Abstract

Omeprazole is a proton-pump inhibitor indicated for gastroesophageal reflux disease and erosive esophagitis treatment in children. The aim of this review was to evaluate the efficacy of delayed-release oral suspension of omeprazole in childhood esophagitis, in terms of symptom relief, reduction in reflux index and/or intragastric acidity, and endoscopic and/or histological healing. We systematically searched PubMed, Cochrane and EMBASE (1990 to 2009) and identified 59 potentially relevant articles, but only 12 articles were suitable to be included in our analysis. All the studies evaluated symptom relief and reported a median relief rate of 80.4% (range 35%–100%). Five studies reported a significant reduction of the esophageal reflux index within normal limits (<7%) in all children, and 4 studies a significant reduction of intra-gastric acidity. The endoscopic healing rate, reported by 9 studies, was 84% after 8-week treatment and 95% after 12-week treatment, the latter being significantly higher than the histological healing rate (49%). In conclusion, omeprazole given at a dose ranging from 0.3 to 3.5 mg/kg once daily (median 1 mg/kg once daily) for at least 12 weeks is highly effective in childhood esophagitis.

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease and erosive esophagitis in pediatric patients: symptoms and therapeutic approaches

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined as the presence of regurgitation of the gastric contents into the esophagus (gastroesophageal reflux) associated with troublesome symptoms and/or complications.Citation1 Although different abnormalities in motility variables, such as lower esophageal sphincter function, esophageal peristalsis and gastric motor activity can contribute to the development of GERD, the degree of esophageal acid exposure represents the key factor in its physiopathology. GERD is the most common esophageal disorder in childhood and the most frequent reason why infants are referred to the pediatric gastroenterologist, affecting as much as 1.8% to 8.2% of the pediatric population.Citation2 Presenting features of GERD in infants and children are quite variable and follow patterns of gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal manifestations that may vary according to age. Patients may be minimally symptomatic, or may exhibit severe esophagitis, bleeding, failure to thrive, or severe respiratory problems. Symptoms of GERD may include: regurgitation, persistent vomiting, anorexia/feeding refusal, hypersalivation, arching, irritability, persistent crying, abdominal and epigastric pain, heartburn, chest pain, sleep disturbances,Citation3,Citation4 Sandifer’s syndrome (head turning episodes to lengthen the esophagus, repetitive stretching and arching, which gives the appearance of seizure/dystonia),Citation5 dental erosion,Citation6 and many other extra-intestinal manifestations, mainly respiratory symptoms such as stridor, recurrent wheezing, cough, chronic laryngitis, hoarseness, asthma.Citation7–Citation9 In the more severe forms of GERD esophageal complications like erosive or ulcerative esophagitis,Citation10 hemorrhage, stricture, Barrett’s esophagusCitation11,Citation12 may be diagnosed.

The main aims of the treatment of GERD in children are to relieve symptoms, promote normal growth and prevent the afore-mentioned complications. Conservative measures include parent reassurance, positioning and altering feed consistency. Treatment options include decreasing intra-gastric acidity with antacids, histamine H2 receptor blockers and proton pump inhibitors (PPI) and correcting gut motility with prokinetics, such as metoclopramide and domperidone. Surgical approaches like fundoplication are typically reserved to children with severe GERD refractory to medical treatment.

A recent systematic review about the pharmacological management of GERD in childrenCitation13 suggested the only safe and effective medications are ranitidine and omeprazole and probably lansoprazole, being able to promote symptomatic relief, and endoscopic and histological healing of esophagitis. In particular, omeprazole is reported to be effective in children with GERD refractory to ranitidine treatment and should be a first-line treatment in severe esophagitis.Citation13

Omeprazole pharmacology and pharmacokinetics

Omeprazole is a PPI blocking the final common pathway of acid secretion at the luminal surface of the parietal cell by binding to H+K+-ATPase, the so-called “acid pump” or “proton pump” thereby providing potent suppression of gastric acid output. The pro-drug omeprazole is rapidly and almost completely absorbed, with peak plasma levels occurring 1 to 3 hours after ingestion. It is highly (95%) protein-bound and rapidly distributed in plasma. The pro-drug is rapidly metabolized by hepatic cytochrome P-450 isoenzyme CYP2C19, resulting in a very short plasma half-life of 40 to 60 minutes.Citation14 Despite its relatively short plasma half-life, clinically adequate suppression of acid secretion lasts 12 to 15 hours after a single morning dose, because of the covalent binding of omeprazole with the parietal cell proton-pumps exposed toward the gastric lumen. Thus, the anti-secretory effect of omeprazole is not dependent on its plasma concentration at any given time but it is directly proportional to the area under the plasma concentration curve (AUC).Citation14 Omeprazole pharmacokinetic studies in children shows that younger ones tend to have a higher metabolic capacity, resulting in a shorter half life of the drug. This may explain the need for higher doses of omeprazole on a per kilogram basis in children as compared to adults, and even higher in children younger than 6 years of age.Citation15

Omeprazole formulations

Omeprazole is approved for the treatment of GERD and erosive esophagitis in children ≥2 years both by European and US indications.

Omeprazole is commercially available in capsules containing enteric-coated, delayed-release granules that should not be chewed or crushed because of their acid liability. For children who have difficulty in swallowing them, the capsules may be opened and the granules sprinkled on applesauce or yogurt or dispersed in fruit juice or swallowed immediately with water. However, if the child accidentally chews the granules, their bitter taste may result in non-compliance with refusal of subsequent doses.Citation16 In two studiesCitation17,Citation18 omeprazole granules have been dissolved in an alkaline vehicle (8.4% bicarbonate at a concentration of 2 mg/mL) or in milk. The pharmacodynamic resulting from these alternative methods of omeprazole administration has been reported to be the same as for the intact capsule.Citation19 Use of an extemporaneously prepared flavored omeprazole suspension may increase compliance and palatability in pediatric patients. However, the oral bioavailability of omeprazole in non-proprietary formulations has not been accurately assessed yet.

Omeprazole safety and tolerability

The safety and tolerability of omeprazole in both short- and long-term use is demonstrated by the scarcity of adverse effects in spite of extensive use reported in several studies. Most common reported adverse effects have been nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, epigastric pain, skin rash, and irritabilityCitation17,Citation20–Citation22 but generally no severe enough for patient to discontinue the drug. Only one case of anaphylactic reaction due to omeprazole has been reported, in a 14-year-old boy.Citation23 One recent study reported the association of omeprazole and an increased risk of acute gastroenteritis and community-acquired pneumonia in children.Citation24 Hypergastrinemia,Citation22,Citation25–Citation27 parietal cell hyperplasia,Citation28 and occasionally gastric polypsCitation29,Citation30 have also been described in children receiving long-term omeprazole therapy. These changes are usually histologically benign. No statistically significant differences in gastrin level according to omeprazole dosage, dosing frequency or treatment duration has been reported.Citation21 And no correlation between the degree or duration of hypergastrinemia and the presence of polyps or parietal cell changes. A mild elevation in transaminase levels has been reported.Citation25 Therefore, both short- and long-term omeprazole therapy appears to be safe and well tolerated in children despite some biochemical, endoscopic, and histologic changes.Citation20,Citation21

Drug interactions

Omeprazole appears to interact with only one P-450 isoenzyme, CYP2C19.Citation31 Thus it is expected to have a narrow spectrum of interaction limited to drugs metabolized by this enzyme. However, interactions with diazepam, phenytoin, warfarin, digoxin, or methotrexate are reported as not clinically significant.Citation31–Citation36 There is no effect of omeprazole on metabolism of several other drugs tested like theophylline,Citation37,Citation38 propranololCitation39 or cyclosporine.Citation40

Materials and methods

Literature search

We systematically searched PubMed, Cochrane and EMBASE (1990 to 2009) to identify studies evaluating the efficacy of delayed release oral suspension of omeprazole for the treatment of erosive esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux in children. The search terms used included: “omeprazole”, “gastroesophageal (or gastro-oesophageal) reflux”, “erosive esophagitis (or oesophagitis)”, “child$” (or “infant$”) and “drug$” or “therapy” or “treatment”. These terms were combined in various ways to generate a wide search. In addition, we checked references of eligible articles for further papers that were not captured by our search strategy and corresponded with authors when a full-length article was not available directly on-line or when relevant information was missing in the paper.

Inclusion criteria

We included articles that met the following pre-determined criteria: a) clinical trials performed in pediatric patients reporting on efficacy of omeprazole for the treatment of erosive esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux in children, b) only delayed release omeprazole as oral suspension: ie, powder for oral suspension (Prilosec) or capsule content in liquid vehicle or non-encapsulated intact enteric-coated granules administered with fluids, c) studies in English language, d) studies with adequate data about number and age of treated children, endoscopic diagnosis, total daily dose and duration of treatment.

Data extraction and synthesis

A form was generated to register whether individual studies met eligibility criteria and collect data regarding study design and methodological quality. Two investigators independently reviewed and extracted data from the papers according to the pre-determined criteria. Any differences in opinion about the studies were resolved by discussion between them.

Outcomes

Our analysis focused on the following measures of therapeutic efficacy: GERD symptom relief/resolution, reduction in reflux index, endoscopic and/or histological healing of esophagitis.

Analysis

Selection bias and lack of common outcome measures were some of the problems preventing a proper metanalysis. Therefore, we defined subgroups for the analysis by dividing studies into 3 groups according to the outcome measures considered in each paper: a) GERD symptom relief/resolution, b) reduction in reflux scores as documented by 24-hour esophageal and/or gastric pH-monitoring, and c) endoscopic and/or histological healing of esophagitis.

Results

Our literature search identified 59 potentially relevant articles. After reviewing the titles and abstracts and the full-length articles, 12 articles were selected for closer assessment and then included in our analysis.Citation17,Citation18,Citation22,Citation25–Citation27,Citation41–Citation46 They are summarized in .

Table 1 Clinical trials testing delayed-release omeprazole in children

Of the 12 selected studies, 10 were controlled trials, 2 were randomized controlled trials (1 was placebo-controlledCitation41 and the other compared omeprazole to ranitidineCitation27). Ten were single-center studies, 2 were multi-center studies (1 of them was multinationalCitation42). Overall, data from a total of 262 children were reported. Children’s age showed a wide range of variability ranging from 1.25 months to 18 years. The treatment duration varied widely, ranging from 2 to 24 weeks, but after 2 weeks only intra-esophageal and/or gastric pH was evaluated in 2 studiesCitation17,Citation41 and in 1 study also endoscopy was performed as early as within 2 weeks.Citation22 The median dose of omeprazole was 1 mg/kg once daily (range 0.26–3.5 mg/kg). In all studies omeprazole was administered as a capsule or as the capsule content dispersed in a weakly acid vehicle, except for 2 studiesCitation17,Citation18 where granules were dispersed in non-acid vehicles.

In general all the studies had similar aims, but some had different approaches, and consequently slightly different results. In the study by Cucchiara et alCitation27 omeprazole decreased clinical score by 83%, improved histological and endoscopic degree of esophagitis by 75% and 82%, respectively, and reduced esophageal acid exposure by 61.9% and intra-gastric acidity by 29%. Moore et alCitation41 reported significant reduction in reflux index without a significant reduction in irritability, which was the only evaluated symptom. In the study by Hassal et alCitation42 omeprazole healed endoscopic esophagitis in 95% of children and improved reflux symptoms in 91.5% even in the unhealed children. Alliet et alCitation18 reported symptom improvement in 67%, endoscopic healing in 100% and histological healing in 67% of children and a significant reduction of intra-gastric acidity. Bishop et alCitation17 reported a significant improvement both in reflux index and intra-gastric acidity and a significant improvement in clinical score in children younger than 2 years. In another study Cucchiara et alCitation43 reported symptom resolution or improvement in all patients and improvement in the endoscopic degree of esophagitis in 76% of cases. Kato et alCitation22 reported symptom improvement in all children, endoscopic healing of esophagitis in 80% of children and significant reduction of intra-gastric acidity. De Giacomo et alCitation44 showed endoscopic, but not histological, healing of esophagitis in 90% of treated children, symptoms improvement in 100% and a significant reduction in reflux index. Karjoo et alCitation45 reported symptom improvement in 87% of treated children. Gunasekaran et alCitation25 reported symptom resolution, esophageal acid exposure within normal range and endoscopic healing of esophagitis in 100% of children by 6 months of treatment. Boccia et alCitation46 reported endoscopic healing of esophagitis in 96% of children and symptom resolution in 35%. Strauss et alCitation26 showed symptom resolution or improvement in 100%, histological healing of esophagitis in 37.5% and endoscopic healing in 100% of children.

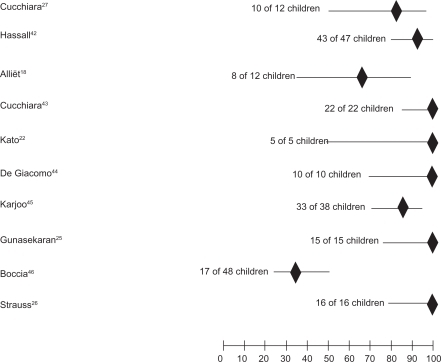

For the purpose of our analysis, the studies were divided in subgroups according to the outcome parameters measured. shows esophageal and gastric pH-monitoring, shows endoscopic and histological results, and shows percentage of asymptomatic children after treatment.

Figure 1 Symptom resolution rates in the 10 studies reporting percentage of asymptomatic children after treatment.

Table 2 Studies evaluating esophageal and/or gastric pH-monitoring

Table 3 Studies evaluating rates of endoscopic and/or histological healing of esophagitis

All studies evaluated symptom relief/resolution, even if the symptoms considered and the scores used to graduate their presence/intensity were not homogeneous. GERD symptom improvement or disappearance were reported as percentage of asymptomatic children in 10 studiesCitation18,Citation22,Citation25–Citation27,Citation42–Citation46 and showed symptomatic response in 189 out of 235 treated children (80.4%) but rate of symptom relief widely varied ranging from 35% to 100% (). In 2 studiesCitation17,Citation41 the clinical score only was reported, and was significantly decreased in 1 study.Citation17

Five studiesCitation17,Citation25,Citation27,Citation41,Citation44 evaluated reduction of esophageal reflux index, 4 studiesCitation17,Citation18,Citation22,Citation27 measured reduction of intra-gastric acidity (2 of them monitored both the esophageal and the gastric pH). Out of these 5 studies analyzing the esophageal 24-hour pH profile, 4 were comparable since they reported homogeneous data, ie, the median percentage of time of esophageal pH < 4 (reflux index) before and after omeprazole treatment. In all studies reflux index was significantly decreased and was always within normal limits (ie, <7%) ranging from 1% to 5.4%. Out of the 4 studies measuring reduction of intra-gastric acidity, 3 were comparable since they homogeneously reported the median percentage of time of gastric pH < 4 both before and after treatment. Percentage of time of gastric pH < 4 significantly decreased from 20% to 69%.

Nine studies evaluated the rate of healing of esophagitis in term of endoscopic healingCitation18,Citation22,Citation25–Citation27,Citation42–Citation44,Citation46 and in 4 of them histological healing was also evaluated.Citation18,Citation26,Citation27,Citation44 For the purpose of our analysis, we considered as endoscopically healed a macroscopically normal esophageal mucosa, corresponding to grades 0 and 1 of Hetzel and Dent scale.Citation47 According to this criterion, patients presenting a grade 1 esophagitis at baseline were excluded from the calculation for the healing rate. The majority of children where endoscopic healing was reported were treated for 12 weeks or longer and healing tended to be better than in children treated for 8 weeks or less (P = 0.053). Histological healing was defined according to different criteria, so results were non comparable and we analyzed only the percentage of children reported as histologically healed. Overall the histological healing rate was significantly lower than the endoscopic healing in these 4 studies (49% vs 91%, P = 0.0001).

Discussion

In this review evidences about the efficacy of omeprazole treatment for esophagitis in children have been systematically reviewed. Efficacy has been evaluated in terms of symptom relief, normalization or improvement of gastric and/or esophageal acidity, and endoscopic and/or histological healing of esophagitis.

In 10 of 12 studies omeprazole was very effective in improving or resolving GERD symptoms, both when evaluated as a percentage of asymptomatic children or as a decreased symptom score. However, in 2 studies efficacy on symptoms was lower, particularly on irritability. Moore et alCitation41 reported that omeprazole did not significantly reduce irritability score in infants. However, irritability being evaluated by subjective methods, such as a diary of crying and fussing time and a visual analogue score of parental impression of its intensity was the only symptom evaluated. And when efficacy on reducing esophageal pH was assessed even in these infants a significant reduction in reflux index was seen. Similarly Boccia et alCitation46 reported a low symptom resolution rate of 35%. However, analyzing each reported symptom even in this study irritability was the only non-improving one, whereas frequency of other symptoms like vomiting, heartburn, epigastric pain, and dysphagia significantly decreased. Therefore, the failure of omeprazole in treating irritability, despite effective acid suppression and significant efficacy on other symptom improvement, may be explained by the hypothesis that some infants/children could be irritable because of non-acid reflux or irritability could be a self-limiting condition tending to improve only over time.

The efficacy of omeprazole in suppressing acid output has been demonstrated by esophagealCitation17,Citation25,Citation27,Citation41,Citation44 and/or gastricCitation17,Citation18,Citation22,Citation27 pH monitoring or both.Citation17,Citation27 In particular, all the studies analyzing esophageal pH-monitoring showed an effective acid suppression by omeprazole, reducing the percentage of time of esophageal pH < 4 to less than 6%, a reflux index >7% being considered abnormal according to recent guidelines of North American and European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology.Citation48

Omeprazole resulted to be very effective in healing esophagitis in children. Although data are analyzed in different way from studies performed in adults, and so results are not completely comparable, efficacy in children seems to be better than in adults. Indeed, a recent systematic reviewCitation49 reported the overall endoscopic healing for omeprazole in adults of 73.8% (95% CI 71–76) and in our children treated for 8 weeks or less was similar (84%, 95% CI 71–93) but in those treated for 12 weeks or longer healing rate was significantly higher (95%, 95% CI 89–98). The possible better efficacy of omeprazole in children might be due to the higher dosage used in children, in whom doses of omeprazole are given on a per kilogram basis; or, alternatively, to a lesser severity of the inflammatory changes due to a shorter duration of the reflux disease in the younger population. However, when analyzed, the histological healing even in children was significantly lower, and in 2 studiesCitation26,Citation44 histological parameters did not correlate with endoscopic healing or symptomatic relief.

Comparing omeprazole with other most common drugs or surgical approaches used for GERD and esophagitis treatment in children, omeprazole seem to be more effective. Most of the children successfully treated with omeprazole included in this review were unresponsive to previous medical treatments with anti-acids, H2-receptor blockers, pro-kinetic agents or surgery. However, when looking more carefully at the data presented the higher efficacy of omeprazole compared to ranitidine is not proven. Karjoo et alCitation45 initially treated children with 8 mg/kg once daily ranitidine, increasing to 12 mg/kg once daily if no symptomatic improvement was observed after 2 weeks, but this apparent failure of ranitidine could be due to a too short period of observation or, more probably, to a too low dosage of ranitidine. Indeed, when Cucchiara et alCitation27 directly compared omeprazole 1 mg/kg once daily to ranitidine at the dose of 20 mg/kg once daily efficacy was similar in symptom relief, endoscopic and histological healing, and in reducing esophageal and gastric acidity, whereas the same children previously treated with ranitidine at the dosage of 8 mg/kg once daily had not responded. Dosage of ranitidine is known to correlate with the esophageal reflux index and a dose lower than 10 mg/kg dail is indeed ineffective to heal esophagitis.Citation50 However, data on the similarity of ranitidine and omeprazole efficacy in the treatment of childhood esophagitis are insufficient and other head-to-head studies are necessary, particularly because in adults omeprazole was reported to have a superior efficacy to H2-receptor blockers in treating esophagitis.Citation51

Similarly, data on usefulness of maintenance therapy or in-demand therapy for prevention of recurrence in children are insufficient. Only in 1 studyCitation46 were children followed after healing and maintenance therapy for longer enough to assess prevalence of relapse and found symptoms recurrence only in 6.8% of children even after maintenance discontinuation, unsupporting the necessity of maintenance therapy.

Conclusion

In conclusion, delayed-release oral suspension of omeprazole given at a median dosage of 1 mg/kg once daily for a median duration of 12 weeks showed high efficacy in treating GERD and esophagitis in children. Moreover, thanks to its safety and tolerability omeprazole use in childhood can be extended to clinical settings. The need for a long-term maintenance therapy, however, is still to be assessed in the pediatric population.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ShermanPMHassallEFagundes-NetoUA global, evidence-based consensus on the definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the pediatric populationAm J Gastroenterol20091041278129519352345

- NelsonSPChenEHSyniarGMChristoffelKKPrevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during childhood: a pediatric practice-based survey. Pediatric Practice Research GroupArch Pediatr Adolesc Med200015415015410665601

- VandenplasYHauserBGastro-oesophageal reflux, sleep pattern, apparent life threatening event and sudden infant death. The point of view of a gastro-enterologistEur J Pediatr200015972672911039125

- GhaemMArmstrongKLTrockiOCleghornGJPatrickMKShepherdRWThe sleep patterns of infants and young children with gastro-oesophageal refluxJ Paediatr Child Health1998341601639588641

- CerimagicDIvkicGBilicENeuroanatomical basis of Sandifer’s syndrome: a new vagal reflex?Med Hypotheses20087095796118031943

- DahshanAPatelHDelaneyJWuerthAThomasRToliaVGastroesophageal reflux disease and dental erosion in childrenJ Pediatr200214047447812006966

- DebleyJSCarterERReddingGJPrevalence and impact of gastroesophageal reflux in adolescents with asthma: a population-based studyPediatr Pulmonol20064147548116547933

- StørdalKJohannesdottirGBBentsenBSCarlsenKCSandvikLAsthma and overweight are associated with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal refluxActa Paediatr2006951197120116982489

- BlockBBBrodskyLHoarseness in children: the role of laryngopharyngeal refluxInt J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol2007711361136917644193

- El-SeragHBBaileyNRGilgerMRabenekLEndoscopic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients between 18 months and 25 years without neurological deficitsAm J Gastroenterol2002971635163912135011

- HassallEEndoscopy in children with GERD: “the way we were” and the way we should beAm J Gastroenterol2002971583158612135003

- SharmaPMcQuaidKDentJA critical review of the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus: the AGA Chicago WorkshopGastroenterology200412731033015236196

- TigheMPAfzalNABevanABeattieRMCurrent pharmacological management of gastro-esophageal reflux in children: an evidence-based systematic reviewPaediatr Drugs20091118520219445547

- IsraelDMHassallEOmeprazole and other proton pump inhibitors: pharmacology, efficacy, and safety, with special reference to use in childrenJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr1998275685799822325

- AnderssonTHassallELundborgPPharmacokinetics of orally administered omeprazole in children. International Pediatric Omeprazole Pharmacokinetic GroupAm J Gastroenterol2000953101310611095324

- ZimmermannAEWaltersJKKatonaBGSouneyPELevineDA review of omeprazole use in the treatment of acid-related disorders in childrenClin Ther20012366067911394727

- BishopJFurmanMThomsonMOmeprazole for gastroesophageal reflux disease in the first 2 years of life: a dose-finding study with dual-channel pH monitoringJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200745505517592364

- AlliëtPRaesMBruneelEGillisPOmeprazole in infants with cimetidine-resistant peptic esophagitisJ Pediatr19981323523549506656

- ZimmermannAEWaltersJKKatonaBSouneyPAlternative methods of proton pump inhibitor administrationConsult Pharm199712990998

- HassallEKerrWEl-SeragHBCharacteristics of children receiving proton pump inhibitors continuously for up to 11 years durationJ Pediatr200715026226717307542

- ToliaVBoyerKLong-term proton pump inhibitor use in children: a retrospective review of safetyDig Dis Sci20085338539317676398

- KatoSEbinaKFujiiKChibaHNakagawaHEffect of omeprazole in the treatment of refractory acid-related diseases in childhood: endoscopic healing and twenty-four-hour intragastric acidityJ Pediatr19961284154218774516

- TaymanCMeteECatalFTonbulAHypersensitivity reaction to omeprazole in a childJ Investig Allergol Clin Immunol20091917677

- CananiRBCirilloPRoggeroPWorking Group on Intestinal Infections of the Italian Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (SIGENP). Therapy with gastric acidity inhibitors increases the risk of acute gastroenteritis and community-acquired pneumonia in childrenPediatrics2006117e817e82016651285

- GunasekaranTSHassallEGEfficacy and safety of omeprazole for severe gastroesophageal reflux in childrenJ Pediatr19931231481548320610

- StraussRSCalendaKADayalYMobassalehMHistological esophagitis: clinical and histological response to omeprazole in childrenDig Dis Sci1999441341399952234

- CucchiaraSMinellaRIervolinoCOmeprazole and high dose ranitidine in the treatment of refractory reflux oesophagitisArch Dis Child1993696556598285777

- HassallEDimmickJEIsraelDMParietal cell hyperplasia in children receiving omeprazole (abstract)Gastroenterology1995108A121

- IsraelDMDimmickJEHassallEGastric polyps in children on omeprazole (abstract)Gastroenterology1995108A110

- PashankarDSIsraelDMGastric polyps and nodules in children receiving long-term omeprazole therapyJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr20023565866212454582

- OosterhuisBJonkmanJHGOmeprazole: Pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and interactionsDigestion198944Suppl 19172691315

- AnderssonTAndrenKCederbergCEdvardssonGHeggelundALundborgPEffect of omeprazole and cimetidine on plasma diazepam levelsEur J Clin Pharmacol19903951542276389

- GuglerRJensenJCOmeprazole inhibits oxidative drug metabolism. Studies with diazepam and phenytoin in vivo and 7-ethoxycoumarin in vitroGastroenterology198589123512413932118

- SutfinTBalmerKGaströmHErikssonSHöglundPPaulsenOStereoselective interaction of omeprazole with warfarin in healthy menTher Drug Monit1989111761842718223

- CohenAFKroonRSchoemakerHXHoogkamerHvan VlietAInfluence of gastric acidity on the bioavailability of digoxinAnn Intern Med19911155405551883123

- RedTYemACadillacMCarlsonRWImpact of omeprazole on the plasma clearance of methotrexateCancer Chem Pharmacol1993338284

- GuglerRJensenJCDrugs other than H2-receptor antagonists as clinically important inhibitors of drug metabolism in vivoPharmacol Ther1987331331372888140

- TaburetAMGeneveJBocquentinMSimoneauGCaulinCSinglasETheophylline steady state pharmacokinetics is not altered by omeprazoleEur J Clin Pharm199242343345

- HenryDBrentPWhyteIMihalyGDevenish-MearesSPropranolol steady-state pharmacokinetics are unaltered by omeprazoleEur J Clin Pharmacol1987333693733443142

- BlohmeIAnderssonTIdströmJPNo interaction between omeprazole and cyclosporineBr J Clin Pharmacol199335155160

- MooreDJTaoBSLinesDRHirteCHeddleMLDavidsonGPDouble-blind placebo-controlled trial of omeprazole in irritable infants with gastroesophageal refluxJ Pediatr200314321922312970637

- HassallEIsraelDShepherdROmeprazole for treatment of chronic erosive esophagitis in children: a multicenter study of efficacy, safety, tolerability and dose requirements. International Pediatric Omeprazole Study GroupJ Pediatr200013780080711113836

- CucchiaraSMinellaRCampanozziAEffects of omeprazole on mechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux in childhoodDig Dis Sci1997422932999052509

- De GiacomoCBawaPFranceschiMLuinettiOFioccaROmeprazole for severe reflux esophagitis in childrenJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr1997245285329161946

- KarjooMKaneROmeprazole treatment of children with peptic esophagitis refractory to ranitidine therapyArch Pediatr Adolesc Med19951492672717858685

- BocciaGMangusoFMieleEBuonavolontàRStaianoAMaintenance therapy for erosive esophagitis in children after healing by omeprazole: is it advisable?Am J Gastroenterol20071021291129717319927

- HetzelDJDentJReedWDHealing and relapse of severe peptic esophagitis after treatment with omeprazoleGastroenterology1988959039123044912

- VandenplasYRudolphCDDi LorenzoCPediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and NutritionJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr20094949854719745761

- EdwardsSJLindTLundellLDASRSystematic review: standard- and double-dose proton pump inhibitors for the healing of severe erosive oesophagitis – a mixed treatment comparison of randomized controlled trialsAliment Pharmacol Ther20093054755619558609

- SalvatoreSHauserBSalvatoniAVandenplasYOral ranitidine and duration of gastric pH > 4.0 in infants with persisting reflux symptomsActa Paediatr20069517618116449023

- KhanMSantanaJDonnellanCPrestonCMoayyediPMedical treatments in the short term management of reflux oesophagitisCochrane Database Syst Rev20074182CD00324417443524