentally and understandably patients take fright.Citation2,Citation3,Citation17,Citation19 As therapy, physicians inject local anesthesia into anal skin which is very painful, do an incision or excision, and then take thrombi out.Citation2,Citation7,Citation15–Citation17,Citation20,Citation21 Is this necessary? Only a minority of such patients present with formidable swelling, fierce bleeding, and overwhelming pain. Because patients fear surgery, they wait and observe their symptoms. Sometimes they present hours, even days after onset with less swelling, less pain, and no bleeding. Because swelling vanishes, a thrombus must not perforate anal skin, which means no bleeding, and may disappear within two to three weeks by resorption.

There are no randomized controlled trials comparing surgical and conservative management of THE,Citation7,Citation15,Citation16,Citation20 but surgical management is the gold standardCitation10,Citation20,Citation22 if the condition is encountered within the first 72 hours after onsetCitation3,Citation23 or fails to respond to conservative treatment.Citation2,Citation8,Citation18 What happens when a strict conservative management is started with painkillers, a wait-and-see policy, and dry anal cleaning after motionsCitation24,Citation25 independent of stage of TEH at presentation?

Methods

Patients with TEH of both sex, aged 16–80 years, presenting at our office from March 18th, 2004 to August 18th, 2005 referred from general practitioners (GPs), physicians, urologists, or gynecologists because of anal complaints such pain or bleeding, were consecutively enrolled. After proctologic assessment in knee–chest positionCitation26 we informed patients that they had a benign lesion which would not need surgery. It would heal if patients were willing to accept our strict management policy: no water, shower, bath, washcloth, wet wipes, soap, or shower gel, but smooth dry toilet paper for anal cleaning after defecation for one to two weeks, and body cleaning without shower or bath tube but as often as wished with water, soap, or shower gel with an accepted washcloth for their inflamed anal skin to protect it against unknown etiologic factors which might postpone healing.Citation24,Citation25

Questionnaires

Individuals were asked to complete questionnaires with given answers about anal history and symptoms at study entry () and six months later at follow-up ().

Table 1 Patients’ questionnaire with given answers at study entry

Table 2 Patients’ questionnaire with given answers at follow up

Follow-up

Patients were instructed to return to our practice immediately in case of problems. We phoned them six months later to deliver our follow-up questionnaire since we would like to learn how they are and the course of healing of their TEH.

Statistics

We completed intention-to-treat analyses. To compare anal cleaning attitudes at start and six months later, McNemar’s test for related samples was used for significant difference for dichotomous variables and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for ordinal variables. P-values were computed using the exact versions of both tests. The Student’s t-test for independent variables was used to find out which individuals had fewer symptoms: those who followed our strict management policy “more than one week” or “one week or less”. We used SPSS software (v. 15.0.1.1; SPSS inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical guidelines

This study has been conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and was conducted with the understanding and the consent of the patients.

Results

All 72 patients initially accepted our therapeutic regimen. Patient characteristics are summarized in .

Table 3 Patient characteristics at study entry

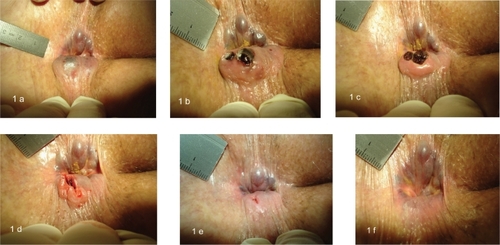

Two patients called on us in the first two weeks after admission because of healing problems: a 32-year-old man was dissatisfied with prolonged healing, but we persuaded him into continuing therapy. A 73-year-old lady was seen repeatedly because of recurrent anal bleeding because of TEH. She was happy with our treatment policy because she escaped surgery ().

Figure 1 All six photos are taken from the same patient. In three-day intervals, they show the healing of a perforated and bleeding single thrombosed external hemorrhoid within nine days of a patient who consequently complied to our strict conservative management policy. A) Day 0: The patient is in knee–chest position, head left. Right-lateral of the anus parts of the uninflamed external hemorrhoidal plexus are protruding. Left-lateral there is edematous tissue with a dark spot (nonperforated thrombosed external hemorrhoid) with a subcutaneous clot. B) Day 3: Perforation and anal bleeding occurred in between. Right-lateral of the anus parts of an unaltered external hemorrhoidal plexus are seen. Left-lateral redness and edema of inflamed anal skin perforated by two black clots. C) Day 6: The right-lateral parts of the external hemorrhoidal plexus remain unchanged. The left-lateral clots are still at same position. D) Day 6: Both clots were taken out. A gaping lesion remains at former perforation site. E) Day 9: A 2–4 mm healing lesion is seen at former perforation site. At right-lateral, unchanged parts of the external hemorrhoidal plexus. F) Day 32: At follow-up four weeks later, the left-lateral perforation can hardly be seen. At right-lateral, the uninflamed subcutaneous external hemorrhoidal plexus appears unchanged.

Median prevalence of TEH per month at our institution was 9 (5–14). A seasonal occurrence was found in springtime. Symptoms at admission were: anal lump (80.3%), pain (73.2%), burning (baking) (43.7%), itching (42.3%), bleeding (28.6%), pricking (26.8%), and/or anal soreness (16.9%). Patients were bothered most by pain (43.5%), lump (40.6%), and anal blood (8.7%). Onset of symptoms was within “some days” in 40.0% of patients, “one week” (34.3%), “four weeks” (12.9%), “half a year” (2.8%), and “one year or longer” (10.0%). Half of patients (50.7%) had not experienced a painful lump earlier, some once (27.5%), others repeatedly (21.7%). 54.9% of patients thought they might have hemorrhoids, 31.0% did not know, and 14.1% declined. 56.4% of patients with assumed hemorrhoids tried to treat themselves. 29.4% had been under medical treatment for so called hemorrhoids when TEH appeared.

At the six-month follow-up (median, range 2–13 months) after admission only 48 out of 72 patients (66.7%) sent their questionnaire back. 62.5% (45/72, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 51.0–74.0) of patients described themselves as “healed” or “ameliorated”, and 4.2% (3/72, 95% CI: 0.0–8.9) as “unchanged”. Asked whether their lesion had healed meanwhile 45.8% (33/72, 95% CI: 34.0–57.6) of patients answered “no”, “undecided”, and “unknown”, and 54.2% (39/72, 95% CI: 42.4–66.0) of patients answered “yes”. Of patients, 61.1% (44/72, 95%CI: 49.6–72.6) argued that our conservative management policy is “valuable to test” or “understandable”, 5.6% (4/72, 95% CI: 0.0–11.0) found it “incomprehensible” or “impracticable”. Of our patients, 33.3% (24/72) did not answer.

Twenty-two (45.8%) out of 48 patients who sent their questionnaire back reported at least one symptom: itching (18.8%), a lump or pricking (both 10.4%), pain (8.3%), sore anus (8.3%), bleeding (6.3%), burning (baking), weeping, mucous (each 4.2%). Symptoms appeared “once a month” (59.1%, 13/22), “once a week” (27.3%, 6/22), and “every day” (13.6%, 3/22). Patients complied with our strict management policy “more than one week” (37.5%, 27/72, 95% CI: 26.0–49.0), “one week” (25.0%, 18/72, 95% CI: 14.8–35.2), and “not at all” or “unknown” (37.5%, 95% CI: 26.0–49.0).

Of our patients, 47.2% (34/72, 95% CI: 35.4–59.0) experienced no recurrences whereas 13.9% (10/72, 95% CI: 5.7–22.1) suspected a recurrence, 4.2% (3/72) of patients did not know, and 34.7% (25/72) of patients did not answer this question. Asked what kind of therapy followed their possible recurrence, patients answered: surgery (two patients), ointments and suppositories (two patients), and 13 patients remembered our anal cleaning policy which was adopted again. Comparing anal cleaning attitudes at start of study and six months later we found no change concerning use of dry toilet paper, wet wipes, shower, soap, or shower gel, besides a decline in use of wetted toilet paper (p = 0.004, exact significance two-tailed, McNemar test). On the contrary, use of shower and bath tube increased considerably (p = 0.01, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Discussion

Our study is small in patient numbers compared to othersCitation8,Citation20,Citation27 but has two advantages: data were gathered prospectively, and follow up period was short for all patients: six months (median, range: 2–13 months) with no range extending up to 4,Citation8 5,Citation20 or 12Citation27 years. Disadvantages are: results were obtained by questionnaire only as with othersCitation20 due to the German insurance system which does not allow to see referred patients for follow-up, and regrettably only two thirds of patients (48/72; 66.7%) sent their follow up questionnaire back. According to the intention-to-treat analysis we calculated these 24 nonresponders as drop-outs.

TEH is common in young personsCitation8,Citation20 which complies with our series mean age being 43 years. Incidence was higher in male than in female patients like with othersCitation8,Citation20 the ratio being 2:1. Similarly to other reports,Citation17,Citation27 half of our patients (50.7%) had a prior history of TEH which might emphasize our suspicion that pruritus ani/perianal anitisCitation1 is the determining precursor of TEHCitation24,Citation25 largely underdiagnosed according to type of proctological assessment.Citation26 At follow-up, the most frequent complain in our series was itching (21.4%). This signifies that anal inflammationCitation1,Citation24,Citation25 is still a problem when TEH has healed.

Patients whose initial presentations were pain or bleeding with or without a lump were more like to be treated surgicallyCitation27 if encountered within the first 72 hours.Citation3,Citation8,Citation23 Since only 40.0% of our patients sought medical help within “some days” after onset of symptoms but the majority (60.0%) later after “one week or more” most of them did not fulfill current prerequisites for surgery.Citation3,Citation8,Citation16,Citation20,Citation23 Most of our patients sought medical help only when THE was healing. Early complications of surgery are postoperative bleeding, urinary retention, painful defecation,Citation15,Citation20 and abscess/fistula.Citation20 Late complications include anal stenosis.Citation16 Even though a possible advantage of surgery might be more rapid symptom resolution, lower incidence of recurrence, and longer remission intervalsCitation27 why should we expose our patients to such risks “since the condition is usually self-limiting and subsides in a few days to a week?”Citation8

Recurrences were found to be less frequent after surgical (6.3%) compared to conservative treatment (25.4%) in a retrospective study.Citation27 One cause might be that patients who had surgery timidly tried to avoid another operation and therefore neglected to present themselves to their surgeon again. The rate of suspected recurrence in our series was high (10/48, 21.3%). Indeed typical complaints distinctive of recurrent TEH were rare: lump (10.4%), pain (8.3%), and bleeding (6.3%). Therefore, recurrences with our patients seem rather unlikely but anal inflammation is supposable announced by itching (18.8%), pricking (10.4%), and a sore anus (8.3%).Citation24,Citation25,Citation28

Patient attitudes against our treatment policy did not influence therapeutic results since the majority of patients characterized it as “valuable to test” or “understandable” (61.1%). These patients had no better results than those who found it “incomprehensible” or “impractical”. After all, two young men had surgery. Both sought advice on the Internet about common treatments of TEH because they were discontent with our strict conservative management policy unlike our tolerating 73-year-old female patient (). Our study indicates that a strict conservative management policy for TEH can be successful since only 5.6% of patients found it “incomprehensible” or “impractical”. Randomized controlled trials with long follow ups are needed, which may ultimately result in current surgical management policies for TEH being abandoned.

Disclosure

The authors disclose no financial or nonfinancial competing interests as well as interpretation of data or presentation of information which may be influenced by personal relationships with other people or organizations. H.R. had the idea. All authors contributed to the design of the study and construction of the study protocol. O.G. was responsible for research. O.G. and H.R. saw the patients and asked them to complete their questionnaires before proctologic assessment and at follow-up. The findings were compiled into a PC study-documentation sheet after medical assessment of each patient. Results were discussed with all authors. Y.H. was responsible for statistical evaluations. O.G. wrote the first drafts which were revised by all authors. H.R. wrote the final draft.

References

- Alexander-WilliamsJPruritus aniBr Med J (Clin Res Ed)1983287159160

- HancockBDABC of colorectal diseases. HaemorrhoidsBMJ1992304104210441586792

- JanickeDMPundtMRSurgical excision of symptomatic thrombosed external hemorrhoids is indicated within 48 to 72 hours of pain onsetEmerg Med Clin N Am199614757758

- NelsonLRTreatment of anal fissureBMJ200332735435512919967

- AbramowitzLSobhaniIBeniflaJLAnal fissure and thrombosed external hemorrhoids before and after deliveryDis Colon Rectum20024565065512004215

- BurkittDPVaricose veins, deep vein thrombosis, and haemorrhoids: epidemiology and suggested aetiologyBr Med J197225565615032782

- GaiFTreccaASuppaMHemorrhoidal thrombosis. A clinical and therapeutic study on 22 consecutive patientsChir Ital20065821922316734171

- OhCAcute thrombosed external hemorrhoidsMt Sinai J Med19895630322784180

- PerrottiPAntropoliCMolinoDConservative treatment of acute thrombosed external hemorrhoids with topical nifedipineDis Colon Rectum20014440540911289288

- EisenstatTSalvatiEPRubinRJThe outpatient management of acute hemorrhoidal diseaseDis Colon Rectum197922315317467196

- ArthurKEAnal haematoma (coagulated venous succule or peri-anal thrombosis)Rev Med Panama19901531342330422

- DelainiGGBortolasiLFalezzaGHemorrhoidal thrombosis and perianal hematoma: diagnosis and treatmentAnn Ital Chir1995667837858712590

- IseliAOffice treatment of hemorrhoids and perianal hematomaAus Fam Physician199120284290

- ThomsonHThe real nature of “perianal haematoma”Lancet198282964674686125640

- NievesPMPerezJSuarezJAHemorrhoidectomy – how I do it: experience with the St.Mark’s Hospital technique for emergency hemorrhoidectomyDis Colon Rectum197720197201300319

- BarriosGKhubchandaniMUrgent hemorrhoidectomy for hemorrhoidal thrombosisDis Colon Rectum197922159161446247

- BrearlySBrearlyRPerianal thrombosisDis Colon Rectum1988314034043366042

- NagleDRolandelliRHPrimary care office management of perianal and anal diseasesPrimary Care1996236096208888347

- MetcalfAAnorectal disordersPostgrad Med19958981947479460

- JongenJBachSStuebingerSHExcision of thrombosed external hemorrhoid after local anesthesia. A retrospective evaluation of 340 patientsDis Colon Rectum2003461226123112972967

- SakulskySBBlumenthalJALynchRHTreatment of thrombosed hemorrhoids by excisionAm J Surg19701205375385507343

- GroszCRA surgical treatment of thrombosed external hemorrhoidsDis Colon Rectum1990332492502311472

- ZuberTJHemorrhoidectomy for thrombosed external hemorrhoidsAm Fam Physician2002651629163211989640

- RohdeHRoutine anal cleansing, so-called hemorrhoids, and perianal dermatitis: cause and effect?Dis Colon Rectum20004356156210789760

- RohdeHSchädigung der Analhaut durch NassreinigungDtsch Med Wschr200513097415812727

- RohdeHDiagnostic errorsLancet2000356127811072979

- GreensponJWilliams StBYoungHAThrombosed external hemorrhoids: outcome after conservative or surgical managementDis Colon Rectum2004471493149815486746

- KuehnH GGebbenslebenOHilgerYRohdeHRelationship between anal symptoms and anal findingsInt J Med Sci20096778419277253